On January 17th, 2015, as much as 1,200 barrels of crude oil may have leaked into Montana’s Yellowstone River.

The Poplar line is one of those that transports crude oil from the newly-productive Bakken oil fields of eastern Montana and western North Dakota. “The Bakken,” as it is known in the trade, is an historic area of large oil reserves that has seen renewed booming development with new hydraulic fracturing technology, also known as “fracking.” The Poplar line runs from the Canadian border to Baker, Montana, where it meets the Butte pipeline, also owned by Bridger.

According to initial reports, the spill occurred some nine miles upstream from Glendive, an agricultural town of about 6,000 people located near the North Dakota border and about 220 miles northeast of Billings, Montana. Once the leak was discovered early aircraft patrols spotted an oily sheen on the Yellowstone some 25 miles downstream from the leak. An Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) official later said an oil sheen was also detected near Sidney, Montana, about 60 miles downstream, although icy conditions generally made detection and attempted clean-up difficult.

January 23, 2015: Aerial photo looking down on ice-covered Yellowstone River as workers attempt to find and clean up an oil spill that occurred on January 17, 2015 near Glendive, MT from the Poplar Pipeline. EPA Photo.

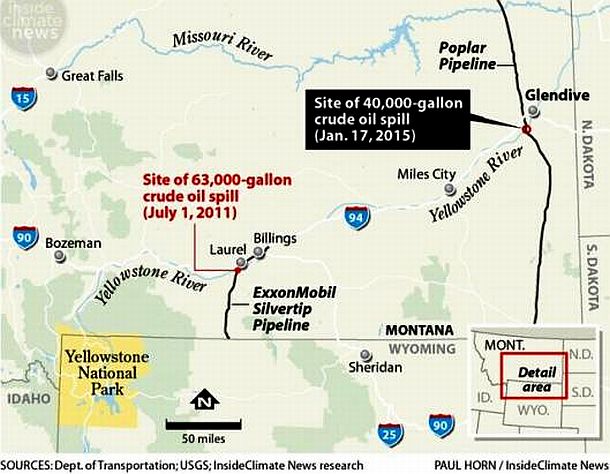

The Yellowstone River, which has it headwaters in the Rocky Mountains of Wyoming and Yellowstone National Park (see map below), flows north into Montana and then east and northeast across the state and eventually, several hundred miles later, northeast into North Dakota where it flows into the Missouri River.

ExxonMobil/Silvertip Spill. The Bridger Pipeline oil spill into the Yellowstone River was the second recent pipeline breach releasing oil into the Yellowstone in less than four years. In July 2011, ExxonMobil Corp’s 40,000 barrels-per-day Silvertip pipeline in Montana ruptured beneath the river near Laurel, Montana, about 230 miles southwest of Glendive. That rupture released an estimated 1,500 barrels (63,000 gallons) of crude into Yellowstone River that washed up along some 85 miles of riverbank, costing the company about $135 million to clean up. Federal regulators later levied a $1.7 million penalty against ExxonMobil for that incident and the government is still in the process of pursuing the company for natural resources damages for the spill.

This map, compiled by Inside Climate News, shows the locations of both the July 2011 ExxonMobil pipeline spill and the January 2015 Poplar Pipeline spill, both fouling the Yellowstone River. Click on map for Inside Climate News.

“This is a significant spill,” the EPA said in a January 19th, 2015 statement regarding the Bridger/Poplar pipeline breach. The oil “threatens downstream water users, including drinking water supplies, agricultural uses, and wildlife,” the agency stated. EPA was then working with Bridger, local and state officials as well as the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the U.S. Department of Transportation to contain the spill. Dave Parker, a spokesman for Montana Governor Steve Bullock, said on January 19th: “We think it was caught pretty quick, and it was shut down. The governor is committed to making sure the river is cleaned up.” Bridger Pipeline Co. issued a statement saying the pipeline was shut down shortly before 11 a.m. Saturday. Spill responders by then began placing containment structures across the Yellowstone River at Sidney, Montana, about 30 miles downstream of the spill.

Airboats were being used to transport oil spill response workers on the frozen Yellowstone River following the break of the Poplar Pipeline near Glendive, MT. Some of the early response shown here. Photo, Great Falls Tribune.

