Paul Newman, one of many notable Hollywood stars who became active on behalf of presidential candidates during 1968's primary & general elections. Life magazine, May 10, 1968.

Yet in the 1960s, the caldron of social issues and political unrest throughout the country, coupled in 1967-68 with an offering of hopeful candidates — especially on the Democratic side — brought both older and newer Hollywood celebrities into the political process like never before. “In no other election,” observed Time magazine in late May 1968, “have so many actors, singers, writers, poets, artists, professional athletes and assorted other celebrities signed up, given out and turned on for the candidates.”

A war was then raging in Vietnam and a military draft was taking the nation’s young to fight it. President Lyndon Johnson had raised U.S. troop strength in Vietnam to 486,000 by the end of 1967. Protests had erupted at a number of colleges and universities. In late October 1967, tens of thousands of demonstrators came to the Pentagon calling for an end to the war. In addition, a growing civil rights movement had pointed up injustice and racism throughout America. Three summers of urban unrest had occurred. Riots in 1967 alone had taken more than 80 lives. In the larger society, a counter culture in music, fashion and values — brought on by the young — was also pushing hard on convention. And all of this, from Vietnam battle scenes to federal troops patrolling U.S. cities, was seen on television as never before. Society seemed to be losing its moorings. And more was yet to come, as further events — some traumatic and others unexpected — would fire the nation to the boiling point. There was little standing on the sidelines; people from all walks of life were taking sides.

From left, Sidney Poitier, Harry Belafonte & Charlton Heston at 1963 Civil Rights march.

Hollywood and the arts community had a long history of political involvement and activism on behalf of presidential candidates, dating at least to the 1920s. Even in the dark days of the 1950s there had been a sizeable swath of Hollywood backing Democrat Adlai Stevenson for his Presidential bids of 1952 and 1956. And in the 1960 election of Jack Kennedy, there was notable support from Frank Sinatra and friends, as well as Kennedy family connections to Hollywood. Others, like singer Pete Seeger, had never stopped their activism, even in the face of political pressure.

By the early 1960s, with the civil rights movement in particular, a new wave actors and singers such as Joan Baez, Harry Belefonte, Marlon Brando, Bob Dylan, Charlton Heston, Sidney Poitier, Paul Newman and others were becoming involved in one way or another. Some lent their name or provided financial support; others joined marches and demonstrations.

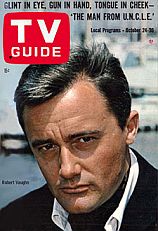

By the mid-1960s, however, the Vietnam War became a goading factor for many in Hollywood. And among the first to speak out and oppose the war was an actor named Robert Vaughn.

The Man from UNCLE

Robert Vaughn was the star of a popular primetime TV spy series called The Man From U.N.C.L.E., which ran from September 1964 to mid-January 1968. Vaughn was among the first to criticize President Lyndon B. Johnson on the Vietnam war — and he did so very publicly in a January 1966 speech. In Indianapolis, at a dinner given to support Johnson’s re-election, Vaughn spoke out against the war and LBJ’s policy there. “Everyone at the front table had hands over their eyes,” Vaughn later explained when asked about the reaction. Vaughn became worried about the Vietnam War after immersing himself in all the documents, books and articles he could find on the subject. “I can talk for six hours about the mistakes we have made,” he told one reporter in 1966. “We have absolutely no reason to be in Vietnam-legal, political or moral.”

In late March 1966, Vaughn went to Washington to meet with politicians. He lunched with Senator Frank Church (D-ID) and also had a lengthy meeting with Senator Wayne Morse (D-OR) to discuss the war. He told the press then “the Hollywood community is very much against” the Vietnam War. “[T]he Hollywood com- munity is very much against” the Vietnam War.

– Robert Vaughn, March 1966.But wasn’t it risky for a star to be so outspoken, he was asked? “I’ve had nothing but encouragement from my friends in the industry, from the studio, even the network,” he said. On his visit to Washington that weekend Vaughn was a house guest of Bobby Kennedy’s at Hickory Hill in nearby Virginia. He continued to be visible in the Vietnam debate, appearing as a guest on William F. Buckley’s TV talk show, Firing Line. He also engaged in impromptu debate with Vice President Hubert Humphrey on a live Minneapolis talk show. At the peak of Vaughn’s popularity, he was asked by the California Democratic Party to oppose fellow actor, Republican Ronald Reagan, then running for California governor in the 1966 election. Vaughn, however, supported Democrat Edmund G. Brown, who lost in a landslide to Reagan.

