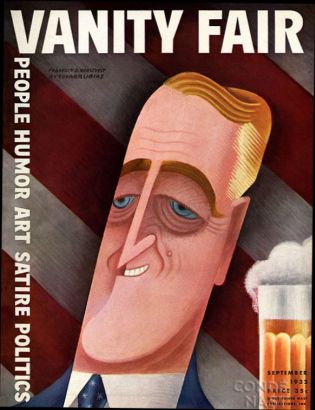

Caricature of NY Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt on the September 1932 cover of ‘Vanity Fair’, by Mexican artist Miguel Covarrubias (artist bio featured later below).

During the fall election campaign that year, Vanity Fair, a magazine of the arts and culture based in New York, put a caricature of Roosevelt on its September 1932 cover, shown at right.

The illustration — by Mexican-American artist Miguel Covarrubias — featured a dapper, blue-eyed and smiling FDR against a background of an American flag’s red and white stripes. This would be the first of about a dozen Vanity Fair covers that would either feature FDR, his New Deal programs as president, or the situation in Washington and nation during the early- and mid-1930s.

Vanity Fair, although primarily a magazine of arts and culture, would use its magazine covers, its artists, and its inside pages to draw attention to Roosevelt’s programs and his time in office through late 1935, when the magazine ceased publishing for at time. A review of some of that coverage — focused primarily on the cover art — follows below, along with a few sketches of the artists involved, cover subject, and the politics of the day.

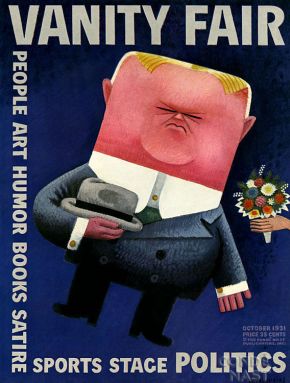

Herbert Hoover was the first political figure on a ‘Vanity Fair’ cover, Oct 1931. Hoover was then blamed for much of the nation’s economic woes, as the Depression arrived on his watch. Here, the artist extends him a bouquet of flowers in appreciation for his moratorium on Germany's reparations payments, which helped protect Europe from financial chaos. (Miguel Covarrubias)

Roosevelt, of course, had more on his mind than Prohibition. He was keenly focused on the nation’s dire economic straits. During his campaigning from July through October of 1932, he promised a program of social reconstruction and federal support of the economy — programs aimed at the “forgotten man.” He stressed the need for an economy that would foster a more balanced distribution of wealth with the least possible federal interference. One of the contributing causes of the Depression, according to some economists at the time, was the concentration of wealth in the stock market and other capital accumulation that was being held back and not being spent or circulated in the wider economy.

FDR’s opponent, the incumbent president, Republican Herbert Hoover — who presided over the stock market crash of 1929 and the onset of the Depression — called for private enterprise solutions, charging that Roosevelt’s program was socialistic. Yet on Hoover’s watch, the Depression had some of its worst years. GNP in 1932 had fallen a record 13.4 percent; unemployment rose to 23.6 percent. Industrial stocks had lost 80 percent of their value since 1930. Some 10,000 banks had failed since 1929, and GNP had fallen a total 31 percent. Over 13 million Americans had lost their jobs since 1929 and international trade was off by two-thirds. Congress had passed the Federal Home Loan Bank Act and the Glass-Steagall Act of 1932, and the nation’s top tax rate had been increased. But public opinion considered Hoover’s measures too little too late. More on the Depression and FDR’s election in a moment. But first some background on Vanity Fair.

Vanity Fair, 1930s

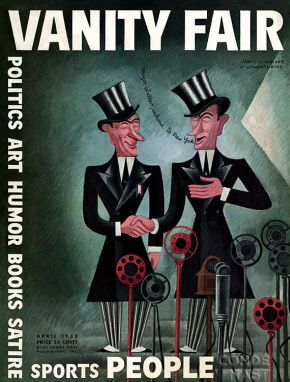

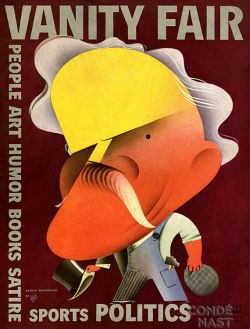

New York mayor Jimmy Walker was the featured caricature on the April 1932 cover of ‘Vanity Fair,” shown here welcoming himself to New York.

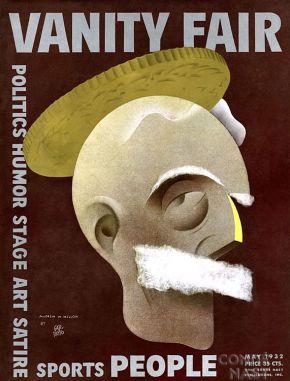

By the mid-1920s Vanity Fair was one of America’s leading culture chroniclers. It contained writing by top writers of the day, including Thomas Wolfe, T. S. Eliot and P. G. Wodehouse, theater criticisms by Dorothy Parker, and photographs by Edward Steichen; Claire Booth Luce was one of its editors for a time. From the fall of 1931, the magazine’s covers ran, in varying order, the words “Art,” People” “Politics” “Satire,” “Sports,” “Humor,” “Books,” “Stage” along one or two of its outer borders (see issues above and below for examples). Politics seemed to gain somewhat more visibility on VF’s covers at about that time, as well. In fact, no political figure had appeared on the cover prior to October 1931, as the magazine’s covers had focused primarily on subjects related to the arts. Herbert Hoover was the first political figure to be caricatured on a Vanity Fair cover — appearing on the October 1931 issue shown above. He was followed by others, including various world leaders: India’s Mahatma Ghandi in November 1931, Britain’s prime minister Ramsay MacDonald in January 1932, and New York Mayor Jimmy Walker in April 1932 (shown above). U.S. Secretary of the Treasury, Andrew Mellon was featured on the May 1932 cover, following his departure from office (see below). Germany’s elderly chancellor Paul von Hindenburg appeared on the cover June 1932; Hindenburg had then narrowly defeated Hitler in a runoff election that April. The magazine also put caricatures of dictators Benito Mussolini of Italy and Adolf Hitler, respectively, on its October and November 1932 covers (shown later below).

