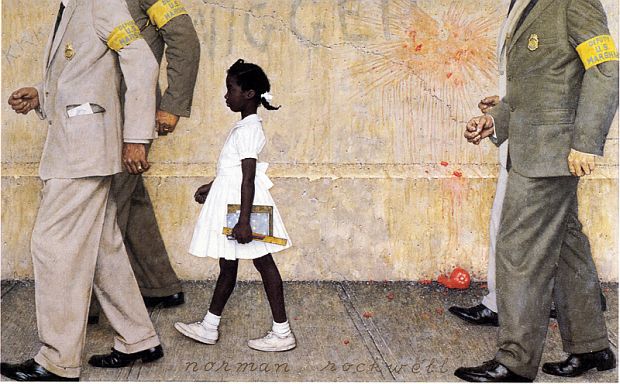

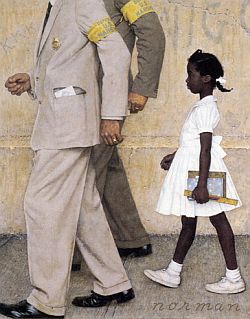

In June 2011 at the White House, Norman Rockwell’s 1963 painting, The Problem We All Live With, depicting a famous school desegregation scene in New Orleans, began a period of prominent public display with the support of President Obama. The White House exhibition of Rockwell’s piece, which ran most of 2011, drew national attention to an iconic moment in America’s troubled civil rights history.

Norman Rockwell’s famous painting of six year-old Ruby Bridges being escorted into a New Orleans school in 1960, was printed inside the January 14, 1964 edition of Look magazine, and also displayed at the White House in 2011. Click for wall print.

Rockwell’s painting focuses on an historic 1960 school integration episode when six year-old Ruby Bridges had to be escorted by federal marshals past jeering mobs to insure her safe enrollment at the William Frantz Elementary School in New Orleans. Ruby was the first African American child to enroll at the school, and the local white community – as elsewhere in the country at that time – was fiercely opposed to the court-ordered desegregation of public schools then occurring. Rockwell’s rendering focuses on the little girl in her immaculate white dress, carrying her ruler and copy book, as the four U.S. marshals escort her. The painting also captures some of the contempt of those times with the scrawled racial epithet on the wall and the red splattering of a recently thrown tomato.

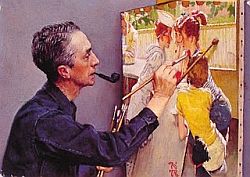

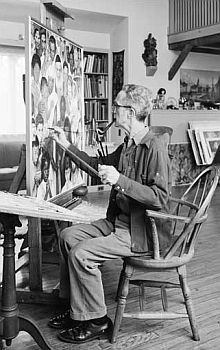

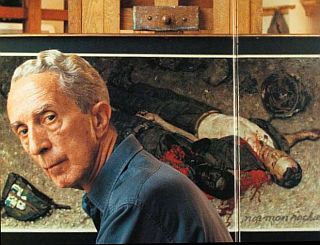

Norman Rockwell at work, mid-career.

The context of the Ruby Bridges scene rendered by Rockwell had been heavily reported in print and on television in November 1960, with the anger of the mobs that day burnished deeply in the public mind.

Magazine readers viewing Rockwell’s piece in 1964 would likely recall the unhappy context of young school children being heckled and needing federal protection.

July 15, 2011: President Obama with Ruby Bridges (girl in painting), Rockwell Museum CEO, Laurie Moffatt, and behind Obama, Rockwell Museum President, Anne Morgan, viewing Rockwell’s painting at the White House near the Oval Office. White House photo, Peter Souza.

“The President likes pictures that tell a story and this painting fits that bill…,” explained a statement in the White House blog. “In 1963 Rockwell confronted the issue of prejudice head-on…”

However, at the time of the painting’s White House display, some reporting had erroneously stated the Rockwell piece had initially appeared on the cover of the January 14th, 1964 Look magazine. That is a forgivable mistake given the fact that so much of Norman Rockwell’s work frequently did appear on magazine covers, most notably at the Saturday Evening Post. But the error raises an important question, nonetheless. Why didn’t the Rockwell painting of the famous civil rights incident run on the cover of Look magazine or some other magazine?

Norman Rockwell, circa 1940s.

Norman Rockwell

Born in 1894, Norman Rockwell grew up in New York city, and as a boy dreamed of becoming an artist. By the time he was ten he was drawing constantly. He soon dropped out of high school and enrolled in art school, first at the National Academy School, but by 1910, at the prestigious Art Students League. After graduation he did some of his first work for Boy’s Life magazine. In 1916, Rockwell did his first cover for Saturday Evening Post, then one of America’s premiere weekly magazines. For nearly the next fifty years, he would continue making much-loved Saturday Evening Post covers, most depicting everyday scenes of 20th century Americana. Rockwell in fact, would do more than 320 covers for the Saturday Evening Post through 1963. But that’s only part of his story.

1949: Game Called, Rain. |

|

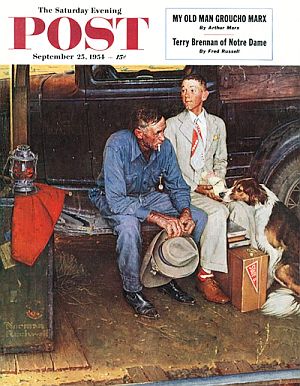

1958: The Runaway. |

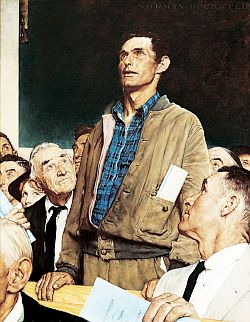

Rockwell’s cover subjects for the Post ranged across American daily life – from a young boy in a doctor’s office awaiting a curative needle or teenage girls gossiping at a soda fountain, to a rookie baseball player reporting to play his first game or a worn-out politician at the end of a hard day of campaigning. Some of Rockwell’s covers dealt with aspirational themes and democratic values. In 1942, in response to a speech given by President Franklin Roosevelt, Rockwell made his famous “Four Freedoms” series, each of which also ran as a Saturday Evening Post cover – Freedom of Speech (Feb 20, 1943), Freedom of Worship (Feb 27, 1943), Freedom from Want (March 6, 1943), and Freedom from Fear (March 13, 1943).

