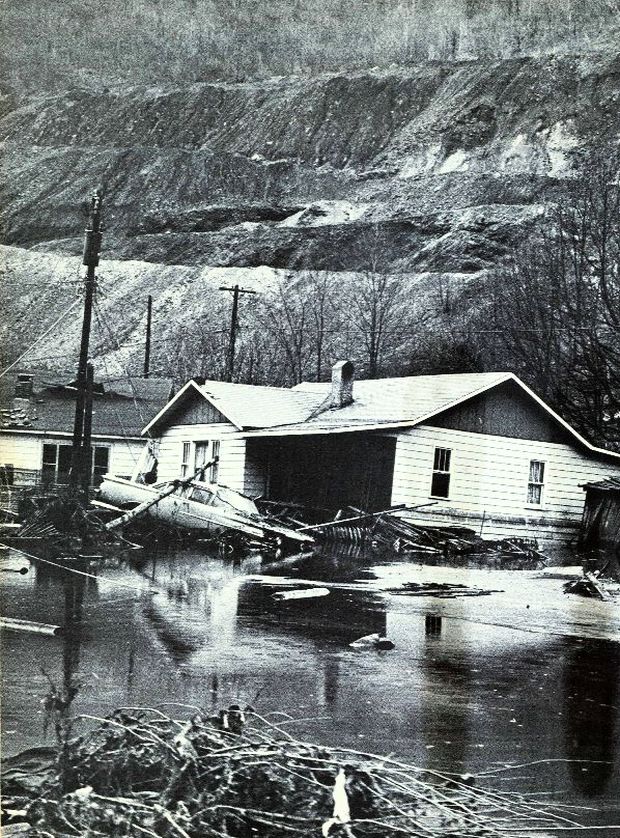

In the early morning hours of Saturday, February 26th, 1972, after three days of rain, a series of coal slurry impoundments in the upper reaches of the Buffalo Creek watershed in Logan County, West Virginia, were beginning to weaken. They were filled to capacity, holding tons of coal wastewater. The dams, built of coal slag wastes, were then owned by the Pittston Coal Company. Coal waste dumping had gone on there for decades, up in the hills, at the headwaters of the Buffalo Creek. But in the valley below, Buffalo Creek ran for about 17 miles where some 5,000 people lived in a string of 16 small towns built along the valley’s bottom lands. When the impoundments up in the hills gave way that February morning, a tsunami-like wall of thick, black coal wastewater went crashing down the hollow, wiping out homes and lives.

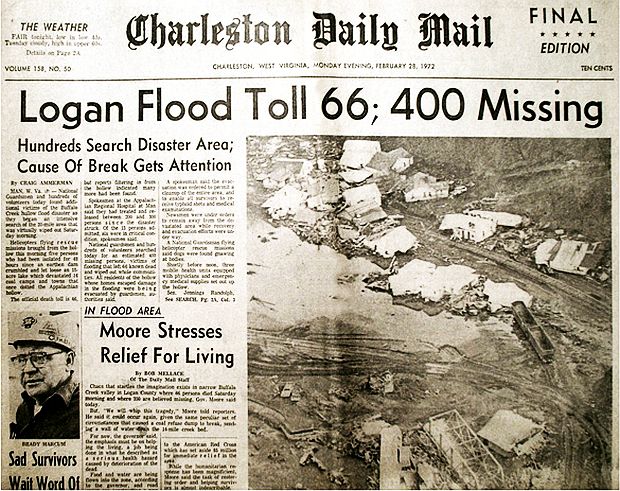

Feb 28, 1972. Headlines of the 'Charleston Daily Mail' of Charleston, WV reporting early death toll of 66 people killed during the Buffalo Creek flood disaster, the result of a giant “coal waste” wall of water from failed “gob” dams high in the hills upstream, also showing houses tossed about in the ravaged watershed. Actual death toll would be 125, nearly twice early reports.

Residents were just awakening that Saturday morning; some entire families were still in bed. In the end, more than 125 people were killed, at least 1,000 injured, and some 4,000 left homeless. The headlines the next day played the catastrophe as a flood disaster, as there had been heavy rain. Yet, as all who lived in those parts knew well, this was a coal disaster, not an “act of God,” as the coal company would later claim.

