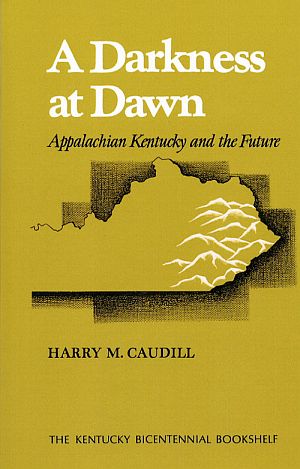

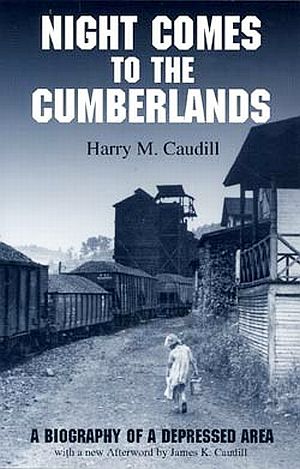

Harry Caudill’s 1983 book on the history of Kentucky exploitation by steel and mining companies, published by the University of Illinois Press. Click for copy.

Kentucky then, and still today, is besieged by corporate interests who came for the region’s natural wealth, primarily its coal. Caudill not only did battle with the coal barons, but also local corruption and local politicians – often the handmaidens of the outside interests. After years of battling, Caudill succeeded in drawing attention to the plight of Kentucky and the larger Appalachian Region. The cover of one of his books is displayed at right, as its title and subtitle aptly capture what Harry Caudill railed against for much of his life.

A lifelong resident of Kentucky’s Letcher County, Harry Monroe Caudill was born near Whitesburg on May 3, 1922. His ancestors helped settle the county. After high school, Caudill served in the U.S. military and saw action in Italy during WWII. Following the war, he received his law degree from the University of Kentucky in 1948. That year he began practicing law in Whitesburg. But he soon turned to politics, elected to the Kentucky legislature in 1954, 1956 and 1960. He also rose on the national stage with the 1963 publication of Night Comes to the Cumberlands, a book which eloquently described the forces of Appalachian poverty and exploitation, helping to spur the Kennedy and Johnson administrations to help the region.

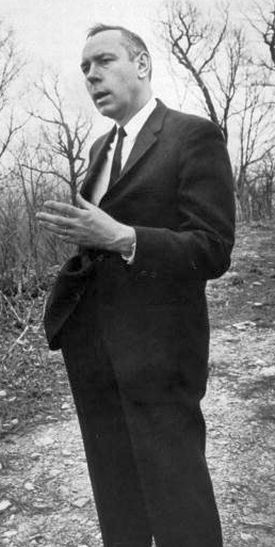

Harry Caudill of Kentucky.

Becoming something of a national figure in the 1960s, Caudill was also profiled in articles by noted writers such as Calvin Trillin of The New Yorker and noted historian, David McCullough, then writing for American Heritage magazine.

Caudill would also testify before various committees of the U.S. Congress on topics ranging from balanced economic development to the problems of older Americans in rural areas. But the issue that helped bring Caudill to state and national attention between the 1950s and 1970s was strip mining for coal.

1967: Harry Caudill, photographed in Kentucky by Life magazine photographer Bob Gomel.

Strip Mining

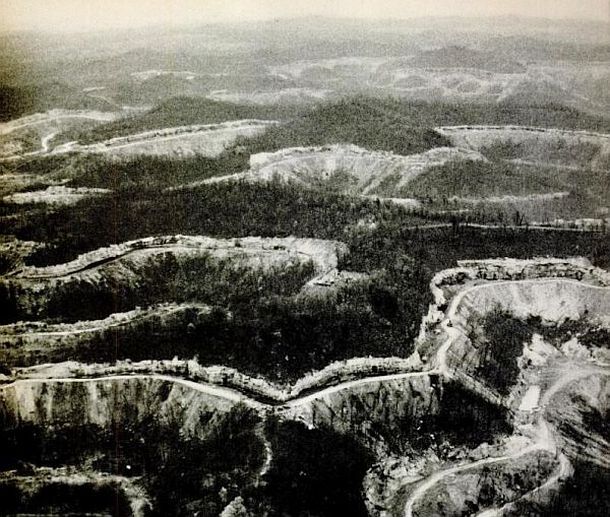

Strip mining in Kentucky and elsewhere had gone on for decades before Harry Caudill arrived on the scene, but after World War II the technology had moved well beyond the “pick-and-shovel” stage. In eastern Kentucky especially, the practice of “shoot and shove” contour strip mining was notorious. Miners gouged into hillsides with mechanized shovels and dozers, establishing a “bench,” and from there would snake around mountain sides for miles (see photo later below). In the process, tons of dirt and spoil were pushed “over the side,” off the bench and down the mountain sides, clogging and polluting streams below. In its wake, a ruinous moonscapes remained, with dangerous highwalls, acid mine drainage, mudslides and flooding. Hardscrabble farmers and rural communities often paid the price.

