Dick Clark at his DJ post in the 1950s. "I don't make culture," he reportedly said at one point, "I sell it."

The son of a radio-station owner in Utica, N.Y., Dick Clark had been a radio disc jockey as a student at Syracuse University. By 1951, when he landed a job at ABC’s WFIL station in Philadelphia, he worked in radio, regarded as too youthful looking to be a credible TV newscaster. Clark’s big break came when the station decided to replace former Bandstand host Bob Horn. A youngish-looking 26 when he took over, Clark quickly made the show his own. He featured musical guests lip-synching their songs and used his teenage audience to “rate” new records. Local audiences loved the show.

American Bandstand, late -1950s-early-1960s.

Clark interviewing singer Bobby Rydell, 1958.

Brokering Rock ‘n Roll

American Bandstand also played another critical role — especially for mainstream culture and the music business. It helped make America more receptive to rock ‘n roll, a music genre not then accepted as it is today. “From the time it hit the national airwaves in 1957,” observes rock historian Hank Bordowitz, “Bandstand changed the perception and dissemination of popular music.” The show helped make rock ‘n roll more acceptable to many adults by bringing the music and the dancing kids into their homes every afternoon, with Clark providing the responsible, clean-cut adult supervision. Clark’s income was soon approaching $500,000 a year.

“We built a horizontal and vertical music situation… We published the songs…, managed the acts, pressed the records, distributed the records, promoted the records… .” – Dick Clark

American Banstand also helped to open the doors to a new kind of music business. And along the way, Dick Clark became a wealthy man, buying into music publishing companies, record labels, and promoting “Philly sound” recording artiststs on those labels — stars such as Frankie Avalon, Bobby Rydell, and Fabian. Clark also became involved in managing the artists, formed a radio offshoot, and conducted live productions. He also made personal appearances as a DJ hosting live dance events called “sock hops” — as many as 14 a week. And he also packaged concert tours, taking the music on the road. He soon had a nice little musical empire in the making. “We built a horizontal and vertical music situation,” explained Clark of his various businesses. “. . . We published the songs domestically and abroad, managed the acts, pressed the records, distributed the records, promoted the records. . . .”

Dick Clark Covers

Annenberg-Owned TV Guide

May 24, 1958 |

“Payola” & Congress

August 1958 cover of 'Teen' magazine with Clark & headline: 'Why America Loves Dick Clark's American Bandstand.'

American Bandstand was broadcast every weekday through the summer of 1963. But in the fall of that year, it became a once-a-week show run on Saturday afternoons. By 1965, Dick Clark, then 35 years old, was making about $1 million a year. By February 1964, American Bandstand moved to Los Angeles, in part to facilitate Clark’s expansion into other TV ventures and film production. It was also easier in L.A. to tap into the recording industry. By 1965, Dick Clark, then 35, was making about $1 million a year. Musically, the sound on Bandstand changed with the times, featuring the California surf sound in the 1960s, and a decade later, the ‘70s disco beat. Through it all, dating from the 1950s when Clark took over, Bandstand was one of the few places on television where ethnically-mixed programming could be seen. In fact, Clark later claimed that he had integrated the show in the 1950s when he became host – a claim later challenged by at least two authors.

1962: Dick Clark interviewing recording artist, Mary Wells, a guest on Bandstand.

Bandstand & Race

Dick Clark did feature black recording artists as guests on American Bandstand – and he did so from his earliest days as host. When Bandstand first went national with ABC in August 1957, Lee Andrews and the Hearts appeared among the first guests performing their song, “Long Lonely Nights.” In that year as well, other black artists also appeared, including Jackie Wilson, Johnny Mathis, Chuck Berry, Mickey & Sylvia, and others. African American artists would continue to appear on the show in fairly regular order over the years.

However, integration of the studio audience at American Bandstand – the audience of dancers seen on TV screens across the country – was quite another matter.

The integration of Bandstand’s studio audience appears to have been very selective and highly controlled at best, with outright discrimination practiced by Bandstand’s gatekeepers. And Dick Clark appears to have sanctioned the practice, or at least allowed it to continue.

