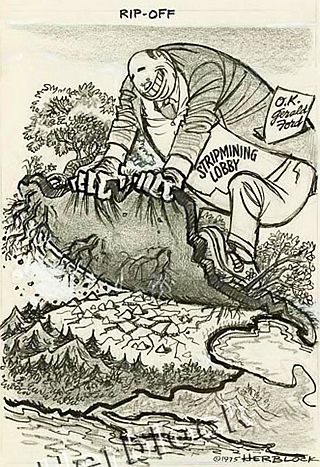

June 1, 1975. Washington Post / Herblock cartoon, “Rip-Off,” with pointed message about strip mining lobby in Congress during legislative battle to enact strip mining controls.

Ford would veto two successive strip mining reclamation bills sent to him by the U.S. Congress – one in December 1974 and another in May 1975 – bills that had gone through months of arduous debate and years of grass roots political activity.

The Washington Post, meanwhile, would mark the latter Ford veto in June 1975 with a political cartoon from its famous lampooner, “Herblock” (Herbert Block), shown at right.

In the cartoon, Herblock attacks strip mining interests by depicting a man, representing the strip mine lobby, literally peeling off the Earth’s crust across America, with an “O.K” note from “Gerald Ford” sticking out of his pocket.

Herblock’s message is clear: the President was then in the pocket of the coal interests and their lobbyists.

More on the Ford vetoes and coal-industry lobbying tactics a bit later – including a famous “protest convoy” of 400-plus coal trucks that barreled through Washington, D.C. in the spring of 1975 seeking to block the needed law. But first, some background.

“Rape & Scrape”

By the 1970s, surface coal mining in America was occurring in 26 states. The practice – then poorly regulated in most states, if at all – had been ravaging the nation’s land and waters for decades. In Appalachia, mountainsides were ringed with thousands of miles of scars from contour stripping. Some 20,000 miles of unreclaimed and dangerous “highwall” cuts from contour mining were found in Appalachia alone. Surface mining in some locations had snaked around hillsides as far as the eye could see (photo below). In the process, mine spoil was simply pushed “over the side” — down mountain slopes — silting up and polluting streams below. Thousands of miles of creeks and streams suffered ill effects: some filled with sediment, others acidified from mine spoil seepage, many devoid of fish and other aquatic life.

1967. Aerial view of contour strip mining's handiwork in Eastern Kentucky, with gouged-out mountainside scars running for miles to the far horizon. Source: “These Murdered Mountains,” Life, January 12, 1968, photo by Bob Gomel.

Landslides from contour strip mining sometimes wiped out down-valley homes. Flooding of the narrow bottom lands was often made worse by the strip-mined, denuded hillsides. Blasting at mine sites would sometimes crack the walls of nearby homes or knock them off their foundations. Local roads were also torn up, forests clear cut, and wildlife habitat ruined.

Photo from 1968 U.S. Interior Dept, Fish & Wildlife Service study of strip mine “highwall” left after mining. The original caption read: “Access to more than 400,000 acres of wildlife habitat is impaired by highwalls in West Virginia. This unscalable highwall is in Randolph County”.

In the flat-to-rolling lands of the Midwest – especially Illinois and Indiana – millions of acres of fertile agricultural land were underlain with strippable coal, prompting concerns that even if these lands were reclaimed after mining, they would never again be as productive for row-crop farming.

This giant strip mine shovel began work in 1962 at the Sinclair Mine in western Kentucky for Peabody Coal Company. Note small pick-up truck and bulldozer, lower right, dwarfed by the gigantic shovel.

Also within the coal industry at the time, was a changing investment and economic development – something called “the East-West shift” – meaning a movement away from high-cost, deep-mineable, union-dug coal in the East, to large-tracts of federally-leased coal lands in the West with thick seams that could be dug more cheaply with surface- and open-pit-mines, giant machines, and non-union labor. Eastern deep-mined coal, however, was more energy dense (more BTUs), and on that basis, when burned, less polluting. Deep-mined Eastern coal also offered longer-term local investment, more jobs, and community stability. Still, the coal industry was being lured West, but regardless of location, would fight to keep any new regulation at bay.

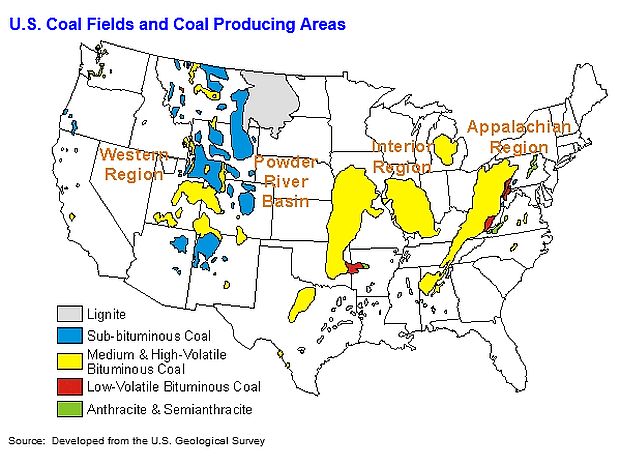

This U.S. Geological Survey map of U.S. coal fields provides a generalized look at where the nation’s coal reserves are located, color coded by grade and type of coal, with 26 states having at least some coal and mining activity.

In the Montana/Wyoming/North Dakota area on the above map — and in particular, the blue-gray areas straddling those three states – is known geologically as the Fort Union Formation, which holds enormous quantities of coal. In the early 1970s, the coal within “strippable reach” in this formation was estimated at about 100-billion tons, or roughly, 40 per cent of the country’s “known reserves” at the time. Coal in the western North Dakota portion of the Fort Union formation, shown in gray on the map, is lignite, where extensive strip mining would also occur, as shown in the photo below.

Extensive strip mining operation in the lignite coalfields of western North Dakota, showing extraction at uncovered coal seam, as well as spoil piles of removed overburden. Photo is likely from 1960s-1970s era.

Coal in the Powder River Basin portion of the Fort Union Formation – the blue area on the above map shared by eastern Montana and northeast Wyoming – includes quite large deposits of strippable coal, with dozens of long-running seams, some as thick as 100 feet or more.

The federal government, coal and utility companies meanwhile, eyeing the Fort Union cache, had offered some grandiose visions of what might happen in that region by way of industrial and electric power development. The “North Central Power Study” of 1971, for example, written jointly by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation and 35 major utilities, came like a bolt of lightening to Northern Great Plains ranchers. It proposed 42 coal-burning “mine-mouth” power plants that would export electricity by high-voltage transmission lines to other areas. Twenty-one of the plants would be in Montana fueled by big strip mines. It also projected using 2.6 million acre-feet of water annually from western rivers such at the Yellowstone for power plant cooling and coal cleaning. The impacts of such a plan, if implemented – with assorted rail spurs, pipelines, and power lines – would be massive. Rancher-based citizen groups, such as the Northern Plans Resources Council in Montana, soon formed in response.

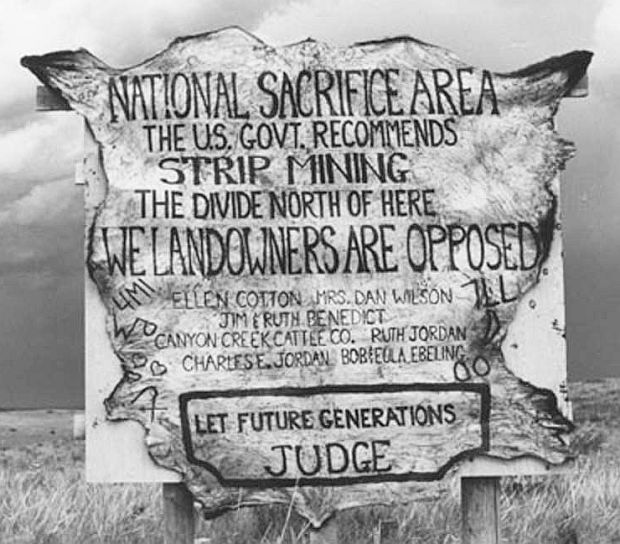

By the time of the North Central Power Study in late 1971, ranchers in Montana were making it known where they stood on plans to strip mine and industrialize their region, calling it a “national sacrifice area” with protest signs like this one in Montana.

