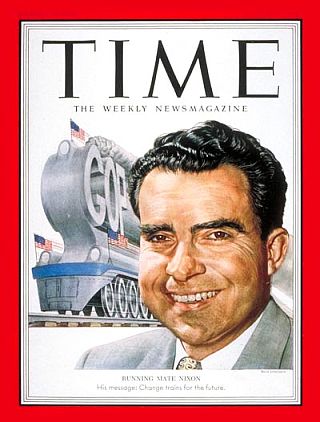

Time magazine cover of August 25, 1952 features Republican vice presidential candidate Richard Nixon in a flattering feature story a few weeks before “secret Nixon fund” reports emerged.

Eisenhower, or “Ike” as he was known, was the popular military general who had been Supreme Allied Commander during the critical D-Day landing of World War II.

Richard Nixon was a young rising political star from California who had been elected to Congress in 1946, and made a name for himself as an aggressive anti-Communist serving on the House Un-American Activities Committee.

Four years later at age 38, he was elected to the U.S. Senate. There he became an outspoken critic of President Truman’s conduct of the Korean War and wasteful spending by the Democrats. Nixon was then regarded as a good choice to run with Eisenhower.

So in the fall of 1952, with six weeks to go until the national elections, the Republicans appeared to be set with their ticket.

But then on September 18th, 1952, the New York Post ran the front-page headline: “Secret Nixon Fund,” with a detailed story and second headline inside the paper that read: “Secret Rich Men’s Trust Fund Keeps Nixon in Style Far Beyond His Salary.” The newspaper story charged that wealthy Californians had given $18,235 (about $170,000 in today’s money) to a secret campaign fund for Nixon in return for political favors. Other newspapers soon picked up the story.

1952 Vice Presidential candidate Richard Nixon with family dog, ‘Checkers,’ among campaign gifts which Nixon sought to explain in his famous, nationally-televised September 1952 speech.

The New York Herald Tribune called on Nixon to withdraw from the Republican ticket. Some Republican party leaders asked him to resign.

The secret fund, in turned out, was for political purposes and was perfectly legal. But the impression created by the stories was that Nixon was on the take; being paid to do the bidding of special interests.

Eisenhower was not happy with the story, having been critical of the Truman Administration for corruption during the campaign. Privately, it was said that Ike thought it might be a good thing if Nixon took himself off the ticket. But others, including Nixon supporter and former New York governor and presidential candidate Thomas Dewey, suggested that Nixon use the new medium of television to respond to the charges. Eisenhower agreed, advising Nixon: “Tell the country everything you have ever received, how much money you have earned, what it’s been used for, what your worth is.”

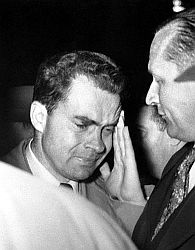

Nixon in some consternation after September 1952 meeting with Ike. Senator William Knowland is at right.

Nixon hired an advertising agency to help produce the live broadcast. The ad agency brought in soap opera directors from Hollywood for advice and also rounded up the best make-up artists and prop men to assist with the broadcast.

The speech was broadcast nationwide on September 23, 1952 from the El Capitan Theater in Hollywood where TV stage crews built a mock middle-class den with desk and fake library as part of the set. Nixon would address a combined TV and radio audience that included a network of some 64 NBC television stations, 194 CBS radio stations, and the 560 stations in the Mutual Broadcasting network.

In 1952, about 40 percent of the nation’s homes had television sets and about 80 percent had radios. It would be one of the first political uses of television to appeal directly to the populace.

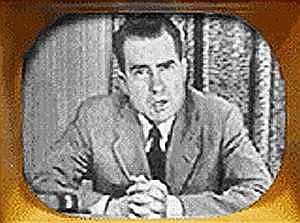

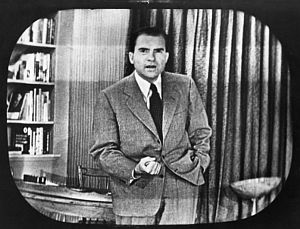

Richard Nixon during his nationally-televised Checkers speech. |

Nixon’s wife, Pat, on the set during speech, was also shown in some camera shots. |

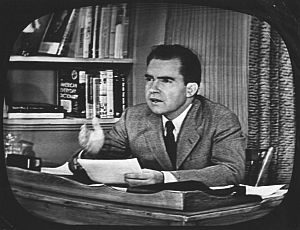

Richard Nixon seated at his studio-made office during his Sept 1952 “Checkers” speech. |

Nixon standing during his televised Checkers speech, when at one point he would say 'I'm not a quitter'. |

The Speech

In the speech, Nixon began seated at a desk, with his wife Pat nearby, sitting in a parlor chair. The camera focused mostly on Nixon, who also stood up and walked close to the desk at one point.

