Famous “Earthrise” photo, taken from the Apollo 8 spacecraft then circling the moon, beamed to Earth on Christmas Eve, 1968.

Down on earth, however, technological progress was another story. More on that in a moment.

But on January 10th that year, a ticker tape parade was held in New York City to honor the Apollo 8 astronauts – James Lovell, Frank Borman and William Anders – who had recently returned from the first ever space flight to circle the moon, a prelude to the lunar landing later that summer.

The New York Times, reporting on the celebration in its January 11th edition, featured a front-page story with two photos, one with Mayor John Lindsay and Governor Nelson Rockefeller congratulating the astronauts.

Apollo 8 was also the flight from which the famous “Earthrise” photograph was taken. That historic photo had captured the lone, beautiful, blue-ball object that is the home planet, floating singularly in the black void of space, suggesting this was, possibly, the only life-sustaining planet out there, and that we, its occupants, ought to take care of it. Yet on that same fragile, blue ball, the record of mankind’s earth keeping had not been very good to that point.

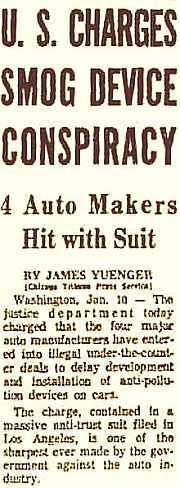

January 11, 1969 front-page New York Times story reports on a Justice Department lawsuit alleging an automaker conspiracy on anti-pollution technology for automobiles.

That story, with a Washington D.C. dateline, reported that the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) had brought an anti-trust lawsuit against American automobile companies for conspiring to hold back and delay the use of pollution-control devices for motor vehicles.

The suit would come to be called the “smog conspiracy” case, as it alleged that Detroit’s then “Big Four” automakers – American Motors, Chrysler, Ford, and General Motors, along with their trade group, the Automobile Manufacturers Association (AMA) – had conspired for sixteen years (1953-1969) to prevent and delay the manufacture and use of pollution-control devices for automobiles.

The DOJ lawsuit made front-page news all across America, and potentially was a very major federal action against some of the world’s most powerful corporations. At stake, was nothing less than clean air and public health.

Chicago Tribune story on the smog conspiracy lawsuit, January 11, 1969.

In other words, if the DOJ charges were correct, during the 1953-1969 period, millions of motor vehicles were produced without known pollution-control devices and/or known pollution-control fixes. This meant that millions of tons of auto pollutants were being dumped into urban and rural environments for more than a decade – pollution that could have been prevented – thereby harming public health and causing crop and property damage. Or looked at another way, the “breathable common” was subsidizing auto production.

The Detroit automakers and their trade association vigorously denied DOJ’s allegations. Much of the lawsuit hinged on a 1953 cooperative agreement made among the automakers to jointly research auto pollution and pollution-control technologies – with subsequent and ongoing joint auto company and AMA committee meetings under that agreement during the 1953-1969 period.

However, what DOJ billed as a conspiracy to hold back technology, the automakers claimed was industry cooperation and joint research to ensure technological advance.

Yet for some, the proof was in the pudding, as they say, since few technological advances in automobile pollution control had actually made their way to new vehicles during the 1953-1969 period. More on the legal battle and outcome after a bit of background.

L.A. Smog

The 1969 smog conspiracy case had its origins in Los Angeles, California, a city that had been choking on smog since the early 1940s – though its residents and officials then knew little about what smog really was or how it formed.

Yet this smog – a word formed by a contraction of “smoke” and “fog” – was new and different. There were days when a “pall of haze” would form over the city, as residents noticed that its peculiar yellowish-brown color was different and not benign. The soup would burn the eyes and sear the lungs. One of the first “smog days” came in the summer 1943, when visibility in some places dropped to three blocks, and hospital emergency rooms had visits from those suffering with burning eyes and lungs.

Early 1940s photo of highway leading into downtown Los Angeles, with smog forming over the city there, showing the tall landmark L.A. City Hall building at center in the distance.

Then came an episode of September 8, 1943, called a “daylight dimout” when even sunlight was diminished. “Everywhere the smog went that day,” reported the Los Angeles Times, “it left a group of irate citizens. . . Public complaints reverberated in the press. . . . Elective officials were petitioned.” Indeed they were, and some actions followed. A spate of laws and commissions came into being.

The Los Angeles County Air Pollution Control District, established in 1947, was the first of its kind anywhere in the nation. By 1948, L.A. had targeted smokestack industries like oil refineries, foundries and mills, and later, backyard incinerators. But the smog persisted. Autos, for the most part, were not obvious smoke-belching contributors, with exhausts that were mostly invisible and thought to play only a minor role in the smog problem.

January 5, 1948. Smog formed in downtown Los Angeles, with City Hall building to the left. UCLA photo.

Then, in the fall of 1949, there was an event that occurred hundreds of miles north of L.A., at a University of California-vs-Washington State football game in Berkeley that offered some fairly convincing “cause-and-effect” clues. There, a fairly intense pollution event occurred at the stadium, which later led state legislators to investigate.

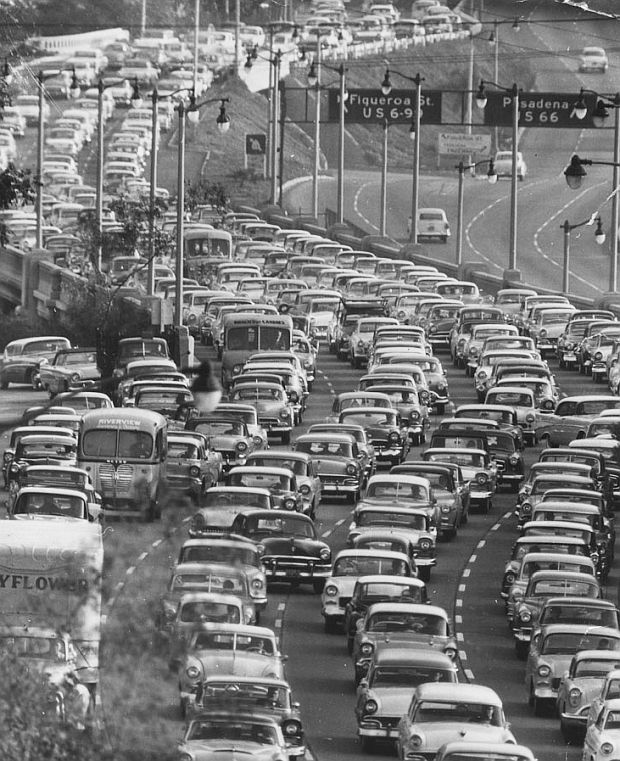

On the day of the game that fall, thousands of fans drove into Berkeley with resulting traffic congestion. Later that day, during the game, after the soup had formed, the pollution became so bad that “many thousands of persons attending . . . experienced intense eye irritation.” Game-day pollution at a 1949 Berkeley football game implicated autos – later seen as a microcosm of L.A. smog. Later, in the California General Assembly, the Committee on Air and Water Pollution investigated the incident, noting that the only unusual occurrence that day “was the concentration of automobiles at the football game in Berkeley, accentuated by the idling of motors, starting and stopping, which occurs in such a traffic jam.” There was no other industrial or other source in the area. It could only be concluded, the committee said, “that the cause of this particular eye irritation was in some way directly related to automobile exhaust.” In fact, the committee suggested that the pollution in Berkeley that afternoon was really quite similar–“very striking” in their words–to what was occurring in Los Angeles on a daily basis. The game-day traffic in the stadium area, they suggested, was actually a microcosm of what was happening over a much larger area in Los Angeles, where “the crowding of existing freeways leading to the downtown area results in daily traffic jams as the flood of cars enters the city in the morning, with resulting accentuation of the exhaust problem by idling, stopping, and starting.” Although there was little hard science to verify their hunch, they believed that vehicle exhaust, from auto combustion engines, was certainly contributing to the LA pollution problem.

