In May 2012, Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. was in Portland, Oregon speaking out about U.S. coal exports. He was there supporting an alliance of Pacific Northwest citizen groups worried about the impact of a developing “coal corridor” in their region. Some half dozen new export terminals were then proposed for the Pacific coast. Coal, headed to Asian markets from Western strip mines, would bring a daily disruption of long, coal-hauling unit trains through Northwest communities from Montana to Washington. More than 40 years earlier, in 1968, Kennedy’s father – Robert F. Kennedy, then U.S. Senator and former U.S. Attorney General – was visiting the coal mining communities of Eastern Kentucky. And before that, in 1960, his uncle – John F. Kennedy, then running for president – helped bring the spotlight on coal poverty in West Virginia. His other uncle, Ted Kennedy, a U.S. Senator, helped oversee coal mine safety regulations in the 1980-2000s period. What follows here is look back at some of that history – how these Kennedys and others from that Massachusetts family, have brought national attention to the plight of coal communities, coal miners and their families, and/or coal/environment issues.

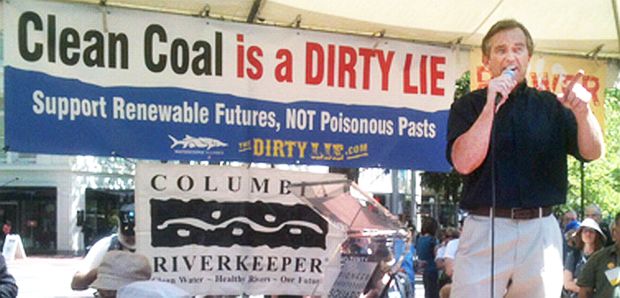

May 2012: Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., speaking at a Portland, Oregon rally opposing coal exports. More on his coal-related activism – from the 1990s through the 2010s – will be covered later in this article.

Early history in the Kennedy family, circa 1920s, indicate some investments and other ties to the coal industry. The paternal grandfather of JFK, RFK, and Ted Kennedy – Patrick J., or “P.J.” Kennedy, as he was called – had made an investment in the Suffolk Coal Company, an interest he held in 1929 at the time of his death. “PJ’s” son, Joseph P. Kennedy – father of JFK, RFK and Ted Kennedy – is reported to have made a killing in a 1922 stock deal ($45 million in today’s money by some estimates) speculating on Ford Motor Company’s acquisition of the Pond Creek Coal Co. in Kentucky. And Robert F. Kennedy’s wife, Ethel Skakel (married in 1950) was the daughter of multi-millionaire George Skakel who was a principal in The Great Lakes Coal & Coke Company of the 1920s.

Yet in subsequent generations, as members of the Kennedy family coursed through American politics, they became concerned with the hard lives of coal mining families and/or the unhappy side effects of coal mining, especially in Appalachia. During the mid-20th and early 21st centuries, Kennedy family members – while running for political office, acting on public policy matters once in office, or in various public service roles – worked to help coal miners, their communities and families, or to spotlight coal-related environmental problems and safety issues. First, consider John F. Kennedy in the early 1960s, who became the nation’s 35th president.

1960-1963

JFK & West Virginia

April 1960: JFK greets a one-armed miner near Mullens, WV while on the campaign trail for the West Virginia primary election. Photo: Hank Walker, Time/Life.

But in April 1960, Kennedy won the Wisconsin primary, beating rival Senator Hubert Humphrey of Minnesota. Kennedy’s victory was helped by Catholic voters in some districts. Yet, in many non-Catholic districts, Kennedy did not have a strong showing. That meant the next primary that year – in West Virginia, a state that was 95 percent Protestant – would be a more telling test of Kennedy’s non-Catholic appeal. But West Virginia was uncharted territory for Kennedy. As he had done elsewhere in the country in his early informal campaign, Kennedy had visited West Virginia a few times in 1958 and 1959. But now in 1960, ahead of the May 10th primary, he enlisted all the help he could find with friends and family members fanning out across the state to help him get his message out. JFK himself was also a tireless candidate, traveling throughout the rural state to visit voters wherever he could – though engaging voters directly was difficult due to that state’s rugged terrain.

But it would be West Virginia’s coalfields and coal towns – mostly in the southern part of the state – that would provide Kennedy with a new kind of political education and voter support that would help him gain the Democratic presidential nomination.

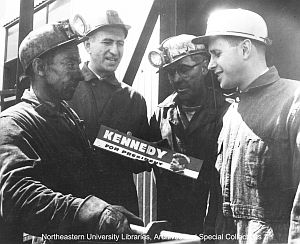

April 26th, 1960: JFK meeting with a group of coal miners during a shift change at the Pocahontas Fuel Company’s Itmann mine, near the town of Mullens, West Virginia, in Wyoming County. Photo, Hank Walker.

The coal industry then was in the midst of a pretty brutal downturn. No longer the primary fuel source for home heating, locomotive engines, or industrial factories – as oil and gas replaced coal in many of those uses – coal’s share of the nation’s energy supply had dropped precipitously, from 51 percent in 1945 to 23 percent in 1960. West Virginia’s coal production of 173 million tons in 1947 had fallen to less then 120 million tons by 1960. In addition, increasing mechanization of coal mining in the 1950s had wiped out tens of thousands of jobs. West Virginia’s coal miners – more than 116,400 in 1947 — had fallen to 42,900 in 1960. Local economies in more than 20 of the state’s 55 counties were hit hard. Some counties like Mingo and McDowell had 25-to-40 percent of their populations in need of paltry federal food packages (a minimal system then used prior to food stamps).

April 1960: JFK campaigning in rural West Virginia in advance of the state's May 10th primary.

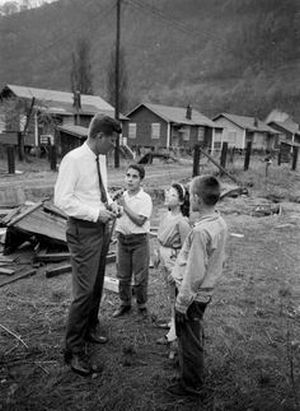

On April 6th, 1960, Kennedy spoke with coal miners at Slab Fork Mine in Raleigh County, a county that had experienced a 20 percent population decline between 1950 and 1960. Kennedy gathered with the miners near the mine entrance, shook hands, and answered questions from miners, holding a microphone between himself and the miners as the exchanges were being filmed by a local TV crew. Kennedy’s answers were crisp and made good sense, as he ticked off a list of several policy actions that could be taken to address coal-related economic issues of concern to the miners.

Kennedy also visited miners in the state’s southern-most county, McDowell – where coal mining dated to the early 1890s after the first rail lines came in. By the 1950s, McDowell had become the state’s leading coal producer, a prosperous place with a population of more than 100,000. Yet in 1960, when Kennedy arrived, a decline has set in, part due to the mechanization of the mines, and Kennedy was seeing its effects.

As he traveled around the state, he learned about the hardships people were facing there and how they were living. As one reporter noted: “He saw wives line up for surplus government food. He heard about kids who saved their school milk for younger siblings at home. He passed abandoned miners’ houses with boards over the windows…” Additional accounts noted his remarks as he made campaign stops throughout the state:

Kennedy talking with children as he campaigned in West Virginia for the state's May 1960 primary.

Clarksburg, April 18, 1960:

“…We talk about new industries and new products for the future – and we must. But we must also do something right now, before those new industries and jobs are here, about those who are unemployed now, who can’t find a job and who can’t get by on an average unemployment check of $23 a week…There are more than 60,000 of those men in West Virginia today and only half of them are drawing unemployment compensation. It is a double failure of our civilization if we cannot permit them to pay their bills and feed their families while looking for another job.”

Bethany College, April 19, 1960:

“…Today the United States is living better than ever before. We have more swimming pools, freezers, boats and air-conditioners than the world has ever seen. ‘But the test of our progress,’ said Franklin Roosevelt, ‘is not whether we add more to the abundance of those who have much; it is whether we provide enough for those who have too little.’ By that test, the last several years have been years of economic failure.”

Glenwood, April 26 1960:

“…Thousands of your citizens — 14,000 here in Mercer County alone — are forced to struggle for subsistence on a diet which consists primarily of flour, rice and cornmeal. A diet which does not permit a healthy, decent existence, a diet which is causing malnutrition, chronic diseases and physical handicaps, a diet which is a disgrace to a country which has the most abundant and richest food supply in the history of the world.”

April 28, 1960. JFK campaigner, 'Bunny' Solomon (North-eastern University, MA, top center) with coal miners in Tioga, WW, displaying "Kennedy For President” bumper sticker.

