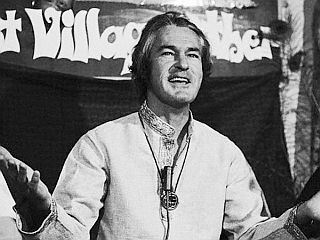

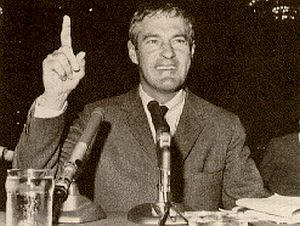

Timothy Leary during a press conference in New York City, September 19, 1966 – “turn on, tune in, drop out.”

LSD, also known in the 1960s by its slang name, “acid,” became something of a revolutionary, counter-cultural substance in that period. And Leary, after a time as a university researcher exploring the drug’s psychotherapy potential, became a kind of “pied piper” for the drug’s recreational and spiritual use. He would write a dozen or more books on LSD and the psychedelic experience. And with subsequent media attention, he became something of national guru to a younger generation then rebelling against the status quo. During the 1960s he also became known for his phrase, “turn on, tune in, drop out,” a slogan he used for urging people to embrace self-enlightenment through psychedelic drugs and mind expansion, while “dropping out” – i.e., breaking free of social convention, questioning authority, and becoming independent thinkers. Leary’s explanation of his slogan was typically more nuanced than what the media often suggested, i.e, “getting stoned; dropping out of school, work, etc.”

What follows below is a short history on Leary and the times – from his Harvard days and LSD proselytizing to his run-ins with famous entertainer Art Linkletter, U.S. President Richard Nixon, and the federal government in their denunciations of him and their battles over drug use, as well as Leary’s flight from the law. But first, by way of musical introduction to show how Leary imprinted on popular culture of that day is the history of the Moody Blues hit song of 1968, “Legend of A Mind,” which served to boost the respective careers of Leary and the Moody Blues as well as burnishing the Leary/LSD connection in cultural history.

“Legend of a Mind” was recorded by the Moody Blues in January 1968 and was first released in July 1968 on their album, In Search of the Lost Chord, which explores a variety of “quest and discovery” themes, including those of spiritual development and higher consciousness. The U.S. drug scene had already begun to surface in 1965-66, and Leary and LSD had both been in the popular press by then as well. “Legend of A Mind” is seemingly a praiseworthy ode to Leary, intimating for him a guru-like status, though it is the song’s Eastern mystical sound that conjures up a trip-like, ethereal quality, offering a prime example of that era’s psychedelic music.

Music Player

“Legend of a Mind”

MoodyBlues-1968

Known for an earlier 1964 rock-n-roll hit, “Go Now,” the Moody Blues had gone through some personnel changes by 1967-68 and began moving in a new musical direction. The group then consisted of Justin Hayward, vocals and guitar; John Lodge, bass, guitar, vocals; Ray Thomas, flute, percussion, harmonica, vocals; Mike Pinder, keyboards, vocals; and Graeme Edge, drums, percussion, vocals. The group’s previous album, Days of Future Passed, of 1967, produced hit songs such as “Nights in White Satin” and “Tuesday Afternoon,” marking them as a rising international rock band.

The Moodies’ style and sound at this point in their career had a certain orchestral, Eastern, and mystical quality about it, due in part to the use of a novel keyboard instrument called a Mellotron – an instrument capable of duplicating orchestral sounds of violins, flutes, choirs, and more. Adding to the Moodies’ distinctive sound at this time were two Indian instruments – the sitar and the tambura – then being used selectively by other groups such as the Rolling Stones and the Beatles as well. The sitar and tambura are heard throughout In Search of the Lost Chord and “Legend of a Mind.”

Ray Thomas, who wrote the song, sings the vocals, and also has a long, beautiful flute interlude in the middle of the 6:40 minute song. That portion of the song suggests an under-the-influence moment, as wandering, seductive background music ebbs and flows, finally emerging with an optimistic ending and presumably, a positive “trip around the bay.”

|

“Legend of a Mind” Timothy Leary’s dead. Timothy Leary’s dead. Along the coast you’ll hear them boast He’ll take you up, he’ll bring you down, He’ll take you up, he’ll bring you down, He’ll fly his astral plane. |

The Moody Blues song, while never mentioning LSD per se, puts Leary at the center of its lyrics, describing him as the person who dispenses thrills on “trips around the bay.” But more than the lyrics, it is the song’s musical sound that suggests the mystical and “trippy” effects of LSD. In fact, the Moodies’ music captured the psychedelic experience perhaps as good, if not better than, any group of that era.

Bruce Eder of AllMusic.com, writing a profile of Ray Thomas, observes:

…Thomas delivered the [MoodyBlues’] defining psychedelic-era anthem, “Legend of a Mind.” With the central phrase “Timothy Leary’s dead/Oh no, he’s outside, looking in” and its elaborate instrumentation (swooping cellos and droning Mellotron sharing the spotlight with Thomas’ flute), the song became a central part of the psychedelic era’s ambience, and part of the pop culture ‘soundtrack’ almost as much as the Beatles’ ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’ or ‘Penny Lane;’ the fact that it utilized the name of Dr. Timothy Leary, a widely known, once respected academic turned LSD guru, only boosted the group’s credibility as a serious psychedelic act within the counterculture of the period….

1967-1968

In 1967, the “Summer of Love” commenced with all manner of young people gathering in San Francisco, elevating the term “hippie” in popular culture as well as the Haight-Ashbury drug scene.

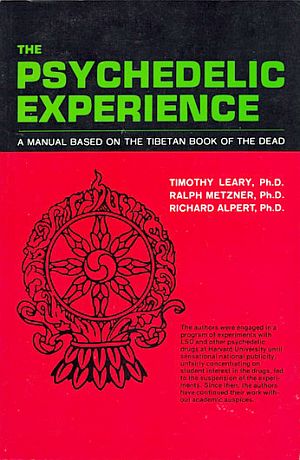

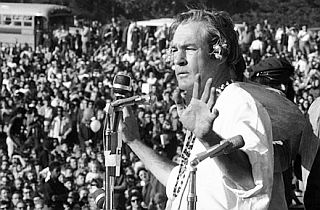

Timothy Leary was already some years into his LSD notoriety by then, having published The Psychedelic Experience in 1964 with colleagues Richard Alpert and Ralph Metzner and lectured around the country. In San Francisco in 1967, Leary spoke at the “Human Be-In” gathering in January at Golden Gate Park (more on this later) where some 30,000 heard him offer his philosophical phrase, “turn on, tune in, drop out.”

The following summer, the Moody Blues released In Search of the Lost Chord, hitting No. 23 on the U.S. album charts in July 1968, also reaching No. 5 in the U.K. Three songs from the album would bring more notice to the Moodies – “Ride My See-Saw,” “Voices in the Sky,” and “Legend of a Mind.” And the album itself would be lauded over the years for its musicianship (33 instruments used by the Moodies themselves) and its mystical and psychedelic qualities.

“In Search of The Lost Chord” album artwork and theme played into the Eastern mysticism and psychedelic strains of its songs. Click for album.

Socio-Political Milieu

The 1960s, meanwhile, continued to see cultural change throughout the world, driven by the post-WWII baby boom. By 1968 in America – a presidential election year – political tumult and convulsive change were front and center. Already buffeted by ongoing Vietnam War protests and civil rights unrest, the assassinations of Martin Luther King in April and Bobby Kennedy in June added more woe to the nation’s misery. Then came the televised protests and street riots at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago that August. Social protest, drugs, alternative life styles, Eastern mysticism, and the call of the counterculture were all part of the scene. Youth the world over were then searching for explanations and alternatives. The “Timothy Leary” song became part of the musical backdrop.