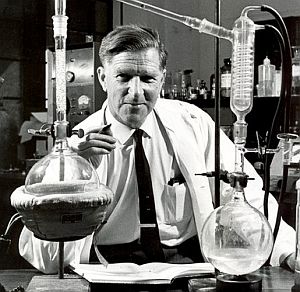

Dr. Arie J. Haagen-Smit, discovered that the sun “cooked” certain auto pollutants in a photochemical reaction to make ground-level “ozone,” an unhealthy pollutant.

Meanwhile, back in L.A., one inquisitive scientist, Dr. Arie J. Haagen-Smit, a professor of biochemistry at the California Institute of Technology, had begun researching the region’s air pollution. Haagen-Smit, initially working on how air pollution was damaging crops, began in 1950 researching how smog actually formed.

Haagen-Smit made an important discovery – that unburned hydrocarbons and nitrogen oxides, coming primarily from automobile exhaust and some industrial sources, were “cooked” by sunlight in a photochemical reaction to form ground-level ozone, later revealed as a respiratory irritant.

Breathing ground-level ozone can trigger chest pain, coughing, throat irritation, and congestion. It can worsen bronchitis, emphysema, and asthma. It can also reduce lung function and inflame the lining of the lungs. Repeated exposure may permanently scar lung tissue.

As Haagen-Smit’s ozone findings emerged, there was some finger-pointing initially among those in the auto and oil industries, as to whose sources were the bigger culprits. But it soon became clear that the region’s burgeoning auto population was central to the smog problem. By 1954, L.A.’s two million cars were racking up 50 million miles of travel every day. Episodes of dense smog in the L.A. area continued. On one occasion in 1954, the smog was so bad that it reduced visibility to the point where some 2,000 auto accidents occurred in a single day. Life magazine, the popular American weekly of that era, did a brief November 1954 story on L.A. smog titled, “Blight on the Land of Sunshine,” with photos of the city shrouded in smog and citizens in protest clamoring for action.

1956. Traffic on the Pasadena Freeway, which connects L.A. with Pasadena, captures the growing population of motor vehicles then in the L.A. region, where “vehicle miles of travel” for its then 2 million-plus vehicles, was exceeding 50 million miles every day.

By the mid-1950s, Dr. Haagen-Smit’s findings on the connection between automobiles and smog in Los Angeles became widely accepted in scientific circles – but not in most auto industry circles, at least not publicly.

In fact, as Los Angeles authorities began closing in on the automobile as major smog contributor, the auto industry doubled down and began its “denial-and-delay” campaign that would continue in one form or another for the next 50 years – not only in LA., but nationally as well. But it was in L.A., where the automakers made their earliest stands of denial and obfuscation.

1956 photo of smog in downtown Los Angeles, with the City Hall building at center.

First, the industry insisted on definitive proof that autos were the cause of L.A. smog. General Motors had already written in March 1953, for example, that while Los Angeles studies indicated that exhaust gases “may be contributing factor to the smog,” other cities did not appear to have the same problem. Thus, for GM, “some other factors,” peculiar to Los Angeles, “may be contributing to this problem.” Ford officials, also writing in March 1953, had taken the view that exhaust vapors from automobiles “dissipated in the atmosphere quickly and do not represent an air pollution problem.” Ford officials contended that the need for a device “to more effectively reduce exhaust vapors had not been established.”

Next, after the automakers conceded in 1954 that the automobile was the largest single source of hydrocarbons in Los Angeles, and that auto exhausts were capable of forming ozone, industry officials wanted further work to substantiate the exact cause-and-effect relationship between auto pollutants and smog. In 1955, the automakers held that the evidence did not prove auto pollutants produced smog and its harmful effects, such as eye irritation and crop damage, etc.

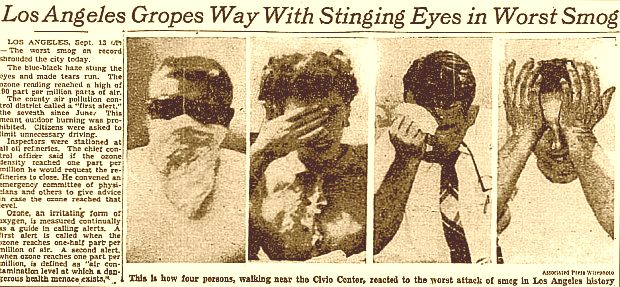

September 1955. Front-page New York Times story on Los Angeles smog showing four people reacting to the pollution who were walking near the L.A. Civic Center. The city was then experiencing one of its worst bouts of smog on record.

In 1957 when definitive proof was found that the automobile was the primary cause of photochemical air pollution, the automakers reverted to an earlier held position that the smog problem was peculiar to Los Angeles. It continued to espouse this view for three more years.

By 1959 the state legislature passed laws, making California the first to establish air quality standards based on the public health effects of smog. But progress was slow. “Eye irritation” that year was reported in Los Angeles on 187 days; by 1962 it was 212 days.

Headline from Sept 1958 L.A. Times story on a smog alert, a headline that would become all too common in the region during the 1950s-1960s period – and beyond.

Photochemical smog, Richards explained, was only caused when the unique combination of all the L.A. factors came into play: persistent temperature inversion, encircling mountains, very light wind movement, and intense sunlight. Further, photochemical smog, he said, “is not likely to occur anywhere else on earth with the frequency and intensity found in this area.” Richards added that the auto industry would not consider controls on its vehicles in other parts of the country until it was demonstrated that hydrocarbons presented a problem elsewhere.

