On March 23rd, 2005 in Texas City, Texas, a horrendous explosion and fire at the British Petroleum (BP) oil refinery killed 15 workers and injured another 180. At the time, it was one of the worst industrial accidents to have occurred in the U.S. since the late 1980s. Pat Nickerson, a veteran of the Texas City BP refinery for 28 years, was on site the day of the explosion driving his truck inside the refinery to an office trailer. “I looked down the road. It looked like fumes, like on a real hot day, you see these heat waves coming up,” he explained, describing the scene during a 60 Minutes TV interview, “and then I saw an ignition and a blast. Then my windshield shattered. The roof of the vehicle I was driving caved in on me.”

Firefighting water canons are trained on the damaged BP oil refinery in Texas City, TX in the aftermath of March 23rd, 2005 explosion & fire. Fifteen workers were killed and another 180 injured in the disaster. Photo, Brett Coomer/Houston Chronicle.

After the blast, Nickerson was still alive and he began digging through the wreckage looking for survivors. “Out of the corner of my eye, there was somebody on the ground,” he later recalled in his 60 Minutes interview. “A guy named Ryan Rodriguez, and he was just kind of staring at me. He couldn’t move because his face was so, you know, deformed and everything from the blast. And some, you know, bones and stuff that were… protruding from his chin.” Rodriguez died in the ambulance.

The refinery that day was re-starting a unit that had been down for repairs. It was a tower processing unit being filled with gasoline. Due to malfunctioning equipment and sensors, the tower overflowed with excess gas. The gas then went into a back-up unit, which also overflowed. That caused a geyser of gasoline to shoot into the air. Workers in the refinery reported seeing the cloud of the vaporizing fuel shoot from the tall stack. It then rolled down to ground level, enlarging into a massive vapor cloud as it moved, still being fed by the malfunctioning equipment.

March 23rd, 2005. BP’s Texas City, TX oil refinery as it burned following the explosion there that killed 15 workers and injured 180 in one of the worst industrial accidents in U.S. history. Photo, Galveston County Daily News, Dwight Andrews.

Some refinery workers that day would later recall hearing frantic voices calling over a hand-held radio: “Stop all hot work! Stop all hot work!” They were trying to prevent the ignition of the escaped and creeping vapor cloud. If it found any open flame – furnace burner, welding work, or even a simple spark – it would explode violently. And in that section of the refinery, there was a lot of equipment running. But the vapor cloud soon found an ignition source – believed to have been a pick-up truck whose owner was trying to move it out of the area. But the flood of hydrocarbons prevented him from starting it. Still, he continued to crank the truck’s engine, not knowing what was happening, as co-workers frantically tried to stop him. But it was too late. A spark from the engine ignited the giant gas cloud that had been forming, touching off the horrific explosions and firestorm that followed.

Map showing location of BP's Texas City, Texas refinery.

“…Once ignited, the flame rapidly spread through the flammable vapor cloud, compressing the gas ahead of it to create a blast pressure wave. Furthermore, the flame accelerated each time a combination of congestion/confinement and flammable mix allowed, greatly intensifying the blast pressure in certain areas. These intense pressure regions, or sub explosions, produced heavy structural damage locally and left a pattern of structural deformation away from the blast center in all directions.”

Eva Rowe, 20 years old, was driving to Texas City on the day of the explosion to visit her parents, both of whom worked at the refinery. “I was at a gas station about 45 minutes away,” she would later recall during a 60 Minutes TV interview. “Some man inside said that the BP refinery had exploded. I called my mom. And my mom didn’t answer, and that’s not like my mom. She always answered.” Rowe later learned that both of her parents were among the 15 people killed that day.

March 23, 2005: BP’s Texas City, Texas oil refinery continues to burn in some areas following the explosion there, as water is trained on remaining fires and hot spots. Note emergency response workers, yellow hats, lower right.

At the scene of the explosion that day, fire trucks, emergency vehicles, helicopters all descended on the site. Amid ongoing fires, blown-apart structures, and twisted steel, the search for the dead and injured at the devastated scene began. As recounted by the Houston Chronicle, David Leining, a BP employee, was inside the temporary double-wide office trailer when he heard a weird banging noise. He went to the door to look outside, and just as he did he was pushed to the ground by the force of the blast. The vapor cloud had seeped beneath the double wide office trailer. After the explosion, Leining was flat on his back beneath a pile of rubble. An unconscious co-worker was also in that same pile above him. Leining recalled that he was able to move his left hand and reach his communicator to send out a distress signal. Another worker, Ralph Dean, thrown off the seat of his forklift by the blast, but still alive, was one of the first workers in the explosion to begin digging out co-workers. He used the fork lift to dig through the rubble at the trailer site to locate Leining, but his feet were pinned by the wreckage. Dean continued using his forklift to pry away wreckage on the pile, and to haul off other dangerous debris, pushing burning vehicles, whose gas tanks were exploding, away from the remains of the trailer area.

Aerial view of blast & fire damage at BP’s Texas City, Texas refinery sometime after the March 2005 explosion and fires, showing severely damaged structure in the upper left and burnt-out hulks of several vehicles at center of photo.