Author Teddy White would later observe about JFK’s discovery of hunger in West Virginia when writing on the 1960 election campaign in his classic book, The Making of a President:

“…[Senator Hubert] Humphrey, who had known hunger in boyhood, was the natural workingman’s candidate – but Kennedy’s shock at the suffering he saw in West Virginia was so fresh that it communicated itself with the emotion of original discovery. Kennedy, from boyhood to manhood, had never known huger. Now, arriving in West Virginia from a brief rest in the sun and the luxury of Montego Bay, he could scarcely believe that human beings were forced to eat and live on these cans of dry relief rations, which he fingered like artifacts from another civilization. ‘Imagine,’ he said to one of the assistants one night, ‘just imagine kids who never drink milk.’ Of all the emotional experiences of his pre-Convention campaign, Kennedy’s exposure to the misery of the mining fields probably changed him most as a man (emphasis added); and as he gave tongue to his indignation, one could sense him winning friends.”

Campaigning in Amherst, West Virginia, Kennedy addresses miners from atop a station wagon, April 1960. photo Hank Walker

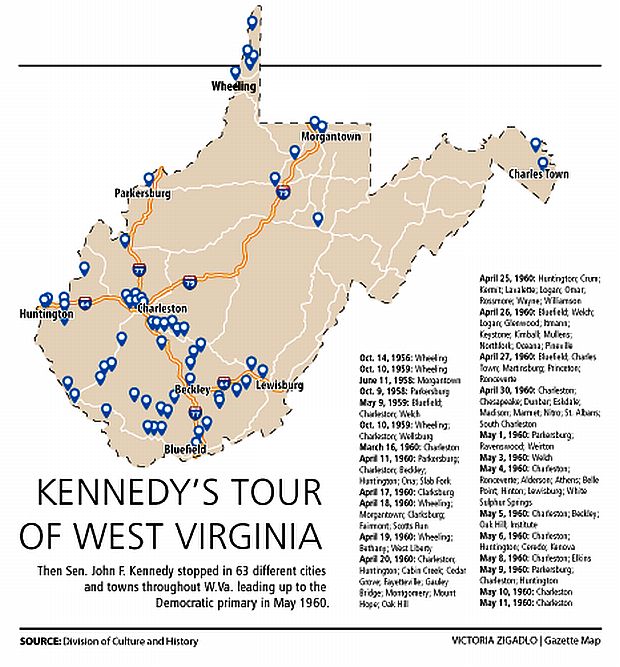

In April and early May 1960, Kennedy made more than 20 campaign trips to West Virginia, according to the state’s Division of Culture and History. During those visits, he made 96 campaign stops at 63 different cities and towns. He told his listeners as he campaigned that the outcome of the West Virginia primary would determine whether he would have a chance at the Democratic nomination. “Help me,” he said during his speeches, “and I will help you,” he promised, should he be elected president.

Map compiled by The Gazette newspaper of Charleston, WV, based on information from the West Virginia Division of Culture & History, showing JFK campaign stops, some dating to 1956, but most prior to the May 1960 primary.

Kennedy defeated Hubert Humphrey in the West Virginia primary with more than 60 percent of the vote, helping dispel doubts that he could win in Protestant territory and that Americans would support a Roman Catholic nominee. He then secured the Democratic presidential nomination at the party’s convention that July in Los Angeles, followed by his November 1960 victory over Vice President Richard M. Nixon to become President of the United States.

JFK signing autographs for workers at the Amherst Coal Company Grill in West Virginia during 1960 campaign stop.

After he was elected president, on January 21, 1961, his second day in office, Kennedy issued his first executive order: a pilot food-stamp program to increase the amount of food distributed to needy people in economically distressed areas. And the first food stamps in this program were issued in McDowell County.

In May 1961, about a year after he had campaigned there, now President Kennedy sent his Secretary of Agriculture to Welch, WV to deliver the nation’s first food stamps — $95 worth — to Alderson Muncy, an unemployed mineworker with 13 children. Three years later, McDowell County would become one of the principal counties in President Lyndon Johnson’s federal War on Poverty legislative effort.

JFK returned to West Virginia in June 1963 for the state’s centennial commemoration. Speaking on the steps of the state capitol in Charleston, he acknowledged that he “would not be where I am now… had it not been for the people of West Virginia.” Five months later, President John F. Kennedy was felled by an assassin’s bullet in Dallas, Texas. To this day, however, photos of JFK can be found hung on the walls of West Virginia homes, alongside those of Jesus Christ, FDR, union leader John L. Lewis, or some such mixture of honored souls.

1968

RFK & Kentucky

After President Kennedy’s assassination in 1963, his successor, President Lyndon Johnson, enacted the federal “War on Poverty,” inspired in part by the poverty found in Appalachia. Johnson’s programs were aimed at alleviating those conditions throughout the region. In February 1968, Robert Kennedy, then on the cusp of jumping into the race for president, toured a string of towns in the coal regions of southeastern Kentucky. He went there to see for himself how this part of Appalachia was faring. His two-day “poverty tour” in February 1968 covered some 200 miles and included stops at a number of towns, among them: Neon, Grassy Creek, Mousie, Fisty, Jackhorn, Cody, and others.

February 1968: Robert F. Kennedy, center, looking down, no top coat, with following crowd of onlookers, staff and media, as he makes his tour of Eastern Kentucky, here on Liberty St., Hazard, KY, photo, Paul Gordon.

RFK, who had served as JFK’s Attorney General, was now a U.S. Senator from New York. And on this trip, he would make scheduled and unscheduled visits with the residents of Eastern Kentucky, including walking tours of small communities, roadside visits with individual families, stops at one-room schoolhouses, speeches at courthouses and colleges, and a look at one strip mine site. As a member of Senate’s Labor and Public Welfare Committee’s Subcommittee on Employment, Manpower and Poverty, Kennedy would also hold two field hearings soliciting the views of area residents. A one-room schoolhouse in Vortex hosted one of Kennedy’s hearings, and the other was held in a school gymnasium at Fleming-Neon.

Robert F. Kennedy greeting residents of Eastern Kentucky as he made his way across the region on his two-day tour.

In the town of Barwick in Breathitt County, Kennedy visited a one-room schoolhouse that was in session. He spoke with each student individually, asking them what they’d had to eat that day.

Reportedly, the teacher there, Bonnie Jean Carroll, always made sure the kids had a big meal at school to be sufficiently nourished. She would send the boys to walk two miles into town to get milk and other things, while the girls cooked. According to some local history assembled at the RFKinEKY.org website, “Bonnie and her students did a lot of cooking in the classroom; they made a big, hot meal every day.”

February 1968: Robert F. Kennedy in Neon, Kentucky where he listened to local residents tell of hardships.

Public Hearing

RFK and party traveled from Whitesburg to the gym in Fleming-Neon where they conducted a three-and-a-half hour hearing. Twenty eastern Kentuckians gave testimony, including: nationally known author and Kentucky native, Harry Caudill, Judge Wooton of Leslie County, LKLP director Stafford, coal miner Cliston Johnson, and David Zegeer of Beth-Elkhorn Coal Company.

Evarts High School student Tommy Duff testified about school conditions, while other students protested, some with paper bags over their heads. They were opposing, the proposed flooding of Kingdom Come Creek by the Beth-Elkhorn Coal Company, which would have displaced their community (In 1956, Consolidation Coal Company, which had been the dominant company in the area for decades, sold its coal interests to Bethlehem Steel, and their mining subsidiary was Beth-Elkhorn). During the hearing, Senator Kennedy also debated with David A. Zegeer of the Beth-Elkhorn asking whether Mr. Zegeer’s company had many stockholders from Kentucky. During the exchange with Zegeer, Kennedy asserted: “Outsiders have come in and exploited the great wealth of the area—with great profits going elsewhere in the country.”

February 15, 1968. Front-page story from ‘The Courier Journal’ newspaper of Louisville, KY, covers RFK’s field hearing at Neon, KY with the headline “Kennedy Condemns Coal Interests For Exploiting Eastern Kentucky”.

Time magazine reported on RFK’s Kentucky visit, noting that he came with “a caravan of 36 cars crammed with out-of-state reporters, committee staffers and electronic gear.” At one stop, Time reported Kennedy being asked: “Why was a man reared to a multi-millionaire’s comforts concerned with the plight of Kentucky’s poor?” Some thought it a simple political calculation, a way to bring the spotlight on himself as a possible contender in that year’s presidential race. Yet others had noted a change in RFK with the assassination of his brother, and that he was looking at social issues in a new way.

Robert F. Kennedy, listening to a miner relay his concerns during a two-day tour in Neon, KY, February 1968. |

Bill Grieder, who covered Kennedy’s Kentucky trip for the Louisville Courier-Journal, noted in a later email recalling the trip: “…Reporters more sophisticated (and cynical) than I assured me he was merely prepping for his as yet unannounced presidential candidacy. Probably so, but you couldn’t imagine any politician slogging through all those hollows and decayed coal camps without some kind of deep conviction.”

