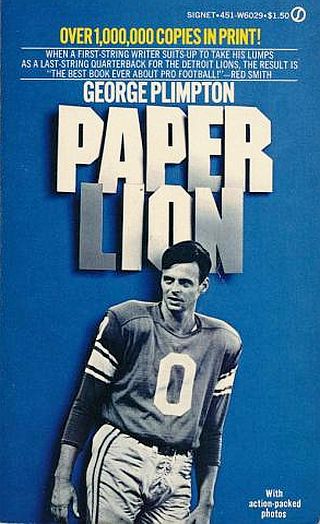

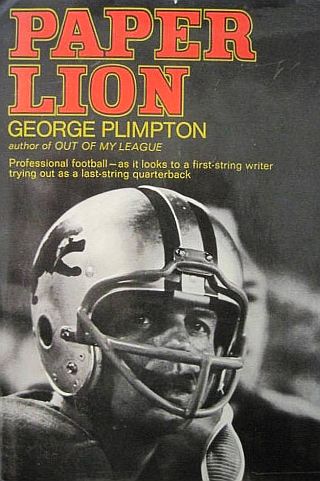

Signet paperback edition of George Plimpton’s best-selling book on his trials as a professional quarterback with the Detroit Lions football team, summer of 1963. Click for copy.

Plimpton – an amateur sportsman at best, but not a gifted athlete – wanted to experience the role of quarterback on a professional NFL team, all in the interest of discovering what it would be like for an average person to try that profession. He planned to write about the experience for Sports Illustrated, where he was a reporter, and would later publish a popular book about the experiment, Paper Lion, shown at right.

This was not the first time that Plimpton sought the experience of a professional athlete. In 1959, he went three rounds with light-heavyweight boxing champ, Archie Moore. And in professional baseball, Plimpton arranged in 1960 to pitch to a lineup of National and American League baseball all-stars in a post-season exhibition game at Yankee Stadium.

In that experiment, Plimpton proposed to pitch his way through each lineup once, and whichever team had the most total bases against him would win a monetary prize. Plimpton – although he had his moment of glory with Willie Mays popping out – was shelled pretty badly, and reportedly exhausted himself in the ordeal, needing a relief pitcher to finish.

Plimpton chronicled his pro baseball experience in the 1961 book, Out of My League. And in later years, he would do similar stints in other professional sports – from ice hockey to basketball, all to show how an average guy might fare in competition with the stars of professional sport. But Plimpton’s real genius in these undertakings – and hitting upon some unique journalistic territory – was the insider reporting he did on the sports cultures he experienced and player personalities he engaged along the way.

Summer of 1963. George Plimpton in his practice football attire at the Detroit Lions summer camp. |

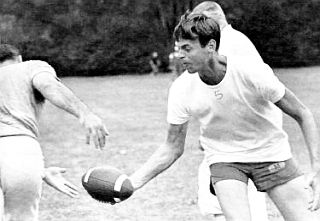

August 1963: George Plimpton, at center with ball, going through some practice drills at Detroit Lions camp, appears to be looking for a receiver with some trepidation. |

August 1963: George Plimpton, during a light-attire Detroit Lions practice session, is late with hand-off to running back. |

Football, of course, is a rough contact sport where an unknowing soul can be smashed around a good bit – all in fair play, to be sure. Yet the consequences can range from painful body blows and bruising in the least, to more serious assaults resulting in broken bones, knock-outs, and worse. Plimpton, 36 at the time, was in good health, but not a man acclimated to the pounding pro football players experience. Still, George Plimpton was game.

In his football quest, Plimpton had contacted several pro teams seeking approval to try out his plan. Among these were the Baltimore Colts, the New York Giants, and the New York Titans (predecessor to the New York Jets), all of which turned him down. But the Detroit Lions agreed to host Plimpton at their training camp. The un-athletic Plimpton arrived at the Lions camp in early August 1963 under the guise of a walk-on, former Harvard quarterback, competing for a possible back-up slot.

The coaches at first went along with the fable that Plimpton had come to their camp to try out as a backup quarterback. Detroit Lions players, meanwhile, at least initially, were not aware of the ruse. But once Plimpton hit the practice field it soon became apparent that the “new guy” had questionable football cred. In fact, he didn’t even know QB basics – like how to receive the snap from center.

Still, for several weeks, Plimpton was groomed in the finer art of quarterbacking by veteran Lion QBs Earl Morrall and Milt Plum, who helped him with the basics and offered advice

But along the way, Plimpton would have his troubles with the intricacies of the QB position. He made gaffe after gaffe. His hands and feet were too slow to make the quick-timing moves and spins QBs had to make with hand-offs and passing. The third photo here at left shows Plimpton during a light workout being too slow and missing a hand-off to one of his backs on a simple running play.