In the 1950s, residents of Letcher, Harlan, Knott, Perry and other mountain counties in Kentucky began to advocate a ban on strip mining. Regulatory control bills had been offered in 1948 and 1952 but did not pass. By the time Harry Caudill took his seat in the legislature in 1954, a weak measure was adopted, requiring operators to post a paltry $100 to $200 bond per acre. In those days, few operators even bothered to get a permit, and a court decision exempted augur mining- a horizontal drilling technique that often added to the damage. Then the governor abolished the regulatory agency. Eastern Kentucky continued to be ravaged.

Many operators who held mineral rights obtained under the notorious “broad from deed”– a pernicious bit of legalese that swindled rightful landowners out of their mineral rights decades earlier – ran roughshod over landowners. Coal operators did not bother, nor were they bound, to ask the landowners for permission to mine. Neither did they repair the land or abate the damage in the wake of their mining. Blasting and bulldozers shattered windows, knocked homes off foundations, covered roads with debris, uprooted forests, and ruined cropland – typically without compensation to landowners.

Circa 1967: Aerial view of contour strip mining's handiwork in Eastern Kentucky, with gouged mountainsides running for miles to the far horizon. Source: “These Murdered Mountains,” Life magazine, January 12, 1968, photo by Bob Gomel.

In 1960, Harry Caudill had introduced the first bill in the Kentucky legislature to ban strip mining. But more pressure to develop Kentucky and Appalachian coal fields came from a New Deal agency designed to help the region – the Tennessee Valley Authority. In 1961, TVA decided to get into the coal business and signed long-term contracts to buy 16.5 million tons of strip-mined coal to supply its power plants. In 1962, Peabody Coal Co. was among those answering the call, as it opened the Sinclair Surface Mine in Muhlenberg County in Western Kentucky, there operating a gargantuan 20-story shovel nick-named “Big Hog” that supplied coal for years to the TVA Paradise Fossil Plant (see “Paradise” story at this website). Back in Eastern Kentucky, more strip mines opened up as well, arousing citizen anger. One local resident named Raymond Rash gathered petitions from one thousand supporters calling for a strip mine ban. Bu neither Caudill’s bill in the legislature nor the citizen petitions made much difference, as a 1963 revision of the state’s strip-mine control law would be adopted. But that law was all window dressing and had little effect on stripping. Meanwhile, Harry Caudill would publish the book that would bring he and his Appalachian cause more national notice.

Cover of best-selling 1962 book by Kentucky author, Harry Caudill, whose portrayals of Appalachia and the ravages of strip mining were revelations to many. Click for copy.

“Night Comes…”

In 1962, Harry Caudill’s Night Comes to the Cumberlands was published as an Atlantic Monthly Press book by Little, Brown & Co. of Boston, Massachusetts.

“In Night Comes to the Cumberlands, “ wrote the publisher on the back of early paperback editions, “author Harry M, Caudill focuses on the terrible social sore of squalor, ignorance and demoralization among the inhabitants of the Cumberland region of eastern Kentucky. The ugly practice of coal mining plundered the hills, leaving the natives jobless and hopeless among refuse-clogged streams, sterile fields, and abandoned ‘company towns.’ And these shocking conditions prevail in the Cumberlands even today.”

Excerpted on the book’s back cover as well were selected review blurbs: “Few books of recent years present a more devastating but poignant account of the degradation of a people than the story of the Kentucky mining regions,” from the Minneapolis Sunday Tribune, and, “…One cannot come away from reading Night Comes to The Cumberlands without a terrible sense of indignation and urgency,” said JFK brother-in-law and Peace Corps director, Sargent Shriver.

“Caudill’s book,” wrote then Secretary of the Interior, Stewart Udall in the book’s preface, “is a story of land failure and the failure of men. It is reminiscent of such earlier works as Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle, Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, and Agee’s Let Us Now Praise Famous Men….” Like those books, said Udall, Caudill’s Night Comes to the Cumberlands “speaks eloquently to the American conscience”.

In the book, after providing a geological and cultural overview of the region and its heritage, Caudill moved directly to the coal industry’s dire effect on the land and its people:

“…Coal has always cursed the land in which it lies. When men begin to wrest it from the earth it leaves a legacy of foul streams, hideous slag heaps and polluted air. It peoples this transformed land with blind and crippled men and with widows and orphans. It is an extractive industry which takes all away and restores nothing. It mars but never beautifies. It corrupts but never purifies.”

April 1964: President Lyndon B. Johnson during a visit with Tom Fletcher and family in Inez, Kentucky announcing his “War on Poverty” program.

“But the tragedy of the Kentucky mountains transcends the tragedy of coal. It is compounded of Indian wars, civil war and intestine feuds, of layered hatreds and of violent death. To its sad blend, history has added the curse of coal as a crown of sorrow.”

