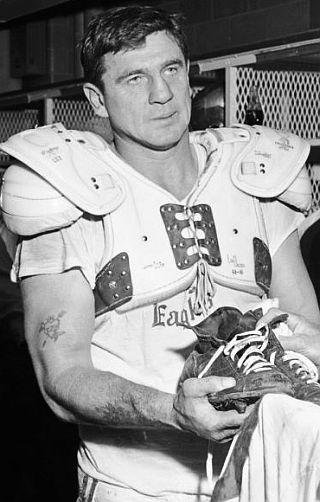

Chuck Bednarik, age 37, handing in his spikes and jersey for team history after his final Eagles game, November 1962.

Charles Philip Bednarik was born in May 1925. His parents emigrated to the U.S. from eastern Slovakia in 1920 looking for a better life. They settled in the Pennsylvania town of Bethlehem, where Chuck’s father began working in the steel mills stoking the open hearth furnaces at the Bethlehem Steel Company.

As a boy, Bednarik attended a Slovak parochial school in Bethlehem where Slovak was the language of instruction. The second oldest of six children, Bednarik was raised three blocks from Lehigh University, where he attended football games and wrestling events.

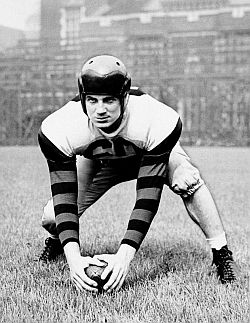

At Bethlehem’s Liberty High School he began playing football, and in 1942, his junior year, Bednarik helped Liberty to an undefeated season and became an All-American high school center. In the classroom, Bednarik was a vocational-technical student studying electrical work, and had figured he’d follow his father to work in the Bethlehem Steel mills.

Chuck Bednarik, circled above and enlarged below, in WWII-era photo with his B-24 crew. |

Chuck Bednarik was 19 years old when he enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Corps. |

Oct. 27th, 1946: University of Pennsylvania's Chuck Bednarik named Lineman of the Week in Associated Press players poll (AP photo). |

Following graduation, however, he entered the U. S. Army Air Force and served as a B-24 waist-gunner with the Eighth Air Force. During WWII, Bednarik flew on 30 combat missions over Germany, for which he was awarded four Oak Leaf Clusters, among other medals for his service. “How we survived, I don’t know,” he would often say in wonderment in later talks with reporters.

“The anti-aircraft fire would be all around us,” Bednarik recounted to Sports Illustrated’s John Schulian in a 1993 interview. “It was so thick you could walk on it. And you could hear it penetrating. Ping! Ping! Ping! Here you are, this wild, dumb kid, you didn’t think you were afraid of anything, and now, every time you take off, you’re convinced this is it, you’re gonna be ashes.”

After the war, Bednarik, who had previously thought of following his father into the steel mills, was instead encouraged by his high school football coach, John Butler, to go to college. Butler believed Bednarik could get an athletic scholarship, and after Butler arranged a meeting with the coach at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, Bednarik enrolled there.

At Penn

At Penn, he became a three-time All-American football player, and a “two-way” man, excelling at both center on offense and linebacker on defense. He was also used occasionally as a punter. Beginning in 1946, Bednarik started at center and linebacker for Penn for three seasons.

In those years, Penn was a national football power, drawing crowds in excess of 70,000. For most of that time Penn was the second-best team in the East, behind the legendary Army teams with stars such as Glenn Davis and “Doc” Blanchard.

Bednarik was named first team All-America his final two seasons at Penn. He has also pressed found memories of his playing career at Penn.

“I could relive Franklin Field forever” Bednarik would later say. “Every Saturday, 78,800 people. It was unbelievable, the crowds that we had.”

A collegiate All-American at center, he also excelled at linebacker, and proved to be a nimble defender. He intercepted seven passes in 1946 and six more the following year. In 1948, he was named the College Player of the Year by a number of organizations.

Bednarik won the Maxwell Award in 1948, given to the best collegiate player of the year. He also finished third in Heisman Trophy voting that year, just one of five offensive lineman in the history of the award to do so.

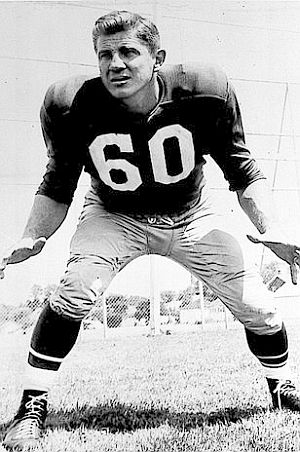

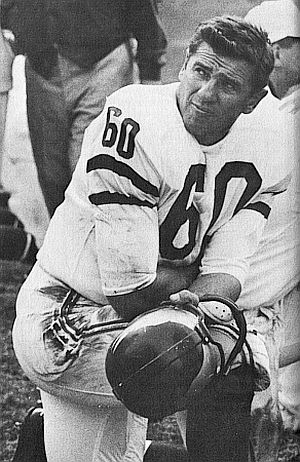

Chuck Bednarik strikes a linebacker pose in a early 1960s Philadelphia Eagles’ player photo. |

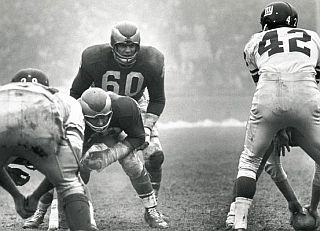

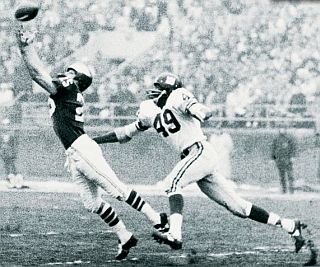

Chuck Bednarik, No. 60, at linebacker going for the ball on a pass play to a Green Bay Packer receiver. |

Drafted By Eagles

In 1949, he was the first player taken in the professional National Football League draft, selected by the Philadelphia Eagles. As a rookie with the Eagles, he alternated starting at linebacker and center. In that season, the Eagles won the 1949 league championship game, defeating the Los Angeles Rams 14-0.

Bednarik played 14 seasons with the Eagles, from 1949 through 1962. In those years he rose to mythic, “iron man” stature, noted for his durability as a two-way man, both a powerful blocker on offense and fierce tackler at linebacker. He missed only three games in his 14 years with the Eagles.

11 Times All-Pro

Bednarik was named All-Pro eleven times, and was the last man to play both offense and defense for an entire game in the National Football League. Upon retirement, he was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1967, his first year of eligibility.