Vaughn would continue to oppose the war, leading a group called Dissenting Democrats. By early 1968, Vaughn supported the emerging anti-war presidential candidate Senator Eugene McCarthy (D-MN), then running for his party’s nomination. (Vaughn had later planned to switch to Robert Kennedy, a close friend, if Kennedy won the June 1968 California primary).

Gene McCarthy

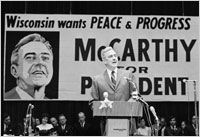

McCarthy at 1968 campaign rally in Wisconsin.

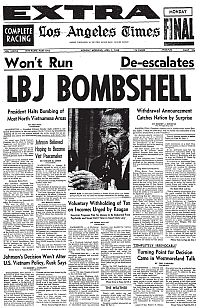

Gene McCarthy had announced his candidacy for the White House on November 30, 1967. Opposing the war was the main issue for McCarthy, who had been prodded to run by anti-war activists. On the Republican side, former vice President Richard Nixon announced his candidacy in January 1968. And on February 8th, Alabama’s Democratic Governor George Wallace — the segregationist who in June 1963 had stood at the doors of the University of Alabama to block integration — entered the presidential race as an Independent.

McCarthy attracted some of the more liberal Democrats in Hollywood, including those who had been for Adlai Stevenson in the 1950s. “…[H]e’s the man who expresses discontent with dignity,” actor Eli Wallach would say of McCarthy in 1968. Wallach had won a Tony Award in 1951 for his role in the Tennessee Williams play The Rose Tattoo and also became famous for his role as Tuco the “ugly” in the 1966 film The Good, the Bad and the Ugly. Wallach liked the fact that McCarthy had taken “a firm position on the war in Vietnam.” Wallach and his wife Anne Jackson, a stage actress, were among those who held fundraisers and poetry readings for McCarthy. Actress Myrna Loy was another McCarthy supporter. She had played opposite William Powell, Clark Gable, Melvyn Douglas, and Tyrone Power in films of the 1930s and 1940s. Loy was a lifelong activist who had supported Adlai Stevenson in 1952 and 1956. In 1968, she became a stalwart for McCarthy, making personal campaign appearances for him and hosting fundraisers. But perhaps the most important Hollywood star to come out for McCarthy was Paul Newman.

Paul Newman Factor

Paul Newman at 1968 fundraiser.

Campaigning by Newman at a McCarthy rally in Menominee Falls, Wisconsin, 1968.

Newman made campaign appearances in New Hampshire during February and March 1968, some with wife Joanne Woodward. Tony Randall and Rod Serling also made appearances for McCarthy in New Hampshire. But it was Newman who drew the crowds and notice by the press. In March 1968, Newman went to Claremont, New Hampshire to campaign for McCarthy. Tony Podesta, then a young MIT student, was Newman’s campaign contact. Podesta worried that day that only a few people might show up to hear Newman. Some credit Paul Newman with raising McCarthy’s visibility in New Hamp- shire, enabling his strong showing there. Instead, more than 2,000 people came out to mob Newman. “I didn’t come here to help Gene McCarthy,” Newman would say to his listeners that day. “I need McCarthy’s help.”

“Until that point,” said Podesta, “McCarthy was some sort of a quack not too many people knew about, but as soon as Paul Newman came to speak for him, he immediately became a national figure.” In New Hampshire, the Manchester Union Leader newspaper published a political cartoon showing Newman being followed by McCarthy with the caption: “Who’s the guy with Paul Newman?” Author Darcy Richardson would later write in A Nation Divided: The Presidential Election of 1968, that Newman’s visit to the state “caused a great stir and drew considerable attention to McCarthy’s candidacy.” New Republic columnist Richard Stout, attributing honesty and conviction to Newman’s New Hampshire campaigning, wrote that the actor “had the star power McCarthy lacked, and imperceptibly was transferring it to the candidate.” Barbara Handman, who ran The Arts & Letters Committee for McCarthy, would later put it more plainly: “Paul turned the tide for McCarthy. . . Paul put him on the map — he [ McCarthy] started getting national coverage by the press. He started being taken seriously.”