What Caudill did so successfully with Night Comes… was to point up, in 1962, that Appalachia had become an island of poverty in a national sea of plenty and prosperity. The book was at least partially credited with sparking the creation in 1964 of the Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC), a federal agency to assist Kentucky and twelve other states in the Appalachian Mountains. After Caudill’s book came out, President John F. Kennedy appointed a commission to investigate conditions in the region, and his successor, Lyndon B. Johnson, made Appalachia and the ARC a focus of his “War on Poverty.” Johnson, in fact, came to Inez, Kentucky, meeting with a local family there as part of his “War on Poverty” campaign. Subsequently more than $15 billion in federal aid was invested in the region over twenty-five years.

February 1968: Harry Caudill showing U.S. Senator Robert F. Kennedy (D-NY) some of Eastern Kentucky during Kennedy’s tour of Appalachia.

Back in Appalachia, as the fight to control strip mining began moving from state legislatures to the federal level in the late 1960s, the national press began to pay more attention to the issue. One story that ran appeared in the January 12th 1968 issue of Life magazine. Life was one of the very prominent weekly magazines of that era, and it titled its strip mining story: “These Murdered Old Mountains – Kentucky Operators are Violently Defacing the Land and Ruining Lives.” The story was given prominent play in the magazine over several pages, and it included some dramatic photos of strip mining’s effects, one of mountainside strip mining stretching to the horizon shown earlier. It also included accounts of strip mining damaging homes, unearthing a grave in a family cemetery, causing land-scouring mudslides that destroyed homes, and others that wiped out gardens or clogged streams that flooded and backed-up into people’s homes.

The home at the bottom of this 1968 photo near Hazard, KY was formerly located half way up the mountainside, its demise by massive mudslide precipitated by the removal of forest and strip mining for coal. / Life

“…When man destroys his land, he begins to destroy himself. I believe that… We’re laying a precedent for the destruction of vast areas. This is not an abstraction. We’re talking about millions of acres, at a time when we’re on a collision course between diminishing land and increasing population. This land may not recover fully for a century. If we have any consideration for posterity, of continuity, of meaning or design in the human equation, then the land is the most important heritage we can pass down. Those narrow few inches of topsoil laid down over so man centuries are the very basis of life. That explains man’s atavistic attachment to the earth – and it explains why the mass destruction of land is somehow obscene.

“You see this in these murdered old mountains and in the impact on the spirit, the soul, the mind of the these people.”

Life’s correspondent noted that the Kentucky coal industry regarded Caudill as an “impractical visionary who doesn’t grasp the real significant of progress,” quoting one strip miner who had gone to college with Caudill, saying: “he was a son of a bitch then and he’s a son of bitch now.” Caudill’s retort was simply, “Strip mining has become a very big business.”

Caudill would also travel to Washington to lend his voice to the strip mine debate. In the summer of 1968, he testified before a Senate committee then considering three proposed bills that had been introduced to regulate strip mining, including one from the Johnson Administration. Caudill stated that stripping should only be allowed where reclamation of the land could be assured – and according to Caudill, none of the pending bills met that standard. He also stated that strip mining should be prohibited in much of southern Appalachia where the slopes were so steep that reclamation and restoration of the land to it former state was impractical and impossible. Areas of special beauty and important to wildlife should also be off limits to strip mining. And finally, as part of any worthy strip mining bill would be a program to restore abandoned mine lands – of which there were many thousands of acres already stripped and abandoned in Caudill’s Kentucky, as well as thousands more in 25 other states, a problem which still festers to this day. An abandoned mine fund, said Caudill and others, should be financed by a special tax on the extractive industries.

Although some bills were introduced in Congress during the late 1960s and early 1970s to regulate strip mining nationally, they made little headway. In 1971, over a dozen bills were introduced, including one by the Nixon administration. In February 1971, Rep. Ken Hechler (D-WV) introduced a bill to ban all surface coal mining. But turning such measures into law would be uphill fights in Congress, where the coal industry had many friends.

Cover of Harry Caudill’s 1971 book, “My Land is Dying,” which covered more of the Appalachian struggles with coal and mining. Click for copy.

Back home, Caudill and his neighbors tried unsuccessfully to stop a big Bethlehem Steel company strip mine in Letcher County in 1969. That operation — begun by the Beth-Elkhorn Corporation in June 1969 — eventually took out more than a thousand acres of heavily timbered land, much of it owned by the company, in order to begin strip mining 7,000,000 tons of coal found in three near-surface seams.

Undated photo of citizens demonstrating for ending the broad form deed in Kentucky.

Holders of mineral rights under the broad form deed could come after any coal, gas and oil on the property, destroying the surface land even if the surface owner objected. It took years to change the law; not until 1988 when an amendment to the state constitution was adopted with the help of the citizen group, Kentuckians for the Commonwealth.