Yet as a journalist, he was seeing and learning about the game in a new, insider way – and that’s what he had come to do, though trying his best to measure up as a player. Fellow players thought it odd that Plimpton — tall and gangly, who described himself as having a physique akin to a tall wading bird — was always writing in a notebook between plays. When the players discovered that Plimpton was a writer, he took his share of ribbing and practical jokes. A handmade sign attached to a locker-room whirlpool, for example, read “reserved for Plimpton.” But he went along with all the good-natured fun and was gracious about the ribbing — including rookie hazing rituals.

Despite his struggles on the field, Plimpton managed to convince head coach George Wilson to let him take some snaps and run the team at an upcoming “big game” – an intra-squad exhibition contest – where he was given a chance to run a series of plays.

August 1963. George Plimpton taking some practice snaps prior to the intra-squad game. |

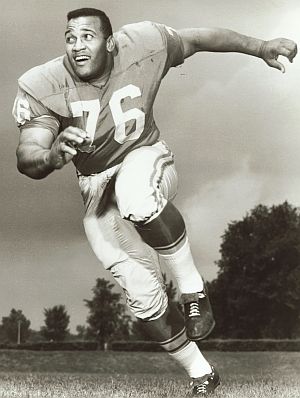

On one play, Plimpton was met in the backfield by giant 300-pound defender, Roger Brown, who threw him for a loss and nearly forced a fumble for a touchdown. |

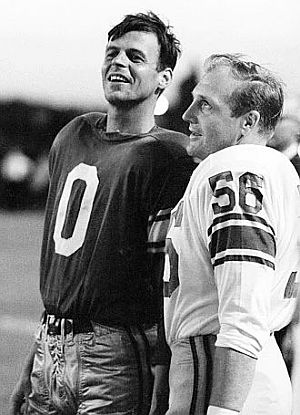

After his shot at QB, Plimpton talks with Joe Schmidt, No. 56, the linebacker who opposed him during his series of downs. Sports Illustrated photo. |

The annual intra-squad scrimmage was conducted in Pontiac, Michigan, and Plimpton rode the bus with the team to the contest, sitting alongside a veteran player, seeking his counsel and advice along the way. When Plimpton got his chance, he managed to lose yardage on each play.

Plimpton first wrote about his Detroit experience in Sports Illustrated in two articles, covering both his time in training camp and his shot at QB in the “big game” intra-squad contest. Plimpton wrote in a self-effacing, humorous manner about his own play, while accurately describing the mechanics of the game and sometimes capturing the more colorful side of his Lion teammates. Below, he describes his third play at QB in the intra-squad game, after his first two attempts had gone for bust:

…The third play on my list was the 42, another running play, one of the simplest in football, in which the quarterback receives the snap, makes a full spin and shoves the ball into the 4 back’s stomach. He has come straight forward from his fullback position as if off starting blocks, his knees high, and he disappears with the ball into the No. 2 hole just to the left of the center—a straight power play and one which seen from the stands seems to offer no difficulty.

I got into an awful jam with it. Once again the jackrabbit speed of the professional backfield was too much for mc. The fullback, Danny Lewis, was past me and into the line before I could complete my spin and set the ball in his belly. The fullback can’t pause in his drive for the hole, which is what he must keep his eye on, and it is the quarterback’s responsibility to get the ball to him. The procedure in the forlorn instance of missing the connection and holding the ball out to the seat of the fullback’s pants as he tears by is for the quarterback to tuck the ball under his arm and try to follow the fullback into the line, hoping that he may have budged open a small hole.

I tried to follow Lewis, grimacing, and waiting for the impact, which came before I’d taken two steps. I was grabbed up by Roger Brown, a 300-pound tackle. For his girth he is called Rhinofoot by his teammates, or Haystack, and while an amiable citizen off the field, with idle pursuits—learning very slowly to play the saxophone, a sharp dresser, affecting a narrow-brimmed porkpie hat with an Alpine brush—on the field he is the anchor of the Lions’ front line, an All-League player, and anybody is glad not to have to play against him.