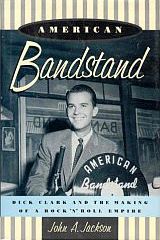

Research by John A. Jackson in his 1997 book, American Bandstand: Dick Clark and the Making of A Rock `n Roll Empire, and more recently by Matthew F. Delmont, in his 2012 book, The Nicest Kids in Town: American Bandstand, Rock ‘n’ Roll, and the Struggle for Civil Rights in 1950s Philadelphia, go into the specifics of why only a very few African Americans ever made it onto the American Bandstand show, especially in the 1957-1964 period. According to Jackson, writing in his book: “[B]y the time American Bandstand appeared in August 1957, featuring the largely black-derived idiom of rock `n roll, the show’s studio audience remained segregated to the extent that viewers around the country did not have an inkling that Philadelphia contained one of the largest black populations in America.”

According to Matthew Delmont, interviewed on the Democracy Now TV program, Dick Clark’s Bandstand had become segregated before Clark took over the show, and before it became nationally televised, when former host, Bob Horn started the show in 1952.

“[T]hey implemented racially discriminatory policies in 1954 and 1955, because they were concerned about fights that were happening outside of the studio,” explained Delmont.

“…Bandstand didn’t want to bring any of that sort of potential teenage violence into the studio and upset advertisers or viewers.”

“So, when Dick Clark took over the program in ’56, it was already segregated. And it remained a segregated program from ’57 until it left for Hollywood in 1964.”

Delmont believes Clark and Bandstand missed an opportunity to have played more of a leadership role advancing civil rights given the show’s national prominence and its tremendous sway over youth culture. See Delmont’s website for details on his book and its findings.

There were a variety of exclusionary methods used by Bandstand that contributed to the practice of keeping black teens off the show. Philadelphia, like other northern cities at the time, was a racially mixed city. And the neighborhood where American Bandstand’s WFIL TV studio was located was also mixed racially. However, the on-screen studio audience of American Bandstand did not reflect that composition. It’s true that for some blacks, the music on Bandstand – especially in the early and mid-1950s – wasn’t their favorite kind of music to begin with, and so there was some self exclusion. But for other blacks who wanted to be on the program, admission was nearly impossible.

1957: Teenagers wait in line for a chance to be admitted to the WFIL studios where ‘American Bandstand’ TV show was broadcast. Researchers have found that discriminatory practices were used to keep African American teens off the show.

Those who stood on line outside the studio hoping for admission, could be eliminated for “dress code” reasons. Tickets to get on the show were handed out on the basis of advance written requests made by the teenagers. However, the station screened those requests, some by area of the city, and others on the basis of the last names submitted on the requests – with Polish, Itallian, and Irish sounding last names receiving preference. Later, “Bandstand memberships” were used, and when maxed out, no new folks could get on the show. Blacks did get on the show, but in very sparse numbers. News accounts about the difficulty of blacks getting on the show were reported, but mostly without effect.

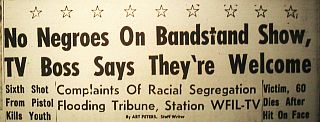

Sept 1956: Philadelphia Tribune headline about the lack of African American teens on the ‘Bandstand’ TV show.

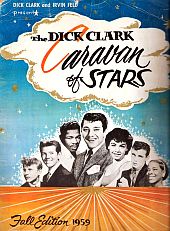

1959: "Caravan of Stars" booklet.

Caravan of Stars

In 1959, initially with the help of a promoter named Irvin Feld, Dick Clark began what would be called the “Caravan of Stars” show – an annual rock ‘n roll road show featuring some of the biggest names in the business, taken to various parts of the country for a series of shows. The Caravan road shows ran for several years, through the early 1960s.

Like Bandstand, the Caravan shows had black and white performers, but ran into overt segregation issues when the show went south. The Caravan performers traveled together and spent many hours in a cramped and uncomfortable bus.

However, there are reports that when Clark took these tours into towns where segregation was still practiced – he insisted on equal treatment of his performers at those venues, otherwise he would threaten to pull the show.

Bruce Morrow, known as DJ “Cousin Brucie” in the 1960s, noted in a later interview at Clark’s death in 2012, that when Clark was confronted with such practice he would say: “ ‘If we don’t go all together, we go out. We will pull the show out’,” explained Morrow. “And he meant it. He put people back on the bus….” A similar account was reported in John Jackson’s book:

…On more than one occasion Clark’s entourage slept on the grass under the stars next to the parked bus after being refused lodging at a hotel. Bookers in many Southern cities were loath to have black acts and white acts perform on the same stage, and when showtime approached , “Dick would look them in the eye and say ‘Listen, we either all go on, or we don’t go on’,” recalled [singer, Lou] Christie.