More than a million acres of western federal and Native American coal lands were already under lease by 1971, with another million acres under prospecting permits. In the East as well, the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), since the 1960s, had spurred new strip mining throughout Appalachia by offering long-term contracts to coal operators. Giant shovels in the East had already been tearing up the land in Ohio, Pennsylvania, Kentucky, West Virginia, southwest Virginia and Tennessee for decades.‘Uppity’ Appalachian land- owners who objected to coal claims, or tried to defend their property – some in armed stand-offs – were sometimes met with beatings, arson, and/or jail time.

In some coal states, most notably Kentucky, the “broad form deed” was in use, a nefarious property document, that gave mineral owners the right to run roughshod over the surface owner to get to the coal. “Uppity” Appalachian landowners and activists who objected or tried to defend their property – some in armed stand-offs – were sometimes met with beatings, arson, and/or jail time.

In Western states too, “split estate” ownership between mineral owner and surface owner was also a volatile issue – in part due to a complicated history of land ownership, including: Native American tribal lands, government-owned lands, and railroad land grants (the latter making Northern Pacific heir, Burlington Northern, the nation’s largest corporate owner of coal resources in the early 1970s). Surface owners – ranchers in particular — wanted the right to “written consent” before near-surface coal lands could be mined or leased for mining. In addition, ranching operations were often dependent on alluvial valley aquifers, water-bearing sub-surface strata that often ran through, or were coincident with, thick, strippable coal seams in many of the coal-bearing western states, which if mined would alter hydrological systems. Scant rainfall in the West would also make post-mining reclamation challenging to say the least. Re-establishing the preferred native grasslands on the plains following strip mining was not a likely prospect.

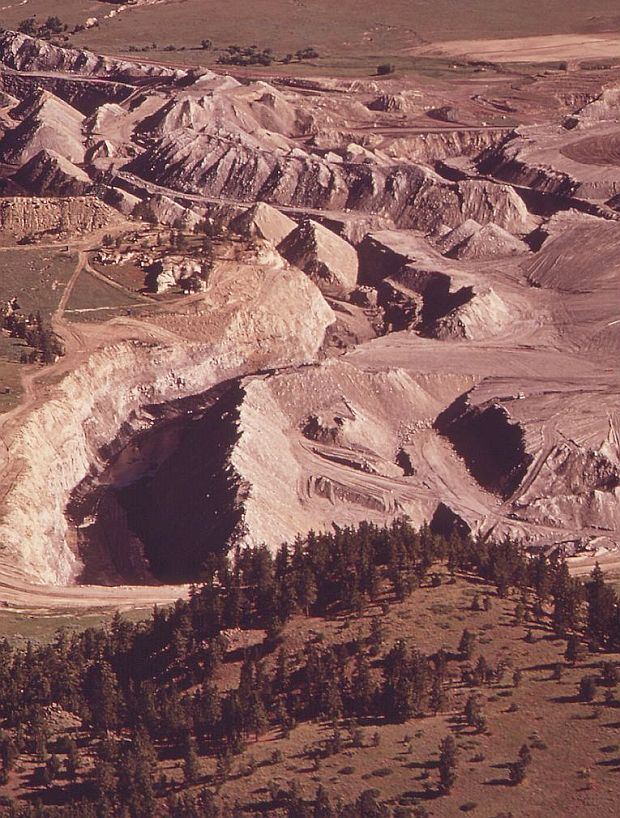

Large scale strip mining had begun at Colstrip, Montana in the late 1960s. This EPA photo shows a Peabody Coal Company strip mine operation, and aftereffects, at Colstrip in 1973.

Large-scale strip mining and coal-fired power development was also under way in the “Four Corners” region of the U.S. Southwest, where Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado and Utah intersect. Six huge coal-burning electric power plants were then being planned for the area, two of which were then on-line, with the others scheduled for 1974-1980. About half of the power would be sent to Southern California. The Four Corners projects were begun by a consortium of 23 power companies. As much as 40,000 megawatts of coal-fire generating capacity was seen as possible by 1985. The two existing plants then used strip-mined coal, also projected to feed future plants. Peabody Coal Company then held a lease on more than 60,000 total acres of lands either jointly or separately owned by Navaho and Hopi Indians, all on sacred Black Mesa lands. Some 337 million tons of bituminous coal was then estimated to exist there over about 100 square miles.

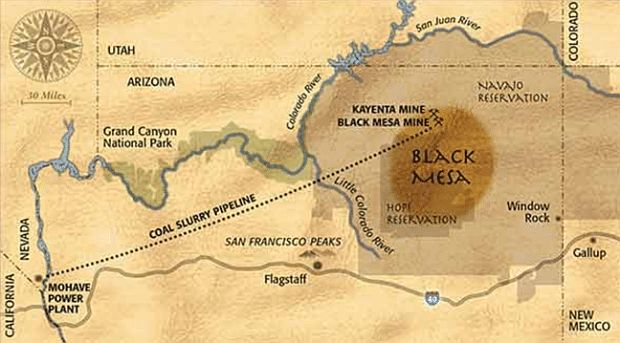

Map shows general location of two Peabody strip mines on Navajo-Hopi lands at Black Mesa in northwest Arizona, which opened in 1970 and 1973, exporting coal via slurry pipeline in one case for electric power production in Nevada.

A Peabody subsidiary began strip mining on the Black Mesa in the mid-1960s. Peabody later developed two large strip mines there – the Black Mesa mine on 20,775 acres, opened in 1970 (supplying the Mohave Generating Station in Laughlin, Nevada via a 275-mile coal slurry pipeline), and the Kayenta mine, on 44,073 acres, opened in 1973. Peabody’s lease came through tribal councils, not always representing majority Indian views. And like the Northern Great Plains, the Four Corners energy development plans aroused controversy over water resources, air pollution and land use.

Another huge problem in many of the Eastern coal states, but not limited to them, were abandoned mines – of both the surface and underground or “deep-mine” variety – where no reclamation had occurred, with old sites left to fester with acid-mine drainage that would pollute for years. The federal bills included proposals for a small tax on coal to help pay for an Abandoned Mined Lands Fund that would establish a national program to begin reclaiming thousands of these sites.

All of these issues, and others outlined above, would figure into citizen calls for action at the federal level, fueling subsequent Congressional debate through the early and mid-1970s.

Citizen Action

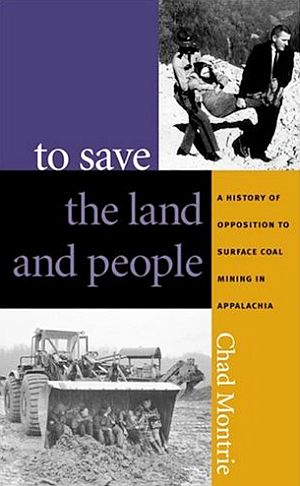

Chad Montrie's history of citizen opposition to strip mining in Appalachia, University of North Carolina Press, 245 pp. Click for copy.

Still, there is a very rich, decades-long history of citizen action and protest – whether in Appalachia, the Midwest, Northern Plains, or Native American land – that figures prominently in the crafting of strip mine regulation. Only a portion of that history is offered here to provide some context, and a fuller account is covered elsewhere (see, for example, any number of books and articles on the subject, some of which are listed below in Sources, and for Appalachia as one example, see Chad Montrie’s To Save The Land and People, which covers the activism, protests and politics from that region that fed into the Congressional battles of the 1970s).

Federal bills to deal with strip mining had been introduced in Congress as early as 1940 – with Republican Senator Everett Dirksen of Illinois, who saw his state’s agricultural lands being torn up, introducing the first such bill. That bill required operators to post a bond until the mined land was reclaimed. But neither Dirksen’s, nor any of the 40 or more other bills introduced between then and 1970 made much progress. Indeed, the first Congressional hearings on the matter weren’t held until 1968.

However, by the time of Earth Day 1970, when national environmental concerns began to rise, a new nationwide political coalition formed to push for a federal strip mine law. Appalachian activists, Midwest farmers, Northern Plains ranchers, and Native Americans joined with national environmental organizations, such as the Sierra Club and the Environmental Policy Center (EPC) in Washington, to lobby Congress, forming the Coalition Against Strip Mining, led by Louise Dunlap of EPC.

Ravaged landscape in Southeast Ohio with meandering highwall following strip mining there. 1974 photo, EPA/Erik Colonius.