During the years he played with the Eagles, the club had its ups and downs. In 1952,1953 and 1954 the Eagles finished in the upper tier of their conference with season records of 7-5-0, 7-4-1, and 7-4-1. Bednarik’s play during these years was outstanding.

In 1953, Bednarik intercepted a career-high six passes, then a high number for a middle linebacker. In the Pro Bowl that year, he was voted the player of the game.

But from 1955 through 1958 the Eagles failed to post a winning season. At the end of the 1958 season Bednarik announced he was quitting, but soon thought better of it and returned to the Eagles. With a family of four daughters by then, Bednarik needed the money.

By 1959, the Eagles went 7 and 5, and things were looking better heading into 1960, when Bednarik would have what some consider his best season. That year proved to be the magical season for the Eagles; they notched a 10 and 2 record and won the NFL championship, beating Vince Lombardi’s Green Bay Packers with standouts Bart Starr, Paul Hornung and Jim Taylor. In 1961, the Eagles continued their winning ways, going 10 and 4. But in 1962, they finished in 7th place with a dismal 3-10-1 record, and that’s when Bednarik retired – this time for good.

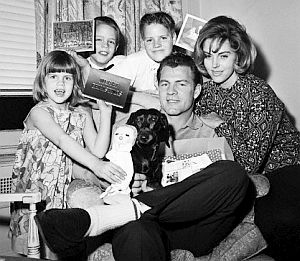

Nov 1962: Chuck Bednarik with family in Abington, PA. From left, twins Carol and Pamela 7, Donna 9, Jacquelyn 20 mos., wife Emma, and Charlene 12. AP photo.

“Concrete Charlie”

Hugh Brown, a sports writer for The Philadelphia Bulletin, who covered the Eagles, once wrote that Bednarik was as tough as the concrete he sold, referring to a another job Bednarik held at the time, adding the nickname “Concrete Charlie.”

It was not uncommon during the 1950s and early 1960s for pro football players to have a full-time job away from the sport, as football salaries were not then the lucrative millions they are today. Bednarik, like others, worked another job to help support his family.

A routine day during the season back then called for a team meeting at 9 a.m., practice from 10:30 to about noon. After lunch, Bednarik would then begin his second job as a salesman for the Ready-Mix Concrete Co., which later became the Warner Company. But the nickname Brown had come up stuck, as some used it in the context of Bednarik’s bone-crushing tackles at his day job.

Chuck Bednarik at his Hall of Fame induction, August 1967.

As an Eagle linebacker, he was not only a stalwart in stopping the run, but a nimble pass defender as well, snagging 20 interceptions during his 14-year NFL career.

On August 5, 1967, Bednarik was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame. In the years following his Hall of Fame induction, Bednarik would collect other awards and honors. In 1969, he was named center on the all-time NFL team and was also added that year to the College Football Hall of Fame.

In 1987, the Philadelphia Eagles retired his No. 60 numeral, one of only eight numbers retired in the history of the Eagles franchise. In 2010, Bednarik was ranked 35th on the NFL Network’s “Top 100” greatest players.

Chuck Bednarik, No. 60, at his linebacker post in a game against the New York Giants.

Spoke His Mind

In his retirement years, Bednarik at times would be outspoken, offering controversial and sometimes caustic comment about the current state of the game, certain players, and/or Philadelphia Eagles management and owners. Still, for the most part, he remained a revered figure among Philadelphia sports buffs, especially those of “old school” vintage.

During his tenure at linebacker, Chuck Bednarik faced many noteworthy and talented opponents – among them, some of the game’s all-time great running backs such as Jim Brown, Jim Taylor, and Paul Hornung. Frank Gifford, another among the all-time greats, was also one of Bednarik’s worthy adversaries, and the two had met in some memorable scrums, not the least of which was one on November 20th, 1960 at Yankee Stadium; a confrontation that is explored in more detail a bit later. But first, a look at Mr. Gifford’s football vitae.

Frank Gifford

Oct 1951: USC’s Frank Gifford making a big gain against the Univ of California Bears.

While Frank was growing up, the Giffords lived in 47 different towns before he started high school. “I don’t remember completing a single grade in the same grammar school,” Gifford would later say.

It was in Bakersfield, California that Frank finally settled into high school and began to try his hand at football. He went out for the lightweight football team as a freshman, but he was just 5 foot 2 inches and 115 pounds and didn’t make it.

As a sophomore, he tried for the varsity, but played on the lightweight team as a third-string end. And he wasn’t much of student then either. But between his sophomore and junior years, he filled out, and made the varsity team.

When Bakersfield lost its starting quarterback to an automobile accident, Gifford replaced him. Along with friend and teammate, Bob Karpe, Gifford helped lead the 1947 Bakersfield “Drillers” to a Central Valley title. College scouts had come around by then, as well, but Gifford’s grades were terrible.

With the help of high school coach Homer Beaty, Gifford headed to Bakersfield Junior College as a stepping stone to the University of Southern California (USC). He became a Junior College All-American football player at Bakersfield College and then went on to USC where he would become an All-American performer.

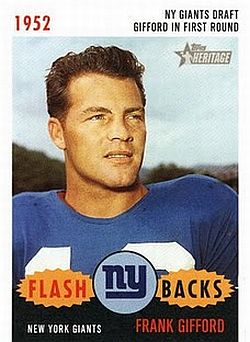

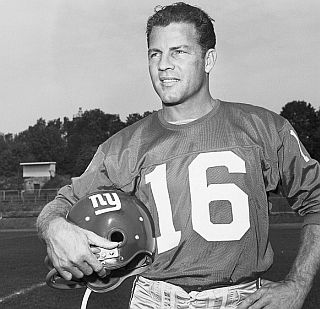

Frank Gifford was selected by the NY Giants in the first round of the 1952 draft.

“Mr. Football”

In the late 1940’s, early 1950’s, Gifford was “Mr. Football” at Southern Cal, playing both offense and defense. He played three varsity years at USC, 1949-1951. In 1951, he alternated at quarterback, half-back, and fullback, punted, and place-kicked. That year he rushed for 841 yards, and rolled up 1,144 yards in total offense, also kicking field goals on occasion. In mid-October that year, Gifford and USC were nationally ranked at No. 11, as they came to play the University of California, then ranked No. 1. California got off to a 14-0 lead. But Gifford proved the difference in the final outcome. He scored on a 69-yard run, threw a touchdown pass, and with five minutes to play, led a drive that won the game 21-14. Gifford’s All American honors in 1951 came mostly for his offensive running and passing, but he also excelled on defense. In one the game against Navy he had two interceptions.