New Hampshire Earthquake

On March 12, 1964, McCarthy won 42 percent of the vote in New Hampshire to Lyndon Johnson’s 49 percent, a very strong showing for McCarthy and an embarrassment for Johnson. McCarthy’s campaign now had a new legitimacy and momentum that would have a cascading effect on decisions that both Lyndon Johnson and Bobby Kennedy would make. Paul Newman, meanwhile, continued to campaign for McCarthy beyond New Hampshire and throughout the election year.

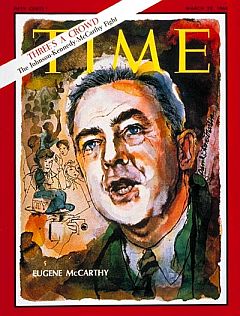

March 22, 1968 edition of Time magazine, reporting on McCarthy’s surprising showing in New Hampshire & the emerging Democratic fight.

Bobby Kennedy, 1968.

Kennedy In, LBJ Out

On March 16th, four days after the New Hampshire primary showed Lyndon Johnson to be vulnerable and McCarthy viable, Bobby Kennedy jumped into the race, angering many McCarthy supporters. Kennedy had agonized over whether to enter the race for months, and in fact, McCarthy and supporters had gone to Kennedy in 1967 to urge him to run. McCarthy then decided to enter the race after it appeared Kennedy was not going to run. But once Kennedy entered the race, he and McCarthy engaged in an increasingly heated and sometimes bitter contest for the nomination.

In 1968, however, party leaders still had a great deal of influence in the nominating process and the selection of delegates. Primaries then were less important and fewer in number than they are today. Still, a strong showing in certain primaries could create a bandwagon effect and show the party establishment that a particular candidate was viable. In 1960, John Kennedy helped get the party’s attention when he defeated Hubert Humphrey in the West Virginia primary. Now in 1968, Gene McCarthy had the party’s attention.

Lyndon Johnson's surprise announcement of March 31, 1968 made headlines across the country.

King shot, April 4, 1968.

King Shot!

On April 4th, 1968, several days after LBJ’s bombshell, the nation was ripped apart by news that civil rights leader Martin Luther King had been assassinated in Memphis, TN. In the next few days, dozens of American cities erupted.

RFK making famous speech in Indianapolis the evening Martin Luther King died. AP Photo/Leroy Patton, Indianapolis News. Click for PBS DVD.

By the end of April, the nation was boiling on other fronts, too. Student protesters at Columbia University in New York City took over the administration building on April 23rd and shut down the campus. On the campaign trail, McCarthy won the April 23rd Pennsylvania primary, and a few days later, on April 27th, Lyndon Johnson’s Vice President, former Minnesota senator Hubert Humphrey, formally announced he would seek the Democratic presidential nomination.

Vice President Hubert Humphrey enters the race for the Democratic nomination, April 1968.

Instead, Humphrey planned to use the “party machine” to gather his delegates and was the favored establishment candidate.

Lyndon Johnson would also help Humphrey, but mostly from behind the scenes since Johnson was regarded a liability for any candidate given his Vietnam record.

Meanwhile, on the campaign trail, a showdown of sorts was brewing between Kennedy and McCarthy as the May 7th Indiana primary approached.

Celebs for McCarthy

In April and early May of 1968, there was a lot of campaigning in Indiana, and star power was again at work with celebrities helping McCarthy. In April, Paul Newman was drawing large crowds in the state for McCarthy, where he made 15 appearances. At one of those stops, Newman explained from a tailgate of station wagon: “I am not a public speaker. I am not a politician. I’m not here because I’m an actor. I’m here because I’ve got six kids. I don’t want it written on my gravestone, ‘He was not part of his times.’ Also making appearances for McCarthy in Indiana were Simon & Garfunkel, Dustin Hoffman, Myrna Loy, and Gary Moore. The times are too critical to be dissenting in your own bathroom.” Newman continued campaigning for McCarthy through May 7 and was then still drawing crowds, with his own motorcade sometimes followed by cars of adoring fans.