Harry Caudill was also quite forceful on why extractive industries in the Appalachian region should have been taxed more in order to improve the lot of the larger community. In a 1975 interview with the Mountain Call, for example, he said:

“…Instead of letting the coal barons plunder these mountains at will and get off scot-free the way we’ve done, let’s say we started taxing the big coal companies fairly back in their early days. And that we used the money collected to provide education for the people who lived here in the hills from which all that black wealth was taken.“[L]et’s say we started tax- ing the big coal companies fairly back in their early days. And that we used the money collected to provide education for the people who lived here in the hills from which all that black wealth was taken….” Would that education for its inhabitants early on have drastically changed Appalachia’s recent past and present?

“If we had had the will and the mind and the intelligence at the local level to levy a fair and adequate tax on coal and the other minerals taken from these mountains and then if we had put that money into good schools, we could have changed the whole situation.

“It wouldn’t have taken a very large tax, either. If we had collected just 10 cents a ton on coal moving out of here in the early years — and keep in mind that 10 cents then had the purchasing power of about 60 or 70 cents now — we would have had — in a county like Letcher, for example — $60 million to spend by 1955. Well, $60 million invested in schoolhouses and in roads to get children to school and in decently paid teachers would have created an entirely different situation….”

Caudill’s ideas on corporate responsibility and taxation gained some traction in the late 1970s, when George Atkins, former UK basketball player, Hopkinsville mayor, and state Auditor, sought the Democratic nomination for governor of Kentucky. Atkins advocated an increase in the severance tax if corporations failed to contribute voluntarily. Atkins later supported John Y. Brown who was elected governor and appointed Atkins as Finance Secretary. Harry Caudill, meanwhile, remained concerned with tax inequities, as well as with the large swaths of Appalachian land and resources controlled by absentee owners.

|

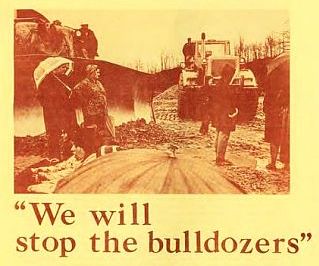

“Protest at Clear Creek*”  January 1972: Part of the contingent of 20 Kentucky women who occupied equipment at a Knott County strip mine site in protest. Meanwhile, back in the coalfields of Eastern Kentucky, a small group of protesters from Floyd County, Kentucky occupied equipment at the Ken Mack strip mine site above Clear Creek in Knott County. It was a cold, rainy day that January 1972 as 20 women moved to occupy loaders and bulldozers on the site in an angry and tense confrontation with workers. The women were all members of the group Save the Land and the People. During the 15-hour standoff, some workers tore down a tent the protesters had put up, and other male demonstrators who were not directly on the site (for fear they would provoke male workers) but at the gate area — including James Banscome and a reporter for the Mountain Eagle – were attacked by mine employees. When the protest ended, the women found two of their cars had slashed tires and smashed windows. Branscome’s car was overturned.  Published statement from women who blocked mining equipment in Knott Co., Kentucky, January 20, 1972. By the early 1970s, activist and citizen sentiment for controlling strip mining nationwide became increasingly focused on what might be possible in the U.S. Congress. Citizens in Appalachia by then had begun to convene regional and multi-state gatherings of activists, focusing on strategy for federal legislation. State legislatures during this period were also active, some passing bills for the first time, others amending existing laws, though typically not for the better. The coal industry would maneuver to pass weak state laws in hopes of forestalling federal regulation. However, a month after the Elijha Fork citizen action in Kentucky, tragedy struck the coalfields in West Virginia. On February 26, 1972, a large coal waste dam burst at Buffalo Creek, killing 125 people. The event galvanized concern about coal mining and related dangers, and helped spur the drafting and passage of regulatory strip mine bills in the U.S. House of Representatives during the early 1970s. But none of these would become law — at least not then. There was more to come on that fight. |

Still, even as he fought for improved regional leverage, Caudill seemed resigned to the fact that all the coal in Appalachia would be mined regardless of how it was regulated; he was not optimistic about controlling strip mining or the prospects for post-mining reclamation, even with stronger regulation. In a wide-ranging February 1975 interview with Caudill on Kentucky coal and other topics that was first published in The Mountain Call and later in Mother Earth News, Caudill – who was not opposed to all coal extraction, but abhorred surface mining – told his interviewers that Appalachia’s future did not look good.

“I think it’ll be mined into a desert,” he said. “We’ll dig till every lump of coal is taken out of these hills.” At the time, Caudill thought there might be some hope in a technique known as “coal liquefaction” – that is, to “liquefy coal in place… and pump it out of the ground instead of having to tear it out.” This, of course, was in 1975. “Otherwise,” he continued, left to strip mining, “it’s just a matter of time. Every hill will be decapitated and all the woods will be dug up. The streams will be congested with mud and the whole country will be ransacked…” And as time and further analysis would show, many of the “synthetic fuels” options touted about that time, including coal liquefaction, would offer no better outcomes.