Gifford turned pro in 1952 when he was selected in the first round of the player draft by the New York Giants, where he would play his entire career. He also married that year, at the age of 22, to Maxine Ewart and the couple would have three children together. With the Giants, Gifford at first, like Bednarik, was a “two-way” man, playing both running back on offense and defensive back. In later years he would move primarily to offense as a flanker back/wide receiver. In the late 1950s, he was also considered briefly for the quarterback slot when the Giants were having some uncertainty at that position. But it was from his halfback position that Frank Gifford became something of triple threat, as he could run, throw, or catch. When the Giant’s offensive coordinator, Vince Lombardi, introduced the halfback option, Gifford was well suited to the role.

Frank Gifford was regarded as an explosive, open-field runner, capable of long gains and quick scores, both as a receiver and a through-the-line halfback.

“But no defense ever wanted to see the former USC star carrying the ball in the open field,” says the Bleacher Report. For Gifford “turned short passes into 77-yard scores, turned quick hand-offs into 79-yard gains, and from the backfield [he] was a danger to throw his famous jump pass.”

Gifford attempted just 63 passes in his career, but since 14 of his passes went for scores (including an 83-yard bomb to Eddie Price), he was, according to Bleacher Report, one of the most dangerous triple threats in NFL history.

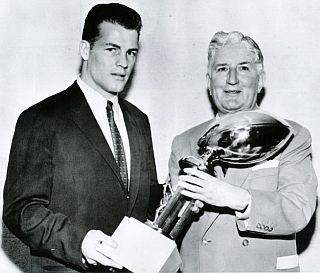

Frank Gifford receiving the NFL’s MVP trophy for 1956.

Gifford was an eight-time Pro Bowl selection, named at three positions: running back, wide receiver and defensive back. He also had five trips to the NFL Championship Game. Gifford’s biggest season may have been 1956, when he won the Most Valuable Player award of the NFL, led the Giants to the NFL title over the Chicago Bears. Gifford also played in the famous December 1958 championship game between the New York Giants and the Baltimore Colts, a game that many believe ushered in the modern era of big time, television-hyped, pro football. He would also write a book about that game many years later.

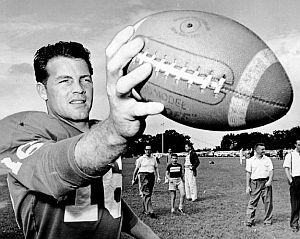

Frank Gifford in light New York Giants workout attire, 1963.

Gifford’s good looks and affable manner gained him entrée to radio and television, and as a sports celebrity sponsor for print and TV advertising. In the 1950s and 1960s during his active playing years he modeled Jantzen swimwear and clothing lines along with fellow pro athletes, appearing in a series of print ads. He also began sports broadcasting on radio and television while still an active player, first on CBS, then later after retirement, for ABC. In 1971 he became a regular on ABC-TV, with Monday Night Football and Wide World of Sports, as well as occasional specials and guest hosting appearances. He would also write, or co-author, several books on football. See “Celebrity Gifford” story at this website for more on Gifford’s film, TV, and sportscasting career.

Frank Gifford is also credited with a somewhat famous quote about the game: “Pro football is like nuclear warfare,” he is reported to have said, “There are no winners, only survivors” – attributed to him via Sports Illustrated, July 1960. That quote would have special meaning for Frank Gifford after one famous 1960 encounter with Chuck Bednarik and the Philadelphia Eagles.

November 1960

Eagles vs. Giants

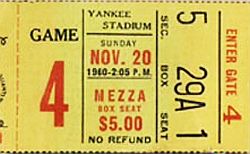

Ticket stub: NYGiants - Phila. Eagles football game of Nov 20, 1960, Yankee Stadium.

Coming into the game, the Giants were 5-1-1 while the Eagles were 6-1-0, each with five games remaining, and each with a possible shot at the NFL’s Eastern Conference Championship. So the outcome of this game would be important.

Philadelphia that season had lost its opening-day game to the Cleveland Browns, 41–24. But after that, they were unbeatable, winning their next six games in a row. The Giants had lost only one game by then, as well.

Tommy McDonald, No. 25, of the Philadelphia Eagles, was one of the team's top players in 1960. |

Nov. 1962: NY Giants defensive lineman, from left: Andy Robustelli, Dick Modzelewski, Jim Katcavage and Rosey Grier, were also on the team in 1960. Photo Dan Rubin. |

The Eagles and Giants teams of 1960 had many high caliber players between them. In addition to Bednarik at center and linebacker, the Eagles’ offense included quarterback Norm Van Brocklin, Tommy McDonald at flanker back/wide receiver, Pete Retzlaff at end, defensive lineman Marion Campbell, linebacker Chuck Webber, and defensive backs Tom Brookshier, Don Burroughs, and Maxie Baughan.

The New York Giants’ roster that year included notable linebacker, Sam Huff, quarterbacks Charlie Conerly and George Shaw, halfback and receiver Kyle Rote, defensive linemen Andy Robustelli and Roosevelt “Rosey” Grier, running backs Mel Triplett and Alex Webster, kicker, Pat Summerall, and offensive tackle Rosey Brown. Some of these Giants had also played on the 1956 team that won the NFL championship that year, as well as the 1958 and 1959 teams that had won the Eastern Conference.

But the November 20th, 1960 Giants-Eagles game would determine which team would hold first place in the Eastern Conference at that time.

In the early going, the Giants scored first with a Joe Morrison one-yard run in the first quarter, followed by a Pat Summerall point-after kick. Summerall added 3 more points with a 26-yard field goal in the 2nd quarter. The Giants led, 10-0. In the 3rd quarter, Eagles’s quarterback Norm Van Brocklin threw a 35-yard completion and touchdown pass to Tommy McDonald, followed by Bobby Walston kick. New York 10, Eagles 7. In the 4th quarter, the Eagles’ Bobby Walston kicked a 12-yard field goal, tying the score, 10-10. Then the Eagles took the lead after Eagles corner back Jimmy Carr scored on a 38-yard fumble return followed by Bobby Walston’s point-after kick. The Eagles now led, 17-10. But the fourth quarter could be decisive, and the Giants were versatile, capable of come-back play. And this is when the Bednarik-Gifford collision occurred.