Also making appearances for McCarthy in Indiana were actor Dustin Hoffman, singing duo Simon & Garfunkel, Myrna Loy, and TV host Gary Moore. Simon & Garfunkel sang at a McCarthy fundraiser at the Indiana State Fairgrounds Coliseum in May 1968, where Dustin Hoffman introduced them. Hoffman’s popular film at the time, The Graduate — filled with a Simon & Garfunkel soundtrack — was then still in theaters. This celebrity support for McCarthy, as Newman had shown in New Hampshire, was important for McCarthy. “When you have a candidate who is not as well known, and there’s no money so that you can’t by television time,” explained Barbara Handman, head of the Arts and Letters Committee for McCarthy, “these people [celebs] become more and more effective for us. They’re well-known drawing cards…” Handman had previously headed up similar committees for Jack Kennedy in 1960, and Lyndon Johnson in 1964. Her husband, Wynn Handman, was co-founder of the American Palace Theater. Both were well connected in Hollywood.

Celebs for Kennedy

Andy Williams, Robert Kennedy, Perry Como, Ted Kennedy, Eddie Fisher at unspecified 1968 fundraising telethon, Lisner Auditorium, G.W. University, Wash., D.C. (photo, GW University).

Bobby Kennedy campaigning in Indianapolis, May 1968. Behind Kennedy to the right, are NFL football stars Lamar Lundy, Rosey Grier and Deacon Jones. Photo by Bill Eppridge from his book, 'A Time It Was'. Click for book.

Lesley Gore, a pop singer who by then had several Top 40 hits — including “It’s My Party” (1963), “You Don’t Own Me” (1964), “Sunshine, Lollipops & Rainbows” (1965), and “California Nights” (1967) — also became a Kennedy supporter. At 21 years old, and about to graduate from Sarah Lawrence College in Yonkers, New York, Gore became head of Kennedy’s effort to get young voters, called “First Voters for Kennedy.” She volunteered after she heard that Kennedy needed someone to attract young voters. “I understand there are 13 million first-time voters this year,” she told a New York Times reporter in early April 1968. “After my graduation next month I intend to give more of my time to visiting colleges and universities around the country.” In this effort, Gore would be traveling with actresses Candice Bergen and Patty Duke, and also the rock group, Jefferson Airplane.

Andy Williams, a friend and skiing companion to Kennedy, was also a key supporter. “I’m doing it because I think it important,” Williams told a New York Times reporter. “I am worried about the image of America. People don’t think Nixon is swell, and they don’t think Humphrey is swell. Bobby has star quality.” Williams would refurbish his guest house for use by the Kennedy family when Bobby campaigned in California.

Sinatra for Humphrey

Frank Sinatra & Hubert Humphrey, Washington, D.C., May 1968.

During his campaign, Humphrey would gather additional Hollywood and celebrity supporters beyond Sinatra. Among these were some of the older and more established Hollywood names, sports stars, and other leading names, including actress Tallulah Bankhead, opera star Roberta Peters, jazz singer Sarah Vaughan, former heavyweight boxing champ Jack Dempsey, writer and naturalist Joseph Wood Krutch, and fashion designer Mollie Parnis.

Indiana & Beyond

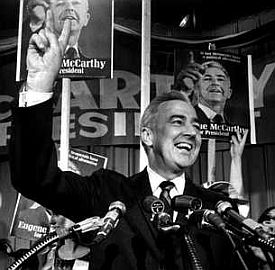

A Gene McCarthy campaign celebration, 1968.

Both candidates campaigned vigorously throughout California, a winner-take-all contest with a large pot of delegates. McCarthy stumped the state’s colleges and universities, where he was recognized for being the first candidate to oppose the war. Kennedy campaigned in the ghettos and barrios of the state’s larger cities, where he was mobbed by enthusiastic supporters. A few days before the election, Kennedy and McCarthy also engaged in a televised debate — considered a draw.

On the east coast, meanwhile, and in New York city in particular, there was a star-studded celebrity fundraising rally for McCarthy in New York’s Madison Square Garden on May 19, 1968. One Canadian blogger, who as a teenager happened to be in New York city that weekend with a friend, recently wrote the following “forty-years-ago” remembrance of the event:

. . .Rob and I did many crazy things that weekend. . . .We learned that McCarthy was having a rally at Madison Square Garden on the Sunday night so along we went figuring we’d meet some more chicks. That event was awe inspiring.