Some residents in the area, especially those who lived in the town of Saunders, located in the valley directly below the dams, had worried for years about the dams’ strength. They also worried about the mining practice of dumping coal mining “slag” or “gob”– coal mining waste – into the dams. One resident had even written to the governor a few years earlier saying if something wasn’t done about the dams, “we’re all going to be washed away.”“We saw the water lift up our house. When the water set it down again, it just flattened out on the ground. The water was there, and then it was gone…” – Edna Baisden And on the morning of February 26, 1972, just after 8:00 am, that worst fear was realized.

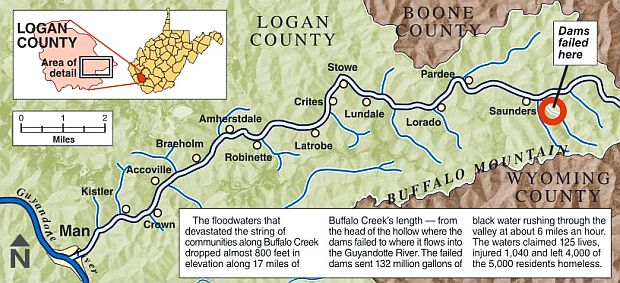

The huge wall of coal wastewater was 30 feet high and 550 feet wide as it gouged its way down the hollow, first smashing through Saunders and then, successively through Pardee, Lorado, Londale, and a dozen other small villages in the narrow creek valley.

The moving wall of wastewater did its damage in seconds, in repeated fashion, as it moved down the hollow. “We saw the water lift up our house,” said Enda Baisden Short, recalling for The Herald Dispatch of Huntington, West Virginia that she and her husband had run from their home early that Saturday morning just prior to coal waste flood. “When the water set it down again, it just flattened out on the ground. The water was there, and then it was gone.”

As the wave moved down the mountain valley it wiped out much of what stood in its path. Some residents in higher hilltop homes overlooking Buffalo Creek, watched as entire houses floated down the hollow, some later crashing into a small bridge downstream. One resident at the scene, later quoted in in Kai T. Erikson’s book, Everything in Its Path, noted of the onrushing tide: “This water, when it came down through here, it acted real funny. It would go this way on this side of the hill and take a house out; take one house out of all the rows, and then go back the other way. It would just go from one hillside to the other…”

Map of Buffalo Creek communities in 1972 shown with disaster summary inset. Sources: “The Herald Dispatch,” newspaper of Huntington, WV, Thomas Marsh, and the West Virginia Division of Culture and History.

The black wall of water was later estimated to have moved at a rate of seven feet per second. In addition to its coal debris, the slurry wave picked up an abrasive and destructive mixture of semi-rotten trees, rocks, and sediment as it went, gouging out the land and becoming a more lethal force capable of battering and sweeping away all in its path. It ripped homes from their foundations, swept up cars, mobile homes, and bridges, and even left twisted rail lines in a few places before it finished its destructive run over 17 miles to the Guyandotte River.

One retired coal miner who survived the flood, but who lost his wife, daughter and granddaughter in the disaster, explained what he experienced in one Charleston Gazette account: “…How I got out of that water, I don’t know… I rode the house a long ways. Then I fell off in the water. I finally caught hold of the railroad with one hand and pulled my myself out. As I rode that house down the creek I could see that the bottom of it was above those telephone poles in the holler.”

February 1972. Aerial photograph from 'The Herald Dispatch' (Huntington, WV) captures some of the enormous damage in the Buffalo Creek valley, showing collection of homes uprooted and floated down the valley, covering roads and rail lines.

Rescue operations and accurate reporting of the dead and missing were made difficult by the fact that access to the area by road had been wiped out, with bridges destroyed and rail lines blocked or flooded. A few helicopters were used initially until local miners and others, and the National Guard, began clearing debris and building makeshift roads and bridges.