During this period as well, his Rosie the Riveter cover for the May 29th, 1943 edition of The Saturday Evening Post, and another depicting a “liberty girl” for the September 4th, 1943 edition, helped the government recruit female workers for the war effort during WWII. Some of these paintings traveled around the country in the mid-1940s, shown in conjunction with the sale of government war bonds. “The Four Freedoms” series reportedly brought in a tidy sum of $132,992,539 in war bond funds. Rockwell also did poster art for the U.S. Office of War Information in conjunction with the war bond drives.

Norman Rockwell at work on a 1953 painting for Saturday Evening Post cover, “Soda Jerk.”

Civil Rights Subjects

“Freedom of Speech” was one of a Rockwell’s “Four Freedoms” series admired by African American activist Roderick Stephens, who urged Rockwell in 1943 to do a similar series to promote racial tolerance. Click for wall print.

Stephens had been moved by Rockwell’s “Four Freedoms” and was worried at the time that urban race riots would ensue in major cities like his own New York, touched off by the migration of southern blacks to major cities. Race riots, in fact, had then already occurred in Houston, Los Angeles, and Detroit.

Although Stephens expressed his admiration to Rockwell for his “Four Freedoms,” he noted that two of the freedoms – “Freedom From Want” and “Freedom From Fear” – were, for most blacks at the time, freedoms denied. Stephens proposed that Rockwell do a series of paintings to be printed and circulated as posters, just as the “Four Freedoms” had been, to promote racial tolerance, featuring subject matter that would illustrate the contributions of blacks to American society and how they helped realize the Four Freedoms.

Stephens believed Rockwell was an artist who could make a difference at the time, and could help “advance racial goodwill by years,” offering art to point up what was then in American practice, a restricted conception of freedom. Rockwell is believed to have replied to Stephens, but he never embarked on Stephens’ proposal, more or less rejecting the series idea, explaining to Stephens the difficulties he had encountered creating the “Four Freedoms” series. But there may have been more to it than that, as Rockwell was then laboring under restrictions imposed by The Saturday Evening Post.

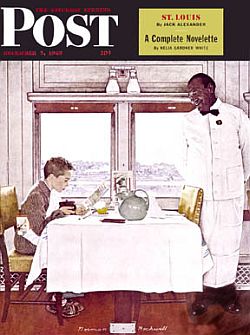

Dec 7 1946: “NY Central Diner,” Saturday Evening Post cover by Norman Rockwell.

In a 1971 interview with writer Richard Reeves, Rockwell explained the unwritten rule laid down by his first editor at the Post: “George Horace Lorimer, who was a very liberal man, told me never to show colored people except as servants.” Lorimer was Rockwell’s editor at the Post for his first twenty years there.

The Rockwell cover illustration at left from the December 7th, 1946 Saturday Evening Post illustrates the rule in practice. The scene, which is also known as Boy in Dining Car, shows a young boy in a railroad dining car studying the menu with purse in hand, trying to determine the proper payment and tip for the black waiter.

Rockwell’s “Full Treatment” SEP cover of May 1940 includes black shoe shine boy.

The Banjo Player, an illustration for a Pratt & Lambert varnish advertisement appearing inside The Saturday Evening Post of April 3rd, 1926;

Thataway, a March 17th, 1934 cover illustration for The Saturday Evening Post depicting a young black boy pointing to the direction taken by a thrown rider’s horse;

Love Ouanga, a June 1936 illustration for a short story in American Magazine depicting a beautiful, stylishly-dressed young African American woman in a church scene contrasted against more coarse and country dress of other farming and working African Americans also in the scene;

Full Treatment, a May 18th, 1940 cover for The Saturday Evening Post (at right) depicting a wealthy man being attended to by a barber, manicurist, and a black shoe shine boy;

The Homecoming, a May 26th, 1945 cover for The Post depicting a returning military veteran arriving home to a scene of welcoming family and neighbors that also includes an African American worker; and

Roadblock, a July 9th, 1949 cover for The Saturday Evening Post depicting a moving van that is blocked by a small dog in an urban alley scene with a variety on onlookers, including some black children.

Continuing into the 1950s and early 1960s, publishing art and mainstream magazines generally were slow to portray African American success stories and the civil rights struggle.

Cover Art, 1950s

1954: Segregation story. |

During the 1950s and early 1960s, a time when the civil rights movement was struggling for recognition, the American art community – then involved with modern art and abstract expressionism – was generally not doing battle with racial discrimination. Nor, for the most part, were America’s most popular magazines in that era featuring African Americans on their covers or doing prominent stories on civil rights.

In its May 8th, 1950 edition, Life magazine featured a photograph of baseball player Jackie Robinson on its cover, the first individual African American to be so featured by that magazine. Robinson had become the first African American to break the color barrier in professional baseball three years earlier with the Brooklyn Dodgers. Time magazine, for its part, had used an artist’s rendering of Robinson on an earlier cover in September 1947.

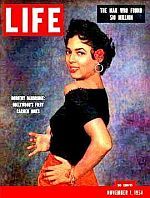

Back at Life, meanwhile, actress Dorothy Dandridge became the first African American woman to be featured on a cover at that magazine, for the November 1st, 1954 edition. Dandridge was then appearing in her Academy Award-nominated best actress film role in Carmen Jones.

A few stories on segregation also appeared on major magazine covers in the mid-1950s. On September 13, 1954, Newsweek ran a cover story on segregation in schools, showing a white and a black child in a Washington, D.C. school. Time magazine put Thurgood Marshall on the cover of its September 19th, 1955 issue, Marshall then having risen to notice as chief counsel for the NAACP arguing the landmark Brown vs. Board of Education school desegregation case before the U.S. Supreme Court. (see “Brown vs Board…” sidebar, later below, for more details).

A portion of the January 24, 1956 cover of Look magazine showing “Approved Killing” story tagline.

There was no mention of race in the story tagline, and it ran on a somewhat incongruous cover featuring the U.S. teenager (shown at left). But the “shocking story” inside the magazine was truly shocking. It featured the August 1955 murder of Emmett Till, a 14 year-old Chicago boy who was savagely beaten, shot, and mutilated by white men in Mississippi while the boy was visiting relatives there. Till, a brash kid who knew nothing about the mean realities of the segregated South, made the mistake of whistling at a white woman at a country store. Later abducted from his relatives’ home, Till was brutally pistol-whipped and dumped into a river, his body tied to a heavy metal fan.

