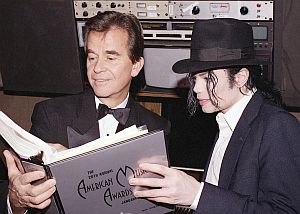

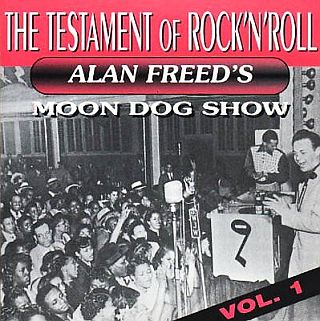

1950s dance-concert scene with Alan Freed (far right) as DJ & emcee. CD cover for collection of 1950s songs from Freed’s radio years. Famous Grove Records / 1997-98. Click for CD.

The normal fare of the day was mostly a mixture of Big Band music, old standards, Frank Sinatra-style crooners, a few pop tunes, and some novelty songs. Among the No. 1 singles in 1950, for example, were: “I Can Dream, Can’t I,” by The Andrews Sisters; “Chatta-nooga Shoe Shine Boy,” by Red Foley; “Music! Music! Music!,” by Teresa Brewer; “Mona Lisa” by Nat King Cole; and “The Tennessee Waltz,” by Patti Page, among others.

But this style of music – which would remain a standard genre for years – was making room for a new sound and a new kind of music. And one place where the new music was being broadcast on the radio was in Cleveland, Ohio by a late-night disc jockey named Alan Freed.

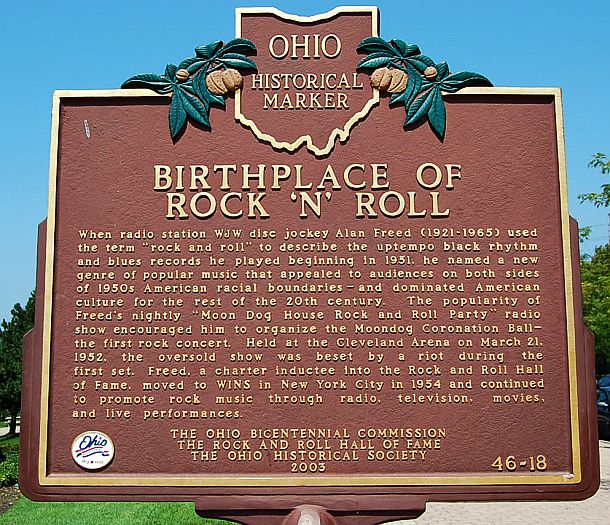

Working at station WJW and using the on-air nickname “Moondog,” Freed in 1951 was playing a mixture of rhythm and blues (R&B) music — music performed and listened to by mostly African Americans; music that was not widely played on mainstream radio. This was the music that would soon be known as “rock ’n roll” – a name that Freed would later be credited with advancing, if not inventing.

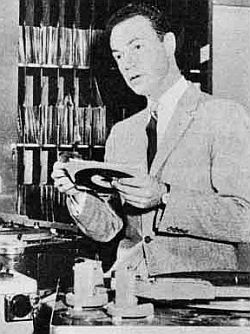

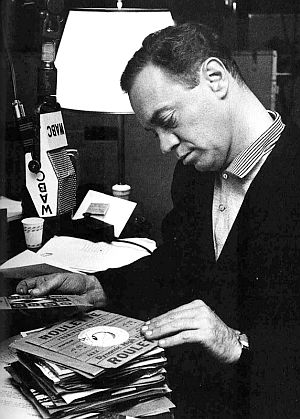

“Moondog” Alan Freed in 1951 at Cleveland radio station WJW where he called the new music he played, “rock ’n roll.”

R&B music was then also known as “race music;” music that was played largely in the black community but rarely in white America. R&B music was racially-segregated, like much of American society then. But Alan Freed at WJW in Cleveland soon began using the music as a centerpiece of his broadcasts. Freed began his program of R&B music in July 1951 and he would later start calling it “rock ’n roll” music. He would also fashion a new kind of “DJ talk” during his broadcasts, ad-libbing and using part of the language he heard on the recordings he was offering.

“Yeah, daddy,” he would say, “let’s rock and roll!” He was 29 years old at the time. His late-night show was called “The Moondog House” and it soon became popular with the young kids – black and white – of Cleveland, Ohio and beyond. In fact, Alan Freed would be credited as one of the early prime movers of “rock ’n roll” music and the early rock concert business. And Cleveland, the town where the rock `n roll broadcasts began, would later be honored with the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame museum as tribute to Freed. But when Freed came to Cleveland in the early 1950s, he had not come with the idea of broadcasting R& B music.

Alan Freed

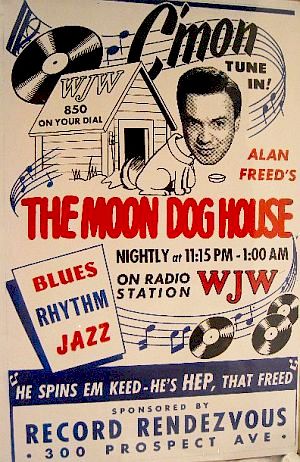

Early 1950s print ad for Alan Freed’s radio show on Cleveland’s WJW, sponsored by the Record Rendezvous.

By 1949 Freed had moved to WXEL-TV in Cleveland. There, Freed would later meet record store owner Leo Mintz in early 1951 who urged him to emcee a program of R&B music over WJW radio.

Mintz was the owner of the Record Rendezvous, one of Cleveland’s largest record stores, and he had noticed young white kids buying what had been considered exclusively black music a few years earlier.

Mintz believed that the R& B music was appealing to the white kids because of its beat, and that it could be danced to easily. He also proposed buying airtime on the station to help sponsor the R & B show. Record Rendevous would also appear in print ads promoting Freed’s shows, as illustrated in the ad above, which uses some radio lingo to pitch its ad slogans, such as: “He spins ‘em keed, he’s HEP, that Freed!”

