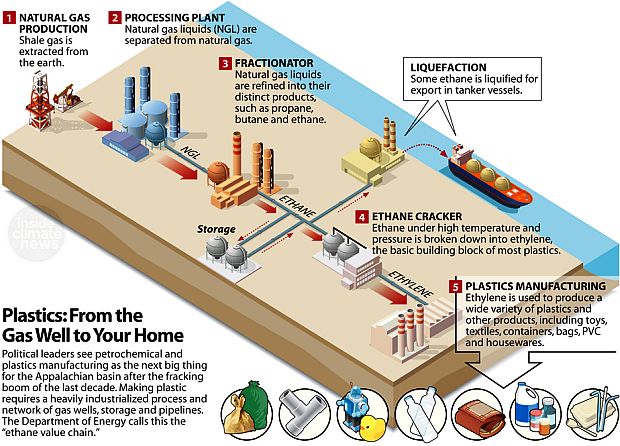

A nurdle is a piece of plastic – a tiny piece, about the size of a lentil. Nurdles are made by petrochemical companies such as Dow, ExxonMobil, Chevron Phillips, Shell and Formosa. They are, in fact, the starting point in the plastics-making process – also known as “pre-production pellets” or “resin.” They can be made of polyethylene, polypropylene, polystyrene, polyvinyl chloride and other plastics. They are often opaque or white, but can also be made in colors. Nurdles are a kind of “synthetic ore,” not mined, but manufactured in petrochemical processes, made from oil and natural gas. They are the beginning ingredients that feed the plastics industrial complex worldwide.

A tiny crab trying to make its way on a Sri Lankan beach polluted in May 2021 with pre-production plastic pellets known as nurdles that washed ashore on miles of coastline from an offshore burning and sinking container ship, the MV X-Press Pearl. Details later below. (Eranga Jayawardena/Associated Press & Washington Post).

Every year, gazillions of nurdles are produced and shipped to factories and fabricators across the U.S. and around the world, where they are melted and poured into molds that churn out water bottles, computer casings, water pipes, steering wheels, and more. But one big problem with nurdles is that when they get loose in the environment, it’s a little like herding cats — and worse. For nurdles are light and buoyant, can be blown by the wind, and often float in water. And yes, they do get loose, and the record so far has not been good.

Nurdles often appear as opaque or white pellets, each the size of a lentil, looking like fish eggs. |

Plastics factory in New Jersey with worker walking amid large containers of blue-colored plastic nurdles. Laura Sullivan/NPR. |

Sri Lankan Spill. In May 2021, one of the largest nurdle spills at sea occurred off Colombo, Sri Lanka, when the container ship, X-Press Pearl caught fire and partially sank near Colombo harbor. Among the ship’s 1,377 containers were 422 holding nurdles, which spilled and dispersed over 300 kilometers (186 miles) of the Sri Lankan coastline. “It’s an environmental disaster,” Sri Lankan marine biologist Asha de Vos told The Washington Post at the time of the spill. She was worried that currents might carry the plastic pellets as far as the other side of the island nation, killing wildlife and damaging sensitive ecosystems. “It was basically [plastic] snow on our beaches,” she explained of the immediate impact, with photos showing piles of the tiny white pellets (some burnt and darkened by the ship’s fire) stretching for miles along the coastline. The incoming nurdles accumulated as much as 2 meters thick (about 2 yards) in some places.

Map of Sri Lanka, off India, showing location where ‘X-Press Pearl’ spilled billions of nurdles. |

Photo showing piles of spilled nurdles along Sri Lankan coast-line in 2021, where attempted clean-up went on for months. |

A dead fish that had washed ashore from the Sri Lankan spill was photographed with a mouth full of nurdles – no doubt, one of many meeting similar fates. It was also reported that some 470 turtles, 46 dolphins, and eight whales that had washed ashore also had nurdles in their bodies. For the local population, some 20,000 families had to stop fishing. About 1,680 tons of nurdles were released into the ocean with the Sri Lankan spill, and some also made landfall across Indian Ocean coastlines, from Indonesia and Malaysia to Somalia. The clean up – at least of those nurdles that could be seen on the beaches – went on for months. Others are buried in the sand, with still others floating or submerged at sea, and for a time following the spill, deposited on shorelines at regular intervals with each incoming tide. The Colombo-based Center for Environmental Justice later estimated that as many as 70 billion nurdles were spilled. As of this writing, it’s the largest plastic spill in history, according to a United Nations report.

The Sri Lankan spill, however, wasn’t the only such incident. In fact, nurdle spills at sea have been occurring for decades, many unreported. Of documented spills in recent years, there have been several releasing large quantities of nurdles.

Volunteer working to clean up plastic nurdles deposited in a rocky coastal area of southern Hong Kong following a major spill of the plastic pellets from a container vessel during a July 2012 typhoon. Tyrone Siu /Reuters.

2012, Hong Kong. A nurdle spill occurred off Hong Kong during a storm on July 24, 2012, when 150 tons of nurdles from shipping containers owned by Chinese oil giant, Sinopec, were released into the sea. During Typhoon Vicente, a container ship lost seven 40-foot containers in the waters south of Hong Kong. Six of the containers contained bags of plastic pellets. The polluting pellets swamped beaches, clogged shore grasses, and piled up along rocky coasts, making for a difficult clean up. In any case, the plastic pellets washed up on a number of southern Hong Kong beaches and islands, among them, Shek O, Cheung Chau, Ma Wan, and Lamma Island.

Because Hong Kong is made up of more than 200 islands it was hard to know how bad the spill actually was.Tracey Read, a local cleanup volunteer at the Hong Kong scene, told Plastics Today: “The initial spill looked like snow on several beaches and in quite a few areas the pellets were knee deep.” Some of the nurdles in that spill are believed to have disrupted marine life in the area, also credited with killing stocks of fish at fish farms. The pellets were also found in the guts of fish and locals became reluctant to eat seafood. Because Hong Kong is made up of more than 200 islands it was hard to know how bad the spill actually was.

According to some reports, the plastic pellets in the Hong Kong spill once covered Sham Wan of Lamma Island, a spawning area for endangered green sea turtles, where tourists are forbidden during the spawning season. The Hong Kong nurdle spill occurred during the turtles’ spawning months and Sham Wan was reportedly covered by a foot of plastic pellets for a time.

Sinopec, meanwhile, initially set aside $1.28 million to help with the clean up. More than a month following the spill, incoming tides bearing nurdles left repeated deposits of pellet lines on beaches. Half a year later, plastic pellets were still found at Ngong Chong Beach on Po Toi Island. And even six years later, mounds of the pellets were still being found on some of the Hong Kong islands.

In 2011-2012, the M.V. Rena cargo ship lost hundreds of containers when it ran aground and later broke apart off the coast of New Zealand. While a fuel oil spill and other toxic cargo were major concerns in this accident, the ship also reportedly lost four containers of plastic nurdles. Nine years later, in 2020, residents were reporting nurdles on local beaches.

2011-2012, New Zealand. In early October 2011, the container vessel M.V. Rena lost an estimated 900 containers of various products and substances when it ran aground and later broke up off the coast of New Zealand after striking Astrolabe Reef 12 nautical miles off Tauranga. While a major spill of fuel oil and the loss of some containers with toxic substances became major concerns in this accident, a reported four of the lost containers held plastic nurdles. Over time, much of the shipwreck’s resulting shoreline debris was cleaned up. However, some nine years later, in 2020, plastic beads were found washing ashore on the Coromandel and Waihi beaches of New Zealand, in the same areas where shipwreck debris had washed up at the time of the initial grounding. Some reporting indicated that at least one container of nurdles – and perhaps as many as four – were lost in the accident or remained missing. Meanwhile, as of June 2021, nearly ten years after the accident, an investigation had been launched into whether plastic beads then washing up on Tairua Beach were from the wreck of the M.V. Rena.

2017 & 2020, South Africa. Nurdle spills have also been reported in the sea lanes along South African shores and port areas over the last several years. In October 2017, a freak hurricane ripped ships from their moorings in the port of Durban, South Africa, causing chaos there. Two vessels belonging to Mediterranean Shipping Company collided and cargo containers holding 49 tons of nurdles went into the sea. Two nurdle-filled containers from the MSC Susanna were among those spilled, remaining submerged for a time in the harbor. Five days after the storm, local residents noticed that millions of plastic nurdles were washing up on beaches. Reports noted that nurdles had moved as far north as the border with Mozambique, and as far south as Cape Town. Between 1,200 km to 2,000 km (roughly, 745-to-1,240 miles) of coastline were polluted with pellets from this spill.

Adapted portion of larger 2018 South African graphic, “What Are Nurdles?,” illustrating 2017 Durban spill and clean-up progress at that time. Source: SA Association for Marine Biological Research, News 24/Rudi Louw.

As reported elsewhere with attempted nurdle coastline clean-ups, South African efforts were frustrated by repeated tidal deposits of the pellets. Meanwhile, by the time the South African authorities began their cleanup attempts, some of the spilled nurdles had already begun making their way to Australia, and were estimated to arrive there about 450 days later. Some nine months after the South Africa clean up had begun, less than 20 percent of the nurdles had been recovered. News videos of the clean-up there illustrate the difficulty of completely removing the pellets even on accessible beaches, let alone those with more rugged terrain, grasses, and other obstacles.

