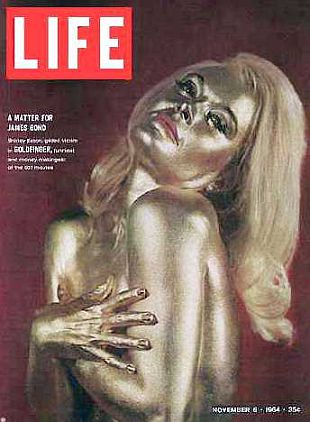

Nov. 6, 1964 cover of Life magazine with actress Shirley Eaton as the gold-painted victim from “Goldfinger” film, with cover story tag line, “A Matter for James Bond.” Click for magazine.

The Bond films, produced by British filmmaker EON Productions, were based on the novels of British writer, Ian Fleming, a WWII-era Royal Navy intelligence officer. Fleming penned the famous spy novels in the 1950s and early 1960s. His first “Bond book,” Casino Royale, published in 1953, introduced the James Bond character, also known by his code name, “007.” More Bond books followed, as did films, making for a famous series of both.

In all, Fleming wrote a dozen Bond books between 1953 and 1966, among them: Live and Let Die (1954), Moonraker (1955), Diamonds Are Forever (1956), From Russia with Love (1957), Dr. No (1958), Goldfinger (1959), For Your Eyes Only (short story collection, 1960), Thunderball (1961), The Spy Who Loved Me (1962), On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1963), You Only Live Twice (1964), and The Man with the Golden Gun (1965). There were also two additional collections of short stories: Octopussy and The Living Daylights published in 1966. Fleming died from a heart attack at the age of 56 in 1964, so two of his Bond books and the collections were published posthumously. Since then, other authors have produced additional Bond novels and there have been more than 25 Bond films. The James Bond entertainment empire has become one of the world’s most valuable, with its books, films, and music continuing to sell to the present day.

Initially, Ian Fleming’s James Bond novels were not bestsellers in America. In the U.K., Fleming’s books enjoyed a popular following and mostly positive reviews through the 1950s – especially his first five books: Casino Royale, Live and Let Die, Moonraker, Diamonds Are Forever and From Russia, with Love. But beginning around March 1958, about the time Dr. No was published, he began to receive some unfavorable reviews from book critics, one saying his Bond books suffered from “the total lack of any ethical frame of reference.” Another review of Dr. No in the New Statesman was titled “Sex, Snobbery and Sadism,” with the reviewer calling it “the nastiest book I have ever read.” For a time thereafter, Fleming fell into disfavor. But his fortunes would soon change and his work would rise once again, receiving a major boost from America.

In early 1961, after one of Fleming’s Bond books was mentioned by Life magazine’s White House reporter Hugh Sidey in an article about President John F. Kennedy’s reading habits, sales of all Fleming’s novels took off in America. Sidey’s article in the March 17, 1961 issue of Life had listed Fleming’s From Russia With Love as one of Kennedy’s ten favorite books. Sidey’s piece also mentioned that the President had invited Fleming to the White House for dinner.

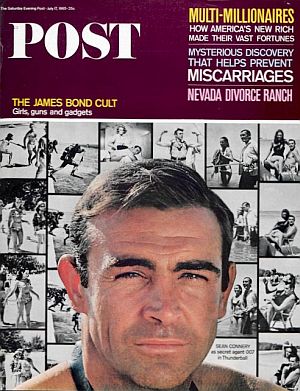

Sean Connery, cast as James Bond in the early Bond films, is shown here in a scene from the 1962 film, “Dr. No.” Connery set the mold for other Bonds to follow.

Connery’s depiction of Bond in the early films, in fact, would have some effect on the character Fleming was continuing to create in his books.

In the novel You Only Live Twice, which Fleming crafted after the Dr. No film, Fleming began to give the Bond character a sense of humor and some Scottish background, qualities that had not appeared in the earlier Bond stories.

The Bond films, in any case, sent Fleming’s books and the entire James Bond enterprise in a wholly new and more prosperous direction. Although the first film, Dr. No, received a mixed reception at its U.K. premiere in October 1962, it still became a popular film at the U.K. box office, and was later released in the U.S. Dr. No, which cost $1 million to make, grossed about $60 million worldwide ($152 million adjusted gross), so the filmmakers knew they had a good thing going. From Russia, With Love, the next film in the series, came out in 1963, and this film did even better, earning more than $78 million ($214 million, adjusted).