In his talk, Nixon made clear that he “wasn’t a rich man,” laying out some family history, describing his father’s grocery store and his own experiences working his way through law school. Nixon denied any wrongdoing with regard to the fund, citing an independent audit that cleared him of any malfeasance. The money, he asserted, did not come to him as income, but rather as reimbursement for expenses.

Nixon also gave a complete financial history of his personal assets, finances and debts, including his mortgages, life insurance, and loans. He went into great personal detail, saying for example, he owned a 1950 Oldsmobile, had two houses with mortgages, and was making regular payments on a $3,500 loan from his parents. This litany painted Nixon and his family as living an austere lifestyle.

“Well, that’s about it,” he said, summing up the financial disclosures. “That’s what we have and that’s what we owe. It isn’t very much, but Pat and I have the satisfaction that every dime that we’ve got is honestly ours. I should say this — that Pat doesn’t have a mink coat. But she does have a respectable Republican cloth coat.”

Then came the Checkers part of the speech, which Nixon would later say came from his memory of Franklin Roosevelt’s swipe at a critical press corps who were attacking his dog, Fala. Checkers was given to Nixon as a gift, as he explained during his televised speech:

“One other thing I probably should tell you…. We did get something — a gift — after the election. A man in Texas heard Pat on the radio mention the fact that our two youngsters would like to have a dog. . . . We got a message from the Union Station in Baltimore saying they had a package for us. . . . You know what it was? It was a little cocker spaniel in a crate. . . . Black and white, spotted. And our little girl, Tricia, the six year old, named it Checkers. And you know, the kids, like all kids, love the dog and I just want to say this right now, that regardless of what they say about it, we’re gonna keep it.”

Nixon also turned the speech back on the Democrats, and challenged Democratic Presidential candidate Adlai Stevenson to give a similar public account of his finances. He also attacked alleged corruption in the Truman administration and labeled Truman’s foreign policy a failure that had led to the Korean War. He ended by appealing directly to the public, urging his listeners and viewers to telegraph or write the Republican National Committee on whether he should remain the Vice-Presidential nominee.

When the speech ended it was unclear what the response would be, though there were reportedly some in the studio who were moved to tears over Nixon’s “plain folks” disclosures and the Checkers story. Nixon himself thought he had failed. However, he did get an early telephone call from Hollywood movie producer Daryl Zanuck giving his speech a rave review. But the national press was not as generous. Nixon, said the New York Post, had indulged in “a private soap opera” in which “the corn overshadowed the drama.” The New York Times charged that Nixon made no acknowledgment “that he had made any sort of mistake in accepting these funds in the first place.” The nation’s voters, however, reacted much differently. They were moved by Nixon’s distress and his candor.

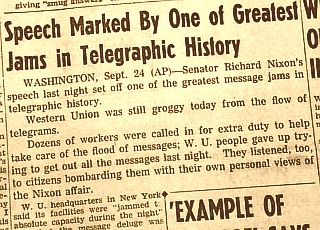

Newspaper report on overwhelming telegram response to Nixon's Checkers speech and his appeal to voters for their help.

Nixon with wife Pat, two daughters & their dog, Checkers.

Halberstam on Nixon

Journalist David Halberstam, writing years later about the Checker’s speech in his book The Powers That Be, made the following observations about the speech and how it changed Nixon’s thinking about the national media. Halberstam relies here on one of Nixon’s aides, Ted Rogers, who had worked with Nixon since the days of his 1950 Senate campaign:

. . .On the famous Checkers speech, . . .Rogers had his doubts about putting Pat Nixon on [the set] that night, thinking it might be improper. But Nixon insisted. It was, Rogers thought, as if it were the Nixons against the world. In her husband’s mind, her honor and reputation had been attacked just as his own had been. Rogers had no idea what Nixon was going to say that night, and when the speech was over, with Nixon bursting into tears at the end, deeply moved by his own words, Rogers, like many others, thought it masterful. It had clearly saved Nixon’s place on the ticket, and it had turned the flow of the campaign around.

But there were doubts about it later. It was as if somehow in saving himself, Nixon had paid too high a price. He had made himself even more the issue — not his politics, but himself. . . . From then on. . . Nixon became an electronic candidate. . . . [H]e did not care much about the writing press. . . He had done it his way, with no impertinent questions and answers at the end. Suddenly, television was magic. . . . There was a growing feeling among the political and journalistic taste makers of the country that Nixon was not quite acceptable for very high office. He had gone just a little too far. (The taste makers sensed that perhaps Dwight Eisenhower shared their opinion, although Ike welcomed Nixon back on the ticket.) . . . .

