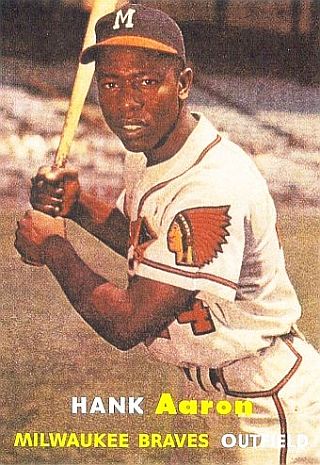

Topps baseball card for Hank Aaron in 1957, one of his best years, hitting 44 home runs, leading the Braves to the NL pennant and World Series title over the NY Yankees, and taking the National League MVP award. He was then 23 years old.

In this photo, however, what is most interesting is the face of the young Henry Aaron.

It is a face that is open, honest, and non-threatening; a face of someone who bears no ill will; a face of a determined ball player with still boyish dreams.

It is also the face of a good and decent man; a man whose life and baseball career would validate that view. More on that to come in the story that follows.

Yet there came a mean season in the life of Henry Aaron the baseball player; a mean season that hurt him deeply at the apex of his prodigious career, precisely when he should have been enjoying his hard-won fame and record-setting accomplishments.

But what came instead, was an ugly chapter of American racism that would forever scar the hopeful Alabama boy who had put his heart and soul into baseball.

During 1973-74, Henry Aaron had to be protected by private guards. On the road, at away games, he couldn’t stay at the same hotel as his teammates. His family was in danger too. Kidnaping threats were made on his daughter at college.

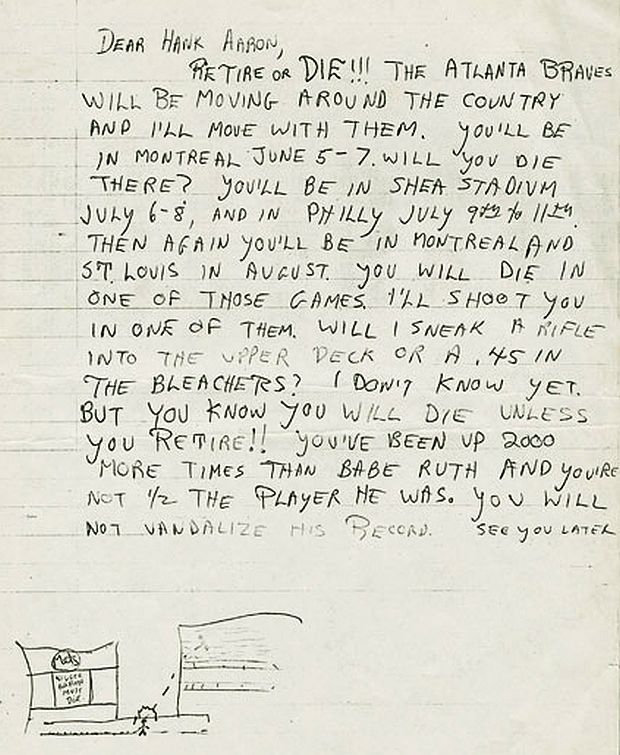

Then there was the hate mail.

Thousands of letters came with all manner of racial slurs and threats – one with a little hand-written diagram of a rifle-shot trajectory from the bleachers aimed at killing him. But Hank Aaron was only trying to play baseball.

It happened at the time that this very good ballplayer – who by then had played some 20 years in professional baseball with distinction – was closing in on one of the game’s most hallowed and revered records: Babe Ruth’s career home run mark of 714.

Ruth’s home run record had stood for 39 years, since May 25, 1935, when the Babe hit his last three homers in Pittsburgh. In fact the Ruth record had stood so long that there was no real thought it would ever be broken. But Henry Aaron had crept up on the record with his workman-like consistency, hitting 30 or more homers a year for much of his career. Yet Ruth diehards, and more obnoxiously – vehement racists – went after Aaron when it appeared he would soon catch and likely surpass Ruth. Yet Henry Aaron was doing what he had always done since a young boy; playing baseball.

Artist rendition of Hank Aaron in 1952 when he played briefly with the Indianapolis Clowns of the professional American Negro League, by Graig Kreindler (2017).

Early Days

Henry Louis Aaron was born in February 1934 in the black section of Mobile, Alabama known as “Down the Bay.” He was the third of the eight children born to Herbert and Estella Aaron. Herbert worked as an assistant to a boilermaker on the Mobile drydocks and also owned a small tavern. Growing up in the segregated south, Henry would later recall his mother telling him as a young boy to hide under the bed as the KKK came through their neighborhood. When Henry was eight years old, the family moved to Toulminville, a more middle-class neighborhood.

Not much for school, though he could be a decent student when interested according to his mother, Aaron had baseball in mind from his youngest days, playing with bottle caps and broomsticks.

After he heard Brooklyn Dodgers’ Jackie Robinson talk when Robinson visited Mobile in 1948 for an exhibition game, young Henry set his sights on baseball. Robinson had only a year earlier broken the color barrier in professional baseball.

Aaron had attended Mobile’s segregated Central High School as a freshman and sophomore, and then went to the Josephine Allen Institute, a private school. There, the emphasis was on football, and Aaron played halfback and end. And although good enough to draw college scholarship offers, he didn’t especially like football. Some reports say he also played on the schools’ softball team and as a younger boy had also played in neighborhood ballparks.

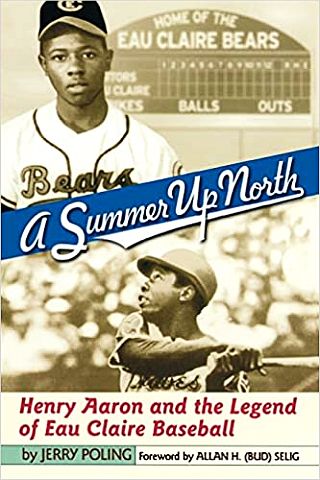

Jerry Poling’s 2002 book on Hank Aaron’s first Minor League season in Eau Claire, WI, with foreword by Bud Selig. Click for copy.

(Another story about Aaron’s discovery by Ed Scott came during a neighborhood softball game, when Aaron was seen lacing line drives off the outfield fence. “I was like, ‘Look at those wrists,” recalled Scott. “Why isn’t he playing baseball?'”)

In 26 games in the Negro League, Aaron hit an estimated .366 with five home runs and 33 RBIs. By 1952 he caught the eye of major league scouts for the New York Giants and the Boston Braves (later to become the Milwaukee Braves in 1954, and Atlanta Braves in 1966).

A May 26, 1952 Boston Braves scouting report by Dewey S. Griggs on the 17 year-old Aaron as he played with the Indianapolis Clowns, noted : “great pair of hands, seems relaxed at all times, and a good wrist hitter.” Griggs recommended him as a “definite” prospect.

A May 27th, 1952 letter from Syd Pollock, the owner of the Indianapolis Clowns to Braves executive John Mullen, then concerning the terms of Aaron’s contract and sale to the Braves, noted: “I feel this youngster is another Ted Williams in the hitting department, and can hit to all fields, as well as lay down bunts…”

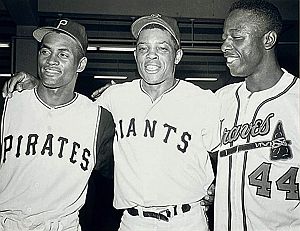

Aaron, in fact, had received two offers from Major League baseball teams via telegram, one from the New York Giants and the other from the Boston Braves. Years later, Aaron would note: “I had the Giants’ contract in my hand. But the Braves offered fifty dollars a month more. That’s the only thing that kept Willie Mays and me from being teammates – fifty dollars.”

The Braves paid the Indianapolis Clowns $10,000 for Aaron’s contract, and that summer of 1952 Henry Aaron began playing with the Braves’ minor league team in Wisconsin – the Eau Claire Bears. Then 18 years old, he arrived at the Eau Claire airport with a cardboard suitcase, admitting he was “scared as hell,” not knowing what to expect.

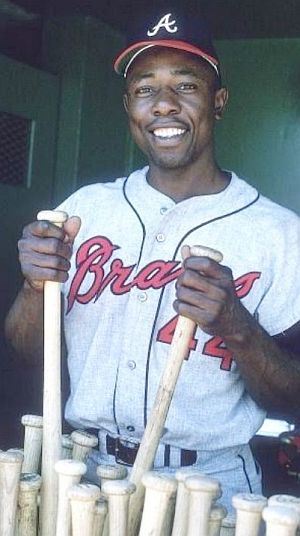

1953. Henry Aaron picking out a bat during his season with the Jacksonville Braves in Jacksonville, Florida.

Amazingly, to that point, the right-hand hitting Aaron had batted “cross-handed,” that is, with his left hand above his right on the bat’s handle. Braves coaches soon fixed that and Aaron’s talents rose to fuller form. In his season at Eau Claire, Aaron hit .336, had 116 hits, nine home runs and scored 89 runs. That performance earned him the Northern League Rookie-of-the-Year award.

In 1953, Aaron moved up in the minor league ranks, sent south to Florida to play for the Class A Jacksonville Braves of the South Atlantic League. Aaron and two other Jacksonville players that year were the first blacks to play in the Deep South “Sally League,” as it was called. It was still the Jim Crow era there, and Aaron had to live with a black family in town. On the road, he and other black players had to stay in black hotels and would not be served at roadside restaurants, remaining on the bus while some white teammates brought food out for them.

During games, home and away, there was a steady stream of racist taunts from spectators and opposing players, some calling the black players “alligator bait” and worse, others throwing stones. At least one white Jacksonville player, according to Aaron, Massachusetts player Joe Andrews, would come to the defense of the black players and try to diffuse problems with fans.

On the field, meanwhile, Hank Aaron continued to excel. He led the league in batting average (.362), runs (115), hits (208), doubles (36), RBIs (125) and total bases (338), leading the Jacksonville Braves to the 1953 South Atlantic League championship and winning the league’s Most Valuable Player award.

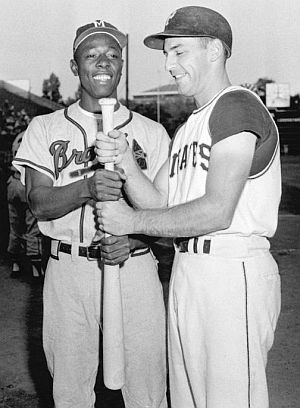

1953 Wire Photo. Hank Aaron of the Jacksonville Braves, shown with Jacksonville manager, Ben Geraghty.

During his time at Jacksonville, Aaron had high regard for his manager, Ben Geraghty, who he called “the greatest manager I ever played for,” citing Geraghty’s ability to get the most out of his ballplayers, “treating every player as an individual.” Aaron would later say, “…Ben never told me how good I was—just how good I could be. He taught me to study the game and never to make the same mistake twice.” And during road trips, Geraghty would complain to restaurant management who would not serve his black players, would visit with them at their black-only hotels, and ate meals with them in restaurants where they were served. As for Aaron’s baseball ability, Geraghty later told Sports Illustrated that Aaron was “the most natural hitter I ever saw.”

After Jacksonville, there was some time playing winter ball in Puerto Rico, preparing the young prospect for the Big Leagues. Yet, it wasn’t entirely clear that Henry Aaron would make the big jump and might have to spend more time in the minors. Still, by spring training time, it was off to the Milwaukee Braves.

