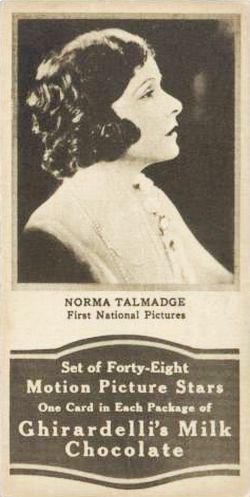

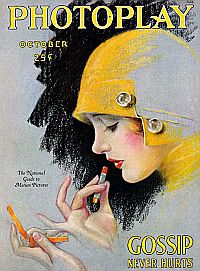

Silent screen star Norma Talmadge, shown on the December 1929 cover of Photoplay magazine, became something less of a star after the onset of sound & the “talkies.” Click for 'The Talmadge Girls' book.

Photoplay was founded in Chicago in 1911 and reached its zenith in the 1920s and 1930s, becoming quite influential in the early film industry. The magazine was renowned for its beautiful cover portraits of film stars by artists such as Rolf Armstrong, Earl Christy, and Charles Sheldon. By 1937, however, with the advancement of color photography, the magazine began using photographs of the stars.

Talmadge, shown here in an Earl Christy rendering, was one of a number of Hollywood stars whose careers were dramatically altered by the coming of “talking motion pictures.”

Photoplay’s cover story of December 1929 dealt with the hot topic of the new technology then upsetting the status quo in Hollywood, as one of the taglines explains: “The Microphone — The Terror of The Studios.”

Photoplay’s editors added another tagline on the cover’s lower right hand corner: “You Can’t Get Away With It In Hollywood” — meaning that the days of “image only” appeal for Hollywood’s big stars were over. And for those involved in film at that time, this change was truly a terror.

“It was a dreadful time, believe me,” explained actress Myrna Loy to New York Times writer Guy Flatley in 1977, then writing a magazine piece at the 50th anniversary of sound in film. “There was panic everywhere,” said Loy, “and a lot of people said, ‘This is ridiculous! Who wants to hear people talk?'” Loy added that many people at the time still “loved the silent film, the great art of pantomime perfected by the comedians and by [director, D.W.] Griffith.” So much of what happened with the coming of sound “was terribly unfair,” Loy charged. The studios, she believed, “should have taken the time to train those people whose voices didn’t match their screen images….”And indeed, for actors and actresses like Norma Talmadge, shown on Photoplay’s cover, the problem was the sound of their voices. Often, it seemed, the image and voice didn’t match up to what audiences had already cast in their minds and expected, and that’s what touched off the panic among many actors and actresses, ruining some careers. But it wasn’t just the movie stars with funny voices, explains Guy Flatley in his 1977 piece:

“Everyone was affected: actors, directors, studio chiefs, cameramen. For many the sound of the talkies was the sound of doom: Lionized stars, suddenly forced to speak, found their careers screeching to a halt. “Lionized stars, suddenly forced to speak, found their careers screeching to a halt.” – Guy Flatley Directors accustomed to shouting orders to actors at the peak of a crucial scene heard themselves being shushed by the newly all-powerful sound technicians. Studio moguls who had reigned with supreme tyrannical confidence crumbled behind doors in solitary panic, frightened by the vast sums gambling on “talkies” required.

…Cameras could no longer move freely, since the cameraman was now cramped into a huge soundproof booth, his camera robbed of almost all action. Even the scripts were different; tea-cup dramas, literal and static translations of Broadway plays initially dominated sound films…”

“Singin’ in the Rain”

Gene Kelly & Jean Hagen as Lina Lamont in hilarious ‘sound check’ scene from film ‘Singin' in The Rain.’ Click on photo to see YouTube video.