Some of those who covered Kennedy on that trip, however, had a different reaction to him. Tom Bethell for one, reporting for The Mountain Eagle newspaper of Whitesburg, KY, had the opportunity to see him in a more private setting, and would later write:

“…[U]p close, Kennedy was harder to read….[I] was struck by how uncurious, even detached, Kennedy seemed when he wasn’t in a public setting. …I found myself riding with him in his car, en route to his next photo-op, and was shocked when a VISTA volunteer in the car tried to engage him in a conversation about what she had learned on the job, and he cut her off, rudely and brusquely. At that moment I thought he was every bit as arrogant as I’d sometimes heard he was, a stereotypically spoiled and entitled little rich kid if ever there was one, and I couldn’t imagine voting for Bobby Kennedy unless the only alternative was Richard Nixon.”

Bethell added, however, that his first impression “might have been completely wrong,” and that Kennedy “might have been a wonderful president, the first since Franklin Roosevelt to offer real and lasting hope for hard-pressed people, rural and urban alike. Or not….”

Back on the 1968 poverty tour, meanwhile, Time magazine quoted Cliston Johnson, 48, a partially disabled miner struggling to raise 15 children on $60 a month: “Whenever you get another kid to feed, just add a little more water to the gravy.” The government’s “gravy,” however – at the time, totaling some $450 million Federal aid to Appalachia since 1965 – had done little to help. Nor were private-sector companies setting up factories in that part of Appalachia, some dissuaded by the ravaged landscape. Kennedy, as Time reported, did not seem inclined toward more federal handouts, quoting him as saying: “Welfare’s not the answer. It’s jobs. It is a basic responsibility of our society to give every man an opportunity to work.” At the tiny school building in Vortex, Kennedy pulled in an overlfow crowd, where he asked questions about diet, clothing and schooling. Over and over again, he said: “This is not satisfactory, this is not acceptable.” And when he said, “We’ve got to do away with welfare,” the people applauded.

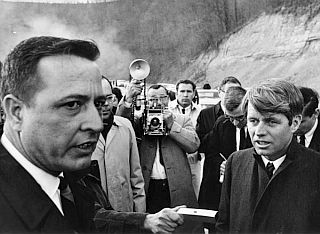

Senator Robert F. Kennedy talking with strip mine owner Bill Sturgill at the Yellow Creek mine site in Knott County, Kentucky, February 1968. |

Strip Mine Site

After leaving Hazard, Kentucky, Kennedy and entourage stopped, unannounced, at the Yellow Creek strip mining site Knott County. In trying to gain access to the site, Kennedy’s entourage was blocked by cars of the mine crew several times. After a contentious moment of negotiation between RFK and the mine’s security staff, mine owner Bill Sturgill allowed Kennedy and his group to access the site.

At the final stop of the Eastern Kentucky tour, in a filmed interview with an off-screen reporter on the streets of Prestonberg (see YouTube video), Kennedy was asked, “Is there anything significant that you’ve learned on this trip?” He answered as follows:

“…Well, people are still having a very, very difficult time… There’s hunger; considerable hunger in this part of the country. There’s no real hope for the future amongst many of these people… who have worked hard in the coal mines. And now the coal mines shut down, they have no place to go. There’s no hope for the future. There’s no industry moving in. The men are trained in government [job training] programs and there’s no jobs at the end of the training program because of the cutback – because of the demands on our federal budget in Washington and the war in Vietnam – even these training programs are being cutback. So people are being cut off, and they have no place to turn. And so they’re desperate and filled with despair. Seems to me that this country, as wealthy as we are, that this is an intolerable condition. It reflects on all of us. We can do things all over the rest of the world, but I think we should do something for our people here in our own country.”

RFK did not have the opportunity to do much of substance for Appalachia following his visit, since shortly thereafter he began his bid for the 1968 Democratic Presidential nomination. And tragically, like JFK, Bobby Kennedy was also taken by an assassin’s bullet. Kennedy was murdered June 5th, 1968, on the night of the California primary, shortly after he won that primary and had made his victory speech. It was four months after his visit to Eastern Kentucky.

In February 1972, New York Times reporter, George Vecsey, doing a four-year follow-up story on RFK’s Kentucky visit, noted: “…The issues have not changed much in four years. Poverty is everywhere; coal miners still die, and the hills are being torn apart ever faster by the strip miners.”

|

Caroline’s Coal Project During the summer of 1973, Caroline Kennedy, daughter of John F. and Jacqueline Kennedy, then 15½ years old, undertook a brief school project in the coal region of Eastern Tennessee’s Campbell County. At home in Massachusetts, while attending Concord Academy, Caroline had developed an interest in film and photography, and that summer she would work on a documentary film about earlier coal mining and coal camps in Tennessee. During this project, she stayed at the home of former Catholic nun and community advocate, Marie Cirillo, in the Rose’s Creek area near Eagen, Tennessee. Caroline came to Tennessee with a high school friend, Allyson Riclitis, who were among eight students helping to make a film history of the area.  July 1973: Caroline Kennedy, left, poses with local resident Pauline Huddleston at Huddleston's home in Eagan, Tennessee.  July 1973. Caroline’s friend, Allyson Riclitis, about to sample some local moonshine as Marie Cirillo looks on. Photo, C. Kennedy. By 1973, Cirillo, among other projects, had obtained a grant for an oral history project on earlier coal mining in the region and “coal camp” towns that had formerly existed there. The Clearfork area of Tennessee was then made up of twelve unincorporated communities located between the towns of Jellico, Tennessee, and Middlesboro, Kentucky. As Cirillo would later explain: “When I arrived there, the company towns had been dismantled, mainly because of the shift from deep mining to strip mining as new technology made that possible. Big machines now dug the coal. Production no longer required people, so the companies tore down the miners’ homes because they no longer had to provide housing. That was when people realized for the first time that over the years the companies had bought up most of the land.”  Rough copy of July 1973 AP wire story: 'Caroline Kennedy Joins Crew Taping History of Coal Camps'.  Marie Cirillo some years later, undated photo.  Caroline Kennedy profiled by Parade magazine in Sept 2011 at release of her book, “Jacqueline Kennedy: Historic Conversations on Life with John F. Kennedy.” Kennedy, a graduate of Harvard and Columbia Law school, went on to publish several books, and became involved in the JFK Presidential Library and the Profile of Courage Awards. She also served as America’s ambassador to Japan during the Obama Administration. |

U.S. Senator Edward Kennedy, Feb. 2004.

Ted Kennedy

Edward Moore “Ted” Kennedy served as a U.S. Senator from 1962 until his death in 2009. His service of 46 years in the U.S. Senate at that time made him the fourth-longest, continuously-serving senator in U.S. history. In those years, Kennedy became a friend of labor, and held forth on Senate committees helping to craft and watch over occupational health and safety matters. Kennedy was one of the Senate leaders who helped pass the Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970, which created OSHA, the federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Prior to passage of the act, there were few federal health and safety protections for workers. And in later years, as well, Kennedy would help to defeat attempts to weaken the law.

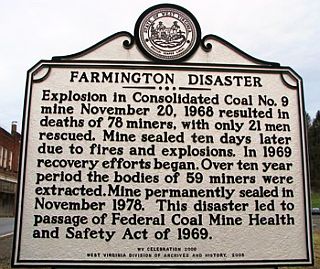

Coal mine safety was also one of the areas Kennedy would become involved with as he sought improved worker health and safety regulation. For decades, coal-mine disasters had killed miners regularly. Some mine explosions and fires would kill dozens and even hundreds of miners at a time. The Coal Mine Health and Safety Act of 1969, generally known as “the Coal Act,” was the first meaningful law to help govern mining practices. It came about following the deaths of 78 miners at the November 1968 Farmington Mine Disaster in West Virginia.

West Virginia historic marker for the Farmington mine disaster, which killed 78 miners, and helped spur Congress to pass the Federal Coal Mine Health & Safety Act of 1969.

Indeed, a few years later more coal-related disasters would ensue. In February 1972, at Buffalo Creek, West Virginia, 125 persons died when a coal waste dam burst sending a near tidal wave of coal waste water through a seventeen mile-long valley, leaving a trail of devastation as it went. In July 1972, at Blacksville, West Virginia, a fire was sparked by a continuous mining machine that came into contact with an electric wire, igniting the coal seam. Nine miners who had not been adequately trained in emergency procedures, became trapped and died in the mine.

Senator Kennedy in his younger years, shown here at a 1979 Judiciary Committee hearing.