In early 1954, as spring training began, the Braves’ left fielder, Bobby Thomson, broke his ankle. Aaron, then fresh from his stellar year in Jacksonville, was named Thomson’s replacement and began playing in the outfield.

It was about then that Aaron was renamed “Hank” by a local sports reporter to make him seem more approachable (though Aaron preferred Henry and regarded Hank his baseball name).

With the Milwaukee Braves, Aaron joined a lineup that included some good hitters, among them: third baseman, Eddie Mathews; catcher Del Crandall, and first baseman. Joe Adcock. Standout Braves pitchers then included Warren Spahn, Lew Burdette, and Bob Buhl.

Hank Aaron would hit his first home run for the Braves in April 1954, his seventh game. In his first year with the Braves he hit .280 with 13 homers and 69 RBIs and finished fourth in the NL Rookie-of-the-Year voting.

The next year, 1955, he led the National League in doubles with 37, hit 27 home runs, had 106 RBIs, and was named to his first All-Star Game.

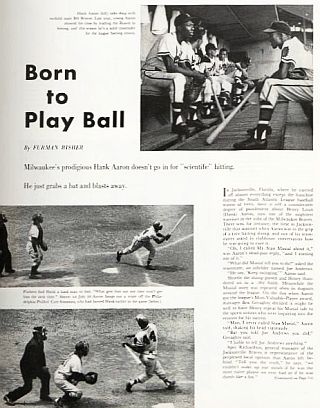

By this time, he was getting some national press. In late August 1956, The Saturday Evening Post, a popular weekly magazine of that era, did a feature story on Aaron titled, “Born to Play Ball.”

August 1956. First of a 3-page piece on Hank Aaron by The Saturday Evening Post, “Born to Play Ball”.

Two photos running at the bottom of the first page, as shown at left, have him striking out against pitcher Curt Simmons of the Philadelphia Phillies and then hitting a triple off Simmons the next time at bat. The caption notes “he’s hard to fool, and what pitches get him out one time, won’t get him out the next time”.

The story also noted: “…Over the last two and a half seasons in Milwaukee, he has carved out a reputation as probably the best fast-ball hitter in the league, and a man who should be up there among the batting leaders for many years to come.”

Indeed. By season’s end 1956, Aaron had hit .328, won the National League batting championship, and became the only player in baseball with 200 hits. Then came 1957.

Aaron was just 23 years old, in his fourth big-league season, and about to have one of his best years ever. A Sports Illustrated story reporting on Aaron offered this account of his early performance that year:

“…This year, Aaron has been hitting everything within reach. He beat the Redlegs 1-0 with a home run on April 18. On May 2 at Pittsburgh he had five singles; the next day he drove in four runs with a double, a triple and home run. On May 5 against the Dodgers he hit two singles, a double and a home run. On May 18 he beat Pittsburgh 6-5 by driving in four runs with two homers and a single. He drove in both runs in a 2-1 victory over the Dodgers June 27. On June 29 he began a streak in which he hit seven home runs in eight games. And on July 16-17 he had six for seven…”

But that was just the warm up. In the home stretch that year, the Milwaukee Braves were in a race with the St. Louis Cardinals for the National League pennant. The Braves needed just one more victory to take the National League flag. On September 23, 1957, the Cardinals came to Milwaukee’s County Stadium to play the Braves in a late season game that went into extra innings. By the 11th inning the score was tied, 2-2. Billy Muffett was then pitching for the Cardinals, and he hadn’t given up a home run all season. But then Henry Aaron came to the plate, and soon found a pitch he liked. He connected on a Muffett curve ball that took off toward center field, where Wally Moon raced back toward the fence with the 402-foot sign. Moon jumped in vain but couldn’t snag the ball as it sailed over the fence and onto the ground in front of some cedar trees beyond. That was Aaron’s 43rd homer that year, and none bigger, as it became the only walk-off home run to win a pennant for a major league team. Aaron was greeted by jubilant teammates who carried him off the field, pictured in some of the front-page newspaper coverage the next day, as shown below in The Janesville Gazette.

September 24, 1957. Janesville, WI newspaper headline proclaims Milwaukee Braves clinching the National League pennant, including a photo of Henry Aaron (last of 4) being carried off the field by teammates. Other headlines on that same front page report on the Little Rock, Arkansas school integration strife.

But The Janesville Gazette paper also bore another headline of the times just below the pennant-winning news. That headline read: “Ike Orders Arkansas Guard Federalized To Handle School Crisis,” a story about racial strife where violence loomed over the court-ordered integration of Central High School in Little Rock. Another photo (not shown) – an AP wire photo on the lower half of that same front page – showed a black reporter from the Tri-State Defender newspaper of Memphis, TN being kicked by a white protestor as the reporter tried to cover the Little Rock story. And although baseball was moving along in its own sphere, seemingly apart from the realities of Little Rock’s violence and American racism, the nation then was in the midst of its civil rights struggle; a struggle that Henry Aaron knew well, having experienced racism in his own life, including within baseball, which he would confront throughout his career.

But on the baseball field in 1957, Henry Aaron was giving a clinic on how to be a great hitter. In fact, he just missed winning a Triple Crown batting title that year, as he led the league in home runs (44) and RBIs (132), but finished third in batting average (.322), tied with Frank Robinson of Cincinnati at .322 and ahead of Pittsburgh’s Dick Groat at .315. Stan Musial took the batting title that year at .344. Aaron also led the league in total bases that year at 340 and was named the National League’s Most Valuable Player. Other Braves also had good years, led by the team’s pitchers: Warren Spahn went 21-11 with a 2.69 ERA and won the Cy Young Award; Lew Burdette went 17-9 and beat the New York Yankees three times in the World Series. Bob Buhl went 18-7 with a 2.74 ERA. Third baseman Eddie Mathews had 32 homers and 94 RBIs.

Mickey Mantle of the New York Yankees and Henry Aaron of the Milwaukee Braves, respective power hitters for their teams, squared off in the World Series of 1957 and 1958. Mantle had a sub .300 showing in both series (.263 and .250 respectively), while Aaron tore up Yankee pitching in 1957, hitting .393 and held his own in 1958 at .333.

In the 1957 World Series that year the Braves faced the New York Yankees and their famous slugger, Mickey Mantle. Then in his prime, Mantle had won the American League batting title with a .365 average, hitting 34 home runs and 94 RBI’s. Mantle, like Aaron, was also his league’s MVP that year. Yet Henry Aaron had the better World Series, helping the Braves prevail in seven games to take the crown. Aaron had a stand-out series, hitting .393 with three homers and seven RBIs.

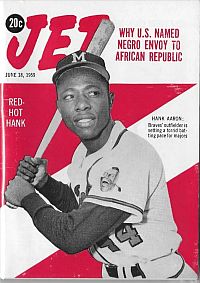

Jet magazine, June 1959.

In 1959, Aaron posted a career best batting average of .355. And in one game that year, on June 21, 1959, against the San Francisco Giants, Aaron hit three two-run home runs, the only time in his career he would accomplish the rare three-homers-in-one-game feat.

In the black press that year, Jet magazine featured Aaron on the cover of its June 18 issue with the tag line, “Red Hot Hank” – Hank Aaron, Braves’ Outfielder is Setting A Torrid Batting Pace for Majors”.

After the 1959 season there was a short-lived television production called Home Run Derby, and Henry Aaron won more of the competitions and the most prize money, $13,500, than any of the 18 other participants, which included Willie Mays, Mickey Mantle, Duke Snider, and others. With his prize money, Aaron acquired a grocery store for his father and two houses in Mobile.

UPI story, early 1960, about Henry Aaron endorsing JFK for President.

Yet according to sports journalist and Aaron biographer, Howard Bryant, Aaron and other black athletes endorsing Kennedy at that time were sought out, in part, to help off-set Jackie Robinson’s endorsement of Kennedy’s rival in the Wisconsin primary, Senator Hubert Humphrey.

(After Humphrey lost the nomination to JFK, Robinson switched his support to Republican candidate for President that year, then Vice President Richard Nixon).

In any case, Kennedy later wrote to Aaron in June 1960 thanking him for his help, adding that he hoped Aaron, then in a bit of slump, would rise above the .300 mark again.

On July 3, 1960, Aaron hit his 200th career home run in a game against the Cardinals. He ended 1960 with a .292 average, hitting 39 home runs and 126 RBIs.

In 1961, Aaron continued his workmanlike performance – playing 155 games with 603 at bats, 197 hits, 115 runs scored, 34 home runs, 120 RBIs, and a .327 batting average.

In 1962, among Aaron’s press coverage, was an appearance on the cover of Sport magazine in June, featuring a photo of Aaron with bat on his shoulder and story tagline that read: “Hank Aaron’s Hitting Secrets.”

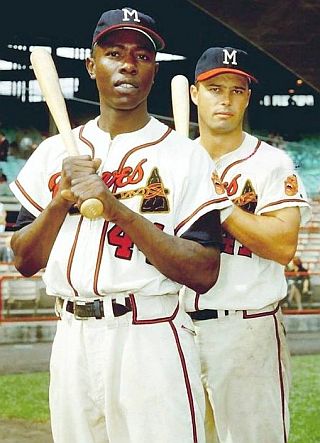

Hank Aaron & Eddie Mathews hold the all-time record for home runs by two teammates, at 863, hit between 1954-1966.

In fact, but for a few points in batting average, Aaron, for a second time, nearly captured the 1963 Triple Crown batting title, leading the league with 44 homers and 130 RBIs, but losing out on average to Tommy Davis of the Los Angeles Dodgers — .326 to Aaron’s .319.

Early that year, on April 19, 1963, Aaron had notched his 300th career home run against the New York Mets. He also had 201 hits that year – second best in the league – led the league in runs scored and was second in stolen bases. In fact, he was the third player in major league history at that point to make the “30-30 club” – hitting 30 or more home runs with 30 or more stolen bases. And he continued to be a nightmare to some of the league’s best pitchers, such as Don Drysdale and Juan Marichal.

In 1964, Aaron slowed off his 1963 pace on home runs and RBIs – with 24 and 95 respectively for the year – and a .328 batting average. Earlier that year, on April 20th against the Philadelphia Phillies, he hit his 400th career home run.

Meanwhile, in another home run category, by late August 1965, Aaron and his Milwaukee Braves teammate, Eddie Mathews, became the top home-run hitting duo in baseball history, passing the famous New York Yankee pair of Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig, who hit 859 home runs between them from 1923-1934. Aaron and Mathews would together hit 863 home runs during the 1954-1966 period, establishing a new major league record for teammates.

Henry Aaron, meanwhile, was also becoming more attentive to and involved with racial and civil rights issues. In 1961, Aaron and other black teammates spoke out about the Milwaukee Braves segregation policies and practices occurring during spring training in Florida. Since first joining the Braves in 1954, and attending spring training in Bradenton, Florida through the 1950s, Aaron and other Braves’ black players had to stay in a separate rooming house in the black section of Bradenton rather than with the rest of the team who stayed at the well-appointed Dixie Grande Hotel on the Manatee River, where white players were put up in style and comfort. Other MLB teams with spring training in Florida also had similar policies. But these spring training segregation practices were challenged in 1961 by Aaron and others — including the NAACP and a few journalists — and were mostly ended by the Braves and other MLB teams in 1961.