Norma Talmadge

Norma Talmadge got her start in the movie business as a model for illustrated slides — the still images projected on movie house screens in the early days of film “singalongs.” Her first silent film role came in 1911 with Vitagraph Studios of Brooklyn, New York when she played a seamstress in A Tale of Two Cities. With good looks and talent, plus a mother who helped promote her, Norma Talmadge rose to become a leading-lady of the silent screen. A marriage to influential movie executive Joseph M. Schenck also helped, as Talmadge was set up in her own film company.Talmadge became known for her dramatic roles — the “two-hankie” weepers, as some were called. A big hit came with Kiki in 1926. But in 1929, after Norma ventured into her roles in talking pictures, a reversal of fortune set in. Norma Talmadge had a flat Brooklyn accent, and when this became clear with the talkies, it surprised audiences and was greatly at odds with her glamorous, big screen personality. “Norma got a coach, but as soon as she tackled sound, she realized she’d come a cropper,” recalled screenwriter Anita Loos, who knew Talmadge and had worked with D.W. Griffith and other directors. “…But Norma had made over $5 million in silents,” noted Loos, “and was married to Joe Schenck, a multimillionaire. So it was no tragedy.”

Norma Talmadge on set of “Du Barry, Woman of Passion,” 1930.

Norma Talmadge wasn’t the only Hollywood star done in by the coming of sound. Dolores Costello, Corinne Griffith, May McAvoy, Charles Farrell, John Gilbert, and Marie Prevost, were among silent stars whose careers were ruined, shortened, or made difficult by the coming of sound. Other Hollywood hands — directors, writers, actors, etc., — had experiences, good and bad, with the silent-to-sound transition in film making. What follows below is a sampling of actors and directors offering their recollections and views on that changing era and difficult time in the film business.

Frank Capra

Famous film director Frank Capra was right on the cusp of the silent-to-sound era. He worked as a prop man in silent films and also wrote and directed silent film comedies starring Harry Langdon and the Our Gang kids. Capra worked for Mack Sennett in 1924 and then moved to Columbia Pictures. He became famous for his own feature films of the 1930s and 1940s, among them: Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (1936), Lost Horizon (1937), Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939), Meet John Doe (1941), It Happened One Night (1941), and It’s a Wonderful Life (1946). In 1977, Capra’s views and recollections of the coming of sound to film were recounted with Guy Flatley in the New York Times. “…When film found its larynx,” Capra said, “it astonished, amazed and absolutely threw everyone into a tailspin.” There was panic all around Hollywood, he explained. The studios were being asked to spend millions of dollars to revise everything. “…When film found its larynx, it astonished, amazed and absolutely threw everyone into a tailspin. There was panic all around Hollywood…”

– Frank Capra “…Men like L. B. Mayer, powerful men who were in the habit of telling everyone in Hollywood what to do, were suddenly sitting in their offices, completely stunned. They didn’t understand what the hell was going on, and so they lost control of the studio to the engineers. Soon the soundmen were telling everyone what to do…”

But the real chaos, said Capra, was among the actors. “It was easy enough to accommodate those who had experience on stage,” he said, “but no film actor had ever learned lines before.” Working on a completely silent set was another experience most film makers and actors had never had. “In the silent days,” said Capra, “the cameraman was yelling, carpenters were hammering and a director was shouting commands on the next set. Then, all of a sudden, everything had to be as silent as a tomb. It was scary. The poor actors sweated, missed their lines, cried and broke down.”

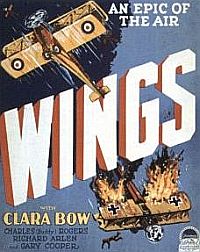

Buddy Rogers in "Wings," 1927.

Buddy Rogers

Charles Edward “Buddy” Rogers was born in 1904 in Olathe, Kansas. He became an American actor and jazz musician. He found his way into film when he was in college.

“I was studying journalism at the University of Kansas when Paramount came through looking for 10 boys and 10 girls to put together a Paramount School of Acting out at Astoria [Queens],” he later told the New York Times. “They taught us how to roll down a flight of stairs without hurting ourselves, how to wear false beards and how to hold a kiss for three minutes without laughing.”