Complicating the tracking and clean up of the spill was the fact that the river was partially frozen, much of it covered in ice as shown in the photos above. By January 19th, 2015, two days after the leak was discovered, cleanup workers had cut holes into the ice on the Yellowstone River near Crane, Montana as part of efforts to recover oil from the upstream leak. “These are horrible working conditions to try to recover oil,” Paul Peronard, the EPA’s on-scene coordinator, said at one point. “Normally you at least see it, but you can’t see it, you can’t smell it, ” he said. “We’re going to have to hunt and peck through ice to get it out.” By Tuesday, January 20th, oil sheens were reported as far away as Williston, North Dakota, below the Yellowstone’s confluence with the Missouri River. By February 4th, however, clean-up efforts along the Yellowstone were suspended due to weather conditions.

Jan 20, 2015: Residents of Glendive, MT line up to receive drinking water at distribution center. Matthew Brown / AP |

Jan 21, 2015: EPA contractor Megan Adamczyk examining water sample from a Glendive fire hydrant. |

Jan 20, 2015: Whitney Schipman of Glendive, MT receives a case of bottled drinking water. AP Photo/Matthew Brown |

January 2015: Residents of the Glendive area loading bottled water into their car. |

Drinking Water

One immediate worry in the wake of the spill was the safety of drinking water in Glendive and other towns downstream that depend on the river for drinking water. Initial water tests in Glendive Saturday and Sunday showed no evidence of oil, but residents soon complained that their tap water had an unusual odor. An advisory against using the water was issued late Monday, January 19th by offficials at the city’s treatment plant. Truckloads of bottled drinking water were shipped into Glendive as residents began lining up. Some businesses dependent on water, such as restaurants, shut down for a time.

It was later reported that benzene in the range of 10 to 15 parts per billion was detected in some early samples of Glendive water, according to EPA’s Paul Peronard. Anything above 5 parts per billion is considered a long-term risk, but not likely a health risk over a short period of time.

On the benzene problem, it was first thought that since oil floats, it would be well above the Glendive water treatment plant intake, which is some 14 feet deep in the river. However, the river was covered by ice. One theory offered was that because the oil was trapped beneath the ice rather than in the open air, chemical constituents such as benzene, could not volatilize into the air, and instead became dissolved throughout the entire water column. Some oil was also moving downstream.

On January 22nd, EPA investigated a reported contaminant at the water intake for city of Williston, ND suspected as being related to the Bridger Pipeline release. The reported contaminant level was subsequently found to be well below the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) standards.

Back at Glendive meanwhile, by Friday, January 23, 2015, the municipal water supply was given the O.K., as it was then meeting standards set by the federal Safe Drinking Water Act, according to Montana’s Department of Environmental Quality. Bottled water distribution in Glendive was also discontinued at that time since city’s water was certified safe to drink. As a precaution, local authorities stockpiled a two-day supply of bottled water in Glendive.

By February 3rd, 2015, Bridger opened a claims center in Glendive for people affected by the spill. “…[W]e have the claim center set up, so businesses, residents and even local governments that have incurred added expense, because of this incident, which we’ve taken responsibility for, that we can reimburse them for those expenses,” said Bridger’s Bill Salvin.

|

“A Much-Loved River”  The Yellowstone River as viewed in Yellowstone National Park at the tamer northern end of the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone River. …When the West was won, most rivers were lost to damming and dewatering. This river is the exception: it remained wet, wild and dam-free over its entire length. The Yellowstone flows free for over 650 miles, draining a watershed greater in area than all of the New England states combined. In the 1970s, Montanans held a great debate over this mighty river’s future. When the dust settled, the state reserved a Yellowstone might never be depleted and might forever remain free-flowing. Other uses of the river-municipal: agricultural and industrial are also provided for. Today this waterway is in balance with all its users, including nature’s creatures. Few American rivers can still make that claim.  The Yellowstone River in Montana. |

Other Issues

Judy Woodruff, of the “PBS NewsHour,” reporting on the Glendive, Montana oil spill, January 2015.

Bridger Pipeline LLC logo. |

Belle Fourche Pipeline Co. logo. |

Company Record. The owner of the Bridger Pipeline Company, True Oil LLC, a family-owned company, also owns other pipelines, and a second pipeline company, Belle Fourche, which operates lines and tanks across some 551 miles in Montana, North Dakota and Wyoming. According to the Casper Star-Tribune, both companies have had prior spills, together accounting for some 30 incidents in Montana, North Dakota and Wyoming between 2006 and 2014. The Bridger Company reported nine incidents to government authorities during that time frame, while Belle Fourche, reported 21. Some of True Oil’s pipeline companies also own and operate “gathering lines” in the oilfields, small-diameter lines which gather oil from wells. These lines are unregulated and often a source of oilfield leaks and spills that go unreported and unmitigated.