Although Leary initially did not like the Moody Blues song, he soon adopted it as something of a theme song during his lecture tours. But the irony was, as Ray Thomas would later reveal in a Rolling Stone interview, he wrote the song as something of a put on; “I was taking the piss out of him,” Thomas said in the interview. “I saw the ‘astral plane’ as some gaily painted little biplane: you pay your two bucks, and he’ll take you around the bay for a little flight…” Numerous listeners, however, never got the put on, “hearing” the song’s spiritual and exploratory content instead.

Moody Blues band member Ray Thomas, author of “Legend of a Mind,” during flute solo in later years.

“Some of us in the band — and this was 1966, ’67 — were going through our own psychic experiences, as a lot of musicians were at the time, probably being led by the Beatles. We were reading a lot of underground press and reading about Tim Leary, so we put him in…”

“The song is a very tongue-in-cheek version, a very cheeky English version of what we thought things would be like in San Francisco in the `flower power’ days’… It was tongue in cheek, but with a background of serious meaning. It did mean something to us. We were using a lot of phrases of the time, extracts from the Tibetan Book of the Dead, talking about the astral plane and so forth, and it’s a reflection of that.”

The classic guide to Tibetan traditions and thought, seen in the 1960s as a basic text for psychedelic explorations. Click for copy.

Moody Blues keyboardist Mike Pinder, who arranged the song, said in a 1996 interview, that the line,“Timothy Leary’s dead / Oh, no, he’s outside looking in,” was actually a high compliment to Leary. “It was quite metaphysical,” Pinder explained. “It used him as an out of body experience and looking back at life at a normal level.”

Others have also noted this line in a similar vein, that “Timothy Leary’s dead” had to do with “ego death” as experienced in transcendental meditations as instructed in Tibetan Book of the Dead. In fact, Leary’s 1964 book, written with colleagues Richard Alpert and Ralph Metzner – The Psychedelic Experience – also instructed its readers how to prepare for and take LSD and other such drugs and was subtitled, A Manual Based on the Tibetan Book of The Dead.

“Those who didn’t get the message behind the song,” Pinder would say with a laugh during his 1996 interview, “were on the other outside looking in.” As for Leary, he never had a problem with the song, according to Pinder.

1968: The Moody Blues, as seen on the cover sleeve of one of their singles, "Ride My See-Saw." Click for digital version.

“Legend of A Mind” certainly made Leary more of a pop star than he already was at the time, and kept his name tied to that era thereafter.

For the Moody Blues, “Legend of a Mind,” proved to be one of their most popular numbers, especially in concerts stretching over some 35 years.

And apart from the song’s composition and history, there is, of course, a lot more to the legend of Timothy Leary and LSD than the Moody Blues tune. That part of the story is next.

_________________________________

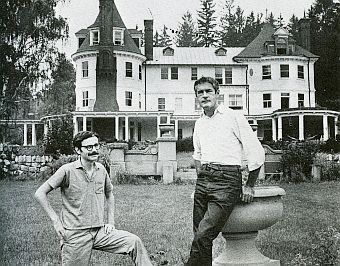

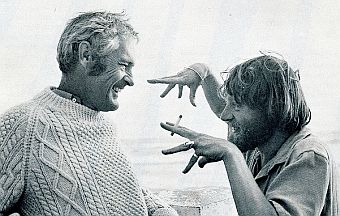

1961: From left, Dr. Timothy Leary and Dr. Richard Alpert at Harvard University.

Timothy Leary

Dr. Timothy Francis Leary (1920 –1996) was born in Springfield, Massachusetts, the only child of an Irish Catholic family. His parents separated when Leary was 13 – his father, a dentist, left his mother. Leary graduated high school in Springfield, but his college experience would be protracted and difficult. He passed through several colleges – Holy Cross, West Point, and the University of Alabama – running afoul of rules and regulations, ranging from alleged honor code violations at West Point to expulsion from the University of Alabama for an overnight stay in a women’s dorm. Later reinstated at Alabama after service in the Army during WWII, Leary received his undergraduate degree in psychology in 1943. By 1946 he received an M.S. in psychology at Washington State University and in 1950, a Ph.D. in clinical psychology at the University of California, Berkeley. Leary then became an assistant professor at Berkeley. Through 1958, he was also director of psychiatric research at the Kaiser Family Foundation Hospital in nearby Oakland. During these years, he was discovering that conventional psychotherapy was not exactly his cup of tea. But in his Berkeley years, he and his wife were party goers, drinkers, and had their respective affairs. In 1955, his wife committed suicide, leaving him to raise two young children. On a sojourn to Europe, he met David McClelland, director of the Center for Personality Research at Harvard University, who found Leary’s work impressive, offering him a position at Harvard. In 1959, joined McClelland’s research center at Harvard and also became a university lecturer in psychology.

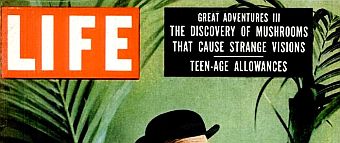

Cover headline for May 13th, 1957 edition of Life magazine story reporting on “mushrooms that cause strange visions” in Mexico.

Front cover of The Harvard Review’s “Drugs and the Mind,” special edition, Summer 1963. Click for copy.

Leary and his colleagues also caught the attention of other academics with their writing in The Harvard Review, which published a special edition in the summer of 1963 on “Drugs and The Mind.” Leary and Richard Alpert published the lead article, “The Politics of Consciousness Expansion.” And coming from two respected Harvard scholars at the time, it created quite a stir – in fact, the whole edition did. And there was more on the way, as the back cover advertised a new forthcoming journal — The Psychedelic Review, edited by Leary and Alpert associate, Ralph Metzer – which became a serious academic journal and was published through 1971. But it was the lead article by Leary and Alpert in The Harvard Review that got the attention of East Coast intellectuals, and was a sign of things to come in the 1960s. According to the website Lysergia.com, “The Politics of Consciousness Expansion” by Alpert and Leary, “represents the exact point where Leary, Alpert and their merry band of acidheads started to diverge from the straight academic path.”

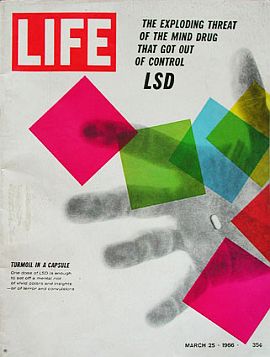

Yet well before Leary’s involvement, LSD was a reputable research field, with lots of earnest scientists looking into possible uses and effects. By one count, between 1949 and 1959 there were nearly a thousand published papers on LSD in professional journals. There were also a few reports that had appeared in the mainstream press.

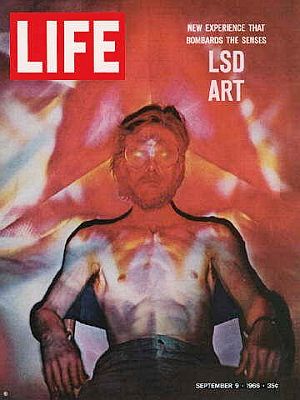

Time-Life publications – owned by Henry and Clare Boothe Luce, who had both indulged in LSD – were said to have given favorable coverage to LSD early on, here for the Sept 9, 1966 cover story featuring “LSD Art.” Click for copy.

“Time and Life were fascinated by LSD,” wrote Stephen Siff’ in a 2008 paper for Journalism History. “Henry Luce’s magazines discovered LSD in 1954 and remained enthusiastic even as the drug was becoming popular with recreational users, frequently discussing the experience in an explicitly biblical framework. Scare stories were balanced with endorsements of LSD by professors, businessmen, and celebrities, and some articles even read like advertisements…” Time first wrote about LSD in 1954 with an article titled, “Dream Stuff,” an account of LSD’s use in psychotherapy. “LSD 25, while it has no direct curative powers, can be of great benefit to mental patients,” the magazine stated. Life magazine, in “Seeking the Magic Mushroom” of May 13, 1957 (top of cover shown above earlier), documented the use of psilocybin mushrooms in the religious ceremony of the indigenous Mazatec people of Mexico. And Time in 1960 reported on celebrities taking LSD under the supervision of their doctors. Years earlier in Switzerland, meanwhile, a research chemist named Albert Hofmann working at Sandoz Pharmaceuticals had synthesized both LSD and psilocybin, which were made readily available to U.S. and other researchers by 1949.