Robert Shy, among those in the West Virginia Army National Guard who helped during the crisis, flew helicopters up and down the valley delivering water and milk and picking up dazed and injured survivors. “It just broke your heart to see firsthand the devastation that water could do,” he would tell a Herald Dispatch reporter. “Roads weren’t where they used to be, nor were houses. Railroad rails were twisted, cars were everywhere, bridges were on the roads instead of over the creek.”

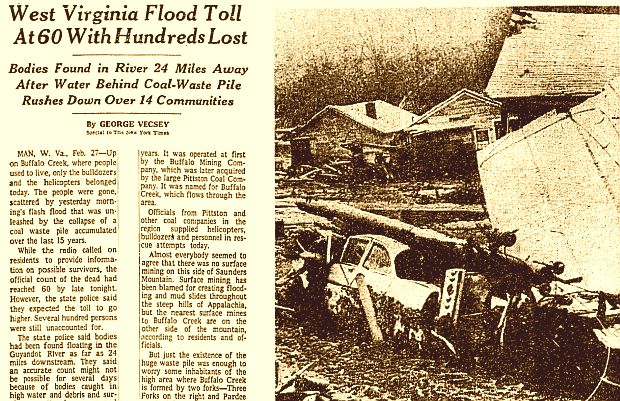

February 28, 1972. An early New York Times story filed from Man, West Virginia, implicated 'coal waste pile' in its reporting on the Buffalo Creek disaster, along with a photo of some of the local damage.

The news of the Buffalo Creek Disaster broke variously across the nation the next few days, in part due to the difficulty of getting to the site. The New York Times ran an Associated Press wire story on the front page of its Sunday, February 27th, 1972 edition, above the fold, bearing the headline, “37 Killed as Flood Sweeps A Valley in West Virginia.” The opening sentence of that story read: “A huge, coal-slag heap serving as a dam burst under the pressure of three days of torrential rains early this morning, sending a wall of water through a narrow valley dotted with small impoverished mining towns.” The Times’ own reporter, George Vecsey, based in Kentucky, managed to reach Man, West Virginia on February 27th, filing his story (above) which appeared in the next day’s edition. UPI photographer Leo Gardner, one of the first outsiders to reach the area reported, “Lorado was wiped out.” Another early report from the devastation noted: “52 bodies lying on both sides of the road running alongside Buffalo Creek.” Some drowned in the floodwaters, while others were buried by landslides, as a thick muck had moved along with the coal water.

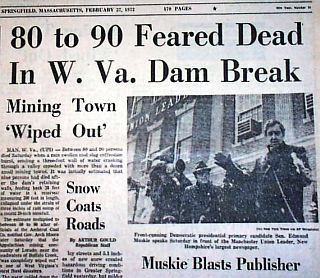

Feb 27, 1972. Headlines from 'The Springfield Republican' of Massachusetts, report on the 'W.Va. Dam Break'. |

The Charleston Gazette of February 1972 reporting on the early flood death total, with front-page photo of damaged homes thrown about on the valley floor. |

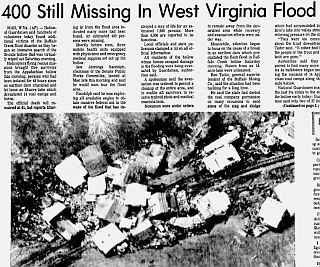

Associated Press wire story reporting "400 missing" in a front-page story that ran in The Tuscaloosa Times newspaper in Alabama. |

Feb 28, 1972, The Logan Banner of Logan, WV reports on the search for victims, relief effort, and first-hand accounts. |

The Springfield Republican newspaper of of Springfield, Massachusetts ran a wire story from United Press International (UPI) on the front page with the headline: “80 to 90 Feared Dead in W. Va. Dam Break; Mining Town ‘Wiped Out’.” That story shared the front page with other national and regional news that day, picturing U.S. Senator Ed Muskie (D-NH) in one photo, then running for the 1972 Democratic presidential nomination, shown campaigning ahead of the New Hampshire primary.

At one point, West Virginia Governor Arch Moore, complaining that the state’s image was getting a bad rap from the media, closed the Buffalo Creek area to reporters. But West Virginia newspapers in the area were covering the tragedy closely, as the grim business of accounting for the dead, injured, and homeless continued. Still, the reported number of dead and missing varied with each day’s news reports, a reflection of the difficulty in finding and identifying bodies in the aftermath.