As he worked clearing debris, Ralph Dean found the body of his father-in-law only a few feet from Leining. Dean later discovered his wife, Alisa, pinned under a metal bookshelf and barely alive. Also killed in the trailer that day were Morris King, who died only a few feet away from where Leining was pinned. Another colleague, Larry Thomas, who had been leaning against the trailer wall, was also killed. Leining ended up with multiple fractures in his ankles, knee problems, and permanent hearing damage. Linda Rowe, who also worked at the refinery, had come to the trailer office that day to deliver a pair of forgotten glasses to her husband, James. Both she and James were killed in the explosion.

Ground-level view of the debris field and twisted and charred piping in the aftermath of the March 2005 explosion at BP’s Texas City, Texas oil refinery.

BP had become the owner of the Texas City oil refinery, in the late 1990s when it acquired the facility from the Amoco Oil Company. The refinery, located on the outskirts of Galveston, about 35 miles southeast of Houston, extends for nearly two square miles. At the time of the explosion it was the third largest oil refinery in the U.S. When the blast occurred that day, the surrounding community was rocked; 43,000 people were told to “shelter in place,” emergency parlance for “stay in doors and pray that nothing worse happens.” Homes were damaged as far away as three-quarters of a mile from the refinery. Financial losses would later be totaled at more than $1.5 billion.

Prior to BP’s ownership, the refinery had suffered some years of neglect under Amoco. But the situation did not appear to improve much after BP became the owner in the late 1990s. Three months before the explosion, in January 2005, one report on the refinery by consulting firm Telos had examined conditions at the plant and found numerous safety issues, including “broken alarms, thinned pipe, chunks of concrete falling, bolts dropping 60 feet, and staff being overcome with fumes.” The report’s co-author reportedly stated later, “we have never seen a site where the notion ‘I could die today’ was so real.”

TV’s “60 Minutes” did an investigation of the Texas City disaster, aired on October 29th,2006.

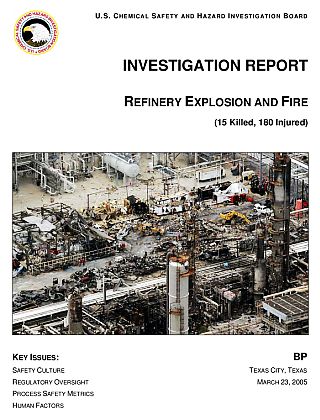

Among the federal agencies investigating was the U.S. Chemical Safety Board (CSB), which sent a team to the site early on. While the CSB’s final investigative report would not come until late 2006, the agency took other actions aimed at BP. On August 17, 2005, the CSB recommended that BP commission an independent panel to investigate the safety culture and management systems throughout its entire BP North America operation. This BP agreed to do, and a panel led by former U.S. Secretary of State James Baker III was convened, but would not report until January 2007 (this “Baker report” is covered later below).

Meanwhile, the CBS-TV newsmagazine, 60 Minutes, spent three months investigating the explosion at Texas City. On its Sunday night edition of October 29th, 2006, the newsmagazine aired its findings with correspondent Ed Bradley’s interviews of company and government officials, workers and family survivors, including Pat Nickerson and Eva Rowe quoted earlier above. “What we found,” explained CBS of the show in an introductory summary, “was a failure by BP to protect the health and safety of its own workers, even though the company made a profit of $19 billion last year.”

Lesley Stahl introduced the “60 Minutes” Texas City story. |

Ed Bradley, CBS correspondent for the Texas City story. |

Carolyn Merritt, head of the U.S. Chemical Safety Board, offered key findings of BP failures at the Texas City refinery during ‘60 Minutes’ broadcast, Oct 29th, 2006. |

As the program aired, Lesley Stahl introduced the segment, but Ed Bradley would be on camera for the interviews he conducted (Bradley, in fact was ill with leukemia at the time but was intent on completing his investigation). “60 Minutes” spent the last three months investigating the explosion at Texas City,” explained Stahl in her introduction. “Ed Bradley found evidence that BP ignored warning after warning that something terrible could happen there.”

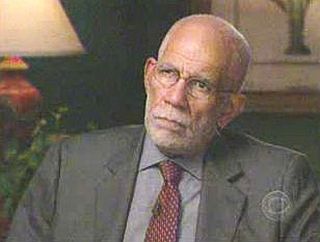

During the 60 Minutes piece, Bradley interviewed Carolyn Merritt, the head of the U.S. Chemical Safety Board, appointed by President George Bush. The 60 Minutes segment ran a few days before the CSB would hold a press conference on what they were finding in their investigation. So when Bradley interviewed Merritt, the CSB was well along in its investigation, and Merritt shared some of what they were finding – which was quite damning of BP. One of the issues was BP budget cuts, and if these had put the Texas City plant and its workers at risk – a question covered in one exchange during the broadcast:

Bradley: …[W]hen BP acquired the Texas City refinery from Amoco eight years ago, the plant already was in a state of disrepair. Instead of spending money to update the plant, BP executives in London told their refinery managers to cut their budgets.

Merritt: Twenty-five percent of their fixed costs were cut. And when you cut that much out of a budget in a facility, you lose people, you lose equipment, you lose maintenance, you lose trainers. Our investigation has shown that this was a drastic mistake.

Bradley: So, as the Texas refinery got older, and needed more maintenance, more attention to safety, BP cut the budget in those areas?

Merritt: Yes.

Bradley: Is there a direct relationship between the budget cut and the disaster at Texas City?

Merritt: We believe there is.