But the James Bond mania in the U.S. really didn’t take hold in a big way until 1964-65, with the release of the Goldfinger film. This film also had a notable soundtrack and “Goldfinger” theme song by Welsh singer Shirley Bassey that added to its lustre and marketing (more on the music later). The plot of the Goldfinger story, for book and film, focus on arch villain named Auric Goldfinger, who schemes to play havoc with the world’s finances by messing with the U.S. gold reserves at the Fort Knox bullion depository in Kentucky.

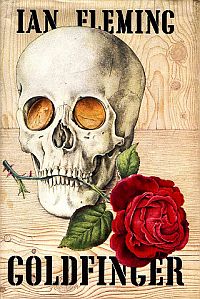

The Goldfinger book was the seventh novel in Fleming’s James Bond series. It was first published by the U.K. publisher Jonathan Cape, Ltd in London in late March 1959, although Fleming had written it a year or so earlier. The cover of the original hardback edition, shown above, featured a skeleton of a human skull with gold coins placed in the eye sockets. The book did reasonably well in the U.K, where Fleming already had millions of readers. Although when it was released in the U.S. in August 1959 by MacMillan – prior to the 1961 JFK boost of the Fleming books – it had not done well. But there were much better days ahead.

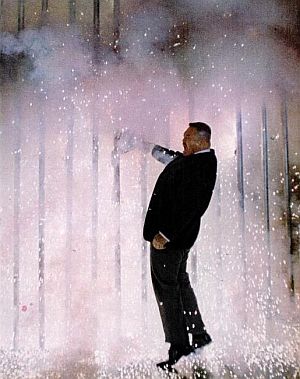

Premiere of the James Bond “Goldfinger” film in New York, Dec.1964.

The American premiere was held on December 21st, 1964 at the DeMille Theater in New York City. To promote the film, the two Aston Martin DB5 sports cars were also showcased at the 1964 New York World’s Fair, as the car and its gadgets became something of star in the film as well. Two of the sports cars can also be seen on the street in front of the theater in the premiere photo above. Following the opening at the DeMille Theater, demand for the film was so high that the theater stayed open twenty-four hours a day for around-the-clock showings from Christmas Eve straight through until after New Year’s Day.

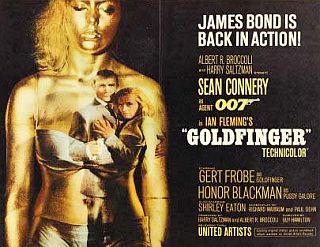

Theatrical poster advertising the “Goldfinger” film.

Goldfinger was both a critical and financial success. Its $3 million budget was recouped within two weeks of its release, and it broke box office records in multiple countries around the world. At the time, it was the fastest grossing film ever. In its original worldwide theatrical release in 1964-65, Goldfinger pulled in $124.9 million. In today’s dollars that would translate to almost $900 million. As one point of comparison, as of April 2009 the Bond film Quantum of Solace pulled in some $576 million worldwide.

Goldfinger’s success led to a variety of product tie-ins for clothing, dress shoes, action figures, board games, jigsaw puzzles, lunch boxes, toys, record albums, and trading cards. Toy manufacturer, Corgi Toys began a long relationship with the Bond franchise, producing a toy car which became the biggest selling toy of 1964. And sales of real Aston Martin sports cars rose as well, partly attributed to the film’s use of the car.

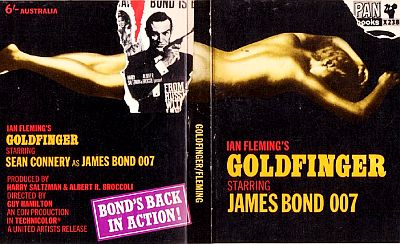

Pan Books paperback edition of “Goldfinger” in Australia used a Sean Connery / James Bond image and movie information on its back cover.