The only other Hoover-era official to be featured on a VF cover was Treasury Secretary, Andrew Mellon, in May 1932, shown in white chin beard with coin atop his head. Unpopular at the onset of the Depression, Mellon faced scandal & impeachment with many calling for his removal, forcing Hoover to name him as an ambassador (artist, Paolo Garretto).

A typical Vanity Fair issue in the 1930s had four main sections — “Articles,” included short pieces written on the issues of the day, covering film, books, theater, politics and other subjects; “Short Stories” ran pieces of fiction and nonfiction; “Photographs,” usually a dozen or so large-to-medium sized, featured stage and screen stars and other notables, some of portraiture quality; and finally “Art and Caricature,” featuring paintings by new artists, satirical and comic drawings, and caricatures of celebrities and other notables. Advertising pages were positioned in the front and back of the magazine, running ten to twelve pages in each section, with the magazine’s core content in the middle.

By the 1930s, Vanity Fair was at its peak, with a circulation at just under 90,000 — certainly no threat to the larger circulating Saturday Evening Post, then in the millions-per-week. Vanity Fair’s circulation by 1935 was 88,000, compared to 553,577 at Time, 127,959 at the New Yorker, and 155,476 at Vogue, a sister magazine also owned by Conde’ Nast. Vanity Fair, however, wasn’t after the mass audience; it catered to a more sophisticated readership; one that followed art, film, literature, and to a lesser extent, politics, too — what might today be called the “influentials” or “opinion-makers” market. However, by the mid-1930s, the magazine had fallen out of sync with the times, and would become a casualty of the Great Depression. With the poor economy and the rise of Fascism at the forefront of readers’ minds, subscribers moved to more no-nonsense news coverage. Declining advertising revenues were also a factor, although Conde’ Nast was happy to subsidize this magazine with other revenue. Still, in 1936 Vanity Fair was folded into Conde’ Nast’s Vogue magazine. It would make a comeback in the 1980s. But prior to its first ending — during that early- and mid-1930s time of economic difficulty and political change — Vanity Fair did its share to cover and spotlight politics, with FDR and his programs getting a fair amount of play and artist attention. A further sampling of some of that coverage continues below.

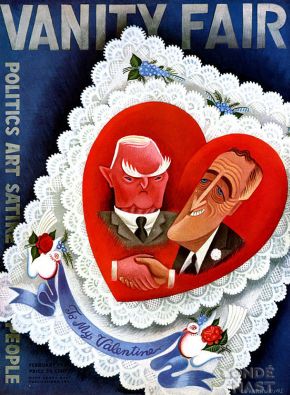

Vanity Fair’s February 1933 ‘valentine’ cover to President-elect Franklin Roosevelt and Vice President-elect, Rep. John Nance Garner, prior to their March 1933 swearing in. (Miguel Covarrubias)

February 1933

Roosevelt Elected

Roosevelt won the 1932 election in a landslide with a popular vote of 22.8 million to Hoover’s 15.7 million. He also swamped Hoover in the electoral vote, 472 to 59. But the new president would not be sworn in until March 1933, as was then the custom. Vanity Fair, meanwhile, offered a Valentine caricature on its February 1933 cover depicting the new president-elect and his former foe, Vice President-elect John Nance Garner, a U.S. Congressman from Texas and then Speaker of the House.

Garner had initially ran against Roosevelt for the Democratic Presidential nomination in 1932, becoming one of Roosevelt’s most serious opponents. When it became evident that Roosevelt would win the nomination, Garner cut a deal with the front-runner, becoming Roosevelt’s Vice Presidential candidate. This cover was another from artist Miguel Covarrubias who by this date had already done a number of caricatures for VF covers, as well as inside pieces (see artist profile below). FDR, meanwhile, had begun his fireside chats on radio as a way to directly communicate with the American people.

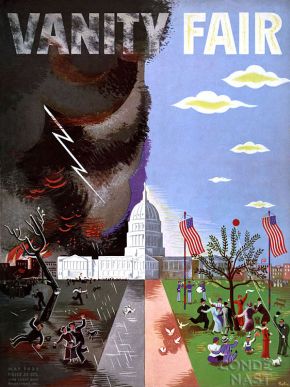

‘Fickle Washington’ – May 1933 ‘Vanity Fair’ cover. Artist: Vladimir Bobritsky.

May 1933

“Fickle Washington”

In the May 1933 edition of Vanity Fair, a cover scene depicting “fickle” Washington, D.C. was offered by artist Vladimir Bobritsky. The cover showed half the scene full of sunshine, blue skies, and flag-flying patriotism, with the other half terrorized by storm clouds and lightening, suggesting the city’s unpredictable and whimsical political nature — patriotic and optimistic one minute, foreboding and disastrous the next. FDR and his Administration at this time were in the middle of their first “100 days” in office, cranking out all manner of new laws in the March-through-June 1933 period to help right the nation’s economic course — from providing relief payments to states, to raising farm prices. Inside this issue of Vanity Fair, meanwhile, there was also an article by writer Jay Franklin, entitled “Not a Cabinet But a Coalition,” describing Roosevelt’s selection of cabinet members.