During the 1964 “Caravan of Stars,” tour member Bertha Barbee-McNeal of The Velvelettes recalled that Clark pulled the whole entourage from a restaurant in the south where they had stopped for food, as Clark was told by the restaurant’s owner they did not serve Negroes. “Then you can’t serve any of us,” Clark told the owner, according to Barbee-McNeal, signaling the group to leave the restaurant and get back on the bus. Of the Caravan shows held in some parts of the south, John Jackson would note in his book: “Although the performers on Clark’s ‘Caravans’ did not conduct sit-ins or demonstrations, simply by having whites and blacks sit together at concerts, they helped pioneer integration in the south.” Jackson also noted that in order to keep racial confrontations to a minimum with his Caravans, “Clark did not tour in parts of the Deep South.”

Dick Clark shown in American Bandstand's 'rate-a-record' segment sometime in the 1970s.

Changing Scene

In the 1970s, with the rise of disco, Bandstand began to become something of an artifact rather than a trend-setter, although still netting its share of popular guests. By the mid-1980s, with the rise of MTV and other music video channels, American Bandstand’s format became dated. In September 1987 Bandstand moved to syndication, and in April 1989 it ran briefly on cable’s USA Network with a new host and Clark as executive producer. The show ended for good on October 7, 1989. Yet over its three decades, American Bandstand played a key role in the music business. Not only did it become the place where major record labels sought to showcase their songs and artists, it also generated millions in record sales each year, plus millions in advertising revenue for ABC. As for recording artists — with the notable exceptions of Elvis Presley, the Beatles, and the Rolling Stones — most of the major rock ‘n roll acts from the 1950s through mid-1980s appeared on the show.

Sonny and Cher made their first TV appearance on American Bandstand, June 12, 1965. The Jackson 5 made their TV debut on the show February 21, 1970, as did Aerosmith in December 1973. In January, 1980, Prince made his TV debut on Bandstand. By the mid-1980s, with the rise of MTV and other music channels, American Bandstand’s style and for-mat became dated.Among others appearing during the show’s 33-year run were: Buddy Holly, Chuck Berry, James Brown, the Beach Boys, the Doors, Stevie Wonder, Smokey Robinson & the Miracles, the Temptations, the

Carpenters, Van Morrison, the Supremes, Marvin Gaye, Neil Diamond, Ike & Tina Turner, Pink Floyd, Creedance Clearwater Revival, George Michael, Rod Stewart, Bon Jovi, Gloria Estefan, Michael Jackson, and last but not least, Madonna, who appeared January 14, 1984 singing the tune “Holiday.” But even after the show’s on-air demise, American Bandstand did not die. In early 1996, MTV’s sister network, VH-1 began broadcasting old Bandstand episodes, mostly from the 1975-1985 period. Within three months, these reruns — called the Best of American Bandstand, with taped introductions by Dick Clark himself — became one of VH1’s top-rated programs.

Dick Clark’s Empire

In addition to American Bandstand, Clark amassed a portfolio of other TV and movie productions, among them, numerous TV specials and awards shows. In the late 1960s he did various television series, talent shows, and also hosted TV game shows, culminating in the late 1970s with The $25,000 Pyramid. In the 1980s and 1990s, his Dick Clark Productions, Inc. turned out more than a dozen made-for-television movies, at least 60 TV specials, several Hollywood films, and radio shows. By 1986, Clark had made the Forbes 400 list of the wealthiest Americans. By 1986, Clark had made the Forbes 400 list of the wealthiest Americans. In recent years he continued his TV productions, landing a prime time TV series, American Dreams. That show was set in 1950s-1960s Philadelphia and used American Bandstand footage in its storyline. It ran for three seasons on NBC during 2002-2005. Clark also parlayed the American Bandstand name into other businesses, using it as a brand and capitalizing on its nostalgia cache. He opened a chain of music-themed restaurants using the name Dick Clark’s American Bandstand Grill. Several of these have opened at airports — Indianapolis, Indiana; Newark, New Jersey; Phoenix, Arizona; and Salt Lake City, Utah. Two others are located in Overland Park, Kansas and Cranbury, New Jersey.

One of Dick Clark's 'American Bandstand' Grills. Similar venues have also opened in airports.

Throughout his career, Clark kept one foot in the world of radio, and would later focus some of his business interests there, also using it as a platform for rock ‘n roll nostalgia.