Two white suspects – Roy Bryant and J. W. Milam – were tried in September 1955 and acquitted by an all-white jury in less than two hours. Their defense attorney had called on the jurors to honor their forefathers by not convicting white men for killing a black person. Back in Chicago, at the insistence of his mother, Till’s mutilated body was displayed at an open-casket viewing. And photos of Till’s disfigured and bloated face were published in the September 1955 edition of Jet magazine and also in The Chicago Defender, both African American publications. No mainstream print publication in America at that time published the gruesome photos. And in fact, the Look story referred to above and at right, and much of the subsequent mainstream media treatment of the Till murder, came after the Jet photos were circulated and seen. Time magazine later selected one of the Till photos as among the 100 “most influential images of all time” (see also video at this link).At Look magazine, meanwhile, the January 24th, 1956 story by William Bradford Huie covered the Till murder and also interviewed the two suspects, Roy Bryant and J. W. Milam, who were paid $4,000 to tell their story. In fact, in the article, the two suspects – then safe from conviction after having been acquitted in their friendly Mississippi trial – actually confessed to the Till murder. A year later, in its January 22nd, 1957 edition, Look published a follow-up article, “What’s Happened to the Emmett Till Killers?” That story reported that blacks in the local community stopped using stores owned by the Milam and Bryant families, putting them out of business, as both men were also ostracized by the white community. Both later died of cancer; Milam in 1980, Bryant in 1994. In March 2018, the U.S. Department of Justice stated that it was reopening the investigation into Till’s death due to unspecified new information.

Cover Art ( cont’d)

In many ways, the outrage over the Emmett Till murder, and the injustice that followed, helped energize the civil rights movement in the late 1950s and early 1960s. And at that time as well, some popular magazine coverage – and cover art subjects – began reflecting that change.

On September 3rd, 1956, Life magazine featured a cover story related to slavery and segregation – “Beginning A Major Life series – Segregation,” stated Life at the top of the cover. In the September 24th, 1956 edition of Life, inside the magazine, a 12-page spread of photos and story focusing on a black family and racial discrimination in the south were featured. That story was titled, “The Restraints: Open and Hidden.” The photos were those of Gordon Parks, who would become famous for his work as the first African American photographer at Life and other accomplishments. Parks would also do a later special photo essay and cover story for Life in March 1968 on race and poverty titled, “The Cycle of Despair: The Negro and the City.”

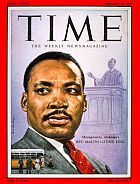

In 1957, Time magazine featured Martin Luther King on its cover February 18th, 1957, as King was then in the news for his leadership in the Montgomery, Alabama bus boycott. Later that year, on October 7th, 1957, Time and Life both featured the school integration conflict at Little Rock, Arkansas with National Guard troops shown on their covers. By the time of the Freedom Riders in 1961, a Newsweek cover story featured photos and quotes from three key players in the controversy: U.S. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, Martin Luther King, and Mississippi Governor, John Patterson.

In May 1963, Time’s cover featured author and activist James Baldwin, whose novel, The Fire Next Time, was then popular, portions of which had also been published in The New Yorker magazine. Newsweek’s cover of June 1963, featured Vivian Malone on the cover with a quote from President John F. Kennedy: “We owe them – and we owe ourselves – a better country….” Malone was one of the first two black students to enroll at the all-white University of Alabama in 1963, made famous when George Wallace, the Governor of Alabama, attempted to block her and James Hood from enrolling.

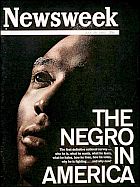

For its June 28th, 1963 edition, Life featured a cover photograph of the wife and child of slain civil rights activist Medgar Evers at his Arlington National Cemetery funeral. Evers, a Mississippi organizer, was shot in the back in his own driveway by a Ku Klux Klan member. In July 1963, Newsweek published a special issue on “The Negro in America,” picturing an unnamed black man on the cover. In smaller type on the cover, Newsweek further explained the focus of its series with the following: “The first definitive national survey – who he is, what he wants, what he fears, what he hates, how he lives, how he votes, why he is fighting … and why now?”

For its September 6th, 1963 issue, Life magazine featured a cover story on the historic August 1963 “march on Washington” with a photograph of two of its leaders, A. Phillip Randolph and Bayard Rustin, shown standing in front of the Lincoln Memorial. In March 1965, Life also ran a cover feature on the civil rights march at Selma, Alabama; the march that resulted in the “Bloody Sunday” clash. And as the civil rights movement received more national notice throughout the 1960s, more mainstream magazine coverage and cover features followed.

Rockwell & The Post

Norman Rockwell, meanwhile, was experiencing change at The Saturday Evening Post. By the early 1960s, the frequency of his covers there had slowed – down to a half dozen or so a year – and the magazine was experimenting with new formats. Still, after more than 40 years of his cover art being featured for millions of Post readers, Rockwell was clearly an asset to the magazine.

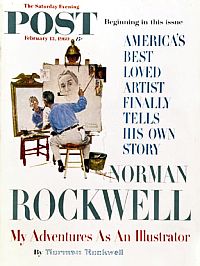

In fact, for the February 13th, 1960 issue of the magazine and its cover story, he was the featured star and title subject. The cover used his famous “triple self-portrait” and gave full billing to a beginning series of articles about him for the magazine taken from a new autobiography written with the help of his middle son, Thomas Rockwell.

Shown at right, the cover taglines for that issue of the Post explained: “Beginning in this issue: America’s Best Loved Artist Finally Tells His Own Story… My Adventures As An Illustrator.” Yet Rockwell was chafing at the Post by this time, and his days there were numbered.

1962: Art Connoisseur. |

1963: Nehru of India. |

Through the early 1960s, Rockwell continued doing Post covers. In 1960, for example he did five more Post covers in addition to “triple self portrait,” shown above, three of which offered traditional subjects: “Repairing Stained Glass,” April 16, 1960; “University Club,” August 27, 1960; and “Window Washer,” September 17, 1960 (with the washer ogling the secretary). Two more Rockwell covers that year were portraits of the 1960 presidential candidates – U.S. Senator John F. Kennedy and Vice President Richard M. Nixon.