Among Roosevelt’s main problems when he first took office was the banking crisis. Runs on banks had forced bank failures and official “bank holidays.” Emergency banking powers were among the first laws enacted, giving the government the power to reopen banks once declared secure. Related to the banking and financial issues was gold and gold trading.

June 1933

“Wailing Wall”

The June 1933 cover of ‘Vanity Fair’ offered ‘The Wailing Wall of Gold’ by artist Miguel Covarrubias.

|

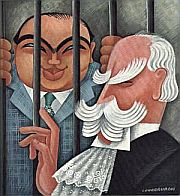

Miguel Covarrubias  Covarrubias at work on a mural, 1939. Photo, Life magazine.  Impossible Interview: Al Capone v. Chief Justice Hughes, 1932. At Vanity Fair, Covarrubias also became noted for the magazine’s “Impossible Interviews” series of caricatures that featured unlikely pairings of public figures from opposing sides of the political and/or social spectrums. Each sketch was accompanied by a short and witty caption or contrived dialogue. The sketches were usually of two famous people unlikely to even be in the same room with one another — i.e., mob boss Al Capone and Chief Justice Charles Hughes; conservative and moralist, U.S. Senator Smith W. Brookhart (R-IA) and movie star Marlene Dietrich; writer Gertrude Stein and comedienne Gracie Allen; movie star Clark Gable and the Prince of Wales; J. D. Rockefeller and Josef Stalin; dancer/stripper Sally Rand with modern dance pioneer Martha Graham; and others.  Benito Mussolini cover by Miguel Covarrubias, Oct 1932. Through his exposure at Vanity Fair, The New Yorker, and other outlets, a great demand for Covarrubias’ art developed. Throughout the 1930s he continued designing covers for Vanity Fair and Vogue. Among others he sketched or caricatured were D.H. Lawrence, Joe Louis, Walt Disney, Benny Goodman, and scenes from the 1943 Broadway musical, Carmen Jones. Covarrubias would later leave Manhattan and return to Mexico, undertaking a study of the anthropology and ethnology of ancient American cultures, while also writing and teaching. He had wide-ranging interests, from archeology and folk art to theater and dance. choreography. He counted among his friends and associates both the Whitney and Rockefeller families, as well as leftist causes and known communists such as Diego Rivera. In 1950, as the U.S. descended into its McCarthyism hysteria, Covarrubias, under scrutiny from the FBI 1943, was labeled a threat to national security. Without visas for U.S. travel, his career took a turn for the worse. He died in 1957 due to complications from ulcers. His art survives today, and is periodically shown in American, Mexican, and other museums. |

Paolo Garretto's rendition of Uncle Sam in the shape of numeral “4” featured on the July 1933 cover of ‘Vanity Fair.’

July 1933

“Despondent Sam”

The July 1933 issue of Vanity Fair featured artist Paolo Garretto’s rendition of Uncle Sam in the shape of an Independence Day numeral “4.” Garretto portrays a despondent Sam, head in hands, seated in the western hemisphere, with storm clouds above. Although a number of FDR’s New Deal programs had been launched, domestically there was little to cheer about, as the economy was dismal.

Overseas, the picture was also dire, with the U.S. set apart from its European allies over international monetary policy. Roosevelt’s rejection of an agreement reached in mid-June at the London Economic Conference resulted in an overwhelmingly negative response from the British and French, as well as inter- nationalists at home. Also in Europe, the Nazis in Germany by this time had already staged massive public book burnings, and had forbidden all non-Nazi political parties.

August 1933

“The Sporting Life”

Vanity Fair’s August 1933 cover focuses on professional athletes of the day, with the exception of FDR on his yacht, bottom center.

Also shown was polo player Tommy Hitchcock, Jr., as polo in the early 1930s was having one of its greatest eras, not only surviving during the Depression, but expanding with a rising number of clubs and recognized national players. Hithcock was one of the latter, known as “a ten-goaler” who for 20 years was an American favorite.

Other notables on this Vanity Fair cover are several boxing athletes, among them, Germany’s Max Schmeling, who was heavyweight champion between 1930 and 1932, shown wearing a swastika. He is flanked by two other smaller boxers, one a Jewish boxer adorned with the Star of David, possibly Barney Ross, a lightweight and welterweight fighter at that time, and on the other side of Schmeling, possibly Jimmy McLarnin, a popular Irish boxer and welterweight champion, shown wearing a shamrock on his sweater. Golf champion Gene Sarazen is also shown.

And finally, though not an athlete, FDR is shown at the bottom of the magazine in a caricature by artist Constantin Alajalov, as a high society yachtsman.

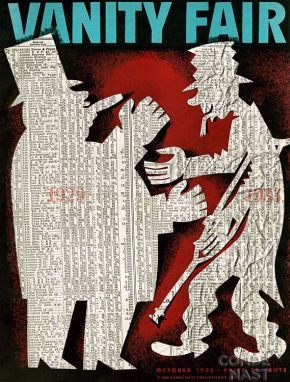

‘Vanity Fair’ cover of October 1933 issue contrasts the ‘Aristocrat’ fat cat of 1929's pre-crash stock market boom, with the ‘down-and-out’ hobo of 1933's Great Depression.

