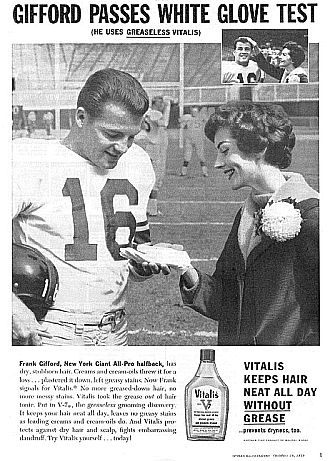

This Vitalis hair tonic ad featuring Frank Gifford ran in “Sports Illustrated,” October 1959 – and likely others as well.

Frank Gifford, a talented football player for the New York Giants in the 1950s and 1960s, became a popular figure in the New York city metro area and nationally both during and after his active playing career.

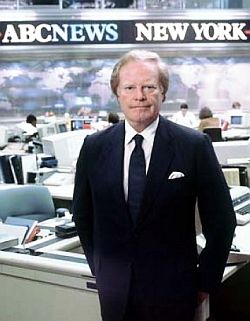

Gifford not only became a familiar face in magazine and TV advertising, but also one of the first professional athletes to successfully venture into TV sports broadcasting.

Well beyond his playing days, Frank Gifford would extend his celebrity for many years as a sports announcer, first for CBS on radio and TV, and later for ABC-TV’s popular Monday Night Football program.

Gifford’s notice as a public figure, in fact, would span nearly six decades, during which he became a pitchman for dozens of products – from shaving cream and hair tonic to clothing lines, as well as a celebrity draw for CBS Radio and ABC-TV.

Frank Gifford, No. 16, in action as New York Giants battle St. Louis Cardinals, 1960. Photo, George Silk/Life.

All-American

An All-American college player at the University of Southern California (USC), Gifford was drafted by the New York Giants in 1952 and excelled there for 12 seasons. He became an All-Pro performer and a popular sports icon. In the hair tonic ad above, Gifford is shown in his Giants attire being subject to “the white glove test” for the “greasless Vitalis.” The hair tonic, produced by Bristol-Meyers from the 1940s, became popular in that era, and advertising using celebrities helped boost sales. Says the ad’s copy:

“…Frank Gifford, New York Giants, All Pro halfback, has dry, stubborn hair. Creams and cream-oils threw it for a loss… plastered it down, left greasy stains. Now Frank signals for Vitalis. No more grease-down hair, no more messy stains. Vitalis took the grease out of hair tonic. Put in V-7, the greasless grooming discovery. It keeps your hair neat all day, leaves no greasy stains as leading creams and cream-oils do. And Vitalis protects against dry hair and scalp, fights embarrassing dandruff… Try Vitalis yourself….today!

1996: Sportscaster celebrities Al Michaels, Frank Gifford, and Bob Costas appear in “milk mustache” ad campaign.

Even in his college days as a gridiron standout at the USC, Frank Gifford received national notice in general-circulation and sports magazines, including Life magazine which featured a photo sequence of one of Gifford’s touchdown runs against the University of California in a famous November 1951 game.

Magazine and newspaper coverage during his college and pro careers helped keep Frank Gifford in the public eye. And owing to his good looks and landing in the New York media market, Gifford would have continuing good fortune, not only in advertising, but also in TV and film. In his earlier years, as a student in California, Gifford landed some bit parts in Hollywood films, including appearances as a football player in That’s My Boy in 1951 and The All American, with Tony Curtis, released in 1953. He also appeared in Sally and St. Anne and Bonzo Goes to College, both in 1952, the latter a sequel to the Ronald Reagan film, Bedtime for Bonzo.

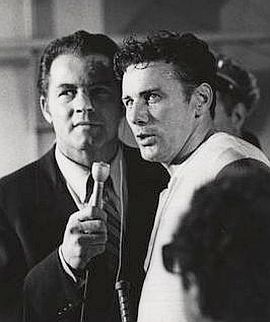

Dec. 1956: Frank Gifford with TV show host, John Daily, taking questions from celebrity panel trying to guess Gifford’s line of work on quiz show,“What’s My Line?”

After a few rounds of questions, and some excitement over Gifford’s youthful good looks by actress panelist Arlene Francis, the panel figured out he was Frank Gifford, football star of the New York Giants, who earlier that day in fact, had a banner performance with four touchdowns in a game against the Washington Redskins.

1950s: New York Giants star halfback, Frank Gifford, being interviewed in mock locker-room halftime scene in TV ad endorsing Florida orange juice.

An announcer with microphone then appears, and begins interviewing Gifford, commending him on his first half play, then launching into the virtues of Florida orange juice, with Frank making a few comments before the scene cuts to the announcer making a final appeal for Florida orange juice.