Cover of U.S. Chemical Safety Board’s final report on the BP Texas City, TX refinery explosion, March 2007.

“There were three pieces of key instrumentation that were actually supposed to be repaired that were not repaired and the management knew this,” Merritt said. But BP management authorized the operation on the very units with the faulty instrumentation, knowing the three pieces of equipment were not working properly.

A few days following the 60 Minutes broadcast, at an October 31st, 2006 press conference on the CSB investigation, Merritt singled out the history of unwise management decisions at the refinery: “Cost-cutting and failure to invest in the 1990s by Amoco and then BP left the Texas City refinery vulnerable to a catastrophe. BP targeted budget cuts of 25 percent in 1999 and another 25 percent in 2005, even though much of the refinery’s infrastructure and process equipment were in disrepair.” Operator training and staffing had also been downsized at the refinery. “What BP experienced,”“Cost-cutting and failure to invest in the 1990s by Amoco and then BP left the Texas City refinery vulnerable to a catastro-phe…”

– U.S. Chemical Safety Board Merritt said, continuing her statement, “was the perfect storm where aging infrastructure, overzealous cost cutting, inadequate design, and risk blindness occurred. The result was the worst workplace catastrophe in more than a decade.” When the final CSB report was issues on March 2007 it also noted:

“The Texas City disaster was caused by organizational and safety deficiencies at all levels of the BP Corporation. Warning signs of a possible disaster were present for several years, but company officials did not intervene effectively to prevent it. The extent of the serious safety culture deficiencies was further revealed when the refinery experienced two additional serious incidents just a few months after the March 2005 disaster. In one, a pipe failure caused a reported $30 million in damage; the other resulted in a $2 million property loss. In each incident, community shelter-in-place orders were issued.”

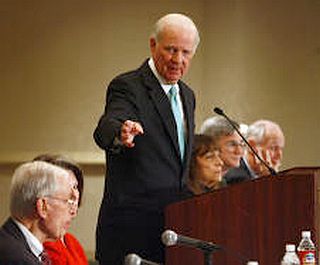

Former U.S. Secretary of State, James Baker, delivering his panel’s findings on BP’s U.S. operations, Houston, Texas, 2007. |

Cover of the Baker Report: “The Report of The BP U.S. Refineries Independent Safety Review Panel,” January 2007. |

The Baker Report

As recommended by the CSB, a special panel was commissioned by BP and headed up by former Secretary of State James Baker to conduct a third-party review of BP corporate practices leading up to the Texas City explosion, including a review the company’s practices at five other U.S. BP refineries. The “Baker Report,” as it was called, released in January 2007, did not find much to commend in BP’s operations. Among other things, Baker’s group found that inspections on volatile process units at BP refineries often were long overdue. In other cases, near catastrophes went uninvestigated, and known equipment problems such as thinning pipes and vessels went unrepaired for up to ten years.

In a follow-up video news conference to the Baker Report with BP’s then CEO, John Browne, the CEO stated: “If I had to say one thing which I hope you will all hear today it is this: BP gets it. And I get it too…,” suggesting that the company would change its ways. But apparently, BP didn’t “get it,” as in the years following the Texas City disaster, the company continued to have spills, leaks and other incidents at its U.S. operations and those abroad, making BP one of the classic corporate recidivists (see sidebar below).

In fact, several years after the 2005 disaster, in September 2009, BP was fined $87.4 million by OSHA for unaddressed worker safety violations at the very same Texas City oil refinery where the explosion had occurred.

The fine was for failing to implement workplace safety improvements under a settlement made with OSHA following the 2005 Texas City refinery explosion. In a six-month investigation, OSHA found 270 uncorrected workplace safety violations and 439 new workplace safety violations at the refinery. OSHA noted that four more workers had died at the Texas City refinery since the 2005 explosion.

Jordan Barab, then acting assistant secretary of labor for OSHA, said the agency had found “some serious systemic safety problems within the corporation” and at the Texas refinery. “The fact that there are so many still outstanding life-threatening problems at this plant,” said Barab, “indicates that they still have a systemic safety problem in this refinery.” And as would be revealed by subsequent events in the Gulf of Mexico in 2010, BP apparently had yet to address its systemic problems found elsewhere in the corporation.