New Law. These incidents and others stirred Washington to action again, as House and Senate committees investigated and held hearings. On February 11, 1977, S.717, the Federal Mine Safety and Health Amendments Act, was introduced by Sen. Harrison Williams (D-NJ), with Senator Kennedy and 25 others as cosponsors. The Harrison bill revised the 1969 Coal Act with the Mine Safety and Health Act of 1977, also known as “the Mine Act.” It was signed by President Carter in November 1977. This law consolidated federal health and safety regulations for coal and non-coal mining; moved the new Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA) to the Department of Labor; strengthened and expanded the rights of miners; and enhanced their protection from retaliation. Mining fatalities would drop sharply in subsequent years, but problems still remained.

The Reagan Years. In the 1980s, as the Reagan Administration and the mining industry sought to weaken mine safety regulations, Senator Kennedy and his staff geared up for battle, focusing a series of hearings on the lax regulatory oversight by Reagan’s MSHA. Kennedy described the record of that agency as “shameful and tragic,” and kept pressure on MSHA to strengthen its programs and enforcement. Among those who testified before Kennedy at a March 1987 hearing was J. Davitt McAteer, a lawyer and coal miner’s son who then headed the Occupational Safety and Health Law Center, a public interest group in Washington, D.C.“We know how to prevent many of the unnecessary deaths in the mines. What we seem to have lost is the will to do what good judg-ment and the law require.” – Senator Kennedy, 1987 McAteer testified that in a six-year period during the Reagan Administration, MSHA had muzzled many of its inspectors, dissolved its most successful criminal investigative team, and administratively reduced serious safety violations to minor ones. Since the Federal mine safety act’s adoption in 1969, McAteer stated there had been 2,029 fatal accidents in American coal mines, but only 38 attempts to prosecute those involved under criminal provisions of the law. Kennedy, referring to the Federal mine safety act and MSHA’s powers during the hearing, said: ”We know how to prevent many of the unnecessary deaths in the mines. What we seem to have lost is the will to do what good judgment and the law require. It makes me angry every time I hear about a miner killed because someone would not do his job.” Although no new mine safety legislation was enacted at that time, the Reagan administration did agree to hire about 100 additional mine inspectors, and also rescinded one rule that had reduced criminal convictions of negligent coal operators.

Ted Kennedy, 2005 press conference.

In July 2002, Kennedy, still chairman of the Senate Labor Committee, and the late Sen. Paul Wellstone (D-MN), chairman of its Subcommittee on Employment, Safety and Training, held hearings to investigate coal mine safety, focusing in part on MSHA’s enforcement at the Jim Walters Resources coal mine in Brookwood, Alabama where 13 miners had been killed in a September 2001 explosion. At the time, the mine had 31 outstanding violations, and MSHA inspectors had not returned to determine if they had been corrected. During the hearings, Kennedy called MSHA enforcement record “dismal,” while Wellstone noted that mine fatalities were rising but the Bush Administration had cut MSHA’s 2003 budget by 6 percent. However, as Kennedy and Wellstone tried to turn the spotlight on MSHA’s record, two weeks after their hearing, a few MSHA officials received high media attention and national praise in the successful rescue of 9 coal miners trapped in a flooded underground mine in Somerset County, Pennsylvania. MSHA reforms were then somewhat derailed. Then, several years later, there was another mine tragedy.

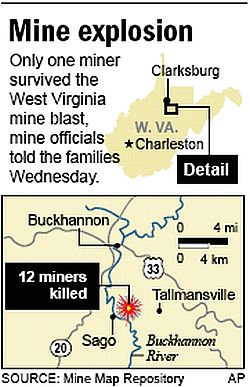

Sago Disaster

Associated Press map & reporting, Jan 2006.

A few days after the Sago Mine had exploded, Kennedy told an Associated Press reporter that Senate hearings were needed to determine how the tragedy happened. “We owe it to these miners and their families to find out what happened and whether this accident could have been prevented,” Kennedy said. “In addition, we should investigate the troubled history of repeated safety violations at the mine.”

Then, just few weeks following the Sago explosion, another West Virginia mine accident occurred this one on the morning of January 19, 2006, at the Aracoma Alma Mine in Logan County. The accident occurred when a conveyor belt in the Aracoma Alma Mine No. 1 at Melville in Logan County, West Virginia, caught fire. The conveyor belt ignited pouring smoke through the gaps in the wall and into the fresh air passageway that the miners were supposed to use for their escape, obscuring their vision and ultimately leading to the death of two of them by carbon monoxide poisoning when they became separated from 10 other members of their crew. The others held onto each other and edged through the air intake amid dense smoke to make their escape. At the time of the fire, the mine was owned by Aracoma Coal Company, a Massey Energy company.

Map showing somewhat larger area and location of the Sago Mine and Alma Mine tragedies of January 2006.

Low Fines

At a hearing held March 2, 2006, by the Senate HELP committee (Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions) to discuss the state of mine safety, Senator Kennedy was present to voice his concern about mine safety enforcement. In an impassioned statement, Kennedy said that fines as low as $60 give companies “little incentive to make safety improvements.” He added that while he understood that MSHA was then proposing to raise the maximum fines from $60,000 to $220,000, “such gestures are meaningless unless MSHA actually issues those fines.”

2006 Associated Press graphic showing dollar amounts of fines that then could be levied per infraction by various federal agencies, with mine safety fines being the lowest, a limitation Senator Kennedy & others found deplorable.

In the year prior to the Sago Mine disaster, the operator reportedly received over 200 safety citations, half of them being serious enough to potentially lead to injuries.

David G. Dye, then acting assistant secretary of MSHA, responding to Kennedy, said that the agency had collected $25 million in fines in 2005 and reductions were the result of actions taken by independent administrative law judges. He also said that the 1977 Mine Act “does not give MSHA the authority to preemptively close entire mines because of the frequency of violations.” Sen. Robert C. Byrd (D-WV), who grew up in a coal-mining community, said during the hearing that MSHA “had the legal authority to require higher fines” but “didn’t use it.”

January 2003. AP file photo of Senators Robert Byrd (D-WV) and Ted Kennedy on Capitol Hill. photo, Susan Walsh.

Byrd, frustrated with the agency said at one point, “It’s been 25 years since mine safety rules have been updated,” Byrd said. “How long do we have to wait?”

Byrd, Kennedy, and others in the U.S. Senate did not wait. In 2006, Congress passed the Mine Improvement and New Emergency Response Act (the MINER Act), which President Bush signed into law June 15 2006. The new law required mine-specific emergency response plans in underground coal mines; installation of wireless communications equipment and tracking devices within three years; new regulations for mine rescue teams and sealing abandoned areas; and prompt notification of mine accidents. The MINER Act also raised maximum fines for accidents and gave the government the power to shut down mines when operators failed to pay fines. Senator Kennedy, meanwhile, continued to push for additional mine safety reforms, as yet another mine disaster occurred not long after the MINER Act passed.

Map showing location of Crandall Canyon Mine.

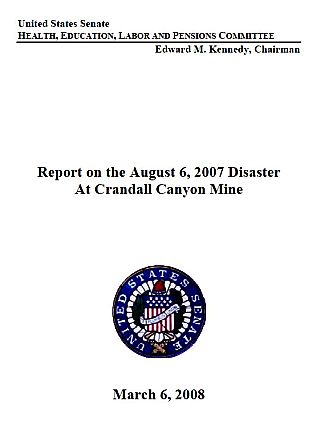

In August 2007, the Crandall Canyon Mine, an underground coal mine in Utah’s Wasatch plateau near Huntington, made headlines when six miners were trapped by a mine collapse. Ten days later, three rescue workers were killed and six more injured as one of the walls of the tunnel exploded inward, toward the rescuers, as they attempted to reach the trapped miners.

On August 31, 2007 the search for the six trapped miners was called off and declared too dangerous for continued rescue efforts. The six men originally trapped were later declared dead and their bodies were never recovered. The mine was then operated by Genwal Resources Inc., an operating division of UtahAmerican, a subsidiary of the Murray Energy Corporation.

Senator Ted Kennedy, shown here in another Senate proceeding, had his committee staff compile a report on the Crandall Canyon mine collapse in Utah.

“The loss of life at the mine, and the devastating emotional toll on families of the victims, underscore the urgent need for a thorough examination of our federal system of mine safety,” Kennedy said in his letter to Chao. In particular, Kennedy said he was “troubled” by reports that roof problems were not reported to MSHA, and that the roof had reportedly collapsed in other areas of the mine where workers were using a dangerous technique called “retreat mining.” Such reports, Kennedy said in his letter to Chao, “raise questions about the integrity of the mine operator’s reporting and the rigor of MSHA inspections.”

Cover of Senator Kennedy’s Committee report on the August 2007 disaster at Utah’s Crandall Canyon coal mine.