Later accounts from survivors would describe some of the horrendous moments that families faced as the coal flood tore through the valley.

Roland Staten, a coal miner who had managed to jump off of his house as it was being carried away by the rushing waters, held on to his son as he jumped. But his pregnant wife couldn’t get out; she was trapped in the house. In a court statement later, Mr. Staten recounted his travail and losing his wife: “When I looked back and saw her she said, ‘Take care of my baby.’…That’s the last time I saw her.”

Mr. Staten and his son, meanwhile, swept along in the water, were struggling to save themselves. “I was thrown from side to side and crushed,” he recounted, “my insides was crushed so hard it just seemed my eyeballs was trying to pop out, and… I couldn’t get my breath at all. Somewhere along there I lost that boy of mine. I don’t know where. By that time he had stopped screaming and drunk so much water and everything – I don’t what happened to him.”

Alvid Davis was working outside his home in the community of Stowe when he looked up and saw the flood waters coming, according to an Associated Press report of February 28, 1972. Davis managed to rescue two of his sons, and his neighbors helped pull his 17-year-old daughter from the waters two miles down the hollow. But his youngest son and daughter and his wife were among the missing. “My daughter said she had heard my wife praying when the waters hit the house,” said Davis, later recounting his travail.

Wallace Adkins of Robinette, tried to escape the on-rushing wall of water by loading up his family car. But the water-soaked engine would not start, and as he reached for his wife, the flood “just carried her away.” Adkins did manage to hold onto one daughter and two sons, but his wife and two other children could not be located.

Another survivor and eye witness recounted what he saw to a Logan Banner reporter: “…It was throwing houses around like matchstems and it was picking up cars like they were eggshells…”

Two other witnesses reported to the Logan Banner that they “saw bodies getting hung in trees… The water was black and it was carrying homes and timber…” Another man added: “I just didn’t believe I would see that much water and houses floating down the creek. Men and women, children and animals were …floating in that high wall of water.”

Those who survived saw corpses everywhere. Hundreds of families lost everything — their homes, their belongings, their memorabilia. An accounting of the disaster, and multiple investigations, would then proceed to piece together what had happened there, focused on the coal mining and dam building.

A Pittston Coal Group decal sticker listing some of the company's mining locations in the VA-WV area.

Mining & Dumping

The first coal mining in the Buffalo Creek watershed dated to the 1910s when a few “coal camps” – small mining towns – sprang up following the first rail lines into the area to exploit the coal there. Through the 1940s coal mining and coal washing – including dumping coal refuse and coal wash water – occurred in the area of the Middle Fork, one of three headwater streams that formed Buffalo Creek. By 1957, the Buffalo Mining Company, as part of its strip mining operations, began dumping “gob” — mine waste consisting of mine dust, shale, clay, low-quality coal, and other impurities — into the Middle Fork branch.

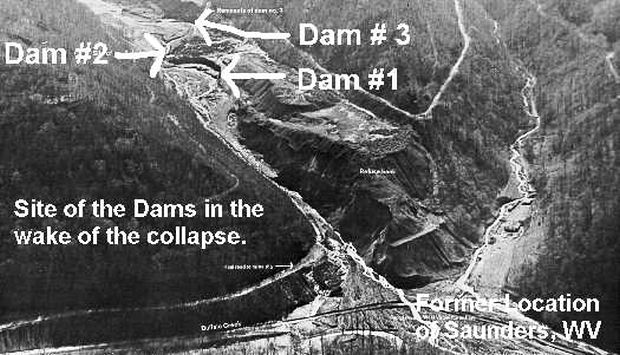

In 1960, Buffalo Mining had constructed its first gob dam, or impoundment, near the mouth of Middle Fork in 1960. Six years later, it added a second dam, 600 feet further upstream. And by 1968, the company was dumping more gob at a third location, another 600 feet upstream. But this dam – dam No. 3 – had been built on top of coal slurry sediment that had collected behind the earlier dams 1 and 2, not on solid bedrock. By 1972, the third dam ranged from 45-to-60 feet in height, and the Middle Fork had become a series of black pools.