Frank Meets Chuck

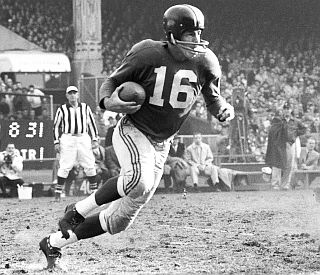

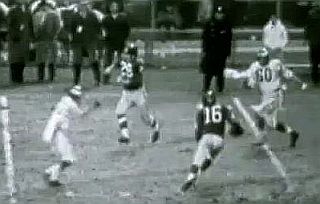

Frank Gifford, No. 16, has just taken a few steps after catching a pass over the middle, trying to avoid a downfield tackler, as No. 60, Chuck Bednarik, takes a bead on him. |

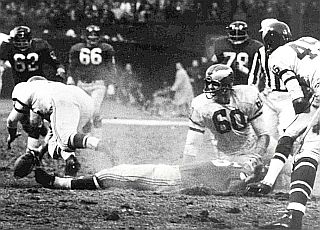

Chuck Bednarik’s tackle of Frank Gifford, as the ball pops out far right, during Eagles-Giants game of Nov 20th, 1960. |

Bednarik’s tackle of Gifford as seen from another angle, the near sideline, during Giants-Eagles game. |

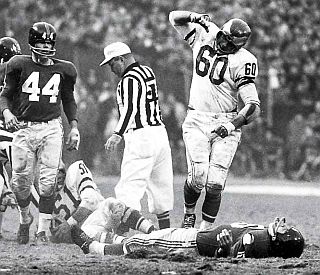

Chuck Bednarik continuing through his tackle of Frank Gifford as Gifford hits the ground. |

With Gifford stretched out on the turf, Bednarik, No. 60, looks around as Chuck Webber goes for the loose ball. |

Chuck Bednarik had jumped up after his tackle of Frank Gifford to celebrate the Eagles’ fumble recovery. |

Iconic Photo. Chuck Bednarik, No. 60, standing over NY Giants running back, Frank Gifford after famous tackle, 20 Nov 1960. Photo/ John G. Zimmerman / Sports Illustrated. |

Chuck Bednarik continuing celebration for his team’s near-certain victory while standing over Gifford. Photo/ John G. Zimmerman / Sports Illustrated. |

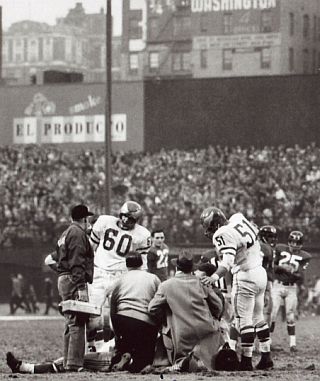

Chuck Bednarik & Chuck Webber, No. 51, hover around the injured Frank Gifford as trainers attend to him on the field. |

Frank Gifford of the New York Giants is carried off the field on a stretcher after Chuck Bednarik’s tackle. |

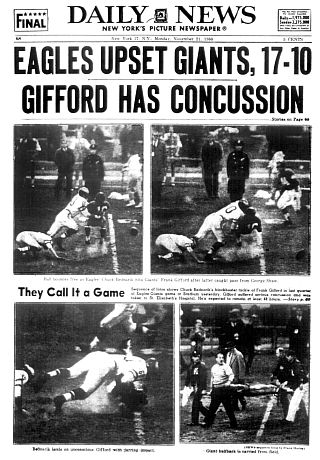

November 21st, 1960: New York Daily News full-page treatment of Eagles-Giants game with photos of the Bednarik-Gifford hit, Gifford being taken off the field by stretcher, and part of headline reading, “Gifford Has Concussion.” |

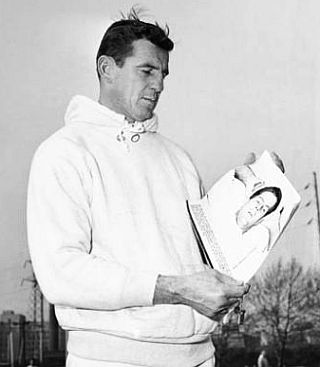

Nov 22, 1960: The Eagles' Chuck Bednarik, in light work-out clothes in Philadelphia, looks at an Associated Press photo of Frank Gifford holding an ice pack to his head in the hospital. |

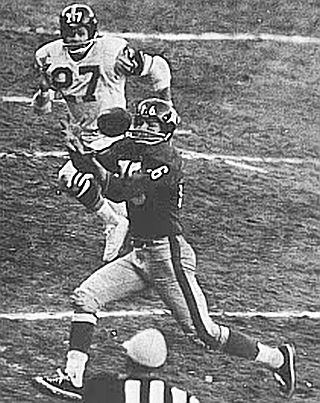

Frank Gifford would return to play for the Giants as a flanker back, 1962-1964, shown here catching a pass over the middle in a 1963 game against the Pittsburgh Steelers. |

As the Giants took the ball late in the fourth quarter with about two minutes remaining, they were on the move and looking for a potential game-tying touchdown. Frank Gifford at that point in the game had about 100 total yards rushing and receiving.

Giant’s quarterback George Shaw called the play in the huddle. At the snap of the ball, Gifford set out on his passing route, turning upfield, then cutting toward the middle of the field on a crossing pattern.

As he went, Gifford was surveying where the defenders were, later saying that he was eyeing Eagles’ safety Don Burroughs. As Gifford caught the pass from Shaw while crossing the middle of the field, he took a few steps to avoid an oncoming downfield defender. And that’s when Bednarik, No. 60, comes into the frame shown above right.

Bednarik hit Gifford full on, forcing Gifford off his feet and into the air, legs flying. Bednarik, at 6-foot-3, 230-pounds, hit Gifford, 6-foot-1, 185-pounds, shoulder high, just under the chin. Gifford, expecting to find terra firma, instead met something like a brick wall.

Following the hit, as shown on an NFL film clip, Gifford appears to go limp, as his arms splay out to his sides hitting the ground uncontrollably as he goes down.

When Bednarik hit Gifford, the ball popped out, causing a fumble, available for recovery by either team. Chuck Webber, No. 51 for the Eagles, is seen in the later photos below right recovering the fumble. A cloud of dust was still hanging in the air as Bednarik and other players looked around to get their bearings. Gifford was motionless, lying flat on his back on the field. Bednarik later recounted the scene:

“We were leading the game, and Gifford ran a down-and-in route. After he caught the ball he took two or three steps and I waffled him chest high. His head snapped back and the ball popped loose. It was retrieved by Chuck Weber [of the Eagles], and when I saw that, I turned around with a clenched fist and hollered, ‘This […expletive ] game is over!’”