Yet automobile-fed air pollution was occurring in other cities across America. “Los Angles-type smog” was being reported in New York, Philadelphia, and other cities by the late 1950s, also spreading to rural areas in some locations. Commercial airline pilots in the 1950s and 1960s reported seeing the skies over broad regions of the U.S. becoming less and less clear — and not just over urban areas.

|

“They Have a Responsibility” In February 1953, Kenneth Hahn, a Los Angeles County supervisor, wrote a letter to Henry Ford II to ask what Ford’s company knew about automobile pollution and what the company’s research plans were. Mr. Ford replied, through his staff, that there was really no problem, and therefore, no need for research. “The Ford engineering staff, although mindful that automobile engines produce gases, feels that these waste vapors are dissipated in the atmosphere quickly and do not present an air pollution problem,” replied Ford’s public affairs manager, Dan J. Chabak. “Therefore, our research department has not conducted any experimental work aimed at totally eliminating these gases.” Hahn was later assured by Detroit that an industry wide study of the exhaust problem had begun. Mr. Hahn, however, kept writing, pushing for action.  Ken Hahn, L.A. official. In January 1964, when Hahn testified before two U.S. Senate committees, he handed out a little booklet of the collected correspondence he had made with the automakers, explaining to the senators: . . . I have tried to tell [the auto executives]. . . that they have a responsibility on air pollution and they have not met it. . . . . . . [T]hey know about the problem. . . .They have been here; there are devices manufactured that have been proven. . . . [A]nd it is strange why they have not put it on all their cars. . . . . . . Now they have had ten years of warning, all documented with answers back from their own officials saying they are studying the problem and researching it. They can research this to death; in the meantime we haven’t licked the problem. . . It would not be until 1966–thirteen years after Mr. Hahn began his inquiries of the automakers–that exhaust controls would be required on new California cars. And even then, it would only be by force of law. Meanwhile, Ken Hahn’s 1953-1967 correspondence with the automakers leaves behind a record as good as any on the industry’s attitudes on pollution control at the time. |

Birth of Lawsuit

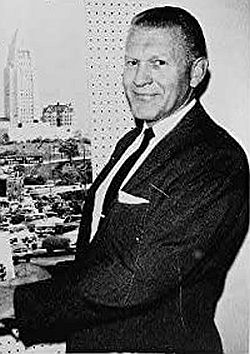

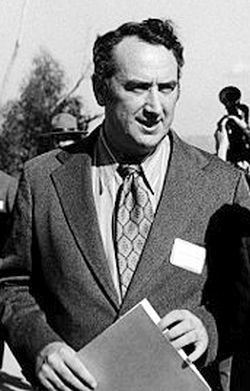

1959 photo, S. Smith Griswold, L.A. County

Another L.A. official, S. Smith Griswold, the Chief Air Pollution Control Officer for the L.A. Air Pollution Control District since 1954, had been quite critical of the auto industry’s lack of progress on pollution. “Patent data,” Griswold once said, “shows that automobile pollution controls were available as far back as 1909.”

But in June 1964, Griswold, by then L.A. County Pollution Control Board executive, gave a speech at the annual meeting of the Air Pollution Control Association. Griswold recalled that in 1953 the automakers had made a joint cooperative agreement with one another, supposedly to pool their research on air pollution and come up with a solution.

The automakers said they would make progress jointly and even set up cross-licensing agreements to insure that progress by one would be progress by all. But a skeptical Griswold wondered what they had actually come up with.

Ralph Nader helped L.A. officials see legal action against the auto-industry.

Griswold had hit upon a possible antitrust issue that was later driven home to him by Washington, D.C. attorney Ralph Nader, who was then beginning his career as a leading consumer advocate. In addition to alerting Griswold of the possible auto industry collusion, Nader also briefed Justice Department officials on what he thought was the basis for a major antitrust suit.

Griswold then drafted a resolution for the LA County Board of Supervisors citing the auto industry’s lack of progress on pollution-control technology.

The resolution, adopted in January 1965, specifically requested the U.S. Attorney General to initiate an investigation and take legal action to prevent the automakers from engaging in “further collusive obstruction.” By this time, the Justice Department had already subpoenaed records from the industry, and a formal investigation was underway. But the full pursuit of the case would take several years

During 1967-68, as the DOJ case moved forward, an eighteen-month grand jury investigation was convened in Los Angeles. The smog in L.A., meanwhile, had not abated, and was a continuing problem.

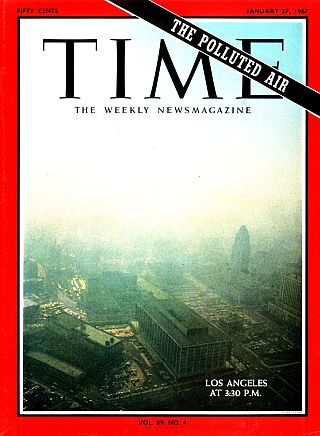

January 1967. Time magazine featured a cover photo of a smog-shrouded Los Angeles, around the time the DOJ grand jury investigation began in the automaker conspiracy case.

“Instead of disappearing… Los Angeles’ characteristic whisky-brown smog has actually grown worse. The culprits are Los Angeles County’s 3.75 million autos, which produce 12,420 of the 13,730 tons of contaminants released in to the air over the county every day [emphasis added]… In addition to nearly 10,000 tons of carbon monoxide, autos exhaust 2,000 tons of hydrocarbons and 530 tons of nitrogen oxides daily, enough to form a substantial brew of irritating smog.”

Back inside the Justice Department, attorneys handling the conspiracy case had initially sought a criminal indictment, but “higher ups” hedged and delayed action. As the case evolved, there was debate over whether the grand jury should seek a criminal or civil indictment. The civil route won out.

Four federal judges who might receive the case were strongly opposed to criminal sanctions in antitrust cases. In addition, it had been long-standing Justice Department policy to reserve the criminal route for price-fixing and other traditional cases in which there was

no question of blatantly illegal conduct.

However, this auto pollution case was not traditional. Some, like Ralph Nader, argued for “product fixing;” that restraint of technology was restraint of trade, preventing competition. This, however, was a very novel approach at the time, especially in the conservative world of antitrust litigation.

D.C. attorney, Lloyd Cutler, post-1960s photo, represented auto industry in smog case and helped negotiate DOJ consent decree.

Lloyd Cutler, then a well-known and respected 51 year-old attorney at the Washington, D.C. law firm of Wilmer, Cutler and Pickering, was representing the Automobile Manufacturers Association (AMA).

Cutler, in fact, had been in and out of meetings at the Justice Department for weeks during 1969 on the smog conspiracy case, negotiating on behalf of his clients. By late summer 1969, there came rumor of a deal on the smog conspiracy case.

Sure enough, on September 11th, 1969 – nine months after the case was filed – the Justice Department announced that the case would be settled by consent decree. In the legal trade, consent decrees are viewed as a way to save face, save cost, and not drag all the parties through a public display of charge and countercharge. For the automakers, that was good news. There would also be no findings or admissions of illegal activity.

Fight The Decree

September 1969 New York Times story on proposed consent decree.

A key issue became the evidence compiled by the grand jury investigation. Under the consent decree, that evidence would be sealed forever. However, if the case were brought to trial, and the defendants found guilty of conspiracy, under the antitrust laws, any injured parties could then bring their own suits to recover three times the damages suffered. Triple damages are designed to serve as a deterrent to future violations, and in this case, future conspiracies against the public good.

Earlier on Capitol Hill, as rumors swirled about a settlement, a group of nineteen congressmen, led by Reps. George Brown (D-CA) and Bob Eckhart (D-TX), sent a letter to Attorney General Mitchell expressing their concern that a full trial was needed to show the public that corporate law breaking was no different than any other violation of law. The Justice Department, nevertheless, proceeded with its agreement.