Disc jockey Alan Freed shown in studio with 45 rpm recording in hand to play on his show.

Freed used an instrumental song, “Moondog Symphony,” as his show’s theme, a song by a New York street musician named Louis T. Hardin who also used the name “Moondog.” Others report that Freed used the song, “Blues for Moon Dog” as his radio theme, a song by Todd Rhodes.

On his show, Freed would later call the music he played, “rock `n roll,” a term found throughout R&B music. He wasn’t the first to use the term, but he became the first DJ to program R&B music for a much larger listening audience, helping to take the music business in a whole new direction.

WJW at the time was a 50,000-watt clear channel station powerful enough to reach a giant market throughout the Midwest. David Halberstam, describing Freed’s rise in his book The Fifties, wrote:

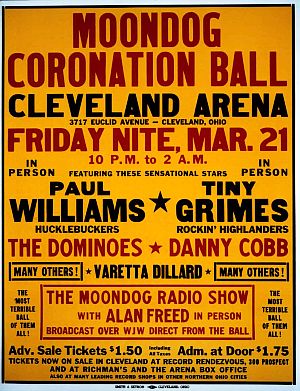

Poster advertising Alan Freed’s “Moondog Coronation Ball,” March 21st, 1952, Cleveland, Ohio.

“…His success was immediate. It was as if an entire generation of young white kids in that area had been waiting for someone to catch up with them. For Freed it was what he had been waiting for; he seemed to come alive as a new hip personality. He was the Moondog, He kept the beat himself in his live chamber, adding to it by hitting on a Cleveland phone book. He became one of them, the kids, on their side as opposed to that of their parents, the first grown-up who understood them and what they wanted. By his choice of music alone, the Moondog has instantly earned their trust. Soon he was doing live rock shows. The response was remarkable. No one in the local music business had ever seen anything like it before. Two or three thousand kids would buy tickets …all for performers that adults had never even heard of.”

Freed’s dance concerts were advertised over his radio show and he would also emcee the live shows, appearing as the DJ, introducing guest acts, and playing records at the site. In March 1952, he promoted a dance concert to be held at the Cleveland Arena that he called the “Moondog Coronation Ball,” which some claim as the first rock concert. A number of live R& B acts were also billed as part of this concert, including Paul Williams & The Hucklebuckers, Tiny Grims & The Rockin’ Highlanders, The Dominoes, Danny Cobb, and Varetta Dillard.

March 21st 1952: Scene at the Moondog Coronation Ball at the Cleveland Arena, just before things got out of hand. Photo, Peter Hastings/Cleveland Plain Dealer.

Over 20,000 young teens showed up for the 10,000-person ice hockey facility. A riot ensued as the crowd broke into the rink. The police responded and the concert was shut down. Part of the problem was due to the fact that a second night of Moondog Ball entertainment was planned to follow the first night, but all of the tickets for both nights were printed with the first night’s date, March 21st. In any case, the riot that resulted became the talk of the town, as the community was outraged. But the incident only raised the visibility of Freed and his radio show, then becoming more popular among teens.

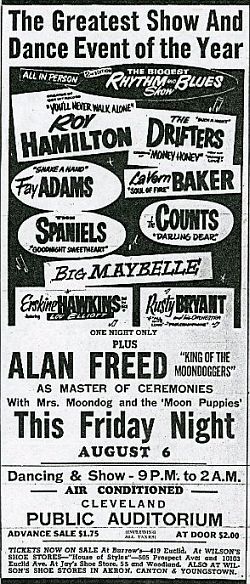

August 1954. Print ad for big R&B revue show in Cleveland with Alan Freed hosting.

“It is 1953, and Alan Freed is on the air again for his late night Moondog Show on WJW… Freed yips, moans and brays, gearing up for another evening hosting the hottest rhythm & blues show in the land. Slipping on a golf glove, he bangs on a phone book in time to the music – maybe ‘Money Honey’ by the Drifters, or ‘Shake a Hand’ by Faye Adams… [H]e spins the hits and continues his manic patter throughout the night, spewing forth rhymed jive with the speed and flections of a Holy Roller at the Pearly Gates.”

In 1953, when “The Biggest Rhythm and Blues Show” (run by the Gale Theatrical Agency) came to Cleveland on tour that summer, Freed was the featured emcee. On July 17,1953, thousands came out for that show at the Cleveland Arena, which also featured boxing star and celebrity Joe Louis for a brief appearance, as well as a full roster of performers including: Ruth Brown, Wynonie Harris, Leonard Reed, the tap dancing Edwards Sisters, Dusty Fletcher, Stuffy Bryant, and the Buddy Johnson Orchestra. That tour drew a largely black audience and became the largest grossing R&B revue of its day. In 1954, a similar tour again came to Cleveland in August, with Freed running that show as well.

These R&B revues, and Freed’s own stage shows and dances, drew tens of thousands of teens, black and white. Freed’s broadcasts from WJW in Cleveland, meanwhile, were being picked up by some radio stations in the East, on Newark, New Jersey station WNJR, for example, where the show found a receptive audience.Freed’s broadcasts were being picked up by radio stations in the East, and his on-air style was now spreading to other DJs who played a similar mix of music. Freed’s on air radio style was also spreading to other DJs, who played a similar mix of music. And by the early- and mid-1950s, the new rock ‘n roll music was also being listened to on small, hand-held transistorized radios, then selling for $25 to $50.

In May 1954, Freed traveled to Newark, New Jersey where he held the “Eastern Moondog Coronation Ball” at the Sussex Avenue Armory in Newark. It was Freed’s first personal appearance in the New York area. Among the R&B artists who appeared there were: Buddy Johnson and his orchestra and vocalist Ella Johnson; The Clovers, a vocal quartet; Roost Bonnemera and his Mambo Band; Nolan Lewis, Mercury recording star; Sam Butera, jazz saxophonist; Muddy Waters, blues guitar player; the Harptones; and Charles Brown. A crowd of some 11,000 came out for Freed’s Newark show. RCA Victor recorded the entire show for use on a special Moondog album. Our World magazine also covered the event in a featured pictorial story.