|

“BP’s Other Messes” Texas City wasn’t the only place where BP had problems, and in subsequent years other incidents would occur – in pipelines, with other refining operations, controlling emissions, and with offshore operations. Here are a few of those reported in the 2006-2010 period:  Associated Press map shows the general location of a BP oil pipeline that leaked on Alaska’s North Slope in 2006. April 2006. BP was fined $2.4 million by OSHA for worker safety violations at the company’s Oregon, Ohio oil refinery – workplace safety violations, in fact, that were similar to those that contributed to the Texas City explosion. “It is extremely disappointing that BP Products failed to learn from the lessons of Texas City to assure their workers’ safety and health,” said Edwin Foulke, Jr., OSHA assistant secretary at the time of the fine, also citing BP as among those companies “who, despite our enforcement and outreach efforts, ignore their obligations under the law and continually place their employees at risk.” June 2007. The Michigan Department of Environmental Quality fined BP $869,150 for leaking underground gasoline storage tanks. The Michigan DEQ reported it was then monitoring over 200 former gasoline stations where BP had reported releases from underground tank systems.  The now-famous photo of BP’s burning Deepwater Horizon offshore oil rig in the Gulf of Mexico that killed 11 workers and gushed oil from a sea-bed well for nearly 3 months. February 2009. BP agreed to pay nearly $180 million in fines to correct eight year-old air pollution violations at its Texas City oil refinery. BP agreed to pay the fine for failing to bring the refinery into compliance with air pollution rules under a 2001 consent decree to correct Clean Air Act violations. March 2010. OSHA cited the BP-Husky oil refinery near Toledo, Ohio for workplace safety violations and proposed fines of more than $3 million. BP then operated and jointly owned the refinery with Canadian-based Husky Energy. April 2010. BP’s Deepwater Horizon offshore drilling rig in the Gulf of Mexico exploded on April 20th after a blowout, killing 11 workers and injuring 17 others, as the rig sank two days later. A massive oil spill followed – the largest in U.S. history – threatening the entire Gulf Coast region, its wildlife, marshes and natural resources, and damaging its fishing and tourist-based economies. Millions of people throughout the region were directly and indirectly affected, from lost jobs to shuttered businesses and reduced local revenue. In November 2012, BP and the U.S. Department of Justice settled federal criminal charges with BP pleading guilty to 11 counts of manslaughter, two misdemeanors, and a felony count of lying to Congress. As of February 2013, criminal and civil settlements and payments to a trust fund had cost the company $42.2 billion. In September 2014, a U.S. District Court judge ruled that BP was primarily responsible for the oil spill because of its gross negligence and reckless conduct. In July 2015, BP agreed to pay $18.7 billion in fines, the largest corporate settlement in U.S. history. (See “Deepwater Horizon: Film & Spill: 2010-2016,” for separate story). |

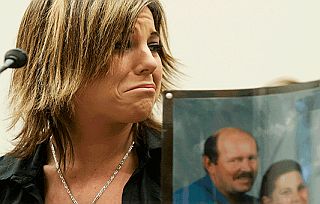

Eva Rowe on the October 2006 “60 Minutes” broadcast.

Eva Rowe’s Fight

Eva Rowe, the 20 year-old who lost both her parents in the Texas City explosion, cited at the top of this story, decided to take BP to court rather than accept a company settlement over the death of her parents.

The day of the explosion, Eva had gone through a harrowing experience, traveling that day from Hornbeck, Louisiana to what she thought was going to be a pleasant visit with her parents. But her life would never be the same again. After her frantic efforts trying to locate her parents following the explosion – calling the plant, hospitals, relatives, and visiting a neighboring worker – she was told unofficially at 4 am that her parents were presumed to be among those killed. Early the next day, televised BP information advised those with missing loved ones to go the Charles T. Doyle Convention Center in Texas City. There, next of kin were escorted to the coroner’ s office to view the deceased. But Eva Rowe was too upset to view her parents’ remains and instead began filling out paper work on her parents’ physical descriptions and medical records. By the end of the day, her parents had been identified through dental records and DNA. “That was the end of my life as I knew it,” Rowe would later say, describing her emptiness and hurt on losing her mother and her father.

Eva Rowe, holding a portrait photograph of her parents, James (44) and Linda (43) Rowe, killed in the BP explosion.

Eva too, had once worked briefly for a few months with her dad at another oil refinery in Corpus Christi, where he was a civil superintendent at the plant, overseeing general construction activities. He found Eva a job as a pipe fitter’s helper, but only for a brief time. Still, that experience was enough to have given Eva some idea of what a refinery environment was like. Eva had not had work after high school, and was living with her boyfriend back in Hornbeck. But she was still close to her mother, whom she would call her best friend. It was in October 2004 that Eva’s mother decided to join her husband, then working with Merit at the Texas City BP refinery. Linda soon had a job there working in the toolroom. And it was in the temporary office trailer at the Texas City refinery that was blown apart March 23rd, 2005 where both Linda and James Rowe were killed.

BP’s then CEO, Lord John Browne, visited Texas City the day after the explosion, stating the company would be assisting the injured and those who lost loved ones.

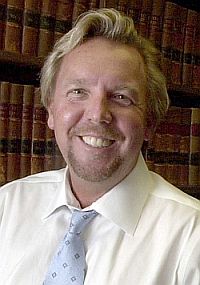

Brent Coon, attorney, Beaumont, TX.

As Mimi Swartz, writing in Texas Monthly would observe: “Of all the death cases [in the BP Texas City disaster], Coon felt that Eva’s was the most compelling, because she had ‘driven into the chaos’ and because she had lost both parents. He also felt strongly that winning money would not be enough—for Eva, for him, or for that matter, for the United Steelworkers. … Coon understood the value of a public spectacle. He wanted to make an example of BP, and to do so would require a motivated plaintiff.”

By late June 2005, within a few months of the explosion, a number of families who had lost loved ones in the Texas City explosion settled with BP, some for amounts in the millions. “It’s the right price,” attorney Robert Kwok said at the time, then representing a spouse of one of the workers who had been killed. “They are basically erring on the side of generous,” he said of BP.“…They [BP] are offering money that is very hard for claimants and their lawyers to walk away from.”– Robert Kwok, Attorney “They are offering money that is very hard for claimants and their lawyers to walk away from.” Some of the settlements were reportedly “on the high end of tens of millions of dollars apiece.” Attorney Richard Mithoff, then representing several families of workers killed in the BP explosion said, “I think there is a clear recognition on the part of BP that they would be held accountable in a court of law.” And he also expressed some surprise at how quickly BP had settled the cases. “I’ve been involved in a lot of early negotiations but none have settled this early,” he said. Eva Rowe’s brother, Jeremy, would also settle with BP. But if every plaintiff settled and no court action occurred, many internal BP documents on the refinery’s operation and BP decision making would never see the light of day. Such documents would remain under court seal, as confidentiality of company information is customarily the practice in settlement agreements – a quid pro quo some might say. Eva Rowe would determine that she did not want that to occur in her case.