He had tackled me high and straightened me up with his power, so that I churned against him like a comic bicyclist. Still upright, to my surprise, I began to be shaken around and flayed back and forth, and I realized that he was struggling for the ball. The bars of our helmets were nearly locked, and I could look through and see him inside—the first helmeted face I recognized that evening—the small, brown eyes surprisingly peaceful, but he was grunting hard, the sweat shining, and I had time to think, “It’s Brown, it’s Brown!” before I lost the ball to him. Flung to one knee, I watched him lumber into the end zone behind us for a touchdown.

The referee wouldn’t allow it. He said he’d blown the ball dead while we were struggling for it. Brown was furious. “You taking that away from me,” he said, his voice high and squeaky. “Man, I took that ball in there good.”…

While Plimpton’s big moment had met with failure, he remained confident he could do better, and conceivably might have another chance to play. And so he continued at training camp for another week as the team prepared for its first pre-season game against the Cleveland Browns.

Plimpton believed that if the Lions had a big enough lead near the end of that game, coach Wilson would let him play. However, team officials inform Plimpton at halftime that NFL Commissioner Pete Rozelle would not allow him to play under any circumstance. The next day, Plimpton cleaned out his locker space and ended his sojourn with the Detroit Lions. But at his departure, the Lions team awarded him a gold football engraved as follows: “To the best rookie football player in Detroit Lions history.”

About a year later, in September 1964, Plimpton would publish his two long pieces in Sports Illustrated magazine on his adventures at the Lions’ training camp and his QB action.

1966. Harper & Row first edition hardcover of George Plimpton’s book, “Paper Lion,” including photos of Plimpton in drills during Lions’ football camp. Click for copy.

“Paper Lion has vivid details, exuberant humor, a powerful narrative arc and a polished, sophisticated diction, all of which suggested a young craftsman pushing himself to the limit,” observes Scott Sherman, writing on Plimpton for The Nation in 2009.

The 362-page book wasn’t just about Plimpton’s own trials on the field, but also covered the players and coaches he came to know in his month or more association with them.

Among those featured in the book were linebacker Wayne Walker, quarterback Milt Plum, future Hall of Famers cornerback Dick “Night Train” Lane, middle linebacker Joe Schmidt, and defensive tackle Alex Karras. Karras, however, had missed the 1963 season, then serving a suspension for gambling on football games, so his profile came by way of stories about him told to Plimpton teammates, coaches, and others (Plimpton would do more with Karras in a later book). Paper Lion was also a great read for football fans. It not only captured what it might feel like for the average fan to try out for a professional football team, it also had inside information and a locker-room perspective.

Plimpton’s book became a best seller. And in subsequent paperback editions, Paper Lion received a bit more hype, as the Vantage edition at the top of this story notes: “Over 1,000,000 copies in print!” That edition also used the cover tagline: “When a first string writer suits up to take his lumps as a last-string quarterback for the Detroit Lions the result is ‘the best book ever written about football’ – Red Smith”. Then came the film.

“Paper Lion,” the movie, was a 1968 sports comedy film starring Alan Alda as Plimpton, based on Plimpton’s book. The film also depicted his tryout with the Detroit Lions. It premiered in Detroit on October 2, 1968, and was released nationwide the following week. In the movie, unlike the book, Plimpton does well in the scrimmage and scores a touchdown, only to realize that the defense purposely loosened up and allowed him to score.

In the film, a number of Detroit Lions players appear in brief scenes, among them: Joe Schmidt, Alex Karras, John Gordy, Mike Lucci, Pat Studstill, Roger Brown, Lem Barney, and Garo Yepremian. Coach George Wilson also appeared, as did Green Bay Packers’ coach, Vince Lombardi in one scene, although that scene was not in the book. Frank Gifford, former New York Giants halfback and sportscaster, also appeared. Film posters and tie-in editions of the Plimpton book, both used variations on the tagline: “The Paper Lion is About to Get Creamed.”

More than 20 years after the film, Plimpton’s son, Taylor, noted some differences in Alan Alda’s portrayal of Plimpton in his Detroit Lion’s venture, explaining: “Alda’s version was always angry or consternated, like a character in a Woody Allen film, while my dad, though he certainly faced hurdles as an amateur in the world of the professional, bore his humiliations with a comic lightness and charm—much of which emanated from that befuddled, self-deprecating professor’s voice.”Plimpton’s book, meanwhile, went on to live a long paperback life. Paper Lion was reissued in 2011 with a new look for its 45th anniversary edition.

In subsequent years, Plimpton would go on to chronicle other professional sports – and also non-sport professions – in the participant-journalist mold. Not all of these would become book-length treatments, and some would be published as magazine articles or as parts of other books. And Plimpton’s books were not always completely about his experimental participation, as his stories would also include perspective on the special insider access he had, and/or profiles of related people and activity surrounding the subject sport he had chosen.