1967: Life magazine photo of the after-effects of contour strip mining on a Kentucky mountainside showing the highwall cut, coal overburden sent down the hillside, and the remaining shelf, now used as a coal haul road.

As for the power of regulation to make the strippers reclaim the land, Caudill believed that was not likely either, as he explained in 1975:

“…Even if you passed a tough strip mining law now, you’d never know the difference.

“I had kind of hoped we’d do more than make strippers reclaim the land they tore up. I’d hoped we might stop stripping entirely.

“Not a chance. The pressures to keep it going are too powerful. You’re facing a tough combination when you line up against the rails, and the barge lines, and the mining companies, and the great land-owning companies, and the steel companies, and the utilities, and the rural electric co-ops, and the great foreign corporations that are loaded with billions of dollars and who want the coal.

“That combination could buy every voter in the country if necessary, and most people couldn’t care less. People, for the most part, don’t care anything about the land. We’re a people without any land ethic whatever…”

Despite Harry Caudill’s dire forecast in the mid-1970s, efforts persisted across the country and in Washington, D.C., to bring stronger national regulation to strip mining.

1977 Strip Mine Law

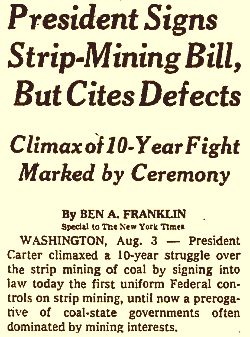

Front-page New York Times story by Ben Franklin on President Jimmy Carter signing the strip mine law, August 1977.

The legislative battle in Congress would rage through the mid-1970s in a process that would see more than 500 attempted amendments, good and bad, all kinds of legislative maneuvering to stop the bill, and two presidential vetoes. By 1977, following the election of Jimmy Carter, who said during his campaign that he would sign a strip mine bill, Congress passed the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977, which was signed into law by President Carter in August 1977. Harry Caudill was among those in the Rose Garden the day Carter signed the bill. Yet as this is written, more than 40 years later, the battle over strip mining – made more rapacious in recent years by way of “mountain top removal” techniques – continues, and its effects seem to bear out what Harry Caudill worried about in the mid-1970s.

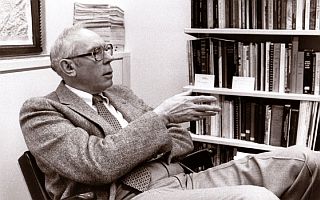

1983: Harry Caudill photographed in his office with a portion of his Appalachia library at right. Photo by John C. Wyatt, Herald-Leader newspaper, Lexington, KY.

University of Kentucky

In 1977 Harry Caudill gave up practicing law to become Professor of Appalachian Studies at the University of Kentucky (UK).“…[T]hrough his zeal for teaching, his ready rapport with people of all ages, and his well honed wit,” wrote the University of Kentucky on his biography page, “he quickly and effectively gained the respect of students and faculty alike.” And by all accounts, he continued to be his own man. Finding no suitable textbook on the region for teaching, for example, he compiled his own. Caudill remained a professor at UK until 1985.

Earlier, 1965 photo of Harry Caudill and his wife, Anne Frye Caudill.

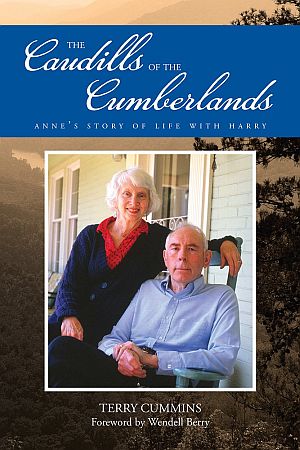

In October 1986, Caudill was honored at a “Banquet and Roast” at the University of Kentucky, part of the conference, “On the Land and Economy of Appalachia,” sponsored by the University’s Appalachian Center and also intended to celebrate the 25th anniversary of Night Comes to the Cumberlands. By 1990, Harry Caudill was spending much of his time at home. Experiencing increasing pain from a foot injury he suffered in WW II and battling Parkinson’s Disease. On the afternoon of November 29th, 1990, while facing Pine Mountain outside his Whitesburg home, Harry Caudill took his own life with a handgun. He left a note telling his wife that he loved her and did not want to burden her with his Parkinson’s Disease. In addition to his books, he left behind 80 newspaper essays, 50 odd magazine articles, and more than 120 lectures and speeches.

Rendering of Harry Caudill by Chris Ware.

Harry Caudill remained a critic and gadfly throughout his life, and regularly expressed his disillusionments with the remedies and fixes that were offered to help his region, some being created by his own prodding. The well-intentioned Appalachia Regional Commission, for example, ended up becoming its own political boondoggle, spreading its largesse over some 420 counties in 13 states. Even though hundreds of millions of dollars were poured into Kentucky and other states, with visible infrastructure and other improvements resulting, some believed the fundamental underlying problems still remained, and Harry Caudill was among the critics.