In 2020, another South African nurdle spill occurred off the coast of Plettenburg Bay. That spill was believed to have come from containership CSAV Trancura (photo below), while that vessel was proceeding to Singapore on or about August 21st, 2020. When later docked at Coega, Eastern Cape, South Africa, it was observed that part of the container stack on this ship had collapsed, suggesting that a number of containers may have been lost overboard.

The CSAV Trancura container ship, the suspected source of an August 2020 South African nurdle spill. (Photo: Hans Schaefer / MarineTraffic.com).

2019 & 2020, North Sea. The cargo ship MSC Zoe lost 350 containers to the North Sea in a January 2019 storm, some of which were full of plastic nurdles. More than a year later, millions of the pellets continued to wash up on the beaches of the Dutch Wadden Sea island of Schiermonnikoog. In February 2020, the cargo ship Trans Carrier – transporting nurdles from Rotterdam, Netherlands to a Norwegian plastic pipe manufacturer in Tananger – spilled more than 13 tons of nurdles into the German Bight area of the North Sea, which were then dispersed along the coastlines of Denmark, Sweden and Norway. These nurdles were produced by INEOS, the chemical company in Antwerp that imports U.S. ethane made from shale gas to produce the plastic pellets.

A portion of the millions of plastic nurdles that washed ashore on the coast of Norway, following a February 2020 North Sea spill. These nurdles, from that spill, were photographed at Oslofjord, Norway. Photo, Plastic Soup Foundation.

Nurdle spills are occurring everywhere, it turns out – on land and at sea. It’s likely that nurdles have been on the loose for decades, probably since the start of the modern plastics era.

In 1971, researchers collected plastic pellets in an area of the North Atlantic called the Sargasso Sea by towing fine mesh nets through the water. Fifteen years later, Woods Hole researchers returned to the area and found that pellet concentrations had nearly doubled. Plastic pellets were found on New Zealand beaches in 1977. In 1993, the U.S. EPA reported widespread distribution of nurdles – among the most commonly found items in 13 of 14 U.S. harbors then sampled. There have also been a variety of nurdle spills in the U.S., some inland at transport and factory locations, and others from spills and releases into creeks, streams, rivers, estuaries and bays. Some of these are offered later below.

Cover of a 1993 EPA summary document from a more detailed study of plastic pellets in the environment. Click for PDF.

Nurdle losses, leakage, and spills can occur at any point in the plastics-making process. Nurdles that fall on the factory floor or on the ground at loading docks and transportation hubs, are considered contaminated and are thrown out or washed into sewer drains. Nurdles are shipped extensively by rail and truck on land, by river barges, and handled or re-packaged at ports for international shipping for export by container vessel – and they can and do spill at all of these junctures, fouling streams, rivers, bays, and the oceans. Due to their small size and buoyancy, pellets lost on land often find their way to various water bodies through runoff. In 2005, one study of 10 facilities that handled pellets in California found that during heavy rainstorms pellets washed away from every single facility. In Sweden, at one production facility, it was estimated that between 3 million and 36 million pellets entered the environment each year. There is no standardized reporting of such spillage, however, and no real regulation.

As for shipment on the high seas, there have been attempts in Europe, but little progress to date, to tighten international maritime and shipping standards for handling and packaging nurdles. Since 1991, petrochem producers have pushed a voluntary program called “Operation Clean Sweep,” aimed at implementing good housekeeping and pellet containment practices, with the goal of achieving “zero pellet, flake, and powder discharge.” But not all producers are engaged in the voluntary program. In fact, by one count of plastic handlers and producers in Europe as of October 2020, of 60,000 facilities, only 500 were then pledged to Operation Clean Sweep. Nor does “pledging” mean zero discharge.

In many cases of nurdle spills in the U.S., clean-ups and/or prosecutions are not triggered by environmental laws since nurdles are not, by themselves, toxic or hazardous. However, in a few recent cases, as will be shown later below, the U.S. Clean Water Act has been used both in regulation and litigation to bring some accountability to nurdle polluters. In 2022, legislation was introduced the U. S. Congress under the title, “The Plastic Pellets Free Waters Act,” that would direct EPA to bar the discharge of plastic pellets into waterways, storm drains or sewers from any point source “that makes, uses, packages, or transports those plastic pellets and other pre-production plastic materials.” As of this writing, however, the House and Senate bills have made little progress.

Adapted portion of larger 2018 South African graphic, “What Are Nurdles?” Source: SA Association for Marine Biological Research, News 24 / Rudi Louw.

Most problematic – especially for birds, fish, marine mammals and food chains to humans — is the fact that nurdles can absorb a range of toxic chemicals already in the environment, including long-banned substances such as PCBs and DDT that are still out there. In its 1993 report, “Plastic Pellets in the Aquatic Environment,” EPA listed about 80 species of shorebirds that were known at that time to be eating nurdles, as well as sea turtles, fish, and potentially baleen whales. And with time in the environment, the already tiny nurdles can weather and break down into even smaller microplastics, enduring for decades.

The nurdle problem so far has received its most extensive exposure and documentation from citizen action in Europe and the United States (with related media coverage) – activism that has spread throughout the world. In Europe, FIDRA, an NGO based in East Lothian, Scotland that works to reduce plastic waste and chemical pollution, has led citizen groups throughout the world to track the nurdle problem, sponsoring an annual nurdle count and reporting “hot spots” and updates at its website. In the U.S., a Texas scientist, Jace Tunnell, Director of the Mission Aransas National Estuarine Research Reserve, founded “The Nurdle Patrol” in 2019 which has spurred voluntary citizen counts, nurdle spill reporting, and data collection throughout the U.S. and beyond. There has also been some litigation in the U.S. in recent years – including one case in Texas brought by long-time activist, Diane Wilson and others, resulting in a $50 million verdict against Formosa Plastics for its nurdle pollution. More detail on these and other stories follow below.

May 26, 2022

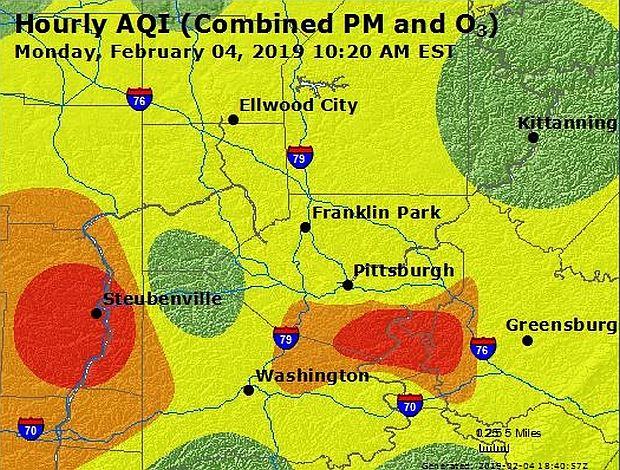

Pittsburgh Train Spill

A Norfolk Southern train derailment just north of Pittsburgh, PA on May 26, 2022, in addition to sending 3,000 gallons of petroleum distillates spilling into Guy’s Run creek and the Allegheny River, also spilled plastic nurdles into those waters. Some17 train cars and two engines derailed after a collision with a dump truck carrying stone. Nine of the rail cars were reported to have gone down an embankment there, some lading in the Guy’s Run creek, not far from its juncture with the Allegheny River. One or more of the rail cars carried plastic pellets. It was reported that some unstated quantity of pellets escaped the rail cars, and were seen in the creek. Booms were deployed on the creek in attempt to prevent the pellets from reaching the river. Later citizen reporting in early June 2022, along with photos from Three Rivers Waterkeeper, indicated that “millions of nurdles” from this spill did make their way into Guy’s Run and likely, the Allegheny River as well. Some quantity of the pellets were cleaned up and hauled away, but others were released into the environment. North of Pittsburgh, meanwhile, a new Shell Oil plastics complex will soon be turning out billions of nurdles every year, shipping them all across the country and beyond.

Screenshot from KDKA-TV report, showing aerial view of May 2022 train derailment just north of Pittsburgh, with several rail cars in Guy’s Run creek near its junction with the Allegheny River. The “white-ish color” visible in the creek is actually millions of floating plastic nurdles – some of which were cleaned up, bagged, and hauled away.

Train spills of nurdles, it turns out, occur with some frequency, as do more “routine” spills and operational accidents at rail yards. Nurdles are shipped by rail in hopper cars throughout North America. A single car can contain millions of these microplastics. One report online of U.S. rail-related nurdle spills using National Response Center reporting has noted more than 80 such incidents in at least two dozen states since 2010. Jace Tunnel, founder of The Nurdle Patrol, has conducted surveys at over 80 railroads across the United States and found nurdle releases at over 90 percent of them. A few examples of other reported train spills follow.