October 1933

Fat Cat & Hobo

The October 1933 issue of Vanity Fair, while not on FDR or the New Deal per see, focused on the contrasting economics of boom and bust in the years 1929 and 1933. Two silhouette characters are featured, shown as cut-outs from newspaper stock market numbers — one shown as a stout, wealthy aristocrat with cigar for the year 1929, pre-crash, and the other, as a down-and-out hobo for the much-deflated realities and hard times of 1933. The two characters portrayed the vast difference between America’s financial attitudes in 1929 and 1933 and the still dire straits that then existed. Roosevelt’s New Deal, meanwhile, unveiled the Civil Works Administration in early November 1933, a government program designed to create jobs through new federal, state, and local projects. Eventually, about $1 billion would be spent on nearly 400,000 projects. Rural America, at that time, was also being ravaged by fierce dust storms. A particularly strong storm on November 11th, 1933 stripped farmland badly in South Dakota — one in a series of disastrous storms that year. Rural America was being hit doubly hard — by natural events bordering on catastrophe plus the Depression. By the end of the year, some 2,000 rural schools would not open for the fall semester and 2.3 million eligible children were not in school. In addition, throughout the nation, a number of colleges and universities were forced to close and some 200,000 teachers were out of work.

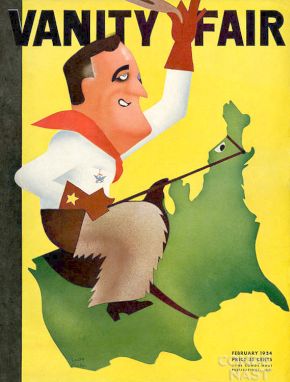

February 1934

FDR to The Rescue?

Cover of Vanity Fair’s February 1934 issue, showing FDR on a ‘rough ride.’

In January 1934, in his message to Congress, FDR had requested $10.5 billion to advance his recovery programs over the next 18 months. In January, Congress also passed the Gold Reserve Act which empowered the president to fix the value of the dollar in terms of its relation to gold, all aimed at giving the Federal government control over fluctuations in the value of the dollar. By late February, Congress would pass the Crop Loan Act to continue programs by the Farm Credit Administration through 1934 to insure that farmers were given loans for crop production and harvesting. More farm programs would follow that spring.

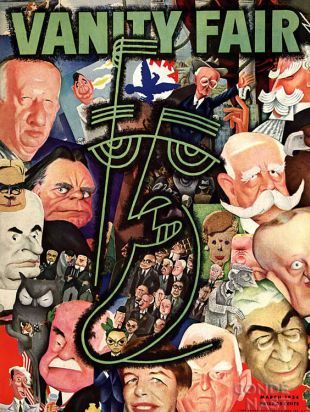

March 1934 cover of ‘Vanity Fair’ showing FDR drawing superimposed over field of political figures of that day.

March 1934

FDR & Politics

In mounting his economic recovery programs, FDR was doing battle on a variety of fronts and dealing with an array of special interests. To give an idea of his political engagement and influence at the end of his first year in office, Vanity Fair’s March 1934 edition offered cover art with a line drawing of the president’s face superimposed over a field of other political and business figures of that time — more tableau than political statement, although FDR friends and foes were both depicted. A number of the caricatured faces came from earlier works by various VF artists, including those of Miguel Covarrubias, Will Cotton, and others. The green line drawing of FDR’s face, though not attributed, could be the work of another artist, possibly Jean Carlu, who had also done cover art for Vanity Fair in the early 1930s.

The New Deal by then was encountering opposition from both ends of the political spectrum. Unions had sparked job actions in various places across the country. A prominent left-wing threat to Roosevelt came from U.S. Senator, Huey P. Long, Democrat of Louisiana, who railed at the New Deal for not doing enough. Long is shown in a smaller Miguel Covarrubias caricature near the top of this cover beneath the “N” in “Vanity Fair.” To the immediate left of Long, in a larger facial caricature, is Al Smith, former New York Governor and 1928 Democratic Presidential candidate. Smith founded the American Liberty League in 1934 to attack New Deal programs as fostering unnecessary “class conflict.” Eleanor Roosevelt — FDR’s wife and sphere of New Deal influence in her own right — is shown on the cover at bottom-center, beneath FDR’s chin, in a drawing by artist Will Cotton.

U.S. Senator William Borah, R-Idaho.

Chief Justice Hughes, from March 1934 VF cover.

Journalist Arthur Brisbane from March 1934 VF cover.

Lippman caricature from March 1934 VF cover.

All of the other faces on the March 1934 cover of Vanity Fair are also those of various political and business figures of that day.

June & Sept 1934

FDR’s “Brain Trusts”

Artist Paolo Garretto gives Washington’s Capitol building a ‘brain trust’ look with scholarly glasses and a mortarboard for the June 1934 cover of Vanity Fair.

Vanity Fair’s September 1934 issue featured FDR’s Brain Trust as an educated eagle with Uncle Sam in its grasp.

By the fall of 1934, a number of government programs that FDR and his administration had created were becoming fair game for journalists and artists. For the September 1934 issues, Paolo Garretto once again caricatured the Brain Trust in a cover scene showing the New Deal era symbol, the NRA eagle, cast in academic black with mortarboard, carrying in its talons, a somewhat watchful Uncle Sam, holding onto his hat. Presumably, this enlightened American thunderbird is taking Sam to a better place, but perhaps not.