Plimpton’s first sports book in the participant journalist mold had been his 1961 book about pitching to the major league baseball All Stars, Out of My League. A cover blurb on the hardback edition noted: “A weekend athlete and a full-time man of letters recalls his eye-opening and very funny experience pitching against the greatest pros in baseball.” The book touched upon many of the famous players of that day, including Mickey Mantle, Billy Martin, Willie Mays, Ernie Banks, Whitey Ford, Ralph Houk, Richie Ashburn, and others. It also included a number of photos of Plimpton and other players, either in action or in the dugout, among them: Stan Lopata, Frank Thomas, Bill Mazeroski, Bob Friend, and Don Newcombe. The baseball book was followed by Plimpton’s Detroit Lions stint in 1963 and the Paper Lion book in 1966.(Click on any book image for Amazon page on that book).

His third sports book came in 1967, The Bogey Man: A Month on the PGA Tour, a book about his experiences playing (with an 18 handicap) and traveling with the Professional Golfer’s Association (PGA) tour in the time of Arnold Palmer, Sam Snead and Jack Nicklaus. “Stroke-saving theories, superstitions, and other golfing lore,” are part of this Plimpton book, explained one reviewer. Another review in the New York Times noted that with Bogey Man Plimpton was probing the psychology of the sport, and on that count, “there is nothing more revealing around.”

A Life magazine blurb added: “Golf is a lonely and private game, lacking the natural drama of football, but Plimpton, by substituting improvisation for plot, has caught its mad comedy and bizarre effects on people in a book just as charming, in its own way, as Paper Lion.”

Mad Ducks & Bears: Football Revisited, is a 1973 book about Detroit Lions linemen, Alex Karras and John Gordy, which also includes extensive chapters on Hall of Fame quarterback Bobby Layne, as well as an account of Plimpton’s return to his “participant” football experience, this time with the Baltimore Colts. But the primary subjects in this book are Karras and Gordy. Says one Chicago Tribune blurb: “[An] irreverent and roguish account of the lives of the two linemen…. Pure gold.” The book was meant, in part, as a companion to Paper Lion.

Shadow Box: An Amateur in the Ring, is Plimpton’s 1977 book about boxing, which includes his own brief 1959 bout with then light-heavyweight champ, Archie Moore, in which Plimpton received a bloodied nose for his efforts. The book also includes Plimpton’s writing on the history of boxing, the Muhammad Ali-George Foreman fight in Zaire, as well as other bouts and character sketches of fellow writers Norman Mailer and Hunter Thompson.

Another Plimpton book published in 1977 is One More July: A Football Dialogue with Bill Curry, about the last NFL training camp of former Green Bay Packer player, center Bill Curry, who later became a football coach and sportscaster. A New York Times blurb for this book notes: “If a time capsule needed a history of pro football’s years from 1965 to 1975, this would be the book.”

Open Net: The Professional Amateur in the World of Big-Time Hockey, is Plimpton’s 1985 book about his experience playing professional ice hockey with the Boston Bruins. This time, Plimpton, at age 50, suited up as a goalie for an exhibition hockey game against the Philadelphia Flyers at the Spectrum arena in Philadelphia. As one account of that outing noted: “Plimpton, gangly even in his goalie pads, tends the net with a reporter’s notebook tucked in his uniform. His moment of reckoning comes on a Flyers penalty shot from Reggie Leach. Plimpton makes the save, but when a teammate slaps him on the back of the helmet in celebration, the game-winning goalie loses his balance and topples to the ice.”

Plimpton also did a book on Hank Aaron in 1974 – Hank Aaron: One for the Record – The Inside Story of Baseball’s Greatest Home Run. In this book, Plimpton recounts the play of baseball’s Hank Aaron in his 1974 bid to become the all-time home run champion, then eclipsing Babe Ruth’s previous record of 714 home runs. Aaron sought to beat Ruth’s record amid a media frenzy and even received some death threats. Plimpton, meanwhile, covers the pitchers who faced Aaron during this time, but the focus is on Aaron – his abilities, his philosophy on hitting, and his achievements.

In April 1985, Plimpton wrote a Sports Illustrated story about a baseball pitcher named Sidd Finch, a mysterious talent who reportedly threw pitches at an astonishing 168 mph and was signed by the New York Mets. Reportedly, Finch was an English-born Buddhist monk – Siddhartha – who had acquired his hurling skills by throwing rocks at snow leopards in the Himalayas. The Sports Illustrated story ran for 13-pages and came complete with spring training photos, scouting reports, and Mets player reaction. However, the story was an elaborate April Fools hoax perpetrated by Plimpton. But he liked the story so much he expanded it and turned it into a novel, published two years later by MacMillan – The Curious Case of Sidd Finch.