Ecology & Wildlife. Environmental authorities say the ice cover on the river will delay the evaluation of the spill’s impact on fish and wildlife, probably until spring. The area provides nesting habitat for bald eagles and the river is also home to the pallid sturgeon, an endangered species. State and federal wildlife officials have identified nesting locations to be avoided during cleanup, especially during the spring breeding season. Bald eagles, piping plovers, and interior least terns are in the area, as are heron. Bald eagles will abandon their nests and chicks if their nests are disturbed. There will likely be some fish impact as well; oil spill toxins can accumulate in fish tissue as well as in the worms and crawdads that fish eat. Oil can also harm the tiny fibers in fish gills, their “breathing” system.

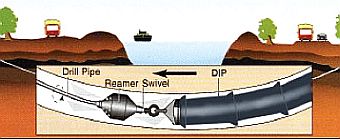

Artist’s rendering of pipeline tunneling beneath a riverbed.

Bigger Picture

Beyond the Bridger Pipeline spill itself, is the larger issue of pipeline water crossings generally – existing and proposed. Among the latter category is the hotly debated Keystone XL oil pipeline, a line that would cross nearly 1,900 rivers, streams and reservoirs in Montana, South Dakota and Nebraska, according to one estimate. The route also takes that proposed pipeline across the Missouri and Yellowstone rivers in Montana, where owner TransCanada has pledged to install the pipeline 35 feet below the riverbeds.

The proposed Keystone XL pipeline, carrying Canadian tar sands crude, will cross the Missouri and Yellowstone rivers.

Another problem with regard to pipelines nationally is a lack of frequent inspections, fueled in part by too few inspectors. Shortly after the Bridger/Poplar pipeline spill near Glendive, U.S. Sen. Jon Tester (D-Mont.), offered an amendment to the Keystone XL pipeline bill – then being considered in the U.S. Senate. Tester’s amendment called for a study of the federal pipeline agency’s inspection program. He argued that more inspectors were needed to prevent accidents like the one in Glendive. However, his amendment was never voted on, but the Keystone measure itself – which President Obama was then vowing to veto – was approved by the Senate.

|

“The Daily Damage” This article is one in an occasional series of stories at this website that feature the ongoing environmental and societal impacts of industrial spills, toxic releases, fires, air & water pollution incidents and other such occurrences. These stories will cover both recent incidents and those from history that have left a mark either nationally or locally; have generated controversy in some way; brought about governmental inquiries or political activity; and generally have taken a toll on the environment, worker health and safety, and/or local communities. My purpose for including such stories here is simply to drive home the continuing and chronic nature of these occurrences through history, and hopefully contribute to public education about them so that improvements will be made in law, regulation, and industry practice, and that safer alternatives will replace them in the future. — Jack Doyle |

However, on February 13th, 2015, Montana’s Governor, Steven Bullock (D) wrote to the Obama Administration urging a review of the current four-foot depth requirement for pipeline crossings beneath major waterways. Bullock also asked for more federal pipeline inspectors in Montana, which currently has only one overseeing some 3,800 miles of pipelines in the state. “Clearly, more frequent inspections and oversight are needed so as to avoid another major disaster here in Montana,” Bullock wrote.

Meanwhile, American Rivers, a Washington-based conservation organization working to protect the nation’s rivers, initiated an online petition drive shortly after the Poplar Pipeline spill, urging citizens to send a message to the federal pipeline agency, PHMSA, “to strengthen standards for oil pipelines and better protect our clean water.” At its petition site, American Rivers explains that “since 1986, pipeline oil spills have caused more than 55 deaths, 2,500 injuries, and more than $7.7 billion in damages.” The recent Yellowstone spills, says American Rivers, are “the latest in a string of pipeline failures that have put our rivers and clean water at risk.”