In his later years, some say Caudill turned bitter and jaded, though still searching for answers and solutions to help the seemingly intractable misfortune that gripped his homeland. Caudill in the mid-1970s, edged into some dicey territory when he began considering the highly controversial theories of Robert Shockley, and “dysgenics,” suggesting that a poor gene pool among Scotch-Irish and German descendants in the Kentucky mountains may have contributed to the region’s problems. In newspaper reporting that appeared in the Lexington Herald-Leader during 2012, some documentation and correspondence was unearthed suggesting that Caudill had adopted the dysgenics view with the intention of supporting research by Shockley into that arena in Eastern Kentucky. Yet his wife Anne, writing in reaction to the story, maintained that her husband’s excursion into the works and theories of Shockley, and his meeting with Shockley, were among hundreds of discussions and meetings he had with countless others over the years. His thinking in this area was, according to Anne Caudill, later abandoned. She wrote: “…Harry Caudill always spoke openly and wrote about his thinking. Was he always right? No one is. After a little further correspondence, he became dubious about the direction of the discourse and dropped it.” But for some of Harry Caudill’s friends and former colleagues, this transgression in thought and consideration caused a parting of ways.

The 2001 edition of “Night Comes to the Cumberlands” includes photographs of environmental damage, as well an Afterword written by Caudill’s son, James K. Caudill, titled: "The Gray and Cloudy Present." Click for copy.

Caudill, according to the University of Kentucky archive where his papers are housed, “was best known nationally for his role as a writer… who drew attention to the social, economic, and environmental problems the coal industry had caused in his region, earning him the moniker ‘Upton Sinclair of the coal fields’.”

According to the archive, Caudill wanted the nation to develop a more objective understanding of Appalachia along with a new land ethic. “…He wanted everyone in and outside of Appalachia to feel the urgency of the realization that haunted him: the knowledge of how important it was for the region to get out from under the shadow of coal and stand on its own….”

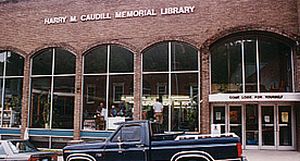

The main public library in Letcher County, Kentucky, located on Main Street in Whitesburg, was named the Harry M. Caudill Memorial Library in 1994. In addition, the Harry Caudill Award for Journalism is made every two years by Bookworm & Silverfish, a book store in Wytheville, Virginia, to recognize investigative journalism in the Appalachian region. In 2010, for example, the $2,000 award was given to journalist Penny Loeb for her book, Moving Mountains, the story of one woman’s battle against the coal industry and mountaintop removal in southern West Virginia.

The Harry M. Caudill Memorial Library, located on Main Street in Whitesburg, KY, was named for Caudill in 1994.

|

Please Support Thank You |

____________________________________

Date Posted: 26 January 2015

Last Update: 22 March 2021

Comments to: jdoyle@pophistorydig.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Mountain Warrior: Harry Caudill, 1950s-1980s,”

PopHistoryDig.com, January 26, 2015.

Title Change:

Jack Doyle, “Harry Caudill, Writer & Activist: 1950s-1980s,”

PopHistoryDig.com, February 4, 2019.

____________________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

Harry & Anne Caudill at their Whitesburg farm, July 1963. |

“Anne and Harry M. Caudill Collection, 1854-1996,” Special Collections and Digital Programs, University of Kentucky Libraries, Lexington, Kentucky.

“The Harry M. Caudill Collection,” Special Collections & Archive, Southern Appalachian Archives, Berea College, Berea, Kentucky.

“Harry Caudill, Southern Appalachian Writers Collection,” Special Collections, D. Hiden Ramsey Library, University of North Carolina, Asheville, North Carolina.

Harry M. Caudill, “The Rape of the Appalachians,” The Atlantic, April 1962.

Harry M. Caudill, Night Comes to the Cumberlands: A Biography of a Depressed Area, Boston: Little, Brown, 1963.

Fred Luigart, Jr., “Compassion for a Region,” Louisville Courier-Journal Magazine, July 7, 1963.

Harriette Simpson Arnow, “A Future As Dark As Coal,” New York Times Book Review, July 21, 1963, p. 184.

Fred W. Luigart, Jr., “Caudill’s in Another Fight,” Louisville Courier-Journal Magazine, November 17, 1963.

“We Are on Our Way to Becoming a Welfare Reservation” (Harry Caudill interview), U. S. News & World Report, May 11, 1964.

Margaret Paschke, “Caudill Urges New Tack on Appalachia,” Kentucky Post, March 17, 1965.

Harry Caudill, “Who Would Wreck a Valley for a Bit of Cheap Fuel.” Mountain Life & Work, Vol. 40, no. 3, Fall 1965 (Remarks before White House Conference on Natural Beauty, May 24, 1965).

Ben A. Franklin, “Strip Coal Mines Vex Kentuckians; 70 Hold Motorcade, Picket Capitol and See Governor, New York Times, June 23, 1965.