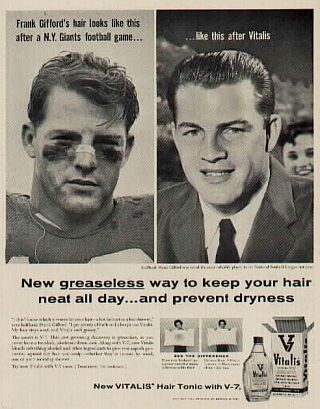

An earlier Vitalis hair tonic ad from 1957 featured Gifford in “before and after” photos, as shown below.

Frank Gifford in a Vitalis Hair tonic ad that appeared in Life magazine, November 25, 1957.

“Frank Gifford’s hair looks like this after a New York Giants football game…” — says ad’s copy on the first photo, showing Gifford in his game face and roughed-up playing attire, hair tousled. Then comes the “after” photo showing a cleaned-up, well-groomed Gifford in coat and tie, as the caption adds – “…like this after Vitalis.” A headline running across the page beneath both photos continues the Vitalis pitch: “New greaseless way to keep your hair neat all day…and prevent dryness.”

The ad’s copy also quotes Gifford pitching the product as follows: “I don’t know which is worse for your hair – a hot helmut or a hot shower,” says halfback Frank Gifford. “I get plenty of both so I always use Vitalis. My hair stays neat, and Vitalis isn’t greasy.” Then the ad copy continues:

“The secret is V-7. This new grooming discovery is greaseless, so you never have a too-slick, plastered-down look. Along with V-7, new Vitalis blends refreshing alcohol and other ingredients to give you superb protection against dry hair and scalp – whether they’re caused by wind, sun or you morning shower. Try new Vitalis with V-7 soon (Tomorrow, for instance.).” Then for the housewife contingent, two smaller photos show a lady holding a pillow, one soiled, the other clean, with appropriate captions: “Does your husband use a greasy tonic that stains pillowcases like this? Greaseless Vitalis leaves pillow cases clean – like this.”

1958: Gifford sweater ad. |

1965: Jantzen swimwear ad. |

1960s: Gifford, beach wear. |

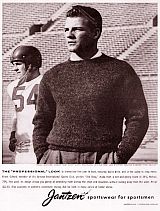

1962: Jantzen sweater ad. |

As Jantzen Model

Gifford also became a model for the Jantzen brand of clothing during the 1950s and 1960s. Jantzen, a company founded in Portland, Oregon from a small knitting business in the 1910s, grew to become a world wide operation by the 1930s, known mostly for women’s swimwear, but by the 1950s, had also established a mens’ line of clothing. From 1957 through the late 1960s – during his playing years and after – Frank Gifford appeared in dozens of clothing, sportswear, and swim wear ads for the Jantzen brand. In the early round of these ads, Gifford appeared by himself, usually donning sweaters. In other Jantzen ads, Gifford appeared with one or more fellow professional athletes, including: Bobby Hull, ice hockey player; Jerry West, basketball star; football competitor, Paul Hornung of the Green Bay Packers; and others. In the 1965 Jantzen swim wear ad, above right, Gifford appears in a beach scene with a surf board and three others – John Severson, a surfer and then publisher of Surfer magazine; Boston Celtics basketball star, Bob Cousy; and Terry Baker, then a famous former quarterback and Heisman Trophy winner from Oregon State University. Other Jantzen swimwear and/or beachwear ads in this period also included Gifford with one or more other athletes, as seen in the 3rd photo here bottom left, with Gifford in the foreground and the others in the background. In the 1962 Jantzen sweater ad at bottom right, Gifford is seated reading a mock headline about his running back rival, Paul Hornung (who won the MVP award in 1961), while Bob Cousy and pro golfer Ken Venturi stand behind him.

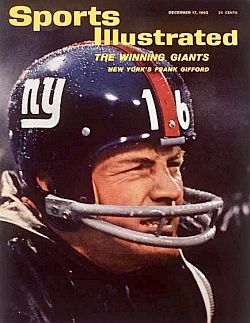

September 1962: Frank Gifford, NY Giants, featured on the cover of Sports Illustrated. Click for copy.

Football Star

Being a football star, Gifford remained in the public eye as newspaper and magazine stories were written about his play. In September 1962, as the New York Giants were having one of their best seasons with Gifford’s help, he appeared on the cover of Sports Illustrated. During his 12 seasons with the New York Giants, Gifford as a running back had 3,609 rushing yards and 34 touchdowns in 840 carries. As a receiver he had 367 catches for 5,434 yards and 43 touchdowns. And finally, throwing the ball, Gifford completed 29 of the 63 passes for 823 yards and 14 touchdowns, the most among any non-quarterback in NFL history.

Gifford made eight Pro Bowl appearances during his career and also played in five NFL Championship games. His biggest season may have been 1956, when he won the Most Valuable Player award of the NFL, and led the Giants to the NFL title over the Chicago Bears. Gifford also played in the famous December 1958 championship game between the New York Giants and the Baltimore Colts – a nationally-televised game that went into sudden death overtime, a game which many believe ushered in the modern era of big-time, television-hyped, pro football.