1964. Jackie Robinson book in which Henry Aaron wrote one chapter. A later edition includes Spike Lee introduction. Click for copy.

In the Robinson book, Aaron described being knocked down by white pitchers throwing at him simply because he was black – noting that Eddie Matthews, who batted ahead of him and as good a hitter, wasn’t knocked down. Aaron also noted in the Robinson book that he had read James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time, an important book on the black perspective, first published in 1963. Aaron biographer, Howard Bryant, explained that Aaron had come across Baldwin on a TV talk show once when he was surfing late night TV offerings, and hearing him talk, sought out his book.

Henry Aaron wasn’t only about baseball by the mid-1960s, but was also thinking about how to live his life too good effect off the field. “…He had actively begun to reinvent himself..,” according to biographer Howard Bryant, “… all the while growing more resolute in his belief that his baseball talent meant nothing if it did not translate to improving the general condition of the world around him.” It was about this time as well, that the Milwaukee Braves began their prospecting to move to another city.

Heading South

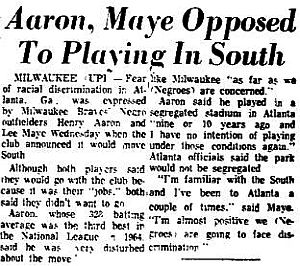

Part of a 1964 wire service story on views of Henry Aaron and Lee Maye on moving to Atlanta with Braves.

“I have lived in the South, and I don’t want to live there again…,” said Aaron at one point. “…We [ meaning he and family] can go anywhere in Milwaukee. I don’t know what would happen in Atlanta.”

Aaron, in fact, had been airing his concerns about a move to Atlanta since the plans were first announced, and it appeared from some of his statements that he was not willing to go.

“I just won’t step out on the field” if the Braves moved there, he told a wire service reporter. “I certainly don’t like the idea of playing in Atlanta and have no intention of taking my family there.” He worried about his children, should they have to attend segregated schools.

Yet Atlanta was pushing hard for the Braves. The city then had no big league sports teams at all. In fact, as of 1964, when the idea first emerged, there was no major league ball club anywhere in the Deep South. But Atlanta was offering all kinds of incentives – a new stadium, TV deals, some revenue perks, Coca-Cola patronage, etc.,. Yet the 1960s were also a tense time for civil rights. 1964, in fact, was the year three civil rights workers were murdered in Mississippi. Atlanta had made slow progress in civil rights, with public places then “voluntarily” opened to blacks, the result of pickets, legal action, and activist pressure. But the city still had “a long way to go” on schools, housing and jobs for blacks.

Black leaders in Atlanta, however, were pinning their hopes, in part, on Henry Aaron. As Whitney Young wrote in one of his newspaper columns at the time, Aaron not joining the Braves in Atlanta would “dash the hopes of Atlanta’s Negro Leaders who have worked tirelessly to bring professional baseball and football clubs to Georgia’s first city.Whitney Young wrote of Atlanta’s black leaders: “It is their hope that Aaron’s big bat and superstar popularity will help knock Jim Crow out of town.” They’ve labored in the conviction that integrated pro teams would dramatically demonstrate what citizens of color can accomplish given equal opportunities. It is their hope that Aaron’s big bat and superstar popularity will help knock Jim Crow out of town.” Some wrote directly to Aaron encouraging him to come to Atlanta.

C. Miles Smith, then president of Atlanta’s NAACP, wrote that Atlanta was a progressive, bustling city where conditions for blacks were steadily improving. Atlanta-based lawyer and Morehouse College graduate, Walter J. Leonard, asked Aaron in an October 1964 letter, “to give Atlanta a chance.,” adding, “You will find Atlanta to be a city with its eyes fixed on the future.” Georgia State Senator and African American Leroy Johnson wrote Aaron, acknowledging: “Having been born and raised in the South, I can understand your fears and apprehensions relative to your moving to the south with the Braves Baseball Team.” But Senator Johnson asked him to reconsider his perception of Atlanta, noting the city had made much progress in the last five years.

In the end, Aaron did go to Atlanta with the Braves in 1966, and he became “the first black superstar in the South,” according to Bob Hope, a former Braves promoter. Howard Bryant, later writing of Aaron in The Last Hero, noted: “Henry had never considered himself as important a historical figure as Jackie Robinson, and yet, by twice integrating the South — first in the Sally League [with Jacksonville ] and later as the first Black star on the first major league team in the South (during the apex of the civil rights movement, no less) — his road in many ways was no less lonely, and in other ways far more difficult.”

Sports Illustrated photo and caption from August 1966 story: “Rarely fooled by a pitch, Aaron moves his weight forward but keeps his bat back, cocked and ready to commit.”

In the baseball press, meanwhile, Aaron’s hitting talents were feted in an August 1966 Sports Illustrated story by Jack Mann, titled, “Danger With a Double A.”

The story focused on how Aaron, after 13 years in the majors and now in Atlanta, was still torturing National League pitching, acquiring the respectful nickname, “Bad Henry” for his hitting prowess.

As Aaron himself would explain on what he had learned: “I don’t go up there swinging at what they throw me anymore. I’ve studied and concentrated, and now I wait until I get my pitch.”

Los Angeles Dodger’s pitching ace, Sandy Koufax, agreed, telling Sports Illustrated at the time: “He sure as hell does… Did you see him go after that curve I hung for him today? That was a mistake, and you don’t get away with a mistake to Bad Henry. He’s the last guy I want to see coming up there…Some guys give me more trouble one year than another. But Aaron is always the same. He’s just Bad Henry.”

In 1966 Aaron showed his new home-town fans in Atlanta exactly what he could do with a baseball bat: hitting 44 home runs and driving in 127 runs, leading the National League in both categories while finishing 8th in MVP voting. Again in 1967, he had league-leading totals in runs scored with 113 and home runs at 39, while adding 109 RBIs and batting at .307. He finished 5th in 1967’s MVP voting.

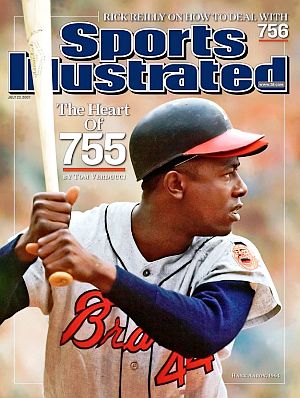

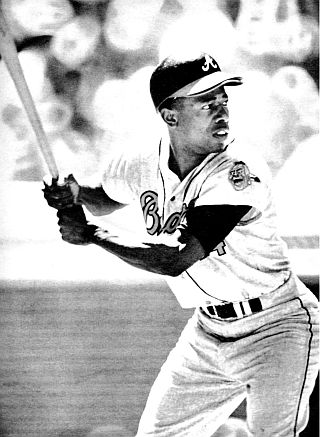

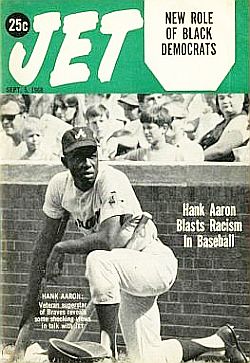

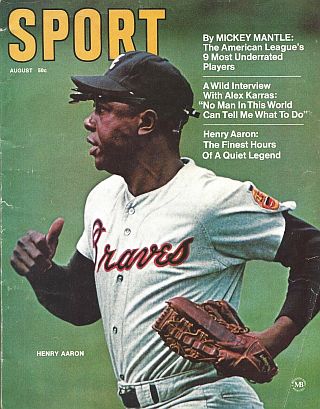

Still, as consistent as Aaron was year-to-year, posting great hitting numbers, he didn’t always get the same level of press attention that other great players of his day received. Acknowledging this, Sport magazine, on the cover of its July 1968 edition, included a photo of Henry Aaron in his betting stance at the plate, along with cover tagline: “Hank Aaron: What It’s Like To Be A Neglected Superstar.” But in that same month, in mid-July 1968, Aaron hit his 500th home run. Surely, after reaching that rare milestone, he would be “neglected” no more. His 500th homer came on July 14th against Mike McCormick of the San Francisco Giants during a Braves home game in Atlanta.

Portion of the New York Times sports page story of July 15, 1968 with Associated Press photo of Henry Aaron hitting his 500th career home run in Atlanta. His focus is seemingly that of long-standing hitter’s goal of “seeing the bat hit the ball”.

The July 15, 1968 edition of the New York Times ran an Associated Press photo of Aaron that captured him hitting his 500th home run at the Atlanta Braves home park, along with headline: “Aaron Clouts No. 500 as Braves Top Giants, 4-2.” The 400-foot blast soared over the fence in left-center field. It was Aaron’s 19th homer of the season. He was met at home plate by teammates and the president of the Braves, Bill Bartholomay, who presented him with a trophy.

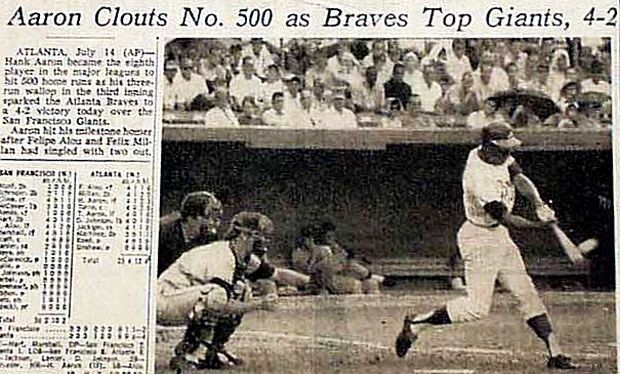

September 5, 1968. Jet magazine runs feature story, “Hank Aaron Blasts Racism in Baseball.”

The New York Times, in its July 15th story, reported that Aaron “still expects to have two or three good years, and most baseball experts predict that he will go over the 600-homer mark.” Indeed. “Bad Henry” still had lots of firepower remaining.

Hank Aaron was also speaking out more about the racism he experienced and continued to find in major league baseball. Jet magazine of September 1968, for example, included a feature story on Aaron titled, “Hank Aaron Blasts Racism in Baseball.” Among his concerns: the lack of black managers and near total absence of minorities in the front office, as well as salary discrepancies between black and white players. It wasn’t the first time he had addressed these topics.

Back in Milwaukee in October 1965 he wrote an article with Jerome Holtzman for Sport magazine, titled “I Could Do The Job,” in which he included himself, among other black players, who he believed could manage in major league baseball, then naming Jackie, Robinson, Bill White Billy Bruton, Junior Gilliam, Ernie Banks and Willie Mays as “could be” managers. Aaron would continue to raise these issues through his active and later years.

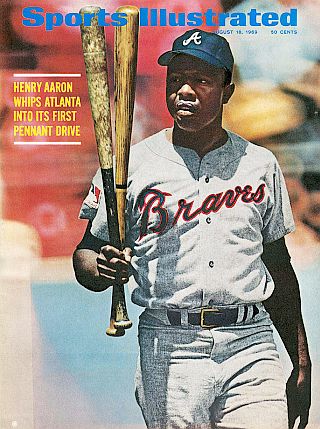

August 1969: “Henry Aaron Whips Atlanta Into Its First Pennant Drive,” Sports Illustrated. Click for custom poster.