The three dams also served as something of a crude pollution-prevention system: filtering, settling out, and retaining the dirty prep plant particles and toxins found in the coal wastewater, also enabling some reuse of the water in processing. Downstream, the coal wastewater — theoretically “filtered” through the dams – would then emerge in a “cleaner” state in Buffalo Creek and beyond. But the dam pools, and the dumping of the solid slag wastes on the dam structures, were both essentially cost-saving, “cheapest-way-to-do-it” coal industry practices. Additionally, on one side of the valley below Dam #1, there was a huge smoldering coal refuse pile.

Aerial photograph used during investigation of Buffalo Creek Disaster, showing the approximate locations of the three coal waste “gop” dams, and the path taken by coal slurry flood wave on its destructive run downstream.

The dams themselves were certainly not state-of-the-art construction. According to one assessment at the time: “These impromptu structures were hardly dams in any technical sense… They were simply piles of coal waste, clay, shale, red dog, and other by-products of the coal preparation process, dumped off the back of trucks and bulldozed to an even height. Many in the downstream communities were keenly aware of the unstable nature of these impoundments, and expressed their concern to government officials….” In fact, there had already been signs of trouble at the dams, which should have raised alarms and efforts at corrective construction.

In March 1967, a partial collapse at one of the dams caused some flooding in the hollow, alarming residents already concerned about the structures. State officials requested a few minor alterations to the impoundment. And that same year, 1967, the U.S. Department of the Interior had warned state officials that the Buffalo Creek dams – and 29 others throughout West Virginia – were unstable and dangerous.“[I]f you don’t do some-thing, we’re all going to be washed away.”

– Pearl Woodrum letter, Feb 1968 Interior’s study had been prompted by a coal dam failure in Aberfan, Wales in 1966 – a catastrophe that had killed 147 people, including 116 school children.

In February 1968, Saunders resident Mrs. Pearl Woodrum wrote a letter of complaint to then Governor Hulett Smith saying in effect, the dams were unsafe. “[I]f you don’t do something,” she wrote, prophetically, “we’re all going to be washed away.” Her letter did bring a state inspector to visit the dams. He reported there was no danger of a washout of Dam No. 1. However, he did question the ability of the overflow pipes in Dam No. 2 to handle excessive runoff. A search of Public Service Commission records in response to Pearl Woodrum’s complaint failed to produce any proof that dams No.1 and No. 2 had ever been formally approved by the state. In March 1968, DNR notified the Logan County Prosecuting Attorney of Pearl Woodrum’s letter, but no action was taken at the local level or by the state.

By June 1970, Pittston had acquired the Buffalo Mining Company. But before the acquisition, Pittston engineers had reportedly surveyed the Buffalo Mining property, and according to company officials who later testified: “Our reports had no indication that there was any danger, or that anything was wrong with the impoundments . . .”In 1971, Pittston was cited for over 5,000 safety violations at its mines nationally. At the time of Pittston’s acquisition of Buffalo Mining, Dam No. 3 was under construction and about 50 percent completed.

Less than a year later, in February 1971, Dam No. 3 failed. However, in this case, Dam No. 2 held and halted the water. The state then cited Pittston for violations but failed to follow up with inspections. Pittston by then had developed a reputation for poor safety practices, and was ranked second nationally in the number of fatal and non-fatal mine accidents. In fact, the company was cited for over 5,000 safety violations at its mines nationally in 1971. But the company challenged each of the violations and paid only $275 of the $1.3 million in fines originally proposed.

Pittston was also the fifth largest corporate landowner in the Appalachian region at the time, holding nearly 375,000 acres. It also held coal reserves of 1.5 billion tons, mostly high-grade metallurgical coal used in steel-making. Beyond coal, and headquartered in New York City, Pittston had other diverse holdings – an oil company, a large trucking firm, the Brink’s armored car company, and forty percent of the warehouses in New York City.

February 1972. Some of the flood damage in the aftermath of the Buffalo Creek disaster in West Virginia, showing "mud line" on damaged home, indicating approximation of flood levels for some structures, while others were carried away in the wave or disintegrated into pieces.