In 1981, he created The Dick Clark National Music Survey for the Mutual Broadcasting System, which did weekly count downs of the Top 30 contemporary hits. Beginning in 1982, Clark also hosted a weekly weekend radio program distributed by his own syndicator, United Stations Radio Networks. That program focused on oldies, called Dick Clark’s Rock, Roll, and Remember — also the name of a 1976 autobiographical book he wrote with another author. This radio program would also sell recordings of its shows, some of which involved Clark interviews with, and/or features on, current and former music stars. By 1986, he left Mutual Broadcasting to host another show, Countdown America. In the 1990s, Clark hosted U.S. Music Survey, which he continued hosting up until 2004, when he suffered a stroke. Although he recovered partially from his stroke, his public appearances thereafter were limited. On April 18th, 2012, following a medical procedure, Clark died of a heart attack at the age of 82.

Bandstand Acquired

In June 2007, Daniel Snyder, owner of the Washington Redskins professional football team and Six Flags amusement parks, and also a partner with Tom Cruise in a film venture, announced the purchase of Dick Clark Productions for $175 million. In the deal, Snyder became the owner of American Bandstand‘s entire library of televised dance shows stretching over 30-plus years. In addition, Snyder is also acquiring other Dick Clark assets, including the New Year’s Rockin’ Eve broadcast from Times Square, the Golden Globe Awards show, the American Music Awards, the Academy of Country Music Awards, and the Family Television Awards. In 2007, Dan Snyder, owner of the Washington Redskins, acquired Dick Clark Productions for $175 million including Band- stand‘s 30-year library of TV shows. The Dick Clark properties also include the Bloopers television shows and Fox’s popular reality TV show, So You Think You Can Dance. Snyder, who will take over as chairman of Dick Clark Productions, said in a press release, “This was a rare opportunity to acquire a powerhouse portfolio and grow it in new directions.” It was not entirely clear at the time of the deal’s announcement, exactly what Snyder would do with the American Bandstand material, other than mention of possibly using it visually on television screens throughout Six Flags amusement parks while patrons were standing on line. On September 4, 2012, Daniel Snyder’s Red Zone Capital Management reached an agreement to sell Dick Clark Productions to a group partnership headed by Guggenheim Partners, Mandalay Entertainment, and Mosaic Media Investment Partners for approximately $350 million. On December 17, 2015, in response to losses across Guggenheim Partners, the company announced that it would spin out its media properties, including Dick Clark Productions, to a group led by its former president Todd Boehly. In all of these transactions, it’s not exactly clear where the American Bandstand materials are, or what they are being used for.

Cover of Dick Clark's autobiography covering early days of 'Bandstand' and the music industry (with photos, 276 pp). Click for copy.

Additional Bandstand stories at this website include, “Bandstand Performers, 1957;” “Bandstand Performers, 1963;” and “At The Hop, 1957-1958.” See also “Moondog Alan Freed, 1951-1965,” for a somewhat related story about a popular disc jockey, or visit the “Annals of Music” page for additional story choices. Thanks for visiting — and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research and writing at this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle.

________________________________

Date Posted: 25 March 2008

Last Update: 22 November 2020

Comments to: jdoyle@pophistorydig.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “American Bandstand, 1956-2007,”

PopHistoryDig.com, March 25, 2008.

_______________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

Late 1950s: Dick Clark reviewing weekly “top hits” during a segment of the American Bandstand TV show. |

April 1960: Dick Clark testifying at U.S. Congressional hearing on “payola” issue; here before House committee. |

1975: Dick Clark interviewing famous blues guitarist, B.B. King, with what appears to be a birthday cake. |

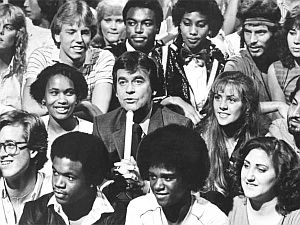

1981: Los Angeles Times photo of Dick Clark seated among show attendees in “Bandstand” bleachers as he introduces a guest act. |

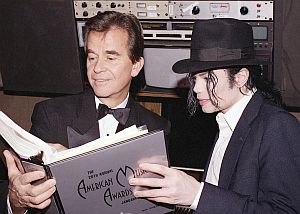

January 1993: Dick Clark with Michael Jackson paging through American Music Awards booklet. |

“Challenging the Giants,” Newsweek, December 23, 1957, p. 70.