All sorts of famous people spoke or performed that night. Paul Newman, Phil Ochs, Mary Tyler Moore to name a few. A new, young actor said a few words to the crowd on behalf of the candidate. We recognized him as the star of the ‘adult’ movie we had seen the night before. The movie was The Graduate and he was a very young Dustin Hoffman.

Celebrities walked thru the arena imploring people to donate to the campaign. Tony Randall came up our aisle and we gave him a couple of bucks. Stewart Mott (General Motors rich kid) stood up and donated $125,000 right there on the spot. The crowd was delirious. Sen. McCarthy spoke to the crowd and promised to take his fight against Sen. Kennedy all the way to the Chicago convention in August. It was pretty heady stuff for a 17 year-old from Toronto….

RFK campaigning in California.

Robert Kennedy campaigning.

RFK Assassinated!

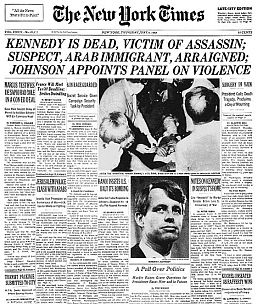

Four hours after the polls closed in California, Kennedy claimed victory as he addressed his campaign supporters just past midnight in the Ambassador Hotel. On his way through the kitchen to exit the hotel, he was mortally wounded by assassin Sirhan Sirhan. His death became yet another of 1968’s convulsing events. Seen as an emerging beacon of hope in a dismal time, many had pinned their hopes on Kennedy and took his loss very personally. The Democratic party went into a tailspin as a stunned nation grieved. Thousands lined the tracks as Kennedy’s funeral train moved from New York City to Washington D.C. Millions watched his funeral on television. At the request of Bobby’s wife, Ethel, Andy Williams sang the “Battle Hymn of the Republic” at Kennedy’s funeral.

New York Times headlines, June 5, 1968.

Historians and journalists have disagreed about Kennedy’s chances for the nomination had he not been assassinated. Michael Beschloss believes it unlikely that Kennedy could have secured the nomination since most of the delegates were then uncommitted and yet to be chosen at the Democratic convention. Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr. and author Jules Witcover have argued that Kennedy’s broad appeal and charisma would have given him the nomination at the convention. And still others add that Kennedy’s experience in his brother’s presidential campaign, plus a potential alliance with Chicago mayor Richard Daley at the Democratic Convention, might have helped him secure the nomination.

Dems Realign

Leading up to Democratic convention in Chicago, former Kennedy supporters tried to sort out what had happened and whether and how they would line up with other candidates. George Plimpton, a well known New Yorker and journalist who authored the 1963 book Paper Lion, had been a Kennedy supporter. He was with Kennedy the night he was assassinated in the Ambassador Hotel kitchen, walking in front of him. In New York, on August 14, 1968, Plimpton sponsored a party at the Cheetah nightclub on behalf of McCarthy supporters, along with co-sponsor William Styron, author of the The Confessions of Nat Turner. Henry Fonda was scheduled to host a McCarthy rally in Houston. “I started out with Senator Kennedy,” explained Fonda to a New York Times reporter, “Now I think McCarthy is the best choice on the horizon.” McCarthy supporters had other rallies and fundraisers scheduled in 24 other cities for mid-August ahead of the Chicago convention, including one at New York’s Madison Square Garden that included conductor Leonard Bernstein and singer Harry Belafonte. Hubert Humphrey’s campaign also had fundraisers, including one in early August at Detroit’s Cobo Hall with performances by Frank Sinatra, Trini Lopez, and comedian Pat Henry.

Humphrey campaign poster.

By mid-August 1968, “Entertainers for Humphrey” included Hollywood names such as Bill Dana, Victor Borge, Alan King, and George Jessel. There were also more than 80 other luminaries in a somewhat less well-known “arts & letters” group including: classical pianist Eugene Istomin, author and scholar Ralph Ellison, violin virtuoso Isaac Stern, manager/impresario Sol Hurok, playwright Sidney Kingsley, opera singer Robert Merrill, authors John Steinbeck, James T. Farrel, and Herman Wouk, and dancer Carmen de Lavallade. Humphrey had also picked up some former supporters of Republican Nelson Rockefeller, including architect Philip Johnson and dancer Maria Tallchief. But Humphrey’s biggest challenges were directly ahead at the Democratic National Convention.