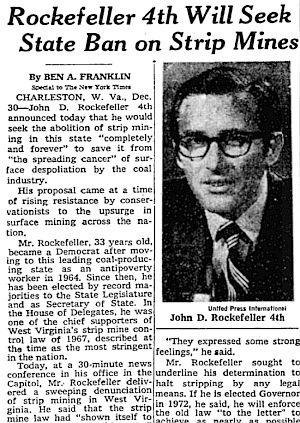

In West Virginia, John D. “Jay” Rockefeller, great-grandson of the famous Standard Oil tycoon, would also oppose strip mining. He had come to the state in 1964 as a VISTA social worker, was elected to the state House of Delegates in 1966 and then West Virginia Secretary of State in 1968. Rockefeller, along with activist Richard Cartwright Austin and state senator Simon Galperin helped create Citizens to Abolish Strip Mining (CASM), which Austin headed, Rockefeller funded, and Galperin worked in the West Virginia Senate to advance a strip mine abolition bill, introduced in January 1971. Rockefeller, for his part, had called a press conference in December 1970 as Secretary of State saying he would seek a bill to ban strip mining in West Virginia, testified in the legislature in support of the bill, which after being reworked and weakened in the legislative process, emerged in March 1971 as a temporary moratorium measure applying only to counties without coal reserves or where not active mining was then occurring. Still, the very fact that a strip mine prohibition was even debated at all in a state like West Virginia – then among the nation’s top coal producers — was something of a victory for its backers. Rockefeller continued to advocate for a strip mine ban in the state during his 1972 run for Governor.

|

“Must Be Abolished”  Dec 30, 1970 NY Times story on John D. Rockefeller’s call to abolish strip mining in West Virginia. …Government has turned its back on the many West Virginians who have borne out of their own property and out of their own pocketbooks the destructive impact of stripping. We hear that our Governor once claimed to have wept as he flew over the strip mine devastation of this state. Now it’s the people who weep. They weep because of the devastation of our mountains, because of the disaster of giant high walls, acid-laden benches, and bare, precipitous outslopes which support no vegetation at all but erode thousands of tons of mud and rocks into the streams and rivers below. Strip-mining must be abolished because of its effect on those who have given most to the cause – the many West Virginians who have suffered actual destruction of their homes; those who have put up with flooding, mud slides, cracked foundations, destruction of neighborhoods, decreases in property values, the loss of fishing and hunting, and the beauty of the hills. And we are not alone in our feeling. West Virginians love their hills. We identify ourselves with our hills, and are not about to let our hills be torn aside and demolished so that a small fraction of the coal beneath them can be taken away. And we can make a difference. But if we are to communicate as an abolition movement, we have to stretch ourselves further. It’s not enough just to be against strip-mining. In the emotion of seeing a newly clobbered hill, it’s easy to forget the largest justification for abolition. The strongest arguments, other than environmental ones, can be made for abolition on economic terms. And we have to manifest concern for new industries and jobs in West Virginia…. The overwhelming percentage of our coal can only be obtained by deep mining. . . And we know that when the industry is cured of its binge of exploitation stripping, and returns to real mining, there will be more jobs for West Virginians – jobs that contribute to our prosperity without destroying the communities and counties in which they are located. We can be a powerful force toward both halting the destruction of our state and also toward coming up with economically sound alternatives that will demonstrate best to all people that we have the long-term economic interests of the state at heart. Rockefeller won the Democratic nomination for Governor in 1972, but was defeated in the general election by the Republican incumbent, Governor Arch Moore. His abolition measure had brought new visibility and attention to the issue, but Rockefeller believed it cost him the election, and thereafter would not oppose strip mining again. In 1976 he was elected Governor of West Virginia, re-elected in 1980, and then became U.S. Senator in 1984, serving in that post to January 2015. |

Congressman Ken Hechler (D-WV).

In Congress, 1971-72

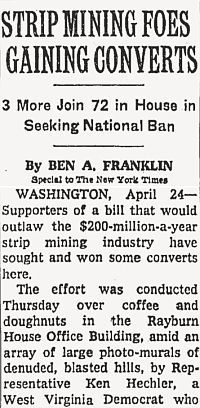

In Congress, meanwhile, over a dozen strip mine bills were introduced in 1971, including one by the Nixon Administration. But it would be the bill introduced by Rep. Ken Hechler (D-WV) that would receive the most attention. Hechler’s bill, H.R. 4556, proposed to prohibit new strip mining and phase out all surface coal mining in six months.

Hechler would later enlist 87 cosponsors on his bill, and by May 1971, a companion bill, S. 1498, was introduced in the U.S. Senate by Senators Gaylord Nelson (D-WI) and George McGovern (D-SD).

During hearings held on those bills and others, there was passionate support for Hechler’s bill to ban strip mining from many Appalachian activists and other citizen groups.

April 1971 NY Times news clip.

But in the end, as in Kentucky and West Virginia, there would be no quarter in Congress for banning or phasing out strip mining, as the oil/coal/utility axis was just too powerful.

From the coal industry, came a statement from Carl E. Bagge, president of the National Coal Association, charging that abolitionist efforts were “utterly ridiculous,” and would deny electric companies one-third of coal deliveries then coming from strip mines. Such restrictions, he said, would make electric power “brownouts and even blackouts inevitable in many heavily populated areas.”

Still, the fear of a national groundswell for prohibiting strip mining had made mining and energy interests somewhat more receptive to strip mine regulation – but certainly, the weakest possible regulation they could get. Yet even some Nixon Administration officials would concede of strip mine problems.

During two days of Senate hearings on the strip mine bills in November 1971, run by Senator Frank E. Moss, Democrat of Utah, some Nixon Administration officials, while not supporting strip mine prohibitions, did offer some situations for restrictions where the environment would be permanently impaired or unable to meet certain standards. Russell E. Train, chairman of the President’s Council on Environmental Quality, noted in one exchange: “Under some circumstances, [where] the damage from mining could not be repaired … Under those particular circumstances, it would be quite expected that mining could not be undertaken.” In another exchange between Senator Clifford P. Hansen (R-WY) and John R. Quarles Jr., of the EPA, Hansen asked: “Is it feasible at a given site to carry out mining activities without violating water quality standards or unduly impairing other important environmental values?” Quarles replied, “If not [i.e., unable to mine without violating standards], mining should be prohibited.” Yet, without exception, Nixon officials and those who testified for the mining industry in the Senate, and earlier in the House, strongly opposed as “unrealistic” and “potentially disastrous to the national economy” any flat prohibitions on strip mining.

Appalachian activists, however, were clear about where they stood. Jim Branscome, who headed the Save Our Kentucky citizens group and also spoke for the broader Appalachian Coalition, had testified in support of banning strip mining. Branscome, in fact, warned Congress that strip mining in Appalachia – and the apparent lack of control over it, despite appeals to local courts and state legislature — was creating a revolutionary fervor among coalfield residents, to the point of direct action against local mines and even taking up arms. Branscome also noted that perhaps even more important than strip mining’s environmental destruction, was its economic and social impacts on local residents and communities; its affront to human welfare and property rights. Later that year, on December 21, 1971, Branscome would also publish a long article on Appalachia strip mining for the Sunday New York Times Magazine – a story that was featured on the magazine’s cover, helping elevate the issue nationally.

December 12, 1971 cover of NY Times Magazine feature story on surface coal mining, showing aerial photo of “windrows” of huge spoil-piles left after power-shovel stripping in Kentucky. The Times story was written by journalist/activist James Branscome of Save Our Kentucky citizens group.

As Congress was considering the various strip mine bills, tragedy struck the coalfields in late February 1972 when a series of mountain-side coal waste dams failed at Buffalo Creek, West Virginia, killing 125 people. Congressman Ken Hechler, visiting the disaster scene that February, noted: “As I looked through Buffalo Creek valley yesterday, it struck me again that the entire valley is honeycombed with strip mines and the waste from deep mines so that the soil can no longer hold the [rain] water.” A citizens’ report on the Buffalo Creek disaster also noted that strip and augur mining above the coal dam had likely contributed to its over-filling. Unable to win an outright ban on strip mining, some sought a prohibition on “steep slopes.”The disaster helped raise public concern about coal mine safety, and also spurred some Congressional support for strip mine controls.