In Los Angeles, meanwhile, Supervisor Kenneth Hahn told the press that Los Angeles County would demand the unsealing of “a roomful of federal grand jury evidence” gathered by the grand jury. According to Hahn, the foreman of the grand jury, Martin Walshbren, was quite angry over the Justice Department’s consent agreement. In fact, when asked by a Los Angeles Times reporter if there was more to the case than the consent decree suggested, Mr. Walshbren said, “Yes,” there was, “a great deal more.” Walshbren also believed an indictment of some kind would have been brought by the grand jury if DOJ had sought one.

L.A.’s Kenneth Hahn wanted a trial. “The presidents of General Motors, Ford, and Chrysler should be brought to trial right here in Los Angeles. . . . The big manufacturers all conspired. If one wouldn’t put the devices on, the others wouldn’t either. . . . This case is the most important legal battle in the history of the air pollution fight. If we lose it, we will go back twenty years.” California attorney general, Thomas Lynch, planned to file a separate antitrust action against the auto companies, but said he too was being hampered by the seal on the grand jury records. He was unable to question key grand jury witnesses.

“The presidents of General Motors, Ford, and Chrys-ler should be brought to trial right here in Los Angeles. . . The big manufacturers all conspired.”

– Kenneth HahnStill, there was one last chance for those opposing the settlement, as the consent decree had to be approved by a federal judge. A brief but intense campaign to prevent the approval of the decree followed. Thousands of individuals, scores of congressmen, and numerous municipalities petitioned Federal District Court Judge Jesse W. Curtis not to approve the decree. Other related developments at the time included the following:

> the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors asked the federal courts to allow them to intervene in the original suit and to sue the manufacturers for $100 million in damages. At the time, other municipalities were also being asked to join Los Angeles in the intervention. With other parties joining the case, it was thought that the court might be reluctant to agree to the settlement before holding an open trial.

> members of the Judiciary Committees in both Houses of Congress were asked to sign a letter urging the Justice Department to review its whole policy towards the use of consent decrees in antitrust cases.

> Rep. George Brown (D-CA) started a statewide petition drive requesting the Justice Department to withdraw the settlement, and he also introduced a four-part resolution in the House, part of which requested the full transcript of the 1966-67 grand jury investigation, including subpoenaed documents.

October 1969 NY Times story on the smog decree’s final approval.

Following the consent decree’s approval, there was a flurry of legal actions related to the DOJ case that continued through mid-1973. Some twenty-eight states and another ten cities and counties brought private actions against the automakers after the federal case was settled. These actions, modeled on DOJ’s antitrust case, sought damages for automotive air pollution. Later consolidated into one case in California, the suits sought a variety of remedies, asking, for example, that auto companies be ordered to take steps to eliminate smog, make contributions toward the establishment of mass transit systems, and provide free emissions testing of automobiles.

In June 1973, the U.S. Court of Appeals in San Francisco ruled that the plaintiffs could not sue for damages in the case but they could seek equitable protection under the antitrust law. However, in October 1973, Federal Judge Manuel Real dismissed thirty-four of the thirty-eight cases saying that the antitrust laws did not give him the power to force the automakers to find a solution to the pollution problem. The automakers argued that antitrust laws were reserved for the regulation of business conduct and the adjudication of business damage. The cases brought, they argued, were not about business damage in the strictest sense of antitrust tradition, as in price-fixing. Judge Real agreed. He explained, this was “not the result of any conspiracy or combination in restraint of trade.” The antitrust laws, he explained, “are not intended–nor do they purport to be–a panacea to cure all the ills that befall our citizenry by the accident that some damage or injury may have been caused by a business enterprise.” The suits had asked the judge to depart from traditional antitrust law to “find a solution to this most perplexing social problem.” Some later speculated that the states might have fared better had they pursued a public nuisance argument rather than mimicking the federal government’s antitrust case.

Phil Burton’s Disclosure

In 1971, U.S. Rep. Phil Burton revealed DOJ memo from the “smog conspiracy” case.

“The disclosures are especially painful in light of the settlement of the government’s civil case . . . ,” said Burton, submitting the DOJ memo to the public record on the floor of the U.S. House of Representatives, where he was immune from prosecution for revealing court-sealed documents. The settlement, in Burton’s view, “deprived the public of an open trial on all the issues;” a trial that he believed would deter the auto industry from technological collusion at the public’s expense. Burton urged Attorney General John Mitchell to reopen the case, conduct both a Justice Department investigation and convene a new grand jury to consider a conspiracy indictment–none of which ultimately occurred. Yet Burton was especially interested in an investigation to determine whether the alleged conspiracy was continuing. “All indications since the consent decree was approved point to the dismaying fact that nothing has changed,” Burton said. “The automobile companies continue their carefully orchestrated united front — claiming in every public, hearing and in every public docket that they can’t meet the deadlines for anti-smog devices.” (By then, in fact, the 1970 Clean Air Act had been passed by Congress with set auto emissions deadlines that the auto industry also fought).

Yet, Burton’s disclosure of the DOJ memo brought new evidence to the public record, showing how the auto industry and its trade association dealt with the growing auto pollution problem during the 1953-1967 period; how they maneuvered to hold back and delay pollution control technologies even while assuring public officials they were going all out to develop those technologies. Some of the technological delay the DOJ memo reveled follows below.

Crankcase Pollution

Bluster on Blow-By

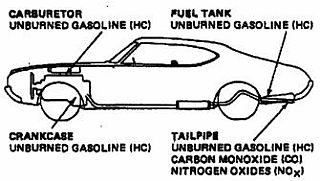

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, three parts of the automobile were seen as the primary targets for addressing pollution: the crankcase, the carburetor/fuel tank, and the exhaust system. At the time, experts estimated that 25 percent of the pollutants came from the crankcase, 15-to-25 percent from evaporation losses at the carburetor and fuel tank; and 50-to-60 percent the engine’s exhaust.

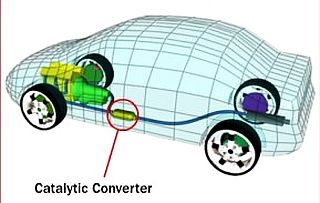

Generalized graphic showing three major areas of auto pollution - crankcase, carburetor/fuel tank & exhaust system.

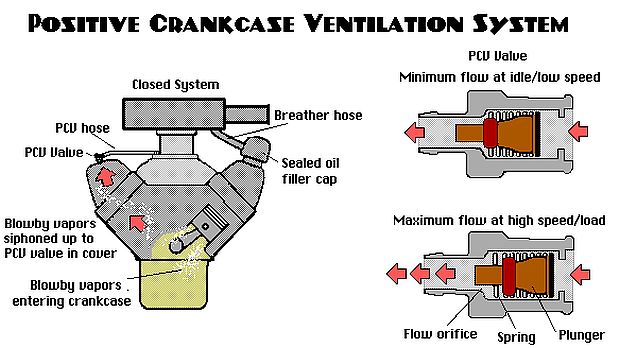

Engine graphic at left shows crankcase pollutants being recirculated for recombustion. Yet for decades prior, crankcase pollutants were simply released from the bottom of the engine through a vent pipe to the road below and into the atmosphere. There were no controls – or at least none in use for most vehicles.