1968: National Guardsmen at the Conrad Hilton Hotel at DNC in Chicago.

Turmoil in Chicago

As the 1968 Democratic National Convention opened in Chicago on August 26, 1968, there was a fractured party and little agreement on the main platform issue, the Vietnam War. In addition to the formal business of the presidential nomination inside the convention hall, there was a huge focus on the convention location as a protest venue for the Vietnam War. Thousands of young activists had come to Chicago. But Chicago’s Democratic Mayor Richard J. Daley — also the political boss running the convention — had prepared for anything, and had the Chicago police and the National Guard ready for action. Tensions soon came to a head.

Convention floor, 1968.

At the convention itself, Chicago mayor Richard Daley was blamed for the police clubbings in the streets. Daley at one point was seen on television angrily cursing Senator Abraham Ribicoff of Connecticut, who had made a speech denouncing the excesses of the Chicago police (this scene shown later below on book cover in Sources). Inside the hall, CBS News reporter Dan Rather was attacked on the floor of the convention while covering the proceedings.

Haynes Johnson, a veteran political reporter who covered the convention for the Washington Post, would write some year later in Smithsonian magazine:

“The 1968 Chicago convention became a lacerating event, a distillation of a year of heartbreak, assassinations, riots and a breakdown in law and order that made it seem as if the country were coming apart. In its psychic impact, and its long-term political consequences, it eclipsed any other such convention in American history, destroying faith in politicians, in the political system, in the country and in its institutions. No one who was there, or who watched it on television, could escape the memory of what took place before their eyes.”

1968: Paul Newman & Arthur Miller on the convention floor.

ABC News of August 28, 1968, for example, included short interviews with Paul Newman, Tony Randall, Gore Vidal, and Shirley MacLaine. Sonny Bono — of the famed “Sonny & Cher” rock star duo — had come to Chicago to propose a plank in the Democratic platform for a commission to look into the generation gap, or as he saw it, the potential problem of “duel society.” Bono, then 28, would become a Republican Congressman in the 1990s. Dinah Shore made a brief convention appearance for McCarthy, singing her famous “See The USA in Your Chevrolet” anthem, adapting it as, “Save The USA, the McCarthy Way, America is the Greatest Land of All,” throwing her trademarked big kiss at the end.

The Nomination

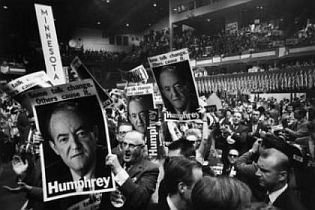

Humphrey supporters, 1968 Democratic National Convention.

Humphrey, for his part, attempted to reach out to Hollywood celebrities, as California would be a crucial state in the general election. Humphrey met with a number of celebrities during and after the convention, one of whom was Warren Beatty. Beatty in 1967 had directed and starred in the movie Bonnie & Clyde, a huge box office hit. Beatty had appeared in a number of earlier films as well, from Splendor in the Grass (1961) to Kaleidoscope (1966). Beatty reportedly offered to make a campaign film for Humphrey if he would agree to denounce the war in Vietnam, which Humphrey would not do. During September and October 1968, a number of Hollywood’s stars and celebrities came around to support Humphrey, with gala events and/or rallies such as one at the Lincoln Center for Performing Arts in New York in late September, and another at the Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles in late October.

Hollywood actor E.G. Marshall narrated a political ad for Hubert Humphrey in 1968 that pointedly raised doubts about opponents Nixon and Wallace. Click to view video.

New York Times, 7 Nov 1968.

Nixon Wins

On November 5th in one of the closest elections in U.S. history, Nixon beat Humphrey by a slim margin. Although Nixon took 302 electoral votes to Humphrey’s 191, the popular vote was extremely close: Nixon at 31,375,000 to 31,125,000 for Humphrey, or 43.4 percent to 43.1 percent.

Third party candidate George Wallace was a key factor in the race, taking more votes from Humphrey than Nixon, especially in the south and among union and working class voters in the north. Nearly 10 million votes were cast for Wallace, some 13.5 percent of the popular vote. He won five southern states and took 45 electoral votes. Democrats did retain control of the House and Senate, but the country was now headed in a more conservative direction.