The magazine by then had begun shifting to more portraits of famous people as cover material, and was also using more cover photography rather than illustrations or paintings. Rockwell cover portraits, in any case, held their own at the Post, and included others in the early 1960s, among them: Indian prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, January 19, 1963; Jack Benny, entertainer, March 2, 1963; a serious portrait of President John F. Kennedy to accompany a cover story on his foreign policy challenges, April 6, 1963; and Egypt’s Gamal Abdel Nasser, May 25, 1963.

Other more traditional Post covers by Rockwell in the early 1960s included: “Artist at Work,” Sept 16, 1961; “Cheerleader,” Nov 25, 1961; and “Art Connoisseur” of January 13 1962, showing a middle-aged man in a museum observing a Jackson Pollack-type painting (this issue also had cover billing for a story inside the magazine entitled, “The Little Known World of Our Negro Aristocracy.”).

One interesting departure for Rockwell from his normal Saturday Evening Post fare during the early 1960s – and a sign of his more liberal inner concerns – came with the April 1st, 1961 cover that appeared under the title “The Golden Rule.” This illustration actually had its genesis, in part, during the late 1940s when Rockwell had set out to do a painting honoring the United Nations (UN), an organization he admired and found hopeful for solving world problems. For the UN painting, Rockwell had in mind something that would highlight the cultural, racial, and religious tolerance of the organization, and he had visited the UN Security Council Chamber for ideas and sketches. His first efforts yielded a charcoal drawing of several major-nation delegates debating from their seats in a brightly lit foreground. Behind the delegates, in the shadows, was a crowd of more than sixty people – a cross-section of men, women, and children from around the world, some in native dress. But Rockwell had difficulty with the UN delegates agreeing to sit for the drawings, and he also had his own dissatisfactions with his art, so he set the project aside. Some years later, in 1960, he resurrected the project, then changing its composition somewhat and using “the golden rule” as theme. He also incorporated the phrase “Do Unto Others As You Would Have Them Do Unto You” directly into the painting using gold lettering.

Rockwell at work on “Golden Rule,” 1960.

Art critics have noted that these African American depictions were positive portrayals that broke with the traditional servile stereotypes at the Saturday Evening Post. And along with the other Asians and Africans shown, were Rockwell’s way of following his conscience and “integrating” a Saturday Evening Post cover on his own.

Rockwell also incorporated a portrayal of his second wife, Mary, in the painting. Mary was the mother of their three sons and had passed away in 1959. She is shown in the right middle of the painting holding their grandson she never saw. Rockwell is believed to have completed this painting in November 1960. He was later presented with the Interfaith Award from the National Conference of Christians and Jews for the painting, a citation he treasured.

By late 1963, Rockwell was about to embark on a career change. He was in his 60s by this time. The cover art at the Saturday Evening Post pretty much continued to focus on Americana and everyday life as it had in the past. Inside the magazine, however, there were contemporary stories of the day; the magazine was slowly changing.Still, Rockwell had become frustrated by the limits the Post had imposed upon his art, especially regarding political themes and social concerns. By then he had begun thinking about and moving on to other subject matter. So in December 1963, he ended his near half-century with the Saturday Evening Post.

Rockwell’s final cover for the magazine appeared in mid-December 1963. It was actually an earlier portrait of John F. Kennedy he had done during the 1960 presidential campaign which the Post republished in a special memoriam issue that ran after Kennedy’s assassination.

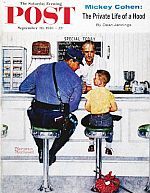

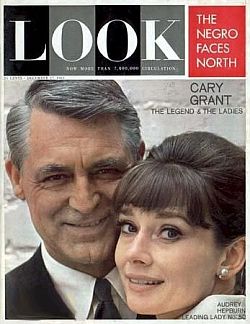

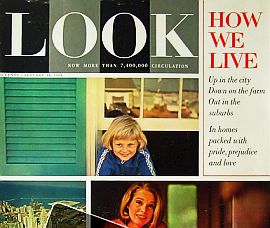

Look magazine at the time Rockwell signed on, Dec 1963, then featuring Hollywood’s Cary Grant & Audrey Hepburn, and 'The Negro Faces North'.

In December 1963, at the age of 68, Norman Rockwell signed on with Look magazine. Look covers at the time dealt with contemporary subjects, celebrities, and general topics of the day, using mostly photographs. A sample cover from December 1963 appears at left, this one also mentioning a civil rights story inside that edition.

Major circulation magazines in the early 1960s were beginning to feel the competition of television. Collier’s had ceased publication in 1956, and even the Saturday Evening Post was feeling the heat. Yet, Life and Look – the “picture magazines,” as they were sometimes called – remained strong, with solid advertising revenue. Look by the mid-1960s would have some of its best years for sales and circulation.

When Rockwell began doing work for Look, Dan Mich was editor there. Mich was a supporter of thought-provoking journalism, and along with art director Allen Hurlburt, they gave Rockwell freedom to pursue his “bigger picture” interests, as he called them. Look wanted to use Rockwell’s art as a compliment to current reportage and that gave Rockwell opportunity to pursue subject matter that interested him.

Rockwell’s third wife, Mary L. “Molly” Punderson, a fervent liberal, was an influence on Rockwell’s work through the 1960s, as was his friend and psychiatrist Erik Erickson. And Rockwell himself, despite being tagged “conservative” by association with his Saturday Evening Post covers, had his own internal guideposts and values, as already noted above. Rockwell was clearly more liberal/progressive than many of his Saturday Evening Post followers might have realized. Some who knew him described him as a “strict constructionist,” especially so when it came to American values. No surprise then, if given a subject and a free hand where American ideals such as freedom and equality of opportunity were at stake, his brush would be on the right side of those concerns.

Ruby Bridges exiting the William Frantz school in New Orleans, November 1960, with U.S. marshals.

Prior to the first integration actions in New Orleans – and there were two schools involved and several black students; three at another school – politicians in Louisiana, including the state’s governor at the time, segregationist Jimmie Davis, had maneuvered to prevent and forestall the integration. In September 1960, the schools there opened initially as segregated. By November, however, the courts had set a deadline to begin school integration, but parents did not know which schools would be involved

|

“Brown vs. Board…”  Ruby Bridges being escorted into school, November 1960.  A federal marshal driving first grader Gail Etienne to McDonogh 19 school in New Orleans, November 14, 1960, one of four black children who entered two previously all-white schools in the city. Times-Picayune photo. |

Rockwell’s Ruby Bridges

Sidewalk protest in New Orleans over school integration, November 15th,1960.

