On March 18, 1967, the oil tanker, Torrey Canyon, one of the world’s early “supertankers”– about three football fields in length and loaded with 121,000 tons of Kuwati crude oil – ran aground in the Atlantic Ocean off Land’s End, at the southwestern tip of England. Over the next 12 days, the entire cargo – estimated between 857,600 and 872,300 barrels – was released into the sea or burned. In spite of a major spill response effort, huge oil slicks formed that polluted British and French coastlines. While one of the first major oil tanker disasters at sea, it occurred at a time when popular environmental consciousness was just beginning to emerge. Still, to this day, the Torrey Canyon oil spill remains the largest in U.K. history.

March 1967. Torrey Canyon, run aground on reef, leaking oil off SW England. |

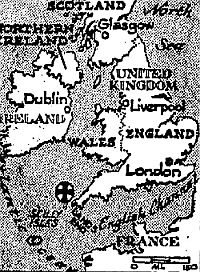

Map showing location of oil spill. |

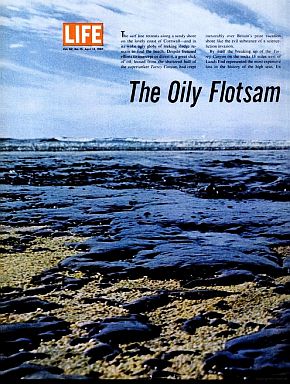

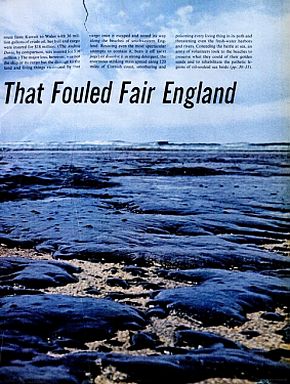

An American story on the spill that appeared in Life magazine on April 14, 1967, would show in one graphic two-page photo (below), how extensive and thick the oil was that was reaching some of the Cornish beaches in England. Also, according to Life, the spill was “threatening even the fresh-water rivers and harbors.” As the Life photos made clear — and others in the British press — the thick deposits of spilled crude would make clean-up a difficult task. But there was much more drama to this disaster at sea as well.

Life magazine story of April 1967 showed thick oil deposits on England’s coastline from tanker spill. |

The spill “spread along 120 miles of Cornish coast, smothering and poisoning every living thing in its path”. |

Originally built in 1959 at Newport News Shipbuilding in Newport News, Virginia with a capacity of 60,000 tons, the Torrey Canyon was later enlarged in Japan, doubling its size to supertanker status. At the time of the spill, it was the 13th largest merchant ship then on the high seas. The ship was owned by American company, Union Oil of California (later responsible for the Santa Barbara oil spill of January 1969). On this trip, the Torrey Canyon was chartered to British Petroleum, whose oil was in its hull.

In February 1967, the Torrey Canyon, with a 36-man Italian crew, had filled its cargo hull with Kuwaiti crude, setting sail from the Middle East on February 19th, 1967 to its destination and delivery point at Milford Haven, Wales, U.K., home to oil refining facilities. Because of its size, the Torrey Canyon could not pass through the Suez Canal, and so its route took it around the southern tip of Africa, then north to the British Isles.

Map showing southwestern tip of England at Land’s End and the offshore Scilly Isles in the Atlantic Ocean.

So, in the course of their travels, as they arrived just south of Land’s End and the Scilly Isles – then off the coast by about 80 miles or so – the captain chose to run a course between Land’s End the Scilly Isles. That area could be tricky for navigation, with known shoals and something of a graveyard for ships venturing there.

As later revealed at a spill inquiry, the captain’s decision to take this route amounted to a short cut, having had the opportunity earlier, to pass west of the Scilly Isles and then travel north-northeast toward Milford Haven.

But the navigational challenge the Torrey Canyon would face, was even narrower than might first seem apparent. For the course the captain took was between the Scilly Isles and the notorious Seven Stones Reef a rocky reef formed by two groups of rocks and is nearly 2 miles long and 1 mile wide (geologically, the reef is believed to have been a now-submerged ancient land bridge that once connected Land’s End with the Scilly Isles).

Atlantic Ocean off Land’s End, showing Scilly Isles and Seven Stones Reef, where the Torrey Canyon grounded.

After the grounding, and over the course of the next several days, unsuccessful attempts were made to tow and float the giant ship off the reef. As a second attempt by the Dutch salvage team was being made to pull the tanker off the rocks, oil vapors from the spill had built up in some segments of the ship. At noon on March 19th, there was an explosion on one part of the ship, with five men injured and two blown into the sea. One died and one was rescued. Initially, the captain and crew of the stricken tanker stayed aboard the vessel during attempts to free it from the reef, but were later taken to safety after those attempts failed.

This photo provides some perspective on how large the Torrey Canyon actually was. It shows a smaller rescue boat on one side of the tanker, boarding crew members from the endangered vessel to take them ashore.

As oil slicks spread away from the wreck, concern on shore in the coastal communities throughout the Cornwall region began to grow. The region was quite popular as a tourist and vacation area, with attractive beaches, coves, and quaint villages. There were fears that the beaches of Cornwall, Devon and Dorset would be hit by the developing oil slicks. There was also concern about the impact on birds, marine life, ocean fisheries, and coastal shellfish (more on these later).