“Harry Caudill: God’s Angry Mountaineer,” Appalachian South, Fall and Winter 1965.

David Nevin, “These Murdered Old Mountains – Kentucky Operators are Violently Defacing the Land and Ruining Lives,” Life, January 12, 1968, Photographs by Bob Gomel, pp. 54-64.

David G. McCullough,”The Lonely War of a Good, Angry Man,” American Heritage, December 1969.

Harry M. Caudill, Dark Hills to Westward: The Saga of Jenny Wiley, Boston: Little Brown, 1969.

Jack Trawick, “Strip Mining Foe Keeps Battling,” Winston-Salem Journal and Sentinel, March 22, 1970.

Harry M. Caudill, My Land is Dying, New York: Dutton, 1971.

National Broadcasting Company (NBC-TV), “Harry Caudill Interview with Frank McGee ,” Today Show, January 7, 1972.

“An Interview With Harry Caudill,” Coal Facts, Vol. 1, No. 5, January 28, 1972 (transcript of NBC’s Today Show interview w/Frank McGee ).

Colman McCarthy, “Harry Caudill and His Land,” Washington Post, July 7, 1972.

Donald Felty (Master’s thesis), “Harry Monroe Caudill–A Study in Regional Oratory,” Miami University, Oxford, Ohio, 1972.

J.A.C. Dunn, “Kentucky is a Mix of Violence, Coal and Smiles,” Winston-Salem Journal and Sentinel, September 7, 1974

Harry M. Caudill, The Senator from Slaughter County, Boston: Little Brown, 1974.

Greg Carannante and Jim Webb, “Honorary Mountaineer of the Month: Harry Caudill, Fighter for a Lost Cause?,” Mountain Call, April 1975.

“The Plowboy Interview: Harry Caudill, Appalachian Environmentalist,” Mother Earth News, July/August 1975.

Mary Buckner, “Prophet of Environmental -ists: Kentucky Author Harry Caudill Still Worried About Future,” Lexington Herald-Leader, February 1, 1976.

John Ed Pearce, “Has Harry Caudill Mellowed?,” Louisville Courier Journal & Times Magazine, June 6, 1976.

Harry M. Caudill, The Watches of the Night, Boston: Little, Brown (hardcover, 1st edition), 1976.

Harry M. Caudill, Darkness at Dawn: Appalachian Kentucky and the Future, Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 1976 (on demand paperback).

Scott Payton,” Caudill Looks Back and Ahead as He Takes Leave of His Hills–For Awhile,” Lexington Herald-Leader, August 28, 1977.

W. E. Chilton III and James F. Dent, “Press Essential to ‘Save the Day’,”[Caudill interview] Charleston Gazette-Mail (West Virginia), August 27, 1978.

Kevin Osbourn,”From Politics to Books, Harry Caudill Is Still Thinking,” Kentucky Kernel, April 29, 1980.

Harry M. Caudill, The Mountain, The Miner and The Lord, and Other Tales from a Country Law Office, Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1982.

Lee Mueller, “Harry Caudill Still Beating the Drum for Appalachia,” Lexington Herald-Leader, March 8, 1981.

Elizabeth Rouse, “Harry M. Caudill in His Own Words,” Kentucky Monthly, Vol. 2, No. 5, April 1981.

Alice Cornett, “The ‘Other’ Harry Caudill: A Critique,” Kentucky Coal Journal, April 1981.

“Caudill’s Works Are Filled With Inaccuracies, Hazard Writer Says.” Lexington Herald-Leader, April 19, 1981 [reprint of “The ‘Other’ Harry Caudill: A Critique,” from Kentucky Coal Journal, April 1981; includes a Harry Caudill “Counterpoint.”].

Stephen L. Fischer and J. W. Williamson, “An Interview With Harry Caudill,” Appalachian Journal, Vol. 8, No. 4, Summer 1981.

C. Fraser Smith, “Hulking 6-Footer Drove Home Ugliness of ‘Welfarism’ for Kentucky Muckraker,” Baltimore Sun, November 13, 1981.

Ron Larson, “Appalachia: Tracking the Character of a People Through the Hills” and “Appalachia’s Progressive Destination,” Roanoke Times & World Report, March 28, 1982 and April 4, 1982 [from December 1981 interview].

Ronald D. Eller, “Harry Caudill and the Burden of Mountain Liberalism,” Proceedings of the 5th Annual Appalachian Studies Conference, 1982.

William T. Cornett, “Night Comes to the Cumberlands. Twenty Years After and Twenty Years Ahead,” Troublesome Creek Times, June 30, 1982.

Jim Warren, “Ravages of Strip Mining Still Exist” [Caudill interview], Lexington Herald-Leader, March 7, 1983.

Harry M. Caudill, Theirs Be the Power: The Moguls of Eastern Kentucky, Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1983.

Steve Fisher, “As the World Turns: The Melodrama of Harry Caudill,” Appalachian Journal, Spring 1984 [also a review of Theirs Be The Power].