Still, Ken Hechler and supporters, not able to win a prohibition measure in Congress, were trying for a bill that would include a prohibition on strip mining steep slopes – those greater than 14 degrees. A New York Times editorial of August 1972, supporting such a measure, noted: “an effective bill will have to ban, within the shortest possible time, all surface mining on mountain slopes, where the greatest harm is done with the least chance of genuine reclamation.” But even the “steep slopes” ban could not gain traction in Congress, and instead certain regulatory requirements for handling overburden and spoil on such slopes would be added later. Hechler and others also sought, unsuccessfully, to designate EPA as the administrator rather than the Department of the Interior, the latter seen as too closely tied to mining and energy interests.

In the end, for 1972, a regulatory bill was passed out of the House Interior Committee, and approved by the full House on October 12. On the Senate side, a much broader bill was introduced by Senator Henry Jackson (D-WA), which covered all minerals and not just coal. That bill was voted out by the Senate Interior Committee on September 1972, but never made it to the Senate floor before Congress adjourned. So, no strip mine bill emerged from the 92nd Congress.

In Congress, 1973

President Richard Nixon, who would soon be dogged by the Watergate scandal (see sidebar, later below), had been reelected in November 1972, and his administration had sent a strip mining bill to Congress in early 1973. Although redrafted a few times in attempts to make it more palatable, the Nixon bill lacked key provisions – such as that for eliminating final cut “highwalls,” and it also had no program for cleaning up the tens of thousands of acres of abandoned, unreclaimed strip mine sites. The Democrat-controlled House and Senate committees would fashion the bills that were later advanced by Congress.

U.S. Senate Majority Leader (1961-1977), Senator Mike Mansfield (D-MT).

Among Senators commenting at the time was Senate Majority Leader Mike Mansfield (D-Montana) who told the committee: “We (of Montana) are not interested in becoming another Appalachia … [W]e are not going to stand by and let the large fuel corporations dig up eastern Montana until the reserves are exhausted.” As Senate leader, Mansfield vowed to press for “speedy passage” of a strong strip mining bill, adding at one point, that “a moratorium may be the answer” until a law and regulations were in place.

Edwin R. Phelps, president, Peabody Coal Company, declared that “the public interest includes not only reclamation but the right of interstate commerce to use” coal. Any undue restrictions on strip mining, he said, that would inhibit the development of this resource, would represent “economic waste of the grossest sort…”

The American Mining Congress spokesman was particularly concerned with a provision requiring coal mining operators to restore land after mining to “the approximate original contour” with “all highwalls, spoil piles, and depressions eliminated.” The provision was added in an amendment by Sen. Gaylord Nelson (D Wis.). Minimum federal standards for mining and reclamation were also part of Senate bill, S-425.

Senator Lee Metcalf (D-MT), a subcommittee chairman, who had his own bill, presided over most of the ten days of Senate Interior Committee “mark up” of S. 425, combining it with elements of his own bill, and changing the bill’s focus from “all minerals” to coal only.

Louise Dunlap of the Environmental Policy Center was a key lobbyist for citizen groups.

On the House side, two Interior subcommittees — the Environment Subcommittee (chaired by Rep. Morris Udall (D-Az) and the Mines and Mining subcommittee (chaired by Rep. Patsy Mink D-HI) held joint hearings during April and May 1973 on more than a dozen strip mine bills that had been introduced, including H.R. 1000 by Ken Hechler, to phase out strip mining. In mid-1973, some House members also visited strip mine operations at eastern and western locations.

Rep. Patsy Mink (D-HI), chair of Interior Mines & Mining Subcommittee.

In the Senate, S. 425 had been reported out of committee on September 21, 1973. Neither environmentalists nor the mining industry liked what they saw in that bill. When it reached the full Senate for two days of floor debate, October 8th and 9th, an amendment by Senator Mike Mansfield was offered to prohibit strip mining, but not deep mining, on federal coal lands where the government did not own the surface. Mansfield’s amendment passed by a 53-to-33 vote, but would later be removed in conference committee.

On October 9, 1973, the final senate bill passed by an overwhelming 82-to-8 vote, while withstanding an attempt to knock out the “approximate original contour” requirement — the bill’s central reclamation feature. Among the bill’s other provisions was one that would prohibit surface coal mining where reclamation was not feasible. States would have six months to develop strip mine regulations in accord with the bill, or have federal standards imposed. And $100-million was included for the reclamation of lands already stripped and $5-million a year in grants was set aside to help states developing their regulatory plans. But just as some progress was being made with strip mine legislation, a major new wrinkle in the energy-environment equation emerged: an Arab oil embargo.

|

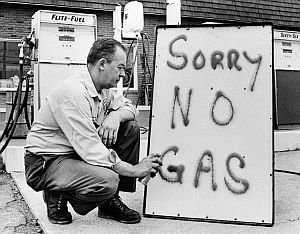

“Two Upheavals” As the strip mining legislation was being considered in Congress during 1972-74, two major national political upheavals were occurring – Watergate and the energy crisis. The first brought high political drama and a Presidential crisis to Capitol Hill and nation, and the second rattled national energy policy and brought economic travail. In retrospect, it’s a wonder anything of substance was able to move through Congress amidst these major calamities.  August 9, 1974. Famous farewell moment from Richard Nixon at helicopter door upon his departure from the White House following his resignation from office.  1973. Gas station attendant bringing the bad news to would-be patrons following the Arab oil embargo. In the U.S., between 1970 and 1973, imports of crude oil had nearly doubled, reaching 6.2 million barrels per day in 1973, making the nation vulnerable to supply disruptions. With the Arab oil embargo, a U.S. “energy crisis” soon ensued. Long lines of cars began appearing at gasoline stations as supplies became limited or ran out. “No gas” signs appeared, then gasoline was rationed. “Gas guzzler” automobiles stopped selling, Detroit was staggered, speed limit restrictions were imposed, calls for energy conservation abounded, as ill effects rippled through the stock market and broader economy. About a month later, on November 7th,1973, the Nixon Administration then called for a national “Project Independence” energy initiative in reaction to the OPEC oil embargo, invoking the Manhattan Project, with the goal of achieving U.S. energy self-sufficiency by 1980 through a national commitment to energy conservation and alternative energy development. Coal development and nuclear energy became major parts of that plan, later unveiled by Henry Kissinger on February 11, 1974.  AEP’s cartoon-styled logo and slogan that ran with many of its 1974 ads pushing coal development. |

Back in Congress…

Back in Congress, meanwhile, the House Interior committee began its mark up of H.R. 11500 in February 1974, beating back one attempt to substitute a weaker version by Rep. Craig Hosmer (R-CA). The committee conducted some 19 days of mark-up before voting the bill out on May 14, 1974.

During House floor debate of July 1974, Patsy T. Mink (D Hawaii), chair of the Mines & Mining Subcommittee said there was “absolutely no merit” to the coal industry’s “scare tactic” that the bill would “shut down coal mines and reduce production to a point electric power blackouts.” She contended that HR 11500 was similar to stiff surface mining laws in Ohio and Pennsylvania where coal production had actually increased and miners had not been thrown out of work.

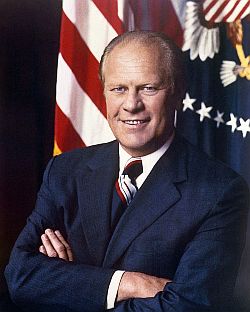

1974 portrait of President Gerald R. Ford.

By August 9, 1974 Gerald R. Ford was President of the United States, having assumed the Presidency with Richard Nixon’s resignation over the Watergate scandal.

In Congress, the House and Senate versions of the strip mine bills were similar in their major provisions but contained several important differences, and these would be worked over during the House-Senate conference on the bills. The conference committee met 20 times between August 1st and December 3rd, 1974 when agreement was finally reached. Full House approval of the conference report followed on December 13th, with Senate approving final passage on December 16, 1974. “The Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act” was then sent to the White House for the President’s signature.

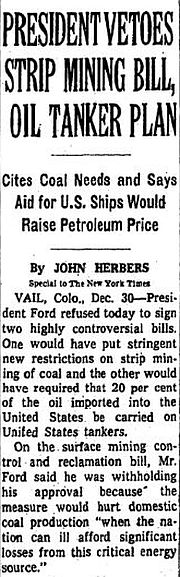

Dec 1974 New York Times reporting on President Ford’s vetoes.