The fumble, coming in the fourth quarter with little time left and the Eagles in the lead, meant that Philadelphia had won the game. The win put the Eagles 1.5 games ahead of the second-place Giants and in a good position to win the Eastern Conference.

One of the classic photographs to emerge from that moment was a Sports Illustrated photo taken by John G, Zimmerman of Bednarik standing over the prone Gifford, appearing to be celebrating over Gifford’s misfortune. The photo has become one the iconic sports photos of all time.

In some ways, the Bednarik pose and interpretation – rightly or wrongly – resembles the famous May 1965 photo of Muhammad Ali (then Cassius Clay) standing over Sonny Liston after a knock down in the world heavyweight championship fight.

Bednarik, however, has stated repeatedly that he wasn’t gloating or cerebrating about knocking Gifford out, but rather at his team’s now-certain victory with little time remaining. “I was celebrating,” Bednarik would later say. “But the reason wasn’t that he [Gifford] was down. The reason was that the hit [on Gifford, forcing the fumble] won the game.’ ”

Steve Sabol, the late president and founder of NFL Films, and the man behind the slow-motion highlight clips of NFL games that were popular for many years, had once called the Bednarik-Gifford hit, “the greatest tackle in pro football history.” Yet, for many who have seen the old black-and-white film footage of that tackle, it does not appear to be a particularly vicious hit.

However, Sabol explained in a 1994 Philadelphia Daily News story that the camera work of that day did not adequately convey the force of the blow delivered by Bednarik. “The fact that the film is black-and-white and the camera is so far away really diffuses the impact,” Sabol explained to Daily News reporter Ray Didinger. “If the same play happened now, with all our field level cameras and the field microphones to pick up the live sound, it would be incredible.”

Others who were on the field at the time of the tackle, also describe it as particularly frightening. Tom Brookshier, a former Eagles cornerback who was on the field that day, along with others, say they had never heard anything like it.

“It was not the usual thump of padded body hitting padded body. This was a sharp crack, like an axe splitting a piece of wood,” explained Ray Didinger of the Daily News, recounting what Brookshier and others had reported.

“You could hear it all over the field,” said Tom Brookshier. “As a player, it gave you a chill because it was so unusual. Then I saw Gifford on the ground, his eyes rolled up, his arms flat out. He looked like a corpse. I thought, ‘My God, this guy is dead. Charlie killed him.’ ”

Over the years, the 1960 Bednarik-Gifford collision took on a life of its own, becoming part of pro football lore. “Any other guy in any other city, it would have been just another vicious, clean play,” Bednarik said of his tackle on Gifford in a 2009 New York Daily News story. “But against Gifford in New York it took on, well, a religious air.”

Gifford in later years had become a well-known New York and national sportscaster, including a long run on the Monday Night Football program, which as Bednarik has stated, helped keep the hit alive in prime time:

“If that was Kyle Rote or Alex Webster or any other Giant [I had tackeld], it would have been forgotten long ago. But Frank’s (TV) visibility kept it alive. (Howard) Cosell talked about it for 10 years on Monday Night Football. Every time there was a hard hit, Cosell would say, ‘Just like when Chuck Bednarik blindsided you, Giff, at Yankee Stadium.’ I’d sit there on my couch and say, ‘Blindside my fanny. It was a good shot, head on.’”

And on that score, Gifford agrees, more or less. “It was perfectly legal,” Gifford would later say of Bednarik’s tackle. “If I’d had the chance, I’d have done the same thing Chuck did.”

And again, in a 2010 phone conversation with New York Times reporter Dave Anderson, Gifford reiterated that view: “Chuck hit me exactly the way I would have hit him, with his shoulder, a clean shot.”

“I sent a basket of flowers and a letter to Frank in the hospital,” Bednarik reportedly said in one interview. “I told him I’d pray for him. I’m a good Catholic, but I’m also a football player. When I was on the field, I knocked the hell out of people, but that’s the name of the game.”

Decades later, the two Hall of Famers were attending a banquet, and Bednarik greeted Gifford:

“Hey, Frank,” Bednarik said, “Good to see you. How are you doing?”

Gifford replied, “I made you famous, didn’t I, Chuck?”

“Yes, you did, Frank,” Bednarik said.

Over the years, the photo of Bednarik standing over Gifford lying on the turf has become something of collector’s item, and Bednarik has autographed a fair number of them for fans. Sports Illustrated has included the photo in its gallery, “The 100 Greatest Sports Photos of All Time.”

Gifford Comeback

Back in the 1960s, meanwhile, Gifford did not play football in 1961, the year following Bednarik’s hit. He began doing more sportscasting work with CBS that year, and it appeared his playing days were over. However, the football bug soon got the best of Gifford, as he had stayed involved with the Giants during the year as a team scout and advisor.

Each week he scouted the Giants’ upcoming opponents for strengths and weaknesses and would advise on game strategy. And sometimes during on-the- field practice sessions, Gifford would line up impersonating the next opponent. There was no contact for Gifford during these sessions. He would just run plays as a flanker.

But during that time, as he ran those plays, Gifford was doing pretty well against the Giants best defensive backs. His speed was good, often beating them as he played the week’s coming opponent. That got him thinking about coming back. He was not happy with the exit he had made after the Bednarik hit and didn’t want to end his career that way.

“I had been out for a year,” Gifford would say of his situation, “but I thought, what a terrible way to have gone out. And I thought if I don’t do it now, in 1962, I’ll never be able to.”

In 1962, Gifford would explain to Sports Illustrated reporter Tex Maule:

“I made a lot of money in the year I stayed out. I didn’t stay out because of the head injury. I had personal reasons I don’t want to go into. But I missed pro football. I don’t know any kind of business you can go into where you can get as much excitement once a week as you can get playing pro ball. Nothing you can care about as much. If you are lucky enough to be able to do this for a living, I think you should do it as long as you can.”

Dr. Francis Sweeney, team doctor for the Giants at the time, gave Gifford the go-ahead to resume playing in 1962. “He had a deep concussion,” Sweeney said in the 1962 Sports Illustrated article, adding this in his explanation: “…A severe shock [to the head ] may start a hemorrhage which can seep down into the lower parts of the brain and affect motor areas and be very serious. This is what Frank had. But once that heals, it’s completely healed and doesn’t have a carryover effect.”