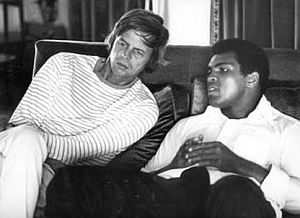

George Plimpton visiting with Muhammad Ali, likely in the 1970s. Plimpton wrote about Ali in “Shadow Box” and for Sports Illustrated.

In 2016, Nathaniel Rich, writing in the New York Review of Books, noted that Plimpton’s sports books “have aged gracefully and even matured. Today they have the additional (and unintended) appeal of vivid history, bearing witness to a mythical era.” A review of Plimpton’s work in The Guardian noted: “…With his gentle, ironic tone, and unwillingness to take himself too seriously, along with Roger Angell, John Updike and Norman Mailer, he made writing about sports something that mattered. He wrote about the way professional athletes coped with failure, ambition and envy, making them sound like interesting people.”

In his career as a sports journalist, Plimpton came to know and befriend some leading lights of the various professions, among them, Muhammad Ali, of whom he had written in his book, Shadow Box, and soccer great, Pele`, who blistered a shot past amateur goalie Plimpton during a documentary promotion. But beyond his forays into the world of sport and other professions, George Plimpton was a man of many dimensions, a kind of experiential renaissance man, who lived an incredibly full life and was well liked by many.

|

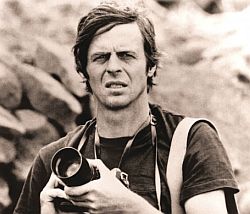

Man About Town George Plimpton  1972: George Plimpton photographing birds in Africa. Photo, Freddy Plimpton / WNET. Plimpton grew up on New York’s Upper East Side, attending St. Bernard’s School there and later, Phillips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire Although he tried out for most sports at Exeter, he never survived the cuts. Plimpton was also expelled from Exeter just shy of graduation. According to one account, he wasn’t very good at set schedules, and had been placed on disciplinary probation at Exeter for curfew violations. But then, after aiming a Revolutionary War-era musket at the football coach, he was expelled from Exeter. Still, after earning his high school diploma in Florida, he entered Harvard in July 1944, but did not graduate until 1950 due to his time in the U.S. Army, serving as a tank driver in Italy. Returning to Harvard, he majored in English, wrote for the Harvard Lampoon, was a member of the Hasty Pudding Club, Pi Eta, the Signet Society, and the Porcellian Club. After graduating from Harvard in 1950, he went on to Kings College at Cambridge, England for two years where he earned a graduate degree in English. In 1953, Plimpton joined the newly-created literary journal, The Paris Review, founded by writer Peter Matthiessen (The Snow Leopard) and others. Matthiessen made Plimpton the journal’s first editor in chief, a post he would keep until his death in 2003.  George Plimpton, shown here reading some papers for The Paris Review, and selected by writer and founding member, Peter Matthiessen, to be its editor in 1953, a post he served until his death in 2003. PBS photo. At the Review, Plimpton initially served as editor in Paris, France, but later the Review was moved to New York City, at Plimpton’s town home on the Upper East Side. Plimpton is credited with constructing the classic Paris Review interview with established writers, which became an important feature, engaging the subject in a collaborative process with corrections, revisions, and final sign-off. Plimpton viewed the interviews as a vehicle for established writers to explain their craft, not unlike what he would later do in a somewhat different vein as a reporter with his sports immersions. At the Review, Plimpton did classic interviews with figures such as E.M. Forster and Ernest Hemingway, among others. Some credit him with inventing the form, later adopted by Rolling Stone and Playboy magazines. In New York, meanwhile, his residence became known for its legendary cocktail parties, where all the important literati of that era would gather.  At 1963 party at his home in New York, Plimpton is shown seated at lower left. Among other notables attending were: William Styron, Gore Vidal, Jonathan Miller, Truman Capote, Arthur Penn, Mario Puzo, and Ralph Ellison. Photo, Cornell Capa. “George saw his home as a place for everybody,” said Sarah Plimpton, his second wife, in comments after his death in 2003. “He loved the lights blazing, piano playing, glasses clattering, and the more oddballs the better. He loved people so much that he felt something was missing if this house wasn’t full.” According to one New York Times accounting, “for more than 45 years, he was host to hundreds of parties for thousands of guests, sometimes at a rate of one a week.” Those visiting Plimpton at his office in his spacious townhouse on East 72nd Street in New York would notice his piles of papers and his somewhat disheveled dress and work manner, as well as his collection of framed and other memorabilia from his personal travels and friendships. Others marveled at how much life George Plimpton lived, how many balls he juggled at once, and the various projects he had underway or lined up.  George Plimpton traveled in a circle of the American elite and the otherwise famous through most of his life, shown here at the 1962 America’s Cup with Jackie and President John F. Kennedy and others. Photo, PBS. At Harvard, he was a classmate of and friend to Robert F. Kennedy, and would befriend the entire Kennedy family. In the early 1960s, he was a familiar figure at the RFK family place at Hickory Hill in northern Virginia, where he could be found playing touch football. In 1968, he and first wife, Freddy Espy Plimpton, were traveling with RFK when he was making his decision to enter the 1968 Democratic presidential race, and Plimpton also made campaign appearances on Kennedy’s behalf. Following RFK’s victory in the 1968 California Democratic primary, Plimpton, along with former decathlete Rafer Johnson and American football star Rosey Grier, was credited with helping wrestle RFK shooter, Sirhan Sirhan to the floor when Kennedy was assassinated at the former Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles. Bobby Kennedy’s son, RFK, Jr., would later say of Plimpton: “My father admired George for his courage; he had a curiosity about life and I think that’s the thing that probably attracted my father the most to him. Like my father, he saw life as a great adventure…” |