Iowa. In November 2021, a Union Pacific train in Iowa derailed about one mile east of Carlisle, Iowa. The accident occurred where the railroad crosses the Middle River. One of the rail cars went down the riverbank and leaked polyethylene pellets into the river, which is a tributary of the Des Moines River. Union Pacific put a boom in the river attempting to prevent the pellets from moving downstream, though some pellets got through. A few days later, another boom was placed in the river attempting to catch more of the pellets.

Septembr 4, 2021 This aerial photo, which appeared online, shows the derailment of four cars near Raceland, Louisiana with some spillage of plastic pellets, seen in white, some of which may have infiltrated nearby canal/waterway that is possibly connected to the Lake Boeuf Wildlife Management Area.

Louisiana. A derailment of four train cars near Raceland, Louisiana occurred on September 4th, 2021 with some spillage of plastic pellets, according to National Response Center (NRC) reporting and aerial photographs. The release of plastic by the NRC is considered a “railroad non-release,” but still recorded. At this accident scene, there appears to be a canal or waterway near the spillage that is possibly connected to the Lake Boeuf Wildlife Management Area.

Texas. In January 2021, two trains collided in Jackson County, Texas – one operated by Formosa Plastics Corp. and one Union Pacific – resulting in spill of diesel fuel, oils, and plastic pellets. It was reported that a couple of the cars were laying on local roadways, which were closed for a time. No injuries were reported and clean-up teams were sent to the site.

April 25th, 2013. Derailment at Wheeling & Lake Erie Railroad’s Gambrinus Yard in Canton, Ohio. caused three hopper rail cars to spill plastic pellets in a train yard. Photo shows two of the cars on their side with visible spills of white pellets.

Ohio. A train derailment on April 25th, 2013 caused three hopper rail cars to spill plastic pellets in a train yard at the Wheeling & Lake Erie Railroad’s Gambrinus Yard in Canton, Ohio. Photos showed two of the cars on their side with visible spills of pellets. The cause of the mishap was not specified and clean-up crews were sent to the site. According to the company’s website: “The Wheeling & Lake Erie Railway Company handles thousands of carloads of chemicals, plastic resins, and related products every year for 25+ shippers and receivers. Northeast Ohio in particular is a frequent destination for many polymer shipments for molding companies, blenders, packagers and transload operations. Shipments in covered hoppers include ABS plastics, polyethylene, polypropylene, polystyrene, and polyvinyl chloride.”

Texas. Nurdles were spilled at the site of a Union Pacific derailment near Algoa, Texas in August 2009, when twelve of the train’s 80 cars left the tracks, some spilling the plastic pellets there, entailing a local cleanup.

![Chuck Hutterli of Nipigon, Ontario (shown at left) has been cleaning up recurring tidal deposits of white nurdle pellets off the Lake Superior beach near his home for more than a decade, not far from where a 2008 Canadian Pacific train derailment spilled them into Lake Superior. “Yep, they’re still coming,” said Hutterli in 2021 of the nurdle beach deposits [especially after windstorms]. “It’s aggravating as hell.” (Courtesy photo / MLive.com)](https://149777103.v2.pressablecdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Great-Lakes-RR-spill-620.jpg)

Chuck Hutterli of Nipigon, Ontario (shown at left) has been cleaning up recurring tidal deposits of white nurdle pellets off the Lake Superior beach near his home for more than a decade, not far from where a 2008 Canadian Pacific train derailment spilled them into Lake Superior. “Yep, they’re still coming,” said Hutterli in 2021 of the nurdle beach deposits [especially after windstorms]. “It’s aggravating as hell.” (Courtesy photo / MLive.com)

Ontario, Lake Superior. On January 21, 2008, a Canadian Pacific train was traveling along Lake Superior in Southern Ontario. As the train passed through Cavers Cove, near Rossport, fourteen cars derailed, including four filled with polyethylene pellets, which reportedly plunged into deep water off a nearshore cliff. The plastic pellets were swept into Lake Superior and carried along by wind, waves and currents. Canadian Pacific cleaned up some of the spill in February of 2008 and in several subsequent cleanups, and reported spending over a million dollars in the process. However, a significant portion of the nurdles were already taken up by the lake immediately following the spill and remain heavily concentrated near the site of the spill, and have also dispersed across much of eastern Lake Superior. For more than decade now, some of the nurdles from this spill continue to appear on Lake Superior beaches in Canada and the United States.

August 2, 2020

Mississippi River Spill

On August 2nd, 2020, as sudden winds rose on the Mississippi River, four shipping containers were knocked off the container ship, Bianca, then docked at the Napoleon Avenue wharf at the Port of New Orleans. Three of the containers were retrieved. But the fourth container, containing numerous 55-pound bags of Dow Chemical polyethylene nurdles, fell into the Mississippi River. The container with the Dow bags was retrieved from the river a few days later, but an undetermined number of nurdles – likely, tens of millions or more – were released into the environment. CMA CGM , the shipping company for the Bianca, briefly started a clean-up three weeks after the spill that was halted due to storm threats. In the meantime, spilled nurdles were pushed upstream and downstream, and in subsequent weeks, were evident in deposits along both banks of the Mississippi as well as further south into the Delta, and likely, the Gulf of Mexico and beyond.

August 2020. Nurdle deposits along New Orleans waterfront following spill on Mississippi River. Photo, Liz Marchio, NOLA.com. |

August 2020. A 55 lb bag of Dow Chemical polyethylene nurdles beneath New Orleans wharf following spill. Photo, Julie Dermansky for DeSmog.com. |

Following the Mississippi River nurdle spill, Mark Benfield, a professor at LSU, along with Dr. Liz Marchio, a local scientist, became involved in documenting the spill and collecting samples. Benfield estimated that each 55-pound Dow Chemical sack contains roughly 753,000 nurdles. A forty-foot long shipping container, like the one that fell into the river, could hold more than 745 million nurdles. One bag of Dow polyethylene nurdles, as shown above and below, was found beneath a wharf in the New Orleans French Quarter.

Close-up photo of a portion of a bag of Dow polyethylene nurdles that was found beneath a wharf in the French Quarter of the Port of New Orleans following a container spill on the Mississippi River in August 2020.

“Some of the chemical compounds used to make the nurdles could be soluble in the river water,” according to Wilma Subra, technical advisor for the Louisiana Environmental Action Network. After reviewing the contents listed by Dow Chemical, she explained: “The polymerized material can be eaten by fish and birds, cause damage to aquatic organisms that can be eaten by other organisms, including humans. Residual chemicals can end up in the water that the water treatment system doesn’t remove.” Downstream residents, then, whose water begins with Mississippi River intakes, might be at risk.

Mark Benfield of LSU holds partially-damaged bag of Dow Chemical nurdles spilled from container ship into the Mississippi River during August 2020 storm that struck docked ship in New Orleans. The bag was retrieved from a wharf area following the spill. He and associates are helping to document nurdle spills. Photo, Neel Dhanesha/Vox.

Benfield, at one point, described the Mississippi River mess as “a nurdle apocalypse” — a term appropriate for the larger world-wide assault that’s been going on as well. He has also expressed the injustice of such spills. “If I went to the river and tossed in hundreds of plastic bags, I’d be in trouble,” Benfield noted in an interview with Vox.com. Under Louisiana law, he might be fined between $500 and $1,000 for the offense, plus serving a few hours in a litter abatement program. “But because (the nurdles) are so small,” he continued, “the companies get away with it.”

2019-2021

Port of Charleston

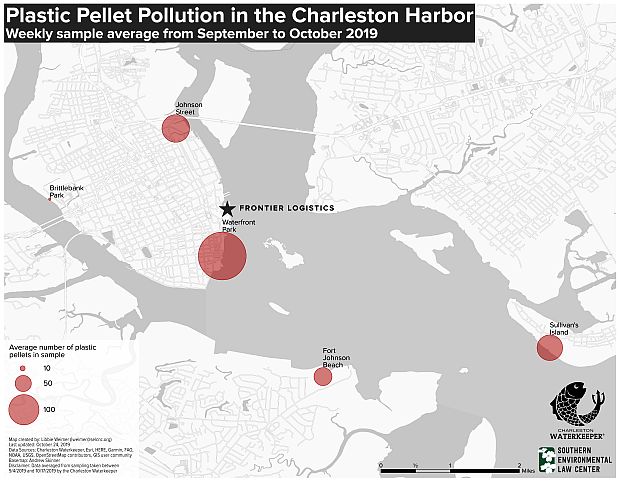

In July 2019, Charleston, South Carolina environmental lawyer, Andrew Wunderley, also executive director of the Charleston Waterkeeper and the Coastal Conservation League, was alerted by some beachcombers of small plastic particles on Sullivan’s Island, South Carolina, a 2.5 mile-long barrier island along the Atlantic coast just off Charleston Harbor. Wunderley and others soon discovered extensive nurdle pollution there and other onshore areas and marshes around Charleston Harbor. After the South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control investigated the nurdle pollution, but took no action, the Southern Environmental Law Center (SELC) filed a federal lawsuit in March 2020 under the Clean Water Act on behalf of the Charleston Waterkeeper and the Coastal Conservation League.