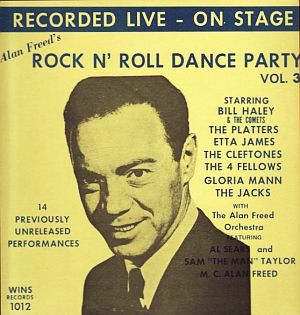

In September 1954, Alan Freed would move from WJW in Cleveland, Ohio to WINS in New York City.

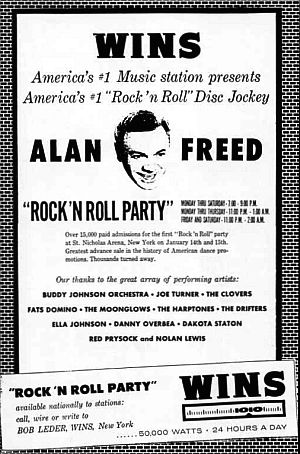

January 1955: “Billboard” magazine ad for Alan Freed’s shows on WINS radio, New York.

In September 1954 Freed was hired by WINS radio in New York. There he would receive a $75,000-a-year salary plus a percentage of syndication, as more than 40 radio stations would sign up to either simulcast or rebroadcast his show. Freed’s “Rock ’n Roll Party #1″ was broadcast Monday through Saturday in the 7:00-9:00 p.m. time slot. Another late night show, “Rock ’n Roll Party #2,” was broadcast Monday through Thursday in the 11:00 p.m.- 1:00 a.m. slot and Fridays and Saturdays, 11:00 p.m.-2:00 a.m.

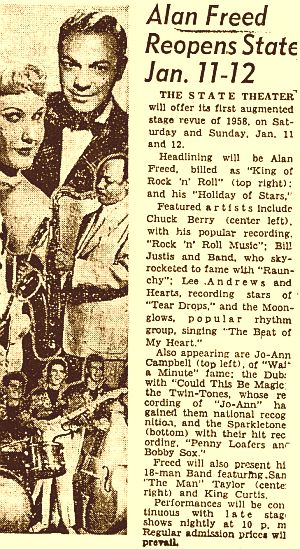

Freed’s live concert dance shows, meanwhile, soon became New York sensations. On January 14th and 15th, 1955 he held a landmark dance at the St Nicholas Ballroom in Manhattan, promoting black performers as rock ’n roll artists. Each night was a sellout, with some 12,000 jamming the hall. The gate for the two nights was $27,500, pretty good money in those days. Among the performers were Joe Turner and Fats Domino.

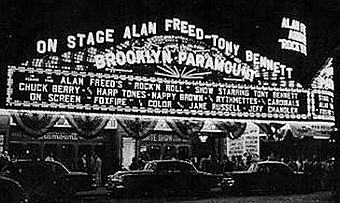

Freed also became known for his New York stage shows at the Brooklyn and New York Paramount Theaters. At one of Freed’s Brooklyn Paramount shows in September 1955, called his “First Anniversary Rock ‘n’ Roll Party,” he broke the all-time record gross take for both the Brooklyn and New York Paramount Theaters with a gate of $178,000 (for an eight day run). This topped the previous high that had been set by the Dean Martin-Jerry Lewis comedy team some years earlier when they reached the $147,000 mark at the New York Paramount. Among those performing at this show were: Red Prysock and his band, The Cardinals, The Rythmettes, Nappy Brown, The Four Voices, The Harptones, Chuck Berry (doing “Maybellene”), the Nutmegs, Al Hibber, Lillian Briggs and others.

Wrote one Cash Box reporter who covered the show:

1950s: The Brooklyn Paramount’s electric marquee at night announcing an Alan Freed show and star participants.

“…This reviewer has been through the teen age hysteria that existed from 1936 through 1945 when the kids danced in the aisles to the music of Benny Goodman, Frank Sinatra, Tommy Dorsey and others, but never have these eyes seen fanatical exuberance such as the type displayed at Alan Freed’s sensational 1st Anniversary Rock ’n roll program…”

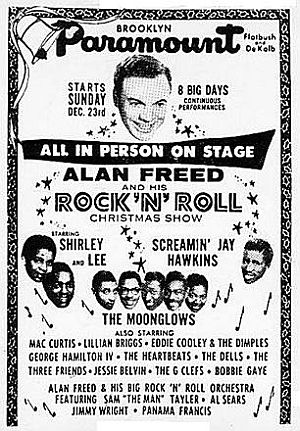

In December 1956, during an eight-day stretch over the Christmas holiday, Freed threw his “Rock ’n Roll Christmas Show” at the Brooklyn Paramount with a line-up that included: the Drifters, Fats Domino, Joe Turner, and others. All the musicians were black, but at least half the audience packing the arena was white.

Print ad for one of Alan Freed’s Christmas Shows running over 8 days at the Brooklyn Paramount, 1950s.

Back home, meanwhile, Freed’s radio show was also having an influence on emerging U.S. artists. Fred Bronson, writing in Billboard’s Hottest Hot 100 Hits, offers the following account of how Freed’s show had an impact on the formation of one of the more successful “girl groups” of the late 1950s:

…Arlene Smith was the leader of the Chantels, and her inspiration for forming her girl group was a man – or rather, a teenage boy. “Alan Freed came on the radio and played Frankie Lymon & the Teenagers singing ‘Why Do Fools Fall in Love,’” Smith told Charlotte Greig in [her book] Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow? “It was a lovely high voice and a nice song. Then Freed announces that Frankie is just 13! Well I had to sit down. It was a big mystery, how to get into this radio stuff… It seemed so far removed, but I made a conscious decision to do the same.