Neither “positive crankcase ventilation,” nor the PCV valve itself, were new concepts or technological breakthroughs. PCV valve was known about since the 1940s – and the principle of vacuuming off the gases from the crankcase back to the carburetor or intake manifold for recombustion – long before that. Howe Hopkins, an industry old-timer, former federal emissions official, and long-standing member of the American Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE), offered this account in 1969:

“. . . From 1921-1923, Ludlow Clayton of the Sun Oil Company wrote numerous papers for the SAE Journal on drawing crankcase gases out by creating a small vacuum. Back in about 1936, I went down to the Studebaker plant to meet W.S. James, the company engineer who demonstrated for me a simple tube attachment from the crankcase to the intake manifold to recirculate and recombust the crankcase gases. They were offering a conversion kit for this which was essentially only a length of copper tubing. . . .”

Although certainly by the early 1950s there was sufficient understanding of crankcase blowby, some in the industry would portray crankcase ventilation as a new development. Almost magically, 1959 had become the year industry “discovered” what to do with crankcase pollutants. “In 1959, through a truly extraordinary stroke of good fortune,” reported one account from the AMA “–the crankcase was discovered to be a more important source of emissions than had been suggested by prior government and other studies.”

Auto industry officials, then eyeing possible statewide regulation in California with strong pressure from local officials in Los Angeles, soon began to see that installing the relatively simple PCV device on California cars might be a way to forestall even tougher regulation by the state.

Exhaust Devices

Catalytic Reaction

By the late 1950s, California had signaled its intent to the auto industry that exhaust-treating devices might be required. The automakers, however, were known to be less than excited by such a prospect. “They [the Big Three] are not . . . interested in making or selling devices. . . ,” wrote Dr. Donald Diggs, a technical manager at Du Pont, in an April 21, 1959 report. “[B]ut are working solely to protect themselves against poor public relations and the time when exhaust control devices may be required by law.”

Graphic showing placement of catalytic converter in the exhaust system to treat engine pollutants, exiting tail pipe. |

Cut-away drawing of later-developed catalytic converter, in this case converting engine pollutants HC, CO, and NOx to water and CO2 after passing through a treatment medium. |

In May 1959, Ford’s James Chandler took the position that the smog problem “is not bad enough to warrant the enormous cost and administrative problems of installing three million afterburners.” Chandler, in fact, believed that one of the functions of the AMA working group was to “contain” the smog problem.

J.D. Ullman, another Du Pont technical expert working on auto-related issues noted in April 1960: “We gathered that the automobile industry will continue to do whatever it can within the scope of California legislation and of political pressure to postpone installation of exhaust control devices. . . .” An official of the Maremont Automotive Products Co., also doing business with Detroit, confided to a Du Pont colleague in May 1960 that the automakers “were keeping up a good front, but were not pushing as rapidly as they could toward a solution of the smog abatement problem.”

What the automakers feared most, however, was that some outside interest might begin to meddle in the core of their business in a way that could affect control over what was produced. This fear surfaced as a new group of businesses began working on catalytic devices to be installed in exhaust systems to treat and reduce auto pollution.

Catalysts are substances used to facilitate a chemical reaction without themselves being consumed in the reaction. By the time catalysts were being considered for pollution control in the auto industry, they had been used for years in various industrial processes. Catalysts applied as a remedy to the exhaust fumes of gasoline engines were first used in the coal mining industry to deal with the carbon monoxide problem in enclosed spaces. In the 1920s, researchers at Johns Hopkins and the U.S. Bureau of Mines produced a substance called “hopcalite” to control CO. Separately, in fact, Johns Hopkins researchers had applied the substance to automobiles about the same time and published a research report about the attempt.

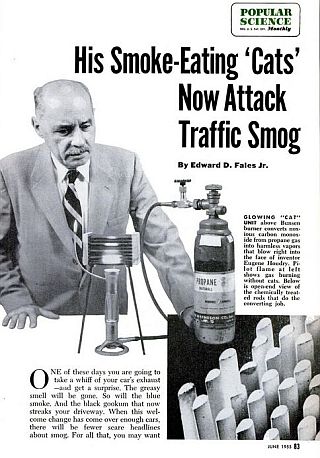

June 1955 Popular Science story highlighting some of the early catalytic converter research of Eugene Houdry.

Later concerned with possible health risks of automobile and industrial air pollution, Houdry started the Oxy-Catalyst Company, and would build early, generic catalytic converters capable of reducing carbon monoxide and unburned hydrocarbons from auto exhaust.

A June 1955 Popular Science story, shown at right, highlighted Houdry’s work with catalysts to control pollution, suggesting they would soon come to automobiles. In 1956 Huodry received a U.S. patent for his early automobile catalytic converter design.

Detroit, however, was never keen on catalytic devices, especially those made by outside firms. The automakers would do all in their power to delay the day such devices would be required.

True, in 1957 Ford Motor had tested and bragged about its vanadium pentoxide device to the press – (a move that brought Ford a rebuke from its co-conspirators for violating the industry agreement of a united front). Ford’s device, in any case, was an early, crude version of a catalytic converter; so big and cumbersome that some speculated it was purposely put forward to show that such exhaust-treatment devices wouldn’t work.

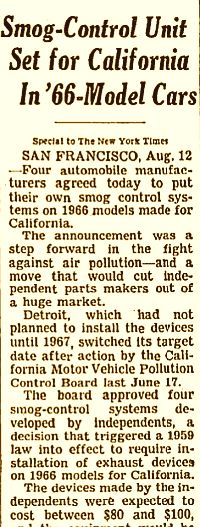

August 13, 1964 NY Times story.

The operative “trigger” for setting in motion the state’s requirement for installing exhaust controls was state certification of any two new devices. One year following such certification, automobiles then sold in California would have to be equipped with one or the other device. By the end of 1963 and early 1964, it was clear that two devices being produced by non-auto manufacturers would be certified, thereby triggering the law, and requiring their installation on all 1966 models. At the AMA, meanwhile, a March 1964 memorandum from William Sherman, offered a strategy for how the automakers might gain a one-year delay. Ford was also maneuvering at the time to say it could only meet a 1967 model-year goal.

California, however, did not blink in the face of industry’s delay gambits. The MVPCB notified the automakers that the state was testing four exhaust control devices on an accelerated basis. MVPCB’s chairman, J. B. Askew indicated the board was hopeful industry “would work with us to achieve exhaust controls for 1966 models.” In June 1964, the board approved four exhaust devices manufactured by nonautomotive manufacturers. In July, it requested Detroit’s plans for meeting the 1966 model-year requirement. On August 12, 1964, the automakers formally presented their intentions to comply with the 1966 model-year deadline.

As it turned out, however, none of the automakers used the approved catalytic devices developed by the outside manufacturers. What emerged in place of the catalytic devices was a “combustion control” approach Chrysler had known about since 1957 – something called the “Clean Air Package.” (The catalytic converter debate would resume once the federal 1970 Clean Air Act was passed by Congress, as converters were eventually used to help meet those standards).