“The committee’s investigation has revealed that the owner of Crandall Canyon Mine, Murray Energy, disregarded dangerous conditions at the mine, failed to tell federal regulators about these dangers, conducted unauthorized mining and, as a result, exposed its miners to serious risks,” Kennedy said. The report also charged that the operator’s parent company, Ohio-based Murray Energy Corp., bullied MSHA to gain approval of its overall mining plan.

“MSHA also unconscionably failed to protect miners by hastily rubber-stamping the plan,” said Kennedy. “This is a clear case of callous disregard for the law and for safety standards, and hard-working miners lost their lives. This deserves a full criminal investigation by the Department of Justice.”

Kennedy’s report was followed by a report from the Labor Department’s Inspector General which found that MSHA failed to protect workers at the Crandall Canyon mine. That report blamed federal mining regulators for negligence in approving a roof-control plan for the mine. An audit of events preceding the two collapses found that lower-level MSHA officials skipped many of the agency’s own protocols in approving a roof control plan for the Crandall Canyon mine and could have been subject to “undue influence” by the mine’s operator. It also found that MSHA could not show it made the right decision when it approved risky retreat mining at Crandall Canyon and found the agency “negligent” in its duty to protect underground miners in the Crandall Canyon mine disaster, and in mines across the nation. Rep. George Miller’s (D-CA) House Education and Labor Committee also released a May 8, 2008 report on the Crandall Canyon disaster that repeated the call for a criminal investigation.

On July 24, 2008 MSHA issued one of its highest fines then to date for coal mine safety violations at the Crandall Canyon Mine. Genwal Resources was fined $1.34 million “for violations that directly contributed to the deaths of six miners last year,” plus nearly $300,000 for other violations. MSHA also levied a $220,000 fine against a mining consultant, Agapito Associates, “for faulty analysis of the mine’s design.”

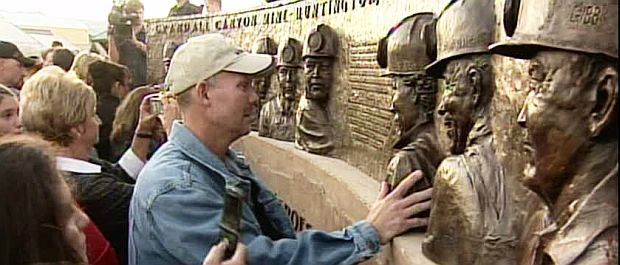

September 2008: Dedication of the memorial commemorating the lives of the 6 miners and 3 rescuers killed at the Crandall Canyon Mine in Huntington, Utah. The memorial is titled, 'Heroes Among Us', sculpture by Karen Jobe Templeton.

Coal mine health and safety to this day continues to be a vexing issue, with mine disasters such as the April 2010 coal mine explosion at the Upper Big Branch Mine in Raleigh County West Virginia that killed 29 coal miners, while black lung disease continues to diminish coal miner health and take their lives. Yet in recent decades, the efforts of public servants like Ted Kennedy and others have helped make coal mining and other workplaces safer than they might otherwise have been – although, to be sure, they are not as safe as they should be. In 2008, Senator Ted Kennedy was named one of the 50 most influential EHS leaders by Occupational Hazards magazine (now EHS Today) for his 40-plus years of advocating for workers’ rights and health and safety in the U.S. Senate. After a battle with a malignant brain tumor, diagnosed in May 2008, Ted Kennedy passed away in late August 2009.

December 2009: RFK, Jr. at Charleston, WV rally speaking out against mountaintop mining at the Coal River Mountain site.

RFK, Jr.

Of all the Kennedys who have worked on coal-related issues over the years, few have been more active than Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., son of Robert and Ethel Kennedy. A graduate of Harvard College (1976) with a law degree from the University of Virginia, plus a Masters of Law from Pace University, RFK, Jr. has worked on a wide range of environmental issues, both as a litigating attorney and environmental activist.

He began his environmental work in the 1980s when he joined New York’s Hudson River Keeper, later doing battle with the likes of General Electric and Con Edison in New York over pollution and land development issues. He also joined the staff of the Natural Resources Defense Council in the 1980s, and would become a senior attorney there through the early 2000s.

Kennedy is co-author of the 1997 book, The Riverkeepers, with John Cronin and helped spread the “waterkeeper model” of protecting rivers, bays and estuaries throughout the U.S. and around the world. In 1999, Kennedy and others formed the Waterkeeper Alliance which unites more than 200 Waterkeeper organizations in common action. The work of protecting rivers, harbors and estuaries brought Kennedy and his allies into direct contact with the coal cycle, whether strip mine blasting and mountaintop removal, power plant CO-2 and mercury emissions, or coal ash dumps polluting rivers and lakes throughout America.

In recent years, Kennedy has been in the thick of the nation’s battle to end the excesses of coal mining and coal pollution. He has made numerous appearances at activist and citizen rallies, lent his name to many local fights, written Op-Eds, and helped make and promote a documentary film on mountaintop removal. Like his father and uncle before him, RFK, Jr has pushed economic and policy strategies to help alleviate the hardships on coal communities. But unlike them, he has also worked as an activist and litigator, often taking a more aggressive approach with the coal and utility industries.

In February 2009, the Waterkeeper Alliance launched its “Clean Coal is a Deadly Lie” campaign, which rose in part as a response to a $49 million advertising push by the coal and utility- backed American Coalition for Clean Coal. The Waterkeeper campaign – often in league with other national environmental and local citizen groups – would later include dozens of lawsuits targeting strip mining practices, mountaintop removal, slurry pond construction, mercury emissions, coal ash piles, and coal export terminal expansion in the Pacific Northwest.

Example of mountaintop removal strip mining in progress at Kayford Mountain, West Virginia when this photograph was taken.

In a March 25, 2009 Washington Post Op-Ed by Kennedy titled, “Stopping Mountaintop Removal Coal Mining,” he wrote:

…Having flown over the coalfields of Appalachia and walked her ridges, valleys and hollows, I know that this land cannot withstand more abuse. Mountaintop-removal coal mining is the greatest environmental tragedy ever to befall our nation. This radical form of strip mining has already flattened the tops of 500 mountains, buried 2,000 miles of streams, devastated our country’s oldest and most diverse temperate forests, and blighted landscapes famous for their history and beauty. Using giant earthmovers and millions of tons of explosives, coal moguls have eviscerated communities, destroyed homes, and uprooted and sickened families with coal and rock dust, and with blasting, flooding and poisoned water…

November 2003. Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., National Press Club luncheon speaker, in critique of the Bush Administration’s environmental policies.

In an April 2009 interview with ABC News, Kennedy let fly on how the coal industry was in effect ruining the environmental commons and preventing the public from using certain resources because it has polluted them:

…You know, we’re living today, truthfully, in a science fiction nightmare. Our country, where my children and the children of most Americans can no longer engage in the seminal primal activity of American youth, which is to go fishing with their father in the local fishing hole and then come home and safely eat the fish. Because somebody gave money to a politician and poisoned more than half of the fish in this country with mercury. And it’s the coal industry, and they are privatizing a public trust resource, the fish of our country, which belong to us, they belong to the people. But now the coal industry owns them and the utilities. Because they poison them so much we can’t use them anymore….

Publicity poster for the “RFK, Jr./ Don Blankenship” debate held in January 2010 at the University of Charleston.

Coal Debate

In late January 2010, Kennedy debated the notorious West Virginia coal baron, Don Blankenship, then head of Massey Energy, over mountaintop removal, climate change, and coal’s future. The debate was held at University of Charleston and moderated by university president, Ed Welch. It was also broadcast online and on television stations across West Virginia. With advance billing, the Kennedy-Blankenship duel received considerable interest, especially in West Virginia and among some national media.

Blankenship, an outspoken climate change denier and environmental critic, told a packed house that night: “The mission statement for coal is prosperity for this country. This industry is what made this country great and if we forget that, we’re going to have to learn to speak Chinese.” Kennedy countered that giant mining machines have cost thousands of jobs while mountaintop removal was destroying ancient peaks and burying pristine streams. “This is the worst environmental crime that has ever happened in our history,” Kennedy said. “These companies are liquidating this state for cash with these gigantic machines.”

Don Blankenship, RFK, Jr., and moderator, Ed Welsh, president of the University of Charleston during debate.

…When Kennedy accused [Blankenship] of leaving behind ghost towns across WV, Blankenship responded that he’d bought up all those homes at fair market value (“those people left voluntarily”). In response to Kennedy’s points on water pollution, Blankenship effectively dismissed the threat of mercury as a bunch of hype on the internet. …When Kennedy listed the social and health damages done by coal — “externalities” the industry charges to taxpayers — Blankenship mumbled, “do we have some of those externalities? I don’t know. Maybe.” When Kennedy pointed out that China is dumping trillions into renewable energy, Massey responded that they were only building windmills to appease the UN. When Kennedy pointed out that Massey’s own disclosure revealed some 12,000 violations of the Clean Water Act last year, Blankenship responded that they’re reducing their violations year to year, now that they’ve been reminded by the EPA that it would be a good idea.