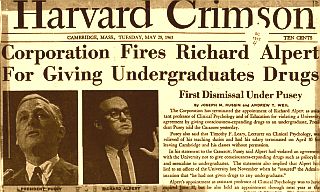

May 1963: Harvard University’s newspaper, “The Harvard Crimson,” reports the firing of Richard Alpert, a story soon picked up by other news outlets nationally.

Early 1960s: Ralph Metzner (left) and Timothy Leary (right) in front of the Millbrook estate. Photo, New York Daily News.

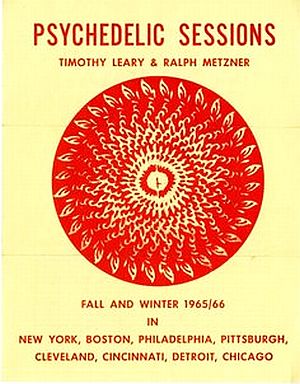

1965-66: Poster for “Psychedelic Sessions” by Leary & Metzner in various U.S. cities. |

In August 1964, Leary, Ralph Metzner and Richard Alpert published, The Psychedelic Experience: A Manual Based on The Tibetan Book of the Dead, in part, a “how to” guide intended for those planning to use psychedelic drugs. The book rose to bestseller status by 1966. A reading from the book was also recorded by the authors as a spoken-word LP under the name The Psychedelic Experience in 1966 . Leary also recorded another spoken-word album, titled LSD (cover shown later below), which instructed on the use of the drug and answered questions about its effects. Leary and Alpert would also hold meetings with the press when traveling in various U.S. cities. In December 1964 Leary and fashion model Nena von Schlebrugge were married at the Millbrook estate, though divorced not long thereafter.

It was in 1966 that Leary began using his slogan, “Turn on, tune in, and drop out” – inspired in part by Marshall McLuhan, the famous mass media analyst and advertising man. McLuhan coined the phrase “the medium is the message” in his famous 1964 book, Understanding Media. McLuhan and Leary had lunch in New York City sometime in 1966 — a meeting recounted by Leary, during which McLuhan offered other advice to Leary, suggesting the key to Leary’s work was advertising and that his product – “the new and improved accelerated brain” – should be promoted to arouse consumer interest.

“Associate LSD with all the good things that the brain can produce—beauty, fun, philosophic wonder, religious revelation, increased intelligence, mystical romance,” McLuhan reportedly told him. “…[G]et your rock and roll friends to write jingles about the brain.” He also gave Leary some style pointers – again, according to Leary’s account: “Wave reassuringly. Radiate courage. Never complain or appear angry. It’s okay if you come off as flamboyant and eccentric. You’re a professor, after all. But a confident attitude is the best advertisement. You must be known for your smile” – all advice Leary appears to have adopted.

In 1966 Leary testified before a U.S. Senate hearing in support of citizen’s right to experiment with consciousness raising drugs. But by the mid-1960s, Leary had run afoul of the law on some drug charges. In fact there would be three arrests over a period of several years: one at the Mexico border in Laredo, Texas in 1965; another at the Millbrook Estate in 1966; and the last in Laguna Beach, California in 1968. Convicted for illegal possession of marijuana on the Texas charge, Leary’s conviction under appeal was reversed by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1969. The Millbrook arrest yielded no drug charges. The Laguna Beach arrest for possession of marijuana, however, would result in a conviction and prison term. More on this a bit later.

1966: Timothy Leary’s “spoken word” LP on LSD.

In one of the Life pieces, the views of a cross-section of individuals were presented, including that of a Navy intelligence analyst who took the drug to help solve a problem in pattern recognition while developing intelligence equipment. A theologian who took LSD reported a “Moses-like burning bush” revelation, feeling his was a positive experience.

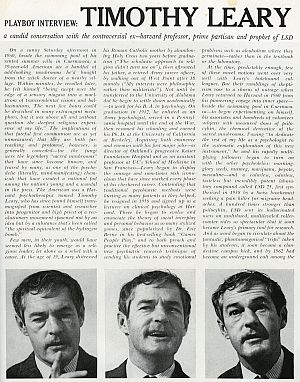

Sept 1966: First page of Timothy Leary’s interview with Playboy magazine, then a popular outlet for new ideas.

The Life editors also offered a question-and-answer series on LSD aimed at the general public, which prompted Leary and friends to put out their own spoken-word recording – an “LSD” LP on Capitol records – that addressed many of those same questions (see image above).

In September 1966, Leary also had a featured interview with Playboy magazine, then well known and well regarded for it lengthy interviews with leading personalities of the day.

But the rising “street use” of LSD soon raised social concerns, which would lead to restrictions and controls on the substance. Sandoz tightened researchers’ access to the drug in 1963 and again 1966 amid concerns about the volume of LSD leaking out of laboratories and into the hands of recreational users. Then, in 1965, the U.S. Congress passed legislation prohibiting the sale of LSD, but not possession for personal use.

Other bills in Congress proposed to ban the substance completely. Senator Thomas Dodd (D-CT), one of those moving in that direction, convened subcommittee hearings in late May 1966 on recreational drug use among America’s youth. Timothy Leary was one of the witnesses Dodd called to testify. In his testimony, Leary asserted: “the challenge of the psychedelic chemicals is not just how to control them, but how to use them.” He emphasized the need for further investigation of LSD rather than prohibition. He claimed that LSD and many other psychedelic drugs were not dangerous, so long as they were used wisely and with precautions. Senator Dodd, however, pointed to earlier testimony by a doctor who said LSD encouraged homicidal tendencies and destructive behavior.

Timothy Leary giving Senate testimony, 1966.

In 1966, New York passed an anti-LSD law and California followed suit later that year, in October. Still, the drug culture – and LSD usage – were at its peak, and no where was this more apparent than San Francisco.

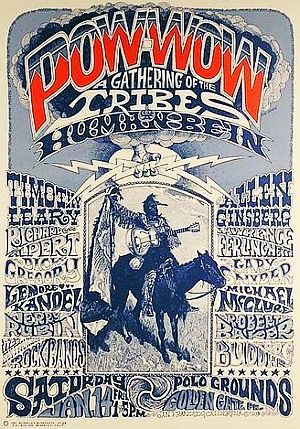

One version of poster advertising the Jan 14, 1966 “Human Be-In” in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park.

San Francisco

By 1966-1967, the counter culture was becoming a growing movement in America, especially on the West Coast, and San Francisco had become one of its epi-centers. An eclectic assortment of disaffected youth, activists, “Hippies,” “flower children,” and others were coming to the city. Many of those who came were suspicious of government, opposed the Vietnam War, and rejected consumerism. Others pursued communal living. Still others were on a spiritual quest, involved with transcendental meditation.

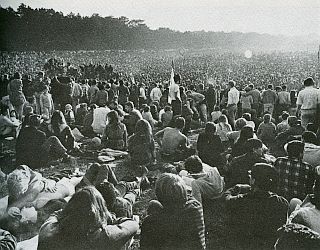

In January, a huge turnout of some 25,000 to 30,000 people of all stripes came to the Polo Grounds area of San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park for what had been billed and promoted in the alternative press as a “Pow-Wow” and “a gathering of the tribes” in the Bay Area – a coming together for a “Human Be-In.”

The gathering was also conceived locally as something of a unity rally, as there were philosophical differences among various factions, especially between those who thought the movement should be more political and more activist, as opposed to those who thought it should be more spiritual, inner-directed, and a-political, not involved with trying to change the system. Leary would become a figurehead for this latter group, generally the hippie/spiritual contingent.