1969

In the next baseball season, meanwhile, by July 31, 1969, Aaron hit his 537th home run, passing Mickey Mantle’s total of 536. Mantle had retired after the 1968 season. This put Aaron at No. 3 on the all-time career home run list. Only Willie Mays and Babe Ruth had more.

In August 1969, Sports Illustrated featured Aaron on the magazine cover with the story “Henry Aaron Whips Atlanta Into Its First Pennant Drive.” And yes, by season’s end, the Braves had won the National League West divisional title, as Aaron contributed 44 home runs, 97 RBIs, and a .300 batting average. He would later finish third in National League MVP voting.

It was then the first year of the divisional system in the post-season play-offs, and the Braves faced the New York Mets who had won the NL East title in a best-of-five National League Championship Series.

The “Miracle Mets” that year were on fire and swept Atlanta in three games. Aaron, however, did his part, hitting .357 in the series with three homers and seven RBIs. But there was more ahead for Aaron the following year.

1970

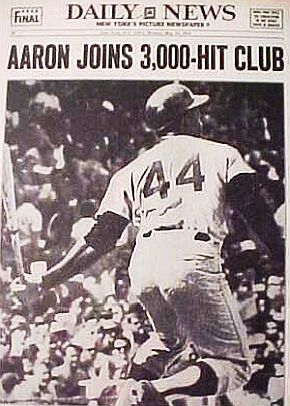

On May 17, 1970, Henry Aaron reached another hitting milestone: his 3,000th base hit. It came against the Cincinnati Reds at Crosley Field in Cincinnati. This was the Cincinnati club of Pete Rose and Johnny Bench, and at the time, they held first place with the Braves in second. But Aaron’s hit was the big news of the day despite the fact the Braves lost both games of a doubleheader. With his hit, Aaron became the ninth player in MLB history to join the exclusive 3,000 hit club of Hall of Famers and hitting legends.

Among the press coverage Aaron received for that achievement was a full-page photo in the New York Daily News of Aaron completing his swing on his 3,000th hit. Sports Illustrated also ran a cover story on Aaron’s 3,000th hit its May issue, featuring a photo of Aaron at center on the cover surrounded by smaller photos of the 8 other legends who had already done it: Cap Anson (1897), Honus Wagner and Nap Lajoie (both 1914), Ty Cobb (1921), Tris Speaker and Eddie Collins ( both 1925), Paul Warner (1942), and Stan Musial (1958). Musial, then retired, came to the game in Cincinnati to greet Aaron after he had singled up the middle for his 3,000 hit.

The 3,000 hit club is a rarefied place, where only the very best hitters land. A number of other famous and great ballplayers never made it to the 3,000 hit club, among them: Lou Gehrig, Babe Ruth, Ted Williams, Joe DiMaggio, Rogers Hornsby, Mel Ott, Mickey Mantle, and others. So Henry Aaron was now in quite a special place, and he treasured it more than his home run records, as he believed it distinguished him to be an all-around hitter and team player. Yet he was also the first player with 3,000 hits and 500 home runs. In fact, for his 3,001st hit, on that same day in Cincinnati, Henry Aaron hit a home run over the center field fence. That one was No. 570 for Henry Aaron.

In May 1970, at the time of his 3,000th hit, Aaron mused on the Babe Ruth home run record. He told Sports Illustrated: “This year and next are critical ones for me if I’m going to catch Ruth. I would almost have to have a 50 [home run] year in one of the two seasons…” But he also seemed pleased with joining the 3,000 hit club. “Sure, catching Ruth would be a thrill, but achieving 3,000 hits is more important because it shows consistency…” And indeed, for the last 16 years, since 1954, Henry Aaron had been a dependably consistent and dependably good hitter. And more was yet to come.

Another side of Henry Aaron shows how he could be a gentleman and sportsman on the field when circumstances warranted. In a May 1970 game with the Chicago Cubs when Aaron was on a hot streak, hitting the ball especially hard, he hit a scorching line-drive shot that caught Chicago Cubs rookie pitcher Joe Decker on the forearm hard and landed him behind the mound. Sports Illustrated writer William Leggett described the scene: “…When Aaron reached first safely he looked at Decker, waited for time to be called and then walked over to the pitcher’s mound. ‘I thought I had broken his wrist,’ Aaron said. ‘I want my hits but I don’t want to hurt anyone. I was kind of afraid for the kid. It could have all been gone for him right there. But he was O.K. I told him I was sorry’.”

August 1970, Hank Aaron on the cover of Sport magazine; “Henry Aaron: The Finest Hours of Quiet Legend.”.

At the game, Tobach noted the home-made signs in the crowd that night: “We Love Henry,” “715 Comes Next,” and “Hammerin` Hank is Our Hero.” He also noted that Aaron’s latest round of accomplishments placed him near or at the top of all-time baseball stars — “a living, playing legend”.

Tobach would write a “Sport Special” on Aaron titled, “The Finest Hours of a Quiet Legend,” praising Aaron’s career, though noting that his talents were often taken for granted. But Henry Aaron wasn’t the aggressive type; he didn’t go around touting his own talents; it just wasn’t his style.

But writing in that same Sport issue in another story, Mickey Mantle, then retired, offered the following about Aaron:

“…What was lucky for me, as far as publicity was concerned, was playing in New York, with all its big TV and radio networks, the newspaper wire services and all the magazines. Willie Mays and I, we broker in together in 1951 and we got so much publicity because we played in New York. Hank Aaron didn’t get all that publicity because he didn’t play in New York, and Hank Aaron, in my mind is the most underrated ballplayer of my era. If he had played in New York, he would be as big today as Mickey Mantle or Willie Mays or anybody.”

Mantle had also praised Aaron earlier in a June 1970 Baseball Digest story: “As far as I’m concerned, Aaron is the best ball player of my era. He is to baseball of the last 15 years what Joe DiMaggio was before him. He’s never received the credit he’s due.” Meanwhile, Henry Aaron finished the 1970 season with a .298 batting average, 38 home runs, and 118 RBIs.

1971-72

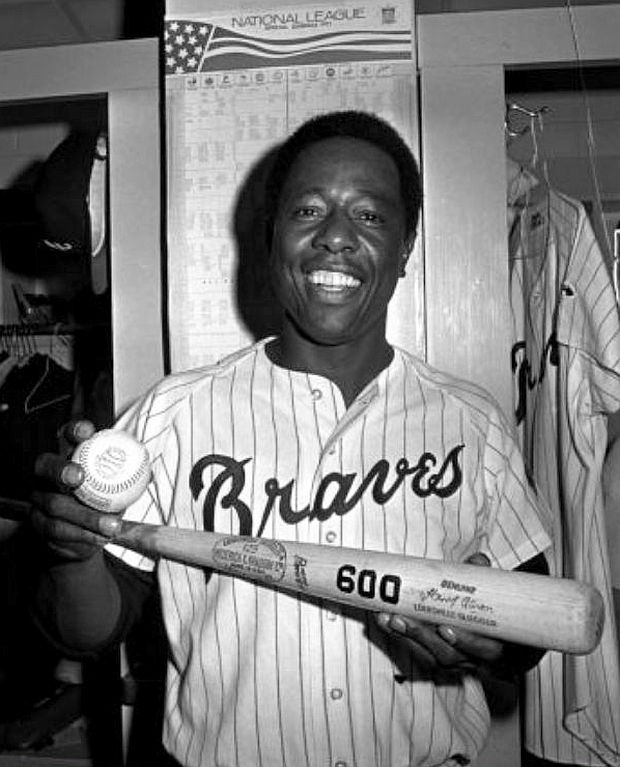

Early in the next season, on April 27, 1971, Henry Aaron hit his 600th career homer off San Francisco’s Gaylord Perry, then joining Willie Mays and Babe Ruth as the only players to reach that milestone.

April 1971. A pleased Hank Aaron holds bat & ball for his 600th major league home run – a high fly of 350 feet that landed on the stadium wall behind the left field fence at Atlanta’s stadium. AP photo / JS.

In addition to his 600th home run, Aaron had a monster 1971 season at the plate as well with 162 hits, a career high 47 home runs, 118 RBIs, and a .327 batting average. Aaron’s slugging percentage that year was a career high .669 and led the National League. He also finished third in the National League MVP voting.

April 13, 1972. Jet magazine story - "Aaron Aims His Bat to Break Ruth's Record".

Toward the end of the 1972 season, Aaron also broke Stan Musial’s record for total bases, at 6,134. This was another record of importance to Aaron, reflecting overall performance and not just home run power.

Still, as the 1972 season closed, Aaron stood at 673 career home runs. He was now 41 home runs away from tying Babe Ruth’s record. But that proximity also had a dark side.

“In 1972, when people finally realized I was climbing up Ruth’s back, the ‘Dear N——r’ letters started showing up with alarming regularity,” Aaron would later write in his 1991 memoir. “They told me no n——-r had any right to go where I was going.” And it would get worse in 1973 and 1974. More on this to come.

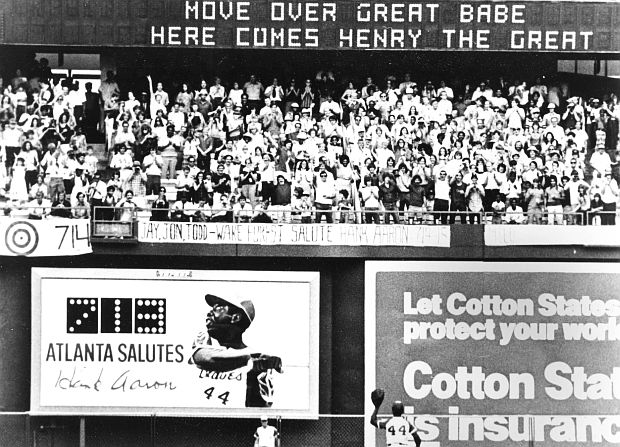

1973

In the 1973 baseball season, the Atlanta Braves front office was hyping their home run star with a special press booklet on Aaron and his bid to upend the Babe Ruth record: “The greatest sports story in history is taking place in Atlanta,” it began, adding that “no single record is quite so precious as Babe Ruth’s career home run total of 714.” But this “greatest record of all records” is now in the sights of Hank Aaron. “Each Aaron homer becomes an incredible event to remember . . . and a long line of the game’s most sacred batting marks are falling one at a time to Hank’s mighty bat.” The sports press, too, was abuzz with Henry Aaron’s home run possibilities.

Henry Aaron, for his part, then making $200,000 a year, was otherwise living a modest life in Atlanta. Then a recent divorcee of two years, he had a two-bedroom apartment and he drove a Chevy Caprice. Two of his teenage sons lived with him that summer of 1973. Henry was also engaged to Billye Williams, a 36-year-old widow who taught English literature at Atlanta University and was also director of community relations at Morehouse University. Henry and Billye had met a few months after his divorce, when she was assigned to interview several members of the Braves.

Meanwhile, on the baseball field, Henry Aaron was no longer a young guy in baseball terms, now 39 years old. He had already slowed down a bit, playing fewer games in the preceding seasons. Yet Henry Aaron went about his craft just as he had done in the past, steadily, day by day.