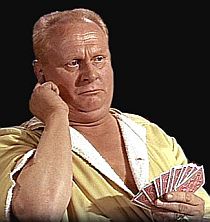

Auric Goldfinger listening to tips on his cheating hotline from balcony overlooking card game in his first unhappy encounter w/James Bond.

In the opening scenes of the Goldfinger film, James Bond is shown on a prior assignment – infiltrating and destroying the house of a drug lord in Mexico. The story quickly segues to his next assignment, as Bond is in Miami Beach, enjoying a bit of R & R, though his holiday is interrupted by agent Felix with orders from “M” in London that Bond should keep his eye on a character named Auric Goldfinger, who as it happened, was also in Miami. Mr. Goldfinger is ostensibly a horse-breeder and international jeweler – and of course, much more. London suspects him of being a gold smuggler, and as soon becomes clear, he is a scheming bad actor.

In Miami, poolside, at the hotel where they are staying, Bond discovers that Goldfinger is cheating in a card game he is playing with another businessman. Bond notices an earpiece, which Goldfinger claims is a hearing aid. But Bond suspects something else and notices a hotel balcony several stories up within Goldfinger’s line of sight.

James Bond, taking in the “card game” view from the hotel balcony with Jill, who is helping Goldfinger cheat. |

Jill is later murdered by Goldfinger with gold paint. |

Oddjob, Goldfinger’s man-servant, is about to decapitate a statue with a throw of his steel-brimmed derby. |

Goldfinger tells James Bond he is about to die by way of an industrial laser slicing him in two, but Bond gains a reprieve by letting on he knows more than he does. |

Ms. Pussy Galore (Honor Blackman), heads up female flyers who will dispense poison gas over Fort Knox. |

James Bond being knocked around by Oddjob during their tussle at the Fort Knox vault. |

Oddjob is electrocuted when his stuck steel-brimmed derby is electrically charged by a wire Bond has thrown. |

Mr. Goldfinger has his revolver trained on Bond while the plane is being hi-jacked. |

In the end, James Bond has saved the day, ending up safely on earth with Ms. Galore. |

Upon closer inspection of the hotel balcony, Bond discovers a beautiful blond in a bathing suit on a chaise longue off one of the balcony rooms – Goldfinger’s room, it turns out. She is on duty there, working for Goldfinger with a pair of high-powered spyglasses relaying to Goldfinger’s “hearing aid” the cards his opponent is holding. Bond spoils the party, ending the card-cheating transmissions, leaving Goldfinger to fend for himself.

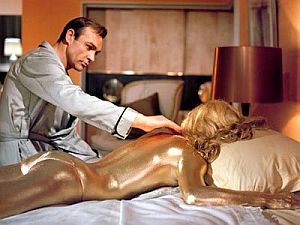

Meanwhile Bond strikes up a relationship with his new found lady friend, Jill, the Goldfinger girl played by Shirley Eaton. The two adjourn to Bond’s hotel room where they share some champagne and romance.

But after Bond leaves the room for a moment to retrieve another bottle of champagne from the suite’s kitchen, he is knocked out by an intruder.

When he awakens, he finds his new girl friend is sprawled across the bed, but painted head to toe in gold paint. She is dead; asphyxiated by the paint. Goldfinger has had his revenge, posting a warning to Bond in the process.

Bond then returns to London where he is assigned to find out how Goldfinger transports his gold internationally, which takes him to Geneva, Switzerland, where he infiltrates Auric Enterprises.

In Geneva, Bond learns that Goldfinger smuggles gold by incorporating it into the body of his automobile, a gold-plated Rolls Royce. Bond also begins to learn that Goldfinger has something else planned: something called Operation Grand Slam.

In Geneva, Bond also meets the sister of the slain Goldfinger girl from Miami who tries to kill Goldfinger, but is herself murdered by Goldfinger’s bodyguard, Oddjob, who has a steel-brimmed derby he throws around as a killing device.

Bond becomes Goldfinger’s prisoner, and he is flown to the States by Goldfinger’s personal pilot, Ms. Pussy Galore, who also heads up a group of female aviators who later figure into the Goldfinger plot.

Bond is taken to the Auric Stud Farm in Kentucky where he further learns of Goldfinger’s plans. Goldfinger at one point tries to slice Bond in half with a deadly industrial laser, but Bond talks his way out of it, claiming that London would suspect the worst if he were dead and foil Goldfinger’s plans.