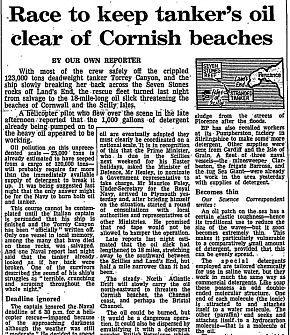

March 20, 1967 headline from “The Guardian” of London: “Race To Keep Tanker’s Oil Clear of Cornish Beaches”. |

“The West Briton & Royal Cornwall Gazette” of March 21, 1967 offered front-page stories on the spill. |

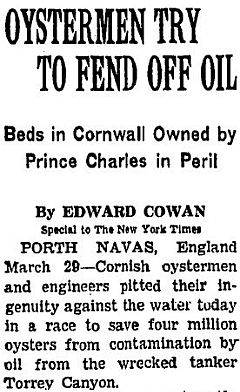

British newspapers, both in London and locally in Cornwall, carried extensive stories on the spill. The Guardian newspaper in London ran a March 20, 1967 story with the headline, “Race To Keep Tanker’s Oil Clear From Cornish Beaches,” which explored the strategies being employed to contain and disperse the spill. Among the local press, headlines in The West Briton and Royal Cornwall Gazette of March 21, 1967, included the following: “Cornwall All Set for The Battle of the Beaches”; “Troops Stand By To Help”; “‘Build Boom To Save Oysters’”; “On The Oil Patrol – Over a Chocolate Sea”; and, “Spray on Regardless The Navy is Told.” In America, too, the New York Times of March 21, 1967, also reported on the early worries of the spill coming ashore, noted with one headline: “British Rush Steps to Disperse Oil Slick Off Coast,” followed by two sub-heads: “Flow From Grounded Tanker Menaces Vacation Beaches,” and “Chemicals Are Sent by Navy to Avert ‘Ruin’ for Resorts.”

The Torrey Canyon supertanker shown breaking up on the Seven Stones Reef, afterwhich it would release more oil into the sea.

After the attempts to move and/or offload oil from the Torrey Canyon failed, the ship began to break up (photo above). More oil leaked into the ocean. Three major oil slicks formed from the time when the vessel grounded – the first, with about 219,900 barrels; another of 146,600 barrels; and a third of 366,500 barrels after the vessel broke apart on March 26th. Some of the slicks would become quite large, one noted at 35 miles long and 15 miles wide in places, and 10 inches thick.

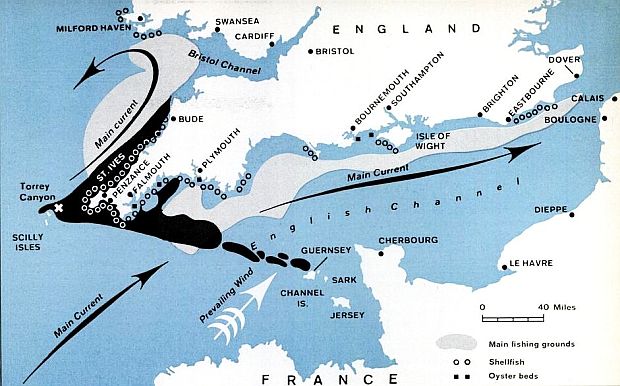

Map appearing in April 1967 edition of Life magazine showing initial extent of spill (would later reach France), also showing fishing areas of concern (in gray), shellfish areas (o o o) and a few oyster beds (black squares).

On March 28, 1967, the New York Times ran a front-page story on the Torrey Canyon oil spill with photo, this one showing the tanker now split apart in three sections. The headline read: “Oil Slick Sweeps Shores of Britain; Big Tanker Splits.” That story also quoted British Navy Minister, Maurice Foley, then dealing with the pollution from the wreck, as saying: “This is a problem no country in the world has had to face before.”

Dispersants

The spill response effort at first had focused on methods of containment, but containment booms were of little use in rough seas. Then attempts to break up the spill with chemical detergent dispersants became a primary strategy. “Dispersants” are chemical agents that are typically mixtures of solvents, surfactants, and additives. In fact, within the first day of the Torrey Canyon spill, the British government gave the go ahead for the use of chemical dispersants (and detergent mixtures) to help break up and disperse the resulting oil slicks.

March 1967. British military assist in dumping copious quantities of chemical dispersant on Cornwall beach areas hit by crude oil spill coming ashore from Torrey Canyon supertanker, run aground on Seven Stones Reef.

The British Navy assisted with transporting the chemicals to the site of the grounding and another 40 or more vessels were chartered for the spraying operation. The dispersants were also used on oiled beaches. Over 10,000 tons were used in the effort. In some cases, 45-gallon drums were rolled to cliff-top edges and poured at will to ‘treat’ inaccessible coves, or dispensed in steady streams from low-hovering helicopters. These dispersants, however, were “first-generation” and largely toxic, later found to be a major factor in the death of birds and marine life (more on the toll later).