[Today, the science of head injury trauma is much advanced. CTE, or Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy, is a known progressive degenerative disease of the brain found in athletes with a history of repetitive brain trauma, concussions, and even repetitive sub-concussive hits to the head. In late 2015, after his death and a post-mortem exam of his brain, Frank Gifford was found to have had CTE, which his family believes altered his behavior and cognitive skills in his later years.]

In November 1960, The New York Daily News (above right), reporting on the game and the Bednarik-Gifford hit, ran a headline which read in part, “…Gifford Has Concussion.” In addition, the New York Times and other newspapers also reported that Gifford had suffered “a deep concussion.”

Yet Gifford, in later years, had a somewhat different account of the injury. In one interview at the Bluenatic blog with Mark Weinstein in August 2013, Gifford replied:

“…Can we get this right, please? I’ve tried to do it many, many times, but it keeps coming up. It wasn’t a head injury. It was a neck injury. I got hit by Chuck Bednarik on a crossing pattern. And I went back and snapped my head back on the field, which was kind of semi-frozen. And it stunned me. I wasn’t knocked unconscious or anything, but it did stun me. It wasn’t all that serious, really, but I was going to be out the rest of the season because the doctors didn’t know quite what to do. This was before they had CAT scans, you know, so I went to have my head X-rayed, and of course my head was all right. But I took some time off and then I came back and played three more years and made the Pro Bowl at a new position, wide receiver.”

Gifford, also explained in a November 2010 New York Times article by Dave Anderson:“When I had tingling in my fingers about seven or eight years ago, I had X-rays of my neck. The technician asked me if I had ever been in an automobile accident. I told him no, but he said the X-rays showed a fracture of a neck vertebra that had healed by itself. After the Bednarik play, they never X-rayed my neck. They just X-rayed my head.” But in 1962, after 18 months away from football, Gifford’s injuries apparently had time to heal — as was thought at the time — and as he returned to training camp that year, he was cleared to play.

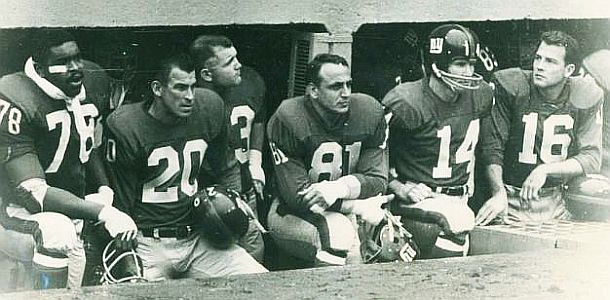

Early 1960s photo of New York Giants players in sideline dugout, believed to be, from left: Lane Howell (No. 78), Jimmy Patton (No. 20), Andy Robustelli (No. 81), Y.A. Tittle (No. 14), and Frank Gifford ( No. 16).

When Gifford came back in 1962, he was shifted to flanker back. By then, the Giants had a new quarterback, Y. A. Tittle, who had come from the San Francisco 49ers, and Tittle wasn’t sure about Gifford as a receiver. “Y. A. didn’t know me; he wasn’t throwing to me much,” Gifford explained to Dave Anderson of the New York Times. “But in our third game in Pittsburgh, Y. A. asked if I could beat defensive back Jack Butler on a fly. I dove and caught the pass for a touchdown. From that point on, he trusted me.”

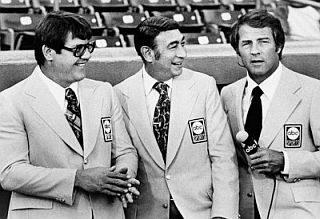

1975 “Monday Night Football” broadcast team: from left, Alex Karras, Howard Cosell, and Frank Gifford.

In retirement, Gifford continued his second career in sports broadcasting, including a 22-year run at Monday Night Football.

1976 book, “Gifford on Courage: Ten Unforgettable True Stories of Heroism in Modern Sports.”Click for copy.

Gifford in Print

Gifford also continued to appear in print and TV advertising, endorsing a variety of products. In addition, several sports books featured or included him as the principal subject or a featured player, among them: Don Smith’s book, The Frank Gifford Story (1960); William Wallace’s book, Frank Gifford: The Golden Year, 1956 (published 1969); Jack Cavanaugh’s Giants Among Men: How Robustelli, Huff, Gifford and the Giants Made New York a Football Town and Changed the NFL.(2008).

Gifford also wrote or co-authored three other books – Gifford on Courage: Ten Unforgettable True Stories of Heroism in Modern Sports (1976), with Charles Mangel; The Whole Ten Yards (1993), Gifford’s autobiography, with Newsweek’s Harry Waters; and The Glory Game: How The 1958 NFL Championship Changed Football Forever (2008), with Peter Richmond.

In the 1980s, Gifford met his third wife, Kathie Lee Johnson, a popular TV host, while he was a guest host on ABC-TV’s Good Morning America. The two were married in 1986 and would have two children together. More about Gifford’s broadcasting and advertising career is found at “Celebrity Gifford: 1950-2010s,” also at this website.

Chuck Bednarik in a rare moment on the sidelines, as he was known for his “iron man” two-way performances.

Bednarik, Pt. 2

Back in 1960, meanwhile, Chuck Bednarik and the New York Giants had another round yet to go. Due to some odd scheduling that season, the Giants and Eagles played back-to-back weeks, and on Nov 27th, 1960, they met again, this time at Franklin Field in Philadelphia. First place in the Eastern Conference was still at stake with the Giants needing a win to stay alive. New York took a 17-0 lead in that game, but the Eagles fought back behind quarterback Norm Van Brocklin to win, 31-23.

Gifford was still in the hospital from the previous week’s encounter with Bednarik, and there was some talk of possible “Giant payback” for Bednarik’s hit on Gifford. “They were rough and mean, like always,” Bednarik would later report, “but not dirty.” Sam Huff had a good hit on Bednarik in that game with a blind side block on one play. And the two traded some trash talk at the time, but nothing more.

Bednarik, in fact, made a difference in this game as he had in the November 20th game, forcing a key fumble. In the second half, the Gaints’ Charlie Conerly was at quarterback and Bednarik faked a blitz up the middle. Conerly, spooked a bit by Bednarik, pulled away from center too quickly and fumbled the snap. Bednarik’s biggest game that year, however, came in December.

Eagles coach Buck Shaw with Norm Van Brocklin & Chuck Bednarik after winning 1960 Championship.