In fact, in due time, some of FDR’s Brain Trusters would part ways with him and his policies. Raymond Moley of the first Brain Trust broke with Roosevelt and became a sharp critic of the New Deal from the right. James Warburg also left FDR’s government in 1934, having come to oppose certain policies of the New Deal.

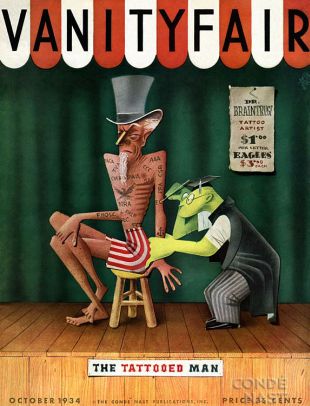

October 1934

“Tattooed Sam”

Vanity Fair of October 1934 featured Uncle Sam as ‘The Tattooed Man,’ bearing all manner of New Deal program and/or government agency acronyms.

Among the programs or agencies tattooed on Sam in this illustration are: AAA, the Agricultural Adjustment Administration, created in 1933 to pay farmers to reduce crop area with the intention of reducing crop surpluses to help raise crop values to restore farm stability; CCC, for the Civilian Conservation Corps of 1933-1942, which employed young men to perform unskilled work, often installing natural resource-conserving improvements in rural areas; NRA (with Eagle on Sam’s chest) was the National Recovery Administration created by the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933 to promote economic recovery by ending wage and price deflation and restoring competition; and the FERA, Federal Emergency Relief Administration, which during the first hundred days of the Roosevelt Administration distributed federal monies to the states to be used to provide work relief or direct relief to households. The FHOLC, or Federal Home Owners Loan Corporation, was created in 1933 to assist in the refinancing of homes. Between 1933 and 1935 one million people received long term loans through this agency that helped save their homes from foreclosure. The Public Works Administration (PWA) was another emergency agency established in 1933, while the Public Buildings Administration (PBA) and the Public Roads Administration (PRA) were prior federal agencies that were rearranged to offer grants to states and cities to build roads and federal buildings outside Washington, D.C. These grants were also used largely to employ workers but also for building public infrastructure and buildings — dams, roads, and schools.

The CSB, or Central Statistical Board, was created in 1933 to coordinate federal and other statistical services. Its duties were later absorbed by the Budget Bureau in 1939. The SAB, also known as The National Research Council’s Science Advisory Board, was created by an executive order issued by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in July 1933 to help address scientific problems of the various government departments, initially to undertake a survey of the overall relationship between science and the government. The FCC, or Federal Communications Commission, was created in 1934 to regulate interstate and foreign communication by telegraph, telephone, cable, and radio. The SEC, or Securities and Exchange Commission, was created in 1934 to protect public and private investors from stock market fraud, deception and insider manipulation on Wall Street.

|

Paolo Garretto  Paolo Garretto, photographed by Lusha Nelson, for the August 1934 issue of Vanity Fair.  A Paolo Garretto caricature of New York Democrat, Al Smith, for ‘Vanity Fair,’ October 1934. |

November 1934

FDR’s “Blue Eagle”

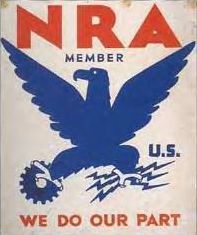

Vanity Fair’s November 1934 issue shows master chef FDR serving up one of his favorite New Deal program symbols: the National Recovery Administration’s Blue Eagle.

The National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA) of June 1933 was one of the famed “first 100 Days” laws enacted in FDR’s first term to deal with the Great Depression. It was enacted to promote economic recovery by ending wage and price deflation and restoring competition. Among other things, the act authorized the President to regulate industry and permit cartels and monopolies in an attempt to stimulate economic recovery. The Act was implemented by the National Recovery Administration (NRA) and the Public Works Administration (PWA), and it authorized the creation and use of industrial codes of fair competition, guaranteed trade union rights, permitted the regulation of working standards, regulated the price of certain refined petroleum products, and authorized public works projects.

‘Blue Eagle’ poster displayed by U.S. companies during 1933-35 that were in compliance with certain New Deal recovery programs.

The Blue Eagle’s days as an official symbol of the NRA and the economic recovery ended by September 1935. However, a part of its legacy survives to this day in the name of the Philadelphia Eagles football team, as in 1933, Philadelphia native and college football coach Bert Bell, who had formed a new National Football League franchise to replace the defunct Philadelphia team named the Frankford Yellow Jackets, named his new team the Eagles in recognition of the NRA.

However, during its two years or so of operation, the NRA issued 557 basic and 189 supplemental industry codes. In addition, some 3,000 administrative orders were issued, running to over 10,000 pages of rules, with thousands of opinions and guidelines from national, regional, and local code boards. Debate over the NIRA’s creation and effectiveness continues to this day, but chief among its failings was its allowance of economically harmful monopolies and its lack of support from the business community, including powerful players such as Detroit automaker, Henry Ford. Franklin Roosevelt, meanwhile, had shifted his views on the best way to achieve economic recovery, and began a new legislative program that would become known as the “Second New Deal” in 1935.

Vanity Fair rang in the 1935 new year with a foldable cover design that revealed a leaner Sam from 1934.