January 14th, 1967: Some 25,000 to 30,000 came to Golden Gate Park in San Francisco for “Human Be-In” gathering. |

Timothy Leary addressing the assembled thousands at Golden Gate Park, San Francisco, January 14th 1967. |

Leary, in fact, was prominent among the headliners that day – those featured in the program of speakers and music that Saturday January 14th. Among others were Richard Alpert, Allen Ginsberg, Jerry Rubin and others. A host of local rock bands were also on hand, among them, the Grateful Dead, Quicksilver Messenger Service, Santana, and the Steve Miller Band. LSD flowed freely throughout the crowd, as the “Be-In” was also, in part, a protest against California’s law enacted in October 1966, banning the use of LSD.

Leary, in his all-white garb that day – dress that would become part of his persona at such events – appeared with flowers tucked behind his ears and offered his message of “tune in, turn on, drop out” to the crowd. At the time he was 45?? years old. Still he became something of figurehead for the new movement.

In many ways, the January 1967 “Be-In” was a warm-up for the “Summer of Love” that followed in San Francisco that same year, popularized by the song, “San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair),” written by John Phillips of The Mamas & the Papas, and sung by Scott McKenzie. The song, released in May 1967, was also used to promote the Monterey International Pop Music Festival, another big youth and counterculture event held in June of that year. College and high-school students began streaming into the Haight-Asbury section of San Francisco during the spring break of 1967 – a pilgrimage that continued through the summer, swelling the city’s population by an additional 100,000 or so newcomers. At the Monterey Festival that summer, a classic line-up of 1960s artists performed, including the Grateful Dead, the Animals, Simon and Garfunkel, Jefferson Airplane, The Mamas & the Papas, The Who, Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin. Also that June, the Beatles released their Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, which became part of the “summer of love” soundtrack.

Cover art for soundtrack album used with Timothy Leary’s film, “Turn On, Tune In, Drop Out.”

But Leary also wanted to make a film using his play as a starting point, and he reportedly sold the rights to Death of Mind to Columbia Pictures, receiving a down payment of $300,000.

In May 1967, a 35mm film starring Leary, Alpert and Leary’s partner, Rosemary, came out in Los Angeles. The film used the title, Turn On, Tune In, Drop Out. It also had its own musical score recorded by Mercury Records, also titled Turn On, Tune In Drop Out: The Original Motion Picture Soundtrack. The film, however, went nowhere, and had a very limited showing.

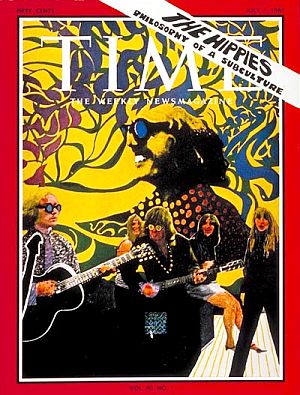

July 1967: Time magazine featured the cover story, “The Hippies: Philosophy of a Subculture.”

By then, a debate over the meaning of the counterculture and the drug scene had already begun. And in the Time magazine piece, everyone from historian Arnold Toynbee to California’s Bishop James Pike offered their views. Worried parents were represented as well, troubled over their children dropping out of college.

The article also described the guidelines of the hippie code – which sounded a lot like Timothy Leary’s slogan: “Do your own thing, wherever you have to do it and whenever you want. Drop out. Leave society as you have known it. Leave it utterly. Blow the mind of every straight person you can reach. Turn them on, if not to drugs, then to beauty, love, honesty, fun.”

Psychedelia, in any case, was in full flower by that time, receiving mass media attention. And Timothy Leary was often part of the story.

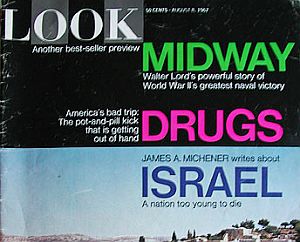

August 8th, 1967, Look magazine: “America’s Bad Trip: The Pot-And-Pill Kick That Is Getting Out of Hand.”

“America’s Bad Trip”

By August 1967, American press reports were turning more skeptical and negative on the drug scene. One of the stories receiving headline treatment on the cover of the August 8th, 1967 edition of Look magazine used the tagline “Drugs: America’s Bad Trip: The Pot-and-Pill Kick That’s Getting Out of Hand.” But even in that issue, Timothy Leary was still getting a share of the coverage. He was profiled and interviewed by Look senior editor J.M. Flager who visited Leary at the Millbrook estate in New York. The five-page spread on Leary also included photos by James H. Karales, and was titled: “Drugs and Mysticism: The Visions of ‘Saint Tim’.” Amid photos of a Leary-staged play adapted in part from Herman Hesse’s Steppenwolf, and some room-to-room visits looking in on Millbrook residents, a few in meditative pose, Look offered a couple of bolded pull quotes on Leary and his activities. One that read: “Prophet or phony? An exotic scholar makes a religion of LSD,” and another on Millwood: “At Leary’s rustic mecca ‘every room is a psychedelic trip’.”

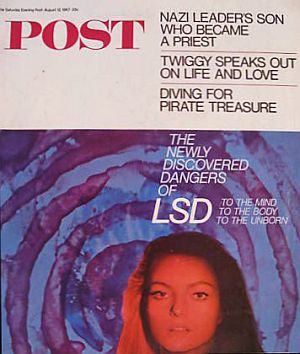

Sept 1967: The Saturday Evening Post cover story, “The Newly Discovered Dangers of LSD...” Click for similar issue.

The Saturday Evening Post also featured LSD on its cover in September 1967, also raising concerns with its tagline: “The Newly Discovered Dangers of LSD – To The Mind, To The Body, To the Unborn.”

The hippie and drug scene by then had fully permeated mainstream culture. In New York, the rock musical Hair, which told the story of the hippie counterculture and sexual revolution of the 1960s, opened off-Broadway on October 17, 1967.

In November 1967, Leary married his third wife, Rosemary Woodruff, a former actress and airline stewardess. Their wedding ceremony was held at a desert ranch house near Joshua National Monument in California. Many of the guests at the wedding were reportedly on acid at the time. By 1968, Leary and his family had moved from Millbrook, New York to Laguna Beach, California. From his new base he continued to write and lecture about the psychedelic experience.

In 1968, Leary published two more books – High Priest, a recounting of Leary’s 16 most life changing “trips” when under various forms of hallucinogens, and The Politics of Ecstasy, a collection of some of Leary’s essays and lectures the on the psychedelic drug experience – most previously published in magazines, journals and underground newspapers.

During 1968, Leary continued to crop up in news reports. One TV news clip from CBS-KPIX Channel 5 in San Francisco on July 10th, 1968 captured Leary’s remarks at a press conference at the Psychedelic Shop on Haight Street in San Francisco, where he offered his views about LSD, teenagers, and their parents. “LSD is not dangerous physically,” he told a reporter. “It can be dangerous psychologically to someone who’s not prepared to confront the energy and the grandeur and the wisdom of the divine process. It scares you out of your mind.” Further on in the interview, he praised a group of young people at the conference, and urged parents to try to understand why their kids were taking drugs and to learn what they were experiencing. He even suggested to parents: “Perhaps eventually, when you’re spiritually ready, you’ll turn on with your children.” It was also in July 1968 that the Moody Blues song about Leary, “Legend of Mind,” featured earlier above, was released on their album, In Search of the Lost Chord.

June 1969: Rosemary & Timothy Leary, Yoko Ono, and John Lennon, reading newspaper story about their “Bed-In” peace demonstration. Photo, Stephen Sammons

In Washington, DC, meanwhile, Richard Nixon had been elected president following a tumultuous year of political and social unrest, including the assassinations of Martin Luther Kind and Robert F. Kennedy. Through 1969, the Nixon Administration had begun to set a new tone across the nation.

Linkletter v. Leary

Art Linkletter, TV personality, began and anti-drug campaign after his daughter committed suicide in 1968.