At the Kentucky horse farm, Goldfinger has a meeting with several mob leaders from across America. Goldfinger owes each of them one million in gold, which he promises to increase if they go along with his latest plan for Fort Knox.

However, one of the mob leaders disagrees, and Goldfinger, seemingly, pays him his gold bullion and allows him to leave. Oddjob then appears to be taking the disgruntled mob boss to the airport, but instead, the mobster ends up murdered in car-crushing junkyard where he and his car are reduced to a small cube.

Back at the horse farm, Goldfinger gasses the other mob leaders believing them a risk to his plan, also cancelling out his mob debt. The mobsters are gassed in the self-sealing briefing room.

Meanwhile, Bond has learned that Operation Grand Slam will be an attempt to irradiate the U.S. gold supply at Fort Knox, making the gold radioactive for decades, thereby increasing the value of Goldfinger’s holdings while plunging the U.S. into economic chaos.

Goldfinger’s personal pilot, aviatrix Pussy Galore and her “Flying Circus” of female flyers, will take their planes over the Fort Knox area on the appointed day, spraying lethal gas to take out the military. Goldfinger and his forces will then helicopter in with their dirty bomb for the Fort Knox vault.

Bond, however, has won the affections of Ms. Galore, and she substitutes a harmless gas for the aerial spray while informing U.S. authorities of Goldfinger’s sinister plot.

Still, at the Ft. Knox vault during Goldfinger’s raid, Bond must deal with the bomb, now installed and ticking away, and also with Oddjob, who is out to kill him.

Bond and Oddjob struggle in a dramatic fight, with Oddjob electrocuted in a final scene when he tries to retrieve his steel-brimmed hat which had become stuck in the metal bars of the repository from an earlier throw. As Oddjob grabs the hat on the metal bars, Bond throws a live electrical wire on the bars charging them with current and doing in Mr. Oddjob.

Mr. Goldfinger, meanwhile, has dressed in a colonel’s uniform beneath his regular clothes, and is able to use this disguise in a last minute maneuver to kill the U.S. troops attempting to open the vault, while then escaping the scene himself. A bomb expert arrives, meanwhile, and manages to stop the dirty bomb clock at 0:07 seconds remaining.

With the Fort Knox threat foiled, and the gold supply safe for the moment, Bond is invited to the White House for a meeting with the President. He is squired to Washington aboard an Air Force jet, and all appears well.

However, on the way to Washington the plane is hijacked by Goldfinger, who has disguised himself as a U. S. general and has coerced Pussy Galore to pilot and divert the jet to Cuba.

In the plane, a struggle ensues over Goldfinger’s revolver, and in the course of their fight, one of the plane’s windows is shot out, creating a decompression in which Goldfinger is sucked out of the cabin to his death.

As the plane tailspins toward earth and out of control, Bond rescues Ms. Galore and the two parachute safely to the ground below, where they become reacquainted as the film ends and the film score plays.

The Music

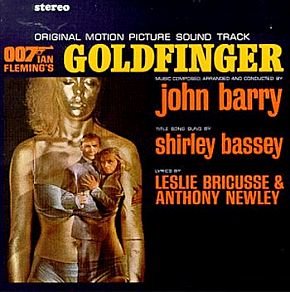

Goldfinger was made especially memorable for many film goers by way of its music. For the first time in a Bond movie, a theme song was sung over the opening credits. And in this case, the song was “Goldfinger,” performed in brassy fashion by Welsh singer Shirley Bassey. The song was a most powerful addition to the film, and set the tone for the rest of the film score. The American Film Institute has included the song among its 100 best film songs, ranked at No. 53.

The release of Bassey’s “Goldfinger” single in 1965 sold more than a million copies in the U. S. alone. The song rose to No. 8 on the U.S. Billboard charts, remaining on that chart for 13 weeks. It also became an international hit, reaching No. 1 in Japan and rising into the Top Ten in many European countries. In 2008, the single was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame

The “Goldfinger” song was composed by John Barry, with lyrics by Anthony Newley and Leslie Bricusse. The film score was also composed by John Barry, and the resulting soundtrack album made heavy use of the brassy sound set out in Shirley Bassey’s opening song.