March 2006: Eva Rowe placing wreath at make-shift memorial outside BP’s Texas City plant on the one year anniversary of explosion that killed her parents. AP photo/ Melissa Phillip.

“I might be from the woods, but I’m street-smart,” she would later tell the Texas Monthly’s Mimi Swartz. “They tried to treat me like I was stupid. I wanted the public to know. They couldn’t pay me enough to be quiet.”

It took Eva a full year to view the autopsy photos of her parents given to her earlier by the county coroner. She had been unable to look at them before, with Coon’s office holding them for her. But when she finally did view them she saw “the charred remains of her decapitated mother” (struck by a falling object during the explosion and fire), and “what she believed were streams of tears on her father’s blood-stained face,” according to Texas Monthly. The photos motivated her more than ever to stand her ground with BP.

Brent Coon with his client, Eva Rowe, prepping with some model refinery apparatus.

BP’s legal team, meanwhile, played hard ball during negotiations and depositions, using tactics aimed at intimidating Rowe and any others who might challenge the company in court. In Rowe’s case, she was assured that even if she won in court, there could be large financial consequences. She was told by BP that she would be responsible for their court costs if the jury award was less than the settlement offer.…Eva would see strangers parked in a car near her home. During the day, she was constantly followed… A bodyguard was hired to be with Eva at all times… During her deposition, BP’s attorneys got personal, asking her about drinking and marijuana and cocaine use and an altercation at a gas station that ended with her being led away in handcuffs by the police. Eva pled youthful indiscretion and teenage experimentation. Still, BP’s attorneys had unnerved her, making her feel like she was the one at fault, not BP. However, BP’s lawyers made it clear that should Eva’s case go to trial, the jury would be “entitled to know who Eva Rowe is.” Beyond the deposition and courtroom tactics, there were other more troubling concerns. According to Coon, Eva would see strangers parked in a car near her home. During the day, she was constantly followed as she tried to live and rebuild her life. At the suggestion of Coon, a bodyguard was hired to be with her at all times. BP’s attorney’s, in one statement to the court, claimed the company “did not have people on surveillance.” Still, Rowe was so afraid for her safety on one occasion she called the police.

Brent Coon & Associates dug deep into the BP record preparing their case.

The negotiations and maneuvering over Eva’s case would drag on for months. The September 2006 trial date was also postponed. Eva meanwhile, was still in a state of some personal duress and bereavement, and during this time, roughly between September 2005 and August 2006, she had a string of misadventures and personal problems – troubles with a new boyfriend (“didn’t support my cause”); an auto accident; and some drug incidents (charges later dropped). All of this suggested to Coon, worried about the emotional state of his client, that bringing the case to some final resolution sooner rather than later would be in the best interests of all concerned. Meanwhile, a new trial date had been set for November 2006. Nor had John Browne’s deposition occurred. But by late October, both sides were girding for the jury selection process, as their legal teams had encamped to respective floors of Galveston hotels expecting a long court battle.

Ed Bradley, during the “60 Minutes” Texas City broadcast. |

Eva Rowe during the “60 Minutes” broadcast, Oct 29th, 2006. |

Then on Sunday evening, October 29th, 2006, the 60 Minutes broadcast aired, which had included segments with federal safety officials and others, as discussed earlier above. The broadcast was a searing indictment of BP management’s role in the Texas City disaster. The show had also included on-camera segments with Eva Rowe and Brent Coon. During the end of that broadcast, Ed Bradley had questioned Eva specifically about the BP settlement process:

Bradley: A lot of people who suffered terrible losses that day have already settled with B.P. Has B.P. offered to settle with you?

Rowe: Yes.

Bradley: And they’ve offered you, I assume, a substantial amount of money?

Rowe: I want everyone to know what they did, you know. If we settle and all, everything we know has to remain confidential. I don’t want that to happen.

Bradley: So you’re willing to go to trial?

Rowe: I’m ready. I’m ready to go to trial.

That TV broadcast, beyond being a searing indictment of BP’s management failures at the Texas City refinery, was also a nightmare for the BP legal team trying to prevent Eva Rowe from going to trial. For now, with Eva on camera making her case plain to millions of viewers all across the country, BP’s course of action was made all the more difficult. But following the broadcast, BP sent out thousands of “dear neighbor” letters throughout Texas City claiming it had made substantial safety improvements at the plant, and promising to spend $1 billion more on improvements in the next five years. Coon charged that BP was trying to influence the jury pool in advance of their November trial. Still, Coon kept talking with his BP counterpart, William Noble, the company’s chief litigator on the case. About two weeks before jurors were to be selected, the two sides appeared to be making some progress in their talks. Coon kept pushing for agreement on the public release of documents. Then on the morning of November 9th, 2006, when jury selection was about to begin, BP decided to settle and meet Eva Rowe’s terms.