“Drive, Talent, Hits, Clark Help Make Philly the Hottest,” Billboard, March 10, 1958, p. 4.

“Dick Clark – New Rage of the Teenagers,” New York Times, March 16, 1958, Section 2, p. 13.

“Tall, That’s All,” Time, Monday, April 14, 1958.

“TV Bandstand: Teenagers’ Favorite,” Look, vol. 22. May 13, 1958, pp. 69-72.

“Newest Music for a New Generation: Rock ‘n’ Roll Rolls On ‘n’ On,” Life, December 22, 1958, pp. 37-43.

“America’s Favorite Bandstander” (Dick Clark cover story), Look, November 24, 1959.

“Facing the Music,” Time, Monday, November 30,1959.

“Teen-Agers’ Dreamboat,” New York Times, March 5, 1960.

Arnold Shaw, The Rockin’ ’50s: The Decade That Transformed the Pop Music Scene, New York: Hawthorn Books, 1974.

Dick Clark and Richard Robinson, Rock, Roll & Remember, Thomas Y. Crowell, Publisher, 1976.

Robert Stephen Spitz, Rock, Roll & Remem-ber, Book Review, New York Times, October 24, 1976.

Michael Shore with Dick Clark, The History of American Bandstand, New York: Ballantine Books, 1985.

“Clark Around the Clock,” Newsweek, August 18, 1986, pp. 26-27.

Summary of the National Register of Historic Places Nomination for American Bandstand building, WFIL and WHYY studios, 4548 Market St., Philadelphia., Pennsylvania, July 28, 1986.

“American Bandstand” and “Dick Clark,” The Museum of American Broadcast Commu-nications.

“Dick Clark,” The Radio Hall of Fame.

“American Bandstand,” Wikipedia.org.

“Dick Clark,” Wikipedia.org.

“Dick Clark Productions,” Wikipedia.org.

Ginia Bellafante, “Ultrasuede Is Funny – VH-1’s Reruns of American Bandstand Prove the Hootie Network Can Outwit MTV,” Time, Monday, April 22, 1996.

John A. Jackson, American Bandstand: Dick Clark and the Making of a Rock ‘n’ Roll Empire, New York: Oxford University Press, 1997.

Fred Goodman, “Roll Over, Beethoven: How Dick Clark Taught American Parents not to be Afraid of Rock-and-Roll and Made a Fortune in the Process,” Dick Clark and the Making of a Rock ‘n’ Roll Empire, Book Review, New York Times, October 26, 1997.

Richard Corliss, “Philly Fifties: Rock ‘n Radio,” Saturday, July 14, 2001.

Hank Bordowitz, Turning Points in Rock and Roll, Citadel Press, 2004.

Thomas Heath and Howard Schneider, “Snyder Adds A TV Icon To His Empire, “Washington Post, Wednesday, June 20, 2007, P. D-1.

Ken Emerson, “The Spin on ‘Bandstand” – Music, TV and Popular Culture Learned to Swing to the Beat of a Different Drummer: Big Bucks,” Los Angeles Times, August 5, 2007.

Becky Krystal, “Dick Clark, Host of ‘American Bandstand,’ Dies at 82,” Washington Post, April 18, 2012.

Matthew F. Delmont, The Nicest Kids in Town: American Bandstand, Rock ‘n’ Roll, and the Struggle for Civil Rights in 1950s Philadelphia, Berkeley: University of California Press, February 2012.

Matthew F. Delmont, “The America of ‘Bandstand’,” Washington Post, Sunday, April 22, 2012, p. B-2.

Democracy Now, “Despite Rep for Integration, TV’s Iconic ‘American Bandstand’ Kept Black Teens Off Its Stage,” YouTube.com, Mar 2, 2012.

Alex Alvarez, “DJ ‘Cousin Brucie’ Recalls Dick Clark’s Commitment To Racial Integration: ‘If We Don’t Go All Together, We Go Out’,” Mediaite.com, April 19th, 2012.

John Liberty, “Dick Clark Remembered: the Velvelettes Say Icon Defended Them in Segregated South, Share Memories of 1964 Tour,” Mlive.com, April 20, 2012.

A documentary film entitled The Wages of Spin, focuses on the history of American Bandstand, the 1950s payola scandal, and Dick Clark. A preview clip from that documentary is available at YouTube and additional information is found at Character Driven Films.