1977: Plimpton trying his hand as race car driver. (AP Photo) |

1970: Playing bad guy shot by John Wayne in 'Rio Lobo' film. |

1970s: In real life, a father of four; here with son Taylor. |

Sept 2003: Alex Karras and George Plimpton at 40th “Paper Lion” reunion at Ford Field in Detroit. Karras, featured in “Mad Ducks & Bears,” became lifelong Plimpton friend. |

In addition to his better known forays into baseball, football, boxing and ice hockey, George Plimpton also tried his hand at auto racing, playing basketball with the Boston Celtics, soccer with the Tampa Bay Rowdies, tennis with Pancho Gonzales, trapeze acrobatics with the Flying Apollos of the Clyde Beatty-Cole Brothers Circus, stand-up comedy in Las Vegas, as a photographer of Playboy models, and as a percussionist on tour in Canada with the New York Philharmonic orchestra under Leonard Bernstein.

In fact, on his orchestral venture with Bernstein, New York Times reporter Richard Severo would later note: “He was assigned to play sleigh bells, triangle, bass drum and gong, the latter of which he struck so hard during a Tchaikovsky chestnut that Leonard Bernstein, who was trying to conduct the piece, burst into applause.”

Some of Plimpton’s journalism stunts were turned into short television films, including his flying trapeze act, an African wildlife photography stint for Life magazine, and his attempt at stand-up comedy.

He also appeared in bit parts in more than thirty films, including Lawrence of Arabia (Bedouin extra), Rio Lobo (shot by John Wayne), Good Will Hunting (rejected counselor by Matt Damon), and two Ken Burns TV films – Baseball and The Civil War, doing the voice of George Templeton Strong in the latter. And he also did a string of TV commercials and print ads for Intellivision video games in the early 1980s, the income from which he used, in part, to help pay the bills and keep The Paris Review afloat.

But above all, it seems, George Plimpton was a writer. He authored, co-authored, or edited more than 20 books, as well as hundreds of articles for Sports Illustrated, The Paris Review, The New Yorker, Esquire, Harper’s and Horizon magazines, and other publications.

Among his books are titles on Truman Capote and one he edited with author Jean Stein on the 1960s Pop Art scene that featured the rise and fall of Edie Sedgewick, an Andy Warhol star.

An avid birdwatcher, Plimpton also wrote about declining bird populations and threats to bird habitat and rare species, including the ivory-billed woodpecker, whooping crane, and other species. He was also a fireworks enthusiast and wrote a book on that subject.

Plimpton was married twice; first to Freddy Medora Espy in 1968, having two children with her, that marriage ending in 1988. His second marriage was to Sarah Whitehead Dudley, in 1992, having twin daughters with her and remaining in that union through his final days.

George Plimpton died in his sleep on September 25, 2003 in his New York City apartment from an apparent heart attack. He was 76.

Only days before Plimpton had been in Detroit where he and the 1963 Detroit Lions were honored by fans and the Detroit Lions organization at a special “Paper Lion” 40th reunion at Ford Field during a Lions football game.