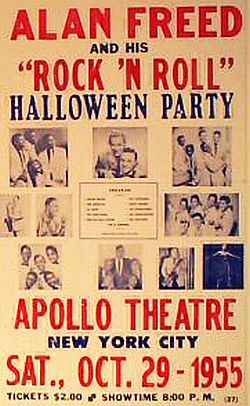

October 1955 poster for an Alan Freed show at the Apollo Theater in New York City.

When Frankie Lymon played a theater in the Bronx, Arlene took her group to meet Richard Barrett, Lymon’s manager. Backstage, the Chantels sang one of Arlene’s songs, “The Plea.” Barrett liked them enough to tell record company owner George Goldner that he wanted to sign them. Their first release was “He’s Gone” on Goldner’s End label; it peaked at No. 71. Their next single, “Maybe,” went to No. 15.

Within the space of five years or so, Alan Freed had helped move the rhythm and blues sound to a more prominent presence in pop and mainstream music. By early 1956, the music industry was advertising “rock ’n roll” records in the trade papers. A quote attributed to Freed from February 1956, has him explaining the new music: “Rock ’n roll is really swing with a modern name. It began on the levees and plantations, took in folk songs, and features blues and rhythm. It’s the rhythm that gets to the kids – they’re starved of music they can dance to, after all those years of crooners.” Freed had also become a champion of teenage kids and their musical interests, and a kind of middleman in the fight against those who wanted to ban the music seeing it as an influence on “juvenile delinquency,” a worrisome social problem and political issue at the time.

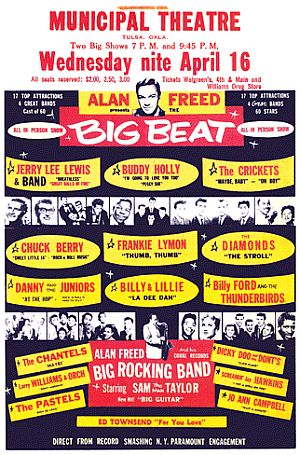

In 1957, while working for WINS, Freed continued hosting his big revues in the New York area and elsewhere. In Calgary, Ontario, for example, Freed’s “The Biggest Show Of Stars For 1957” played at the Stampede Corral venue. Performers included Fats Domino, Chuck Berry, Buddy Holly and the Crickets, the Everly Brothers, Paul Anka, Clyde McPhatter, Eddie Cochrane, Buddy Knox, Frankie Lymon, LaVern Baker, and The Drifters. Tickets were just $2.50. The show also played in the Canadian cities of Edmonton and Regina the next two nights.

By September 1957, Freed was a popular figure in the music industry, and during that month he hosted a big industry bash at his “Greycliffe” residence in Stamford, Connecticut. Among music label executives attending the gathering were: Bob Thiele of Coral Records; Sam Clark of ABC-Paramount; Morris Levy and Joe Kolsky of Roulette Records; and Jerry Wexler, Herb Abramson and Ahmet Ertegun of Atlantic. Alan Freed by this time, wasn’t limiting his exposure to the music industry via radio and TV. He was also involved with bringing rock ’n roll music to film.

|

“Rock ’n Roll Films”

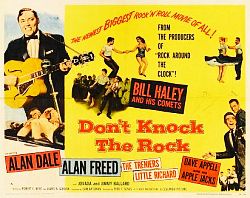

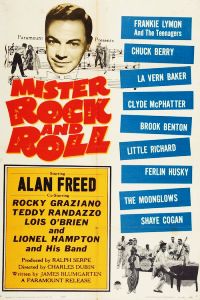

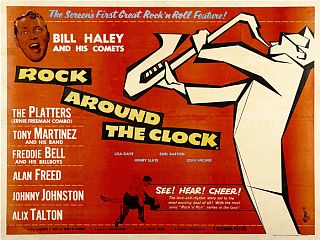

Poster for the 1956 film, “Rock Around The Clock,” billed as “The Screen’s First Great Rock ’n Roll Feature!” Click for 2-film DVD. That early combination of rock ’n roll music with a movie also caught the attention of Hollywood promoters — and DJ Alan Freed wasn’t far behind. But Hollywood first came to Freed, seeing him and his radio platform as a marketing vehicle. “…Deejays out of town were picking up on whatever Freed did,” explained Paul Sherman, who worked with Freed in New York. “What Freed played, they played, what Freed hyped, they hyped…” So Freed agreed to take a part in a film called Rock Around the Clock. In making the deal, Freed at first wanted cash up front, but was persuaded to consider taking only a little money up front and a percentage of the box office. That turned out to be a good deal for Freed later on, or as Paul Sherman remembers: “They could have bought Freed for $15,000, and instead [with the percentage arrangement] he made a fortune.”  Scene from “Rock Around The Clock” with Bill Haley, center, plaid shirt & Alan Freed, upper right. Click for Haley story. In addition to Bill Haley, a number of performers appear, including the Platters, Tony Martinez and band, and Freddie Bell and His Bellboys. The film also marked the screen debut of Alan Freed, who plays a disc jockey who books the Haley group in a venue that gives them the exposure and notice they need to break through. Rock Around The Clock – which became one of the major box office successes of 1956 – was shot primarily to capitalize on the popularity of Bill Haley’s multi-million-selling hit song, “Rock Around the Clock.” The Haley hit is heard on at least three occasions in the film, along with 17 other songs. The film was produced by B-movie king Sam Katzman, who would later produce several Elvis Presley films in the 1960s. It was directed by Fred F. Sears and distributed by Columbia Pictures. That same year, Katztman, Sears and Columbia teamed up for what they hoped would be an equally successful sequel, Don’t Knock the Rock, which also featured Bill Haley and Alan Freed. Rushed into production, the film premiered in December 1956 hoping to capitalize on Rock Around the Clock. The sequel’s storyline featured a rock star who returns to his hometown to rest up for the summer, but finds instead that rock ’n roll has been banned there by disapproving adults. Disc jockey Alan Freed and Bill Haley and his band, set about to show the adults that the music isn’t as bad as they think. The 85-minute film included 17 songs, several again from Haley, but also “Long Tall Sally” and “Tutti-Frutti” from Little Richard. Don’t Knock the Rock failed to duplicate the earlier film’s success, though it did help popularize Little Richard.The following year, two more rock ’n roll films were made involving Freed. Rock, Rock, Rock, was a black-and-white motion picture featuring performances from a number of early rock ’n roll stars, such as Chuck Berry, LaVern Baker, Teddy Randazzo, The Moonglows, The Flamingos, and The Teenagers with Frankie Lymon as lead singer. The film’s story line has teenager Dori Graham, played by then 13-year-old Tuesday Weld, who can’t convince her father to buy her a strapless gown for the prom and has to find the money herself in time for the big dance. The voice of Dori for her songs, was not Tuesday Weld’s, but that of singer Connie Francis. David Winters who would later appear in West Side Story, is also in the film. And Valerie Harper, later of Rhoda TV fame from a Mary Tyler Moore Show spin off, made her film debut in the prom scene of Rock, Rock, Rock. Alan Freed makes an appearance as himself in the film, telling the audience that “rock and roll is a river of music that has absorbed many streams: rhythm and blues, jazz, rag time, cowboy songs, country songs, folk songs. All have contributed to the big beat.”Another film in this same genre that also came out in 1957, Mister Rock and Roll, features Freed, professional boxer Rocky Graziano, and a number of musical artists, including: Teddy Randazzo, Lionel Hampton, Ferlin Husky, Frankie Lymon, Little Richard, Brook Benton, Chuck Berry, Clyde McPhatter, LaVern Baker, and Screamin’ Jay Hawkins.