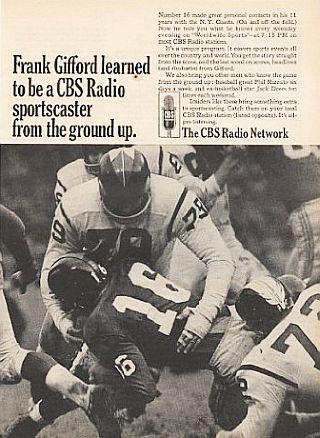

1966: Frank Gifford featured in CBS Radio ad.

CBS Career

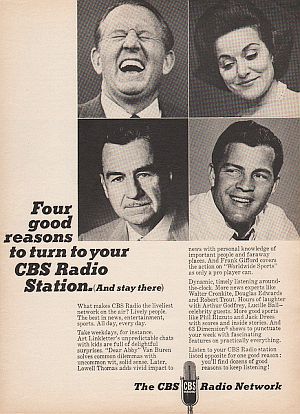

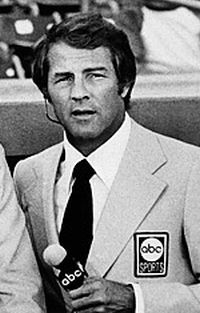

After his playing days ended, Gifford became a full-time broadcast commentator for NFL games, first on CBS radio and later, CBS television. Gifford’s broadcasting career had actually started in 1957 while he was still playing halfback for the New York Giants. He was a commentator for CBS on the NFL pre-game show and joined the CBS staff in 1961 as a part-time sports reporter.

In 1964, Gifford retired from his successful football career with the Giants and remained well-known and well-regarded in the New York area and nationally.

In 1965, CBS hired him full time to cover pro football, college basketball and golf. Gifford stayed with CBS for six years – and as the CBS Radio ad at left shows, the network wasn’t shy about using his football celebrity to lure listeners and sponsors.

Another CBS Radio ad that ran in the 1960s had Gifford featured with three other CBS Radio personalities – Art Linkletter, Amy Van Buren of “Dear Abby” fame, and commentator Lowell Thomas – “Four Good Reasons to Turn to Your CBS Radio Station,” as the CBS ad put it.

Film & TV

Frank Gifford, foreground, as Ensign Cy Mount, here injured, in 1959 James Garner film “Up Periscope.” Click for DVD.

Gifford had a named role in another James Garner film, Up Periscope in 1959, a WWII submarine drama in which Gifford played Ensign Cy Mount, and is shown in one scene (at right) propped up on a stretcher, shirtless and wounded. In television, Gifford appeared in the Shirley Booth sitcom Hazel for a 1963 episode titled, “Hazel and the Halfback.”

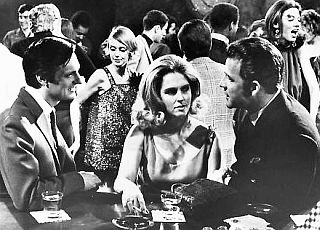

1968: Alan Alda, left, visits with Maxine and Frank Gifford, right, in a scene from the film, “Paper Lion.” Click for DVD.

In 1964, Gifford made a second appearance on the TV quiz show, What’s My Line?, this time as a celebrity panelist asking the questions. In 1965, Gifford was approached to play the lead role in a Tarzan film, but that role later went to Mike Henry.

In 1968, he and his then-wife Maxine appeared in the film, Paper Lion, based on the 1966 nonfiction book by American writer George Plimpton, who spends time as a player with the Detroit Lions to do an insider’s account of how an average American male might fare in professional football.

In the film Alan Alda played Plimpton and Gifford and his wife appeared as themselves in one scene as shown at left.

As a CBS sportscaster, Frank Gifford landed some notable interviews, here with Mickey Mantle in 1966.

Gifford, reportedly, did not think much of Mantle, though he did figure into a bit of early Mickey Mantle baseball lore. That story involves a long home run Mantle hit as a Yankee rookie when he was 19 years old – a home run rumored to have traveled 550 feet or so.

In a May 1951 spring training game played at the University of Southern California, Mantle hit two home runs – one of which cleared the fences there and kept on going, landing in the middle of an adjacent football field, according to Gifford, who was then in spring football training with his college team on that field.

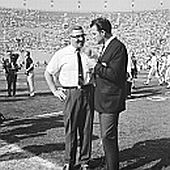

Gifford & Vince Lombardi, pre-Superbowl I, January 1967.

As a former New York Giants running back, Gifford had played under Lombardi when Lombardi was the Giants’ offensive coordinator under head coach Jim Lee Howell, helping lead the Giants to their 1956 championship.

Howell was from an earlier football era and used the single-wing formation. Lombardi helped modernize the Giants’ attack by introducing the T-formation.

1970: Frank Gifford interviewing Kansas City quarterback Len Dawson following Superbowl IV.

At the game’s conclusion, CBS announcer Gifford got the go ahead to go into the losing Cowboys’ locker room for on-air post-game interview – a practice unheard of in that era. Gifford sought out Dallas quarterback Don Meredith, who Gifford knew, for his thoughts on the game. The Meredith interview, emotional but thoughtful, received considerable attention, and would later become a factor in Meredith’s own broadcasting career.