…He simply dismissed Kennedy’s facts and stuck to his narrative: global warming’s a hoax, hippie environmentalists are strangling free enterprise, out-of-staters have no right to question what happens in WV, and China is going to take over if we don’t mine and burn all the coal we can as fast as we can. We’re crazy to be worried about “parts per million” of pollutants when coal is the only thing keeping our life expectancy above Angola’s….

A few months later, in March 2010, Kennedy and Blankenship followed-up with more of their arguments in dueling Op-Eds in The Hill newspaper that circulates on Capitol Hill and in the Washington, DC community. (A few months after Blankenship and Kennedy had debated, in April 2010, on Blankenship’s watch as CEO, the mining catastrophe at Massey’s Upper Big Branch Mine in West Virginia occurred in which 29 miners were killed. Facing multiple charges in connection with that incident, and much legal wrangling over the next few years, Blankenship in the end, was found guilty of one misdemeanor charge of conspiring to willfully violate mine safety and health standards for which he served one year in jail and was fined $250,000. In 2017, having served his time, Blankenship then filed papers to run for the U.S. Senate).

June 2011, Blair Mountain, West Virginia. RFK, Jr. tells crowd that Big Coal, while forever promising prosperity, had instead left a legacy of devastation and poverty for coal communities.

Blair Mountain

For five days in June 2011, nearly 800 citizen activists marched 50 miles through West Virginia from the town of Marmet to the town of Blair to protest mountaintop strip mine on Blair Mountain. Adding to the protest at this location was the commemoration of the 90th anniversary of the Battle at Blair Mountain, a 1921 bloody fight by coal miners to unionize their mine. (For five days some 10,000 armed coal miners battled 3,000 lawmen and Pinkerton strikebreakers backed by coal mine operators, only ending after the intervention of the U.S. Army by presidential order). The battle site, having been accepted for National Historic Site designation in 2009, was delisted in 2010 after objection from the state of West Virginia and the coal industry. An estimated crowd of 2,000 citizen activists, union workers, historians, environmentalists gathered for the June 2011 rally at the site seeking to end mountaintop removal and restore the historic site designation, among other issues. Joining the speakers that day was Robert Kennedy, Jr., who told the crowd that Big Coal, while forever promising prosperity to West Virginia, had left a legacy of devastation and poverty. As of October 2017, the historic site designation was still under consideration. A relisting of Blair Mountain Battlefield site on the Historic Register would cease surface mining operations on the mountain.

Coal River Film

In June 2011, a documentary film on Appalachian coal mining was released, The Last Mountain, co-written by Bill Haney and Peter Rhodes and produced by Haney, Clara Bingham and Eric Grunebaum. The film focuses on the mountaintop mining fight then occurring over Coal River Mountain in West Virginia. In the film, RFK, Jr. is featured joining local activists trying to stop Massey Energy Co. (acquired by Alpha Resources in 2011) from destroying Coal River Mountain. Massey/Alpha then held many of the necessary permits to begin stripping the mountain and fill nearby valleys in the process. Instead, Kennedy and opponents advocate using the Coal River Mountain site for wind generation; a site found to hold high wind potential – high enough, in fact, with wind farm development, to produce 328 megawatts of electricity, which could power 70,000 homes. That option is presented in the film as a better alternative for the environment and nearby communities, while also producing more jobs as well.In the film, several local activists are introduced along with stories to present some of the problems associated with strip mining and coal development in the Coal River Valley area. Maria Gunnoe describes how the hills surrounding her home in the town of Bob White had been stripped of forest cover and topsoil, resulting in down-mountain flash flooding, imperiling communities below. Ed Wiley, a former mountaintop coal miner, worried about his granddaughter’s school, Marsh Fork Elementary, located a short distance below an earthen dam holding back a slurry pond with 1.8 billion gallons of coal waste. And Jennifer Hall-Massey from the town of Prenter, explains that six of her immediate neighbors have died of brain tumors, and the only thing they had in common was the well water. She and 264 of her neighbors would sue local coal companies and West Virginia arguing that the companies pumped millions of gallons of coal slurry waste into the ground surrounding Prenter, polluting their well water with heavy metals like arsenic and lead, and causing disease.

The 95 minute film premiered at the 2011 Sundance Film Festival and then went into general release in June of that year. Kennedy and Haney also did media interviews to help promote the film.

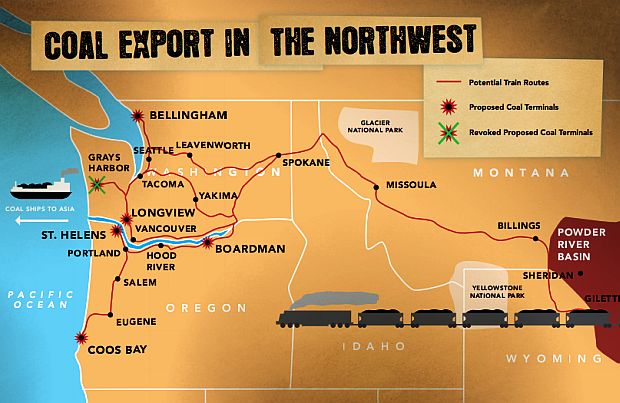

Coal Exports

As noted at the top of this story, RFK, Jr. also became involved in the coal export issue. In May 2012 he spoke at a Portland, Oregon rally of citizen activists opposing coal export expansion in the Pacific Northwest. At the time, coal companies were targeting the Pacific Northwest with six separate coal export terminals, which would send stunning volumes of U.S. coal from the Powder River Basin through the Pacific Northwest to Asia. One proposal would send a dozen coal trains each day through Portland, Oregon neighborhoods. The Columbia River Gorge would face up to 30 coal trains per day.

Coal Export overview in the Northwest U.S. as of 2013 or so, showing proposed coal export terminals & possible train routes from the surface coal mines in the Montana / Wyoming Powder River Basin. Not all of the proposed Washington and Oregon coal export terminals on this map are still proposed. Map by Think Progress.

At the May 2012 Portland, Oregon rally, Kennedy said: “Oregon and Washington leaders are faced with a choice between healthy communities with a clean energy future or becoming tied to trafficking coal, the most toxic fuel on earth… “ Kennedy argued that the proposals to bring coal to Oregon and Washington state would lead to political corruption and environmental damage, while the actual number of jobs created would be minimal. And while some may believe the U.S. can simply “export away” the environmental problems associated with coal, Kennedy warned that mercury and other coal pollutants from coal combustion in Asia will still come back to America’s Pacific shores.

Coal Ash

Coal ash, generated by hundreds of coal-fired power plants in the U.S., is one of the nation’s single largest waste streams. Fly ash, a byproduct of burning coal is generated at power plants, as are other coal-burning related wastes, such as bottom ash, boiler slag, and sludges from flue gas desulfurization. Coal ash waste, in one form or another, is found in all regions of the country. The amount generated annually is staggering – currently exceeding 140 million tons a year. A portion of the nation’s coal ash is recycled in construction and other materials. But the lion’s share, for many years, had been dumped or “stored” in coal ash waste lagoons and landfills which have been poorly regulated. There are more than 1,100 known coal ash impoundments and nearly 400 known coal ash landfills in the U.S., many of which do not have liners and/or pollutant collection systems. Coal ash wastes contain harmful pollutants, including arsenic, cadmium, lead, selenium, and other toxic metals that can damage the environment, kill aquatic organisms and cause cancer and neurological harm in humans.

December 2008. The failure of a giant 84-acre coal ash impoundment (upper right) at TVA’s Kingston Fossil Plant in Tennessee, released 5.4 million cubic yards of coal ash slurry into the Emory and Clinch rivers and the downstream community of Harriman, TN.

Coal ash received national attention in December 2008 with the failure of a giant 84-acre coal ash impoundment at the Tennessee Valley Authority’s Kingston Fossil Plant in eastern Tennessee, which released 5.4 million cubic yards of coal ash slurry into the Emory and Clinch rivers. The downstream community of Harriman, TN was hit with a gigantic toxic mess, with sludge deposits as thick as six feet. Three years later they were still cleaning up. Less catastrophic, however, and perhaps even more serious, is the out-of-sight leakage and ongoing discharges from hundreds of coal ash impoundments all across the country.In July 2013, RFK, Jr. was among those trying to bring more public attention to this issue.