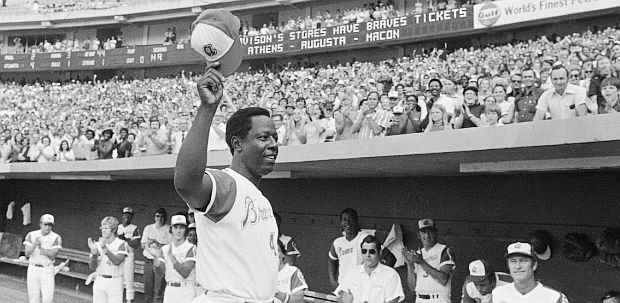

July 21st, 1973, Atlanta stadium. Henry “Hank” Aaron tips his hat to the crowd then lauding his latest baseball milestone of hitting his 700th career home run during game with the Philadelphia Phillies.

By the end of April 1973, he was hitting a mere .125 and had logged 5 additional home runs. In May the average went up to .321 and he added 8 more home runs. By June he was hitting .303 with 7 more home runs. July was much the same: 8 home runs and batting .324. But on July 21st, during a home game in Atlanta against the Philadelphia Phillies, he hit his 700th career home run.

After he hit No. 700, the hate mail and racial insults ramped up, and more attention was paid to his and his family’s protection and safety. But still managing to take the field in August 1973, Aaron raised his average to .382 that month adding 5 more home runs, then finishing the year in September, when he hit a sizzling .426 that month with 7 more home runs.

September 1973. Associated Press photo of Henry Aaron completing a swing on a likely hit, as he had a very hot August and September, hitting 40 home runs for the year and finishing just one shy of Ruth's record career total .

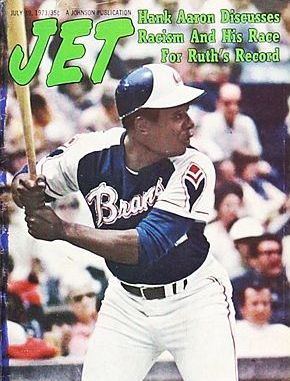

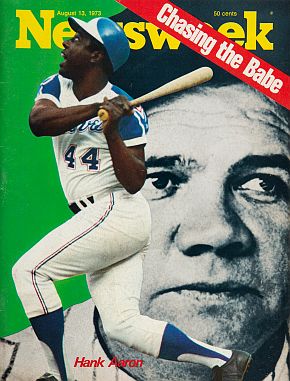

Through the summer of 1973, there had been a range of coverage in the press and media about Aaron approaching the Ruth record, a few that mentioned the race issue. In July 1973, Jet magazine ran a cover story with tagline, “Hank Aaron Discuses Racism and His Race for Ruth’s Record.” The August 13, 1973 edition of Newsweek featured a more general cover story on Aaron’s pursuit of the home run record, showing him in his Braves uniform completing a batting swing, superimposed over a larger photo of Babe Ruth in the background, with the cover tag line, “Chasing The Babe.”

July 19th, 1973 edition of Jet magazine with cover photo and tagline: “Hank Aaron Discuses Racism and His Race for Ruth’s Record”. |

August 13th, 1973 edition of Newsweek with Henry Aaron on the cover completing a swing superimposed over a large Babe Ruth photo in background with tagline: “Chasing The Babe”. |

Although he had a very good 1973 season, hitting 40 home runs at age 39, Aaron finished the 1973 season, after 392 at-bats, at 713 career home runs, one shy of tying Ruth’s record.

In his last at bat for the 1973 season in Atlanta, Aaron had popped out to second base, and then he took his defensive position in the 9th inning out in left field. That’s when he was totally surprised by what happened next, as he would later write in his 1991 autobiography, I Had a Hammer:

…When I got out to left field for the ninth inning, the fans out there stood up and applauded. Then the fans on the third base side stood up an applauded, and fans behind right field and home plate. There were almost 40,000 people at the game – the largest crowd of the season – and they stood up and cheered me for a full five minutes. There have been a lot of standing ovations for a lot of baseball players, but this was one for the ages as far as I was concerned. I couldn’t believe that I was Hank Aaron and this was Atlanta, Georgia. I thought I’d never see the day. And God almighty, all I’d done was pop up to second base…. I took off my cap and help it up in the air, and then I turned in a circle and looked at all those people standing and clapping…. and to tell you the truth, I didn’t know how to feel, I don’t think I’d ever felt so good in my life. But I wasn’t ready for it.

Photo of Henry Aaron – No. 44, small figure, bottom center, at his position in the outfield during game – waving to, and acknowledging fans’ ovation for him at Atlanta Braves stadium on the last game of the season, even though he had 713, but unable to tie or surpass the Babe Ruth record during his at bats in that last game of 1973.

Still, the one real fear that Henry Aaron had as he closed out the 1973 baseball season – given the vicious threats he had received that year (see “Henry’s Hate Mail” below) – was that he might not live to see the 1974 season. Despite the last-game ovation and positive fan reaction for Aaron at the end of the 1973 season, the year had been a hellish one for he and his family. And the long wait until his next at bat in the 1974 season was now six months away — time enough for the bigots and haters to continue their hurtful craft, which they did.

___________________________________________

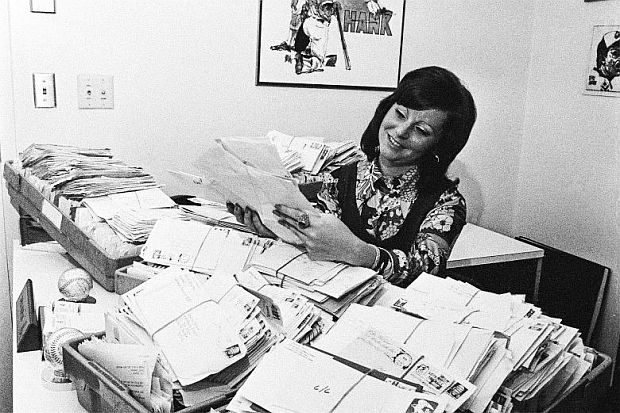

Henry’s Hate Mail

1972-1974

Beginning in 1972, Aaron had hired a secretary named Carla Koplin to deal with his mail – both his outgoing mail to fans requesting autographs, baseball cards, or photos, and other incoming mail, including the hate mail that increased in volume between 1972 and 1974. In 1973 alone, according to the U.S. Post Office, Henry Aaron would receive some 930,000 pieces of mail. Koplin organized the mail into good and bad stacks – and a separate pile of hate mail, with threatening letters reported to the FBI. The hate mail was saved for Aaron, who kept and stored the letters in his attic.

In 1972, Henry Aaron had hired a secretary named Carla Koplin to deal with his mail – both his outgoing mail to fans requesting autographs, baseball cards, or photos, and other incoming mail, including the hate mail that increased in volume between 1972 and 1974.

The letters came with scrawled KKK hoods, some that read, “You black animal,” and “You will die in one of those games,” and much worse. In the 1994 companion book to the Ken Burns PBS-TV series on the history of baseball, titled Baseball: An Illustrated History (based on the documentary film transcript), there is a sampling of excerpts from some of the racist mail Aaron received, as follows:

Dear Nigger: You black animal. I hope you never live long enough to hit more home runs that the great Babe Ruth.

Dear Hank Aaron: I hope you get it between the eyes.

Dear Brother Hanks Aaron: I hope you join Brother Dr. Martin Luther King in that Heaven he spoke of….

Dear Nigger Henry: It has come to my attention that you are going to break Babe Ruth’s record… I will be going to the rest of your games and if you hit one more home run it will be your last. My gun will be watching your every black move…

Another writer also threatened to shoot Aaron, as indicated in the letter shown below, written in 1973, with that writer listing the game dates and locations in 1973 he said he would be monitoring, accompanied by a shooting sketch at the bottom:

Sample of hate mail letter written to Henry Aaron threatening his life during the 1973 season.

It was threats of this sort that had prompted FBI monitoring and a body guard for Aaron. Some threats also came to those providing positive press coverage of Aaron. Lewis Grizzard, then executive sports editor of the Atlanta Journal, reported receiving numerous phone calls citing the journalists as “nigger lovers” for covering Aaron’s home run chase. Carla Koplin, Aaron’s secretary, also received some threats. “They knew I was white, Jewish, and working for a Black man,” she later explained.

After Aaron had talked publicly about his hate mail in the spring of 1973, that helped to generate a massive, national letter-writing campaign supporting him. The mail then turned in his favor, Koplin recalled, including that from school kids and others writing to support him. Koplin, meanwhile, would remain Aaron’s secretary through his later years and the two remained friends.

Henry Aaron, in his Atlanta Braves uniform, taking batting practice in the 1970s.

How Henry Aaron was able to take to the field, day after day during the Ruth chase, while receiving threats and daily hate mail, is truly amazing. He would later claim an ability to compartmentalize.

“I’ve always felt like once I put the uniform on and once I got out onto the playing field, I could separate the two – from say, an evil letter I got the day before or even 20 minutes before,” he would tell CNN in one interview. “God gave me the separation, gave me the ability to separate the two of them.”

And Henry Aaron was also on a mission, driven by a larger purpose.

“I had to break the record,” he would later write of pursuing Ruth’s home run mark. “I had to do it for Jackie (Robinson), and my people and myself and for everybody who ever called me a nigger.”

___________________________________________

1974

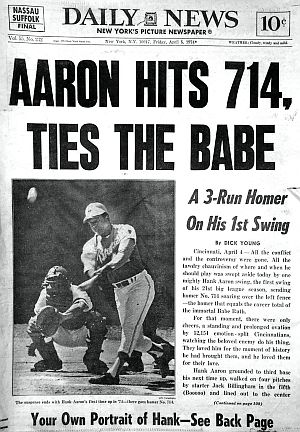

April 5, 1974. NY Daily News headline: “Aaron Hits 714, Ties The Babe.”

So, on April 4, 1974, in his very first at bat, before a sellout crowd of 52,154 at Riverfront Stadium — and on his very first swing of the season — Henry Aaron smacked a home run tying Babe Ruth’s record with No. 714. New York Times sports columnist Dave Anderson would write in his lead sentence for the next day’s story:

With the unobtrusive grace that has symbolized his career, Henry Aaron tied Babe Ruth’s record today with his 714th home run-a 400-foot, three-run line drive over the fence in left-center field at Riverfront Stadium on his first swing of the major league baseball season.

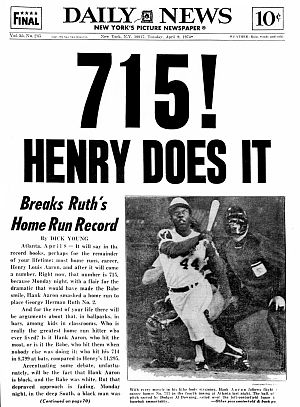

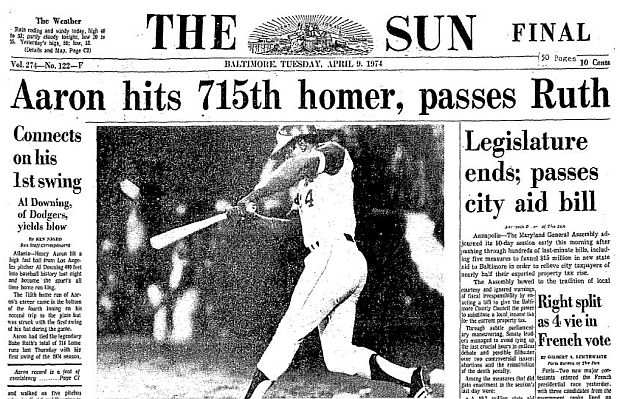

The Braves returned to Atlanta, and on April 8th, 1974 a crowd of 53,775 – then a Braves attendance record – turned out for what many believed would be baseball history. The game was also broadcast nationally on NBC-TV.