In the photo at right, Gifford is shown interviewing quarterback Len Dawson of the Kansas City Chiefs following Superbowl IV.

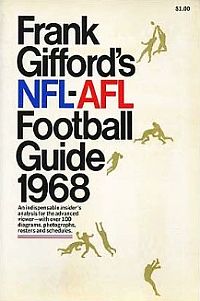

A Frank Gifford pro football guide book.

By the late 1960s, Gifford’s name also began appearing on annual football guide books – Frank Gifford’s NFL-AFL Football Guide For 1968 (shown at left), and a similar volume for 1969, were published by Signet Books. The guides featured rosters, schedules, and forecasts for the upcoming pro seasons, with team summaries, description of the playoff system, and other football information.

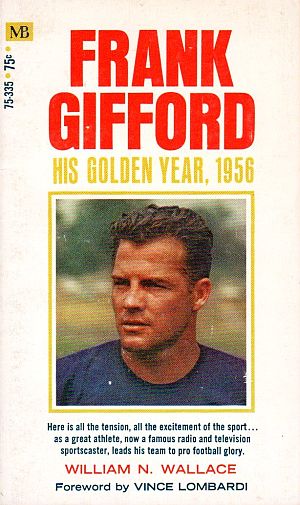

Also in 1969, there was a book about Gifford written by William Wallace – Frank Gifford: His Golden Year, 1956 – the year Gifford won the most valuable player award, then known as the Jim Thorpe Memorial Trophy. The Wallace book included an introduction by Gifford’s former Giants’ coach and then famous Green Bay Packer leader, Vince Lombardi.

The book came at a time when Gifford – then retired from the game since 1962 – was building a following as “one of the better sportscasters on WCBS-TV,” as Kirkus Reviews described Gifford in a short summary of the Wallace book (see “Sources” section at end of story for cover photo of this book).

_____________________________________

“Gifford’s Gigs”

Ads, Film, TV, Books, Etc.

1950s-2000s

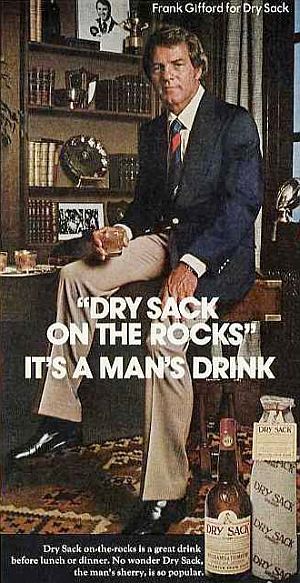

1970s: Frank Gifford appearing in a Dry Sack sherry ad.

Screenshot from a Planters Nuts TV ad featuring Frank Gifford.

Monday Night Football

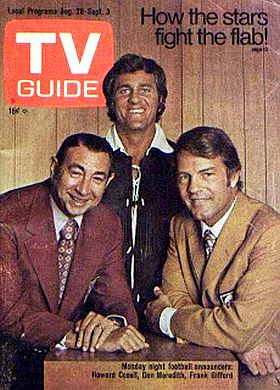

Frank Gifford, right, joined “Monday Nigh Football” broad-casters Howard Cosell, center, and Don Meredith in 1971.

The idea for televising professional football games on Monday night had first started with NFL commissioner Pete Rozelle. Rozelle had experimented with one non-televised Monday night game in September 1964 when the Green Bay Packers played the Detroit Lions in a game that drew a sellout crowd of 59,203 to Tiger Stadium, the largest crowd ever to watch a professional football game in Detroit up to that point. Rozelle then followed up with a few televised Monday night games in prime time over the next four years – two NFL games on CBS for the 1966 and 1967 seasons, followed by two AFL Monday night games on NBC in 1968 and 1969. But neither CBS or NBC would sign a contract for a full season of televised Monday night games, as they feared a disruption of existing programming.

Roone Arledge is credited with helping make “Monday Night Football” an entertainment spectacle and a financial success. Click for his book.

After the ABC deal was made, ABC producer Roone Arledge – who had already created ABC’s Wide World of Sports in 1961 – began to see big potential for the Monday Night Football program. Arledge is credited with turning the program into an entertainment and sports broadcast “spectacle” – expanding the regular two-man broadcasting team to three members; using twice the usual number of cameras to cover the game; using shots of the crowd, cheerleaders and coaches as well as closeups of the players; and instituting lots of graphics and technical innovations such as “instant replay.”

The first ABC Monday Night Football game – between the New York Jets and the Cleveland Browns in Cleveland – aired on Sept. 21, 1970. Advertisers were charged $65,000 per minute (a fraction of what they now pay ). The broadcast was a smashing success, collecting an eye-popping 33 percent of the viewing audience. Those numbers pleased the program’s early sponsors, such as the Ford Motor Company. Monday Night Football was on its way.

1971: “Monday Night Football” broadcast team of Howard Cosell, Don Meredith and Frank Gifford.