In this case, the detergent/dispersant being used was made by British Petroleum, the owner of the oil being spilled from the Torrey Canyon. The BP dispersant, known as “BP 1002”, was sprayed on the oil slicks by various vessels at sea with the intention of emulsifying and dispersing it.

Use of the dispersants, however, was not without risk. The BP version, for example, by one account, was comprised of about 60%-to-70% aromatic solvents, such as benzene, xylene and toluene. Concentrations of 10 parts per million or less of these detergents were known to be acutely toxic to many marine mammals and plants. Oystermen in some areas moved to prevent the use of the dispersants in oyster bed areas (more on dispersant effects later below).

Burning & Bombing

Meanwhile, back on the reef where the Torrey Canyon was impaled and leaking, more drastic measures were soon applied. It became clear that the wreck could not be floated off the rocks, and its growing oil slicks were not dissipating. The likelihood that onshore winds would bring more oil ashore was also a concern. So the British government – following a brief meeting of UK Prime Minister Harold Wilson and some of his cabinet – decided to set the oil slicks and the wrecked vessel on fire with the goal of burning off the oil and scuttling the ship. The plan was to set the fire by way of aerial bombing. On March 28th, 1967, the Royal Air Force began the mission, as its aircraft started dropping 1,000-pound bombs on the ship to help sink it and make the oil blaze. The bombing strategy made front-page news throughout the UK and also in America.

Portion of the front-page of the March 29th, 1967 New York Times, with headline, “Jets Bomb Grounded Tanker Off Cornwall,” with photo of the bombing, along with two stories about the spill below the photo – “Wide Area Of Ocean Aflame as British Burn Off Oil,” and, “Volunteers Work to Rescue Stranded Ocean Birds”.

The New York Times ran a front-page photo of the bombing and its smoky aftermath on March 29, 1967 with the headline, “Jets Bomb Grounded Tanker Off Cornwall.” Two stories about the bombing and the spill also appeared below the photo – “Wide Area Of Ocean Aflame as British Burn Off Oil,” and, “Volunteers Work to Rescue Stranded Ocean Birds.” In London, The Guardian newspaper also ran a front-page story with a similar photo.

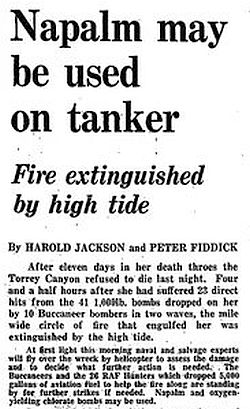

The Guardian newspaper of March 29, 1967 notes possible napalm use on the spill.

However despite the direct hits and a towering inferno of flames and smoke as the oil slicks began to burn, the wrecked tanker refused to sink.

In fact, the bombing mission was called off for the day when high spring tides put out the flames.

Early the next morning, naval and salvage experts flew over the site by helicopter to assess the damage and consider next steps. It was later decided to use napalm and oxygen-yielding chlorate bombs to help re-establish and boost the fire at the wreck site.

Further bombing runs by Royal Navy Sea Vixens and Buccaneers as well as more RAF Hunters unleashed napalm – liquified petroleum jelly – to ignite the oil. A Navy helicopter also dropped napalm, sodium chlorate, and aviation fuel to help feed the fire. Bombing continued into the next day before the Torrey Canyon finally sank.

In the end, over three days of bombing, 161,000 pounds of explosives were dropped on the stricken tanker, along with 16 high-powered rockets, 3,200 gallons of napalm, and 9,800 gallons of kerosene.

Onshore, meanwhile, the effects of the spill were mounting in a number of coastal areas. At Porth Navas, local oystermen had teamed up with engineers in an attempt to save four million oysters from oil contamination. They were working to jerry-rig various kinds of booms, air pressure, and water circulation systems that might help protect their oysterbeds from oil encroaching into tidal areas. Extreme tidal differences then occurring were running as much as 17 feet, completely exposing oyster beds at low tide, making them vulnerable to the clinging oil left behind. Oystermen at the mouth of the River Fal near Penryn and Flushing were also experimenting with a boom-and-skirt device that might help protect their beds.

March 30, 1967. New York Times. |

Torrey Canyon oil sludge being collected by front-end loader. |

Beach communities throughout Cornwall were being hit with major oil pollution on their shores. Among the worst were the beaches of Marazion and Prah Sands, where the oil sludge was up to a foot deep. Front-end loaders and other such heavy-duty equipment were being used on some beaches to scoop up the thick oil sludge. Early reporting had it that up to 70 miles of British beaches were seriously contaminated.