“George Plimpton was one of a kind,” said Sen. Edward M. Kennedy (D-Mass) in a statement at Plimpton’s death. “He was a lifelong friend of our family since the day he met Bobby at Harvard. . . . He reminded me of the line from Shakespeare, ‘Age could not wither him, nor custom stale his infinite variety.’ We’ll miss him very much.”

Shortly after his death, Cynthia Cotts for the Village Voice, offered a hypothetical “help wanted” ad for a mythical George Plimpton replacement as a lead for her article, “Is George Plimpton Irreplaceable?”:

Wanted: Editor to take over New York-based quarterly magazine of fiction and poetry. Must have impeccable taste, be steeped in the craft of writing and editing, and have met every key literary figure of the last 50 years. Please have natural athletic skills, good manners, and a genuine enthusiasm for life. Be world-famous, witty, unpretentious, admiring of pop stars and complete nobodies, a party animal, experienced fundraiser, and shameless self-promoter. Understand New York as the ultimate coliseum for accomplished people in every field. Optional: be tall, handsome, and well-born, with spacious uptown flat that can double as editorial and business offices and party venue.

In 2008, Graydon Carter, himself a literary figure and editor of Vanity Fair for many years, writing a review for the oral history on Plimpton, George, Being George, would offer this summary:

…As literary lives go, Plimpton’s was a doozy. Well born, well bred, the father of four, a witness to the great, the good and the gifted, he epitomized the ideal of the life well lived. He sparred with prize-fighters and competed against the best tennis, football, hockey and baseball players in the world, and along the way he helped create a new form of “participatory journalism.” He palled around with Norman Mailer, Gore Vidal and William Styron, and drank with Ernest Hemingway and Kenneth Tynan in Havana just after Castro’s revolution. He also edited and nursed that durable and amazing literary quarterly, The Paris Review, which published superb fiction and poetry and featured author interviews that remain essential reading for anyone interested in the unteachable art of writing. ….Plimpton was ….the public face of the New York intellectual: tweedy, eclectic and with a plummy accent he himself described as “Eastern seaboard cosmopolitan.”

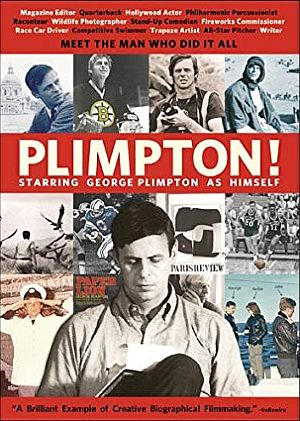

Tom Bean, co-director of the 2014 American Masters/PBS film, Plimpton! Starring George Plimpton as Himself, noted: “George’s life was about seeking out and trying new things, regardless of the outcome. And as an artist, his life was his greatest work of art.”

See also at this website the “Publishing” and “Annals of Sport” pages for additional stories in those categories. Thanks for visiting – and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research and writing at this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

____________________________________

Date Posted: 27 September 2019

Last Update: 25 January 2020

Comments to: jdoyle@pophistorydig.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Paper Lion: George Plimpton,”

PopHistoryDig.com, September 27, 2019.

____________________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

George Plimpton, “Zero of the Lions,” Sports Illustrated, September 7, 1964, pp. 96–117.

George Plimpton, “Hut-Two-Three…Ugh!,” Sports Illustrated, September 14, 1964, pp. 26–35.

Garry Valk, “Letter from the Publisher,” Sports Illustrated, September 13, 1965, p. 4.

“Paper Lion,” Wikipedia.org.

George Plimpton, “The Celestial Hell of the Superfan,” Sports Illustrated, September 13, 1965 pp. 104–120.

George Plimpton, Paper Lion, Harper & Row, 1965.

“Book Review, Paper Lion by George Plimpton,” Kirkus Reviews, 1965.

George Plimpton, “Miami Notebook: Cassius Clay and Malcolm X,” Harper’s, June 1964.

Brian Glanville, “Paper Lion, by George Plimpton,” Commentary Magazine, October 1967.

George Plimpton, “Sportsman of the Year: Bill Russell” and “Reflections in a Diary,” Sports Illustrated, December 23, 1968.

David Remnick, “The Very Good Life Of George Plimpton,” The Washington Post, November 4, 1984.

George Plimpton, Truman Capote: In Which Various Friends, Enemies, Acquaintances and Detractors Recall His Turbulent Career, 1997, New York: Nan A. Talese / Doubleday, 498pp.