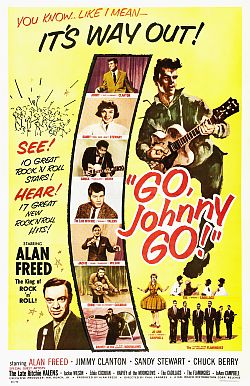

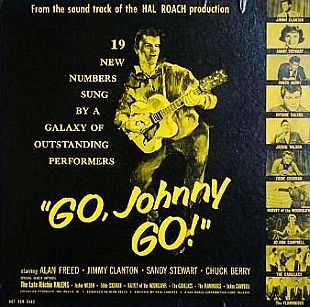

“Go, Johnny Go!” Go, Johnny Go! was a 1959 rock ’n roll film in which Alan Freed played a talent scout searching for a future rock ’n roll star. Co-starring in the film were Jimmy Clanton, Sandy Stewart, Chuck Berry, Jackie Wilson, Ritchie Valens, The Cadillacs, Jo-Ann Campbell, The Flamingos, Harvey Fuqua, and others. The filming of Go, Johnny Go!, according to Chuck Berry, was completed in five days in early 1959 in Culver City, California at the Hal Roach Studio. The 75- minute film premiered in Los Angeles October 7, 1959. The film’s title was inspired by Jimmy Clanton’s popular single “Go, Jimmy Go” as well as the refrain from Chuck Berry’s hit song, “Johnny B. Goode,” which was listed as “Johnny Be Good” in the onscreen credits. The song is sung by Berry over the opening and closing credits.In the film, as summarized by Turner Classic Movies (TCM), Freed, plays a kind of hipster father figure trying to give talented young people the musical exposure they need to become successful. Johnny Melody, played by Jimmy Clanton, is the troubled teen whose potential musical career Freed helps direct and save. In this tale, Clanton/Melody rises from rags to riches via a demo disc played on Freed’s radio show. Freed plays himself in the film, as does Chuck Berry. Yet the plot, like most films in this genre, is thin, and puts a cleaned-up face on rock ‘n roll. Still, it does provide a look at the fledgling music industry of that time and its early hype.  Screen shot from "Go, Johnny Go!" shows Alan Freed on drums behind Chuck Berry on guitar. Ritchie Valens, at age 18, has a cameo singing appearance in the film. However, Valens would die in a plane crash along with Buddy Holly and the Big Bopper on February 3, 1959, several months before the film was released. Go, Johnny Go! also marked the final screen appearance of “rockabilly” performer Eddie Cochran, who died in an automobile crash on April 17, 1960.  Cover of LP sound track album for the film, “Go, Johnny Go!,” with 19 song from the film, issued in early 1959. Click for CD. TCM’s reviewer, meanwhile, noting the film’s “crude fictionalizing and dreadful miming,” did find some redeeming value. Go, Johnny Go! “offers the only moving evidence of Ritchie Valens,” he observes, and also includes “a rare fragment of Eddie Cochran.” The film also shows the Cadillacs doing two “Coasters-like” numbers, and has Chuck Berry “struggling to be a nice guy in a ‘major acting role’.” This film might have been better, he concludes, if it merely undertook to be a concert film or a documentary. But the “pretense of plot” made it pretty superficial. Go, Johnny Go!, in any case, was the final film foray of Alan Freed in those years, as not long after, Freed became embroiled in the radio “payola” scandal that ended his career. |

Controversy

In 1957, Alan Freed briefly had his own ABC-TV dance show. He is shown here at center, with Jackie Wilson, far left, and Jimmy Clanton, left of Freed, and others.

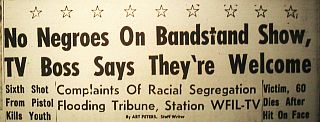

Headlines from a May 1958 Boston Globe story spell trouble for Alan Freed’s stage shows.

“Payola”

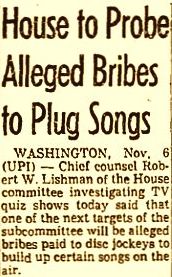

Nov 1959: Newspaper headline from story on payola hearings.