In Cincinnati, play was halted briefly following Aaron’s historic home run tying Babe Ruth, and a brief ceremony was held. Then U.S. Vice President Gerald Ford (R-MI) wished Aaron good luck for No. 715 “and a good many more,” while Baseball Commissioner Bowie Kuhn presented him with a trophy, calling him “a great player and a great gentleman.” Braves owner, Bill Bartholomay, presented a plaque to Aaron commemorating the home run, promising more celebration to come a few days later in Atlanta.

April 4th, 1974, Crosley Field, Cincinnati. After Henry Aaron of the Atlanta Braves hit career home run No. 714, tying the Babe Ruth record on opening day in Cincinnati, a short ceremony was held, with remarks from then U.S. Vice President Gerald Ford (w/ microphone), baseball commissioner Bowie Kuhn, and, not shown, Braves owner, Bill Bartholomay

The Braves returned to Atlanta, and on April 8th, 1974 where a crowd of 53,775 greeted them – then a Braves attendance record. Many attending the game that evening no doubt believed they would see baseball history. The game was also broadcast nationally on NBC-TV.

NY Daily News, April 9th, 1974: “715! Henry Does It!,” with photo of Aaron completing his swing, his eyes on the ball’s flight. Click for replica tin poster.

On a 1-0 count, Downing threw a pitch that came across part of the plate but within Aaron’s wheelhouse, and he unloaded on it. With his wrist-powered, whip-action swing, he drove the ball into deep left field, beyond the reach of Dodgers’ fielder Bill Buckner, and over the fence. That was it; Henry Aaron had done it! Baseball had a new Home Run King!

The stadium went wild as fans rose to their feet applauding Aaron’s feat for the ages. Cannons fired and fireworks exploded as Aaron circled the bases.

Vin Scully, the Dodgers’ famous play-by-play announcer, declared the resulting scene as a “marvelous moment for baseball … the country and the world … A black man getting a standing ovation in the Deep South for breaking a record of an all-time baseball idol.”

Yet, recalling the threats in Aaron’s hate mail, his body guard and protector, Atlanta detective Calvin Wardlaw, then not far away in nearby stands, watched anxiously as Aaron made his way around the bases. Wardlaw became especially concerned – his hand on a hidden revolver – as two young men who had run on the field came at Aaron between second and third base. They were happy fans, it turned out, coming to congratulate him. By the time Aaron arrived at home plate he was mobbed by teammates and family – first by his father Herbert, and then his mother, Estella, who managed her way through the throng of players to embrace her son.

Henry Aaron, arriving at home plate to a jubilant throng of his teammates after hitting record setting home run.

Aaron, for his part, who had been in the worst kind of a pressure cooker for more than two years, was just happy it was over with, and said so when first asked how he felt. Aaron’s record-setting baseball accomplishment, meanwhile, was front-page news all across America and beyond. Some front-page stories on Aaron’s feat in major newspapers — such as that shown below with the Baltimore Sun‘s front page — featured him in mid-swing hitting the ball for its historic departure. The New York Times of April 9, 1974, also ran a front-page headline with a photo of Aaron being embraced by his mother, sharing that space with other news of the day, including President Richard Nixon’s political woes, then the era of the Watergate scandal. Other headlines on Aaron’s home run touched on his humility and integrity. The Huntsville Times of Huntsville, Alabama, on April 9, 1974 offered: “Humble Hank Minimizes Historic 715th Homer.” The Atlanta Inquirer of April 13, 1974, noted: “Aaron Feat Thrills Nation. All Ages Hail Super Gentleman.”

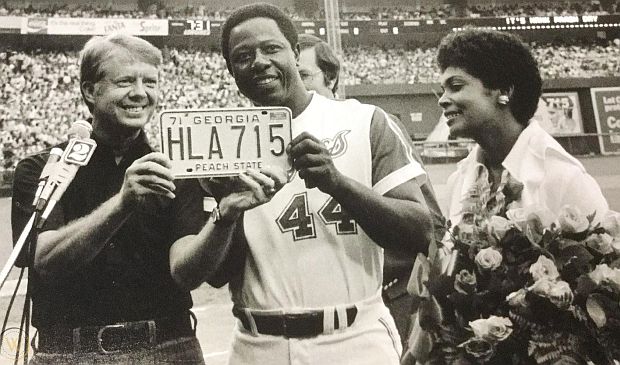

Among notables attending the game that night at Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium was Sammy Davis, Jr. and Atlanta’s black mayor, Maynard Jackson. Pearl Bailey had sung the national anthem. Also attending was Georgia Governor, Jimmy Carter, along with mother Lillian and wife Rosalynn. During a ceremony honoring Aaron, Carter presented him with a personalized Georgia license plate that read: “HLA-715,” referring to Aaron’s initials, “Henry Louis Aaron,” and the record-breaking home run, No. 715. Carter was a baseball fan, and had been following Aaron’s career, and was also on hand earlier, during a September 27, 1973 game, when he visited Aaron briefly in the clubhouse. According to Carter, he and Aaron became friends and would also learn to ski together on trips to Colorado. After Carter was elected president in 1976, he invited Aaron and Billye to the White House.

As part of festivities honoring Henry Aaron for his career home run record ( here with his wife Billye), Georgia Governor Jimmy Carter presented him with a personalized Georgia license plate that read: "HLA-715," referring to Aaron’s initials – “Henry Louis Aaron” – and the record-breaking home run, No. 715.

Henry Aaron would finish the 1974 season with 20 home runs, bringing his career total then to 733. He contemplated retirement at that point, since his Atlanta contract expired at season’s end. Yet he indicated he was willing to play another year or so. He was also interested in working in baseball management, and the Braves did offer him a job in public relations. Aaron, however, wanted a more substantive role, or possibly one evaluating baseball talent.

|

”Home Run Henry” Home Run No. 1 |

Then in November 1974, an old friend, Bud Selig, owner of the Milwaukee Brewers in the American League, made a trade with the Braves that brought Aaron to the Brewers, where an old teammate, Del Crandall, was then manager. Aaron signed a two-year contract with the Brewers for $240,000 per year and played mostly as a “designated hitter,” without having to play in the field. And with the Brewers, he continued to push his home run total up a bit, and also set another hitting record. On May 1, 1975, Aaron broke baseball’s all-time RBI record – also previously held by Babe Ruth – with 2,213 RBIs.

Aaron believed runs batted in – RBIs – were an important measure of a hitter’s worth. “I’ve always felt driving in runs was a solid measure of your worth to the team,” he told Los Angeles Times reporter Jim Murray in February 1987. “I know I used to feel embarrassed if I left runners on second or third with less than two out… I always felt ashamed to leave runners on…” It was like failing in his responsibility as a hitter, he would say. “…I wasn’t up there to keep a rally going, or get on base for the big guys. I was the big guy. I had to find a way to bring those runs in.” And more often than not, he did just that. Yet it was the home run mark for which he would be most remembered, though his RBI record may never be broken.

Still, the way he compiled his home run record was both consistent and dazzling. For 20 years in a row – encompassing seasons 1955 through 1974 – he hit 20 or more home runs every year. He had at least 30 home runs a year in 15 of those seasons. Eight times he hit 40 or more, with his high of 47 home runs coming in 1971. He is the only MLB player to have to hit 30 or more home runs a season at least fifteen times.

Henry Aaron hit his 755th and final home run with the Milwaukee Brewers on July 20, 1976, at Milwaukee County Stadium which stood for 31 years as the MLB career home run record until it was broken in 2007 by Barry Bonds. Over the course of his record-breaking 23-year career, Aaron averaged 163 hits, 32 home runs, and 99 RBIs every year. He also had a lifetime batting average of .305.

At his retirement from baseball following the 1976 season, Henry Aaron held a slew of records, among them: most home runs, 755; most RBIs, 2,297; most total bases, 6,856; most games played , 3,298; most at-bats, 12,364; and most plate appearances at 13,941. He was also at that time, second in hits at 3,771 behind only Ty Cobb. As of March 2021, he was still the career leader in total bases and RBIs, second in home runs, and third in hits, behind Pete Rose and Cobb.

Aaron appeared in a record 24 All-Star Games, won batting titles in 1956 and 1959, MVP in 1957, and led the league in home runs four times. He was the first player in baseball history to amass 500 career home runs and 3,000 hits. He is also, as of March 2021, one of only three players – Willie Mays and Albert Pujols being the others – who have managed a .300 or better batting average, 3,000 or more hits, and 600 or more home runs.

The Lasting Scar

Yet it was the Babe Ruth home run chase of the 1972-74 period that had been Henry Aaron’s most hurtful season; a time that wounded him deeply and left a lasting scar. He didn’t always show it or dwell on it, or wear it on his sleeve. Yes, he would talk about it when asked; what had happened to him in those years – and earlier – was wrong and unjust. Throughout his 23-year career, hundreds of racial slurs, slights, and cuts had come his way. But he bore much of it inside, where it ate at him in memory – especially the letters during the Ruth chase – as these had ruined his dream and left him with a hurtful view of America and baseball.

September 2013. Henry Aaron, his face still kindly and open, during interview at Turner Field in Atlanta with the Academy of Achievement, during which he noted having “a really bad time” of it for two years with hate mail, death threats, and some press accounts during the home run chase.

As the 20th anniversary of his passing Babe Ruth and setting the career home run record approached in 1994, he was interviewed by sports columnist William C. Rhoden of the New York Times:

“…April 8, 1974, really led up to turning me off on baseball… It really made me see for the first time a clear picture of what this country is about… My kids had to live like they were in prison because of kidnap threats, and I had to live like a pig in a slaughter camp. I had to duck. I had to go out the back door of the ball parks. I had to have a police escort with me all the time. I was getting threatening letters every single day. All of these things have put a bad taste in my mouth, and it won’t go away. They carved a piece of my heart away.”

Similarly, in a 2006 interview with American History magazine, Aaron again described those effects:

“It still hurts a little bit inside because I think it has chipped away at a part of my life that I will never have again. I didn’t enjoy myself. It was hard for me to enjoy something that I think I worked very hard for. God had given me the ability to play baseball, and people in this country kind of chipped away at me. So it was tough. And all of those things happened simply because I was a Black person.”

Still, life went on for Henry Aaron after his active baseball years. When he left the game in 1976 he was still in his 40s, and he had another lifetime ahead.

Later Life

1997 copy of Atlanta Braves fan magazine featuring Ted Tuner and Hank Aaron on cover for opening of Turner Field, with the street address, “755 Hank Aaron Drive”. Click for Turner's story.

“When I bought the team, naturally I wanted Henry. It was the right thing to do because he was so important to the Braves… I asked him what he wanted to do and he told me he wanted to be farm director because that was a job with some teeth. I didn’t worry about whether he could do the job. I didn’t know very much about baseball when I came in. If I could go from non-baseball person to owner, he could go from baseball player to the front office…”

In the position as director of minor-league personnel Aaron would oversee the 125 players through the Braves’ five minor league clubs. He would be paid fifty thousand dollars annually. And in that position, Aaron became the first black ex–major-league player making front-office player-personnel decisions for a major-league club. According to Bryant, Turner told Aaron he would have a job for life with the Braves. Turner would also bring Aaron into the corporate world with later positions on the boards of directors of TBS, the Braves, the Atlanta Falcons football team, the Atlanta Technical Institute, and Medallion Financial Corporation.