Channel Isles & France

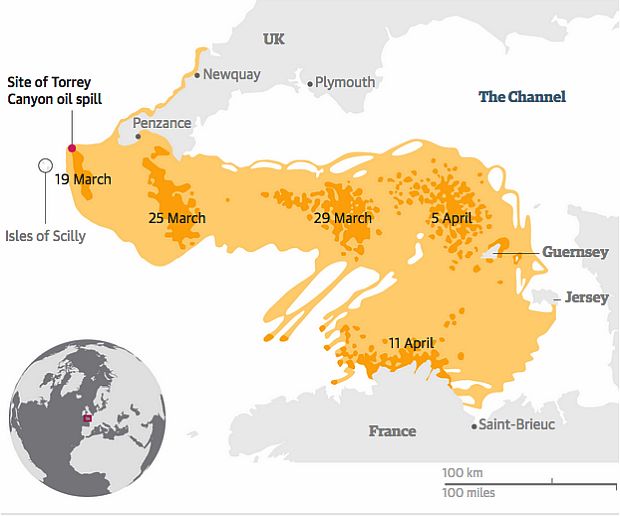

The bombing and burning at the Torrey Canyon wreck site on the Seven Stones Reef did not diminish the oil slicks that had already formed, then coating English beaches and coves in Cornwall and beyond. Through late March and early-to-mid April 1967, the oil was also on the move beyond England, reaching the English Channel and northern France. On April 6th, about nineteen days after the Torrey Canyon had grounded, a huge slick from the spill hit the western shores of Guernsey, an island in the English Channel and quite a popular recreation and tourist destination.

Map showing later stages of Torrey Canyon oil spill, from late March into April 1967, moving into the English Channel, reaching the Channel Islands and north coast of France. Source: The Guardian graphic / Metro France, World Ocean Review.

The first priority on Guernsey island was to get the oil off their beaches. Their plan quickly became one of sucking up the oil – some 3,000 tons of it – into sewage tankers and transporting it to a deep quarry on the island where it would be dumped. Said one, recalling their plan: “…It was, ‘We’ve got to clear our beaches, we’re a tourist destination, right. There’s a quarry, let’s put it there’.” And there is stayed, until 2010 or so, when efforts to clean up that location began.

Photo of quarry on Guernsey island in the English Channel where Torrey Canyon oil spill waste from beach clean-ups was dumped. Photo from 2010, as thereafter clean-up of the waste oil in the quarry was begun.

By April 8th, 1967 the French Navy minesweeper, Betelgeuse, one of many vessels and aircraft then tracking the Torrey Canyon spill, reported that a group of slicks was within five miles of the Brittany coast. Rather than bombing the slick with napalm, or dumping detergents on it, the French used powdered craie de Champagne, a chalky substance which sank the oil more effectively. The French reportedly had more success keeping very large quantities of the offshore oil slicks from reaching their shores. However, there was still an extensive cleanup on French beaches along the northern coast of Brittany. Manual beach recovery operations were organized, and in some locations straw was used to absorb the oil. Still, there was repeated pollution from offshore Torrey Canyon oil on some French shores. In late May 1967, persistent oil slicks off shore would continue to threaten the western shores of Brittany, as offshore winds sent more oil toward the coast. Booms were then erected to protect harbors at Brest, Morgat, Douarnenez and Audierne and nearby beaches. In the end, the French would remove some 4,200 tons of oil waste from their shores. Numerous volunteers and French military were involved in the cleanup. The spill in France also inspired French singer Serge Gainsbourg to write the song, Le Torrey Canyon.

French soldiers were brought in to clean up the oil on the beach at Perros-Guirec, France.

Like Guernsey island, some of the spilled oil from the French coastline was collected and transported to quickly-dug waste pits. And as on Guernsey, it was only decades later – in September 2011 and February 2012, on the Ile d’Er, near Paimpol – that waste pits dug in spring 1967 for Torrey Canyon oil, were finally emptied. Those wastes were burned in a specialized incinerator near Le Havre.

Spill Impacts

In 1967, the Torrey Canyon oil spill was the world’s worst and most costly shipping disaster, and to date, remains the worst oil spill in U.K. history. The Torrey Canyon spill presented a new threat – in terms of scale – never before experienced in that region. Spilled oil in enormous volumes was spread across the coastlines of southwest England, the Channel Islands, and Normandy, France. At least 120 miles of Cornish coast and 50 miles of French coastline were contaminated. As reported in The Guardian of London, parts of Cornwall’s coastline still remained blackened more than 50 years after the spill. Wildlife and ecological impacts were significant as well. Noted the BBC some years later, looking back on the spill: “The effects went on for years, working on organisms from the bottom of the food chain – the plankton and small invertebrates that live in sediments, through mussels and clams on up to fish, birds and mammals.

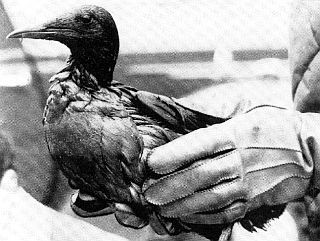

1967. Thousands of Guillemots were among seabirds killed by the Torrey Canyon oil spill, this one at a rescue station.

On the impacted Breton coast of France, breeding pairs of birds had returned from their migration to nest just when the spill had occurred. The Ligue pour la Protection des Oiseaux calculated that there were 450 pairs of razorbills before the spill but only 50 after. For guillemots the number of pairs fell from 270 to 50. It was also estimated by the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds that about 85 percent of puffins on the French coast were also killed. Because of their low reproductive rate, it took several decades for that population to recover.

April 1967. Beach and cove at Whitesand Bay, Cornwall where empty detergent drums then still littered the area.

A 1978 study – eleven years after the spill – found that a species of hermit crab had still not reappeared in one area affected by the spill.

Other marine life in the intertidal zone was also affected, such as limpets, sea anemones, sandhoppers, razorshells, mussels, cockles, crabs and seaweed.