In the mid-1920s, Rogers began acting professionally in Hollywood films. A talented trombonist, and skilled on several other musical instruments, Rogers performed with his own jazz band in motion pictures and on radio.

Buddy Rogers starred in the 1927 silent film “Wings,” which won the first ever Best Picture award. Click for film.

“…To find out how the public would react to my voice, the studio put me in a movie called ‘Varsity,’ in which I was the star football player. It had a 12-minute talking sequence, and I don’t mind telling you those were pretty serious moments for me. It worked out fine, and, of course, we had our voice coaches with whom we’d meet regularly so they could teach us how to ‘e-nun-ci-ate’. They also brought out a lot of people from the New York stage, actors who knew how to project their voices — people like Ruth Chatterton and Clive Brook. They were very cool to us. All of us were at the mercy of the soundman; the director had lost control…”

In 1937, Rogers became the third husband of silent film legend Mary Pickford, a woman twelve years his senior. The couple had two children. Rogers continued his work in film for many years. He died of natural causes in Rancho Mirage, California in 1999 at the age of 94.

Wallace Beery, an actor from the silent film era, initially had trouble remembering lines. But he became a Top Ten box office draw, here with young Jackie Cooper in 1931's ‘The Champ,’ for which Beery won Best Actor. Click for film.

Walsh on Beery

Raoul Walsh, an early stage actor in New York city in 1909, became a director whose numerous films spanned the silent-to-sound era.

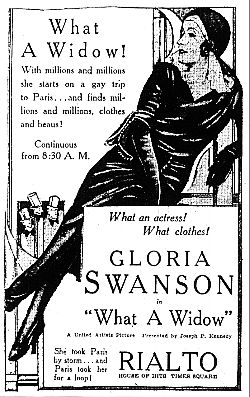

In 1914, Walsh went west with D. W. Griffith, and became a director of silent films such as Regeneration (1915), The Thief of Bagdad (1924), What Price Glory, and others. He also directed early talkies, including The Big Trail (1930), and other films such as They Drive by Night (1940), They Died with Their Boots On (1941), and White Heat (1949). Walsh worked with a range of actors and actresses over the period, from Gloria Swanson, Anna May Wong, and Douglas Fairbanks, to a young John Wayne, Wallace Beery, Marlene Dietrich, George Raft, Ida Lupina, Edward G. Robinson, James Cagney, Errol Flyn and others.

In 1977, Walsh recalled the transition from silent film to sound in Guy Flately’s New York Times piece. “I knew we’d have problems when the actors had to learn lines,” he explained. “They had drama coaches, of course. I don’t know if they had conducted classes in a subway before they came west, or what, but I do know they were terrible. One of the actors who had a hard time was Wally Beery. He got the dialogue all backwards, so he just started ad-libbing. Some of what he said turned out good, but some had to be cut out…” Beery, however, was one of those actors who successfully weathered the silent-to-sound film era, in fact, becoming one the Top Ten box office draws in the early sound era, and winning an academy award for his performance in the 1931 film, The Champ. Beery was also among the stars in Walsh’s 1933 film, The Bowery.

Allan Dwan

Allan Dwan, a Canadian film director, directed his first movie, Rattlesnake and Gunpowder, in 1909. After making a series of westerns and comedies, he directed fellow Canadian Mary Pickford in several very successful movies. He also worked with actors Douglas Fairbanks and Gloria Swanson during the heyday of silent film, including the acclaimed 1922 version of Robin Hood with Fairbanks in the title role.

Allan Dwan, seated left, on a movie set in the silent film era with Gloria Swanson, center, possibly in the 1910s-1920s. Click for book on Allan Dwan.