In the baseball legends world, meanwhile, Henry Aaron was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1982, his first year of eligibility, with a near-unanimous vote, receiving 406 of the 415 votes cast.

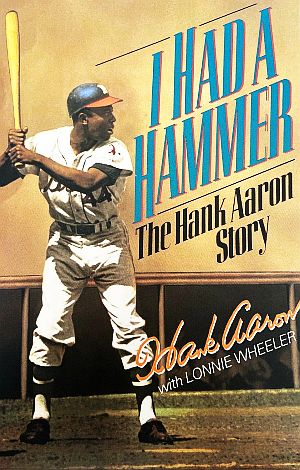

Cover of 1991 Hank Aaron autobiography, “I Had A Hammer,” with Lonnie Wheeler. Harper-Collins, 333pp. Click for copy

In 1995, a documentary film on Aaron’s life and the home run chase, was made, titled, Hank Aaron: Chasing the Dream. The film was executive produced by a team that included actor Denzel Washington and was written and directed by Mike Tollin. The film was broadcast on TBS cable TV and later made available in VHS format. Writing a review for the Baltimore Sun in 1995, Milton Kent noted, “Chasing the Dream is true must-see television, not only for baseball fans, but also for anyone with a conscience.” The film was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature and it also won a Peabody Award.

Meanwhile, the “Chasing The Dream” theme would be used by Aaron in subsequent projects, most notably for his Chasing The Dream Foundation, established in 1995 to help young people achieve their dreams through various funding, mentoring, and scholarship programs, some in conjunction with Boys & Girls Clubs of America and others with MLB funding support. In 2009, the Baseball Hall of Fame created a “Chasing The Dream” exhibit on Aaron’s life and baseball accomplishments, one of only a few such programs on an individual player at the Hall.

In April 1997, a new baseball park, named Hank Aaron Stadium, was built for the AA Mobile Bay Bears in Aaron’s hometown of Mobile, Alabama.

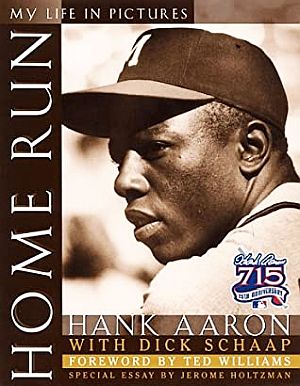

In 1999, Henry Aaron had an especially good year, beginning with his 65th birthday celebration in February at the Hyatt Regency in Atlanta. It was VIP event, including a surprise visit from sitting president Bill Clinton, who regaled the audience with the story of how Henry Aaron helped him win the Georgia Democratic primary in 1992, a victory that helped send Clinton to the White House. Another big honor that year for Aaron, also unveiled at the birthday party, was Major League Baseball’s creation of the Hank Aaron Award, an annual award given to the best hitters in the American and National Leagues. The Hank Aaron Award for hitters was meant to be the equivalent of the Cy Young Award for pitchers. When MLB rolled out the award there was also some media promotion, which included a book on Aaron, Home Run: My Life in Pictures, written by Aaron with Dick Schaap and a foreword by Ted Williams.

Howard Bryant’s 2010 book, “The Last Hero: A Life of Henry Aaron” (Pantheon, 624pp). Click for copy.

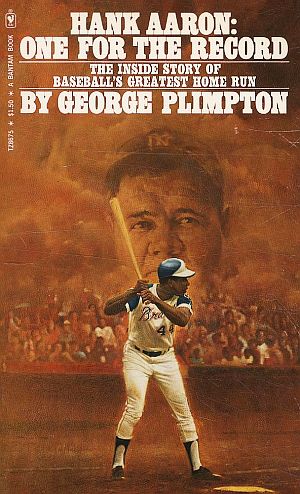

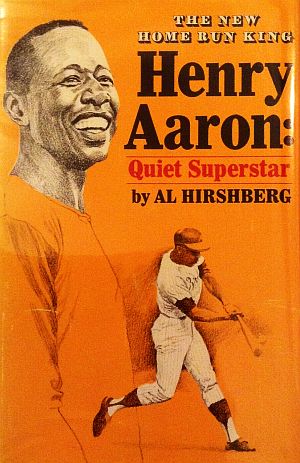

There had also been earlier books on Aaron up through 1974. One by George Plimpton: Hank Aaron: One for the Record – The Inside Story of Baseball’s Greatest Home Run (Bantam, 153pp, later updated by Little, Brown, 208pp). Another 1974 book, billed as an autobiography, Aaron, was written by Aaron with Furman Bisher (Ty Crowell Co, 236pp). However, in recent years, Howard Bryant’s 2010 book is regarded by many to be the most thorough and probing work on Aaron so far.

Henry Aaron had come to baseball from the segregated south and a family life where his mother and father had instilled in him the virtues of hard work and also the cautions of staying within the safety bounds of the southern culture he lived in — i.e, knowing one’s place, not drawing attention to oneself, etc. Throughout his baseball career, he had been cautious, private, and not self-promoting — including with the press, which some reporters took as stand-offishness, describing him in their stories unfairly or inaccurately. Henry just believed in dong his job and doing it well. He wasn’t a show-horse. But on top of his Jim Crow southern enculturation came the 1972-74 hate mail that burnished a legacy on his personality that left him looking over his shoulder for years and scanning large crowds for possible trouble to come. Still, he had set out on a Jackie Robinson-inspired mission to make things better for blacks in baseball at all levels, and beyond that, to help children going forward in their own lifetimes. And on both counts, he opened doors and created opportunities.

Over the years, Henry Aaron received all manner of achievement, civic, and civil rights awards. In 1976, he was awarded the NAACP’s Spingarn Medal. In 1977, he received the American Academy of Achievement’s Golden Plate Award. He was awarded the Presidential Citizens Medal by President Bill Clinton in January 2001; the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor, by President George W. Bush in June 2002; and in November 2015, was one of the five inaugural recipients of the Portrait of a Nation Prize, an award and national portrait granted by the National Portrait Gallery in recognition of “exemplary achievements in the fields of civil rights, business, entertainment, science, and sports.”

April 1999: “Atlanta Magazine” ran a feature piece on Henry Aaron at the 25th anniversary of his breaking Ruth’s record, focusing on his history, his personality, how fans & press perceived him, his work ethic, and more.

In the business world, meanwhile, Aaron would do quite well for himself and his family. While he had made some investment mistakes in his younger years, he came to own Hank Aaron BMW of south Atlanta as well as Mini, Land Rover, Toyota, Hyundai, and Honda dealerships throughout Georgia, as part of the Hank Aaron Automotive Group. By 2007, he sold all but one of these. He also owned a chain of 30 restaurants around the country and some apparel stores. In his years after baseball, Henry Aaron had become a wealthy man – worth $25 million by some estimates. Yet, he was also focused on leveraging his name and good fortune to helping others.

At his death in January 2021 at age 86, the tributes from those who knew him left no doubt that Henry Aaron, while a complicated man, was a giant in the important social and civil rights work he had chosen for himself both during and after his baseball years.

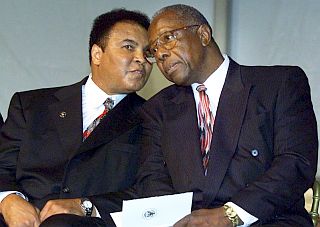

Muhammad Ali and Henry Aaron during the Presidential Citizens Medal ceremony on January 8, 2001 at the White House with President Bill Clinton.

Additional baseball history at this website can be found at “Baseball Stories, 1900s-2000s,” a topics page with links to more than a dozen baseball-related stories, including one on Jackie Robinson.

For sports generally, see the “Annals of Sport” category page. There is also a topics page on “Civil Rights Stories.” And history on Ted Turner is found at “Ted Turner & CNN: 1980s & 1990s”.

Thanks for visiting — and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research and writing at this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle.

|

Please Support Thank You |

____________________________________

Date Posted: 15 March 2021

Last Update: 1 April 2024

Comments to: jackdoyle47@gmail.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “A Season of Hurt: Aaron Chasing Ruth,”

PopHistoryDig.com, March 15, 2021.

____________________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

Henry Aaron picking out a bat in the prime of his career. |

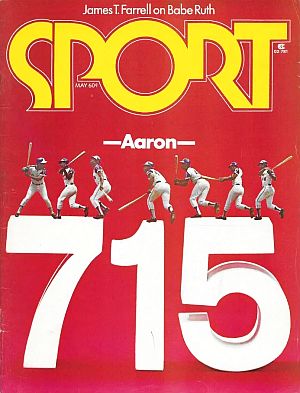

May 1974. Sport magazine, “Aaron 715,” celebrating Henry Aaron's historic, record-setting home run. |

Young Henry Aaron, coiled and ready to strike. |

April 1963 photo of Henry Aaron completing swing for a home run at the Polo Grounds as Aaron, NY Mets pitcher, Roger Craig, and umpire watch its flight. Neil Leifer photo. |

Aug 1963: H. Aaron being congratulated by teammates after hitting a Grand Slam home run off Los Angeles Dodger’s pitcher Don Drysdale. Braves won, 5-3 / UPI. |

“Hank Aaron: 1957 Topps,” PSAcard.com.

“Hank Aaron,” Wikipedia.org.

“Hank Aaron,” Baseball-Reference.com.

“Hank Aaron Named Top 1952 Rookie in Northern League; Eau Claire Shortstop Far in Front,” The Fargo Forum (Fargo, North Dakota), August 28, 1952.

Furman Bisher, “Born to Play Ball,” Saturday Evening Post, August 25, 1956.

“Hank Aaron,” Baseball Hall of Fame, BaseballHall.org.

Geoffrey C. Ward and Ken Burns, Baseball: An Illustrated History, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1994, pp. 428-431.

“Newspaper Clippings Archive”(1953-1965), MilwaukeeBraves.info.

Roy Terrell, “Murder with a Blunt Instrument. The Culprit Is Hank Aaron, Chief Pennant Hope of the Milwaukee Braves, Who Has Been Called the Killer of All Pitchers. At 23, ‘Mr. Wrists’ is the League’s Best Right-Handed Hitter Since Hornsby,” Sports Illustrated, August 12, 1957.

Alan Cohen, “September 23, 1957: Hank Aaron’s Walk-Off Home Run Gives Milwaukee Braves the Flag,” Society for American Baseball Research / SABR.org.

“Negro Stars Key To Pennant Races in Both Leagues” (Aaron cover photo with 5 others), Jet Magazine, April 16, 1959.

Associated Press, “Aaron Predicts Batting Title With .350 Mark,” Stevens Point Daily Journal (Stevens Point, WI), April 30, 1959.

Mort J. Sullivan, UPI (Milwaukee, Wis.), “Hank Aaron Goes to Bat For Kennedy,” 1960.

“Portrait of a Hitter: Hank Aaron Sees the Ball Come off the Bat,” Look, July 19, 1960.