Ford’s 1st Veto

President Ford had made it known he would veto any strip mine bill that came to him. His energy advisers had prevailed internally, concerned that strip mine reclamation rules would curtail coal production at a time when the nation was still in throes of an energy supply crisis, given its continued dependence on oil imports.

“We are engaged in a major review of national energy polices,” Ford wrote in his memorandum of disapproval for the strip mine bill. “Unnecessary restrictions on coal production would limit our nation’s freedom to adopt the best energy options.” The strip mine bill, he said, would increase U.S. dependence on expensive foreign oil.

Still, there had been some support within the Ford Administration for strip mine regulation. Interior Secretary, Rogers Morton, and EPA’s Russell Train, had recommended the President sign the bill, with Morton predicting Congress would pass an even more restrictive bill the following year. Environmentalists had also made some appeals to then Vice President Nelson Rockefeller, who had expressed concern about strip mining impacts in the West.

Nevertheless, by the time the bill reached the White House, President Ford simply ignored it, allowing a “pocket veto” to occur on December 30, 1974, as Congress by then had adjourned. And so, there would be no opportunity for Congress to attempt a veto override. While Congress is in session, the Constitution gives the president 10 days to sign or return legislation to Congress. If Congress adjourns during the 10-day period, and the president does not sign the bill, a “pocket veto” occurs.

In any case, what would have been “the preeminent environmental legislation of the 93rd Congress” according to Congressional Quarterly, was stopped in its tracks with Ford’s pocket veto. Now, the whole legislative process around the strip mining legislation would have to begin anew in the next session of Congress, beginning in 1975.

In Congress, 1975

Morris “Mo” Udall (D-AZ), a 1976 presidential candidate, would become a leader on strip mine bills.

In fact, in both the House and Senate, the previous bill that was pocket-vetoed by Ford became the starting point for new bills in each chamber. And to save time, the full committees took up the bills directly, by-passing subcommittees and only holding hearings for Ford Administration officials.

In early February 1975, President Ford had sent his bill to Congress along with a letter indicating certain “critical” and “other important” changes his administration sought in the previously vetoed bill. The House had three days of mark-up in late February 1975 during which some, but not all, of the Administration’s suggested changes were incorporated into their new bill, H.R. 25. That bill then went to the House for three days of debate, during which 42 amendments were considered and 22 adopted. A “steep slopes” prohibition measure modeled on an earlier Ken Hechler bill, to prohibit new mining permits on slopes greater than 20 degrees, was offered by Gladys Spellman (D-MD) on March 17, 1975, but defeated by a 262-to-136 vote. The full house then adopted H.R. 25 the next day on a vote of 333-to-86, with 96 Republicans in favor.

Sen. Henry Jackson (D-WA), also an announced presidential candidate for 1976, was sponsor of S.7.

Senator Henry M. “Scoop” Jackson (D-WA), Interior Committee chairman and chief sponsor of S. 7, would later call the bill “firm but fair,” denying assertions by the Ford Administration and the coal industry that it would significantly reduce coal production.

Even though the House and Senate had started with similar bills, there were still some 67 differences between H.R. 25 and S.7. These bills then headed to House-Senate conference committee to iron out the differences. It was April 1975. With the likelihood the strip mine bill would soon arrive at the White House, the coal industry decided to turn up the heat.

Coal Truck Protest

A contingent of some 2,000 strip mine workers and more than 400 coal trucks headed for Washington, D.C. in early April 1975. Their intention was to mount a protest at the Capitol to make their views known to lawmakers then writing strip mining legislation. They feared the bills would result in lost jobs and ruined local businesses.

The trucks and the miners came mostly from the coalfields of southwest Virginia and West Virginia, and part of their plan was to lobby their Senators and Representatives.

April 7th, 1975. A reported 30-mile long convoy of protesting coal trucks from southwest Virginia heads for Washington, D.C. via Interstate Highway to protest strip mining legislation in Congress. UPI photo.

One account of the trip to Washington from Southwest Virginia filed by United Press International (UPI) reported the following:

…The trucks looked like they carried an army off to war as they wound through the mountain roads of Appalachia. Hundreds of people lined the shoulders [of roads in local towns], holding signs and calling out encouragement. Two young girls stood on the crest of a hill holding a poster which read, “Good Luck in Washington, Coal Miners. We’re All Behind You.” A Wise County policemen held up a clenched fist. An old man flashed a “v-for-victory” sign with his fingers. “Give ’em what for,” shouted a woman. The caravan of coal operators, truckers and miners left for the nation’s capital Monday [April 7, 1975] in an effort to save their jobs and, possibly their counties’ economic well-being. They are in Washington…to protest the proposed federal strip mining law to overhaul and toughen reclamation regulations, particularly for coal scraped out of steep hills….Several store windows supported the strike with posters. “We’ve Got Coal, Let Us Mine It,” read a sign at the Corner Restaurant. Nick Voni, the owner, watched as the convoy passed. “Most of my business comes from coal workers,” he said. “If they go so do most of the little profit I now make”…

Coal truck departing for D.C. with home-made message.

The convoy, which began in southwestern Virginia with about 400 trucks, soon added others along they way from neighboring states, including West Virginia, Kentucky and Tennessee.

By the time they arrived in the Washington metro area on April 7, 1975, there were more than 400 coal trucks. Since the planned rally was scheduled for April 8th, they parked their rigs for the night in Alexandria, Virginia, across the Potomac River from Washington, with drivers and other demonstrators then shuttled by bus to hotels in Washington.

According to spokespersons for the two organizations representing the protest – the Appalachian Organization of Surface Miners and Truckers, and the Virginia Surface Mine Reclamation Association – they had petitions with 15,000 signatures urging President Ford to veto any strip mine bill that emerged from the Senate-House conference.

Once in D.C., the plan for the caravan was to form long lines of the large coal trucks that would move down Independence Avenue toward the Capitol, and also along Constitution Avenue from the Capitol to the White House. Others on foot at the Capitol would assemble into smaller groups of four or five to lobby members of Congress to oppose the strip mine bills then heading for House-Senate conference.

April 9, 1975. New York Times story on the “coal truck” protest in Washington, DC over then-pending strip mine bill in Congress, with one truck shown in foreground carrying sign, “Without Coal Nothing Will Roll.”

A number of the coal trucks on parade were emblazoned with home-made placards that read, “We Dig Coal,” “Coal Is Beautiful,” and “You Choose: Coal or Cold”. Others singled out the pending bills in Congress with messages such as: “Harlan Opposes S-7 HR 25,” “Let’s Kill S.7 and H.R. 25 on the Hill”, “Stop S.7”, and “Veto S-7, HR-25.”

Some of the protestors erroneously believed the legislation held provisions to ban strip mining on slopes of 20 percent or more. Such measures, they charged, would shut down up to 85 per cent of the strip mines in the mountainous areas of Southwest Virginia in Wise County, and most of the surface mines in nearby states. Wise County officials believed passage of a strip mine bill would spell ruin for their economy, closing stores and raising unemployment.

John Seiberling (D-OH), an Interior Commit-tee member, helped move strip mine bills.

Congressman Morris Udall called the protesters’ job fears the result of “a mischievous and purposeful effort by a misguided segment of the coal industry to mislead and foster fear among workers and their families.” Speaking to newsmen in his office at one point as the sound of blaring truck air horns could be heard from the truck protest on the nearby streets, he also said: “the sincere miners who are here have been misguided by a segment of the industry with a hell-be-damned attitude. They’re confused and mis-led people. . . . It’s a power play, nothing new in their presentation. They are people who want to keep on doing what they have done for 50 years,” which he called “raping the landscape.” The nation “has had it with them,” he said.

A few newspaper reporters who had been following the legislation in Congress, among them, Ward Sinclair of the Louisville Courier Journal and Ernest Furgurson of The Washington Star, detailed in their follow-up stories how the protesting miners were mis-informed about the contents of the strip mine legislation which was then headed for House-Senate conference.

Veto No. 2

May 20, 1975. NY Times story on President Gerald Ford's 2nd veto of strip mine bill.

On May 20th, 1975, Gerald Ford vetoed H.R. 25, the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1975, despite an overwhelmingly pro-environment vote in the House of Representatives. Ford argued that jobs would be lost, utility bills would rise, Americans would be more dependent on foreign oil, and coal production would be unnecessarily reduced. Now, however, a showdown would come between the President and Congress, as an attempt to override his veto would now be attempted.