In North Carolina, Kennedy appeared at a press event with a group of environmental leaders and activists highlighting toxic discharges into local waterways from a Duke Energy coal ash pond at the company’s former Riverbend powerplant location near Charlotte, North Carolina. The discharges there were making their way into Mountain Island Lake, a drinking water source for more than 800,000 people in Charlotte and other communities. During the event, which also included release of report on the failures of coal ash regulation and extent of the problem nationwide and in North Carolina, Kennedy joined project leaders from Sierra Club, the Environmental Integrity Project, and the Catawba Riverkeeper showing local media where illegal discharges from the Duke Energy coal ash pond were occurring.

Coal Ash Pollution, July 2013: RFK, Jr. joins Sierra Club's Mary Anne Hitt (left); Catawba Riverkeeper, Sam Perkins (black shirt); and Environmental Integrity Project's Eric Schaeffer (far right) in press event showing reporters illegal discharge locations of toxic heavy metals from Duke Energy’s Riverbend, NC coal ash pond. Photo: Waterkeeper Alliance

“…[T]his is harming people,” Kennedy said during a press conference at the Mountain Island Lake boat ramp. “We know it’s causing illness. Hundreds of thousands of people are being injured by it every year. And yet this industry continues its assault on the American public and the environment…” One section of the report released that day by the groups was titled, “Coal Rivers: Duke Energy’s Toxic Legacy in North Carolina,” covering the impact of the company’s 10 power plants in the state. Some months later, in fact, in February 2014, another closed Duke Energy coal-fired power plant near Eden, North Carolina, spilled tens of thousands of tons of coal ash and 27 million gallons of contaminated water into the Dan River, coating 70 miles of that river with a gray sludge.

Dec. 2014. RFK, Jr., Op-Ed: “Coal, An Outlaw Enterprise,” NYT.

In his writing and speeches, Kennedy often singles out “money in politics” as the chief driver of environmental woes – the fact that corporate polluters are essentially buying the politicians to service their industries and protect them from regulation. So for him, campaign finance reform – getting the big money out of politics – is a top priority, along with electing politicians that will support that goal.

Since 2016, Kennedy and his various Waterkeeper organizations in the U.S., have been following closely the regulatory actions of the Trump Administration, filing lawsuits when necessary to challenge industry and Administration proposals that will weaken or remove key EPA, Clean Water Act, and other regulations. In July 2017, for example, RFK, Jr. “If you believe in markets, you have to believe that the era of coal has ended.”

– Robert F. Kennedy, Jr.testified before an EPA panel in Washington on EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt’s move to overturn an Obama Administration coal ash rule that established new standards for coal ash disposal sites, including inspections and monitoring to prevent leaks and spills.

Meanwhile, in terms of the overall coal economy, Kennedy believes that market forces will win out, with renewable energy sources – especially wind and solar – generating the more favorable economic results. “Anything that Trump does is not going to bring back a single coal job – not one,” Kennedy has said. “If you believe in markets, you have to believe that the era of coal has ended.” As an example, in his speeches, Kennedy has often ticked off the costs of various energy alternatives. “An industrial utility scale solar plant in this country costs $1 billion a gigawatt. A coal plant costs $3-5 billion a gigawatt, an oil plant or gas plant costs $3-5 [billion per gigawatt], and a nuke plant costs $9-15 [billion per gigawatt].” Given these economic realities, he believes renewables will eventually drive out the “incumbents,” i.e., coal, oil, etc.,. Still, the policy battles will continue.

The Fights Ahead

The Kennedy family involvement in the nation’s coal travails for nearly 60 years has not, of course, been the singular force in helping alleviate the hardships and damage found throughout the coalfields during those years. Hundreds of activists, politicians, journalists, union leaders, government officials, and others have also been involved. Still, the nation has been fortunate to have had members of this politically prominent family doing what they could to help rein in the excesses of coal power and push reforms. Indeed, in the continuing battles ahead with coal and the broader fossil fuels industry, political leadership of that kind will be needed on many levels – plus widespread public support – to bring about lasting change.

For additional stories at this website on energy/environment issues see the “Environmental History” topics page. See also the “Kennedy History” page for stories in that category. And if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research and writing at this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

____________________________________

Date Posted: 19 December 2017

Last Update: 4 April 2021

Comments to: jdoyle@pophistorydig.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Coal & The Kennedys: 1960-2010s,”

PopHistoryDig.com, December 19, 2017.

____________________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

John F. Kennedy

Dallas Boothe, “Kennedy Says Primaries Important; Thinks People Should Have Right To Choose Presidential Nominee,” Raleigh Register, April 12, 1960.

“Kennedy Raps Food Program; Says GOP Failed To Make Enough Food Available,” Raleigh Register, April 20, 1960.

“The Kennedy Boys Return to Stump; Robert and Teddy Campaign for John in West Virginia but Women Stay Out,” New York Times, May 1, 1960.

“April 6, 1960 – Senator John F. Kennedy Talking With Coal Miners in Raleigh County, West Virginia,” YouTube.com, posted by HelmerReenberg, January 28, 2009.

David Gutman, “He [JFK] Never Forgot West Virginia,” Gazette-Mail (West Virginia), Thursday, November 21, 2013.

Rick Hampson, “When W.Va. Lost its Voice: JFK’s Death Still Resonates,” USA Today, October 29, 2013.

Bill Archer, “John F. Kennedy Wins the Hearts of Southern West Virginia Coalfield Voters,” Bluefield Daily Telegraph (Bluefield, WV), November 22, 2013.

Phil Kabler, Statehouse Reporter, “Historic 1960 Humphrey-Kennedy Debate Took Place in WV,” Gazette-Mail, Monday, July 27, 2015.

_________________________

Robert F. Kennedy

“Poverty: Misery at Vortex,” Time, February 23, 1968.

“Robert Kennedy in Eastern Kentucky 1968,” YouTube.com, posted March 30, 2010.

George Vecsey, “Vortex, Ky., Recalls Robert Kennedy,” New York Times, February 13, 1972.

“RFK in EKY,” The Robert F. Kennedy Perfor-mance Project, RFKinEKY.org.

“Barwick, KY: An Email From William Greider on RFK’s Visit to Barwick School,” RFKin-EKY.org.

Thomas N. Bethell, “Speak Your Piece: To Watch in 1968, and to Hope in 2007,” DailyYonder.com, July 15, 2007.

Trena KP, “How Did the People of Eastern Kentucky Respond to [Robert F.] Kennedy’s Visit?,” RFKinEKY.Blogspot, December 2, 2010.

Samira Jafari, Associated Press, “Poverty Tour Returns to Kentucky,” USAtoday.com, July 17,2007.

_________________________

Caroline Kennedy

Associated Press (Clairfield, TN), “Kennedy Daughter Helps Make Film,” The Lewiston Daily, Sunday, July 3, 1973.

Hildegarde Hannum, ed., “Marie Cirillo: Stories From an Appalachian Community,” Twentieth Annual E. F. Schumacher Lectures, Salisbury, CT, October 2000.

Associated Press, “Caroline Summer Sweetheart Of Coal Mine Camps,” The Indianapolis Star (Indianapolis, IN), July 8, 1973, p. 3.

Associated Press (Clairfield, TN ), “Caroline Kennedy Joins Crew Taping History Of Coal Camps,” The La Crosse Tribune (La Crosse, Wisconsin), July 10, 1973, p. 8.

“Caroline Kennedy Finds Quiet Among Hill Folk,” The Kansas City Times (Kansas City, MO), July 12, 1973, p. 24.

UPI (Egan,TN), “Caroline Kennedy’s Job Ends,” Washington Post, July 19,1973.

Fred Brown, “Caroline Kennedy Recalls a Summer in Rose’s Creek,” Knoxville News-Sentinel, January 31, 1993.

C. David Heymann, American Legacy: The Story of John and Caroline Kennedy, Atria Books, July 2007.

Mark T. Banker, Appalachians All: East Tennesseans and the Elusive History of an American Region, University of Tennessee Press, April 2010.

Georgiana Vines, “For More than 40 Years, a Former Nun from New York Has Helped Appalachian Communities,” KnoxNews.com, March 27, 2010.

Georgiana Vines, “Marie Cirillo’s Career Serving Appalachia Ending,” Knoxville News Sentinel, August 25, 2013.

Merisa Tomczak, “Community Leader: Marie Cirillo,” Appalachian Student Health Coalition, Archive Project, June 2, 2015.

_________________________

Ted Kennedy

“Congress Clears Comprehensive Coal Mine Safety Bill,” CQ Almanac (Congressional Quarterly, Washington D.C., 1969.

Richard D. Lyons, “Appalachia Poor Hit Health Care; Kennedy Committee Is Told of Delays and Neglect,” New York Times, April 20, 1971.

“S.717, Federal Mine Safety and Health Amendments Act,” Congress.gov, 95th Congress, 1977-1978.

George Lobsenz, UPI, “Kennedy Charges Mine Safety Rules Dangerously Weakened,” UPI.com, March 11, 1987.