Marine biologists knew that oil could kill 30 percent of rock-shore life such as barnacles and limpets, but the oil was only part of the problem.

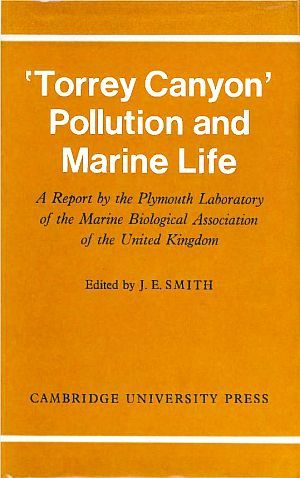

In 1968, the UK Marine Biological Association released its report, “Torrey Canyon Pollution and Marine Life” (Cambridge University Press, 210pp). Click for copy at Amazon.com.

Post-mortem examination results from some birds reported that their lungs were choked with detergent froth. Other damage to wildlife, fisheries and marine organisms also came from the chemical dispersants.

“The detergents made it look good,” explained Dr. Gerald Boalch, a UK marine biologist during a June 2010 interview with The Guardian newspaper.

“We thought at the time it was doing a good job because the oil was disappearing.” But later lab tests and study revealed the actual effects – “and it was realized that it was making the oil more toxic because it was accessible to organisms”.

At sea, the oil was made soluble by the detergents. “It broke up the oil, which helped the tourism industry…,” Boalch explained, “but the oil sank from the top of the waves to the bottom, breaking into smaller parts and being ingested by marine life.” On shore, the chemicals destroyed lichens and other beach-life, he said.

A Marine Biological Association report in 1968 found that UK’s use of detergents resulted “in the death of a large number of shore organisms of many kinds”. It took 13-15 years for the treated areas to recover, about five times longer than those areas where the oil was dispersed naturally by wind and waves.

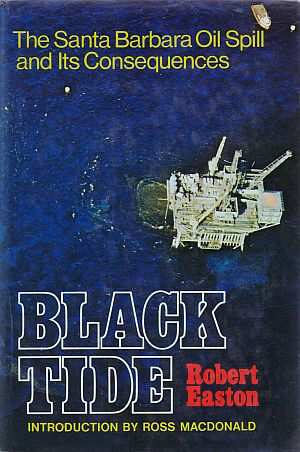

In January 1968, two books were published on the Torrey Canyon disaster. Edward Cowan, who earlier had reported on the spill for the New York Times London bureau, published Oil and Water: The Torrey Canyon Disaster (J. B. Lippincott Co., 241 pp). This book was also published in London the following year (as shown below). Another book, also first issued in January 1968, was Richard Petrow’s In The Wake of Torrey Canyon …The Great Oil Disaster – Its Causes, Consequences and Lessons for the Future (David McKay Co. publishers). A British edition of this book used the title, The Black Tide: In The Wake of Torrey Canyon (Hodder & Stoughton, 256 pp).

In February 1968, a short New York Times review of these books together by reporter Richard Shepard praised both works, noting: “Mr. Petrow shines in the colorful personal touches and Mr. Cowan is a brilliant pilot through the tricky channels of the oil business. Their reportages are thorough, neatly written and intelligently interpreted…” An earlier book – The Wreck of the Torrey Canyon – published in October 1967, and shown below, was also written by two reporters and a naturalist involved with the spill.

Damages & Redress

Oct 1967 UK book, “The Wreck of The Torrey Canyon,” by 2 reporters and a naturalist involved with the spill. Click for copy.

Yet sorting through the web of the ship’s owners and responsible parties, as well as jurisdictional issues (international waters vs. nation-state) and various other legal matters, would prove a challenging gauntlet.

The Torrey Canyon tanker was nominally owned by Barracuda Tanker Corporation, sometimes billed as a subsidiary of Union Oil Co. – more or less a kind of “shell company.” Barracuda was a creation of Dillon Read & Co., investment bankers in New York. In that creation, Dillon Read used funds provided by Manufacturers Trust. Reportedly, stockholders in Barracuda put up $20,000 and were told they would reap $1 million profit in 20 years, subject only to capital-gains tax.

Barracuda’s official address, meanwhile, was Hamilton, Bermuda. The tanker itself was registered in Liberia – an arrangement also known as “a flag of convenience,” considered a pejorative by some for liability avoidance and “lowest-common-denominator” regulation and taxation. Traditionally, a ship is obliged to follow the law of its flag state, while coastal and port states cannot usually impose their laws on a foreign vessel. By being registered in Liberia, the tanker’s owners could not only escape often stricter legal and environmental standards that might be found in coastal or port nations, but also reduce or escape certain taxes.

New York Times news clip, April 3, 1967.

Union Oil, meanwhile, had filed a defensive legal action in September 1967 in Federal Court in New York to limit their liability. Under a U.S. statue at the time, the owner of a vessel could not be liable for damages more than the ship’s salvage value – which for the wrecked Torrey Canyon now on the ocean bottom at Seven Stones Reef, was zero, save a surviving lifeboat worth $50.

But the Court of Appeals also held that the concept of limited liability was applicable only to the owner – Barracuda – and not the charterer, Union Oil. That’s when Union Oil thought a wiser course of action might be to seek negotiations.