Margins in both the House and Senate on previous votes on the bill and related amendments suggested there would be a two-thirds majority needed to override Ford’s veto. The House had voted 293-to-115 on final passage – 21 votes more than two-thirds. The Senate’s earlier vote on S. 7 had been 84-to-13. If those margins held, Congress would win. And so, a major lobbying battle ensued through early-and-mid June 1975, including an unusual joint House-Senate “veto justification” hearing by Udall and Jackson on June 3rd, 1975 attempting to pin down suspect data about job loss and reduced coal production used by the Ford Administration to justify the veto.

In its veto message, the Ford Administration claimed that 36,000 miners would be thrown out of work, electric bills for millions of consumers would rise, and as much as 162 million tons a year in coal production would be lost. At its joint hearing, the Democrats charged “funny numbers,” not being able to get satisfactory answers about sources or back up. Both Udall and Jackson issued statements attacking the data projections used in the Administration’s veto message. At the packed joint hearing on June 3rd, Udall accused Administration officials of “misleading” the President with knowingly “false and phony” estimates of the energy and economic impacts, and of manufacturing “false computations and statistics, in collusion with irresponsible coal interests and the electric utility industry.”Udall accused Administra-tion officials of “misleading” the President with knowingly “false and pho-ny” estimates. Those charges were denied by the officials during questioning by Republican committee members. Still, the dramatic hearing wasn’t enough to convince Congress to override Ford’s veto. On June 10th, 1975, the House failed to override Ford’s veto by a vote of 278-to-143, falling short by just three votes.

Later, however, two newspaper reporters then covering the strip mine legislation and the veto justification hearings — Ward Sinclair of the Louisville Courier-Journal and Stephen Nordlinger of The Baltimore Sun — conducted a joint three-week investigation of the data used by the Ford Administration for the veto, finding it full of contradictions, discrepancies, guess-work, and in fact, being quite “sloppy.” The reporters filed detailed stories in their respective newspapers on what they found on June 30, 1975 (Interestingly, two years later, Sinclair and Nordlinger were asked to testify and recount their investigations on the Ford strip-mine veto data before a Senate Interior Committee then considering legislation to create the Federal Energy Information Agency).

In any case, after the House lost the vote on the attempted veto override, Morris Udall told the press: “A large majority of the American people clearly want this bill…This thing isn’t dead. The fight must go on.” Indeed.

Sen. Lee Metcalf (D-MT).

Rep. John Melcher (D-MT).

On June 16, 1975, Senator Metcalf (D-MT) announced his intention to attach a good portion of the strip mine bill, including surface owners protection, to the then-pending Federal Coal Leasing Amendments Act of 1975, S. 391 (Metcalf did not include titles for abandoned mine reclamation title or state mineral research institutes). On July 31, 1975, just before the August Congressional recess, the Senate voted to approve S. 391 with Metcalf’s provisions, by a vote of 82-to-12.

A day earlier on the House side, John Melcher (D-MT), signaled his intention to do the same thing and more, attaching the entire vetoed strip mine bill, with no titles eliminated, to the House version of the Federal coal leasing bill, HR. 6721. The moves to attach strip mining regulation to the coal leasing bills was a clever strategy, as the Ford Administration wanted the coal leasing measures to pass. Yet, as it turned out, the Democrats were also foiled on this attempt. On November 12, 1975, as the House Interior Committee prepared to vote out their leasing bill, HR 6721, they refused to adopt the Melcher plan.

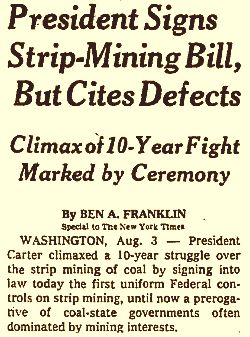

August 1977 New York Times story on bill signing.

In November 1976, Jimmy Carter was elected President. And in 1977 — after a repeat of the arduous legislative process in Congress all over again, including hearings, subcommittee and full committee mark-ups, House and Senate floors debates, more amendments, and much lobbying – President Carter, at an August Rose Garden ceremony that included many citizen activists from across the country, signed the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act 1977 into law. While the law wasn’t perfect from an environmental and citizen activist perspective — which Carter acknowledged — it did offer a decent starting point.

Still, enactment of the law – also known by its acronym, SMCRA, pronounced “smack-rah” – was just the beginning. Ferocious fights lay ahead over the law’s enforcement, including battles over various exemptions and loopholes in the law, ongoing litigation over the law’s key provisions, and recurring budget, personnel and political battles in managing the law in subsequent administrations and Congress.

This August 2007 joint report on the strip mine law by the Western Organization of Resource Councils and the Natural Resources Defense Council, offered a critical assessment.

In 2017, for example, Tom FitzGerald, director of the Kentucky Resources Council, one of a number of citizen groups tracking strip mine activities in Appalachia, noted: “…after 40 years of implementation, and fully sixty or more years after grassroots efforts to enact a national program for controlling surface coal mining, the promises made by Congress to the people of the coalfields remain largely unkept.”

And while coal’s role in national and global economies may be contracting with the realities of climate change, there are still ongoing battles every day in America over strip mining control, lack of reclamation, and abandoned mined-land repair.

In retrospect, however, the 1971-1976 era of shaping the strip mine law does offer a classic case study of the legislative and political process – of “how a bill becomes a law” – from grassroots organizing to White House maneuvering, and much more.

For more recent history, see “Sources, Links & Additional Information” below, along with more than a dozen books listed there on coal-mining topics.

Additional stories at this website on the history of coal and coal mining include the following: “Giant Shovel on I-70,” (about strip mining in southeastern Ohio during the 1960s and `70s); “Paradise: 1971″ (about a John Prine song, strip mining in Muhlenberg County, KY, and the demise of a small town); “Mountain Warrior” (profile of Kentucky author and coal-field activist, Harry Caudill, and his life-long critique of Appalachian strip mining); “Coal & The Kennedys, 1960s-2010s” (about the members of the politically-active Kennedy family of Massachusetts and their involvement in coal mining and related issues over 50 years); “Sixteen Tons, 1950s” (the famous Tennessee Ernie Ford song and some coal mining history); and, “G.E.’s Hot Coal Ad, 2005” (a General Electric TV ad that casts coal miners, coal mining, and coal burning in a misguided light).

Thanks for visiting – and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research, writing, and continued publication of this website. Thank you. — Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

____________________________________

Date Posted: 14 April 2022

Last Update: 14 April 2022

Comments to: jdoyle@pophistorydig.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Ford Helps Strippers: Two Vetoes,

1974-1975,” PopHistoryDig.com, April 14, 2022.

____________________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

Herblock (Herbert L. Block), cartoonist, “Rip Off,” Washington Post, June 1, 1975 (also appearing at U.S. Library of Congress exhibit, “Enduring Outrage: Editorial Cartoons by Herblock,” Washington, DC, 2006-2007 (from the Herbert L. Block Collection).

“Governor Requested To Halt Strip Mining,” The Mountain Eagle (Whitesburg, KY), September 1, 1960.

Harry Caudill, “Who Would Wreck a Valley for a Bit of Cheap Fuel,” Mountain Life & Work, Vol. 40, No. 3, Fall 1965 (remarks before White House Conference on Natural Beauty, May 24, 1965).

Ben A. Franklin, “Strip Coal Mines Vex Kentuckians; 70 Hold Motorcade, Picket Capitol and See Governor,” New York Times, June 23, 1965.

Jim Morissey, “The TVA – A Ravager?,” The Courier-Journal Magazine (KY), August 13, 1965.

Kyle Vance, “Knott Widow Hauled Off In Clash At Strip Mine” [ re: arrest of 61-year old Mrs. Ollie Combs for protesting a strip mine near her home], The Courier Journal (KY), November 24, 1965, front page (w/photo of Combs being carried off by two officers).

David Nevin, “These Murdered Old Mountains – Kentucky Operators are Violently Defacing the Land and Ruining Lives,” Life, January 12, 1968, Photographs by Bob Gomel, pp. 54-64.

“Northern Plains Resource Council, “History: Industrial-Scale Coal Mining in Ranch Country,” NorthernPlains.org.