Rockwell, no doubt knew about all of this and likely read news accounts of the protests. On November 15, 1960, The New York Times reported the greeting Ruby and her mother received as they arrived that day: “Some 150 white, mostly housewives and teenage youths, clustered along the sidewalks across from the William Franz School when pupils marched in at 8:40 am. One youth chanted ‘Two, Four, Six, Eight, we don’t want to integrate’…”

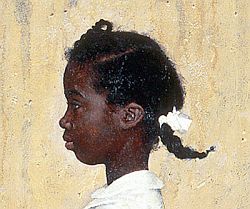

Detail from Rockwell painting showing young Ruby in escort and portions of scrawled epithets on wall.

The white parents kept up their boycott of the schools the entire year, and the protests and jeering continued periodically. On December 2nd, 1960, for example, housewives demonstrated at the William Frantz school, one standing with a placard that read “Integration is a Mortal Sin,” citing a biblical scribe as source.

Rockwell’s painting, of course, does not capture all of this, nor was it intended to. His focus appears to be solely on the girl, placed at center, giving no special notice to the marshals, other than they were needed, as he portrays them as anonymous and headless, from mid-torso down. The setting around the little girl is ugly and threatening, but she is innocent and perfect, as her white dress and ribbon-tied hair suggest. As far as she is concerned, she is just going to school.

One description of the 1960 New Orleans school integration protests that Rockwell may have read prior to or during his work on the Ruby Bridges painting was John Steinbeck’s observations of the episode, offered in his 1962 best-seller, Travels with Charley: In Search of America. “Charley” was Steinbeck’s dog and traveling companion during his road trip around the United States. Travels With Charley was published by Viking Press in the mid-summer of 1962, reaching No.1 on the New York Times nonfiction best- seller list October 21, 1962. In part four of that book, Steinbeck recorded his reactions on coming to the New Orleans communities where the school integration controversy had flared, and he came away gravely saddened by what he saw. In his book, Steinbeck offered a detailed account of Ruby Bridges’ arrival at the elementary school and her handling by the U.S. marshals:“…The show opened on time. Sound of sirens. Motorcycle cops. Then two big black cars filled with big men in blond felt hats pulled up in front of the school. The crowd seemed to hold its breath. Four big marshals got out of each car and from somewhere in the automobiles they extracted the littlest Negro girl you ever saw, dressed in starchy white, with new white shoes on feet so little they were almost round. Her face and little legs were very black against the white…The little girl did not look back at the howling crowd but from the size the whites of her eyes showed like those of a frightened fawn. The men turned her around like a doll, and then the strange procession moved up the broad walk toward the school, and the child was even more a mite because the men were so big…”

November 1960: Demonstrators during school integration in New Orleans, Louisiana; one holding sign that reads, “Integration is A Mortal Sin.”

“…No newspaper had printed the words these women shouted. It was indicated that they were indelicate, some even said obscene. . . . But now I heard the words, bestial and filthy and degenerate. In a long and unprotected life I have seen and heard the vomitings of demoniac humans before. Why then did these screams fill me with a shocked and sickened sorrow?…”

Steinbeck wrote that he knew “something was wrong and distorted and out of drawing” in what he had seen in New Orleans. He had formerly counted himself as a friend of New Orleans; knew the city fairly well, had his favorite haunts there, and also had many treasured friends there – “thoughtful, gentle people, with a tradition of kindness and courtesy.” Where were they now, he wondered – “the ones whose arms would ache to gather up a small, scared, black mite?” Answering his own question, he wrote:

“…I don’t know where they were. Perhaps they felt as helpless as I did, but they left New Orleans misrepresented to the world. The crowd, no doubt, rushed home to see themselves on television, and what they saw went out all over the world, unchallenged by the other things I know are there….”

Another influence on Rockwell at this time was likely Erik Erikson, a psychoanalyst at the Riggs Center in Stockbridge, Massachusetts where Rockwell then lived and worked. Erikson treated Rockwell occasionally for bouts of depression, was Rockwell’s friend, and also had a passion for civil rights. Erikson was a colleague and mentor to a younger child psychiatrist named Robert Coles, who had begun working with Ruby Bridges and other children in the early school desegregation cases in 1961. Coles had found that segregation had damaged the self-esteem of the little girls, and by 1963 he had written a series of articles beginning in March for The Atlantic Monthly magazine profiling Ruby Bridges’s experiences during integration of the Frantz school. He also published The Desegregation of Southern Schools: A Psychiatric Study, a short book. Erikson may well have made Rockwell aware of these at the time he was painting The Problem We All Live With.

Look magazine’s cover story of January 14, 1964 focused on “How We Live” – American’s homes and communities – city, farm & suburb. Rockwell's Ruby was inside.

On the Look cover there was no special mention or billing of Norman Rockwell’s painting. The illustration would be found in the middle of the magazine as a full two-page spread with no accompanying text. In the table of contents it was billed under “art” with the title “The Problem We All Live With.” It appeared amidst a series of articles with titles such as: “Their First Home,” “Down On The Farm,” and “Their Dream House Is On Wheels.” One of the stories focused on Theodore and Beverly Mason, a black family living in a mixed community in Ludlow, Ohio.

Detail from “The Problem We All Live With.”

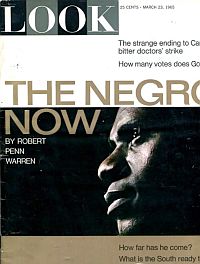

Apart from Rockwell’s work, Look also published cover stories on civil rights issues in that period. On March 23, 1965 the magazine featured “The Negro Now” story by Robert Penn Warren on its cover, describing its content with a series of questions, also on the cover: “How far has the Negro come?,” “What is the South ready to concede?,” “What happens next in the North?,” “Can we move forward without violence?,” and “Who speaks for the Negro now?”