There was something else that Rogers noticed about the Checkers speech — the powerful impact it had, not just on the nation and not just on Eisenhower, but on Nixon himself. From then on, as far as Rogers was concerned, Nixon became an electronic candidate. He had an immediate consciousness of the power of television. From then on, he did not care much about the writing press (though he liked reporters of all sorts less and less). He had done it his way, with no impertinent questions and answers at the end. Suddenly television was magic. Rogers, who liked much of the writing press, noticed immediately Nixon’s changed attitude toward reporters. Up until then he had been very cautious and solicitous in the care and feeding of reporters, and reasonably accessible. But from then on it changed. If the [campaign] bus was ready to roll and they weren’t there, he’d simply say, “F___ ’em, we don’t need them.” The Checkers episode had taught Nixon first that the national press was potentially antagonistic and harmful to him, personally, and second that he could go over their heads.”

Dwight D. Eisenhower & Richard M. Nixon on November 4, 1952, after winning the national election. (AP photo.)

See also at this website: “1968 Presidential Race, Republicans” (in- cludes Nixon’s run for the White House and role of celebrities in his and other campaigns); “The Frost-Nixon Biz, 1977-2009”( the media, publishing, film & theater business that grew up around the David Frost/Richard Nixon interviews); and “Enemy of the President, 1970s” ( includes Watergate political cartoons from Paul Conrad who appeared on Nixon’s “enemies list.”). See the Politics & Culture page for other story choices in that category. Thanks for visiting – and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research and writing at this website. Thank you – Jack Doyle

__________________________

|

Please Support Thank You |

Date Posted: 7 September 2008

Last Update: 21 August 2019

Comments to: jdoyle@pophistorydig.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Nixon’s Checkers’ Speech, 1952,”

PopHistoryDig.com, September 7, 2008.

_______________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

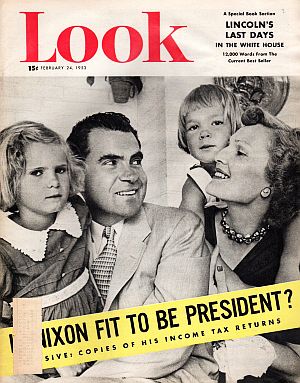

Feb 24th, 1953 issue of ‘Look’ magazine continued to raise questions about Richard Nixon, asking in a banner tagline across its cover, ‘Is Richard Nixon Fit to Be President?,’ also offering copies of his income tax returns. |

“Richard M. Nixon, Checkers Speech,” full text of speech @ AMDOCS: Documents for the Study of American History.

See American Rhetoric.com for full text of Nixon’s Checkers Speech and video excerpt.

See History.com video story on Nixon & his Checkers Speech narrated by Roger Mudd, which is preceded by short commercial and runs into other segments on the Nixon presidency.

“Nixon Blames Smear For Fund Revelation; Nixon Should Withdraw,” Washington Post, September 20, 1952, p. 1.

James Reston, “Eisenhower Backs Nixon on Ticket,” New York Times, Saturday, September 20, 1952, p. 1.

Edward T. Folliard, “Ike Wants to Know His Running Mate Is Morally Clear Before Closing Case,” Washington Post, September 21, 1952, p. M-1.

Associated Press, “Eisenhower to Make Up Mind After Nixon Speech Tonight,” Washington Post, September 23, 1952, p. 1.

Gladwin Hill, ” ‘I’m Not a Quitter’; Senator Says He’ll Let Republican National Committee Decide; Nixon Puts Fate Up to G. O. P. Chiefs,” New York Times, Wednesday, September 24, 1952, p. 1.

“Nixon Wires Swamp GOP,” Daily Mirror (NY, NY), September 25, 1952, p. 1.

“G. O. P. Heads Rally to Nixon’s Support; Summerfield Asserts Attack Has ‘Backfired’ — Senator’s Position Held Stronger,” New York Times, Thursday, September 25, 1952, p. 1.

Dent Williams, “Ike Declares Nixon Will Remain After Face-to-Face Meeting Here; City Roars Out Huge Ovation as General Says Nixon Okay,” Wheeling Intelligencer (Wheeling, West Virginia), September 25, 1952, p. 1.

James A. Hagerty, “Nixon’s Speech ‘Shot in Arm’ To the G. O. P., Survey Finds,” New York Times, Monday, September 29, 1952, p. 1.

“Nixon Family Turns Back Flood of Cash,” Washington Post, October 2, 1952, p. 3.

Drew Pearson, “Questions Nixon Hasn’t Answered,” Washington Post, October 30, 1952, p. 41.

David LaGesse, “The 1952 Checkers Speech: The Dog Carries the Day for Richard Nixon, U.S. News & World Report, usnews.com, January 17, 2008.

Joe Garner, Stay Tuned: Television’s Unforgettable Moments, Kansas City: Andrews McMeel Publishing, 2002, pp. 60-63.

“Richard M. Nixon: Checkers Speech,” Great Speeches Collection, TheHistoryPlace.com.

“Checkers Speech,” Wikipedia.org.

David Halberstam, The Powers That Be, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1979, pp. 330-331.

Sean Wilentz, “Pleading For Their Political Lives,” New York Times, August 24, 1998.

____________________

Return to Home Page