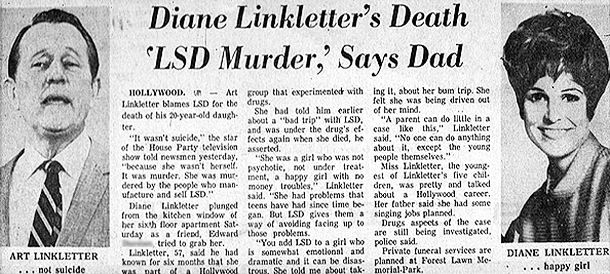

Also with Nixon that day at the Governors Conference was Art Linkletter – a popular TV personality known throughout the nation for his “Kids Say The Darndest Things” segment on his House Party TV show. Linkletter was one of the featured speakers to address the governors. The drug problem had hit Linkletter personally. His 20-year-old daughter, Diane, had committed suicide only months before, jumping to her death from the sixth floor of her West Hollywood, Calif., apartment on October 4, 1969. Linkletter blamed LSD as the culprit. “It isn’t suicide because she wasn’t herself,” Linkletter told the media shortly after he death. “It was murder. She was murdered by the people who manufacture and sell LSD.” Linkletter claimed that his daughter had taken LSD the night before her death, and her panic over its effects led to the fatal plunge. But an autopsy showed no trace of LSD in Diane’s body. However, Diane had taken acid six months before her death and Linkletter said she had experienced a “flashback,” which prompted her to jump out the window, an account which spread though the media.

October 1969: Associated Press news story reported shortly after the suicide death of Diane Linkletter, the 20-year old daughter of TV personality Art Linkletter, who maintained at this reporting, that LSD was the culprit in her death.

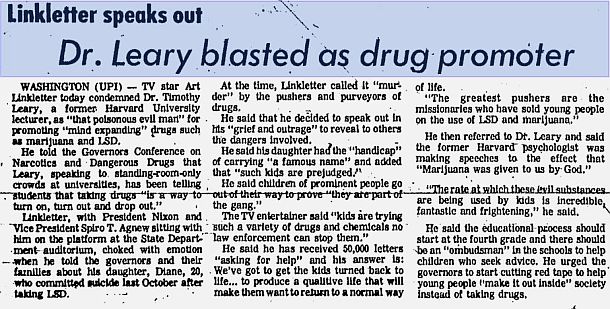

Two weeks after his daughter’s death, Linkletter was in the Cabinet Room of the White House, where President Nixon invited him to recount the tragedy to a small group of congressional leaders, including Senate Majority Leader Mike Mansfield, Speaker of the House John McCormick, and several others. At the December 1969 governor’s conference, meanwhile, with Nixon and Vice President Spiro Agnew on the platform, Linkletter told the governors that the older generation must help get kids “turned on to life” instead of “turned on to drugs.” Linkletter also blamed the people he called “missionaries” for making drugs attractive and available to younger people. And he singled out Dr. Timothy Leary, whom Linkletter called “a poisonous and evil man” for promoting marijuana and LSD. With his daughter’s death, Linkletter became involved in the anti-drug campaign, giving talks on the issue around the country, and railing against permissiveness in society and what he believed to be the threat to family values.

December 1969: News story by United Press International reporting on Art Linkletter’s speech before the Governors Conference on Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs (this account appeared in The Bulletin, Bend, Oregon, Dec. 3rd, 1969, p. 1).

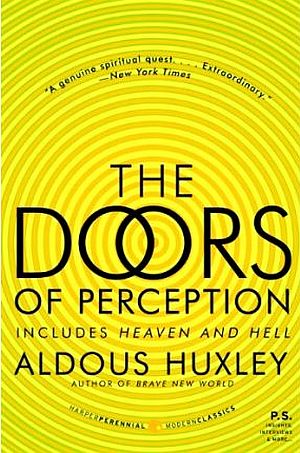

Some years later, on a TV show, Linkletter would again attack Leary, saying that his daughter and her generation believed there was nothing wrong with LSD because Timothy Leary had claimed it was “Gods’ gift to young people.” Linkletter also said on that show that Leary “happened to be an intellectual, a university-based guru, and gave the youngsters a kind of rallying point.” They weren’t just talking about hippies touting the drugs, explained Linkletter, “they were talking about an intellectual leader. And he [Leary], by saying these things, was giving them an additional argument for experimentation…” Linkletter added that Leary wasn’t alone in promoting the drug scene, also pointing to Grace Slick of the Jefferson Airplane, poet Allen Ginsberg, and Aldous Huxly in his book, The Doors of Perception, “all of whom were promoting the glories of drug abuse in what was a drug world.”

Yet, by the mid and late 1970s, some startling revelations about drugs and LSD would come from a somewhat unexpected quarter.

|

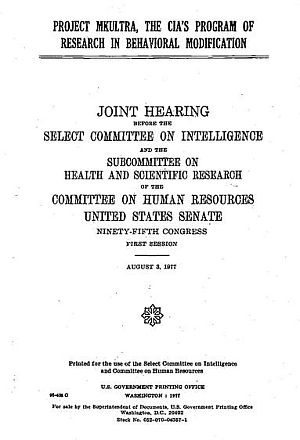

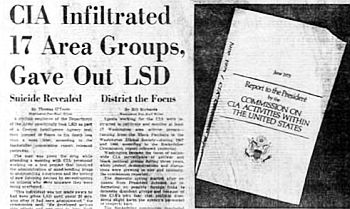

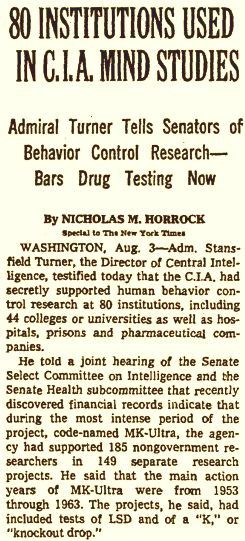

“CIA Does LSD”  Part of the front page of the Washington Post, June 11, 1975, reporting on Rockefeller Commission findings that the CIA conducted LSD experiments. including one in which a U.S. Army scientist had died (i.e.,:"Suicide Revealed" sub head). A CIA research program code named Project MK-ULTRA administered LSD to CIA employees, military personnel, doctors, other government agents, prostitutes, mentally ill patients, and members of the general public to study their reactions, often without the subject’s knowledge. None of this was known publicly at the time, and only surfaced in the mid-1970s when the Rockefeller Commission – led by then Vice President Nelson Rockefeller – issued its report on CIA activities within the U.S. The commission was created by President Gerald Ford in response to a December 1974 report in The New York Times that the CIA had conducted illegal domestic activities, including experiments on U.S. citizens. On June 11, 1975, the Commission’s report was front page news, with a dramatic Washington Post headline – “CIA Infiltrated 17 Area Groups, Gave Out LSD.” For a generation of young people who had been badgered by the federal government about the evils of drugs, with all kinds of insinuation about their recklessness and irresponsibility, this headline was a stunner and the height of hypocrisy: their own government, it turns out, was one of the biggest drug pushers of all.  Headlines and portion of story that appeared in the New York Times, August 4, 1977. In one LSD experiment gone awry was recounted in the case of Frank Olson, a 42-year-old government scientist was reported to have committed suicide after being given the drug. In late November 1953, Olson plunged to his death from the 13th floor of New York’s Statler Hotel, just opposite Penn Station. At the time, Olson’s death reported as a suicide of a depressed government bureaucrat who came to New York seeking psychiatric treatment. But 22 years later, the Rockefeller Commission report was released, detailing a litany of domestic abuses committed by the CIA. And with that report, some of the ugly truth began to emerge: Olson’s death was the result of his having been surreptitiously dosed with LSD days earlier by his colleagues. Still, there was more to come about the government and LSD in subsequent House and Senate investigations. In the mid-1970s, the Church Committee – named for Senator Frank Church (D-ID), and officially named the U.S. Senate Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities – conducted a wide-ranging series of hearings on the activities of the U.S. intelligence community (and also, in similar investigations, through the Pike Committee in the U.S. House of Representatives ). Among the Church Committee’s findings, for example, it reported that from 1954-1963, the CIA “randomly picked up unsuspecting patrons in bars in the United States and slipped LSD into their food and drink.” In 1977, a Freedom of Information Act request uncovered a cache of 20,000 documents relating to Project MK-ULTRA, which led to a joint hearing by the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence and the Senate Subcommittee on Health and Scientific Research in August 1977. These hearings produced a new round of revelations leading to more news headlines about the government and drug activity, such as the one above, “80 Institutions Used In C.I.A. Mind Studies,” reported by the New York Times, August 4, 1977. In 1984, the U.S. General Accounting Office (GAO) also issued a report on the topic, finding that Department of Defense, working with the CIA, gave hallucinogenic drugs to thousands of “volunteer” soldiers in the 1950s and 1960s. In addition to LSD, the Army also tested other hallucinogens. Many of these tests were also conducted under the MK-ULTRA program. Between 1953 and 1964, GAO reported, the program consisted of 149 projects involving drug testing and other studies on unwitting human subjects.There is a lot more detail on the House and Senate investigations and their findings – as well as a number of books on the topic – a subject well beyond the scope of this article, only offered here briefly in the context of the Leary story. For those interested in this issue, there are a number of sources listed at the end of this article in “Sources, Links & Additional Information” that provide beginning leads to further source material. |