By September 1968, the British were ready to go to trial, but that course had risks as well, involving extremely complex issues of how to estimate damages, which country’s laws would apply, and whether international law made tankers liable for pollution damages.

The British had also charged that laws covering ships like the Torrey Canyon were seriously out of date, and in April 1967 was pushing the multi-nation International Maritime Organization (IMO) – a United Nations agency responsible for regulating shipping – to convene a special session to discuss the legal ramifications of maritime oil spills and new regulation.

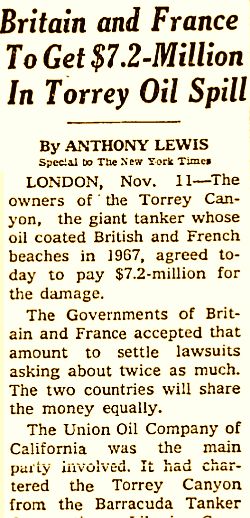

New York Times news clip, November 12, 1969.

Lloyd’s insurance brokers said they believed it was the biggest settlement in marine history for oil claims. Still, the amount was only a portion of all costs related to the Torrey Canyon spill. The two governments had sued the tanker owners for $22 million. But the owners claimed that under maritime law they were liable only for a certain value per ton of the ship’s weight, which would have amounted to $4.2 million.

The settlement amount of $7.2 was split evenly between the two countries, each receiving $3.6 million. The owners also agreed to set aside another $60,000 to compensate any claims from persons not already reimbursed by the governments for their losses. The settlement for the two countries, in any case, was inadequate, representing only a portion of the actual cleanup costs and harms done, and did not include damages to fishermen, resort owners, and other coastal interests – nor adequate in terms of today’s more sophisticated calculations of natural resources damages.

Union Oil, for its part, was also facing other oil spill woes and legal battles for their January 1969 offshore oil rig blow out in the Santa Barbara channel of California.

In the end, the Torrey Canyon accident led to changes in international shipping regulations, brought strict liability to ship owners, and helped pass the 1973 International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships. But implementing those changes would be another battle, especially for international conventions that required nation-state ratifications that could drag out for years. And subsequent spills on the high seas would often entail their own legal battles and/or corporate and nation-state gaming of laws and international conventions.

Spills Continue

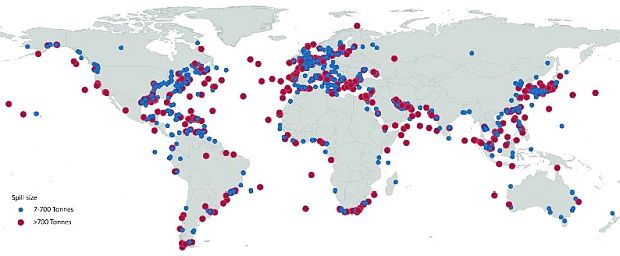

The Torrey Canyon disaster marked the beginning of the “modern era” of oil spills at sea, commencing the “big tanker era,” as well as that of large offshore oil rigs around the world, the latter of which would also have their own share of spills, blowouts, fires and explosions. In fact, about a decade after the Torrey Canyon disaster, nearly in the same general area of the Atlantic Ocean off the English and French coasts, came the sinking of the tanker Amoco Cadiz on March 1978, which spilled 223,000 tons of oil when it ran aground off Brittany. But in fact, legions of spills, large and small, have occurred since the days of the Torrey Canyon, and continue to occur all around the world. The map below, for example, provides a general overview of some of those spills in the 1970-2018 period.

Map shows what is believed to be 90 percent of spills 7 tons or greater. Blue dots = 7 to 700 tons spilled; red dots, spills greater than 700 tons. Source: International Tanker Owners Pollution Federation (ITOPF).

For additional stories at this website under the general topic of “oil and the environment,” see for example: “The Brent Spar Fight: Greenpeace: 1995,” features activist battle and media coverage in the North Sea over controversy for the proposed deep-sea dumping of a huge, floating oil-storage facility; “Deepwater Horizon, Film & Spill,” story about the making of the 2016 Hollywood film on the BP offshore oil rig disaster, plus a recap of the politics, media and corporate maneuvering during the real BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico; “Burning Philadelphia,” about the 1975 Gulf Oil Co. refinery fire in that city; “Santa Barbara Oil Spill” covers the 1969 Union Oil offshore oil well blow-out and pollution of California’s coastline; “Texas City Disaster,” about BP’s 2005 Texas City, TX oil refinery explosion and fire that killed 15 workers and injured another 180; “Barge Explodes in NY,” about a gasoline transport barge docked at an ExxonMobil depot that exploded into a giant fireball in 2003, polluting waterways in the New York city area, shutting down water traffic, and shaking up communities for miles around; “Inferno at Whiting: 1955,” about an eight-day catastrophic Standard Oil/Amoco oil refinery explosion and fire near Chicago; “Oil Fouls Montana,” profiles an oil pipeline leak that fouled the Yellowstone River in January 2015; and, “Pipeline Fireball: Bellingham, WA: 1999,” about a tragic gasoline pipeline explosion and inferno that killed 4 boys and terrorized an urban community.