In the wake of their loss, the Democrats also reformed their presidential nominating process. As Kennedy and McCarthy supporters gained more power within the party, changes were adopted for the 1972 convention making the nominating process more democratic and raising the role of primary elections. Hubert Humphrey would become the last nominee of either major party to win the nomination without having to compete directly in primary elections.

Celebrity Postscript

Many of the celebrities who worked for Democratic candidates in 1968 did not throw in the towel after that election. They came back in subsequent presidential election cycles to work for and support other Democrats ranging from George McGovern and Jimmy Carter to Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama.

And some of 1968’s activists, and their successors, also continued to use Hollywood film-making to probe American politics as film subject. Among some of the post-1968 films that explored politics, for example, were: The Candidate (1972, with Robert Redford, screenplay by Jeremy Larner, a Gene McCarthy speechwriter); All the President’s Men (1976, with Dustin Hoffman and Robert Redford); Wag The Dog, (1997, with Dustin Hoffman and Robert De Niro), Bullworth (1998, produced & directed by Warren Beatty who also plays the central character), and others.

And certainly by 1968, if not before, it had become clear that Hollywood and politics were intersecting in an increasing number of ways, especially in the packaging of candidates. Hollywood experience, in fact, was becoming a political asset for those who decided to run for office. By the mid-1960s, Hollywood actors and TV personalities like Ronald Reagan and George Murphy were winning elections — Murphy taking a U.S. Senate seat as a California Republican in 1964, and Reagan elected in 1966 as California’s Republican Governor. Certainly by 1968, if not before, it had become clear that Hollywood and politics were intersecting in an increasing number of ways. Reagan, of course, would become president in 1980, and others from Hollywood, such as Warren Beatty, would also consider running for the White House in later years.

Today, celebrities and Hollywood stars remain sought-after participants in elections and political causes of all kinds. Their money and endorsements are key factors as well. Yet polling experts and political pundits continue to debate the impact of celebrities on election outcomes, and many doubt their ability to sway voters. Still, in 1968, celebrity involvement was a factor and did affect the course of events, as every political candidate at that time sought the help of Hollywood stars and other famous names to advance their respective campaigns.

See also at this website the related story on the Republicans and Richard Nixon in 1968, and also other politics stories, including: “Barack & Bruce” (Bruce Springsteen & others campaigning for Barack Obama in 2008 & 2012); “The Jack Pack” (Frank Sinatra & his Rat Pack in John F. Kennedy’s 1960 campaign); “I’m A Dole Man”( popular music in Bob Dole’s 1996 Presidential campaign); and generally, the “Politics & Culture” category page. Thanks for visiting – and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research and writing at this website. Thank you. — Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

___________________________________

Date Posted: 14 August 2008

Last Update: 16 March 2020

Comments to: jdoyle@pophistorydig.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “1968 Presidential Race, Democrats,”

PopHistoryDig.com, August 14, 2008.

_________________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

“The D.O.V.E. from U.N.C.L.E.,” Time, Friday, April 1, 1966.

Peter Bart, “Vaughn: The Vietnik from U.N.C.L.E.,” New York Times, May 29, 1966, p. D-9.

Warren Weaver, “M’Carthy Gets About 40%, Johnson and Nixon on Top in New Hampshire Voting; Rockefeller Lags,” The New York Times, Wednesday, March 13, 1968, p. 1.

“Unforeseen Eugene,” Time, Friday, March. 22, 1968.

‘The Hustler’ Is on Cue for McCarthy,” Washington Post-Times Herald, March 23, 1968, p. A-2.

E. W. Kenworthy, “Paul Newman Drawing Crowds In McCarthy Indiana Campaign,” New York Times, Monday, April 22, 1968, p.19

Louis Calta, “Entertainers Join Cast of Political Hopefuls; They Get Into Act to Back 3 Candidates for the Presidency,” New York Times, Saturday, April 6, 1968, p. 42.

Associated Press, “Celebrities Endorse Candidates,” Daily Collegian (State College, PA), May 5, 1968.

Lawrence E. Davies, “Sinatra Supports Slate Competing With Kennedy’s,” New York Times, Sunday, May 5, 1968, p. 42

“The Stars Leap Into Politics,” Life, May 10, 1968.

Leroy F. Aarons, “Poetry’s Popular At Club Eugene,” The Washington Post, Times Herald, May 16, 1968, p. A-20.