Leary was arrested on drug charges several times. Here, he is escorted by U.S. Customs agents in October 1966 for failing to register at LaGuardia Airport as a drug offender on return from an international (Canadian) trip.

Arrests, Flight & Nixon

Timothy Leary, meanwhile, hit some rough water in the 1970s. His earlier 1968 arrest for possession of marijuana in Laguna Beach, California resulted in a 1970 conviction. He was sentenced to a 10-year prison term and began serving time at the California Men’s Colony in San Luis Obispo. At that point, Leary’s life turns into something of a Hollywood action movie script.

Not eager to serve his sentence, Leary engineered an escape from the minimum security prison in September 1970. He climbed to a rooftop and up a telephone pole, then going hand-over-hand along a cable across the prison yard, above and beyond barbed wire, he dropped to the road below outside the prison. There he was helped by members of the leftist Weathermen underground group who helped move him and his wife Rosemary to Algeria. There he was given sanctuary of sorts with Eldridge Cleaver’s American government-in-exile.

The Nixon Administration, meanwhile, had become quite revved up about Timothy Leary – owing in part to Art Linkletter’s concerns, already mentioned, but also for other reasons. Nixon Administration lawyers had lost a May 1969 Supreme Court appeal in Leary v. United States – which sought to overturn an earlier Leary marijuana conviction. But in that case, the court found the Marijuana Tax Act of 1937 unconstitutional. And when Nixon launched Operation Intercept in September 1969, a drug enforcement action to stop the flow of marijuana coming across the Mexican border, Leary had countered with Operation Turn-On, urging his followers to grow their own and help spawn a national industry. “They lost the war in Vietnam,” Leary said at the time, “and now they are using the same techniques in the war on pot.”

2018 book by Bill Minutaglio and Steven L. Davis, subtitled, “Timothy Leary, Richard Nixon and the Hunt for the Fugitive King of LSD,” focusing on Leary’s flight. Click for copy.

So when Leary escaped from prison in September 1971 and went on the lamb, Nixon and his people decided to make him even more of a special target. In a 2018 book on Leary’s flight from the law – The Most Dangerous Man in America: Timothy Leary, Richard Nixon and the Hunt for the Fugitive King of LSD – authors Bill Minutaglio and Steven L. Davis, say that Nixon and his inner circle sought to use Leary as part of a “diversionary politics” to help steer the national mood away from the Vietnam War, ongoing protests, and other domestic difficulties. According to co-author Bill Minutaglio:

…Nixon needed a poster child — someone to vilify in his burgeoning war on drugs. …The war in Vietnam was still raging, and there was a lot of violence and aggressive activism on the streets… [W]e stumbled across…a tape where Nixon at the White House with many of his infamous colleagues — a lot of the Watergate-era folks — had gathered around and said: “You know what? To salvage your approval ratings, to misdirect attention away from this flagging war in Vietnam, a stagnant economy, your swooning poll numbers, we need to find a villain, a guy in a black hat, and why not choose Timothy Leary? He’s sort of the godfather of the countercultural revolution. And we can make him public enemy No. 1.”

Algeria, circa 1970: Timothy Leary with Brian Barritt, an English counter-culture author and artist who collaborated with Leary during his years in flight.

Leary and Cleaver, meanwhile, had their own disagreements, and after a time, Leary was in flight once again. This time he ended up in Switzerland, where he found a benefactor and protector for a time. But the Nixon Administration was hot on his heels. Nixon sent Attorney General John Mitchell to Switzerland in a bid to have the Swiss hand over Leary. But Switzerland ruled in favor of Leary, arguing that his marijuana conviction was a minor offense, though the Swiss did jail him for a short time in response to Mitchell; but they would not extradite him.

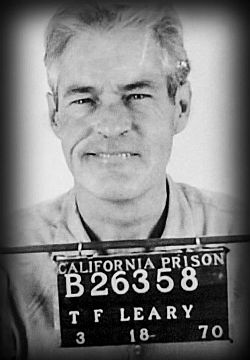

March 1970 California prison photo of Timothy Leary before his September 1970 escape.

In prison, and seeking a way to reduce his time, Leary began cooperating with prosecutors, naming names and writing incriminating articles, which caused a falling out among some of his followers. In 1974, he was publicly denounced by a group that included Arthur Miller, Dick Gregory, Judy Collins and Country Joe McDonald. At a press conference that included Leary’s son, Jack, Allen Ginsberg, Richard Alpert (then Ram Dass) and Yippie leader Jerry Rubin, Leary was called an “informant,” a “liar” and a “paranoid schizophrenic.” Yet Leary would maintain that no one was ever prosecuted based on any information he had given to the FBI. In 1976, Leary was released from prison by Governor Jerry Brown.

Later Years

For the next 20 years or so, Timothy Leary became something of a notorious and caricatured figure, sometimes branded as a loony who had “fried his brain on acid.” Yet at times, he seemed to be into the next new thing, reinventing himself as he went. In the early 1980s, he tapped into the information age, attracting the attention of the young and wired. He embarked on some college lectures touting the future of computers and also worked on a software line called Futique and helped design programs to digitize thought-images. He believed the internet was going to empower people on a massive scale and at one point proclaimed the PC would be “the LSD of the 1990s.”

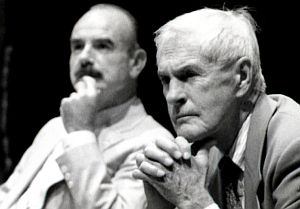

G. Gordon Liddy (left) and Timothy Leary (right) at one of their joint appearances in the 1980s.

A 1997 paperback edition of Timothy Leary’s 1983 autobiography, “Flashbacks,” which covers his controversial career. Click for copy.

…As the era of drugs, sex and rock ‘n’ roll unfolded, it seemed that Mr. Leary was at every scene, alongside a strange cast of famous characters. He took psilocybin trips with, among others, Arthur Koestler, Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, Robert Lowell, Maynard Ferguson and William Burroughs. He was arrested by G. Gordon Liddy. He sang “Give Peace a Chance” with John Lennon and Yoko Ono. As a fugitive on drug charges, he lived in Algeria with Eldridge Cleaver and dined in Gstaad with Roman Polanski; back at Folsom prison in…

Although Leary had his fans into his later years, and has followers still today, those in the scientific community who worked on psychedelic drugs for their medicinal and psychotherapy potential are not among his admirers. For Leary’s proselytizing and popularizing LSD in the 1960s was not viewed positively by this community, their research essentially shut down by the LSD backlash that had occurred. Serious scientific research into the psychoactive drugs and their possible beneficial uses was set back decades by some estimates. And it wasn’t just LSD, but dozens of other drugs seen as possible treatments for depression, post-traumatic syndrome, alcoholism, and end-of-life applications. Now in recent years, some 50 years after many of these substances were first studied, research has resumed. Even Harvard is studying LSD again.