Engine Tinkering

Clean Air Package

However, Chrysler’s Clean Air Package (also billed as “The Cleaner Air Package” in some accounts), was not exactly rocket science. The “system” for controlling exhaust emissions had two essential elements: more complete combustion and retarding the spark. These fixes were accomplished by adjusting the fuel/air ratio reducing the amount of gasoline burned, thereby reducing the amount of unburned, polluting gases; and adjusting the timing of the spark at the combustion chamber, which had the net effect of making the engine run at higher temperatures, thereby burning up some of the exhaust gases outside the combustion chamber. This, however, was not new technology.“The technological breakthrough that is the Clean Air Package,” concluded Ralph Nader’s Task Force in Vanishing Air, “consists generally of . . . [a] different rubber hood seal, different cylinder gaskets, reduced production tolerances, and a different manifold heat valve. The carburetor and distributor employ very simple control valves.”

Auto industry veteran, Howe Hopkins, would explain of the long-known engine adjustments: “I knew about the effect of retarding timing on combustion efficiency in 1925,” he said. “But of course, others knew about it before that. The Model-T Ford had a manual device so that the owner could advance or retard the spark. . . .”

All told, concluded the Nader Task Force, “the Clean Air Package can hardly be heralded as a breakthrough in the annals of automotive history.”

It also became apparent that the adjustments in engine timing and spark used as a pollution-control strategy in the Clean Air Package were highly dependent upon regular maintenance and adjustment to local driving conditions to consistently reduce pollution.The Clean Air Package was not new technology; it consisted of engine adjustments known since the 1920s and deteriorated with use. Chrysler’s “package” deteriorated with use and would not cut pollution in 50 to 80 percent of operating vehicles. Engine adjustments made for cars in Los Angeles weren’t necessarily appropriate for stop-and-go driving in major cities of the northeast. The CAP and CAP-like systems also caused the engine to produce higher temperatures by combusting excess gases in the engine compartment, and with that, other pollutants began to form, and most notably, nitrogen oxides (NOx), a chief component of photochemical oxidants, or smog. NOx was then not regulated, so for industry, it did not figure into the pollution control fix at the time. Still, industry knew about the NOx problem at this juncture and knew it would be a problem going forward, but proceeded essentially to engineer around it. But for the auto industry, the CAP was a masterpiece of strategy; it was a low-cost, Band-Aid application when something more like a tourniquet was needed

In any case, GM, Ford, and American Motors eventually adopted the Chrysler CAP, or approaches similar to it, for their 1966 model year cars as well. As for the emerging catalytic converter industry, once it was learned that Chrysler’s Clean Air Package would be certified by California in 1964, most of the outside companies engaged in making catalytic devices either stopped or shelved their programs. CAP-like systems would also be used nationwide and would continue to be the primary “technology” used to control auto pollution, though quite poorly, through the early 1970s.

1968 General Motors print ad. “Air Pollution? They Never Heard of It.” Once basic pollution control devices and simple engine adjustments began to be used, GM sought to publicly tout its role in reducing pollution, although also, as in this ad, instructing drivers on their maintenance role.

Much Longer Story

The revealed 1950s-1960s technological foot-dragging by the auto industry, and the travail of the failed DOJ smog conspiracy case, are only a small part of the much longer story of automaker maneuvering and recalcitrance on auto pollution, fuel economy, safety, and alternative engine technology. It’s a story that continued through the 1970s, 1980s, 1990s and beyond — and in fact, continues to this day in the current climate debate.

Following the smog conspiracy case, the automakers discovered they didn’t need to conspire to hold back technological improvements. Rather, their lobbying, political muscle, economic leverage, legal firepower, and public relations campaigns were typically sufficient to thwart the needed technology, whether for pollution-control, fuel economy, or alternative engine development. This is evident from the now 60-year record of their participation in the public policy arena, in which they were able, repeatedly, to water down, extend, delay, and/or subvert emissions and fuel economy standards and deadlines. Indeed, one GM official would later boast that in terms of the original 1970 Clean Air Act’s auto emission goals, “ninety-three [1993] was the first model year we ever built a model certified to seventy-five [1975] standards.”But it wasn’t just the Clean Air Act they battled – which they fought from its inception in 1970 through subsequent amendment and into the late 1990s when new “smog & soot” provisions were sought. They also won rollbacks on fuel economy standards, learned how to game fleet accounting under the CAFÉ (Corporate Average Fuel Economy) program, and also threatened to use “foreign content” or move plants abroad to skirt MPG goals. When California moved to encourage electric vehicle development with tighter emissions standards, they worked to scuttle that program. And when Northeast states sought to adopt tighter California emissions standards, they fought that as well. They sometimes used front groups and fake grass roots names to oppose new actions in Congress. And they spared no expense in lobbying and PR campaigns to oppose updates to the clean air and fuel economy laws.

David Halberstam’s 1986 book on Ford & Nissan provides period context & perceptive historical analysis. Click for copy.

And although American automakers had studied or knew about improvements such as front-wheel drive, fuel injection, improved transmissions, and multi-valve engines (some, as early as the 1950s, and again in the early 1970s) – all technologies that would improve fuel efficiency and more – they ignored them or were slow to install them, lagging behind their competitors by years in some cases.

When sales went flat on the heels of energy crises, they typically asked Congress for help and regulatory relief. In periods of high profits, they spent their proceeds poorly, some on mergers and acquisitions rather than improved engineering of cars and trucks.

When the “quality revolution” arrived to make them better competitors, environmental and energy elements were not incorporated into the capital goods calculus. All in all, there were missed opportunities in the 1950s-1990s time frame that could have made the outcomes much different.

Most puzzling to those who studied and knew the industry, including any number of engineers inside Detroit, was the fact that the industry clearly had the technical capability to be energy and environmental leaders. Afterall, this was the industry that became the “Arsenal of Democracy” in WWII, converting their plants overnight to turn out a staggering array of fighter planes, tanks, and technologically complex weapons and other munitions. In more recent years, they have helped NASA. So why the decades-long histrionics over energy and environmental improvements?To be sure, the air in America today is cleaner than it was in the 1950s and 1960s, as the energy and environmental performance of Detroit-made motor vehicles is much improved, no question. But as the annual reports of the American Lung Association typically show, there are too many metro areas in America (and around the world) having bad ozone days. And while “end-of-combustion-engine” deadlines and surging electric vehicle development now hold promise for further reducing the motor vehicle share of bad air and greenhouse gases, we are clearly not out of the woods yet.

Much more detail on the auto industry’s economic and environmental history is found in any number of the books and reports cited in this story and in the “Sources” section below. Additional stories at this website with auto industry content include the following: “The DeLorean Saga” (about John DeLorean’s rise and fall at GM and his bid to build the DeLorean Motor Car); “G.M. & Ralph Nader” (covering Nader’s book Unsafe at Any Speed and GM’s attempt to discredit him); and “Dinah Shore & Chevrolet” (about the popular 1950s TV personality who helped sell Chevrolets).

Thanks for visiting – and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research, writing and continued publication of this website. Thank you – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

____________________________________

Date Posted: 22 May 2021

Last Update: 22 May 2021

Comments to: jdoyle@pophistorydig.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Smog Conspiracy: DOJ vs. Detroit

Automakers,” PopHistoryDig.com, May 22, 2021.

____________________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

“City Hunting for Sources of ‘Gas Attack’,” Los Angeles Times, July 27, 1943.