As of February 1st, 1972, dam No. 3 was being filled at a rate of about 1,000 tons of refuse a day, carried from the coal preparation plant to the dam in 30-ton trucks. The company was operating eight mines in the vicinity and ran all the coal through the preparation plant above the dams. The plant was pumping about 500 tons of water-saturated waste into the pond behind dam No. 3 every day. A few weeks later, on February 22nd, a federal mine inspector and the company safety engineer observed the dams and found conditions satisfactory. Three days later, on February 25, with heavy rain, the water behind dam No. 3 was rising one or two inches per hour. The next day, February 26th, at 1:30 a.m. the water was twelve inches from the dam’s crest and oozing through the dam’s surface. Not long thereafter, the dam gave way, creating the horror that unfolded for the Buffalo Creek communities downstream.

Surveying The Damage

As the skies cleared on Sunday, February 27, West Virginia’s Governor, Arch Moore toured the area by helicopter, describing the “awesome destruction” he viewed from above. President Richard Nixon, then in China, had contacted Moore by phone to promise Federal disaster aid. Army personnel, the Red Cross, state and county officials were all on the scene by then as well, trying to feed, clothe and comfort survivors. A temporary morgue was set up at an elementary school in the town of Man.

A helicopter hovers over one location in the Buffalo Creek valley, surveying the damage in the aftermath of the coal dam failures and devastating flood of February 26, 1972. Note mud lines on the building at left, marking flood level.

U.S. Congressman Ken Hechler (D-WV)), who also came to the area on Sunday, February 27th, told reporters that the U.S. Bureau of Mines and state agencies had “failed to demonstrate sufficient concern for the protection of the safety of the people who work in the mines and live in the mining communities.” Hechler also pointed to what he believed was a contributing cause of the flooding: “As I looked through Buffalo Creek valley yesterday, it struck me again that the entire valley is honeycombed with strip mines and the waste from deep mines so that the soil can no longer hold the [rain] water.” Hechler also slammed the coal industry’s power in the area, saying, “the people are prisoners of the coal industry…” And with some irony, he added, “the only building left intact in one Buffalo community was the company store.”

Crowd of onlookers in the distance surveys the enormous debris field jammed up against a downstream bridge following the Buffalo Creek coal flood. Some survivors reported homes exploding or splintering apart with the wave's impact. Gazette-Mail/L. Pierce.

On Monday, February 28th, U.S. Senator Jennings Randolph (D-WV) visited Man High School, a temporary refugee location for Buffalo Creek survivors. Tempers flared there as one local man tore into Randolph. “I told you this was going to happen,” he said, “I told you.“ He had voted for Randolph, but was frustrated with the political process and how the locals were regarded by most politicians. He believed most local people didn’t tell Randolph and other politicians how they really feel. “You build them up with a bunch of political propaganda…..,” he said, also suggesting that the “coal operator’s money” installed the politicians in Washington, and then, “you don’t care nothing about us.”

February 1972. The Charleston Gazette reporting on the rising death toll of the Buffalo Creek Disaster and Pittston’s PR office calling the disaster an “act of God”.

“Act of God”

Not long after the dams had burst, and the flood waters had raged through the Buffalo Creek communities, Pittston’s New York public relations office, attempting to absolve the company from legal responsibility, issued a news release stating that the flood was “an act of God.” The dam, said the Pittston officials, was simply “incapable of holding the water God poured into it.”

At a protest meeting held in the Buffalo Grade School in Accoville a month after the flood, an older woman stood up and shouted out: “I’ve lived up at the top of the hollow for a long time. And I ain’t never seen God up there driving no bulldozer dumping slate on that dam.” Her remarks won applause from most everyone in the room. Robert Weedall, West Virginia’s climatologist, noted in later remarks that yes, “Act of God is a legal term,” but there were other perhaps more apt legal terms that might apply to what had happened in Buffalo Creek, such as “involuntary manslaughter” or “criminal negligence.” The record, however, would prove that “acts of man” had everything to do with what happened at Buffalo Creek.

WV Governor, Arch Moore.