In that game, quarterback Norm Van Brocklin, playing his last game as an Eagle, threw a 35-yard touchdown pass to Tommy McDonald in the second quarter. And again, in the fourth quarter, Van Brocklin took the Eagles on a 39-yard drive to put the Eagles up by a 17-13 count, which would prove to be the winning score.

Bednarik in that game had knocked Packer’s running back Paul Hornung out of the game with a jarring third quarter tackle. But in the fourth quarter, with the game on the line, Bart Starr threw a screen pass to their powerful fullback, Jim Taylor.

Taylor caught the ball on Philadelphia’s 23 yard line and had the end zone in sight. The Eagles’s Maxey Baughan had the first shot at him, but Taylor cut back and broke Baughan’s tackle. Then Taylor ran through Eagles safety Don Burroughs.

The 1977 book, “Bednarik: Last of the Sixty-Minute Men,” written with Jack McCallum. Click for copy.

Bednarik played 58 minutes of that game, only sitting out kickoffs, making one fumble recovery and 12 tackles. In fact, during the 1960 season by one calculation, Bednarik was on the field for some 600 of a possible 720 minutes, or more then 83 percent of the playing time that year. He was the NFL’s last two-way player over a full season.

In retirement some years later, Bednarik teamed up with writer Jack McCallum to do a 1977 book titled, Bednarik: Last of The Sixty-Minute Men.

In 1995, The Chuck Bednarik Award was established by the Maxwell Football Club of Philadelphia. The award is presented annually to the best defensive player in college football judged by NCAA head coaches, Maxwell Club members, sportswriters, and sportscasters. Past winners, for example, have included: Paul Posluszny, Penn State (twice); Julius Peppers, North Carolina; and Charles Woodson, Michigan.

In Philadelphia, meanwhile, a group of businessmen and sports fans raised some $100,000 in 2010 to commission a statue of Bednarik in his football regalia to be located at the University of Pennsylvania. Dedicated in November 2011 with the help of former Pennsylvania governor and Philadelphia mayor, Ed Rendell, that statue today stands inside Gate 2 on the North side of Franklin Field, the stadium where Bednarik played his college ball and a number of pro games with the Eagles.

Statue of Chuck Bednarik in his football regalia stands at the University of Pennsylvania’s Franklin Field, dedicated there in November 2011.

The Changing Game

The Bednarik-Gifford history in some ways is also a story about one of those transition periods of old and new; when the game of football was played differently, without all the hype it has today. Bednarik, in many ways, represented the old school, the way the game was once played – when players of the 1950s weren’t paid a lot of money, worked other jobs to make ends meet, while delivering a workman-like performance on the field. This was the era before the Super Bowl; before the media glare and pop culture focus.

Gifford, too, was of that era, but he was also one of the first, like Paul Hornung of the Green Bay Packers, on the cusp of something new, and pushing into the new era, as players who had media appeal and commercial value; players who would transition into public personas with second careers in sports media, advertising, and/or entertainment.

There is more about Gifford’s off-the-field career at “Celebrity Gifford,” a separate story at this website. See also at this website, “Dutchman’s Big Day,” about Norm Van Brocklin’s single-game passing record from 1951, which still stands today.

Additional football stories at this website include: “I Guarantee It,” covering Joe Namath’s career, some AFL-NFL history, and Namath’s famous Superbowl III prediction in 1969; and, “Slingin` Sammy,” on the career of quarterback Sammy Baugh and Washington Redskins history, 1930s-1950s. For additional story choices go to the Home Page or the Annals of Sport category page. Thanks for visiting – and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research and writing at this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

_________________________________________

Date Posted: 18 February 2014

Last Update: 11 February 2024

Comments to: jackdoyle47@gmail.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Bednarik-Gifford Lore – Football: 1950s-1960s,”

PopHistoryDig.com, February 18, 2014.

_________________________________________

Football Books at Amazon.com…

Sources, Links & Additional Information

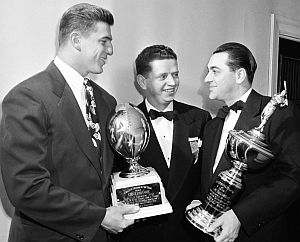

Jan 31, 1949: Chuck Bednarik, left, and Lou Boudreau of the Cleveland Indians baseball team, far right, collecting trophies for their play from the Philadelphia Sports Writers Association. Jack Wilson center (AP photo). |

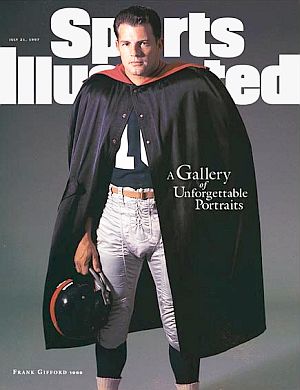

The July 21st, 1997 cover of Sports Illustrated uses a 1959 Frank Gifford photo by John Zimmerman to feature “A Gallery of Unforgettable Portraits” – a photo of Gifford that projects a certain “superman” aura about it. |

November 8, 1962: Chuck Bednarik in the snow at Yankee Stadium during a 19-14 loss to the New York Giants , the Bronx, New York. NFL photo. |

In the late 1950s, the New York Giants considered using Frank Gifford at quarterback. (NY Daily News). |

Gifford, like Bednarik, was a family man in the early 1960s, shown here with his then-wife Maxine, three children, and family pet. December 1963. |

Dec. 26th, 1960: Chuck Bednarik, # 60 walking off the field with Jim Taylor #31 & Paul Hornung #5 of Green Bay Packers after Eagles won NFL Championship game. |

“Rough Day in Berkeley: A Zany Season Reaches Climax As Southern Cal Tips California Off Top of Football Heap,” Life (with photo sequence of a Frank Gifford 69-yard run), October 29, November, 1951, pp. 22-27.

“Gifford at Quarterback For Giants in Workout,” New York Times, July 25, 1956.

“Conerly’s Pitch-Out to Gifford Rated as Key to Team’s Victory,” New York Times, October 29, 1956.

“Conference Lead Will Be at Stake; New York Will Try to Take First Place Away From Philadelphia Eleven,” New York Times, November 20, 1960.

Louis Effrat, “Run with Fumble Wins Game, 17-10; Carr of Eagles Catches Ball Dropped by Triplett and Goes for 38 Yards,” New York Times, November 21, 1960.

Robert L. Teague, “Gifford Suffers Deep Concussion; Katcavage Also Sent to Hospital, With a Shoulder Injury,” New York Times, November 21, 1960.