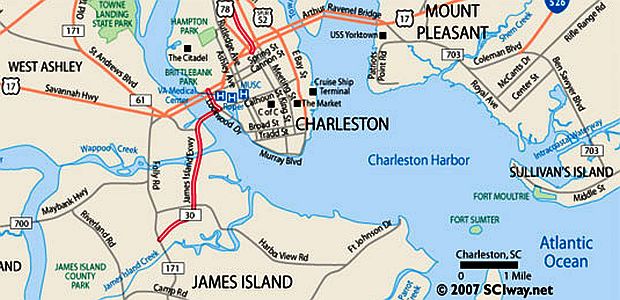

General reference map showing the location of Charleston, South Carolina, Charleston Harbor, Sullivan’s Island and the Atlantic Ocean.

The target of the lawsuit was a shipping company, Frontier Logistics, then operating a plastic pellet packaging facility at Union Pier in downtown Charleston, believed to be the suspected source of the at least some of the nurdles found on Sullivan’s Island and around Charleston Harbor. The company received quantities of plastic nurdles by rail from Gulf Coast petrochemical companies and re-packaged them for export from the Port of Charleston.

Meanwhile, Andrew Wunderley and others had combed beaches and slogged through marshes for months on Sullivan’s Island and around Charleston Harbor to meticulously document the nurdle pollution.

Audubon magazine photo of Charleston Waterkeeper, Andrew Wunderly, who along with Cheryl Carmack, have collected, documented, and archived nurdles they have found in the Charleston area. Photo, Justin Cook / Audubon Magazine, Summer 2020.

“We have evidence that leads us to believe Frontier’s plastic pellets continue to spill into our harbor,” Wunderley told the Charleston Post and Courier at one point. “We find pellets everywhere we look, from Capers Island to Waterfront Park downtown. And, at the sites we sample week after week, we continue to find consistently high numbers of pellets.”

In March 2021, Frontier agreed to pay $1.2 million to settle the lawsuit. Separately, the company had also moved to a new, larger facility in North Charleston. Frontier also agreed to allow an independent auditor, accompanied by a nurdle-pollution expert, to visit its new facility to make recommendations on preventing the plastic pellets from getting into the environment.

Map showing some of the locations where Andrew Wunderley and others had combed beaches and marshes in the Charleston Harbor area documenting nurdle pollution. Source: SC Waterkeeper & SELC.

Charleston, it turns out, has several companies that offer nurdle packaging and shipping services for the plastics industry, which in recent years has grown, given the port of Charleston’s increasing appeal for export shipping. A new company in the area, A&R Logistics, located just north of Charleston along Highway 52, opened in September 2020. Two huge warehouses there take trainloads of incoming plastic pellets and then packages them for export to foreign countries through the Port of Charleston.

New A&R Logistics warehouse, located just north of Charleston, SC, opened in September 2020. The company bags plastic pellets shipped to it in volume by rail to prepare them for export to foreign markets through the Port of Charleston. Photo provided to PostandCourier.com / A&R Logistics

In recent years, according to the South Carolina Ports Authority, Charleston has been moving to increase its share of plastic resin exports, expecting to grow from about 800 forty-foot shipping containers per month to more than 2,000 containers per month. Charleston’s primary market for the plastic pellet shipments is Europe, followed by Latin America and Southeast Asia via Suez Canal.

Photo of shipping container cranes and equipment at the Port of Charleston, South Carolina.

April 2018

Pennsylvania Truck Spill

In early April 2018, thousands of pounds of nurdles wound up in a stream in Northeast Pennsylvania near Tannersville after a semi-truck carrying them crashed along a highway. Some 50,000 pounds of blue-colored, recycled plastic pellets were in transit in the truck then traveling in Monroe County, Pennsylvania. According to a state police report, the truck driver had swerved to avoid slowed traffic as he drove along Interstate 80, and then collided with a minivan, causing a chain-reaction crash. The truck then swerved again, going through a guardrail and down a steep embankment. The truck fell 250 feet down the embankment, turned over on its side, and then dumped between 25,000 and 27,000 pounds of the plastic pellets into Sand Spring Run, according to Eric Weredyk, a Pennsylvania conservation officer in charge of the response. The pellets, he told The Morning Call newspaper of Allentown, PA, “were pouring out the back of the truck like water.”

April 2018. View of plastic pellets spilled into creek in Monroe County, PA after a truck crash on I-80. The spilled pellets, shown here in a snowy creek scene, soon floated downstream from Sand Spring Run crash site to Pocono Creek more than three miles downstream. Photo, Morning Call newspaper and Bob Heil, Broadhead Water Association.

Not only were the pellets in Sand Spring Run, at the crash site, but soon made their way downstream to Pocono Creek. Eventually, if not corralled, they would reach the Delaware River, Delaware Bay, and the Atlantic Ocean. As noted in The Morning Call news account of the spill, “cleaning them up won’t be easy — the pieces are small, the water is fast and the crash site is hard to reach.” A few weeks later, along Pocono Creek, citizen volunteers were being sought by conservation groups to help clean up the pellets.

Photo from LehighValleyLive.com shows Todd Burns, president of the Brodhead Chapter of Trout Unlimited, examining trapped plastic pellets on April 6, 2018, along Pocono Creek, washed downstream from the earlier truck spill.

2019, Canada

Vancouver Island Nurdles

In October 2019, the Surfrider Foundation of Canada reported that after a three-year study it had found that thousands of plastic pellets – linked to Vancouver, British Columbia plastic manufacturers – were getting into storm drains which then flowed into the Fraser River and Salish Sea. The organization said its investigation found hundreds of thousands of the pellets clustered around a dozen metro Vancouver plastic industry sites – which the group called, “a widespread problem that must be addressed by both industry and the province.” The Surfrider’s study suggested the nurdles had made it as far as the west coast of Vancouver Island, with high concentrations of the pellets reported on the Sunshine Coast, Gulf Islands and Fraser estuary. In February 2020, the Surfriders were asking the government to take action on the problem. Amine Korch, chair of the Vancouver chapter of Surfrider noted, “…We have reports of people fishing in the Fraser River and the salmon that they find… [have] a bunch of pellets inside.”

This map shows Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada, just off the Northwest corner of the United States north of Seattle, WA. It is a screen shot from a 2019 Canadian television news report on nurdle pollution in the waters off and around Vancouver city, BC, the Fraser River, Salish Sea, and Vancouver Island. Source, Global News, Canada.

2009-2017

California Plastics Plants

In California, state and federal regulators have been active in some parts of the state with inspections and enforcement action at various plastics production companies, where they have discovered nurdle spills and/or poor containment practices, citing violations, imposing fines, and issuing abatement orders. As of January 2008, California Assembly Bill 258, became law and is now part of the California Water Code, known as the “Preproduction Plastic Debris Program.” It applies to all California facilities that manufacture, handle or transport preproduction plastic, including manufacturers, transporters, warehousers, processors, and recyclers.

In the San Francisco Bay area, surprise inspections during October 2009 at four plastic manufacturers resulted in the discovery of nurdle discharges at those facilities, often at rail unloading sites and other plant locations. Some of the nurdle pollution ended up in endangered species habitat at Oyster Bay, on the eastern end of San Francisco Bay. Notices of the violations were sent out to the companies, some with attached photos of nurdle spills at those facilities.

Photo of nurdles on the ground at rail docking area of Metro Poly Corp of San Leandro, CA. One of more than a dozen photos of nurdle spills taken by the San Francisco Bay Area Water Board at Metro Poly during 2009-2010 inspections. Metro Poly later complied with abatement order adding multiple containment improvements.

A cleanup and abatement order involving several of the charged companies was also issued by the San Francisco Bay Regional Water Board for the Oyster Bay Regional Shoreline park in San Leandro, located along the eastern shore of San Francisco Bay. And by October 2011, the State Water Board, San Francisco Regional Water Quality Control Board, and the U.S. EPA collaborated on a joint enforcement action that required multiple industrial plastic businesses to carry out an environmental clean-up of pre-production plastics discharged into Oyster Bay Regional Shoreline in San Leandro. That action required the responsible parties to cleanup and abate their production sites, surrounding wetlands, and related waterways where pellets were being discharged. The Oyster Bay cleanup was paid for by the four companies responsible for the plastic discharges.

EPA inspections and enforcement actions for nurdle releases have also occurred in Southern California. In December 2015, EPA found violations at two plastics facilities releasing pellets through storm drains that discharge to the Tujunga Wash, which flows into the Los Angeles River. Cleanup orders and fines were issued to Western States Packaging of Pacoima and Direct Pack of Sun Valley.

The visible “white-ish” discharge shown here from storm- water runoff in California, is actually, on closer inspection, a few thousand or so plastic nurdles. Photo, California EPA / State Water Resources Control Board.