Investigations

By March 2, Republican Governor Arch Moore announced the formation of an Ad Hoc Commission of Inquiry to investigate the flood. Its nine members, however, were either sympathetic to the coal industry, or government officials whose departments might have been complicit in the dams’ failures. After then-president of the United Mine Workers Union, Arnold Miller and others were rebuffed by Gov. Moore regarding their request that a coal miner be added to the commission, a separate Citizens’ Commission was formed to provide an independent review of the disaster.

“The current members of [the Governor’s] panel are either oriented to coal or apologists for the tragedy, so we are creating our own commission of 19 residents to take testimony from eyewitnesses,” said Pat McClintock at the time. McClintock was a field worker for the Black Lung Association, an organization focused on the debilitating disease common to miners. “We do not see this as a disaster in a vacuum,” he said, “but a series of events of coal dominating the lives of West Virginians.”

Both the Governor’s Commission and the Citizens’ Commission set about their investigations, and each group began holding public hearings and collecting information regarding the disaster. But these weren’t the only investigations; there were also several others, including: one or more Congressional committees, the U.S. Geological Survey, the U.S. Department of the Interior, and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

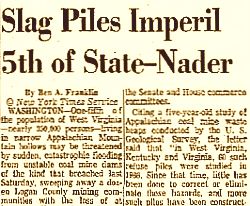

March 5, 1972. Ralph Nader letter to Congressional committees raises dangers of coal dams.

The U.S. Senate Subcommittee on Labor had already begun an investigation, and by late May 1972 also began a series of public hearings on the Buffalo Creek disaster. This subcommittee would hear from dozens of witnesses, and was briefed at one point by experts from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers who provided a scale model of the site with details of what happened (see photo below).

May 1972, Wash., DC. U.S. Senators and experts gather around scale model of Buffalo Creek area in Senate hearing room showing valley below and three coal waste impoundments (#s 8, 5, & 4) that burst causing catastrophic flood on February 26, 1972. Among officials and Senators shown are, from left: Dennis Gibson, Buffalo Mining Co.(22) Garth Fuguay (21, with pointer), Army Corps of Engineers; Sen. Harold Hughes (18); Sen. Jennings Randolph (17); Sen. Jacob Javits (16); Sen. Harrison Williams (15); Sen. Richard Scheiker (19), and Sen. Robert Stafford (20).

Leading off the testimony before the Senate Subcommittee was Garth Fuquay of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (shown in above photo), who had been detailed to the subcommittee to help guide the committee in its investigation. Fuquay would also conduct an early field analysis of what happened there. At the outset of the hearing, Fuquay was the first witness, and the subcommittee chairman, Senator Harrison Williams (D-NJ), submitted for inclusion in the hearing record, Fuquay’s 225-page report, titled “An Engineering Survey of Representative Coal Mine Refuse Piles as Related to the Buffalo Creek, West Virginia, Disaster.” That two-part report, focusing on the failed Buffalo Creek dams and a sampling of other dangerous coal refuse dams in the region, made headlines in a few places on May 30th, 1972, the day the Senate hearings began. One newspaper, reporting on the study and the Senate hearings, used the headlines “Army Corps of Engineers Says Dam Doomed From Start” (below).

May 30, 1972. Headlines from an Associated Press story reporting that the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers -- also testifying at U.S. Senate hearings -- found the the Pittston Coal Co. dam above Buffalo Creek was "doomed from the start."

The Senate subcommittee would later issue some three volumes of material and by June 1972 would call for new legislation to prevent disasters like Buffalo Creek, offering a “Mined Area Protection Bill,” a measure, however, that would not be adopted.

West Virginia Governor's report: "The Buffalo Creek Flood And Disaster".

…Based on the testimony obtained from hearings, technical reports and our own field inspection, the Commission concludes that: Dam No. 3 on the Middle Fork was born out of the age-old practice in the coal fields of disposing of waste material and was constructed without utilizing technology developed for earthen dams and without using or consulting with professional persons qualified to design and build such a structure. The physical conditions leading to the failure of the dam are complex and involve a weak foundation and saturated embankment giving rise to failure of the downstream portion of the dam and a sudden total collapse of the remainder of the dam due to liquefaction. The failure occurred a minute or so before 8:00 a.m. February 26, 1972, and was solely the cause of the Buffalo Creek flood. No evidence of an act of God was found by the Commission.