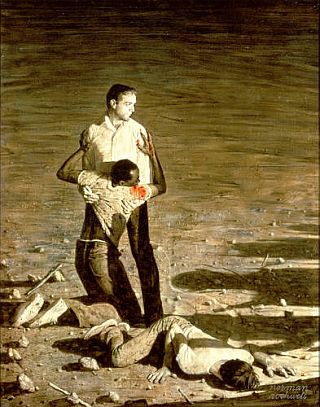

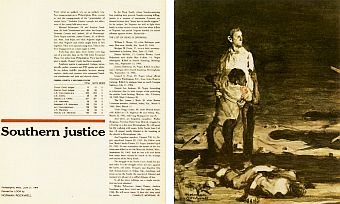

Rockwell’s “Southern Justice” painting of 1965, also known as “Murder in Mississippi,” depicting the killings of three civil rights workers murdered in June of 1964.

Another step that Norman Rockwell took with his civil rights painting in the 1960s, came when he ventured into depicting violence then occurring in the civil rights movement. In 1964, he began work on a painting inspired by the murder of three young civil rights workers in Mississippi in June of 1964.

The three young men – James Chaney, a 21 year-old black man from Meridian, Mississippi; Andrew Goodman, a 20 year-old white Jewish anthropology student from New York; and Michael Schwerner, a 24 year-old white Jewish organizer and former social worker also from New York – were helping to register black voters in Mississippi. Initially, the three men were reported missing.

Within days of their disappearance, the story made national headlines, as President Lyndon Johnson ordered a massive search. However, it turned out that shortly after midnight on June 21, 1964, the three civil rights workers were murdered by local members of the Ku Klux Klan, aided in their plot by a local police chief. All three were beaten and then shot, and their bodies not located until August 8, 1964, found buried beneath an earthen dam.

Michael Schwerner, James Chaney and Andrew Goodman – the three civil rights workers who were murdered in Mississippi, June 1964. FBI photos. Click for related book.

Norman Rockwell’s rough study sketch of beaten civil rights workers as it ran with article in Look magazine, June 29, 1965.

As with the Ruby Bridges episode, Rockwell no doubt learned of this civil rights story through the media accounts and newspaper reporting of that day. On June 22, 1964, for example, the New York Times ran a front-page story on the incident using the following headlines and description: “3 In Rights Drive Reported Missing; Mississippi Campaign Heads Fear Foul Play–Inquiry by F.B.I. Is Ordered….” After the three workers were found dead, however, local officials in Mississippi refused to prosecute the suspected killers. The U.S. Justice Department then charged eighteen individuals with conspiring to deprive the three workers of their civil rights (by murder). Seven were found guilty on October 20, 1967, but with appeals, did not begin serving their 3-to-10 year sentences until 1970, with none serving more than six years. Three other suspects had been acquitted, but no further legal action ensued in the case until pressure was brought decades later, in June 2005, when the state of Mississippi prosecuted and convicted Edgar Ray Killen – who planned and directed the killing – on three counts of murder.

Look magazine, meanwhile, went on to do other stories on civil rights issues. Less than a year later, on May 3, 1966, Look ran a cover story on the Ku Klux Klan showing a hooded Klansman on the cover wielding two flaming torches. Rockwell had done some other work for Look in 1965 following his Southern Justice illustration. For the July 27, 1965 edition of Look, Rockwell did an illustration to accompany an article on President Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty program for the poor, entitled “How Goes the War on Poverty.” Rockwell’s illustration featured a “helping hand” clasped to another’s seeking help, superimposed over a background of diverse faces with a quote from President Johnson lettered into the painting: “Hope for the Poor, Achievement for Yourself, Greatness for Your Nation.” In the following year, for the June 14, 1966 edition of Look, Rockwell did the cover art and four other pieces inside the magazine helping to illustrate a story on The Peace Corps – “J.F.K.’s Bold Legacy.” Rockwell’s cover piece included a profile of John F. Kennedy and others who actually served in the Peace Corps (some of whom also modeled for Rockwell as he did the painting), including one African American female. All were shown on the cover in profile looking left, with Kennedy in front (see cover above). Rockwell had thrown himself into the Peace Corps project, actually visiting Peace Corps volunteers in action in Ethiopia, India, and Colombia during 1966 as he created several narrative scenes of them at work. But Rockwell would also do more civil rights work the following year, also published in Look.

Look, Nay 1967: "Suburbia." |

Story: Negro in the Suburbs. |

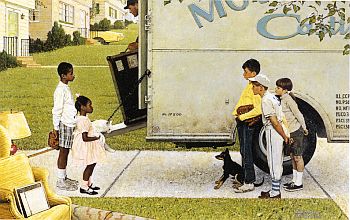

“New Kids…”

The May 16th, 1967 issue of Look magazine was billed as “A Report on Suburbia” – with added tagline, “The Good Life In Our Exploding Utopia.” Look’s cover for that edition also listed the line-up of suburban-related stories inside: “Parties and Prejudices,” “New Styles and Status,” Morals and Divorce, and “Teenagers in Trouble.” One of the stories to follow was by Jack Star, entitled “Negro in the Suburbs.” Mrs. Jacqueline Robbins, a young black housewife who then lived in the all-white Chicago suburb of Park Forest, Illinois with her chemist husband, Terry, 32, and their two sons, was quoted as saying, “Being a Negro in the middle of white people is like being alone in the middle of a crowd.” A Rockwell illustration — entitled New Kids in the Neighborhood — ran in the middle of that article. “Although Negroes are still a rarity in the green reaches of suburbia,” reported the Look article, “they are emerging from nearly all the large metropolitan ghettos with increasing frequency.” In Chicago during 1966, the story explained, 179 Negro families moved into white suburbs – more than twice as many as in the previous year, seven times as many as in 1963…”

Norman Rockwell’s “New Kids in the Neighborhood” ran as full two-page centerfold in Look magazine, May 16, 1967. Click for print.

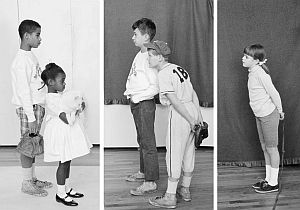

Child models used by Rockwell for “New Kids,” 1967.

“Blood Brothers”

A black and white copy of Norman Rockwell’s “Blood Brothers” painting which he later gave to CORE.