Graydon Carter, “Lucky George,” Book Review, New York Times, November 14, 2008

“The Life Adventures of George Plimpton in Trading Cards,” PBS / Thirteen.org.

Luke Poling & Tom Bean (Directors), “Plimpton! Starring George Plimpton As Himself,” American Masters / PBS, May 16, 2014.

Nelson W. Aldrich, Jr., Ed., George, Being George; George Plimpton’s Life as Told, Admired, Deplored, and Envied by 200 Friends, Relatives, Lovers, Acquaintances, Rivals — and a Few Unappreciative Observers, 2008, New York: Random House, 423 pp.

Mike Pesca, “Plimpton’s ‘Paper Lion’ at 40,” NPR.org (audio, Day to Day Show), Septem-ber 22, 2003.

Richard Severo, “George Plimpton, Urbane and Witty Writer, Dies at 76,” New York Times, September 26, 2003.

Patricia Sullivan, “George Plimpton Dies at 76,” Washington Post, September 27, 2003.

David Mehegan, George Plimpton, 76; ‘Paper Lion’ Author, Longtime Literary Editor, Amateur Athlete,” Boston Globe, September 27, 2003.

Eric Homberger, “George Plimpton: Fashionable American Writer Who Founded The Paris Review and Turned Sports Journalism Into an Art Form,” The Guardian, September 29, 2003

Associated Press, “Paper Lions Lose Their Author,” September 26, 2003.

George Kimball, “Plimpton Had No Problem Having Fun,” Irish Times, October 2, 2003.

Terry McDonell, “The Natural: George Plimpton, 1927-2003. A Singular Man of Letters, He Pushed the Limits of Journalism and Helped Define Sport in the 20th Century Even as He Elevated it,” Sports Illustrated, October 6, 2003.

David Remnick, “George Plimpton,” The New Yorker, October 6, 2003.

Cynthia Cotts, “Is George Plimpton Irreplaceable?,” The Village Voice, October 21, 2003.

“George Plimpton, 76; Death Claims Another of My Giants,” BlacklistedJournalist.com, December 1, 2003.

Scott Sherman, “In His League: Being George Plimpton; An Affectionate and Absorbing Oral History Raises Questions of Whether George Plimpton’s Amiable Exterior Concealed a Man Without Qualities,” The Nation.com, January 15, 2009.

Taylor Plimpton, “My Father’s Voice,” The New Yorker, June 16, 2012.

Bill Dow, “Recalling Alex Karras’s Last Public Appearance in Detroit,” VintageDetroit.com, October 11, 2012.

Jessica Gelt, “‘Plimpton!’ Documentary Looks at George Plimpton’s Lives,” Los Angeles Times, June 4, 2013.

Miles Wray, “Review: Out of My League by George Plimpton,” Plougshares at Emerson College, August 28, 2015.

“The Stacks: George Plimpton’s Gridiron Nightmare: In Book After Book, He Was The Everyman Who Donned a Uniform and Played Against the Pros, Never More Appallingly or Hilariously than When He Quarterbacked the Detroit Lions,” The Daily Beast, May 1, 2016.

John Warner, “The Biblioracle: Remembering George Plimpton’s Sports Books,” Chicago Tribune, May 11, 2016.

Nathaniel Rich, “The George Plimpton Story,” New York Review of Books, October 13, 2016.

Paul Brown, “Pitcher, Trapeze Artist, Footballer…”, FourFourTwo.com, March 2018, pp. 96-97.

Bob Morris, “Last Call at George Plimpton’s Party Pad,” New York Times, March 2, 2018.

Little, Brown & Co. Re-issued George Plimpton Sports Books, 2016

George Plimpton, Out of My League: The Classic Account of an Amateur’s Ordeal in Professional Baseball, 2016, Little, Brown & Co., 151 pp.

George Plimpton, Paper Lion: Confessions of a Last-String Quarterback, 2016, Little, Brown & Co., 360 pp.

George Plimpton, The Bogey Man: A Month on The PGA Tour, 2016, Little, Brown & Co., 284 pp.

George Plimpton, Mad Ducks and Bears: Football Revisited, 2016, Little, Brown & Co., 251 pp.

George Plimpton, One for the Record: The Inside Story of Hank Aaron’s Chase for the Home Run Record, 2016, Little, Brown & Co., 193 pp.

George Plimpton, Shadow Box: An Amateur in the Ring, 2016, Little, Brown & Co., 347 pp.

George Plimpton, Open Net: A Professional Amateur in the World of Big-Time Hockey, 2016, Little, Brown & Co., 270 pp.

_________________________