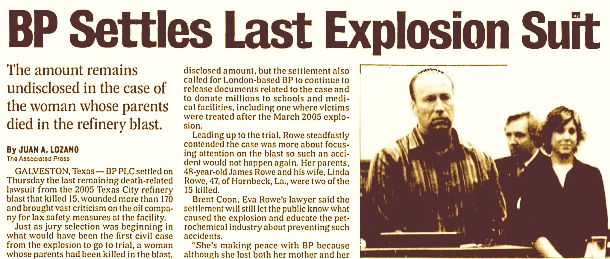

Headlines of BP’s legal settlement with Eva Rowe in the final lawsuit in the Texas City, TX refinery explosion. Associated Press story appearing in various newspapers, here in ‘The Lakeland Ledger,’ Lakeland, FL, November 10th, 2006.

BP agreed to release the documents Rowe and Coon wanted to be made public. In the end, nearly seven million pages of internal BP documents would be published, much of which is available through a public website. And in addition to a payment to Eva, BP also paid out millions to a group of schools and universities, hospitals and charities nominated by Rowe, including: $12.5 million to the Blocker Burn Unit at Galveston’s University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB); $12.5 million for the Mary Kay O’Connor Process Safety Center at Texas A&M; $5 million to the College of the Mainland, in Texas City, for a safety program; $1 million to St. Jude’s Children’s Research Hospital (James and Linda Rowe’s favorite charity); and $1 million to Hornbeck High, where Eva’s mom had been a teacher’s aide. BP also created a fund for victims of the explosion and pledged to match donations up to $6 million. In the end the total BP payout in the Rowe settlement – not counting Eva’s share – would come to $44 million.

March 2007: Eva Rowe, with portrait of her deceased parents, offering testimony at Congressional hearing on the BP Texas City disaster. Brent Coon is seated behind her at right. |

March 2007: Eva Rowe, at the same Congressional hearing noted above, turning emotional listening to testimony. |

When reporters asked Rowe in a news conference if she could ever forgive BP for what happened to her parents, she replied: “I’ll probably never say BP is a good company. They killed my parents to save money.”

Eva Rowe thereafter became an advocate for worker safety issues, having designated a portion of the settlement money to oil refinery workplace safety research and education.

She was also called to offer testimony in Washington, D.C. in March 2007 for a Congressional hearing on the Texas City explosion. She testified at that hearing – before the House Education and Labor Committee, and was also at the witness table for questions during that hearing along with Frank Bowman, a member of the Baker Report panel; Carolyn Merritt of the U.S. Chemical Safety Board; and Red Cavaney of the American Petroleum Institute – all of whom gave testimony that day as well.

Brent Coon’s law practice – thriving in 2007 when he had some 150 lawsuits pending against BP in the Texas City litigation – went on to even greater heights as he became noted for his role in the Eva Rowe case and others. By mid-2010, following BP’s Gulf of Mexico offshore blow-out, Brent Coon & Associates picked up additional business working with those suffering losses in that disaster. His firm now has some 20 offices around the country with 60 litigators representing clients on worker safety, environmental, public health, and personal injury cases.

As for BP Texas City, the company began the process of selling that refinery in 2011, as it needed capital to cover the costs and liabilities of its Deepwater Horizon disaster mentioned in the “other messes” sidebar above. In early 2013, BP completed the sale of the refinery to Marathon Petroleum Corporation for $2.5 billion.

|

“The Daily Damage” This story is one of an occasional series at this website that will feature the ongoing environmental and societal impacts of industrial spills, fires and explosions; toxic chemical releases and waste issues; air and water pollution; and other “daily damage”. These stories will cover both recent incidents and those from history that have left a mark either nationally or locally; have generated controversy in some way; have brought about governmental inquiries or political activity; and generally have taken a toll on the environment, workers, and/or public health and safety. My purpose for including such stories at this website is simply to drive home the continuing and chronic nature of these occurrences through history, and hopefully contribute to public education about them so that improvements in law, regulation, and business practice will be made, yielding industries that are safe and clean. |

In terms of industry-wide safety, however, the record in the industry is still pretty atrocious – this according to an excellent bit of reporting by the Houston Chronicle and Texas Tribune which looked at the industry’s record roughly between March 2005 and March 2015. Among their findings: at least 58 workers died at U.S. refineries in the 2005-2015 period (nearly the same number as the decade before); federal officials recorded nearly 350 fires at U.S. refineries in an eight-year span – about one every week; and that federal regulators lacked hard data to accurately track deaths and monitor safety trends within the industry (see the link above in this paragraph for more detail on their reporting).

At the 10th anniversary of the BP Texas City explosion, in March 2015, Eva Rowe was still troubled. “I thought if I helped people I would get better. I haven’t gotten better,” she told the Galveston County Daily Times. Now in her early 30s, she told the Times she didn’t care about the multi-millions she had received in her settlement. “I would rather live on welfare in a trailer in the woods in Louisiana with my parents than live in a mansion,” she said.

See also at this website, for example: “Burning Philadelphia,” a story about the 1975 Gulf Oil Co. refinery fire in that city; “Burn On, Big River,” about the historic pollution of the Cuyahoga River in Ohio; and, “Santa Barbara Oil Spill” about the 1969 Union Oil offshore oil well blow-out and pollution of California’s coastline. Additional environmental stories can be found at the “Environmental History” page. Thanks for visiting – and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research and writing at this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

____________________________________

Date Posted: 28 April 2016

Last Update: 21 July 2019

Comments to: jdoyle@pophistorydig.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Texas City Disaster: BP Refinery, March 2005,”

PopHistoryDig.com, April 28, 2016.