Joseph A. Boccardy and Willard M. Spaulding, Jr., “Effects of Surface Mining on Fish and Wildlife in Appalachia,” Special Report, Division of Fishery Services, Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife, U.S. Department of the Interior, June 8, 1968.

David V. Hawpe, “Massive Earth Slide Cuts Off 19 Homes; Below Mining Site,” Louisville Courier-Journal (KY), February 18, 1970.

Editorial, “Who Pays For The Damage of Mining?,” Louisville Courier-Journal (KY), February 19, 1970.

David Ross Stevens, “Conservationists Stage Anti-Strip Mining Rally,” Louisville Courier-Journal (KY), March 10, 1970.

David Ross Stevens, “Knott Court Calls Strip Mining Public Nuisance,” Louisville Courier-Journal (KY), May 3, 1970.

Kyle Vance, “Knott County Outlaws Strip Mining As Test of Its Regulatory Powers,” Louisville Courier-Journal (KY), June 7, 1970, p. 1.

David V. Hawpe, “Local Pressure Mounts for Controls on Strip Mining, Heavy Coal Trucks,” Louisville Courier-Journal (KY), June 8, 1970.

David Ross Stevens, “Knott County Magistrates to Decide If County Can Outlaw Strip Mining,” Louisville Courier-Journal (KY), June 8, 1970.

David V. Hawpe, “Leslie County to Use Zoning, Planning to Control Strip Mines,” Louisville Courier-Journal (KY), June 14, 1970.

David Ross Stevens, “Company Fined for Strip Mining Without Permit,” Louisville Courier-Journal (KY), June 27, 1970.

Ben A. Franklin, “Strip-Mining Boom Leaves Wasteland in Its Wake,” New York Times, December 15, 1970.

Ben A. Franklin, “Rockefeller 4th Will Seek State Ban on Strip Mines,” New York Times, December 31, 1970, p. 16.

George Vecsey, “Eastern Kentucky Scarred by Strip Mining, Looks to T.V.A. Suit,” New York Times, March 7, 1971, p. 36.

Ben A. Franklin, “West Virginia Senate Votes Ban On Strip Mining in 36 Counties,” New York Times, March 7, 1971, p. 36.

Peter Harnik, “In Congress: Conservation Versus King Coal,” Environmental Action, March 6, 1971.

“The Strip Mine Problem,” Washington Post, March 18, 1971.

“Strip Mining on Trial,” Washington Evening Star, March 20, 1971.

Peter Bernstein, “Ripping Off Mountaintops in Coal-Rich Appalachia,” Washington Star, March 21 , 1971.

Ward Sinclair, “Strip-Mine Control Is Up to Congress,” Louisville Courier-Journal & Times, (KY), March 1971.

Ward Sinclair, “House Bill Would Forbid All Strip-Mining in United States,” Louisville Courier-Journal & Times, March 1971.

Ward Sinclair, “Gathering Storm: Federal Strip Mining Curbs Stir Hot Response, Pro and Con,” Louisville Courier-Journal & Times, March 22, 1971.

Ben A. Franklin, “Strip Mining Foes Gaining Converts,” New York Times, April 25, 1971.

Ben A. Franklin (New York Times news service), “Bill To Outlaw Strip Mining Gaining Support in Congress,” Arizona Daily Star (Tucson, AZ), April 25, 1971, p. 21.

Homer Bigart, “West Virginia Conserva-tionists Challenging Strip Miners,” New York Times, June 21, 1971, p. 33.

“Peeling Back the Land for Coal,” Newsweek, June 28, 1971, p. 69.

“Congressman-Crusader Gets Tough With Strip Miners,” Kentucky Post, July 13, 1971.

Ben A. Franklin, “Congress Moves to Control Strip Mining,” New York Times, September 19, 1971, p. 64.

William Greenburg, “Some Blame TVA: Strip Mined Poor Look for Villain,” Nashville Tennessean, September 19, 1971.

U. S. Bureau of Reclamation, North Central Power Study; Report of Phase I, 1971.

Ben A. Franklin, “Strip-Mining Foe in Hearing Clash; Chairman of House Panel Is Angered by Militant,” New York Times, October 27, 1971, p. 11.

Ben A. Franklin, “Strip Mine Curb Gaining Support,” New York Times, November. 17, 1971, p. 94.

George Vecsey, “Opponents Move to Curb Appalachia Strip Mining,” New York Times, November 27, 1971, p. 25.

James Branscome, “Appalachia – Like The Flayed Back of A Man,” New York Times Magazine, December 12, 1971.

Peter Borrelli, Richard Cartwright Austin, The Strip Mining of America, 1971, Cornell University, 109 pp.

Ward Sinclair, “Coal’s Congressmen,” The New Republic, January 15, 1972.

“The Way We Were: January 27, 1972,” The Mountain Eagle, January 25, 2012.

Ben A. Franklin, “Ecologists Make Strip-Mine Study,” New York Times, January 30, 1972, p. 59.

Editorial, “Semi-Strip Mining,” New York Times, August 6, 1972.

George Vecsey, “House Unit Maps Strip-Mining Bill; One Coal Group Welcomes Regu-lation Proposals,” New York Times, August 13, 1972, p. 101.

Anthony Ripley, “Strip Mining Bill Dying in Congress,” New York Times, September 27, 1972, p, 18.

*Ben Franklin, “What Price Coal?,” New York Times Magazine, September 29, 1972, pp. 26, 96.

John Walsh, “West Virginia: Strip Mining Issue in Moore-Rockefeller Race,” Science, November 3, 1972, pp. 484-486.

Thomas A. Larsen, “Federal Regulation of Strip Mining,” Boston College Environmental Affairs Law Review, Volume 2, Issue 3, December 1, 1972.

Congressional Quarterly, “Bills Regulating Strip Mining Die in Senate,” CQ Almanac 1972, Washington, DC, 1973.

John P. Stacks, Stripping — The Surface Mining of America, Sierra Club Books, 1972.

Calvin Kentfield, “New Showdown in the West: ‘We Want That Coal Under Your Soil’…,” New York Times Magazine, January 28, 1973, pp. 12, 30-33.

“Nixon Aides Said to Draft Weaker Strip-Mining Bill,” New York Times, February 15, 1973, p. 1.

Ben A. Franklin, “Revisions in Strip-Mining Bill Appear to Aid Industry,” New York Times, February 18, 1973, p. 73.

Howard K. Smith (anchor), Bill Zimmerman (reporter), “Strip Mining,” ABC Evening News, Tuesday, March 13, 1973.

Hearings Before The Subcommittee on The Environment and Subcommittee on Mine & Mining, House Interior and Insular Affairs Committee, 93rd Congress, 1st Session, on H.R. 3 and [14] Related Bills on the Regulation of Surface Mining, April & May 1973.

Vincent P. Cardi, “Strip Mining and the 1971 West Virginia Surface Mining and Recla-mation Act,” West Virginia Law Review, Vol. 75, Issue 4, June 1973.

Alvin Josephy, “Agony of the Northern Plains,” Audubon, July 1, 1973 (impact of the North Central Power Study on the northern plains).

“The New Energy Barons: How Big Oil Controls the Coal Industry,” United Mine Workers Journal, July 15–31, 1973, p. 5.

Associated Press, “A Strip Mine Bill Gains in Senate,” New York Times, September 11, 1973, p. 40.

Richard L. Madden, “Senate, 82-8, Votes Tight U.S. Control Over Strip Mining,” New York Times, October 10, 1973, p. 1.

“Strip Mining,” CQ Reseacher / CQpress.com, November 14, 1973.

Congressional Quarterly, “Senate Passes Strip Mining Bill; House Fails to Act,” CQ Almanac 1973, Washington, DC.

“Coal Experts Say Output Could Be Doubled by 1980,” New York Times, January 6, 1974, p. 52.

Douglas E. Kneeland, “To Ranch in West Or Strip for Coal: A Difficult Choice,” New York Times, February 18, 1974, p. 27.

Laney Hicks, Northern Plains Representative, Sierra Club, “The Future of Energy Devel-opment in Western States,” Energy Conference, North Dakota Academy of Science, April 25-27, 1974.

Gov. Milton Schapp, (Pennsylvania), Letter to the Editor, “Strip Mining: Toward a Strict but Practical Law,” New York Times, May 2, 1974

James P. Sterba, “Reclamation Plan for Strip-Mined Land Stirs Debate,” New York Times, July 3, 1974, p. 39.