Dwan recalled the surprises and perils that could come in the early days of sound recording: “…Once, I was making a picture with Doug [Fairbanks ] — a big picture that cost over a million — and I was getting worried. It was just about the last silent movie made, and all around us sound was drifting in. I advised Doug that our movie should be made with a speaking prologue and epilogue. He agreed, but to my horror, Doug — who had a good voice — came up sounding like a tinhorn tenor. The soundmen hadn’t checked for decibels, so another man, with a deeper voice, read the prologue and epilogue, and the audiences accepted it as Doug.”

Dolores Costello, film studio photo.

Dolores Costello, born in 1903, was an American film actress who achieved her greatest success during the era of silent movies. Sometimes described as “delicately beautiful,” Costello was a blonde-haired actress who became nicknamed “The Goddess of the Silent Screen.” With her sister, she had appeared on Broadway in the 1920s, leading to a contract with Warner Brothers. After several small parts in feature films, she starred opposite John Barrymore in an adaptation of Moby-Dick titled The Sea Beast (1926). Warner Brothers soon began starring her in her own films, alternating her roles in contemporary stories and elaborate costume dramas. In 1927, she and John Barrymore starred in When a Man Loves. She and Barrymore became romantically involved and married in 1928. She became the mother of John Drew Barrymore and the grandmother of Drew Barrymore.

Dolores Costello, Photoplay cover, Oct 1927. Artist: Charles Sheldon.

“Magnificent thing that she is… she’s got something in her voice that Terrible Mike simply snarls out loud about… Headed for the heights she was, until she played in ‘Glorious Betsy.’ Poor Dolores — there are two opinions in Hollywood as to what her mike voice sounded like. One clique says it sounded like the barking of a lonesome puppy; the other claimed it reminded them of the time they sang ‘In the Shade of the Old Apple Tree’ through tissue paper folded over a comb. . . It’s not Dolores’s fault; it’s just one of the Terrible Mike’s dirty tricks.”

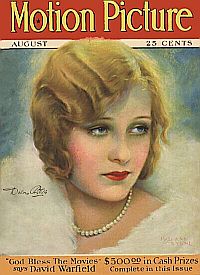

Dolores Costello on the cover of “Motion Picture,” Aug 1928. Artist Marland Stone.

King Vidor

Late 1920s studio ad touting King Vidor’s ‘Big Parade’ & others. Click for DVD.

Vidor’s long experience with silent and sound film left him with a certain perspective. He recalled that there was more going on with the “silents” than most realized, and that a certain attentiveness was required of film viewers that made the experience different than what it would later become. Vidor also argued that the silents summoned a special kind of talent and expression from its actors, and the productions generally became a unique art form. And for a time, the coming of sound was a disruptive force, he found, in the evolution of acting and filming techniques. Here’s Vidor making those comments:

“…We call them silent, but all the films in those days were played with an orchestra or an organ or piano. They never played silently. …. [I]n silent theaters there was none of this popcorn stuff, this running out to the lobby for food and drink that’s done all the time now. We had to glue our attention to the screen…

“Naturally, I believe in progress, and it’s hard to say that movies were better in the silent days. But I can remember a distinct feeling I had in the late 20’s, along with directors like Clarence Brown and Henry King, that we had achieved an art form that was unique. We felt we were bursting forth with a fresh channel of expression in each new movie. Silent techniques constituted a universal language; Chaplin, after all, was the best known man in the whole world. Then, bang, we were hit with this sound thing, and the technicians began to dominate the scene. ‘You can’t do that, you can’t move there, you can’t speak with your head down.’“It was a good 10 or 15 years before we got back to where we had been at the peak of the silent film — the mobility and expressionism that the silent camera had achieved. In the beginning, we figured that sound would be good for singing and dancing, since musicals were kind of unreal anyway. But we didn’t see the need for it in drama. The minute dialogue came in, we were conscious of what was going to happen to the universal appeal of movies. Everything became too specific, and everyone had to speak in a certain manner…”

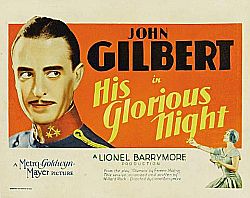

John Gilbert

Actor John Gilbert, 1920s.