In the end, the Glendive/Poplar Pipeline oil spill may prove to have modest impacts, especially when compared to catastrophic spills such as the 2010 BP blow-out in the Gulf of Mexico. Still, the final verdict and full assessment for the Glendive/Poplar spill is some months away. Even if it turns out to be a modest incident, it is nevertheless one more in the continuing fossil fuels assault – i.e., spills, explosions, fires, toxic releases, and greenhouse gases – that have been occurring regularly for the past century or more. Clearly, there are safer energy alternatives available that should become the preferred choices of policy makers and political leaders everywhere.

Stay tuned to this website for future stories on environmental history and “the daily damage.” See, for example “Burn On, Big River,” a story about the history of pollution-caused Cuyahoga River fires in Ohio; “Paradise,” a story about Kentucky strip mining and the demise of a small town there; or “Power in the Pen,” about Rachel Carson’s powerful indictment of chemical pesticides in her famous book, Silent Spring. Thanks for visiting — and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research and writing at this website. Thank you. — Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

____________________________________

Date Posted: 15 February 2015

Last Update: 1 July 2019

Comments to: jdoyle@pophistorydig.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “”Oil Fouls Montana: January 2015,”

PopHistoryDig.com, February 15, 2015.

____________________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

Workers attempting early clean-up on the frozen Yellowstone River cutting 75-foot long “ice-slots” into the river(right, continuing out of frame) to try to collect passing oil spill (see below). |

Long, three-foot wide ice slots, cut in the river ice with chain saws and fitted with absorbent material, were tried in early clean-up attempts following the Poplar Pipeline spill near Glendive, Montana. |

Oil spill crew in air boat on icy Yellowstone River have safety line tied to worker trying to soak up oil, January 2015. |

“Bridger Pipeline’s Oil Spill on the Yellow- stone River Near Glendive,” Montana.Gov, January February, 2015.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, “Bridger Pipeline Release,” Incident Website, January-February 2015.

Associated Press, “Cleanup After ‘Unfor- tunate Incident’ in Yellowstone,” CBSNews .com, January 19, 2015.

Associated Press, “Oil Spill Forces Drinking Water to Be Trucked into Montana Town,” FoxNews.com, January 20, 2015.

Wendy Koch, “Oil Spills Into Yellowstone River, Possibly Polluting Drinking Water,” National Geographic, January 20, 2015.

CBS/AP, “Yellowstone River Spill: Oil Detected in Water Supplies,” CBSNews.com, January 20, 2015.

Eric Killelea and Jack Healyjan, “Traces of Montana Oil Spill Are Found in Drinking Water,” New York Times, January 20, 2015.

CBS/ Associated Press, “‘It’s Scary:’ City Rushes to Rid Water of Cancer-Causing Agent After Oil Spill,” CBSNews.com, January 21, 2015.

Elizabeth Douglass, “Ruptured Yellowstone Oil Pipeline Was Built With Faulty Welding in 1950s…,” InsideClimate News, January 22, 2015.

Matthew Brown, (AP), “Regulators Order Pipeline Upgrades after Montana Oil Spill,” YahooNews, January 23, 2015.

Editorial, “Lessons Learned From Montana’s Oil Spills,” Billings Gazette, January 27, 2015.

Greg Seitz, “Oil & Water: Pipeline Safety Questioned from Montana to Southern Wisconsin,” St. Croix 360, MinnPost.com, January 29, 2015.

Benjamine Storrow, “Oil Spill Near Glendive Latest in String of Casper Company’s Pipeline Breaks,” Casper Star-Tribune, February 2, 2015.

Brett French, AP (Billings, MT), “Labs Testing Yellowstone River Fish after Oil Spill,” February 2, 2015.

Karl Puckett, “Impacts of Oil Spill on Fish, Birds Still Unknown,” GreatFallsTribune .com, February 2, 2015.

Simone DeAlba, MTN News, “Ice Halts Oil Spill Cleanup Efforts on Yellowstone River,” KXLH.com, February 4, 2015.

Elizabeth Douglass, “Yellowstone Oil Spills Expose Threat to Pipelines Under Rivers Nationwide,” InsideClimate News, February 6, 2015.

True Oil, LLC, “Companies,” TrueCos.com, Casper, Wyoming.

National Wildlife Federation, “Assault on America: A Decade of Petroleum Company Disaster, Pollution, and Profit,” NWF.org, July 28, 2010.

Karl Puckett, “Oil Spill Caught Montana City off Guard,” GreatFallsTribune.com, February 10, 2015.

_________________________________