Western States Packaging uses nurdles as raw material to manufacture food-grade plastic bags. EPA’s inspectors found this facility was not operating with the proper stormwater permit. EPA found spilled plastic pellets on paved surfaces throughout the facility that lacked proper control measures. Western States agreed to pay a $25,000 penalty. Direct Pack uses nurdles to manufacture plastic packaging products. This facility was discharging industrial wastewater without the proper permit. An inspection found that the facility did not use proper capture devices and did not have containment systems to prevent releases to local waterways, among other deficiencies. Direct Pack’s penalty was $42,900.

“The Los Angeles River provides vital habitat to birds, fish and other organisms that depend on the river for survival,” said Alexis Strauss, EPA’s Acting Regional Administrator for the Pacific Southwest. “It is essential that manufacturers take proper steps to prevent nurdles from polluting surrounding waterways and harming local wildlife.”

In 2016, during inspections at two other California facilities – Modern Concepts of Compton CA and Double R. Trading at City of Industry – EPA found inadequate containment measures that allowed plastic materials, including nurdles, to enter local waterways.

2005 photo of Charles Moore, founder of the Algalita Marine Research Foundation, and working to stop nurdle spills, is shown here with nurdles on the ground at a railroad /trans shipment area near a plastics manufacturing plant in the town of Vernon, CA, south of Los Angeles. Moore is also author of the 2011 book, “Plastic Ocean”. Photo, Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times.

Modern Concepts stores pre-production nurdles at its facility as part of its plastic products manufacturing process. EPA’s inspectors observed spilled plastic pellets on paved surfaces throughout the facility, which is located near Compton Creek, a tributary of the Los Angeles River. EPA also found the facility lacked pollution prevention equipment and used inadequate cardboard storage boxes, which exposed the pellets to rain and wind.

Double R. Trading Inc. operates a recycling plant that grinds plastic material into flakes that are ultimately exported to China. EPA inspectors discovered that the facility, when it was operating in Compton before moving to City of Industry, was discharging industrial stormwater into Dominguez Channel without a required permit. EPA inspectors observed large amounts of exposed plastic materials and fragments spilled on paved surfaces throughout the facility. The inspection found that the facility did not have necessary containment systems to trap plastic material and prevent releases to a waterway that flows into the Port of Los Angeles. Both companies cited by EPA in 2016 corrected their violations.

Since 2016, EPA and the California’s regional water boards have continued to cite plastics producers and processors for nurdle pollution. However, there are approximately 2,700 plastics facilities of one kind or another in the state of California that use or handle pre-production plastic nurdles, and it’s highly likely that many of them – and thousands more such facilities across the U.S. – are also losing nurdles to the environment.

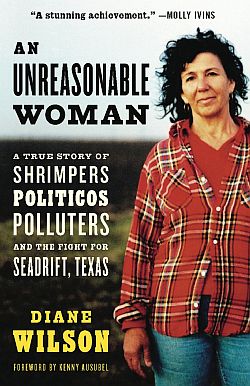

Citizen Activists

Diane Wilson’s book, “An Unreasonable Woman: A True Story of Shrimpers, Politicos, Polluters, and the Fight for Seadrift, Texas,” 2006 paperback edition, 392 pp. Click for copy.

Among her targets then and now was Formosa Plastics, the world’s sixth largest petrochemical company, which operates a sprawling 2,500-acre complex at Point Comfort, Texas. Formosa’s plant is in the middle of a rich biota of creeks, rivers, bays and wetlands that is the Texas Gulf Coast, between Galveston and Corpus Christi.

When Wilson learned from a former Formosa employee that the plant was losing lots of nurdles to the waterways and wetlands around the plant – notably Cox Creek and Lavaca Bay – she and a few others began collecting and documenting the plastic pollution. They found pellets everywhere they looked, and proceeded to catalogue their findings by place and date, storing them in Ziploc bags. In some spots, near discharge outlets and certain marshy areas, nurdle deposits were as much as five inches deep. After three years, Wilson and colleagues had collected more than 2,400 samples of Formosa’s pellet and powder pollution.

Wilson had also prodded Texas regulators to move on Formosa, and after a 2016 investigation, the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality found the company’s pellets in Cox Creek and Lavaca Bay and later fined the company $122,000. But in Wilson’s view, state fines were really not much of a deterrent for Formosa – more a cost of doing business. She believed more action was needed. That’s when the Waterkeeper v. Formosa lawsuit was started. Wilson had teamed up with the San Antonio Bay Estuarine Waterkeeper, a group she led, and also had legal help from Texas RioGrande Legal Aid, which represented the group.

For Diane Wilson, the battle with Formosa is personal. At one point she had told reporters she had a personal passion for Lavaca Bay: “To me it’s alive,” she said to a reporter with The Victoria Advocate. “It’s like a family member,” she said. “Formosa generally gets everything they want,” she explained. “…They’re not going to get the [bay]; …I drew a line, they’re not getting that bay.”

In July 2017, Wilson and team sued Formosa in Federal court under the citizen suit provision of the Clean Water Act. When the trial began in March 25, 2019 at the federal courthouse in Victoria, Texas, Wilson and team submitted their considerable haul of documented nurdle pollution – thirty plastic bins containing an estimated 26 million nurdles – which were stored in the courthouse basement for use during the trial.

Aerial photo of Texas Gulf Coast area showing location of Formosa Plastics’ 2,500-acre petrochem complex and areas polluted by the company’s pre-production plastic pellets, including Cox Creek and Lavaca Bay. Just beyond Matagorda Bay and Port O’Conner, to the right, is the Gulf of Mexico. Source: CrossroadsToday.com, Victoria, TX.

By late June 2019, U.S. District Judge Kenneth M. Hoyt ruled against Formosa, calling the company a “serial offender,” noting the company’s consistent violation of state-issued permits and federal laws. He was also moved by the evidence Wilson and team had brought to his courtroom. “These witnesses provided detailed, credible testimony regarding plastics discharged by Formosa, as well as photographs, videos, and 30 containers containing 2,428 samples… of plastic pellets,” he wrote in his opinion. The company’s illegal discharges, he noted, were “extensive, historical, and repetitive,” and that Formosa had violated the Clean Water Act by discharging plastic pellets and PVC powder into Lavaca Bay and Cox Creek. Hoyt found there were 736 days of illegal releases at one of Formosa’s water discharges and a total of 1,149 at eight others.

January 2020. Diane Wilson in her kayak, checking out the waters near Formosa’s plant for pellet pollution.

In the “penalty phase” of the Formosa trial, in October 2019, the plaintiffs had sought the maximum fine of $166 million. The company’s profits were then running at about $900 million a year. In the end, Formosa agreed to pay $50 million over five years. It was largest Clean Water Act citizen suit settlement filed by private individuals. The money was placed in a trust to help fund local conservation projects and scientific research. Formosa was required to comply with a “zero discharge” of plastic pollutants in the future and cleanup its existing pellet pollution. The settlement agreement also provided for ongoing oversight with a remediation consultant, engineer, and trustee, as well as fines for any continued nurdle pollution. Wilson and team have continued to monitor Formosa’s performance, and during early 2022, they found continued nurdle pollution from Formosa, which by then had cost the company nearly $4 million in new fines under terms of the agreement. An independent monitor tracks new spills, and the company will be working over the next few years to clean up its past pellet spills along Cox Creek and Port Lavaca Bay.

Wilson, meanwhile, was also contacted about reports that a ChevronPhillips plastics plant, not far from Point Comfort in Sweeney, Texas had also been releasing nurdles to the environment. Company officials there denied there was any such pollution. But Wilson, visiting the area with reporters and venturing into the wetlands and a discharge area near that plant, found pellets there as well. A spokesman for ChevronPhillips said those pellets were from a one-time storm incident that had since been corrected.

The Nurdle Patrol

Jace Tunnell, founder of The Nurdle Patrol, is a marine biologist and director of the Mission-Aransas National Estuarine Research Reserve at Port Aransas, TX.

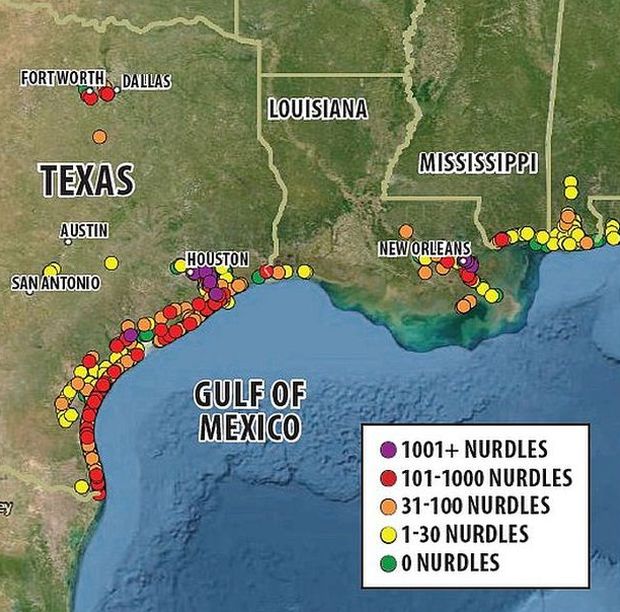

The Nurdle Patrol quickly grew beyond Texas, with volunteers in Mississippi, Florida, and Mexico participating. Tunnel’s email box was overwhelmed with 300-to-500 incoming submissions per month. By 2019, The Nurdle Patrol was a going concern, with its own website and reporting coming in from all over the U.S. and beyond. A map was created as well, displaying all the reporting locations in the U.S. and Gulf of Mexico region.