“The Pulchritude-Intellect Input,” Time, Friday, May 31, 1968.

“Newman and Miller Named Delegates to Convention,” New York Times, Wednesday July 10, 1968, p. 43.

“HHH Office Unit Opens, With Sinatra,” Washington Post, Times Herald, August 2, 1968, p. A-2.

Richard F. Shepard, “Stage and Literary Names Enlist for Candidates; Plimpton Giving a Party in Night Club to Further McCarthy’s Cause,” New York Times, Wednesday, August 14, 1968, p.40.

Florabel Muir, “Trini Goes All Out for HHH,” The Washington Post, Times Herald, August 15, 1968, p. D-21.

Dave Smith, “Singer to Tell Democrats of Youth’s Views,” Los Angeles Times, Aug 23, 1968, p. 27.

Victor S. Navasky, “Report on The Candidate Named Humphrey,” New York Times Magazine, Sunday August 25, 1968, p. 22.

“Guests Flock to Week-Long Party Given by Playboy…” New York Times, August 29, 1968.

Jack Gould, ” TV: A Chilling Spectacle in Chicago; Delegates See Tapes of Clashes in the Streets,” New York Times, Thursday August 29, 1968, p. 71.

Tom Wicker, “Humphrey Nominated on the First Ballot After His Plank on Vietnam is Approved; Police Battle Demonstrators in Streets,”New York Times, August 30, 1968.

David S. Broder, “Hangover in Chicago – Democrats Awake to a Party in Ruins,”The Washington Post, Times Herald, August 30, 1968 p. A-1.

“Dementia in the Second City,” Time, Friday, September 6, 1968.

“The Man Who Would Recapture Youth,” Friday, Time, September 6, 1968.

“Dissidents’ Dilemma,” Time, Friday, September 20, 1968.

Richard L. Coe, “Candidates By Starlight,” The Washington Post, Times Herald, November 3, 1968, p. K-1.

E.G. Marshall, 1968 T.V. ad for Humphrey Campaign, “Nixon vs. Humphrey vs. Wallace,” @ The Living Room Candidate.org.

Joe McGinniss, The Selling of the President, New York: Trident Press, 1969.

Pope Brock, “Myrna Loy: So Perfect in Her Way, it Almost Seems We Imagined Her,” People, April 4, 1988, p. 47.

Charles Kaiser, 1968 In America: Music, Politics, Chaos, Counterculture, New York: Grove Press, 1997, 336pp.

Ted Johnson (managing editor, Variety magazine), “Paul Newman: Bush is America’s ‘Biggest Internal Threat’,”Wilshire & Washington.com, June 26, 2007.

Ted Johnson, “Flashback to 1968,” Wilshire & Washington.com, April 25, 2008 (also ran in Variety magazine; Ted Johnson is managing editor).

Darcy G. Richardson, A Nation Divided: The 1968 Presidential Campaign, iUniverse, Inc., 2002, 532pp.

Tom Brokaw, Boom! Voice of the 1960s: Personal Reflections on the ‘60s and Today, New York: Random House, 2007, 662 pp.

“Robert Vaughn,” Wikipedia.org.

Ron Brownstein, The Power and The Glitter, New York: Knopf Publishing Group, December 1990 448 pp.

Joseph A. Palermo, “Here’s What RFK Did in California in 1968,” Huffington Post.com, January 10, 2008.

Joseph A. Palermo, In His Own Right: The Political Odyssey of Senator Robert F. Kennedy, New York: Columbia, 2001.

Associated Press, AP Photos @ www.daylife .com.

Ray E. Boomhower, “When Indiana Mattered – Book Examines Robert Kennedy’s Historic 1968 Primary Victory,” The Journal-Gazette, March 30, 2008.

“Forty Years Ago This Weekend – May, 1968….,”BlogChrisGillett.ca, Sunday, May 18, 2008.

Haynes Johnson, “1968 Democratic Convention: The Bosses Strike Back,” Smithsonian magazine and Smithsonian.com, August 2008.

“Democratic National Convention,” Wikipedia .org.

“United States Presidential Election, 1968,” Wikipedia.org.

See also, “The 1968 Exhibit,” a traveling and online exhibit organized by the Minnesota History Center partnership with the Atlanta History Center, the Chicago History Museum and the Oakland Museum of California.

______________________________