Ben A. Franklin, “Mine Safety Agency Accused of Lax Enforcement,” New York Times, March 12, 1987.

David S. Hilzenrath, “Mine Safety Nominee Defeated,” Washington Post, August 6, 1987.

Steven Greenhouse, “Rise in Mining Deaths Prompts Political Sparring,” New York Times, July 26, 2002.

Press Release, U.S. Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions, “Kennedy, HELP Committee Leaders Schedule Visit to West Virginia; Will Meet Sago Mine Families, Mine Workers; Check Progress of Investigation,” January 19, 2006.

“Senators Pay Visit to Sago Families: Jay, Ted Kennedy, Two From GOP, Vow to Find Answers for Victims’ Families,” Charleston Gazette (Charleston, WV), January 21, 2006.

Ian Urbina and Andrew W. Lehren, “U.S. Is Reducing Safety Penalties for Mine Flaws,” New York Times, March 2, 2006.

Pamela M. Prah, “Coal Mining Safety: Are Underground Miners Adequately Protected?,” CQ Researcher, Washington, DC: Congressional Quarterly Press, March 17, 2006 • Volume 16, Issue 11.

Emily Bazar, “Lawmakers on Both Sides Aim to Prevent Mine Disaster,” USA Today, May 17, 2006.

Alex Chadwick, “Sen. Kennedy on Mine Safety, Bush in Iraq,” Day To Day/NPR.org, June 13, 2006.

“Sago Mine Disaster,” Wikipedia.org.

Jan Austin (ed.), “Deaths Prompt Mine Safety Rewrite,” CQ Almanac 2006, Washington, DC: Congressional Quarterly, 2007.

Michael Rubinkam and Chelsea J. Carter, AP, “Senate Plans Hearing on Mine Collapse,” Washington Post, Thursday, August 23, 2007.

Thomas Burr, “Mine Probe: Congress Begins Crandall Canyon Cave-in Investigation,” The Salt Lake Tribune, August 23, 2007.

Thomas Burr, “Kennedy Blasts Mine Communication Breakdown at Crandall Canyon,” The Salt Lake Tribune, October 2, 2007.

U.S. Government Printing Office, S. Hrg. 110-730, “Current Mine Safety Disasters: Issues and Challenges,” Hearing of the Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions, United States Senate, One Hundred Tenth Congress, First Session, on Examining Issues and Challenges Facing Current Mine Safety, October 2, 2007.

Spencer S. Hsu, “Report Faults Mine Safety,” Washington Post, November 17, 2007.

Press Release, Senator Edward M. Kennedy, “Kennedy Releases New Report on Crandall Canyon Mine Disaster,” March 6, 2008.

Suzanne Struglinski, “Mine Report Pulls No Punches; Criminal Probe of MSHA, Murray Energy Urged,” DesertNews.com, March 7, 2008.

Thomas Burr, Robert Gehrke and Mike Gorrell, “Beyond Crandall: Feds Found Negligent; MSHA Fails Miners Nationwide, Probe Finds,” The Salt Lake Tribune, April 1, 2008.

“Crandall Canyon Mine,” Wikipedia.org.

John Hollenhorst, “Crandall Canyon Mine Memorial Unveiled,” KSL.com, September 14th, 2008.

“Interview with Thomas M. Rollins,” The Miller Center Foundation and the Edward M. Kennedy Institute for the United States Senate, EMKinstitute.org (Rollins discusses Senate confirmations, mine safety, the minimum wage and other Labor Committee topics), May 14, 2009.

John M. Broderaug, “Edward M. Kennedy, Senate Stalwart, Is Dead at 77,” New York Times, August 26, 2009.

Emery Jeffreys, “Kennedy, Working People’s Champion,” bytewriter.com, August 26, 2009.

Ken Ward Jr., “Sen. Edward Kennedy: A Friend to Coal Miners,” Gazette-Mail (West Virginia), August 28, 2009.

Davitt McAteer, “Mine Industry Is Gutting Safety Regulations,” Charleston Gazette-Mail, April 5, 2015.

_________________________

Robert F. Kennedy, Jr.

Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., Website.

“Robert F. Kennedy, Jr.,” Wikipedia.org.

Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., “Crimes Against Nature,” Rolling Stone, December 11, 2003.

Amanda Little, “An Interview With Robert F. Kennedy Jr., Environmental Advocate and Bush Basher,” Grist, July 14, 2004.

Robert F. Kennedy, Jr:, Crimes Against Nature: How George W. Bush and His Corporate Pals Are Plundering the Country and Highjacking Our Democracy, New York: HarperCollins, 2005.

David Brancaccio, “Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. and Mercury in Fish,” NOW(PBS), January 21, 2005.

Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., “King Coal Pillages Beautiful Land,” iLoveMountains.org, Sep-tember 10, 2006 (reprinted from Waterkeeper Magazine, Winter 2006).

Marnie Hanel, “Is ‘Clean Coal’ a Dirty Lie?,” Vanity Fair, February 27, 2009.

Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., “Hope in the Mountains,” Washington Post, March 25, 2009.

Brian Ross, “Interview with Robert F. Kennedy Jr.,” ABC News, April 14, 2009.

Brian Ross and Joseph Rhee, “RFK Jr. Blasts Obama as ‘Indentured Servant’ to Coal Industry,” ABC News, April 21, 2009.

Robert F. Kennedy, Jr:, “A President Breaks Hearts in Appalachia,” Washington Post, July 3, 2009.

Ucilia Wang, “Robert Kennedy on Being Subversive,” GreenTechMedia.com, October 28, 2009.

Ken Ward Jr., “RFK, Jr., Coal Baron Spar Over Mountaintop Removal, Climate Change; Blankenship, Kennedy Debate Coal’s Future,” Charleston Gazette (West Virginia), January 22, 2010.

Tom Zeller Jr., “Energy Debate Yields Little Middle Ground,” New York Times, January 22, 2010.

David Roberts, “Robert F. Kennedy Jr. Takes on Mountaintop-Mining Magnate Don Blankenship,” Grist.com, January 22, 2010.

Rob Perks, “Mountaintop Removal Redux: Bobby vs. Blankenship II,” NRDC.org, March 11, 2010.

Reuters, “Bobby Kennedy Jr. Battles Big Coal in U.S. Documentary,” Reuters.com, June 6, 2011.

Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., Senior Attorney, Natural Resources Defense Council, “Remarks at The Commonwealth Club,” Commonwealth Club.org, San Francisco, June 16, 2011.

“Citizens March to Protect Hallowed Ground on Blair Mountain,” SierraClub.org (Sierra Club Scrapbook), June 28, 2011.

“The Last Mountain,” Wikipedia.org.

Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., “The Fracking Industry’s War On The New York Times — And The Truth,” HuffingtonPost.com, October 20, 2011.

Jim Deming, “Robert F. Kennedy, Jr.: The Real Deal,” Front Porch Blog, AppVoices.org, October 31, 2011.

Bryan Walsh, “Drawing Battle Lines Over American Coal Exports,” Blogs.Time.com, May 31, 2012.

Bruce Henderson, “Environmental Groups Target Coal Ash,” The Charlotte Observer (McClatchy-Tribune Regional News), July 24, 2013.

Donna Lisenby, Waterkeeper Alliance, “Environmental Leaders Expose How the Coal Industry Poisons Our Water,” EcoWatch.com, July 25, 2013.

Alan Hodge, AP, “Kennedy Visits Coal Ash Ponds, Tears into Duke Energy,” Banner-News.com (North Carolina), July 31, 2013.

Mary Anne Hitt and Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., “Will EPA Protect Our Families From Toxic Coal Water Pollution?,” EcoWatch.com, August 6, 2013.

Kimberly Johnson, “Coal Leaves Deep, Wide Wake in West Virginia,” America. Aljazeera.com, March 24, 2014.

Cheryl K. Chumley, “RFK Jr Wants Law to Punish Global Warming Skeptics,” Wash-ington Times, September 23, 2014.

Wendy Koch, “Kennedy Home Gets Green Makeover,” USA Today, January 27, 2010.

Kris Kitto, “20 Questions With Robert F. Kennedy, Jr.,” The Hill.com, June 1, 2011.

Bruno Navasky, The V.F. Interview, “Robert F. Kennedy Jr. on the Environment, the Election, and a “Dangerous” Donald Trump,” Vanity Fair, August 11, 2016.

Michael Lee Nirenberg, “Conversation with Robert F. Kennedy, Jr.,” HuffingtonPost.com, May 22, 2017.

Dan Zukowski, DC News Bureau, “Robert F. Kennedy Jr.: ‘If You Believe in Markets, You Have to Believe the Era of Coal Has Ended’,” EnviroNews.TV, June 27, 2017.

______________________________________