Louis Effrat, “Halfback Facing Stay in Hospital; Gifford Will Be Confined for Three Weeks — Katcavage Has Broken Clavicle,” New York Times, November 22, 1960.

“Giant Back Calls Consultant Who Gives Dim Report on Concussion a ‘Crepe Hanger’ — Bednarik Sends Gift,” New York Times, November 23, 1960.

Robert L. Teague, “Cowboys’ Plays Tested by Giants; Aerial Defense Is Stressed at Workout — Gifford Is Released From Hospital,” New York Times, December 2, 1960.

Tex Maule, “Then The Eagle Swooped,” Sports Illustrated, December 5, 1960.

“Chuck Bednarik Knocks Out Frank Gifford,”(NFL Videos, 14 second clip), NFL.com.

William R. Conklin, “Star Back Signed by Radio Station; Gifford Retires as Player but Giants Hope to Keep Him in Advisory Post,” New York Times, Friday, February 10, 1961.

Robert M. Lipsytet, “Gifford Returns as a Player; Giants’ Halfback, 31, Gives Up Duties as Broadcaster; Back Holds 3 Club Records,” New York Times, Tuesday, April 3, 1962, Sports, p. 48.

“Gifford Is Shifted by Football Giants,” New York Times, September 6, 1962.

Tex Maule, “No Rocking Chair For Frank Gifford,” Sports Illustrated, October 1, 1962.

Arthur Daley, “Sports of The Times; The Comeback Kid The Adjustment Long Road Back In the Homestretch,” New York Times, November 18, 1962.

“Gifford Tops ‘Comeback’ Poll,” New York Times, January 3, 1963.

John Schulian, “Concrete Charlie,” Sports Illustrated, September 6, 1993.

Frank Gifford and Harry Waters, “It’s a Helluva Town,” GQ: Gentlemen’s Quarterly, September 1993, Vol. 63 Issue 9, p. 282.

Art Cooper, Letter From the Editor-in-Chief, GQ: Gentlemen’s Quarterly, September 1993, Vol. 63 Issue 9, p. 44

Larry Stewart, “Gifford’s Life Is Now an Open Book,” Los Angeles Times, October 29, 1993.

Bill Fleischman, “Gifford’s Book Perfectly Frank,” Daily News(Philadelphia, PA) December 6, 1993.

“Chuck Bednarik Through the Years”(photo gallery), NFL.com.

“In The News: Chuck Bednarik” (a listing of stories), The Morning Call (Allentown PA).

Ray Didinger, “Mack Truck 1, VW 0, Gifford K.O. Legendary, But Bednarik Remembers Win,” Philadelphia Daily News (Phila., PA), December 14, 1994.

Dave Anderson, “Charlie Conerly, 74, Is Dead; Giants’ Quarterback in 50’s,” New York Times, February 14, 1996.

Bill Lyon, “Concrete Charlie,” When the Clock Runs Out: 20 NFL Greats Share Their Stories of Hardship and Triumph, Chicago: Triumph Books, 1999, pp. 31-48.

Paul Reinhard, “Concrete Charlie Chuck Bednarik Has Traveled A Long Way From Bethlehem’s South Side,” The Morning Call, December 12, 1999.

Chuck O’Donnell, “The Game I’ll Never Forget: Chuck Bednarik,” Football Digest, March 2001.

Ari L. Goldman, “John G. Zimmerman, 74, Leader Of Action Sports Photography,” New York Times, August 11, 2002.

Mike Kilduff, “Thawing the Ice Between Gifford and Bednarik,” Sporting News, August 25, 2003, Vol. 227, Issue 34, p.8.

Ron Flatter, “More Info on Chuck Bednarik,” ESPN.com, November 19, 2003.

Ron Flatter, “Sixty Minute Man,” ESPN.com, March 23, 2005.

Rick Van Horne, Friday Night Heroes: 100 Years of Driller Football, July 2006.

Ron Flatter, “Sixty Minute Man,” ESPN Classic, February 20, 2007.

Jack Cavanaugh, Giants Among Men: How Robustelli, Huff, Gifford and the Giants Made New York a Football Town and Changed the NFL, New York: Random House, 2008.

Hank Gola & Ralph Vacchiano, “Crushing Blows and Devastating Fumbles Mark Giant-Eagle Rivalry, Daily News, Saturday, January 10, 2009.

“Sunday, November 20, 1960: Gifford and Bednarik,” The ’60s at 50, November 20, 2010.

Dave Anderson, “A 50-Year-Old Hit That Still Echoes,” New York Times, November 20, 2010.

Adam Lazarus, “The 50 Most Explosive Players In NFL History” (No. 27: Frank Gifford, WR/RB), BleacherReport.com, February 21, 2011.

Les Bowen, “On Military Day, Bednarik Recalls Dodging Flak,” Daily News (Philadelphia, PA), Monday, August 15, 2011.

“Chuck Bednarik Statue to Be Unveiled at Franklin Field Prior to Penn-Cornell Football Game on November 19,” Almanac (University of Pennsylvania), November 8, 2011, Volume 58, No. 11.

Steven Jaffe, “Chuck Bednarik Statue Unveiled; Long-Planned Tribute to Penn Football Legend Becomes Reality at Franklin Field,” Daily Pennsylvanian, November 21, 2011,

Chris Holmes, “Life Magazine’s Look at the NFL of 1960,” Football Friday, September 28, 2012.

“Chuck Bednarik and Frank Gifford,” 100 Greatest Sports Photos of All Time (photo gallery), Sports Illustrated.

Mark Weinstein, “Frank Gifford: Icon” (Interview with Gifford), BlueNatic, Tuesday, August 20, 2013.

Ray Didinger, “Eagles History: ‘The Hit’ Still Resonates” (with video), Philadelphia Eagles .com, October 23, 2013.

“Rosey Grier and The 1960 Giants: Rare Photos,” Photo Gallery / and, “New York Giants: Rosey Grier Talks About Playing for Big Blue in 1960,” Life.com.

“Chuck Bednarik (statue) – University Of Pennsylvania” (Franklin Field – Dedicated November 19, 2011), HanlonSculpture.com.

“Chuck Bednarik,” Pro Football Hall of Fame.

“Chuck Bednarik,” Wikipedia.org.

“Frank Gifford,” Pro Football Hall of Fame.

“Frank Gifford,” Wikipedia.org.

Bob Gordon, The 1960 Philadelphia Eagles: The Team That They Said Had Nothing But a Championship, Sports Publishing, August 2001, 200 pp.

_______________________________