What Rockwell began to sketch were two dead men on the ground – one black and one white – both bloodied and beaten, found on a ghetto street after a riot lying parallel to one another, their blood co-mingling in a pool on the ground. According to the Norman Rockwell Museum, “Rockwell hoped to show the superficiality of racial differences – that the blood of all men was the same.”

Norman Rockwell, 1968, in front of easel with his “Blood Brothers” painting as shown in photograph from Ben Sonder book, “The Legacy of Norman Rockwell.”

Rockwell wasn’t happy with the decision, did some soul searching and talked with friends about the painting, but set it aside and moved on to other work. But later that year, Rockwell received an invitation from the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE), a civil rights group founded by students at the University of Chicago in 1942. CORE was active in desegregation protests and sits-in from its founding, and became a leading civil rights group in the 1960s, especially in the South, and also helped sponsor the 1963 March on Washington and other events. CORE wanted Rockwell to do an illustration for a Christmas card that the organization likely planned to use to send to its membership or perhaps for fundraising. But Rockwell did not send the group a typical Christmas or Holiday-themed illustration. Instead, he sent them the Blood Brothers painting. CORE, in any case, was happy to have Blood Brothers. However, it is not known how CORE used the painting or whether the group reproduced it for other purposes. One account has reported that the painting is missing from the CORE collection. The earlier studies and sketches Rockwell did for the painting are still held at the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge.

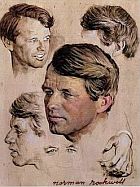

Rockwell RFK sketches.

Also in 1968, Rockwell’s Right to Know – a painting of a diverse group of citizens addressing their government – was published in Look’s August 20th edition. The 74 year-old artist had a number of other projects ongoing that year as well, including advertising work and illustrations for a children’s book. He also found time that year to appear on the Joey Bishop Show and the Tonight Show with Johnny Carson.

Belated Recognition

Norman Rockwell continued painting through his 70s. However, it was only in his latter years that his work began to be recognized for its artistic value. During much of his professional life, especially during his Saturday Evening Post years, Rockwell’s work was dismissed by many art critics who regarded his portrayals of American life to be idealistic or too sentimental. They did not consider him a “serious painter;” others believed his talents were wasted or put to frivolous purpose. Yet time would work in Rockwell’s favor.

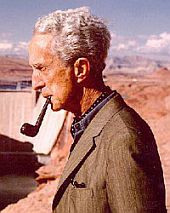

Norman Rockwell, later years.

In 1969, having lived in Stockbridge, Massachusetts for last quarter of his life, he agreed to lend some of his works to the Stockbridge Historical Society for a permanent exhibition. Word soon spread that his works were on display there and attendance grew annually, into the thousands. By 1973, then in his late 70s, Rockwell established a trust to preserve his collection, placed initially in a custodianship that would later became the Norman Rockwell Museum of Stockbridge. In 1977, Rockwell was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by then-President Gerald R. Ford, recognizing his “vivid and affectionate portraits of our country.” The following year, on November 8, 1978, Rockwell died at his Stockbridge home at the age of 84. An unfinished painting remained on his easel.

Rockwell’s “Rosie the Riveter” became a WWII & women’s rights icon. The original painting sold for $4.95 million in 2002. Click for Rosie's story.

Today, Norman Rockwell originals fetch millions at auction, and in recent years the values have been jumping. Rockwell’s Rosie the Riveter painting, used for a Saturday Evening Post cover in 1943 shown at right, was sold twice in recent years – once in 2000 for $2 million, and when resold again in May 2002, escalated to $4.95 million.

In May 2006, Rockwell’s Homecoming Marine sold for $9.2 million at auction. And in November 2006 at Sotheby’s in New York, his Breaking Home Ties sold for $15.4 million.

Collectors of Rockwell art today include the Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Smithsonian, The National Portrait Gallery, the Corcoran Gallery, George Lucas, Steven Spielberg, and others.

1994 U.S. postage stamp for Norman Rockwell’s “Freedom From Want.”

For additional stories at this website on magazine history, magazine cover art, and magazine advertising, see “Magazine History,” a topics page with links to 18 stories. For civil rights history, see “Civil Rights Topics,” a directory page listing 14 stories in that category. Thanks for visiting – and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research and writing at this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

____________________________________

Date Posted: September 23, 2011

Last Update: November 24, 2021

Comments to: jdoyle@pophistorydig.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Rockwell & Race, 1963-1968,”

PopHistoryDig.com, September 22, 2011.

____________________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

1940s: Norman Rockwell at work on a magazine cover. |

"Thataway" - March 1934 Saturday Evening Post cover; example of early "rule" on African American depiction. |

Nov 29, 1960: White parent, Rev. Lloyd Foreman (left) walks his five-year-old daughter Pam to the newly integrated William Frantz School where they were blocked by jeering crowd. At right is AP reporter Dave Zinman. AP photo. |

Nov 30, 1960: White parent Mrs. James Gabrielle, with police escort, is harassed by protestors as she walks her young daughter home after day in the newly integrated William Frantz school in New Orleans. Crowd wanted total white boycott. AP photo. |

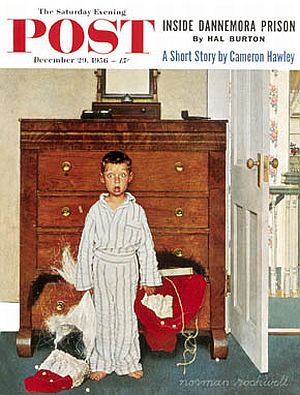

Norman Rockwell’s "Truth About Santa" or "Discovery,” captures the complete surprise of a crestfallen young boy who has discovered Dad’s Santa suit. SEP cover, December 29, 1956. |

DeNeen Brown, “Iconic Moment Finds a Space at White House,” Washington Post, Monday, August 29, 2011, p. C-1.

“Norman Rockwell,” Wikipedia.org.

Richard Reeves, “Norman Rockwell is Exactly Like a Norman Rockwell,” New York Times Magazine, Sunday, February 28, 1971, p. 42.

“Norman Rockwell Saturday Evening Post Covers in Order of Publication,” My-Mags.com.

Katy Reckdahl, “Fifty Years Later, Students Recall Integrating New Orleans Public Schools,” Times-Picayune,(New Orleans, LA), Saturday, November 13, 2010 (with photo gallery).