E. Ainsworth, “Fight to Banish Smog, Bring Sun Back to City Pressed,” Los Angeles Times, October 13, 1946.

“Experts Full ‘Smog Report’ To Appear in Sunday Times,” Los Angles Times, January 17, 1947, p. 1.

“Air Pollution Experts to Confer Here 3 Days Starting Wednesday,” The Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), May 1, 1950.

“Air Pollution Calls for Local Laws, President Declares,” The Evening Star, May 3, 1950.

J.O. Payne & H.W. Sigworth, “The Composition and Nature of Blowby and Exhaust Gases. . . ,” Proceedings of National Air Pollution Symposium, 2nd symposium, Pasadena, CA, May 1952, pp. 62-70.

“Smog Perils Air Traffic in L.A. Area,” Daily News (Los Angeles), November 5, 1953, p. 1.

“Blight on the Land of Sunshine,” Life, November 1, 1954, pp. 17-19.

Edward D. Fales Jr., “His Smoke-Eating ’Cats’ Now Attack Traffic Smog” [re: catalytic converter research], Popular Science, June 1955.

Associated Press, “Los Angeles Gropes Way With Stinging Eyes in Worst Smog,” New York Times, September 14, 1955, p. 37.

L. Hitchcock, “Diagnosis and Prescription,” in Proceedings of Second Southern California Conference on Elimination of Air Pollution, November 14, 1956, pp.76-78.

U.S. Congress, “Unburned Hydrocarbons,” Hearing on H.R. 9368 [Schenck bill ]Before Special Subcommittee on Traffic Safety, Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce, U.S. House of Representatives, Eighty-fifth Congress, Second Session, March 17, 1958.

“City and County Join Forces to Seek Car Smog Controls,” Los Angeles Times, January 6, 1959, p. C-1.

“Supervisors Demand Auto Exhaust Law,” Los Angeles Times, October 24, 1959, p. 1.

U.S. House of Representatives, “Air Pollution Control Progress,” Hearings before the Subcommittee on Public Health and Welfare of the Interstate and Foreign Commerce Committee, February 23-24, 1960.

P. A. Bennett, R.V. Jackson, C.K. Murphy, and R. A. Randall, “Crankcase Gas Causes 40% of Auto Air Pollution,” SAE Journal of Automotive Engineering, March 1960.

Al Thrasher, “Brown Names State Smog Control Board,” Los Angeles Times, May 27, 1960, p. B-1.

Alexander B. Hammer, “California Smog Spurs a Big Rush,” New York Times, August 14, 1960, p. F-1.

Air Pollution Foundation, Final Report, Los Angeles, CA, 1961.

V. Jones, “Anti-Smog Device Uses Catalyst,” New York Times, June 30, 1962, p. 23.

“Air Standard Elusive for Car Smog Devices,” Los Angeles Times, 11 May 11, 1964, p. A-1.

S. Griswold, “Reflections and Projections on Controlling the Motor Vehicle,” Annual Meeting of the Air Pollution Control Association, Houston, Texas, June 25, 1964.

Ralph Nader, Chapter 4, “The Power To Pollute: The Smog That Wasn’t There,” Unsafe At Any Speed, New York: Grossman Publishers, 1965.

E. W. Beckman, W. S. Fagley, Jorma O. Sarto (Product Planning Staff, Chrysler Corp.), “Exhaust Emission Control by Chrysler – The Cleaner Air Package,” SAE Technical Paper 660107, 1966 Automotive Engineering Congress and Exposition, published, February 1, 1966.

Eileen Shanahan, “U.S. Charges Auto Makers in Plot to Delay Fume Curbs,” New York Times, January 11, 1969, p. 1

“Denials by Industry,” New York Times, January 11, 1969, p. 65.

Statement of Kenneth Hahn, County Board of Supervisors, Los Angeles County, Hearings Before a Special Subcommittee on Air and Water Pollution of the Committee on Public Works, U.S. Senate, 88th Congress, 2nd Session, “Field Hearings Held on Progress and Programs Relating to the Abatement of Air Pollution,” Los Angeles, California, January 27, 1964 (and five other cities).

“Smog-Control Unit Set for California In’66-Model Cars,” New York Times, August 13, 1964, p. 39.

U. S. Senate, Committee on Public Works, Letter of S. Smith Griswold to Edmund S. Muskie Regarding S. 306, April 16, 1965; “S. 306, Miscl. Corresp. Re air pollution” folder, Legislative Files, Box 3; Committee on Public Works; 89th Congress; Records of the U.S. Senate, RG 46; National Archives.

“Ecology: Menace in the Skies” (cover story on urban smog), Time, January 27, 1967.

“Smog Over Auto Accord. Car Makers Agreement To Pool Research and Data on Controlling Pollution Draws Justice Dept. Antiturst Suit…,” Business Week, January 18, 1969.

“GM Hints Auto Companies Seek to Settle U.S. Suit Over Air Pollution Control Units,” Wall Street Journal, February 12, 1969.

U.S. House of Representatives, Hon. George Brown, “Congressmen Urge Open Trial in Smog Control Antitrust Case,” Congressional Record, September 3, 1969, pp. H7441 – H7450.

“Settlement Is Proposed in Antitrust Suit Against Auto Makers Over Smog Devices,” Wall Street Journal, September 12, 1969.

“U.S. Settles Suit on Smog Devices,” New York Times, September 12, 1969, p. 1

Ralph Nader, Letter to Hon. Richard W. McLaren, Assistant Attorney General, Antitrust Division, U.S. Department of Justice, Washington, D.C., September 15, 1969.

“U.S. Dropping Pollution Suit in Pact with Automakers,” Detroit Free Press, September 12, 1969, p.12.

“Nader Hits Antismog Settlement,” Los Angeles Herald-Examiner, September 16, 1969.

Ray Zeman, “Release of Secret Smog Testimony to be Sought,” Los Angeles Times, September 25, 1969.

Steven V. Roberts, “Auto Plot on Coast Opposed; Out-of-Court Settlement Is Denounced as a ‘Sellout’,” New York Times, September 27, 1969, p.42.

“Brown Resolution Calls for Stronger Action in Smog Conspiracy Case,” Hon. George E. Brown, Jr., Congressional Record, extensions of remarks, October 6, 1969, pp. E-8195-96.

“City Asks Court to Force U.S. to Disclose Facts in Auto Plot,” New York Times, October 8, 1969, p. 30.

Gladwin Hill, “Decree Settles Auto Smog Suit; Court Backs the Government on Antipollution Measure,” New York Times, October 29, 1969, p. 28.

“Smog At the Bar,” Newsweek, November 10, 1969, p. 67.

“Automakers Sued By State for ‘Plot’ in Pollution Control,” New York Times, November 19, 1969.

“City Seeks Release of Evidence Linking Car Makers to Pollution,” New York Times, January 27, 1970.

John C. Esposito, Vanishing Air, the Ralph Nader Study Group Report on Air Pollution, Grossman: New York, 1970 (Chapters 2 and 3, respectively, “Twenty Years in Low Gear,” and “Nothing New Under The Hood”).

“15 States File Pollution Suit – Action in Supreme Court Asks Automakers Insert Control Devices,” New York Law Journal, August 6, 1970.