In 1959, a star contestant on the TV quiz show Twenty-One, named Charles Van Doren – who had become a national sensation for his assumed brilliance on the show – admitted later that he was given the correct answers beforehand.

Congress had a field day with the TV “quiz show” scandals, and then turned to the radio industry where a new kind raucous “rock ’n roll” music was shaking up the established order — and some thought, fueling juvenile delinquency as well.

But the main focus of the Congressional interest in the music business was something called “pay-for-play,” where radio DJ’s were being paid cash or given other favors by music industry reps for repeated playing or “plugging” of songs to boost their appeal and sales. This practice was given the name “payola,” a contraction derived from the words “payment” and “Victrola.”

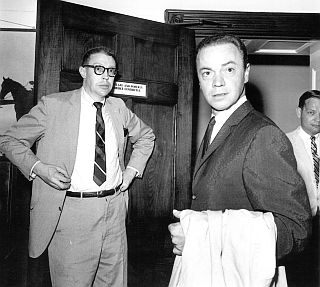

Alan Freed, center, going into closed-door hearings before a U.S. House of Representatives committee investigating “payola” in the American radio business, April 25, 1960.

In early 1960, hearings began, and some twenty-five witnesses would be called, including Clark and Freed, the presidents of several of the country’s larger radio stations, representatives from Billboard magazine, and others. Freed testified in a closed-door session in April 1960. But Freed had already made some public statements that did him little good as he stepped into the national spotlight: “What they call payola in the disc jockey business,” he is reported to have said at one point, “they call lobbying in Washington.”

At the time of the hearings, however, payola wasn’t a crime in most states, and many in the industry seemed to regard it as an accepted practice. Before it was all over, the U.S. House Oversight Committee, in both closed-door and open sessions, heard from some 335 disc jockeys from around the country who admitted to having received over $263,000 in “consulting fees.” But that number was likely low, since one DJ, Phil Lind, from Chicago’s WAIT, indicated he once received $22,000 to play a single record.

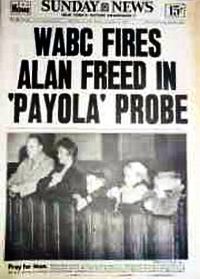

NY Sunday News runs front page story about Alan Freed‘s firing by WABC radio over “payola,” September 1960.

Other DJs and promoters involved in payola suffered similar results, but many made it through the proceedings with only minor damage. Freed’s rising prominence on the national scene, however, made him a prime target. And in the wake of the payola probes, there was also some impact on the music itself, if only temporary.

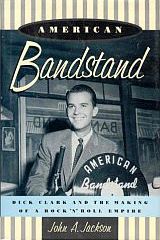

“One of the results of the payola scandal was the change in radio,” explains John Jackson in his book, Big Beat Heat – Alan Freed and the Early Years of Rock ’n Roll. “WINS radio in New York dropped rock ’n roll and played Frank Sinatra three days straight. Other stations dropped rock. Disc jockeys no longer could chose songs and play what they wanted. The station play list came in. And music became bland.”

|

“Boom-to-Bust” Over the years, as Alan Freed’s fame rose, his income also soared, sometimes in ways not generally known at the time. One way to promote new songs was to add a popular DJ’s name to the record’s label as a “song publisher,” which would give the DJ a share of the royalties from that song and also incentive to play the song. Alan Freed, although not a song author, became a co-publisher of several hit songs. Freed received writing credit, for example, on Chuck Berry’s “Maybellene,” a million-seller; on the Moonglows’ “Sincerely,” a No. 20 hit in 1955; and several others. Recording labels like Chess Records would put DJs’ names on the songs to get airplay and this amounted to form of a payola. Still, author John Jackson, who has written about Freed and the 1950s music industry, says Freed pushed songs like “Maybellene” because he believed in them, and that he also pushed other Chuck Berry records – and those of many other artists – just as hard, even though he had no co-writing or publishing involvement in any of them. Alan Freed also did well with his rock ‘n roll stage shows, taking a piece of the gate for each show. And he sold record albums, had a recording label, and a band of his own for a time – each of which also provided him with income. Still, as the rock ’n roll “riots” and payola scandal both ensnared Freed around the same time, his legal costs soared, his fame sank, and his income dried up, leaving him in dire financial straits in his final years. Even after his death, the IRS attached royalty payments from Freed’s BMI records for 12 years to satisfy its income tax judgement against him. |

Alan Freed, meanwhile, tried to pick up the pieces of his shattered career and move on. In 1960, after leaving New York, he was hired by Los Angeles radio station KDAY – a station owned, ironically, by the same company that owned WINS. But shortly after starting at KDAY, Freed was called back to New York when a grand jury there handed down commercial bribery charges against him that dated back some ten years. In May 1960, he and seven other radio DJs were arrested and booked in Manhattan, charged with receiving a total of $116,850 in payola. The final verdict in Freed’s case wouldn’t come for another few years.

Back at KDAY, meanwhile, Freed had signed an agreement to steer clear of payola, and he jumped back into his DJ persona and musical passion, helping showcase new songs and artists, such as Kathy Young & the Innocents and their hit-to-be, “A Thousand Stars.” Freed was also planning to continue his live concerts in the L.A. area, this time eyeing the Hollywood Bowl as a choice venue for the live shows. KDAY, however, would not permit Freed to promote or stage his concerts, and with that, he quit the station and returned to New York. At the time, Chubby Checker’s hit song “The Twist” had caught on nationally spurring a new dance fad, and Freed hosted a live twist show for a time in New York. But as the twist rage faded, Freed left New York and began working at WQAM radio station in Miami, Florida, a job which lasted about two months.