____________________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

Nov 9th, 2006: Eva Rowe and attorney Brent Coon talking with reporters after BP Texas City settlement. |

Dec 2006: Eva Row and Brent Coon at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston, TX, where the Truman G. Blocker Adult Burn Unit was one of the charities designated by Rowe in the BP settlement. |

March 2007: Eva Rowe in Washington, D.C., meeting U.S. Rep. George Miller (D-CA), chairman, House Education & Labor Committee, where Eva delivered testimony. |

April 2016: Full-page BP ad, Washington Post, “Safety Doesn’t Come in a Box,” touting BP’s commitment to safety. |

Reuters, “Deadly Explosion Rocks BP Texas Refinery,” March 23, 2005.

Pam Easton, Associated Press (Texas City, TX), “Explosion at Texas City Oil Refinery Kills 14, Injures More Than 100,” March 24, 2005.

Kevin Moran, “15th Body Pulled from Rubble of BP’s Texas City Refinery,” Houston Chronicle, March 24, 2005.

Associated Press & NBC News, “15th Body Found After Texas Refinery Blast, NBC News.com,(with NBC news video), March 24, 2005.

“The Explosion at Texas City – 60 Minutes,” BP Texas City Explosion Resources Website.

“Texas City Refinery Explosion,” Wikipedia .org.

Ralph Blumenthal, “A Town Used to Danger Shifted Into Crisis Mode,” New York Times, March 25, 2005.

Michael Graczyk, Associated Press (Texas City, TX), “Refinery Explosion: The After- math; Despite Oil Disaster, Locals Say, Texas City A Fine Place To Live,” Herald-Journal (Spartanburg, SC), March 25, 2005, p. A-8.

U.S. Occupational Health and Safety Administration, Press Release, “BP AMOCO Plant Fined $63,000 Following Chemical Release and Fire in Texas City, Texas,” OSHA.gov, August 25, 2004.

Associated Press, “Explosion Third Fatal Accident at BP Refinery,” Lubbock Ava- lanche-Journal, Saturday, March 26, 2005.

Associated Press, “Woman Mourns Parents Killed in Plant Blast,” The Gainesville Sun (Gainesville, FL), March 26, 2005, p. 4-A.

Anjali Cordeiro and Jessica Resnick-Ault, Dow Jones Newswires, “BP: Employees Caused Deadly Blast; Oil Company Says Failures Led to Deaths of 15 People at Texas City, Texas, Refinery in March,” CNN.com, May 18, 2005.

Anne Belli, “BP to Pay Millions to Families in Blast; Settlements of Lawsuits Come as Allegations of Mismanagement Dog the Oil Giant,” Houston Chronicle, June 23, 2005.

“Prudhoe Bay Oil Spill,” Wikipedia.org.

Felicity Barringer, “Large Oil Spill in Alaska Went Undetected for Days,” New York Times, March 15, 2006.

Felicity Barringer, “Oil Spill Raises Concerns on Pipeline Maintenance,” New York Times, March 20, 2006.

Juan A. Lozano, Associated Press, “‘This Could Have Been Prevented; Daughter Grieves for Parents on the Anniversary of Plant Explosion,” The Victoria Advocate (Victoria, TX), March 23, 2006, p. 4-A.

U.S. Occupational Health and Safety Administration, Press Release, “OSHA Fines BP $2.4 Million for Safety and Health Violations,” OSHA.gov, April 25, 2006.

BP Press Release, “BP to Shutdown Prudhoe Bay Oil Field,” August 7, 2006.

“Oil Giant BP Already Under Scrutiny for Allowing Alaska Pipeline to Crumble,” USA Today, August 9, 2006.

Anne Belli, “BP Chiefs Face Depositions in Texas City Blast; Judge Tells BP Leaders to Give Depositions; Two Executives Will Appeal Order in Texas City Case,” Houston Chronicle, August 29, 2006.

“Anger at BP Adds to Daughter’s Grief; After Losing Both Parents, She Says the Oil Giant Ignored Some Safety Problems,” Houston Chronicle, October 20, 2006.

CBS News, Press Release, “Internal BP Documents Examined by ‘60 Minutes’ Confirm Top BP Executives Knew about Safety Issues That Led to a Deadly Refinery Explosion in Texas — Sunday on CBS,” October 26, 2006.

Mike McDaniel, “60 Minutes Confirms BP Knew Texas City Risk; TV Show Confirms Warnings Given BP; 60 Minutes Examines Blast in Texas City,” Houston Chronicle, October 27, 2006

Daniel Schorn, CBS News “The Explosion At Texas City: 2005 Refinery Explosion In Texas Killed 15, Injured 170,” 60 Minutes, October 29, 2006.

U.S. Chemical Safety Board, “BP America Refinery Explosion,” Main Page.

U.S. Chemical Safety Board, News Release and, “Statement of CSB Chairman Carolyn W. Merritt,” October 31, 2006.

Steven Mufson, “Cost-Cutting Led to Blast At BP Plant, Probe Finds,” Washington Post, October 31, 2006.