Office of Technical Information and Publications, Air Pollution Technical Information Center, U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Public Health Service, Environmental Health Service, National Air Pollution Control Administration, Hydrocarbons and Air Pollution; An Annotated Bibliography, Raleigh, N.C., October 1970.

Frank V. Fowlkes, “GM Gets Little Mileage From Compact, Low-Powered Lobby,” National Journal, November 14, 1970, p. 2502.

“New: A Catalytic Converter That Really Cleans Up Auto Exhaust,” Popular Science, December 1970.

Roger Turner, “Smith Griswold Sells the War Against Smog,” ScienceHistory.org, October 1, 2019.

Associated Press, “S. Smith Griswold Dead at 62; Early Fighter Against Pollution,” New York Times, April 22, 1971.

Hon. Phil Burton, “Smog Control Antitrust Case,” Congressional Record, May 18, 1971, pp. H 4063-4074.

Morton Mintz, “Justice Dept. Had ’68 Memo On Auto Plot,” Washington Post, May 19, 1971, p. A-2.

John Lanan, “Probe Is Asked of Auto Makers Pollution `Plot,'” Washington Star, May 19, 1971, p. A-9.

Morton Mintz (LA Times-Washington Post Service), “Auto Makers Faced Criminal Suit on Smog,” The Detroit News, May 19, 1971, p. 4-C.

“Chrysler Defends Role in Reducing Auto Pollution,” Washington Post, May 21, 1971, p. A-3.

“Inquiry on Auto Industry Urged in Anti-Smog Delay,” New York Times, May 19, 1971, p. 93.

Memorandum of the U.S. Justice Department, Antitrust Division, citing rough draft of paper presented at ECS-APCA Meeting, by James M. Chandler, Chairman, VCP-AMA, entitled, “Current Status and Future Work on Vehicle Emissions Control Devices,” grand jury exhibit 381.

“Detroit Promises Clean-Air ’75s…But Ups the Sticker Another $300,” Popular Mechanics, September 1973.

Kenneth F. Hahn, Smog: A Factual Record of Correspondence Between Kenneth Hahn and Automobile Companies, Los Angeles, 1970.

Editorial, “How Clean A Car and How Soon,” Life, March 26, 1971, p. 32.

Senator Ed Muskie, “Clean Air,” Letter to the Editor, Life, May 7, 1971, p. 25.

Associated Press, “Auto Makers Win Ruling on Pollution,” New York Times, Nov. 27, 1973.

Agis Salpukas, “Los Angeles Officials Insist the Air is Getting Cleaner,” New York Times, August 7, 1972.

Bennett H. Goldstein and Howell H. Howard, “Antitrust Law and the Control of Auto Pollution: Rethinking the Alliance Between Competition and Technical Progress,” Environmental Law, Vol. 10, No. 3 (Spring 1980), pp. 517-558.

“Energy: Detroit’s Most Difficult Deadline,” Time, December 31, 1973.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, “A Review and Analysis of The Good Faith of The Automobile Industry in Attempting to Comply with The Statutory 0.4 NOx Standard,” A Report to the Senate Public Works Committee, U.S. Congress, 1975, 120 pp.

Michael Weisskopf, “Auto-Pollution Debate Has Ring of the Past,” Washington Post, March 26, 1990.

Scott H. Dewey, “The Antitrust Case of the Century”: Kenneth F. Hahn and the Fight Against Smog, Southern California Quarterly, Vol. 81, No. 3 (Fall 1999), pp. 341-376.

U.S. Congress, “Unnecessary Business Subsidies,” Hearing Before the Committee on the Budget, House of Representatives, 106th Congress, 1st Session, Washington, D.C., June 30, 1999· Volume 4.

Martin V. Melosi, “Auto Emissions and Air Pollution,” The Automobile and the Environment in American History, University of Michigan Series, Automobile in American Life and Society.

Tim Palucka, “Doing The Impossible: When Congress Mandated a 90 Percent Cut in Auto Emissions, Almost No One Thought it Could Be Achieved. The Inventors of the Catalytic Converter Proved Otherwise,” Invention AndTech.com, Winter 2004, Vol. 19, Issue 3.

Harry Stoffer, “GM Fought Safety, Emissions Rules, but Then Invented Ways to Comply,” AutoNews.com, September 14, 2008.

David Traver Adolphus, “1960: The Smog War Begins,” Hemmings.com, August 12, 2010.

Jim Motavalli, “Crying Wolf: 5 Automaker Excuses for Avoiding Innovation,” CBSnews .com, May 17, 2011.

Douglas S. Eisinger, Smog Check: Science, Federalism, and the Politics of Clean Air, 2012.

“Smog Galore! The 10 Most Polluted Cities in America,” Parade, May 1, 2014.

Lauren Raab, “How Bad Was L.A.’s Smog When Barack Obama Went to College Here?,” Los Angles Times, August 3, 2015.

Sam Kean, “The Flavor of Smog. In the 1940s Two Chemists Joined Forces to Fight Los Angeles’s Stinky, Stinging Air,” ScienceHistory.org, October 15, 2016.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, “Timeline of Major Accomplishments in Transportation, Air Pollution, and Climate Change,” EPA.gov, January 2017.

John Bachmann, David Calkins, Margo Oge, “Cleaning the Air We Breathe: A Half Century of Progress,” EPA Alumni Association, September 2017.

William K. Reilly and Kenneth Kimmell, Op-Ed, “Automakers Shouldn’t Fight Emissions Standards,” New York Times, October 19, 2017.

Dave Cooke, “Automakers’ Long List of Fights Against Progress, and Why We Must Demand Better,” Blog.USCusa.org (Union of Concerned Scientists), December 6, 2017.

Rian Dundon, “Photos: L.A.’s Mid-Century Smog Was So Bad, People Thought it Was a Gas Attack,” Timeline.com, May 23, 2018.

Tony Barboza, “Must Reads: 87 Days of Smog: Southern California Just Saw its Longest Streak of Bad Air in Decades,” Los Angles Times, September 21, 2018.

Amanda Grennell, “The Decades-Long War on Smog; What History Tells Us About Addressing Today’s Pressing Air Pollution Problems,” ScientificAmerican.com, April 16, 2019.

James Pasley, “35 Vintage Photos Reveal What Los Angeles Looked like Before the U.S, Regulated Pollution,” Insider.com, January 7, 2020.

Daniel Stern, “Automotive History: The Dawn of the Catalytic Converter – Who Put the Cat Out?,” CurbsideClassic.com, February 3, 2020.

Coral Davenport, “U.S. to Announce Rollback of Auto Pollution Rules, a Key Effort to Fight Climate Change,” New York Times, March 30, 2020.

Aaron Robinson, “Fifty Years Ago, the Government Decided to Clean up Car Exhaust. It’s Still at It,” Hagerty.com, October 7, 2020.

Dale Kasler, “California’s Long Game of Tug-of-War With the Auto Industry; California Has Banned the Sale of Gasoline-Powered Cars by 2035 and Automakers Retort with Concern about the State’s Electric Grid and Consumer Preference for Gas Vehicles. This Back and Forth Is Decades Long,” The Sacramento Bee / Governing.com, October 8, 2020.

____________________________