Dr. Timothy Leary at his desk, circa mid-1960s.

Readers of this story may also find the following of interest: “White Rabbit: Grace Slick: 1965-2010s” (about famous Jefferson Airplane “Alice-in-Wonderland” song with alleged drug imagery and innuendo by feisty lead singer that became political lightening rod for Nixon Administration and others); “The Pentagon Papers: 1967-2018” (story of the secret Pentagon history of Vietnam War that was leaked by Daniel Ellsberg to the New York Times and Washington Post, touching off historic 1971 freedom-of-the-press confrontation between the Nixon Administration and the publishers, also spawning 2018 Oscar-nominated film, “The Post.”); “Enemy of the President, 1970s” (profile of Paul Conrad’s political cartoons, with special attention to those on Richard Nixon and Watergate); and, “The Frost-Nixon Biz, 1977-2009” (the David Frost/Richard Nixon TV interviews regarding the Watergate scandal).

Additional stories on the 1960s and 1970s can be found in the period archives for those respective decades. Stories on music or politics can be found respectively at the “Annals of Music” and “Politics & Culture” category pages. Thanks for visiting – and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research and writing at this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

____________________________________

Date Posted: 26 November 2014

Last Update: 20 March 2020

Comments to: jdoyle@pophistorydig.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Legend of a Mind: Timothy Leary, 1960s,”

PopHistoryDig.com, November 26, 2014.

____________________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

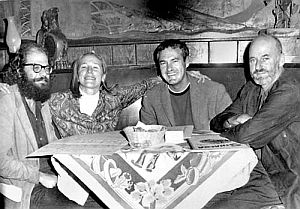

1960s San Francisco: Allen Ginsberg, Peggy Hitchcock, T. Leary & Lawrence Ferlinghetti at Sinaloa club. |

1966: Allen Ginsberg, Timothy Leary, and Ralph Metzner at Millbrook Estate, New York. |

Aldous Huxley, 1920s. Huxley and Timothy Leary met and corresponded in Huxley’s later years, during the 1960s. |

“Moody Blues,” in Holly George-Warren and Patricia Romanowski (eds), The Rolling Stone Encyclopedia of Rock & Roll, Rolling Stone Press, New York, 3rd Edition, 2001, pp. 665-667.

Bruce Eder, “Biography, Moody Blues,” All Music.com, 2009.

“Legend of a Mind,” Wikipedia.org.

“In Search of the Lost Chord,” Wikipedia.org.

Roger Catlin, “Future, Past Merge In Fully Orchestral Moody Blues Tour,” Hartford Courant (Hartford, CT), June 12, 1996.

In Search Of The Lost Chord (liner notes, etc.), Yuku.com, 2005 posts.

Brian Travers, Retro Review: The Moody Blues / In Search of the Lost Chord, mcquad- rangle.org., September 7, 2005.

“Medicine: Dream Stuff,” Time, Monday, June 28, 1954.

Joe Hyams, “How A New Shock Drug Unlocks Troubled Minds,” This Week (Sunday Supplement magazine), November 8, 1959.

Dr Paul Terrell (as told to Ted Levine), “I Went Experimentally Insane,” Argosy, October 1959.

Timothy Leary, The Interpersonal Diagnosis of Personality, New York: John Wiley and Sons Inc, 1957.

Richard Alpert & Timothy Leary, “The Politics of Consciousness Expansion,” The Harvard Review, Summer 1963, Vol. 1, No. 4, pp. 33-37.

Andrew T. Weil, “The Strange Case of the Harvard Drug Scandal,” Look, November 5, 1963.

“A Straight Scene,” Newsweek, July 22, 1964, p. 74.

John Kobler, “The Dangerous Magic of LSD,” Saturday Evening Post, November 2, 1963, pp.30-40.

Richard Alpert, Timothy Leary, and Ralph Metzner, The Psychedelic Experience: A Manual Based on the Tibetan Book of the Dead, New Hyde Park, NY: University Books, 1964.

KRON TV News, Press Conference scenes, Timothy Leary & Richard Alpert, Re: Their Use and Study of the Hallucinogenic Drug LSD. October 28th 1964,

Nancy Moran, “Sex, Poetry, Music; LSD Simulation Session [with Timothy Leary] Lures 16 to ‘Ecstatic Experience’… Everyone Meditates ‘What Is Reality’,” Washington Post/Times Herald, November 1, 1965, p. B-3.

“LSD: The Exploding Threat of the Mind Drug that Got Out of Control,” Life, March 25, 1966.

Barry Farrell, “Scientists, Theologians, Mystics Swept Up in a Psychic Revolution,” Life, March 25, 1966.

“LSD and Mind Drugs,” Cover Story, Newsweek, May 6, 1966, pp. 59-64.

“The Growth of a Mystique” (on Leary), Newsweek, May 6, 1966, pp. 60-61.

“Senate Testimony on LSD,” Washington Post, May 26, 1966, p. A-3.

Jean M. White, “Leary Proposes a Ban on LSD Except in ‘Psychedelic Centers’; Regret Expressed,” Washington Post/Times Herald, May 27, 1966, p. A-2.

“Essay: LSD,” Time, Friday, June 17, 1966.

“Night Spots That Make You Feel Like LSD,” Saturday Evening Post, October 22, 1966.

Timothy Leary, Press Conference, Fairmont Hotel, San Francisco, December 12, 1966, as reported in the San Francisco Oracle, December 16, 1966.

George B. Leonard, “Where The California Game is Taking Us,” Look, June 28, 1966.

Timothy Leary, Psychedelic Prayers After the Tao Te Ching, New Hyde Park, NY: University Books, 1966.

David Solomon, LSD: The Consciousness Expanding Drug, Berkeley, 1966 (with introduction by Timothy Leary).

John Cashman, The LSD Story, New York: Fawcett, 1966,

“Leary Arrested, Says Many Use LSD at Harvard,” The Harvard Crimson, October 13, 1966.

The Psychedelic Experience (LP): Readings from the Book,”The Psychedelic Experience: A Manual Based on the Tibetan Book of the Dead,” 1966 (LP recording), 2003 (CD) American Folkways.

Alex Henderson, Review, “Timothy Leary: Turn On, Tune In, Drop Out”(LP), AllMusic.com.

“History of the Hippie Movement,” Wikipedia.org.

Joyce Haber, “Dr. Leary–Is This Trip Necessary?,” Los Angeles Times, February 5, 1967, p. C-8.

Charles Champlin, “Leary LSD Film at Cinema,” Los Angeles Times, May 12, 1967, p D-15.

Timothy Leary, Start Your Own Religion, Millbrook, New York: Kriya Press. 1967.

J.M. Flager,“Drugs and Mysticism: The Visions of ‘Saint Tim,’ Look, August 8, 1967, pp. 18-22.

“The Hidden Evils Of LSD,” Saturday Evening Post (cover story), August 12, 1967.

“Court Upholds Fine, Sentence Against Leary,” Los Angeles Times, September 30, 1967, p. 2

Don Robinson and Richard Blumenthal, “Leary Drops-In, Urges Students To ‘Drop-Out’ at NSA Debate,” Washington Post/Times Herald, August 18, 1967, p. A-3.

Larry Keenan (photographer), “1960s & 1970s Counterculture Gallery.”

Timothy Leary, High Priest, American Library/World Publishing Co.; 1st Edition, January 1, 1968, 353pp.

Ralph Dighton, “Leary Prepares to Play the ‘Messiah Game’; Life Is Different, Controlled Society,” Washington Post/Times Herald, February 22, 1968, p. F-1.