U.S. Chemical Safety Board, BP Investigation, Animation Video, November 2005, YouTube.com, Uploaded on January 11, 2008. (Run time, 6:14).

U.S. Chemical Safety Board, “Investigation Report: Refinery Explosion and Fire (15 Killed, 180 Injured), BP Texas City, TX, March 23, 2005,” Final Report, March 2007 (PDF file), 341pp.

“Daughter of BP Disaster Victims Settles; Eva Rowe to Get Undisclosed Sum from Oil Giant after Her Parents Died in Texas Oil Plant Fire in March 2005,” CNN.com, November 9, 2006.

Juan Lozano, AP, “BP Settles Last Explosion Suit,” Lakeland Ledger (Lakeland, FL), November 10, 2006, p. E-1.

Anastasia Ustinova, “BP Settlement to Help Future Burn Victims; UtMB Will Use its $12.5 Million Share to Improve Treatment, Study Effects on Tissue,” Houston Chronicle, December 15, 2006.

The BP US Refineries Independent Safety Review Panel [i.e., James Baker Panel ], The Report of the BP US Refineries Independent Safety Review Panel, January 2007.

Caitlin Johnson, “Daughter of BP Victims Fights and Wins,” CBSnews.com, January 9, 2007, (includes CBS Early Show video on the Eva Rowe settlement).

Anne Belli, “BP Flaws Unattended for Years, Report Says; Baker Panel Says Safety Lapses Found at All Five U.S. Refineries,” Houston Chronicle, January 17, 2007.

Steven Mufson, “BP Failed on Safety, Report Says; Baker Panel Finds That Oil Company Skimped on Spending,” Washington Post, Wednesday, January 17, 2007.

Juan A. Lozano, Associated Press, “BP Report Skewers 5 for Texas Blast; the Findings, Released by Court Order, Said Four Officials Failed to Do Their Jobs and Should Be Fired,” Denver Post, May 4, 2007.

Michigan Department of Natural Resources and Environment, “BP Penalized for Failing to Address Leaking Underground Storage Tanks,” Michigan.gov, June 1, 2007.

Mimi Swartz, “Eva vs. Goliath,” Texas Monthly, July 2007 (“Eva Rowe was a wild child from a mobile home in the Louisiana woods until March 23, 2005…”), July 2007.

“Eva’s Story,” BP Texas City Explosion Website.

Jennie Nash, “Rebel With a Cause: A Refinery Explosion Shook Eva Rowe to the Core, So She Brought An Industry to its Knees,” Ladies Home Journal, September 2007.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Press Release, “EPA and B.P. Products North America Resolve Underground Storage Tank Violations at Four Former D.C. Gas Stations,” EPA.gov, October 15, 2007.

BP Statement on Settlements, “BP America Announces Resolution of Texas City, Alaska, Propane Trading Law Enforcement Investigations,” October 25, 2007.

“BP Fined $20 Million for Pipeline Corrosion,” Anchorage Daily News, October 26, 2007.

Brent Coon & Associates, Beaumont, Texas.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, “BP Products to Pay Nearly $180 Million to Settle Clean Air Violations at Texas City Refinery,” February 19, 2009.

Associated Press (Washington, D.C.), “BP Fined Record $87 Million By OSHA,” October 31, 2009.

U.S. Department of Labor, Occupational Safety & Health Administration, OSHA.gov, “Fact Sheet on BP 2009 Monitoring Inspection,” October 29, 2009.

U.S. Occupational Health and Safety Administration, Press Release, “U.S. Labor Department’s OSHA Proposes More than $3 Million in Fines to BP-Husky Refinery Near Toledo, Ohio,” OSHA.gov, March 8, 2010.

Mark Warren, Brent Coon, “The Inside Story of BP’s Negligence on Oil Safety,” Esquire.com, June 28, 2010.

Tom Price, T.J. Aulds, “What Went Wrong: Oil Refinery Disaster; When Fuel Spewed from the Stack of a Gulf Coast Facility in March, It Went Looking for a Spark. It Found One,” Popular Mechanics.

Stanley Reed and Alison Fitzgerald, In Too Deep: BP and the Drilling Race That Took it Down, John Wiley & Sons, December 2010, 256 pp.

Heather Nolan, “Beaumont Attorney Files Claims in BP Oil Spill Lawsuit,” Beaumont Enterprise.com, May 18, 2011.

“Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill,” Wikipedia.org.

Mark Collette, Lise Olsen and Jim Malewitz, “Ten Years After a Texas City Refinery Blast Killed 15 and Rattled a Community, Workers Keep Dying,” HoustonChronicle.com, March 21, 2015.

Mark Collette and Lise Olsen, “For Two Former BP Workers, the Disaster and its Aftermath Remain Vivid,” Houston Chronicle, March 21, 2015.

Lise Olsen, Jim Malewitz, Jolie McCullough and Ben Hasson, “Assembled Data Show How and Where Refinery Workers Continue to Die,” Houston Chronicle, March 22, 2015.

“BP Explosion: 10 Years After” (Special Edition/ 13 Stories), The Daily News (Galveston County, TX), March 2015.

T.J. Aulds, “Eva Rowe: ‘I Thought If I Helped People I Would Get Better. I Haven’t Gotten Better’.” The Daily News (Galveston County, TX), March 22, 2015.

______________________________