Luther J. Carter, “Strip Mining: Congress Moves Toward ‘Tough’ Regulation,” Science, August 9, 1974, pp. 513-514.

EPA, Environmental Protection in Surface Mining of Coal, October 1974.

John L. McCormick, “Facts About Coal,” Environmental Policy Center, Washington, D.C., 1974.

Norman R. Williams, “Displacement of Appalachian Coal by Western Coal,” Memo to Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, U.S. House of Representatives, 1974.

Ben A. Franklin, “Strip Mine Curbs Voted In House in Face of Veto,” New York Times, December 14, 1974, p. 61.

Ben A. Franklin, “Senate Sends Strip Mine Bill to Ford; Prompt Action on Veto Threat Urged; Morton Urged to Act,” New York Times, December 17, 1974.

David H. Anderson, “Strip Mining on Reservation Lands: Protecting the Environ-ment and the Rights of Indian Allotment Owners,” 35 Montana Law Review, 1974.

Luther J. Carter, “Strip Mining: A Practical Test for President Ford,” Science, December 27, 1974.

John Herbers, “President Vetoes Strip Mining Bill, Oil Tanker Plan,” New York Times, December 31, 1974, p. 1.

“Congressional- Strip Mining (2),” Ford LibraryMuseum.gov (White House staff memos, statements and documents, 1974-75).

Congressional Quarterly, “Strip Mining Bill Pocket Vetoed,” CQ Almanac 1974, Washing-ton, DC, 1975.

Ben A. Franklin, “A New Strip Mining Bill Is Forthcoming, Udall Says,” New York Times, January 2, 1975, p. 14.

Ben A. Franklin, “Strip Mine Curbs Voted by Senate,” New York Times, March 13, 1975, p. 1.

Ben A. Franklin, “Coal Strip Mining in the West Facing Obstacles,” New York Times, March 24, 1975, p. 20.

UPI, “Va. Coal Miners Ask Ford to Veto Strip Mine Bill,” Suffolk News-Herald, March 27, 1975.

Associated Press (Big Stone Gap, VA), “Coal Operators Protesting Strip Mining Legisla-tion,” The Messenger (Madisonville, KY), April 1, 1975, p. 7.

Associated Press, “Businessmen and Mine Protest,” The Bee (Danville, VA), April 4, 1975.

“Strip Mine Control Law Sparks Protest of Area Workers Here,” Raleigh Register (Ral-eigh, WV), April 7, 1975.

UPI, “Truckers Cheered on Protest Road,” The Hopewell News (Hopewell, VA), April 8, 1975, p. 2.

Ben A. Franklin, “Strip Mine Group to Protest in Capital,” New York Times, April 8, 1975, p. 73.

“Strip Mine Law Protest,” Evening Herald (Pottsville, PA), April 8, 1975, p. 1, w/ photo.

Ben A. Franklin, “Strip Mine Workers Protest in Capital,” New York Times, April 9, 1975.

“Miles and Miles of Trucks Converge on Washington,” Clinch Valley Times (St. Paul, VA), April 10, 1975, p. 1.

Ward Sinclair, “Mining-Law Protesters [coal truck caravan] Were Misinformed About Provisions,” Louisville Courier Journal, April 11, 1975.

Ernest B. Furgurson, “Miners’ Protest Gulled the Supposedly Skeptical,” Washington Eve-ning Star, April16, 1975.

Ben A. Franklin, “Conferees Adopt Strip-Mine Bill That Both Sides Term Weak,” New York Times, April 30, 1975, p. 14.

Associated Press, “Senate Approves Strip Mining Bill,” New York Times, May 6, 1975, p. 26.

Ben A. Franklin, “Ford Will Repeat Strip Mining Veto,” New York Times, May 20, 1975, p. 1.

Gerald R. Ford (President of the United State, 1974-1977), “Veto of a Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Bill,” Senate.gov, May 20, 1975.

Ben A. Franklin, “Strip Mining Measure Vetoed; House Override Bid Due Today,” New York Times, May 21, 1975.

Editorial, “Strip Mine Veto,” New York Times, May 21, 1975, p. 42.

Ben A. Franklin, “Democrats Plan Strip Mine Drive,” New York Times, May 25, 1975, p. 27.

Rowland Evans and Robert Novak, “Strip Mining, Energy and Politics,” Washington Post, May 30, 1975.

Walter Taylor, “50 Defectors Needed for Mining Bill,” Washington Star, June 4, 1975.

Ben A. Franklin, “Foes of Strip Mine Veto Wring Data Concessions,” New York Times, June 4, 1975, p. 20.

Tom Raum, Associated Press, “Opponents Of Strip Mine Veto Vow To Try Once More,” Lewiston Evening Journal (Lewiston-Auburn, ME), June 10, 1975, p. 11.

Ben A. Franklin, “Strip Mine Bill Veto Is Upheld by House On a 3-Vote Margin,” New York Times, June 11, 1975, p. 1.

Ward Sinclair, “Contradictions, Discrepancies Noted – Data Used to Justify Strip-Mine Bill Veto Questioned,” Louisville Courier-Journal (Louisville, KY), June 30, 1975.

Stephen E. Nordlinger, “Coal-Veto Data Held Sloppy,” Baltimore Sun, June 30, 1975.

“The Energy Information Act,” Hearings Before the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, U.S. Senate…, 1974 (Sinclair & Nord-linger, p. 147).

“Evaluation of the Analysis Supporting President Ford’s Veto of H.R. 25, the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1975,” GAO.gov, April 15, 1977.

Editorial, “Strip ‘Mining and Coal Leasing,” Washington Post, October 22, 1975.

Louise C. Dunlap, “An Analysis of the Legisla-tive History of the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1975,” Proceedings of 21st Annual Rocky Mountain Mineral Law Institute, August 1975.

Mike Jacobs, One Time Harvest: Reflections on Coal and Our Future, 1975, Indiana University, 300 pp. (originally published by the North Dakota Farmers Union).

Ben A. Franklin, “House Democrats Renew Drive for Strip-Mine Bill,” New York Times, August 26, 1976, p. 36.

John C. Doyle, Jr., Strip Mining in the Corn Belt. The Destruction of High Capability Agricultural Land for Strip-Minable Coal in Illinois, 1976, Environmental Policy Institute, Washington, DC.

Hon. Patsy Mink, “Reclamation and Rollcalls: The Political Struggle over Stripmining,” Environmental Policy and Law, 1976, Elsevier Science Publishers, pp. 176–180.

Richard Cartwright Austin, Spoil: A Moral Study of Strip Mining for Coal, National Division, Board of Global Ministries, United Methodist Church, 120 pp., 1976.

Mary Russell, “Urgent Coal Demand vs. Strip-Mine Curbs,” Washington Post, February 15, 1977.

Hon. Morris K. Udall, “The Enactment of the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977 in Retrospect,” West Virginia Law Review, 1979, Vol 81, No. 4.

Edward Shawn Grandis, “The Federal Strip Mining Act: Environmental Protection Comes to the Coalfields of Virginia,” University of Richmond Law Review, 1979, Volume 13, Issue 3, Article 3.

Louise C. Dunlap and James S. Lyon, “Effectiveness of the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act: Reclamation or Regula-tory Subversion?,” West Virginia Law Re-view, 1985-1986.

Michael Lipske, “Cracking Down on Mining Pollution: Environmental Lawyer Thomas Galloway Develops Applicant/Violator System to Find Violators of Mining Law,” National Wildlife, June-July 1995.

Penny Loeb, “Shear Madness,” U.S. News & World Report, August 11, 1997.

Public Employees for Environmental Respon-sibility (PEER), “Empty Promise: Twenty Years of Failure in Federal Strip Mining Regulation – A Special Anniversary Report by the Employees of the Office of Surface Mining,” August 1997.

Michael Shnayerson, “The Rape of Appa-lachia,” Vanity Fair, May 2006.

Western Organization of Resource Councils (WORC) and Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), “Undermined Promise: Reclamation and Enforcement of the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act,” August 2007.

“Surface Mining Act,” Hearing Before the Committee on Energy and Natural Resources, U.S. Senate, 110th Congress, 1st Session, “To Receive Testimony on the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977: Policy Issues Thirty Years Later,” S. Hrg. 110–298, November 13, 2007 (see, for example, citizen testimony of Cindy Rank).