“We Need Community–But How?”[interview with Caudill and Father Ralph Beiting], Mountain Spirit, November-December 1984.

Katy McCrocklin, “Harry Caudill, Noted Appalachian Author, Leaving UK for Home,” Kentucky Journal, Vol. 1, No. 13, May 2, 1985.

Judy Jones Lewis, “Harry Caudill in Retirement: He Remains a Mountain Rebel,” Lexington Herald-Leader, October 26, 1986.

Harry M. Caudill, Slender is the Thread: Tales from a Country Law Office, Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1987.

Harry Caudill, “The Settling of Eastern Kentucky,” The Mountain Eagle, Wednesday, February3, 1988.

John G. Mitchell,”The Mountain, The Miners, and Mister Caudill,” Audubon, November 1988.

William T. Cornett, “Harry Caudill and Wife Anne Work for Better East Kentucky,” Mountain Eagle, April 12, 1989.

Mary Ellen Elsbernd, “Interview with Anne Frye Caudill,” February and March 1990 [unpublished as of April 1995].

Jim Warren,”Voice of the Mountains,” Lexington Herald-Leader, April 29, 1990.

Mary Ellen Elsbernd and James C. Claypool, “An Interview With Harry Caudill,” Journal of Kentucky Studies, Vol. 7, September 1990.

William T. Cornett, “Mountain Lawyer’s Writings Draw Nation’s Attention to Kentucky Highlands,” Kentucky Explorer, November 1990.

Glenn Fowler, “Harry M. Caudill, 68, Who Told of Appalachian Poverty,” New York Times, December 1, 1990.

Colman McCarthy, “Harry Caudill’s Appalachia,” Washington Post, December 8, 1990.

Tom Gish, “The Man Who Loved the Mountains,” Appalachia, Vol. 24, No.2, Spring 1991.

Loyal Jones,”A Tribute to Harry M. Caudill,” Appalachian Heritage, Vol. 19, no. 2, Spring 1991.

David McCullough. Brave Companions: Portraits in History, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1992.

Thomas T. Ross, “Harry Caudill’s ‘Night Comes to the Cumberlands’ Marks 30th Anniversary,” Kentucky Explorer, September 1993.

“Ups and Downs: Caudill Was Right; A Vote For Tax Equity,” Lexington Herald-Leader, May 28, 1994.

“Appalachia: Hollow Promises,” Special Series, Columbus Dispatch (Ohio), September 1999.

Jedediah Purdy, “Rape of the Appalachians,” The American Prospect, November 14, 2001.

Tylina Jo Mullins, “A ‘Good Angry Man’: Harry Caudill, The Formative Years, 1922-1960,” University of Kentucky Master’s Theses, 2002, Paper 299.

Chad Montrie, To Save The Land and People: A History of Opposition to Surface Coal Mining in Appalachia, University of North Carolina Press: Chapel Hill & London, 2003.

“Harry Monroe Caudill,” University of Kentucky Alumni Association, Lexington, KY.

Ronald D. Eller, Uneven Ground: Appalachia Since 1945, University Press of Kentucky, June 30, 2009, 376 pp.

Jeff Biggers, “‘Rape of the Appalachians’ Turns 50: What Would Harry Caudill Do Today?,”

Huffington Post.com, May 31, 2012.

John Cheves & Bill Estep, “Meet the Man Who Focused the World on Eastern Kentucky’s Woes,” Lexington Herald-Leader, December 16, 2012.

John Cheves & Bill Estep, “The Making of an Angry Book about an Exploited Appalachia,” Lexington Herald-Leader, December 17, 2012.

John Cheves & Bill Estep, “The World Comes to Whitesburg to Take Harry Caudill’s ‘Poverty Tour’,” Lexington Herald-Leader, December 19, 2012.

“Fifty Years of Night: The Story of Eastern Kentucky’s Continued Struggles 50 Years After a Country Lawyer Focused the Nation on its Problems,” Lexington Herald-Leader, December 16, 2012

John Cheves & Bill Estep, “Disillusioned, Harry Caudill Blames ‘Genetic Decline’ in Eastern Kentucky,” Lexington Herald-Leader, December 21, 2012.

John Cheves & Bill Estep, “Harry Caudill Inspired the War on Poverty, but Gloom Darkens His Legacy,” Lexington Herald-Leader, December 23, 2012.

Anne F. Caudill, Op-Ed, “Anne Caudill: Harry Caudill Found Eugenicist’s Plan Dubious,” Lexington Herald-Leader, February 4, 2013.

Anne F. Caudill, Op Ed, “Series Ably Showing E. Ky. Promise, Peril,” Lexington Herald-Leader, August 19, 2013.

George Vecsey, “Anniversaries for Two Other Giants,” GeorgeVecsey.com (Vecsey, a former New York Times reporter who knew Harry Caudill), November 8, 2013.

__________________________________