Bob Wolf, “Braves Negroes Not Satisfied; Spring Training Housing Leaves Plenty to Be Desired, They Say,” Milwaukee Journal, March, 3, 1961.

“Hank Aaron Reveals His Hitting Secrets,” Sport (cover photo & story), July 1962.

Whitney M. Young, Jr.,”Can a Negro Play Ball in Atlanta?” New York World Telegram, November 5, 1964 (also appearing elsewhere in Young’s “To Be Equal” newspaper column under the tile, “Hank Aaron’s Choice.”).

Associated Press (New York), “Braves’ Director Favor Move to Atlanta; Milwaukee Citizens Oppose Shift: National League Okay Expected,” The Lima News (Lima, Ohio), October 22, 1964.

UPI, “Aaron, Maye Opposed to Playing in South,” The Lima News (Lima, Ohio), October 22, 1964.

“Persuading the Milwaukee Braves to Become the Atlanta Braves,” October-November 1964 Documents and Letters, Ivan Allen Digital Archive, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, GA.

Hank Aaron With Jerome Holtzman, “I Could Do the Job; The Braves’ Star Names the Negroes—and Includes Himself—Who Could Manage in the Major Leagues. He Also Discusses the Problems They Might Have.” Sport, October 1965.

Ken Hartnett, AP, “Fans’ Tribute Shakes Mathews, Aaron,” Appleton Post Crescent (Appleton, WI), September 23, 1965.

Jack Mann, “Danger With a Double A. Unhappily for National League Pitchers, Neither the Move to Atlanta Nor His 13 Years in the League Has Changed Bad Henry Aaron a Bit. He Just Keeps Swinging—and Connecting,” Sports Illustrated, August 1, 1966.

“Hank Aaron: What It’s Like To be A Neglected Superstar,” Sport, July 1968.

Al Hirshberg, Henry Aaron: Quiet Superstar, New York: G. P. Putnam & Sons, 1969.

“Hank Aaron Joins The 3,000 Hit Club” (cover photo surrounded by 8 other legends), Sports Illustrated, May 25, 1970.

Gregory H. Wolf, “May 17, 1970: Hammerin’ Hank Aaron collects 3,000th hit,” Society for American Baseball Research / SABR.org.

William Leggett, “Henry Raps One for History” (3,000th hit, cover story), Sports Illustrated, May 25, 1970, pp. 30-32.

James Toback, “Henry Aaron: The Finest Hours of a Quiet Legend,” The Sport Special, Sport(magazine), August 1970.

“Baseball’s $100,000 a Year Superstars” (cover photo with others), Ebony, June 1970.

Mickey Mantle (as told to John Devaney), “The American League’s 9 Most Underrated Players,” Sport, August 1970, pp.22-24.

Herschel Niessenson, AP, “600th Homer for Hammerin Henry,” The Evening Telegram (Herkimer, NY), April 28, 1971.

Baseball Roundup, “Hank Aaron and Willie Mays: Last of the Big Bats” (cover photo with Willie Mays), em>Ebony, June, 1971.

Craig Muder, “Aaron Begins Chase of Babe with 600th Home Run,” BaseballHall.org.

“Ruth’s Rival: Atlanta’s Henry Aaron” w/cover photo, Sporting News, July 29, 1972.

William Leggett, “A Tortured Road to 715,” Sports Illustrated, May 28, 1973, pp. 28–35.

Tom Buckley, “All Eyes on Aaron’s Assault On Ruth Home-Run Record,” New York Times, July 26, 1973.

“Catching Up With the Babe” (Henry Aaron batting photo on cover), Ebony, September 1973.

Associated Press, “Aaron Homers Off Astros, Needs Two to Tie Ruth,” New York Times, September 23, 1973.

“Hank Aaron Signs $1 Million Promotion Pact With TV Firm,” The Journal-Register (Medina, NY), January 22, 1974.

Larry Bump, “Comparison Not For Hank Aaron,” Democrat and Chronicle (Rochester, NY), January 24, 1974.

William T. Brown, “The Pursuit Resumes. As The 1974 Season Opens, Hank Aaron Will Be Ready to Close the Final Gap in His Long Chase After Ruth’s Home Run Record,” Baseball Digest, April 1974.

Michael Hinkelman Coming: Mr. 715. This Is the Season—Probably the Month—When Aaron, at 40, Takes a Moon Walk above One of the Most Hallowed Individual Records in American Sport, the 714 Home Runs Hit by George Herman Ruth,” AtlantaMagazine .com, April 1, 1974.

Dave Anderson, “Aaron Ties Babe Ruth With 714th Homer; First-Inning Drive in Season Opener Equals Record,” New York Times, Friday, April 5, 1974, p. 1.

Wayne Minshew, “Aaron Hammers No 715 And Moves Ahead of Ruth,” The Atlanta Constitution, April 9, 1974, p.1.

Joseph Durso, “Aaron Hits 715th, Passes Babe Ruth,” New York Times, April 9, 1974, p. 1.

“Aaron Blasts 715th Homer in Atlanta and Breaks Ruth’s Record; Jammed Park Goes Wild Over His Historic Clout” (Sports page headline), New York Times, April 9, 1974, p. 49.

Will Grimsley, “Humble Hank Minimizes Historic 715th Homer,” The Hunstville Times (Huntsville, Alabama), April 9, 1974, p. 1.

D. L. Stanley, “Aaron Feat Thrills Nation. All Ages Hail Super Gentleman,” The Atlanta Inquirer, April 13, 1974.

“The Hank Aaron Nobody Knows” (cover with wife Billye), Ebony, July 1974.

Pat Jordan, A False Spring, New York: Dodd, Mead, 1975.

“Highest Paid Black Athletes” (cover with Muhammad Ali, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, and O.J. Simpson), Ebony, May 1975.

Jim Murray, “Driving Home Aaron’s Legacy; He Excelled in All Facets of the Game, But the Admirable Machine-Like Great Was Best Defined by the RBI,” Los Angeles Times, February 8, 1987 (reprinted January 23, 2021).

Jim Naughton, “Hank Aaron, Beyond the Fences,” WashingtonPost.com, June 29, 1987.

Ira Berkow, “Hank Aaron Still Wields a Hammer,” New York Times, February 24, 1991.

Letters-to-the-Editor, “Ruth vs. Aaron: Beat Goes On,” New York Times, March 24, 1991.

Mike Capuzzo, Knight-Ridder Newspapers, “`Hammer’ With Axe To Grind — As We Recall Babe, Aaron Recalls Threats,” Seattle Times, April 19, 1992.

Mike Capuzzo, “A Prisoner of Memory. Eighteen Years After He Broke Babe Ruth’s Home Run Record, Henry Aaron Can’t Forget the Racist Threats That Haunted His Quest,” Sports Ilustrated, December 7, 1992.

William C. Rhoden, Sports of The Times, “The Hammer Is a Year Older,” New York Times, February 5, 1994.

William C. Rhoden, Sports of The Times, “It Is Time We Took Aaron Into Our Hearts,” New York Times, April 9, 1995.

Carl T. Rowan, “Racial Lessons From the Hank Aaron Story,” The Baltimore Sun, April 10, 1995.

Milton Kent, “Aaron Film Should Not Be Missed,” Baltimore Sun, April 12, 1995.

Lee Walburn, “Regarding Henry,” Atlanta Magazine.com, April 1999.

Tom Stanton, Hank Aaron and the Home Run That Changed America, New York: William Morrow, 2004.

Dennis Yuhasz, “Hank Aaron Biography,” Baseball-Almanac.com, 2005.

George F. Will, “The Dignified Slugger From Mobile,” WashingtonPost.com, Sunday, May 6, 2007.

“Hank Aaron’s Career Timeline,” MLB.com, May 22, 2007.

“In Honor of Hank Aaron’s 755 Steroid-Free Home Runs,” 755HomeRuns.com.

Dwight Garner, Books of The Times / Review of The Last Hero, “The Man Who Broke Babe’s Record,” New York Times, May 9, 2010.

Gary D’Amato, “Seasons of Greatness: Top 10 > No. 2: Hank Aaron, 1957. Aaron Did it All for ’57 Braves,” Journal-Sentinal/JSonline .com (Milwaukee, WI), February 26, 2012.

Larry Granillo, “How a 39-Year-Old Hank Aaron Surprised Everyone,” SBnation.com, July 4, 2013.

“Hank Aaron: Baseball Immortal,” Interview at Turner Field, Atlanta GA, Achievement.org, September 10, 2013.

Jen Christensen, “Besting Ruth, Beating Hate: How Hank Aaron Made Baseball History,” CNN.com, April 2014.

David Jackson, “Carter Hails Aaron on Anniversary of 715th Home Run, USA Today, April 9, 2014.

“Black History: Aaron, Henry Louis,” Birm-inghamTimes.com, February 19, 2015.

“The Hank Aaron Fan’s Guide to Magazine Collecting,” jasoncards.WordPress.com, Mar. 20, 2015.

Mike Dyer Hank, “Aaron Reflects on His 3,000th Hit in Cincinnati,” Cincinnati Enquirer / cincinnati.com, April 17, 2015.

“We Still Hate Hank Aaron!,” HateMail .WordPress.com, December 8, 2015.

Rhiannon Walker, “MLB vs. Florida: When the League Protested Segregated Living Quarters During Spring Training. Hank Aaron, Frank Robinson and More Spoke out to Create a Standoff Between Mlb and the State of Florida,” TheUndefeated.com, March 7, 2018.

Chris Anderson, “When Hank Aaron Lived in a Segregated Bradenton,” HeraldTribune.com (Sarasota, FL), March 11, 2019.

Frank Drouzas, “Baseball and Biscuits and Gravy: Bay Area Racism and the National Pastime,” TheWeekly Challenger.com, July 11, 2019.

“Hank Aaron,” Encyclopedia.com.

Richard Goldstein, “Hank Aaron, Home Run King Who Defied Racism, Dies at 86. He Held the Most Celebrated Record in Sports for More than 30 Years,” New York Times, January 22, 2021.

“A Quiet Life of Loud Home Runs: Hank Aaron in Photographs: The Slugging Outfielder Was a Rock of Consistency for 23 Seasons. He Was a Superstar Unlike Any Before Him — or Any Since,” New York Times, January 23, 2021.

Henry Grabar, “The Woman Who Read Hank Aaron’s Hate Mail. In 1973, the Baseball Legend Got 900,000 Letters. It Was Carla Koplin Cohn’s Job to Report the Threats to the FBI,” Slate.com, January 22, 2021.

“A Timeline of Hank Aaron’s Life and Career,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette / Post-Gazette.com), January 22, 2021.

Richard Friedman, “Macon Native Carla Cohn Reflects on Long-Time Bond With ‘Uncle Henry’ Hank Aaron,” Southern Jewish Life /sjlmag.com, January 24, 2021.

“Hank Aaron Letters, 1973, 1979,” Baseball Hall.org (collection of six letters written to Hank Aaron in 1973 and 1979).

“Henry ‘Hank’ Aaron,” MyBlackHistory.net.

Dave Sheinin and Matt Bonesteel, ‘A Giant Presence’: Hank Aaron Remembered for Towering Baseball Achievements, Cultural Impact,” WashingtonPost.com, January 22, 2021.

“Photos: The Life and Career of Hank Aaron,” WashingtonPost.com, January 22, 2021.