By 1971, however, Gifford replaced Keith Jackson as the play-by-play announcer on Monday Night Football (this trio is shown on the TV Guide cover at left). Thus began a nationally prominent role for Gifford that would last more than two decades in one role or another at Monday Night Football. Gifford, in fact, would become the longest-serving member of an ever-changing cast of characters on the Monday Night Football broadcast team – ranging from Alex Karas and Fran Tarkenton for periods in the 1970s, to O. J. Simpson, Joe Namath, Dan Dierdorf, and Michaels in the 1980s. In 1987, Gifford and Al Michaels – who had done the show as a twosome for two seasons – were joined by Dan Dierdorf. This Monday Night Football trio would last for 11 seasons, through the end of the 1997 season.

There were some memorable moments in the Monday Night Football broadcast booth, as on December 9, 1974, when the unlikely pair of former Beatle John Lennon and California governor Ronald Reagan entered the booth. Lennon was interviewed by Howard Cosell and Gifford was talking with Reagan, who later proceeded to explain the rules of American football to Lennon as the game went along, though off camera. Six years later on December 8th, 1980, during the Monday night game between Miami Dolphins and the New England Patriots, it would be Howard Cosell who announced a news bulletin to a stunned nation that John Lennon had been assassinated that night in New York city by gunman Mark David Chapman.

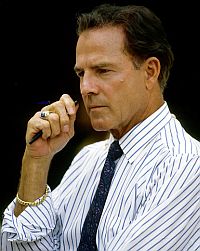

Frank Gifford, circa 1970s. |

August 1988: Gifford on the field prior to a Miami Dolphins - Washington Redskins game. |

In later years, there was some probing of the Monday Night Football empire, as a book by Marc Gunther and Bill Carter titled Monday Night Mayhem, reported that with Roone Arledge in control, the show was making lots of money for ABC, and its principals were treated well, with parties, limousines, and more. But by 1985, Monday Night Football was sliding in the ratings, beaten on occasion by Farrah Fawcett movies on NBC and other shows. Roone Arledge by then had moved on, and in the following year in the wake of the Cap Cities takeover of ABC, new management arrived. Gifford was moved out of his play-by-play role, replaced by Al Michaels.

But through it all, Gifford had a loyal following of viewers who liked him because of his low-keyed style, projecting a straight-arrow kind of guy, honest and sincere. Still, Gifford had his share of critics, some charging that he wasn’t critical enough of the players. “I don’t pay attention to the critics,” he said in a 1987 Los Angeles Times interview. “I have to please the audience… I know what I am. That’s more important than reading what others think. I know this game. I’ve always studied it, and I continue to do my homework.” Gifford added that he probably spent more time preparing to televise a game than he did preparing as a player. But the critics persisted, some calling his style boring or that he was too much of a company man.

“I’ve been accused of being everything from [plain] vanilla to being a shill for the National Football League,” he said in a 1994 interview with the Christian Science Monitor. “Some people think that you can’t be doing a good job unless you are bombastic and critical…. I don’t know where that concept ever came up in journalism.”

As for the “star” quality that may have come to the Monday Night Football broadcasters, Gifford sought to disabuse viewers of that notion.

In a September 1994 interview with Mark Kram of Knight-Ridder newspapers, Gifford explained that “the success of Monday Night Football has little to do with the announcers in the booth.” Rather, as Gifford then put it: “We are a success because football is the No. 1 sport in America, and that Monday evenings give people a chance to extend the weekend. I, as an announcer, can only reflect what has been placed on the stage, so to speak. We do not create it.”

Feb 1984 “GQ” cover featured Frank Gifford with story: “Gifford Keeps His Balance.”

Wide World of Sports

Gifford also appeared on other ABC sports programs, including Olympic Games coverage from 1972 to 1988, ABC’s Wide World of Sports, and he also did various sports personality profiles and TV specials. Gifford also put out another book in 1976 – Gifford on Courage: Ten Unforgettable True Stories of Heroism in Modern Sports – written with Charles Mangel. This book included profiles of sports figures, among them: Herb Score, Rocky Bleier, Charley Boswell, Don Klosterman, Floyd Layne, Charley Conerly, Y.A. Tittle, Dan Gable, Willis Reed, and Ken Venturi.

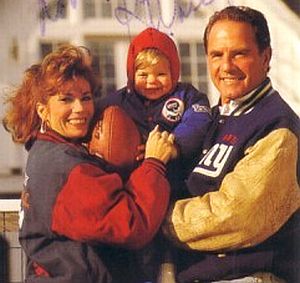

Gifford continued to be of interest as a sports celebrity and television personality, occasionally featured in magazines, such as the February 1984 GQ cover story shown at left (GQ, Gentlemen’s Quarterly, is a publication of the Newhouse family-owned Condé Naste publications). The GQ story was written by Frederick Exley, who had been following Gifford’s career since the days when both were students at USC. In television, Gifford sometimes appeared as a guest or a guest host on non-sports TV shows, including ABC-TV’s Good Morning America, where he met his third wife, Kathie Lee Johnson, a popular TV host. The two were married in 1986 and would have two children together. Throughout the late 1980s and the 1990s, millions of morning-TV viewers who watched ABC’s Live with Regis and Kathie Lee, would often hear Kathie Lee Gifford’s descriptions of life at home with her sportscaster husband and their two children. Gifford and his wife also appeared together on TV occasionally, as they did when hosting the nightly wrap-up segments on ABC during the 1988 Winter Olympics.