January 1935

The New Year

As the nation rang in its new year of 1935, Vanity Fair’s January issue offered a Miguel Covarrubias caricature of a seemingly robust and pleased Uncle Sam on its cover symbolizing the hoped-for better year ahead. Readers of this issue found instructions on an inside page, that after a series of folds of the cover art, which opened out in two halves, a sad and leaner version of Uncle Same appeared, representing the previous year, 1934, contrasting sharply with the stout and happy figure presented for 1935. By 1935, however, the country had only achieved a modest degree of recovery, with Roosevelt and his Administration under siege by a variety of critics. Still, on January 4, 1935, when FDR delivered his State of the Union message to Congress, he proposed legislation with long-term goals for “social security” — programs for the aged, the unemployed, and the ill. He also called for better housing, taxation reforms and more jobs for the unemployed, and Congress, with its increased Democratic margins, would respond with new programs and more money, helping FDR with what would become known as his “second New Deal.”

Vanity Fair’s March 1935 cover has artist Paolo Garretto depicting FDR as puppet master playing industrialist against the working man as his ‘second New Deal’ offered labor strengthened bargaining rights.

March 1935

Labor Rights

In the spring of 1935, responding to the setbacks in the courts and skepticism throughout the nation, FDR, his Administration, and allies in Congress embarked on their “second New Deal” with initiatives that in some ways were regarded as more radical, more pro-labor, and more anti-business than programs of the first New Deal of 1933-34. Among these was the National Labor Relations Act, also known as the Wagner Act, for Senator Robert Wagner of New York. Following in the wake of earlier initiatives for worker rights and collective bargaining begun in 1933-34 under the NIRA, the Wagner Act would bring more specific law protecting labor organizing. Under the law — debated in Congress during early 1935 and signed by FDR in July that year — employers could not restrain, interfere, with or coerce employees in the exercise of their rights, could not create or support “company unions,” could not discriminate against an employee for union activities, and could not refuse to bargain with a duly designated majority union. Accordingly, Vanity Fair’s March 1935 cover, by Paolo Garretto, had FDR as puppet master, playing industrialist against the working man, also a commentary on FDR’s second New Deal as being more pro labor.

April 1935

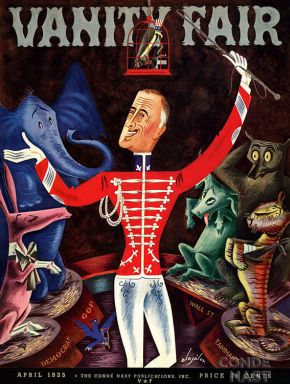

“Ringmaster”

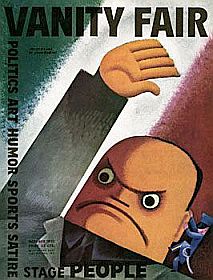

Vanity Fair, April 1935: Franklin Roosevelt shown as confident ringmaster taming all manner of political beasts. Artist, Constantin Aladjálov.

Constantin Aladjálov — the artist who did this cover (b.1900- d.1987) — was a painter and illustrator who studied at the University Petrograd, Russia. His work appeared on the covers of Vanity Fair and other Conde’ Nast publications during the 1930s. Until he arrived in New York in 1924, Aladjálov dabbled in everything from sign painting, to portrait painting, to court painting. He designed covers for The New Yorker from 1926-1960 as well as The Saturday Evening Post. His work also appeared in George Gershwin’s Song Book (1932) and Alice Duer Miller’s Cinderella (1943). Over the years, there have been various national and solo shows of his work in Hollywood, New York, and Dallas. His art is found today in collections at the Brooklyn Museum, Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Modern Museum of Art, and the Dallas Museum of Art.

Back in the New Deal, FDR by 1935 had Democratic majorities in the Congress, and in the spring of that year his Administration charged ahead with more ambitious programs to help the economy. In April, Congress established the Soil Conservation Service in the Department of Agriculture to help stanch the dust storms plaguing the west, and it also authorized nearly $5 billion in relief spending used to set up various programs such as the Works Progress Administration (WPA), established in May 1935. The WPA would become one of the best known New Deal programs, putting millions of Americans to work on various public works projects.

Vanity Fair’s May 1935 issue features a Paolo Garretto caricature of FDR crushing an electric utility executive with his ‘utility reform' Easter Egg.

May 1935

“Utilities”

In the 1920s, electric utility holding companies had consolidated in America to such an extent that by the end of the decade, less than a dozen utility systems controlled three-fourths of the nation’s electric power business. The booming utilities, seen as secure investments in the 1920s, lured in millions of investors, though their pyramidal structures and inflated values were revealed in the 1929 market crash. Attempts at weak regulation followed. FDR fought vehemently against the holding companies, calling them “evil” in his 1935 State-of-the-Union address.

After a hard-fought campaign in Congress, the Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935 was passed. Among other things, the new law required holding companies which owned 10 percent or more of a public utility to register with the Securities and Exchange Commission and report details of their transactions and holdings. The legislation had a dramatic effect on holding companies and over the next two decades their numbers would decline dramatically — from 216 to 18 between 1938 and 1958.

Vanity Fair’s May 1935 issue — in a cover take-off on the annual Easter Egg roll at the White House — featured a caricature by artist Paolo Garretto depicting a grinning Roosevelt pushing a giant Easter egg labeled “Utilities” over a top-hatted electric company executive who is holding a banner that reads “private ownership.”

FDR’s fight for public power became an integral part of his New Deal campaign. In addition to the utilities bill, Congress also passed the Federal Power Act of 1935, which gave the Federal Power Commission regulatory power over interstate transmission and wholesale transactions of electric power. The Federal Power Act also gave the FPC the legal power ensure that electricity rates were “reasonable, nondiscriminatory and just to the consumer.” And adding to this public power initiative, and that of the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) already created in 1933, Roosevelt by executive order in May 1935 authorized the U.S. Rural Electrification Administration (REA) to create and finance rural utility companies to serve farmers and rural Americans all across the country.