Thanks for visiting – and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research, writing and continued publication of this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

____________________________________

Date Posted: 15 March 2022

Last Update: 15 March 2022

Comments to: jdoyle@pophistorydig.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Torrey Canyon Spill – Off U.K. 1967,”

PopHistoryDig.com, March 15, 2022.

____________________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

Associated Press, “Huge Tanker in Danger On Rocks Off Britain,” New York Times, Sunday, March 19, 1967, p. 79.

“Race To Keep Tanker’s Oil Clear From Cornish Beaches,” The Guardian (London), March 20, 1967.

Granville Watts, “Ship Gushing Oil, British Struggle to Save Beaches,” Boston Globe, March 20, 1967, p. 1.

W. Granger Blair, “British Rush Steps to Disperse Oil Slick Off Coast; Flow From Grounded Tanker Menaces Vacation Beaches; Chemicals Are Sent by Navy to Avert ‘Ruin’ for Resorts,” New York Times, March 21, 1967.

Julian Mounter, “Detergent on Troubled Waters,” The Times (London), March 21, 1967, p. 12.

“Oil From Grounded Ship Swept By Wind Onto Cornwall Beach,” New York Times, March 25, 1967, pp, 1, 25.

Anthony Tucker, “Unknown Problems of Major Spillage,” The Guardian, March 28, 1967.

“Doomed Tanker Splits in Three,” The Times (London), March 28, 1967, p. 1.

Anthony Lewis, “Oil Slick Sweeps Shores of Britain; Big Tanker Splits,” New York Times, March 28, 1967, pp. 1, 3;

Wener Bamberger, “Risk of Oil Pollution in Seas is Baffling Problem,” New York Times, March 29, 1967, p. 2.

Anthony Lewis, “Wide Area of Ocean Aflame as British Burn Off Oil,” New York Times, March 29, 1967.

“1967: Bombs Rain Down on Torrey Canyon” (reporting from March 29, 1967), “On This Day” / BBC.co.uk.

“Torrey Canyon Oil Spill,” Wikipedia.org.

“Napalm Used in Bombing,” The Times (London) March 30, 1967, p. 1.

Anthony Lewis, “British Jets Drop Bombs, Napalm and Rockets on Stranded Tanker in New Effort to Burn Oil Cargo,” New York Times, March 30, 1967, p. 20.

Edward Cowan, “Oystermen Try to Fend off Oil; Beds in Cornwall Owned by Prince Charles in Peril,” New York Times, March 30, 1967, p. 21

“Britain: All Hands Fight Sticky Invasion,” Los Angeles Times, April 2, 1967, p. K-4.

“Battling the Blob,” Newsweek, April 3, 1967, p. 46.

“Congealed Oil Ruins Cornish Coastline,” Washington Post, April 4, 1967, p. A-20.

Associated Press, “Torrey Canyon Oil Sighted Within 5 Miles of Brittany,” New York Times, April 9, 1967, p. 5.

“Britain’s Great Ghastly Ooze,” Newsweek, April 10, 1967, p. 51.

Associated Press, “Torrey Canyon Oil Appears in France,” New York Times, April 10, 1967, p. 70.

“In the Oily Wake of a Tragedy at Sea,” U.S. News & World Report, April 10, 1967, p. 18.

“The Lawyers’ View,” Newsweek, April 10, 1967, pp. 51-52.

Jim Hicks, “Fair England Fouled By Oil: Despite Spectacular Efforts by the RAF to Burn It At Sea, an Oil Slick From a Stricken Tanker Washes Ashore,” Life, April 14, 1967, pp. 26-32.

Jim Hicks, “The Huge Slick, Spreading With Tide and Current,” Life, April 14, 1967, pp. 33-35.

“200 French Boats Are Mobilized To Fight Torrey Canyon Oil Slick,” New York Times, April 14, 1967, p. 8.

“Insurance: In the Wake of The Torrey Canyon,” Time, April 14, 1967.

A. J. O’ Sullivan & Alison J. Richardson, “The Torrey Canyon Disaster and Intertidal Marine Life,” Nature, April 1967.

“Birds, Fish Victims of Black Tide,” Boston Globe, April 17, 1967, p. 3.

John Parrott, “The Oil Ordeal,” Christian Science Monitor, April 18, 1967, p. 9.

“Death by Oil,” Editorial, Boston Globe, April 21, 1967, p. 38.

Edward Cowan, “Britain Begins Legal Action Over Torrey Canyon; Wrecked Tanker and 2 Sister Ships Named in Claim; Law Puts $3,528,000 Limit on Damage in Oil Slick Case…,” New York Times, May 5, 1967, p.16.

“Oil From Torrey Canyon Fouls French Coast Again,” New York Times, May 22, 1967, p. 34.

Robert Rienow and Leona Train Rienow, “The Oil Around Us,” New York Times Sunday Magazine, June 4, 1967, p.13.

Edward Cowan, “Torrey Canyon’s Sister Ship Held in Singapore; Big Tanker Seized in British Suit Against Owners— $8-Million Bail Asked,” New York Times, July 18, 1967.

Crispin Gill, Frank Booker, and Tony Soper, The Wreck of the Torrey Canyon, Devon, England: David & Charles, Ltd., 1967.