By 1962, Freed was back in New York dealing with his commercial bribery trial. He was eventually charged with 26 counts of commercial bribery. In December 1962, he plead guilty to 2 counts, received a suspended sentence, and paid a fine of $300.00. Facing mounting legal bills for that fight, Freed then faced Federal charges of income tax evasion in 1964. By then, he was living in Palm Springs, California and drinking heavily. On New Year’s day 1965, he entered a Palm Springs hospital for gastrointestinal intestinal bleeding, resulting from cirrhosis of the liver. He died twenty days later of kidney failure. He was 43 years old.

Poster for 1978 film about Alan Freed and early days of rock ’n roll, “American Hot Wax.” Click for poster.

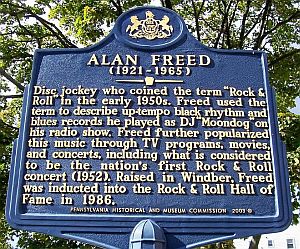

In 1986 Freed was among the original inductees to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland – located there partly due to Freed’s influence on early rock ’n roll. In 1988, he was also posthumously inducted into the National Radio Hall of Fame.

In 1991, a “star” for Alan Freed was added in his name to the Hollywood Walk of Fame, the same year John Jackson’s biography of Freed was published – Big Beat Heat: Alan Freed and the Early Years of Rock & Roll.

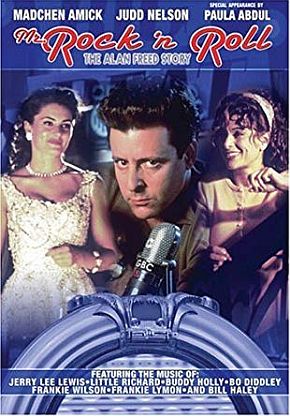

In 1999, another attempted film on Freed, this one for TV, titled Mr. Rock N Roll: The Alan Freed Story, with Judd Gregg as Freed, received a lukewarm reception, but still has a following.

Freed’s story is perhaps best told, however, at AlanFreed.com, a nicely assembled website managed by some of his surviving family, including a number of children and grandchildren. The site is highly recommended for those who want to see original news sources and other material. In addition to the other awards and inductions already mentioned, in February 2002, Freed was honored at the annual Grammy awards show with a Trustees Award, given to “individuals who, during their careers in music, have made significant contributions, other than performance, to the field of recording.” And last but not least, the mascot of the Cleveland Cavaliers professional basketball team is named “Moondog,” in honor of Freed.

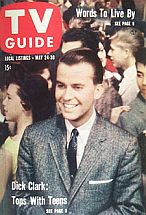

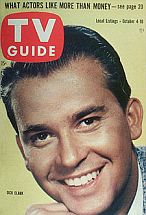

See also at this website, for example, “Bandstand Performers, 1963″ a story profiling and listing some of the musical guests who appeared on Dick Clark’s ‘American Bandstand’ TV dance show that year from Philadelphia, or, “Elvis Riles Florida, 1955-56,” a story profiling Elvis Presley in Jacksonville, Florida where he faced an arrest warrant if he “gyrated” too suggestively on stage. Additionally, the topics page, “Pop Music 1950s,” includes links to more than 20 stories on songs and artists from that era, and the “Annals of Music” page offers a broader selection beyond that.

Thanks for visiting — and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research and writing at this website. Thank you. — Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

____________________________________

Date Posted: 28 February 2014

Last Update: 16 April 2024

Comments to: jackdoyle47@gmail.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Moondog Alan Freed: 1951-1965,”

PopHistoryDig.com, February 28, 2014.

____________________________________

Alan Freed at Amazon.com…

Sources, Links & Additional Information

Alan Freed at WAKR radio in Akron, Ohio, mid-1940s. |

Hartford Times (CT) newspaper story announcing a forthcoming January 1958 Alan Freed stage show. |

1958: Alan Freed, going through a stack of 45rpm records at WABC radio station in New York. |

Poster ad for an Alan Freed “Big Beat” stage show of April 16, 1958 for the Municipal Theater of Tulsa, OK. |

Alan Freed in the 1950s, likely hosting a live stage show in the New York city area, broadcast over WINS radio. |

Pennsylvania historic marker honoring Alan Freed at location of his boyhood years in Windber, PA. |

8 Sept 1957: From left, Alan Freed, Larry Williams, Ben Dacosta (DJ) & Buddy Holly at NY Paramount Theater. |

Judith Fisher Freed, “The Alan Freed Web- site,” AlanFreed.com.

John Morthhland, “The Rise of Top Forty A.M.,” in Anthony DeCurtis, James Henke, Holly George-Warren, and Jim Miller (eds.), The Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock ‘n’ Roll, New York: Random House, 1992, pp.102-106.

David Halberstam, The Fifties, New York: Villard Books, 1993, pp. 466-467.

Ben Fong-Torres, “Biography,” Alan Freed .com.

John A. Jackson, Big Beat Heat: Alan Freed and the Early Years of Rock & Roll, Schirmer Books, 1991.

“Archives: Moondog (1950-1954),” Alan Freed.com.

Hank Bordowitz, Turning Points in Rock and Roll, New York: Citadel Press/Kensington Publishing, 2004, pp. 60-68.

“Alan Freed,” Wikipedia.org.

“Disc Jockey Alan Freed Files in Bankruptcy,” The Plain Dealer (Cleveland, Ohio), May 9, 1951.

“Moondog Coronation Ball,” Entertainment: This Day in History, History.com, March 21, 1952.

“Warrants Sought in Blues Ball Brawl,” The Plain Dealer (Cleveland, Ohio), March 22, 1952.

“Moon Doggers Get New Permit for Ball,” The Plain Dealer (Cleveland, Ohio), May 12, 1952.

“Moon Dog Dance To Be Restricted; City of Fire Prevention Rules Threaten Frolic,” The Plain Dealer (Cleveland, Ohio), December 12, 1952.

“Moondog Bark Worse Than Bite; Only 500 at Dance,” The Plain Dealer (Cleveland, Ohio), December 15, 1952.