Timothy Leary, The Politics of Ecstasy, New York: Putnam, 1968.

“Bed-In,” Wikipedia.org.

Richard Nixon, et. al., “Remarks at a Bipartisan Leadership Meeting on Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs,” Washington, DC, October 23, 1969.

UPI, “Linkletter Speaks Out; Dr. Leary Blasted As Drug Promoter,” The Bulletin (Bend, Oregon), December 3, 1969, p. 1.

“Turn On, Tune In, Drop Out,” Wikipedia.org.

“Algeria Grants Timothy Leary Political Asylum,” Washington Post/Times Herald, October 21, 1970, p. 24.

“Leary Calls Violence Necessary” [remarks from Cairo, Egypt], Washington Post/Times Herald, October 31, 1970, p. A-10.

“Leary Tells Young to Quit Drugs, Take Up Revolt,” Washington Post/Times Herald, February 25, 1971, p. A-28.

Timothy Leary, Confessions of a Hope Fiend, New York: Bantam, 1973.

Timothy Leary, NeuroLogic, San Francisco, CA: Starseed Information Center, 1973.

“Tim Leary and the Long Arm of the Law,” Rolling Stone, March 15, 1973.

“CIA Infiltrated 17 Area Groups, Gave Out LSD,” Washington Post, June 11, 1975, p. 1.

“Project MKUltra,” Wikipedia.org.

“Project MKULTRA,” New York Times (PDF file, 1977 Committee hearings).

“Rockefeller Panel Findings on CIA Domestic Activities,” Washington Post, June 11, 1975, pp. A8-A10.

Austin Scott and Bill Richards, “LSD Test Data Is Missing From Rockefeller Report,” Washington Post, July 13, 1975, p. 1.

Bill Richards, “School, Army Tested LSD On Hundreds,” Washington Post, July 17, 1975, pp. A-1, A-2.

Stephen J. Lynton, “Army ‘Guinea Pig’ In 1963-64 Tells Of ‘Hallucinations’,” Washington Post, July 20, 1975, p. A-3.

Jack Anderson and Les Whitten, “Soldiers in Mock Battle Given LSD,” Washington Post, July 30, 1975, p. B-11.

Bill Richards, “AF [Air Force] Paid For LSD Studies; Drug Given To Children, Mental Cases AF Financed LSD Studies At 5 Colleges,” Washington Post, July 31, 1975, p. A-1.

Alice Bonner, “100 Professionals Took LSD Dosage,” Washington Post, August 4, 1975, p. A-5.

Bill Richards, “Navy Reveals LSD Use On Depressed Patients,” Washington Post, August 8, 1975, p. C-3.

Bill Richards, “LSD Used in U.S. Interrogation,” Washington Post, September 13, 1975, p. A-2.

Bill Richards, “Army Plans No Action On 900 in LSD Tests [from 1959 to 1967],” Washington Post, September 30, 1975, p. A-11.

Nicholas M. Horrock, “80 Institutions Used In C.I.A. Mind Studies,” New York Times, August 4, 1977.

John Jacobs,“The Diaries Of a CIA Operative,” Washington Post, September 5, 1977, p. A-1.

Timothy Leary, The Game of Life, Los Angeles: Peace Press, 1979.

Albert Hofmann, LSD, My Problem Child, McGraw-Hill, January 1, 1980, 209pp.

Timothy Leary, Changing My Mind, Among Others: Lifetime Writings, Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1982.

Timothy Leary, Flashbacks: An Autobiography, Los Angeles: J.P Tarcher, Inc., 1983.

Laura Mansnerus, Obituary, “Timothy Leary, Pied Piper Of Psychedelic 60’s, Dies at 75,” New York Times, June 1, 1996.

Joceylyn McClurg, “An Experimental Life: Clare Boothe Luce Turned On, But Never Dropped Out,” Hartford Courant(CT), November 16, 1997.

Robert Forte (ed), Timothy Leary: Outside Looking In: Appreciations, Castigations, and Reminiscences – Ram Dass, Andrew Weil, Allen Ginsberg, Winona Ryder, William Burroughs, Albert Hofmann, Aldous Huxley, Terence McKenna, Ken Kesey, Huston Smith, Hunter S. Thompson, & Others, Inner Traditions / Bear & Co., March 1999, 352 pp.

Timothy Leary, Change Your Brain, Berkeley, CA: Ronin Press, 2000.

Timothy Leary, Politics of Self-Determination, Berkeley, CA: Ronin Press, 2000.

Timothy Leary, Your Brain Is God, Berkeley, CA: Ronin Press, 2000.

BBC Documentary, “Timothy Leary: The Man Who Turned On America,” June 2000.

Tom Mcnichol, “Tricky Dick’s Guide to Drinking and Toking; In Newly Released Transcripts, Richard Nixon and Art Linkletter Struggle to Fathom the Differences Between Demon Rum and Dope,” Salon.com, April 15, 2002.

Joe Holley, Obituary, “John K. Vance; Uncovered LSD Project at CIA,” Washington Post, June 16, 2005.

Robert Greenfield, Timothy Leary: A Biography, New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2006, 704pp.

Nick Gillespie, “Psychedelic, Man,” Washington Post, Book Review of Robert Greenfield’s Timothy Leary: A Biography, June 15, 2006.

John Higgs, I Have America Surrounded: A Biography of Timothy Leary, Barricade Books, August 2006, 1st Edition, 320pp.

Louis Menand, “Acid Redux: The Life and High Times of Timothy Leary,” The New Yorker, June 26, 2006.

Joseph L. Flatley, “From The Vaults: Two Interpretations of Timothy Leary.”

“Timothy Leary Bibliography,” Wikipedia.org.

John Cloud, “Was Timothy Leary Right? No, but New Research on Psychedelic Drugs Shows Promise for Their Therapeutic Use,” Time, April 19, 2007.

John Cloud, “When the Elite Loved LSD,” Time, April 23, 2007.

Stephen Siff, “Henry Luce’s Strange Trip: Coverage of LSD in Time and Life, 1954-68,” Journalism History, Vol. 34, No.3, 2008, pp 126-134.

Don Lattin, The Harvard Psychedelic Club: How Timothy Leary, Ram Dass, Huston Smith, and Andrew Weil Killed the Fifties and Ushered in a New Age for America, New York: Harper, January 2010, 272 pp.

M. J. Stephey Q&A, “The Harvard Psychedelic Club,” Time, January 11, 2010.

Philip Messing, “Did the CIA test LSD in the New York City Subway System?,” New York Post, March 14, 2010.

Jack Shafer, “The Time and Life Acid Trip: How Henry R. Luce and Clare Boothe Luce Helped Turn America on to LSD,” Slate.com, June 21, 2010.

Sue Blackmore, “Will Timothy Leary’s papers turn us on to LSD? Leary Was Far from Crazy in Claiming Psychedelics Have Healing Powers. Hopefully the Sale of His Papers Will Help Us Learn More,” Guardian.com, June 18, 2011.

Jon Hanna, “Andrew Weil’s 1963 Report on Harvard’s Firing of Richard Alpert,” Erowid.org, October 2011.

“MK Ultra News Articles,” The Hubris of Boz, Friday, December 21, 2012.

“Timothy Leary’s ‘Dangerous’ Psychedelic Album | You Can Be Anyone this Time Around 1970,” FromTheBarrelHouse.com, September 25, 2013.

“Acid Dreams (book),” Wikipedia.org.

Scott Staton, “Turn On, Tune In, Drop by the Archives: Timothy Leary at the N.Y.P.L.”[NY Public Library], The New Yorker, June 16, 2011.

Theodore P. Druch, Timothy Leary and the Madmen of Millbrook [Kindle Edition].

Sheila Weller, “Suddenly That Summer,” Vanity Fair, July 2012.

Tom Couillard, “Depth of Field Icons: G. Gordon Liddy and Timothy Leary,” St Thomas.edu, November 19, 2013.

__________________________