Nurdle Patrol, sample results plotted on map for Gulf Coast states. Click for current U.S. map at Nurdle Patrol website.

Jace Tunnell, meanwhile, was soon giving talks all around the country on the Nurdle Patrol, what it was finding, and what it hoped to achieve. Among the possibilities for Nurdle Patrol data, for example, is to link nurdles and nurdle spills to their manufacturers. Another is to push nurdle regulation, a need Tunnell discovered at his first encounter with the pellet problem on the beaches of Corpus Christi, when neither the U.S. Coast Guard nor the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality would do anything about the nurdle spill.

Jace Tunnell, who often patrols for wayward nurdles himself, is shown here in 2019, photographing nurdles being covered by wind-blown sand on a beach at Mustang Island, Texas. Photo, Jamie Smith Hopkins / The Center for Public Integrity.

Jace Tunnell and Diane Wilson aren’t alone these days. As mentioned earlier, citizen reporting of nurdle pollution is also a worldwide activity, with several environmental, NGO, foundation, and scientific organizations now involved in reporting and documenting nurdle pollution and/or related research. Some have also taken the fight to the investment arena. As You Sow, an environmental group, filed corporate shareholder resolutions in 2019 at ExxonMobil, ChevronPhillips, and Dow Chemical calling on those companies to disclose to shareholders when, where, and how much plastic pellets they have spilled each year and what they are doing to prevent such spills. And while there are new laws in a few places like California aimed at nurdle pollution and single-use plastic, and others in recent years that have phased out the use of micro beads in certain products, there is much more to do in bringing the global plastics behemoth to account.

More Plastic

Expansionist Binge

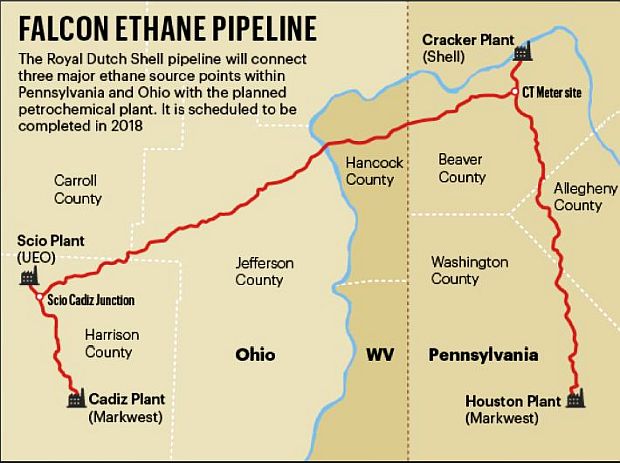

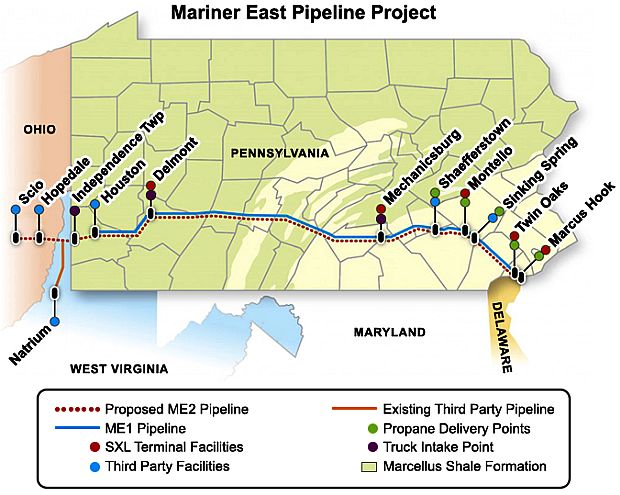

Nurdle pollution – and the larger plastics problem – will not likely end anytime soon. In fact, it may get worse before it gets better. Since about 2010, the plastics industry has been on an expansionist binge, driven in part by the cheap fracking gas that begins the plastics-making process. Oil and chemical companies, also seeing their traditional businesses potentially circumscribed in the future by climate change restrictions and new solar, wind, and electric car technologies, have embarked on a major plastics and petrochem building boom as a new growth strategy. Since 2010, oil and petrochemical companies have invested $200 billion in more than 300 plastic and other chemical projects in the U.S.

A general look at the steep rise of projected global plastic production in recent years, with share by region.

In Louisiana in early 2019, South African company Sasol Ltd. opened the first of seven new virgin plastic plants planned for its Lake Charles complex.

In St. James Parish, Louisiana, along the Mississippi River north of New Orleans, Formosa is proposing a 2,400-acre, $9.4 billion plastics complex that is currently being fought by local community activists and environmental groups.

And in Pennsylvania, a giant new ethane cracker built by Shell Oil just north of Pittsburgh is slated to come on line in late 2022. That plant will turn out the equivalent of 80 trillion nurdles per year for plastic makers all across the country. And there are other new plants and expansions to come in the build-out now underway.

In recent years, 35-to-40 percent of North American plastic resin production has been exported, and that share is slated to rise in the years ahead. That means more truck and rail trans-shipments of nurdles will crisscross the country to American ports, including those at Houston, TX; New Orleans, LA: Long Beach, CA; Savannah, GE; Charleston, SC; and New York, NY. Thousands of 20- and 40-foot containers full of nurdles will be packed onto large ocean-going container vessels destined for overseas plastics producers.

Beyond the U.S., plastics plants in Scotland and Belgium will be expanded in those petrochemical hubs as well. In January 2019, Ineos, a Swiss-registered chemical giant, chose Antwerp as the site for two new plants: an ethane cracker to make ethylene, and another to convert propane into propylene. That investment will boost Antwerp’s position as the second-largest petrochemical hub in the world after Houston.

Plastic pellets inside a dead fish washed ashore after Sri Lankan spill, 2021. Photo, Saman Abesiriwardana/Pacific Press & The Guardian.

See also at this website, “Plastic Infernos: A Short History” (plastic implicated in spread & severity of deadly fires); “Petrochem Peril: Shell Cracker History” (Shell Oil plastics plant & related infrastructure in Pennsylvania); “Phillips Explo-sion, 1989” (Phillips Petroleum plastics plant, Pasadena, TX); “Shell Plant Explodes, 1994” (Shell Oil plastics plant, Belpre, OH); and, “Environmental History: Selected Stories” (topics page with more than a dozen story choices).

Thanks for visiting – and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research, writing and continued publication of this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

____________________________________

Date Posted: 3 November 2022

Last Update: 25 June 2023

Comments to: jackdoyle47@gmail.com

Twitter: https://twitter.com/PopHistoryDig

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Nurdle Apocalypse: Plastic on the Loose,”

PopHistoryDig.com, November 3, 2022.

____________________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

“What Are Nurdles?,” Fauna & Flora Interna-tional / Fauna-Flora.org.

“Plastic Pellet Pollution,” Wikipedia.org.

Nurdle Patrol Website, NurdlePatrol.org.

Zoë Schlanger, “Virgin Plastic Pellets Are the Biggest Pollution Disaster You’ve Never Heard Of,” Quartz.com, August 19, 2019, updated July 20, 2022.

Dr. Chris Sherrington, “Plastics in the Marine Environment,” Eunomia.co.UK, June 1, 2016.

Miriam Berger, “Why Plastic Pellets Called ‘Nurdles’ Are Threatening Miles of Sri Lanka’s Coastline,” WashingtonPost.com, June 1, 2021.

Michael E. Miller, “A Burning Ship Covered Beautiful Beaches in Plastic ‘Snow.’ Now Sri Lanka Faces an Environmental Disaster,” WashingtonPost.com, June 1, 2021.

Aanya Wipulasena, “Dead Animals Wash Ashore in Sri Lanka After Ship Spills Chemicals; at Least Four Whales, 20 Dolphins and 176 Turtles Are Among the Dead as the Nation Grapples with its Worst Environmental Disaster,” NewYorkTimes.com, June 30, 2021, updated August 10, 2021.

Zinara Rathnayake in Colombo, “‘Nurdles Are Everywhere’: How Plastic Pellets Ravaged a Sri Lankan Paradise,” The Guardian.com, January 25, 2022.

Tine Hens, “The Great Spill of the Plastics Industry: Mountains of Nurdles on the Beach; Each Year 230,000 Tons of Plastic Pellets Pollute Riverbanks, Beaches and Oceans,” MO.be – MO* Magazine, July 6, 2019.

Alison Smith, “Residents Say Plastic From MV Rena Still Washing Up in Tairua, Waihi Beach,” NZHerald.co.nz, June 25, 2020.

Ella Stewart, “Rena Shipwreck Debris Suspected to Be Behind Plastic Bead Mystery at Tairua Beach,” RNZ.co.nz, June 16, 2021.

Julie Dermansky, “A Plastics Spill on the Mississippi River But No Accountability in Sight,” DeSmog.com, August 11, 2020.