Marv Goldberg, “The Clovers – Part 1,” Marv Goldberg’s R&B Notebooks, 1999/2009.

Tom O’Connell, “Alan Freed Hosts Moondog Affair Tonight in Newark,” The Plain Dealer (Cleveland, Ohio), May 1, 1954.

George E. Condon, On The Air, “‘King of the Moondogs’ Quits WJW to Sign with New York Station,” The Plain Dealer (Cleveland, Ohio), August 1954.

“Dear Mr. Moondog: Alan Freed’s Coronation Ball Packs 11,000 Into Newark Armory,” Our World, August 1954.

“Record Crowd of 9,000 Fans Attend Public Hall Rhythm and Blues Show,” Cleveland Call & Post, August 15, 1954.

Josephine Jablons, “‘Moondog,’ Blues, Jazz Disk Ace, Gets NY Show,” New York Herald Tribune, August 1954.

Tom O’Connell, “Alan Freed, WJW Battle Over Moon Dog Rights,” The Plain Dealer (Cleveland, Ohio), September 11, 1954.

“Rock ‘n’ Roll Ball,” The Cash Box, January 29, 1955.

“Alan Freed’s ‘Rock-n-Roll’ Music Thrills New Yorkers: Former Salem Man Rises as Disc Jockey” (Salem, Ohio news source), January 1955, via AlanFreed.com.

“$155,000, One Week’s Gross – Paramount Theater, Brooklyn, New York,” Variety, Wednesday, September 14, 1955.

Robert Sullivan, “Rock ‘n’ Roll – ‘n’ Riot,” Sunday News (New York), September 18, 1955.

“Alan Freed Rocks ’n Rolls To The Tune of $178,000 Gross For One Week Stand At Brooklyn Paramount,” The Cash Box, 1955.

“Rock Around the Clock (film),” Wikipe-dia.org.

Alan Freed, “The Big Beat,” Guest Writer, Izzy Rowe’s Notebook, The Pittsburgh Courier, 1955.

“Music: Yeh-Heh-Heh-Hes, Baby,” Time, Monday, June 18, 1956.

Milt Freudenheim, “Alan Freed Cashes In On 2R’s,” The Cleveland Press, Saturday, April 13, 1957, p. 38.

Earl Wilson, “Alan Freed, Rock ’n Roll Exponent, Boosting Rock- a-Billy in Gotham,” The Plain Dealer (Cleveland, Ohio), April, 13, 1957.

“Alan Freed Pacted For Six Week Tour,” The Cash Box (New York), November 16,1957.

Associated Press, “New Haven Shall Not Be Freed, Court Rules,” The Plain Dealer (Cleveland, Ohio), May 8, 1958.

“Television: Rock ’n Riot,” Time, Monday, May 19, 1958.

“Alan Freed Quits Radio Station in Rock ’n Roll Row,” Long Island Press (Jamaica, NY), May 9, 1959.

Walter Ames, “L.A. Jockeys Deny Payola, But Admit Offers,” Los Angeles Times, Nov. 24, 1959.

“Dick Clark Will Face Payola Probers; Alan Freed Will Also Testify,” Los Angeles Evening Mirror- News, November 24, 1959, p. 1.

“Show Business: Facing the Music,” Time, Monday, November 30, 1959.

“Disc Jockeys: Now Don’t Cry,” Time, Monday, December 7, 1959.

“Archives: Payola (1959-1962) – Press Coverage,” AlanFreed.com.

United Press International (UPI), “Interest-Free Loan to Alan Freed Told,” December 1, 1959.

“Alan Freed ~ On The Record,”GeoCities.

“Rock, Rock, Rock,” Wikipedia.org.

Jeff Stafford, “Go, Johnny, Go! (1959),” Articles, TCM.com.

“Go, Johnny, Go! (1959),” Notes, TCM.com.

“A Tribute to Alan Freed, Mr. ‘Rock ‘n’ Roll’,” RockaBillyHall.com.

Bill Millar, “Alan Freed: Mr Rock ’n Roll,” The History of Rock, 1982 @ TeachRock.org.

Wes Smith (Robert Weston), The Pied Pipers of Rock ‘N’ Roll: Radio Deejays of The 50s and 60s, Longstreet Press, 1989.

Jane Scott, “Triumphs and Tragedies of the Legendary Alan Freed,” The Plain Dealer

(Cleveland, Ohio), Friday, September 27, 1991.

Roger Brown, “King of the Moondoggers: Celebrating Alan Freed, The DJ Who Named Rock ‘n’ Roll,” The Plain Dealer (Cleveland, Ohio), 1995.

Robert Fontenot, “It’s Not Goodbye, It’s Just Good Night: The Payola Scandal of 1959,” About.com.

“Alan Freed R.I.P. Rock N Perpetuity,” Artie Wayne, March 10, 2007.

B. Goode, Review, “Rock Around the Clock,” Gonna Put Me in The Movies (blog), August 22, 2010.

B. Goode, Review, “Don’t Knock the Rock,” Gonna Put Me in The Movies (blog), August 25, 2010.

“Leo Mintz, A Cleveland Rock ‘n Roll Founding Father, Celebrated at Rock Hall,” Cleveland Magazine, Thursday, September 2, 2010.

Lance Freed, Special to The Plain Dealer, “2012 Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Inductions: Moondog Memories from Alan Freed’s Son, Lance Freed – Cleveland, 1952,” Cleveland.com, March 31, 2012.

Stephen Metz, “Alan Freed – *The Legend*,” Stephen Metz, February 6, 2013.

Lydia Hutchinson, “Alan Freed and the Radio Payola Scandal,” Performing Songwriter .com, November 20, 2013.

An Ohio Historical marker located just outside the Rock ’n Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, commemorates Alan Freed’s contributions to rock ’n roll and also notes that he was a “charter inductee” at the Hall (1986).