Screenwriter Anita Loos had a somewhat different take on the Gilbert affair: “Lillian Gish told me… that Louis B. Mayer did Jack Gilbert in on purpose. Jack was getting so much money that they were looking for a way to break his contract with MGM. So Mayer told the sound technicians to manipulate things so that Jack’s voice would come out funny.” Gilbert was indeed one of the highest paid actors of his day, and one of the screen’s most magnetic personalities, garnering $250,000 per film. He had appeared in more than 100 films. But with the onset of sound, and how audiences perceived him thereafter, he was unable to gain his former big star status. Descending into alcoholism, he later died of a massive heart attack in Los Angeles in early 1936. He was 36 years old.

Out With the Old

During the silent-to-sound transition in Hollywood, there was a gradual changing of the guard, with many actors and actresses leaving their careers for a variety of reasons, not all of which were due to voice issues and the new technology. However, with the popularity of the sound picture, audiences perceived certain silent-era stars as old-fashioned, Some actors were pushed out by the studios, then using voice issues as an excuse to fire or demote them for other reasons.even those who had no voice problems. Some actors, such as Lillian Gish, went back to the stage, while others left acting entirely. Among the latter were: Colleen Moore, Gloria Swanson, Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford. Some were pushed out by the studios, then using voice issues as an excuse to fire or demote them for other reasons. Louise Brooks was more or less given an ultimatum by one Paramount studio chief who used her voice as a vague threat as to why she might not make the cut, and so, was undeserving of a salary increase. He told Brooks she could take lower pay or quit. She chose the latter, even though her contract had specified a salary increase. Clara Bow left acting too, with her speaking voice sometimes cited as the cause, when actually it was more likely her freewheeling Hollywood lifestyle that grated on some studio executives.

There was also a shift in Hollywood hiring. Demand rose for directors who understood the power of the spoken word and had experience in the theater, leading the studios to recruit directors and actors from New York’s Broadway. Stage actors experienced with dialogue were also hired in large numbers during the 1930s. Several of the new medium’s biggest attractions came from vaudeville and the musical theater, bringing performers such as Al Jolson, Eddie Cantor, Jeanette MacDonald, and the Marx Brothers. Edward G. Robinson, Humphrey Bogart, Paul Muni, Melvyn Douglas, Leslie Howard, and Katharine Hepburn were also among those who came to film from the stage. And the plays themselves were also acquired by the studios to be turned into films. More than 25 percent of the plays produced during the 1930s were bought by the film studios. Sound also helped change the structure of the film business leading to consolidation and the growth of the best positioned companies.

The first “all talking” feature film -- “Lights Of New York” – came from Warner Brothers in July 1928. It became one of that era’s most profitable films, then grossing $1.3 million. Click for DVD.

In January 1928, there were approximately 20,000 theaters across the U.S., but only 157 of them had been renovated for sound. Studio moguls were not happy with the money needed to equip Hollywood’s production studios for sound, or to put the new equipment into thousands of theaters. At the studios, silent films that had already been shot, were given inserted segments of quickly-recorded dialogue so they could be billed as “new talkies.” Enthusiastic public demand for talkies pushed theaters to install new sound equipment. As 1929 drew to an end, 8,741 movie houses were equipped for sound. Movie attendance increased to 110 million, almost double the movie attendance in 1927. Still, for a time, many studios produced both silent and sound versions of their films, as many theaters, especially in rural areas, could not afford the conversion. The studios, in any case, did quite well.