Julie Dermansky, “Pollution Scientist Calls Plastic Pellet Spill in the Mississippi River ‘a Nurdle Apocalypse’,” DeSmog.com, August 28, 2020.

Tristan Baurick, “Mississippi River Nurdle Spill Inspires Effort in Congress to Curb Plastic Pollution,” Nola.com, September 29, 2020.

Jacob Wallace, “When Plastic Pours into the Mississippi, Who’s Responsible?,” Greenwire / Eenews.net, September 29, 2020.

Neel Dhanesha, “The Massive, Unregulated Source of Plastic Pollution You’ve Probably Never Heard Of,” Vox.com, May 6, 2022.

“The Great Nurdle Hunt; Tackling Worldwide Nurdle Pollution,” NurdleHunt.org.uk (FI-DRA /Scotland).

“Sinopec Plastic Pellet Disaster Worsens,” JourneyToThePlasticOcean.WordPress.com, July 28, 2012.

Benjamin Gottlieb, “Hong Kong’s Plastic Pellet Problem,” WashingtonPost.com, August 6, 2012.

“Hong Kong Cleans Up Massive Plastic Spill,” WSJ.com / Wall Street Journal, August 6, 2012.

Heather Caliendo, “First-Hand Account of the Hong Kong Plastic Pellets Clean Up,” PlasticsToday.com, September 7, 2012.

“Hong Kong Plastic Disaster,” Wikipedia,org.

“Dutch NGO Releases Evidence of Shocking Nurdle Pollution,” NurdleHunt.org.uk, Janu-ary 17, 2020.

“Millions of Plastic Nurdles Pollute Oslofjord in Norway,” PlasticSoupFoundation.org, May 20, 2020.

“At Least 24 Million Nurdles Washed up on Dutch Beaches; Amsterdam,” PlasticSoup Foundation.org, March, 14, 2019.

Rebecca Williams, “Nurdle Hunt Helps Tackles Millions of Plastic Pellets Washed Up on UK Shores,” Sky.com / Sky News, UK, February 6, 2017.

“Plastic Nurdles Found Polluting 73% of UK Beaches,” Sky.com / Sky News, UK, February 17, 2017.

“South Africa’s Ecological ‘Nightmare’ After Plastic Pellets Spill,” Sky.com / Sky News, U.K,, February 24, 2018.

Therese M. Karlsson, Lars Arneborg, Göran Broström, Bethanie Carney Almroth, Lena Gipperth, and Martin Hassel Löva, “The Unaccountability Case of Plastic Pellet Pollution,” Marine Pollution Bulletin, Vol. 129, No, 1, April 2018, pp. 52-60.

“The Great Global Nurdle Hunt Shows Worldwide Nurdle Pollution,” NurdleHunt .org.uk, March 4, 2019.

Eckart H. Schumann; C. Fiona MacKay, Nadine A. Strydom, “Nurdle Drifters Around South Africa as Indicators of Ocean Structures and Dispersion,” South African Journal of Science, Vol.115, No. 5-6, Pretoria, May/June 2019.

Dian Spear, “Nurdle Spills Point to a Bigger Problem of Too Much Plastic,” Daily Maverick.co.za, July 22, 2021.

Karabo Mafolo, “NGOs Call on Cape Town Beachgoers to Help Clean up Debris from Massive Nurdle Spill,” DailyMaverick .co.za, October 27, 2020.

Thomas Manch, “Manufacturer Accused of Spilling Thousands of Plastic ‘Nurdles’ into Wellington Harbour,” Stuff.co .NZ, June 22, 2018.

Edward J. Carpenter, Kenneth L Smith, Jr., “Plastics on the Sargasso Sea Surface,” Science, March 17, 1972.

Edward J. Carpenter, Susan J. Anderson, George R. Harvey, Helen P. Miklas and Bradford B. Peck, “Polystyrene Spherules in Coastal Waters,” Science, November 17, 1972, Vol 178, Issue 4062, pp. 749-750.

J. Hammer, M. Kraak, J. Parsons, “Plastics in the Marine Environment: The Dark Side of a Modern Gift,” Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 2012, Vol, 220, pp. 1-44.

Murray R. Gregory, “Plastic Pellets on New Zealand Beaches,” Marine Pollution Bulletin, Volume 8, Issue 4, April 1977, pp. 82-84.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), 1990 Report to Congress, “Methods to Manage and Control Plastic Wastes” (EPA identified plastic pellets as an item of particular concern), EPA, 1990a.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Water, Plastic Pellets in the Aquatic Environment: Sources and Recommenda-tions, Final Report, December 1992, 108 pp.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Water, “Plastic Pellets in the Aquatic Environment: Sources and Recommendations: A Summary,” August 1993.

Julissa Treviño and Undark, “The Lost Nurdles Polluting Texas Beaches; Tiny Plastic Building Blocks Are Spilled into Oceans and Waterways Before They’re Even Made into Plastic Goods,” TheAtlantic.com, July 5, 2019.

News Staff, “Cleanup Underway after Massive Train Derailment in Harmar Township (PA),” WPXI.com, May 26, 2022.

Andy Sheehan, “Derailed Train Leaked 3,000 Gallons of Petroleum Distillate into Water, EPA Says, Pittsburgh,” KDKA news report / CBS.com / Pittsburgh, PA, May 30, 2022.

“Pittsburgh Meets Nurdles Following Train Derailment,” bobscaping.com / Three Rivers Waterkeeper, June 1, 2022.

Philip Joens, “Union Pacific Train Derails East of Carlisle, Iowa, Leaking Plastic Pellets into Middle River,” DesMoinesRegister.com, November 2, 2021.

Lori Monsewicz, “Plastic Pellets Spilled in Canton Train Derailment,” CantonRep.com, April 26, 2013.

eustatic, “Post-Ida Nurdle Spill from Plastic Rail Car Derailment: Lessons from Raceland,” PublicLab.org, September 9, 2021.

Scott Eustis, “U.S. Railroad Plastic Pellet Spill Locations Since 2010 [National Response Center (NRC) data in which a rail car plastic spill is noted], via Google.com/maps.

“Polluting Plastic Particles Invade the Great Lakes,” ACS.org / American Chemical Society, April 8, 2013.

John Schwartz, “Scientists Turn Their Gaze Toward Tiny Threats to Great Lakes,” NYTimes.com, December 14, 2013.

Lisa W. Foderaro, “Study Investigates Proliferation of Plastic in Waterways Around New York,” NYTimes.com, February 18, 2016.

“Rossport Beach Cleanup…Nurdles Under-current,” InfoSuperior.com, October 15, 2018.

Patricia L. Corcorana, Et al., “A Comprehensive Investigation of Industrial Plastic Pellets on Beaches Across the Laurentian Great Lakes and the Factors Governing Their Distribution,” Science of The Total Environment, Vol. 747, December 10, 2020.

Garret Ellison, “Industrial Plastic Pellets Called ‘Nurdles’ Are Littering Great Lakes Beaches,” MLive.com, September 8, 2021, updated: January 26, 2022.

Petri Bailey Blog: “Nurdle Alert: Plastics Spill Sweeping Lake Superior,” CELA.ca, April 3, 2020.

Inayat Singh, Alice Hopton, “Industrial Plastic Is Spilling into Great Lakes, and No One’s Regulating It, Experts Warn,” CBC News / CBC.ca, September 27, 2021.

News, “Groups File Lawsuit Against Frontier Logistics over Plastic Pollution,” Southern Environment.org, March 19, 2020.

David Wren, “Judge Chides SC Plastic Pellet Packager, Says Environmental Lawsuit Will Proceed,” PostandCourier.com (Charleston, SC), September 22, 2020.

Associated Press, “SC Bill Would Crack Down on Plastic Pellet Spills,” PostandCourier.com, March 24, 2021, updated June 23, 2021.

News, “Frontier Logistics Agrees to $1.2 Million Settlement in Pellet-Pollution Law-suit,” SouthernEnvironment.org, March 3, 2021.

Sharon Kelly, “$1 Million Nurdle Spill Settlement Shines Light on Plastic Pollution During Shipping,” DeSmog.com, March 9, 2021.

Chloe Johnson, “SC Ports Fights Against Lawsuit Discovery in Case about Plastic Pellet Spill,” PostAndCourier.com, November 16, 2020, Updated March 24, 2021.

Editorial, “$1 Million Settlement Underscores Need for Nurdles Regulation, SPA Openness,” PostAndCourier.com, March 5, 2021; updated June 7, 2022.

Joseph Bonney, Senior Editor, “Charleston Attracts Share of US Gulf Resin Exports,” Journal of Commerce / JOC.com, April 27, 2017.

Caroline Balchunas, “National Database Ranks Charleston Second-Worst for Plastic Pellet Pollution,” ABCnews4.com, December 17, 2019.

David Wren, “Plastic Pellet Packagers Set to Bring More Exports Through Charleston Port,” PostandCourier.com, September 27, 2020.

Faculty & Staff, “Company Accused of Polluting Ocean with Plastic Has an Ally: SC Ports,” Today / Citadel.edu, October 7, 2020.