Music Player

“Goldfinger”-1964-1965

The Goldfinger soundtrack album went to No. 1 on the U.S. Billboard albums chart, spending 70 weeks there. It also rose to No. 14 on the U.K. albums chart, although the U.K. version had four tracks that didn’t appear on the American version. John Barry’s Goldfinger was also nominated for a motion picture film score Grammy.

“John Barry’s score ushered in a new style of swinging action music..,” observed Justin Craig of Fox News in one 2012 retrospective review of the film and its music. “Barry breathed an entirely new sound and style into movies and truly gave the entire Bond franchise its soul and musical identity. There’s no denying the impact Barry’s opening title song, performed by Shirley Bassey, has had on the future, of not only the Bond franchise, but music for the movies overall.”

Goldfinger was the first Bond film to use a pop star to sing a Bond movie theme song, and the practice would continue in subsequent Bond films.

Shirley Bassey would go on to sing two other Bond film theme songs — “Diamonds Are Forever” and “Moonraker.” Bassey already had a number of hits as a U.K. performer when she sang “Goldfinger,” but the Bond theme became her first true international hit.

In fact, the “Goldfinger” theme and “Diamonds Are Forever” became so famous for Bassey that she had difficulty establishing a pop career beyond those tunes. In February 2013, at the 85th Academy Awards ceremony in Hollywood, Bassey sang the famous “Goldfinger” theme song to to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the James Bond movie franchise. She received a standing ovation for her performance. Anthony Newley’s version of the “Goldfinger” song was included in a 30th anniversary compilation album, The Best of Bond…James Bond.

The Bond Legacies

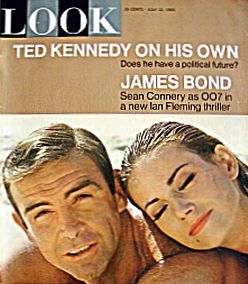

By July 1965, Sean Connery, with French co-star Claudine Auger, appeared on the cover of Look magazine at the filming of the next Bond film, “Thunderball.” Click for magazine.

Roger Ebert also wrote that James Bond was perhaps the most durable of the 20th century’s movie heroes, and the one likely to last into the 21st century. “He is a hero,” Ebert said of Bond, “but not a bore. Even faced with certain death, he can cheer himself by focusing instead on the possibility that first he might get lucky. He’s obsessed with creature comforts, a trial to his superiors, a sophisticate in all material things and able to parachute into enemy territory and be wearing a tuxedo five minutes later. When it comes to movie spies, Agent 007 is full-service, one-stop shopping.”

Added to Ebert’s perspective on Bond is the following description offered by The Museum of Modern Art of New York for its October 2012 exhibition, “50 Years of James Bond”:

Created by novelist Ian Fleming in 1953, the iconic James Bond, 007, is among the few MI-6 agents with the “00” grade—a license to kill. In addition to his deadly skills, the sophisticated, suave, and impeccably dressed Bond remains a loner, despite countless romantic encounters with stunning female spies, voluptuous assassins, provocative party-girls, and a charismatic psychopath or two. The alluring aura of danger and self-confidence he exudes is irresistible to women, but none are allowed to get too close.

Whether portrayed by Sean Connery, George Lazenby, Roger Moore, Timothy Dalton, Pierce Brosnan, or Daniel Craig, Bond is forever loyal to Queen and country, possessed of a martini-dry sense of humor, considerably stylish, and eternally enigmatic. When his boss, M, is in need of a formidable agent to quell a globe-spanning espionage crisis, 007 is sent into the field with his trusty Walther PPK [pistol], an array of handy spy gadgets, and an unwavering commitment to his mission.

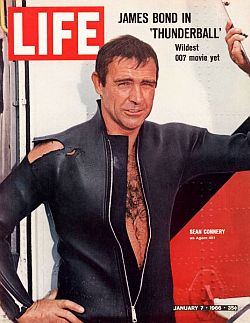

Life magazine, in January 1966, put Sean Connery on its cover as “Thunderball” was playing in theaters. He had been photographed earlier at the film’s shooting in the Bahamas.