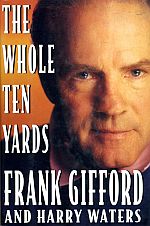

In 1993, Gifford published his autobiography, The Whole Ten Yards, with help from Newsweek’s Harry Waters. Kirkus Reviews called the book “a measured, straightforward, good-natured piece of work…”In the book, Gifford includes profiles of his former Monday Night Football colleagues Howard Cosell, Don Meredith, Dan Dierdorf and Al Michaels, calling Michaels at one point “the best play-by-play man in the business.” There are also profiles of Vince Lombardi, Paul Brown, and former teammates Sam Huff, Y.A. Tittle, Charlie Conerly, and Kyle Rote, as well as opponents such as Cleveland Browns running back Jim Brown, Chicago Bears tight end, Mike Ditka, and Philadelphia Eagles linebacker, Chuck Bednarik. The book also covers Gifford’s reminiscences of late 1950’s New York nightlife – all of which help to paint an engaging portrayal of New York football and its related social profile during that era.

In 1995, Frank Gifford was given the Pete Rozelle Award by the Pro Football Hall of Fame for his NFL television work.

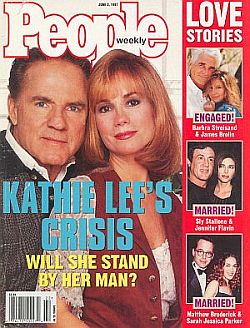

June 1997: People magazine featured the Giffords on its cover following the affair.

Gifford Affair

In May 1997, however, some of the luster of Frank Gifford’s famous career and celebrity became tarnished after it was revealed that he had an affair with a former airline stewardess, Suzen Johnson. A round of negative press followed, with magazine and tabloid front-page coverage, including a June 1997 People magazine cover story shown at left with photo and headline that read, “Kathie Lee’s Crisis, Will She Stand By Her Man?”

A November 1997 Playboy story also ran with Suzen Johnson on the cover. And some New York media talk shows and radio programs — including Howard Stern’s radio show, which had engaged in a running critique of Kathie Lee Gifford for years – also covered the story. Stern at one point threatened to air tapes of the tryst until the move was blocked in court.

It was later revealed that The Globe, the North American supermarket tabloid that originally broke the story, had arranged to have Gifford secretly videotaped being seduced by the former flight attendant in a New York City hotel room.

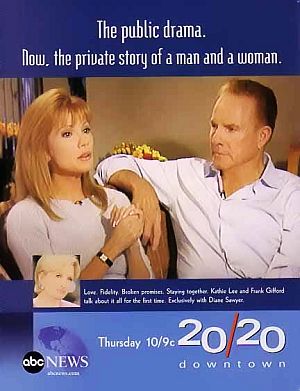

Tagline for ABC’s 20/20 show on the Gifford affair: “Love. Fidelity. Broken Promises. Staying together, Kathie Lee and Frank Gifford talk about it all for the first time. Exclusively with Diane Sawyer.”

Such incidents aside, however, the Giffords, throughout their careers, have been involved with various charities and social causes. Frank Gifford had served as chairman of the Multiple Sclerosis Society of New York and in 1984 the society established a $100,000 research grant in his name. And Kathie Lee Gifford regularly makes appearances at fund raisers and events for the non-profit organization ChildHelp, which works for the prevention and treatment of child abuse.

Still, the 1997 stewardess affair was a major blow to the Giffords and to Frank Gifford’s image. In 1998, following the incident, Gifford was given a reduced role on the Monday Night Football pre-game show. Boomer Esiason, 36, then the Cincinnati Bengals’ quarterback, quit active play to join the show. After that, and with 22 years of serving as a sportscaster there, Gifford left Monday Night Football, though he would continue to have other TV work. And on other projects, he focused on football history.

13 Oct 1963: Frank Gifford of the New York Giants about to catch a pass from quarterback Y. A. Tittle in game against the Cleveland Browns played in New York. |

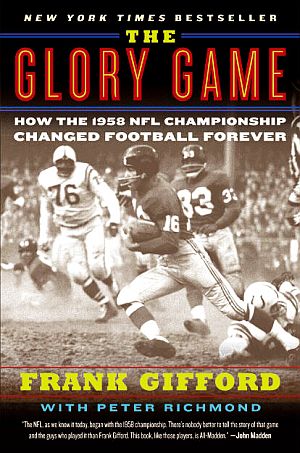

In 2008, Gifford published with Peter Richmond, The Glory Game: How The 1958 NFL Championship Changed Football Forever.