Angelo Lopez, “Norman Rockwell and the Civil Rights Paintings,” EveryDay Citizen.com, February 11, 2008.

Kirstie L. Kleopfer, “Norman Rockwell’s Civil Rights Paintings of the 1960s,” Master of Arts Thesis, University of Cincinnati, Department of Art History of the School of Art, College of Design, Architecture, Art & Planning, Cincinnati, Oho, May 16, 2007.

“Killers’ Confession: The Confession in Look,” PBS.org (Reprint of January 1956 Look article, “The Shocking Story of Approved Killing in Mississippi,”by William Bradford Huie).

“Freedom Summer: Newsweek Civil Rights Covers,” DailyBeast.com, 2011.

Richard Halpern, Norman Rockwell: The Underside of Innocence, University of Chicago Press, 2006, 201pp.

“Rockwell’s Four Freedoms: The Historical Context,” Fulbright American Studies Institute, University of Illinois at Chicago.

“Rockwell’s Four Freedoms: The Paintings Evolve,” Fulbright American Studies Institute, University of Illinois at Chicago.

“Four Freedoms (Norman Rockwell),” Wikipedia.org.

“Building Bridges,” Teachers College, Columbia University, June 1, 2004.

Ken Laird Studios, “The Problem We All Live With” – The Truth About Rockwell’s Painting,” HubPages.com, 2009.

Leoneda Inge, “Norman Rockwell And Civil Rights,” North Carolina Public Radio, WUNC, Friday, December 17, 2010.

Andy Brack, “Rockwell Painting Nudged Nation,” LikeTheDew.com, January 18, 2010

Robert Coles, “In the South These Children Prophesy,” Atlantic Monthly, March 1963.

Robert Coles, The Story of Ruby Bridges. New York: Scholastic Press, 1995 [ Tells the story of Ruby Bridges’ first year of school through words & illustrations; for children, ages 4-8 ].

Ruby Bridges, Through My Eyes, New York: Scholastic Press, 1999.

“Ruby Bridges,” Wikipedia.org.

“‘Brown v. Board at Fifty’- When School Integration Became the Law of the Land,” Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Claude Sitton, “3 In Rights Drive Reported Missing; Mississippi Campaign Heads Fear Foul Play–Inquiry by F.B.I. Is Ordered…,” New York Times, June 24, 1964, p. 1.

Joseph Lelyveld, “A Stranger In Philadelphia, Mississippi,” New York Times Magazine, December 27, 1964, p. 139.

William Bradford Huie, Three Lives for Mississippi, Jackson, MS: University of Mississippi Press, 2000 (first published in 1965).

Shaila Dewan, “Former Klansman Guilty of Manslaughter in 1964 Deaths,” New York Times, June 22, 2005.

“Look Magazine on ‘Suburbia’,” America on the Move, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Inst., Washington, D.C.

Louie Lamone (American, 1918–2007). Photographs for New Kids in the Neighborhood, Exhibitions: “Norman Rockwell: Behind the Camera,” Brooklyn Museum.

Laura Claridge, Norman Rockwell: A Life, New York: Random House, 2001.

Brian Lamb, Conversation with Laura Claridge, author, Norman Rockwell: A Life, Booknotes-TV (video), C-Span.org, October 11, 2001.

“Norman Rockwell, Cover Gallery, 1920s,” CurtisPublishing.com.

“Norman Rockwell, Cover Gallery, 1940s,” CurtisPublishing.com.

“Norman Rockwell Biography,1953 Through 1978,” Best-Norman-Rockwell-Art.com.

Thomas S. Buechner, Norman Rockwell, Artist and Illustrator, New York: Abrams, 1970. (includes reproductions of 600 Rockwell’s illustrations).

Norman Rockwell, My Adventures as an Illustrator: An Autobiography, Indian-apolis: Curtis Publishing, 1979.

Anistatia R. Miller, “Norman Rockwell,” Illustration, 1994 Hall of Fame, Art Directors Club, 1994.

Maureen Hart-Hennessey and Anne Knutson (eds), Norman Rockwell: Pictures for the American People, New York: Abrams, 1999.

G. Jurek Polanski, Review, “Norman Rockwell: Pictures for the American People” (at Chicago Historical Society, Feb 26 – May 21, 2000), ArtScope.net.

“The U.S. Civil Rights Movement,” Photo Gallery, State.gov.

Linda Szekely Pero, “Norman Rockwell, Year by Year – 1968,” Portfolio, Magazine of the Norman Rockwell Museum, Autum, 2004, pp. 8-14.

Carol Vogel, “$15.4 Million at Sotheby’s For a Rockwell Found Hidden Behind a Wall,” New York Times, November 30, 2006.

Jack Doyle, “Rosie The Riveter, 1941-1945” (WWII & women’s rights icon), PopHistory Dig.com, February 28, 2009.

Ted Kreiter, “Norman Rockwell: Getting the Real Picture,” SaturdayEvening Post.com, 2009.

Carol Kino, “The Rise of the House of Rockwell,” New York Times, February 4, 2009.

“The Art of Rockwell” (Gallery), New York Times.com, February 2009.

CBS News, “Lucas and Spielberg on Norman Rockwell,” CBS.com, July 10, 2010.

Brooklyn Museum, Teacher Resource Packet, Norman Rockwell: Behind the Camera, November 19, 2010–April 10, 2011.

“The Saturday Evening Post: Norman Rockwell Covers,” My-Mags.com.

“Life Covers: Civil Rights,” Photo Gallery, Life.com.

See Also, These Stories:

Jack Doyle, “Dylan: Only A Pawn…, 1963” (Bob Dylan’s Medgar Evans song & other civil rights music, w/video link), PopHistory Dig.com, November 23, 2010.

Jack Doyle, “Strange Fruit, 1939” (Billie Holiday song history & bio), PopHistory Dig.com, March 7, 2011.

Jack Doyle, “Motown’s Heat Wave, 1963-1966″(Motown music history), PopHistory Dig.com, November 7, 2009.

Jack Doyle, “Reese & Robbie, 1945-2005” (Brooklyn baseball statue of Jackie Robinson & Pee Wee Reese), PopHistory Dig.com, June 29, 2011.

Jack Doyle, “When Harry Met Petula, April 1968″(television, music & civil rights history), PopHistoryDig.com, February 7, 2009.

______________________________