As for the James Bond literary legacy, 007 publications have continued beyond Ian Fleming’s founding contributions, whose Bond books alone have sold more 100 million copies worldwide to date. Eight other writers – John Gardner and Raymond Benson among them – have contributed at least 20 more Bond novels since Fleming’s death, and there are more on the way. In May 2011, American writer Jeffery Deaver, released Carte Blanche, a book commissioned by Ian Fleming Publications that puts Bond in a post-9/11 world working independent of either MI-5 or MI-6. In 2012, the Fleming estate announced that William Boyd would write the next Bond novel, to be published by Jonathan Cape in London and expected for release in the fall of 2013. James Bond, it appears, will be with us for many years to come.

Other spy novel history at this website, and related film production, can be found in the story, “The Bourne Profitability.” For another James Bond story and its film music see: “You Only Live Twice: Film & Music, 1967.” Additional story choices in the film and/or publishing categories can be found at “Print & Publishing” or “Film & Hollywood,” or at the Home Page.

Thanks for visiting — and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research and writing at this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

____________________________________

Date Posted: 23 February 2013

Last Update: 31 October 2020

Comments to: jdoyle@pophistorydig.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Goldfinger, 1959-1965,”

PopHistoryDig.com, February 23, 2013.

____________________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

Sean Connery with James Bond creator, Ian Fleming. |

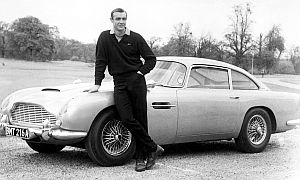

Sean Connery with famous James Bond sports car, the Austin Martin DB-5, complete with ejector seat! |

James Bond receiving a briefing from “Q” on the finer points of the DB-5, including its various armaments. |

“Books: The Upper-Crust Low Life” (Dr. No book review), Time, Monday, May 5, 1958.

Hugh Sidey, “The President’s Voracious Reading Habits; He Eats Up News, Books at 1,200 Words A Minute,” Life, March 17, 1961, pp. 55-60.

“Books: Of Human Bondage”( The Spy Who Loved Me book review), Time, Friday, April, 13, 1962.

“Can Bond Save Fort Knox From Goldfinger? – Agent 007 Takes on A Solid-Gold Cad,” Life, November 6, 1964, pp. 116-120.

“Cinema: Knocking Off Fort Knox,” Time, Friday, December 18, 1964.

Bosley Crowther, “Screen: Agent 007 Meets ‘Goldfinger’; James Bond’s Exploits on Film Again,” New York Times, December 22, 1964.

“Theater Open 24 Hours For ‘Goldfinger’ Showings,” New York Times, December 23, 1964.

“James Bond Film Series,” Wikipedia.org.

“Goldfinger (film),” Wikipedia.org.

“Book Covers, Ian Fleming Bond books, etc.,” Illustrated.007.

Roger Ebert, Film Review, “Goldfinger,” Sun Times.com, January 31, 1999.

Sam Howe Verhovek, “Newest Caper: James Bond in the Temple of Culture,” New York Times, June 8, 1987.

“Premiere Bond: Opening Nights,” IMDB .com, 2006.

Dave Kinney, “James Bond Aston Martin DB5 Sells for $4.6 Million,” New York Times, October 28, 2010.

Justin Craig, “Bond Turns 50: ‘Goldfinger’ Still Stands Out as Best of the 007 Bunch,” FoxNews.com, September 12, 2012.

Andy Greene, “The Top 10 James Bond Theme Songs,”Rolling Stone, October 5, 2012.

“Auric Goldfinger,” Wikipedia.org.

Alex Davies, “How Aston Martin DB5 Became The Ultimate 007 Ride,” BusinessInsider .com, October 23, 2012.

“Goldfinger (soundtrack),” Wikipedia.org.

Exhibitions, “50 Years of James Bond: October 5–31, 2012,” Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY (organized by Anne Morra, Associate Curator, Department of Film).

“James Bond (literary character),” Wikipedia .org.

“List of James Bond Novels and Short Stories,” Wikipedia.org.

“James Bond,” Wikipedia.org.

“Film Franchises: Pottering On, and On,” The Economist (London), July 11, 2011.

“Goldfinger,”Filmsite.org.

______________________