The book is Gifford’s account of the famous sudden-death overtime game between the New York Giants and Baltimore Colts in which he and 14 other later-elected Hall of Fame players and coaches did battle.

Gifford acknowledged that he had two costly fumbles in that game, but he also caught a pass for a key touchdown that had put the Giant’s in the lead, 17-14. Gifford was also at the center of a crucial 3rd down play with less than three minutes remaining in that game.

The Giants, then at their own 40 yard-line, needed four yards for a first down, which would have given them the game, as with a new set of downs they could have run out the clock. But on the 3rd down play, Gifford got the call, running the ball outside for a gain before he was tackled, though sure he made enough yardage for the first down.

In the play, there was some added commotion and distraction, as Colts lineman, Gino Marchetti, was calling out in pain after he had broken his ankle. Referee Ron Gibbs, who spotted the ball amid the concern over Marchetti, placed it short of the first down marker, and the Giants were forced to punt. That gave the Colts a chance to tie, and ultimately win, the game, which went into sudden death overtime.

But in his book, Gifford writes: “I still feel to this day, and will always feel, that I got the first down that would have let us run out the clock. And given us the title.” Gifford would later learn that the referee involved also believed he likely had made a bad spot.

See also at this website, “Bednarik-Gifford Lore,” an in-depth story built around the famous November 1960 gridiron collision between Gifford and Chuck Bednarik of the Philadelphia Eagles. For other sports stories at this website see the “Annals of Sport” page. Thanks for visiting — and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research and writing at this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

____________________________________

Date Posted: 5 January 2014

Last Update: 12 May 2020

Comments to: jdoyle@pophistorydig.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Celebrity Gifford: 1950s-2000s,”

PopHistoryDig.com, January 5, 2014.

____________________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

“Rough Day in Berkeley: A Zany Season Reaches Climax As Southern Cal Tips California Off Top of Football Heap,” Life (with photo sequence of Frank Gifford’s 69-yard run), October 29, November, 1951, pp. 22-27.

“Landry, Gifford and Rote to Pass For Giants in Game With Redskins,” New York Times, Sports, December 3, 1952.

“Revamped Giants to Face Steelers; Gifford Shifted From Defense to Offense for Contest at Polo Grounds Today,” New York Times, November 15, 1953.

“Gifford Drills 2 Ways; Giants’ Back Again May Play Dual Role Against Redskins,” New York Times, November 19, 1953

“Gifford at Quarterback For Giants in Workout,” New York Times, July 25, 1956.

“Conerly’s Pitch-Out to Gifford Rated as Key to Team’s Victory,” New York Times, October 29, 1956.

Louis Effrat/Ernest Sisto, “Giants Beat Eagles and Move into a First-Place Tie… Strong Defense Helps Giants Win …Conerly Passes Click; Gifford Makes Catch…,” New York Times, October 29, 1956.

Gay Talese, “Gifford Sandwiches Football Between Sidelines; Giants’ Top Ground Gainer Also Is a Movie Bit Player,” New York Times, November 4, 1956.

Louis Effrat, “Gifford Scores Three Touchdowns as Giants Beat Redskins Before 46,351; New Yorkers Win at Stadium, 28-14 Giants Avenge Earlier Loss to Redskins and Virtually Clinch Conference Title,” New York Times, December 3, 1956

Louis Effrat, “Giants Gain Title in East, Checking Eagle Team, 21-7; Capture Division Honors for First Time in 10 Years as Gifford Paces Attack ..,” New York Times, December 16, 1956.

“7 Giants Chosen on All-Star Club; Conerly and Gifford Among Players Named for Bowl Football Game Jan. 13,” New York Times, December 18, 1956.

“Gifford Named in Poll; Back Is Voted Pro Football’s Most Valuable Player,” New York Times, January 8, 1957.

William J. Briordy, “Gifford Receives a Rise in Salary; Football Giants’ Star Back Accepts $20,000 – Grier Is Inducted Into Army,” New York Times, January 29, 1957

“Giant Eleven Sends Lions to Their First Shutout Defeat in Five Seasons; Patton, Gifford Pace 17-0 Success; They Get Giant Touchdowns on Long Runs as Lions Lose Third Straight; Lions Fail to Threaten; Conerly Passes Click,” New York Times, September 23, 1957

“Up Periscope,” Wikipedia.org.

“Frank Gifford in TV Series,” New York Times, Thursday, January 21, 1960, p. 63.

Don Smith, The Frank Gifford Story, New York: Putnam,1960.

William R. Conklin, “Star Back Signed by Radio Station; Gifford Retires as Player but Giants Hope to Keep Him in Advisory Post,” New York Times, Friday, February 10, 1961.

“Frank Gifford Rates The NFL Running Backs,” Sport, October 1961.

Robert M. Lipsytet, “Gifford Returns as a Player; Giants’ Halfback, 31, Gives Up Duties as Broadcaster; Back Holds 3 Club Records,” New York Times, Tuesday, April 3, 1962, Sports, p. 48.