Demise of Vanity Fair

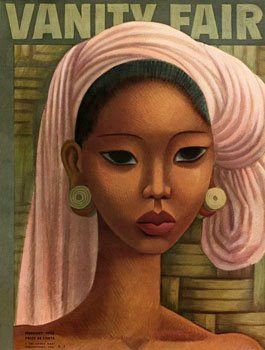

Miguel Covarrubias' illustration, 'Bali Beauty,' for the February 1936 issue of Vanity Fair, marked the last issue of the magazine that had used its covers to spotlight FDR & the New Deal.

Lack of advertising revenue, the continuing Depression, and the changing times helped to hasten the end of Vanity Fair, which was folded into Vogue, another Conde’ Nast publication. Vanity Fair had seen some of its best years in terms of sales in 1931 and 1935, and it continued to attract new readers in that period. Vanity Fair had become more political during the Depression than it ever had been before, bringing along some of its previously non-political sophisticates into an at least appreciative following of politics. Vanity Fair’s readership, according to some, even though it showed signs of growth, no longer had the market value it once did: its readers weren’t buying the advertised products. It was also considered a bit too urbane for those times. So it ceased publication. But it would rise again, in a new form, in the 1980s.

As for FDR and the New Deal, had Vanity Fair lasted through the later terms of his presidency, and the controversies that swirled around them, there is no telling what turns the cover art may have taken — but it is likely that good caricature and satire would have continued in fair display. Happily, in its modern rebirth since 1983, Vanity Fair has renewed and continued the creative blending of art, satire, and politics to good effect, though there still may be some pining for that old-form, art caricature that can grab readers’ attention in unique ways and leave lasting impressions.

Readers of this story may also find others on similar topics at the “Politics & Culture” category page and/or the “Print & Publishing” page. See also “Magazine History,” a topics page with links to additional stories in that category. Thanks for visiting – and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research and writing at this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

___________________________________

Date Posted: 2 November 2009

Last Update: 10 June 2021

Comments to: jdoyle@pophistorydig.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “FDR & Vanity Fair, 1930s,” Pop

HistoryDig.com, November 2, 2009.

___________________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

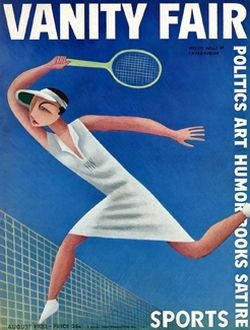

Another sample of Vanity Fair cover art from January 1932 – Paolo Garretto depicts the changing allegiances of Ramsay MacDonald, then Britain's prime minister, by dressing him in worker's overalls on one side and an aristocrat's suit and top hat on the other. |

Miguel Covarrubias’ cover for Vanity Fair’s August 1932 issue featured tennis star Helen Wills Moody. |

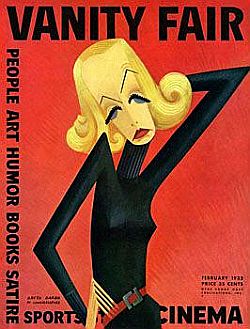

Miguel Covarrubias’ caricature of Greta Garbo appeared on the February 1932 cover of Vanity Fair. |

Paolo Garretto casts Adolf Hitler in political cartoon for Vanity Fair’s November 1932 cover. |

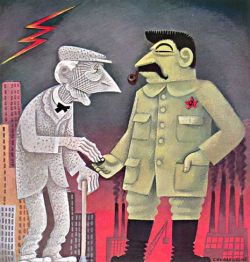

John D. Rockefeller & Joseph Stalin, ‘Impossible Interviews,’ Vanity Fair, April 1932. |

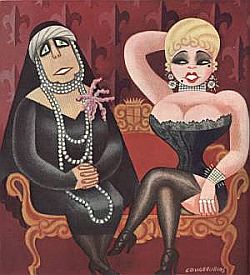

Queen Marie & Mae West, ‘Impossible Interview,’ June 1932, Vanity Fair |

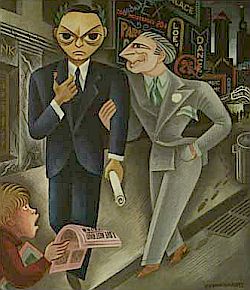

Lippmann & Walter Winchell, ‘Impossible Interviews,’ Vanity Fair, 1930s. Miguel Covarrubias. |

David Friend, “Vanity Fair: The One-Click History,” VanityFair.com, 2008.

Amy Fine Collins, “Vanity Fair: The Early Years, 1914-1936,” VanityFair.com, 2008

Susan Ronald, Condé Nast: The Man and His Empire – A Biography, 2019, St. Martin’s Press, 448 pp. Click for copy.

Cleveland Amory and Frederic Bradlee, Vanity Fair: A Cavalcade of the 1920s and 1930s. The Best Stories, Articles, Humor, Photographs, Art from America’s Most Memorable Magazine, 1960, Viking Press, 327 pp. Click for copy.

Graydon Carter with David Friend, Bohemians, Bootleggers, Flappers & Swells: The Best of Early Vanity Fair, 2014, Penguin Press. Click for copy.

Graydon Carter, David Friend, Vanity Fair: The Portraits: A Century of Iconic Images, 2008, Abrams, 384 pp. Click for copy.

“Vanity Fair,” The American Studies 1930s Project, English Department, University of Virginia, site accessed, October 2009.