Gregory H. Wierzynski, “Tankers Move the Oil That Moves the World,” Fortune, September 1, 1967.

“A Defensive Complaint Is Filed By Owners of Torrey Canyon,” New York Times, September 20, 1967, p. 93.

“Pollution – The Price of Disaster,” Time, November 21, 1967, p. 59.

Alvin Shuster, “Torrey Canyon Report Decries Use of Detergents,” New York Times, March 17, 1968, p. 16.

Philip Howard, “Little Redress For Victims of Oil,” The Times (London), March 28, 1968, p. 8.

Associated Press, “Shipping Notes: Torrey Canyon; Her Sister Ship Arrested Again in Pollution Case,” New York Times, April 3, 1968.

J. Walsh, “Pollution: The Wake of the Torrey Canyon,” Science, April 12, 1968, pp, 167–169.

J. E. Smith (ed), Torrey Canyon Pollution and Marine Life: A Report by the Plymouth Laboratory of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, Cambridge University Press, 210pp.

R. Petrow, In The Wake of The Torrey Canyon, 1968, New York: David Mackay Co, Inc., 1968. First American Edition. 256 pp

Edward Cowan, Oil and Water: The Torrey Canyon Disaster, J. B. Lippincott Co., 1968, first American edition, 241pp.

U.S. Senate, Congressional Record, November 12, 1969.

Anthony Lewis, “Britain and France To Get $7.2-Million In Torrey Oil Spill; Torrey Canyon Suits Settled; 2 Nations to Get $7.2-Million,” New York Times, November 12, 1969, p. 1.

“Firm Pays Two Nations $7.2 Million for Torrey Canyon’s Oil Damage,” Washington Post, November 12, 1969.

Edward B. Garside, “The Wreck of a Tanker,” Book Review, Oil And Water: The Torrey Canyon Disaster, by Edward Cowan, The New York Times Book Review, November 17, 1968, p. 34.

“The Black Tide,” Time, December 26, 1969, p. 29.

Robert W. Deutsch, “Oil On The Water,” The New Republic, February 28, 1970, p. 10.

Stephen Solomon, “Somebody Fouled Up,” The New Republic, October 31, 1970, p. 22,

“Growing Problems of Oil Spills–Reasons and Remedies,” U.S. News & World Report, February 8, 1971, p. 52.

Craig Vance Wilson, “The Impact of the Torrey Canyon Disaster on Technology and National and International Efforts to Deal with Supertanker Generated Oil Pollution: An Impetus for Change?,” The University of Montana, 1973.

U.S. NOAA, Oil Spill Case Histories, 1967-1991 (Seattle, WA), September 1992, Report No. HMRD 92-11.

Robin Perry, Principal, Robin Perry and Associates, Devon, UK, “Protection of Sensitive Coastal Areas in the United Kingdom – From Torrey Canyon to the New Millenium,” #278, 1999 International Oil Spill Conference.

“Torrey Canyon ‘Lessons Learned’,” BBC.co. uk, March 19, 2007.

Grey Hall, “Torrey Canyon Alerted the World to the Dangers That Lay Ahead,” Professional Mariner.com, March 28, 2007.

“Torrey Canyon,” HelstonHistory.co.uk.

“The Torrey Canyon’s Last Voyage,” Splash Maritime.com.au.

Patrick Barkham, “Oil Spills: Legacy of The Torrey Canyon,” TheGuardian.com, June 24, 2010.

“Torrey Canyon Oil in Guernsey Quarry ‘Nearly’ Removed,” BBC.com, November 17, 2010.

Kathryn Morse, “There Will Be Birds: Images of Oil Disasters in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries,” Journal of American History, Volume 99, Issue 1, June 2012, pp. 124–134.

“Torrey Canyon Oil Spill, Unilever 1967,” YouTube.com, Posted by markdcatlin, February 3, 2017.

Peter Geoffrey Wells (Dalhousie University), “The Iconic Torrey Canyon Oil Spill of 1967 – Marking its Legacy,” Marine Pollution Bulletin, February 2017.

Adam Vaughan, “Torrey Canyon Disaster: The UK’s Worst-Ever Oil Spill 50 Years On,” TheGuardian.com, Mar 18, 2017.

Bethan Bell & Mario Cacciottolo, “Torrey Canyon Oil Spill: The Day the Sea Turned Black,” BBC News/BBC.com, March 17, 2017.

“Torrey Canyon – March 18, 1967: The Mother of the Black Tides,” RobinDesBois.org, March 17, 2017.

Alastair Jamieson,“50 Years After Torrey Canyon Oil Spill, a Unique Record of Nature’s Fightback,” NBCnews.com, April 2, 2017.

The Hon. Justice Steven Rares, “Ships That Changed the Law – The Torrey Canyon Disaster,” FedCourt.gov.au, October 5, 2017.

Tom Gainey, “Torrey Canyon Disaster: Cornwall Remembers Devastating Maritime Oil Spill 51 Years On,” CornwallLive.com, March 18, 2018.

Milton D. Ottensoser, “Fifty Years Since the Brussels Conference on Marine Pollution,” N.Y.U. Environmental Law Journal, 2019.

___________________________________