In 1928 and 1929, the profits of Warner Brothers, Fox, and Loew’s/MGM, all surged sharply upward. Warners’ profits surged from $2 million to $14 million; Paramount’s rose by $7 million, Fox’s by $3.5 million, and Loew’s/MGM’s by $3 million. A new player in the business named RKO — which hadn’t even existed in September 1928 — became one of America’s leading entertainment companies by the end of 1929. However, most independent studios couldn’t compete with the four major studios in the production of sound films. In fact, the combination of sound’s expense and the Great Depression would lead to a wholesale shakeout in the film industry, leaving essentially five big integrated companies — MGM, Paramount, Fox, Warner Brothers, and RKO — and three smaller studios — Columbia, Universal, and United Artists. These eight studios would dominate the film industry through the 1950s.

MGM's “The Broadway Melody” of Feb 1929 was the first smash-hit talkie from a studio other than Warner Bros. and the first sound film to win a “Best Picture” Oscar. Click for DVD.

Please visit the “Film & Hollywood” and/or “Celebrities & Icons” category pages at this website to find other stories about Hollywood and film stars, or go to the Home Page or the Archive for additional stories. Thanks for visiting — and if you like what you see here, please make a donation to help support the research and writing at this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

__________________________________

Date Posted: 19 October 2010

Last Update: 14 May 2021

Comments to: jdoyle@pophistorydig.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Talkie Terror, 1928-1930,”

PopHistoryDig.com, October 19, 2010.

__________________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

“Griffith Foresees Sound Movie Supreme; Says Talkie Will Force Drama and Silent Picture Off Stage in Five Years,”New York Times, Friday, February 22, 1929, p. 17.

“Britons Debate Value of Talking Pictures; London Times Criticizes Them, But Theatres Where They Are Being Shown Are Packed,” New York Times, Wednesday, April 3, 1929, p. 22.

“Projection Jottings; Cyril Maude’s Ideas on Dialogue Films– Miss Talmadge’s New Picture,” New York Times, Sunday, May 18, 1930, Section: Arts & Leisure, p. X-5.

Harry Carr, “Mike, the Demon Who Sends the Vocally Unfit Screaming or Lisping from the Lots,” Photoplay, December 1929.

“Mary Garden Sees Opera’s Doom Soon; Technical Resources of the Talkies, She Says, Will Prove Superior to Stage…,”New York Times, Tuesday, October 14, 1930, p. 28.

“Joy v. Monopoly,” Time, Monday, November 17, 1930.

Guy Flatley, “The Sound That Shook Hollywood; On The 50th Anniversary of the Talkies, Survivors of the Silent Film Era Recall The Panic of ’27,” The New York Times Magazine, Sunday, September 25, 1977, p. 213.

David W. Menefee, The First Female Stars: Women of the Silent Era, 2004.

Hal Erickson, “Norma Talmadge,” All Movie Guide.

“1920’s Ghirardelli’s Milk Chocolate Cards,” Things-and-Other-Stuff.com

Old Film Star & Studio Photos, TheStarLight Studio.com.

“Gloria Swanson,” Wikipedia.org.

Anita Loos, The Talmadge Girls, New York: Viking Press, 1978, 204 pp. Click for copy.

“Vintage: Ads For Artists, Part 3,” All Movie Talk, April 26, 2007.

“Dolores Costello,” Allure, Saturday, April 19, 2008.

“Frank Capra,” Wikipedia.org.

“Silents to Talkies,” FrancescaMiller.com.

“Charles Rogers (actor),” Wikipedia.org.

Robert Benchley, “Enter The Talkies,” From the Archives (1928), The New Yorker, March 21, 1994, p. 100.

“Raoul Walsh,” Wikipedia.org.

Carlo Schindler, Garbo & Gilbert in Love: Hollywood’s First Great Celebrity Couple, London, Orion Publishing Group, 2005, 304 pp.

“Wallace Beery,” All Movie Guide.

Dave Harris, “Original Movie Ads of Lost Films,” MissingFilm.com, 2005.

Donald Stenn, Clara Bow: Runnin’ Wild, New York: Doubleday, 1988, 338 pp.

Jonas Nordin, “The First Talkie,” TalkieKing, Friday, February 27, 2009.

“Sound Film,” Wikipedia.org.