David Friend, “The 1930s and Vanity Fair,” VanityFair.com, June 11, 2008.

Kitty Hoffman, “A History of Vanity Fair; A Modernist Journal in America.” Dissertation, University of Toronto, Canada,1980.

Walter Lippman, “Post Mortem: The Election,” Vanity Fair, January 1929.

“West Will Launch Roosevelt Boom; State of Washington Expected to Put Him Before Nation for Presidency Feb. 6,” New York Times, Tuesday, January 5, 1932, p. 8.

Jay Franklin, “New Years Day and Mr. Hoover,” Vanity Fair, January 1933.

Marcus Duffeld, “Brightening Up Politics,” Vanity Fair, January 1933.

“Roosevelt Orders 4-Day Bank Holiday, Puts Embargo on Gold, Calls Congress,” New York Times, March 6, 1933.

“President and Wife Call on Mr. Holmes; Felicitate the Former Supreme Court Justice on His Ninety-Second Birthday,” New York Times, Thursday, March 9, 1933, Section, Social News, p. 17.

Jay Franklin, “Not a Cabinet But a Coalition,” Vanity Fair, May 1933.

“The New Deal,” Wikipedia.com

David A. Horowitz, “Senator Borah’s Crusade to Save Small Business From the New Deal,” The Historian, June 22, 1993.

“Walter Lippmann,” The Columbia Encyclopedia, sixth edition, Encyclopedia.com, 2008.

Johnna Rizzo, “Covarrubias’ Early Days in New York,” Humanities, May/June 2006.

Edward Sorel, “Covarrubias,” American Heritage Magazine, Vol. 45, Issue #8, December 1995.

“Miguel Covarrubias,” Wikipedia.com.

Kurt Heinzelman (ed), The Covarrubias Circle: Nickolas Muray’s Collection of Twentieth-Century Mexican Art, University of Texas Press, 2004.

“Illustration: The Genius of Miguel Covarrubias,” AnimationArchive.org, Monday, May 14, 2007.

Henry C. Pitz, “Miguel Covarrubias of Mexico City,” American Artist, January 1948, pp 21-24.

Samples of Miguel Covarrubias artwork, American Art Archives.

________________________________

Miguel Covarrubias, “Impossible Interviews”

(samples follow below)

“Marie of Romania vs. Mae West,” text by Corey Ford, Vanity Fair, June 1932. The Romanian Queen laments her neglect by the public, to which West replies: “What I mean, sister, lemme put you wise. Royalty don’t get you any place, any more. Today they only want the kind of a Queen they can hold on their laps. Lookit me, for instance. Every other inch a Queen, from hips to whoozis.” (see image, below right)

“John D. Rockefeller Sr. vs. Joseph Stalin,” Vanity Fair, April 1932.

“Senator Smith W. Brookhart vs. Marlene Dietrich, Vanity Fair, September 1932.

“S.L. Rothafel vs. Arturo Toscanini,” Vanity Fair, February 1933.

“Herr Adolf Hitler and Huey ‘Hooey’ Long vs. Joseph Stalin and Benito Mussolini,”Vanity Fair, June 1933.

“Sally Rand (dancer/stripper) vs. modern dance pioneer, Martha Graham,” Vanity Fair, December 1934, text by Cory Ford. In the accompanying mock dialogue, stripper Sally is quoted as saying they were “…just a couple of little girls trying to wriggle along.”

“Freud vs. Jean Harlow,” Vanity Fair, May 1935.

George Arliss vs. Cardinal Richelieu, Duke of Wellington, and Disraeli,” Vanity Fair, January 1936.

___________________________

Mike Rhode, “Miguel Covarrubias Portraits on Display This Fall” (with earlier review), ComicsDC, Thursday, August 30, 2007.

Steven Heller, “Paolo Garretto: A Reconsider- ation,” undated paper (PDF) with sample Paolo Garretto works, 13pp.

“Paolo Garretto Is Dead; Italian Caricaturist, 86,” New York Times, Tuesday, August 8, 1989.

Sampling of Paolo Garretto caricatures at Cartan- tica.It.

Steven Heller, Design Literacy: Understanding Graphic Design, Allworth Press, 2004, 433pp.

Price Fishback, Professor of Economics, University of Arizona, New Deal 2 Editor, “Impact of New Deal Programs on Welfare,” Analysis Online.Org.

Price V. Fishback, William C. Horrace and Shawn Kantor, “Did New Deal Grant Programs Stimulate Local Economies? A Study of Federal Grants and Retail Sales During the Great Depression,” Journal of Economic History, March 2005.

Fishback, Price V., William C. Horrace, and Shawn Kantor, “The Impact of New Deal Expenditures on Mobility During the Great Depression,” Explorations in Economic History, 43 (April 2006), 179-222.

Alex J. Pollock, “A 1930s Loan Rescue Lesson,” Washington Post, Friday, March 14, 2008

National Labor Relations Board, The First 60 Years — The Story of the National Labor Relations Board: 1935-1995, American Bar Association, 1995.

Cabell B. H. Phillips, From the Crash to the Blitz, 1929-1939, Fordham University Press, 596pp.

PBS, “Regulation: Public vs. Private Power: From FDR to Today,” Frontline, Program: “Blackout: What Caused the Power Blackout in California? And Who’s Profiting?,” A co-production of Frontline and The New York Times, June 2001.

See Vanity Fair Store to purchase prints of vintage Vanity Fair magazine covers from the 1930s and other time periods.