Carol Thompson, “Thousands of Plastic Pellets Have Spilled into Waterways in Poconos: ‘This Is Going to Be Extremely Challenging’,” The Morning Call / MCall.com (Allentown,PA) April 5, 2018.

Associated Press (Tannersville, PA), “Crash Sends Millions of Plastic Pellets into State Waterways,” April 5, 2018.

Kurt Bresswein, “How to Help Clean up Plastic Pellets Spilled in Delaware River Tributary,” LehighValleyLive.com, April 14, 2018.

Simon Little, “Industrial Plastic Pellets Spilling into Fraser River, Salish Sea: Environmental Group,” GlobalNews.ca, October 4, 2019.

Katya Slepian, “‘Outrageous’: Environmental Group Urges Action from B.C. on Plastic Pellets in Waterways; Plastic Pellets Are Being Eaten by Fish, Birds, Turtles,” Vernon MorningStar.com (Vernon, B.C,, Canada), February 3, 2020.

S.L Moore, D. Gregorio, M. Carreon, S. B.Weisberg, M. K. Leecaster, “Composition and Distribution of Beach Debris in Orange County, California,” Marine Pollution Bulletin, Volume 42, Issue 3, March 2001, pp, 241-245.

Letter to: Metro Poly Corporation, San Leandro, CA, Re: “Notice of Violation for Storm Water Exposure and Discharging Without Industrial Storm Water General Permit Coverage; Corrective Actions Required,” from, California Regional Water Quality Control Board, San Francisco Bay Region, Oakland, CA, March 9, 2010 (w/ inspection report & photos, 41 pp.).

“Plastic Pellet Clean-up Begins in S.F. Bay,” UPI.com, October 28, 2011.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, News Release, “California Water Boards, U.S, EPA, Launch Unique Effort to Eliminate ‘Nurdles’ From San Francisco Bay; Government Ordered Cleanup of Illegally Discharged Plastic Pellets Will Protect San Francisco Bay, Endangered Species,” EPA.gov/ Region9, October 28, 2011.

“EPA Fines Two California Firms for Resin Pellet Pollution,” PlasticsNews.com, July 14, 2017.

“EPA: Southern California Plastic Manu-facturers Must Protect L.A. River From Pollution; Two Southern California Plastic Product Manufacturers to Resolve Federal Clean Water Act Violations,” WaterTechOnline .com, July 17, 2017.

“San Francisco Bay Water Board Focus on Pre-Production Plastics (commonly known as ‘nurdles’),” Waterboards.CA.gov / San Fran-cisco Bay, last updated, August 28, 2017.

News Release, EPA, Region 9, “U.S. EPA Requires Two Los Angeles Area Plastics Manufacturers to Protect Local Waterways,” EPA.gov, May 16, 2018.

Amy Westervelt, “It’s Taken Seven Years, but California Is Finally Cleaning up Microbead Pollution; Nonprofits Are Using the State’s New Stormwater Requirements to Sue Plastic Manufacturers for Polluting Waterways — and They’re Winning,” TheGuardian.com, March, 27, 2015.

“Diane Wilson,” Wikipedia.org.

“Formosa Plastics Corp,” Wikipedia.org.

Myron Levin / FairWarning, “Tenacious Citi-zens Take on the Plastics Industry over an Insidious Pollutant,” InvestigativeReporting Workshop.org, September 17, 2020.

Marissa Luck, “Formosa’s Texas Plant Fined $122,000 for Plastic Pellet Spill,” Houston Chronicle / Chron.com, January 17, 2019.

Lily Moore-Eissenberg, “Nurdles All the Way Down; How Texans Are Taking on Plastic Pollution—One Piece at a Time,” Texas Monthly, October 2019.

Amber Joseph, “Residents Sue Formosa Plastics for Polluting Lavaca Bay; Seeking $57 Million in Penalties for Breaking Environmental Laws,” CrossroadsToday.com, August 4, 2017, updated, February 5, 2021.

Julie Dermansky, “Activists Find Evidence of Formosa Plant in Texas Still Releasing Plastic Pollution Despite $50 Million Settlement,” DeSmog.com, January 18, 2020.

Beth Gardiner, “How a Dramatic Win in Plastic Waste Case May Curb Ocean Pollution,” NationalGeographic.com, Febru-ary 22, 2022.

Final Consent Decree, Cause No. 6:17-CV-00047, re: San Antonio Bay Estuarine Waterkeeper and S. Diane Wilson, vs. Formosa Plastics Corp., Texas and Formosa Plastics Corp., U.S.A., in the U.S. District Court, Southern District of Texas, Victoria Division, December 9, 2019.

“Archiving Formosa Plastics,” Disaster-STS-Network.org.

Leo Bertucci, “First Phase of $50 Million Formosa Pellet Cleanup to Start This Month,” Victoria Advocate.com, October 6, 2022.

Jace Tunnell, Mission-Aransas National Estuarine Research Reserve, “Hurdles with Nurdles: Gulf-Wide Citizen Science Project,” April 17, 2019.

NOAA Ocean Podcast: Episode 31, “The Nurdle Patrol: Citizen Scientists Fight Pollution, One Pellet at a Time,” National Ocean Service / NOAA.gov / National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, January 2020.

Callie Rainosek, “Jace Tunnell: Father, Scientist, Conservationist, and Nurdle Enthusiast,” TexasSeaGrant.org.

Xiangtao Jiang, Kaijun Lu, Jace Tunnell, and Zhanfei Liu, University of Texas Marine Science Institute, “Mapping Distribution and Chemical Levels of Nurdles in the Coastal Bend,” Final Report, August 2021, Submitted to: Coastal Bend Bays & Estuaries Program, Corpus Christi, Texas.

Melanie Quan, “Analysis of Plastic Pellet Distribution Using Citizen Science Nurdle Patrol Data and Batch Identification to Differentiate Spills Within Samples” (under the direction of Colleen Johnson, Project Scientist, EarthCon Consultants, Inc.; Jace Tunnell, Reserve Director, University of Texas Marine Science Institute, Research Science Institute), July 27, 2020.

Sally Palmer, “Nurdle Patrol Expands its Citizen Scientist Effort to Fight Plastic Pollution on Beaches,” UTexas.edu, September 29, 2021.

Graysen Golter, “Scientist’s ‘Plastic Patrol’ Expands Reached to Mexico,” Port Aransas South Jetty /portasouthjetty.com, January 5, 2022.

Center for International Environmental Law, “Fueling Plastics: How Fracked Gas, Cheap Oil, and Unburnable Coal are Driving the Plastics Boom,” CIEL.org, September 2017.

Jamie Smith Hopkins, “As the World Grapples with Plastic, the U.S. Makes More of it — A Lot More,” PublicIntegrity.org, June 13, 2019.

Zoë Schlanger, Justin Cook, and Katie Peek, “A New Plastic Wave Is Coming to Our Shores; A Glut of Natural Gas Has Led to a U.S. Production Surge in Tiny Plastic Pellets, Called Nurdles, That Are Washing up on Coasts by the Millions,” Audubon Magazine, Summer 2020.

Sharon Kelly, “Why Plans to Turn America’s Rust Belt into a New Plastics Belt Are Bad News for the Climate” [part of series: “Fracking for Plastics”], DeSmog.com, October 28, 2018.

Bill Mongelluzzo, “Long-Awaited U.S. Resin Boom Seen Emerging,” JOC.com / Journal of Commerce, January 2, 2019.

CIEL, et. al, Plastic & Climate: The Hidden Costs of a Plastic Planet, CIEL.org, May 2019.

Bill Mongelluzzo, “US Resin Exports Rocketing as New Plants Come Online,” October 24, 2019.

C.J. Moore, G.L. Lattin, A.F. Zellers, “Measuring the Effectiveness of Voluntary Plastic Industry Efforts: Algalita Marine Research Foundation’s Analysis of Operation Clean Sweep,” 2005, Algalita Marine Research Foundation, Long Beach, CA.

Aria Bendix, “Tiny Pellets Called ‘Nurdles’ Are Leeching into the Ocean. A New Shell Plant Could Produce 80 Trillion of Them a Year,” BusinessInsider.com, August 21, 2019.

Eline Schaart, “Antwerp’s Big Nurdle Battle; The Tiny Plastic Pellets Have Put a Major Chemicals Company on a Collision Course with Local Campaigners,” Politico.eu, February 3, 2020.

Chris Dupin, “Program to Prevent Plastic Pellet Pollution Criticized as Ineffective; There Should Be Individual Corporate Responsibility for Spills of Plastic Pellets, Says the Environmental Group, As You Sow,” American Shipper / FreightWaves.com, January 1, 2020.

Chelsea Rochman, University of Toronto, “Plastic Pellets Spell Big Problems for Our Ocean; Zero Pellet Loss Should Be the Rule, Not the Exception,” OceanConservancy.org, October 2, 2020.

Laura Sullivan, “Big Oil Evaded Regulation And Plastic Pellets Kept Spilling,” NPR News / IdeaStream.org, December 22, 2020.