“Pro Football May Seem Tame to Giant’s Gifford After Thrill of Making TV Ads,” Advertising Age, 34(25): 64.

“Paper Lion (film),” Wikipedia.org.

Paul Wilkes, “Frank Gifford Talks a Good Game These Days,” New York Times, Sunday, December 14, 1969, p. D-27.

William Wallace, Frank Gifford: His Golden Year, 1956, New York: Prentice-Hall, September 1969.

Book Review, “Frank Gifford: The Golden Year, 1956, By William N. Wallace,” Kirkus Reviews, September 1969.

“History of Monday Night Football,” Wikipedia.org.

Frank Gifford, “Inside Monday Night Football,” Argosy, October 1973, Vol. 371, No. 10.

Frank Gifford and Charles Mangel, Gifford on Courage: Ten Unforgettable True Stories of Heroism in Modern Sports, New York: M. Evans & Co., September 1, 1976.

Philip H. Dougherty, “Advertising; Palm Beach Using TV And Gifford…,” New York Times, Thursday, June 22, 1978, Business & Finance, p. D-17.

Bert Randolph Sugar (Author) and Frank Gifford (Foreward), The Thrill of Victory: The Inside Story of ABC Sports, Hawthorn Books, 1978, 342pp.

“Planters TV Ads: Nuts & Snacks, Frank Gifford 1970s-1980s,” Duke University Libraries, Digital Collections.

Frederick Exley, “The Natural” (article on Frank Gifford), GQ, February 1984.

Michael Goodwin, “Sports People; Gifford Stays in Lineup,” New York Times, May 14,1986.

Martie Zad, “Frank Gifford: Monday Night Football’s Long-Distance Runner,” Los Angeles Times, December 6, 1987.

Steve Nidetz, “Gifford Goes Long In The Monday Game,” Chicago Tribune, October 23, 1988.

Frank Gifford and Harry Waters, Jr., The Whole Ten Yards, New York: Random House, 1993,

285 pp.

Tom Stieghorst, “Men Are Targets Of Carnival Cruise Lines Advertisements,” Sun Sentinel, April 10, 1993.

Steve Nidetz, “Gifford Book Serves Up Vanilla – But With Lumps,” Chicago Tribune, October 25, 1993.

Bill Fleischman, “Gifford’s Book Perfectly Frank,” Daily News (Philadelphia, PA) December 6, 1993.

Mark Kram, Knight-Ridder Newspapers, “They Were Giants During Their Playing Days And . . . They’re Still Giants In The TV Booth; Frank Gifford’s `Silver Spoon’ Image Belies His Childhood Out Of `The Grapes Of Wrath’,” Chicago Tribune, September 25, 1994.

Ross Atkin, “Energizing `Monday Night Football’,” Christian Science Monitor, December 22, 1994.

Jane Furse & George Rush, with Paul Schwartzman, Jorge Fitz-Gibbon & Phil Scruton, “Gifford Fling Bombshell Sleuth: I Was Asked To Tape Tryst,” Daily News (New York), Saturday, May 17, 1997.

Michael Hirsley, “Gifford Signs Off On `MNF’,” Chicago Tribune, January 17, 1998.

Richard Sandomir, “Pro Football; Esiason In; Gifford Moves,” New York Times, January 17, 1998.

Alex Beam, “Tabloid Law,” The Atlantic, August 1999.

Ed Sherman, “Gifford’s Long TV Run Ends Nearly Unnoticed,” Chicago Tribune, September 20, 1999.

Mike Puma, “Gifford Was Star in Backfield, Booth,” ESPN Classic.

“Frank Gifford,” Wikipedia.org.

Michael Starr, “Kathie Lee’s Pain Was a ‘Compliment’,” New York Post, May 4, 2000.

Mike Puma, “Versatile Gifford Led the Giants,” ESPN.com, Wednesday, November 19, 2003.

“Frank Gifford” (interview), Archive of American Television, September 2006.

Jack Cavanaugh, Giants Among Men: How Robustelli, Huff, Gifford and the Giants Made New York a Football Town and Changed the NFL, New York: Random House, 2008.

“Frank Gifford on What’s My Line,”(aired 12/2/56), YouTube.com, Uploaded, March 8, 2009.

Poseidon3, “One for the Gifford!,” Poseidon’s Underworld, Wednesday, August 3, 2011.

“Frank Gifford Gets Lucky” (What Happens in the Huddle?), Lucky Strike cigarette ad, YouTube.com, Uploaded by thecelebrated misterk, July 13, 2012.

“In The News – Frank Gifford” (list of stories), Los Angeles Times.

Mark Weinstein, “Frank Gifford: Icon” (Interview with Gifford), BlueNatic, Tuesday, August 20, 2013.

Frank Gifford Related Videos, Mashpedia .com.

“Planters Peanuts Commercial with Frank Gifford,” YouTube.com, Uploaded by spuzz lightyeartoo, October 3, 2011.

_____________________________