Norm Williams, Deputy Director, WV-DNR & Citizens' Commission chairman.

The tautly-worded 31-page report offered detailed findings and evidence of corporate negligence and government failures in the disaster, and proposed 21 recommendations. The report found that company and state officials were ill informed of the problems of refuse dams and had not taken timely measures. “Clearly and simply,” said the report, “people living downstream from the Buffalo Mining Company’s coal refuse dam at Saunders were the victims of gross negligence.”

The Citizens’ report also noted that strip mining above the dam had likely contributed to its over-filling. Aerial photos at an Army Corps of Engineers office showed that earlier strip mining of coal seams had occurred on both sides of the slate dump, along with horizontal auger mining boring into the hillsides there. This mining activity, though in the past, had stripped away the water-absorbing forest undergrowth, thus increasing surface run-off during heavy precipitation. The report also noted the possibility that water and coal wastes in abandoned underground mines could break through auger holes and flow into the impoundment behind dam #3, as the practice of disposing coal sludges in abandoned underground mines had occurred in other areas of the state, with sludges breaking through to the surface in some cases.

One of the photos used in “Disaster on Buffalo Creek: A Citizens' Report on Criminal Negligence in a West Virginia Mining Community,” 1972.

The chair of the citizens’ commission, Norman Williams, then deputy director of West Virginia’s Department of Natural Resources, called for the outlawing of strip mining throughout the state. Williams explained that such mining was only viable because the state allowed it to “externalize costs” – i.e., impose its pollution, mine wastes, and environmental damage on landowners and the general public. Williams wasn’t alone in pointing to the ravages of strip mining. In the U.S. Congress at the time, federal legislation was being considered to regulate strip mining, and the Buffalo Creek disaster figured into the debate. West Virginia Congressman Ken Heckler (D) had offered a bill in 1971 to ban all surface coal mining. West Virginia’s Secretary of State at the time, Jay Rockefeller (D) – who became a candidate for Governor running against Arch Moore in the 1972 fall election – also favored banning strip mining. Moore would prevail in the election, campaigning heavily in West Virginia’s coal mining regions, impugning Rockefeller’s position on strip mining. (Rockefeller would later be elected governor and U.S. Senator). The Buffalo Creek disaster, however, did galvanize concern about strip mining and coal safety in Congress, and helped to spur passage of regulatory bills on the House side during Congressional debate in the early 1970s. A final federal strip mine bill, however, would not be signed into law until 1977.

1977 edition of Gerald Stern's book on class-action lawsuit he brought against Pittston Coal Co. on behalf of Buffalo Creek survivors and settled in 1974. Click for copy.

Several lawsuits were also filed in the wake of the Buffalo Creek disaster, including a large class action with 645 survivors and victim family members suing Pittston for $64 million. The plaintiffs settled out of court for $13.5 million in 1974, with each individual receiving an average of $13,000 after legal costs.

The state of West Virginia also sued Pittston for $100 million for disaster and relief damages, but Governor Arch A. Moore settled that case for just $1 million three days before leaving office in 1977. That deal would dog Moore for the rest of his career. Having faced several corruption allegations when serving as governor, Moore left office with this additional blemish on his record. The state later had to pay the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers more than $9 million for recovery work along Buffalo Creek.

Although the Governor’s Commission had referred the case to the Logan County, West Virginia prosecutor for possible legal action against Pittston Coal Company and its subsidiary, nothing came of it. No criminal charges were brought against the mining executives for their negligence in the creation and operation of the illegal and unstable coal waste dams.

The Logan prosecutor said at the time that Pittston’s failure to receive a state dam license was merely a misdemeanor and that a one-year statute of limitations for prosecutions had lapsed. He also concluded that Pittston’s Buffalo Creek Mining Co. could not be charged with negligent homicide because “there was no way to put a corporation in jail.”

In 1973, the West Virginia Legislature passed the Dam Control Act, regulating all dams in the state. However, adequate funding was never appropriated by teh West Virginia legislature to enforce the law. Pittston, meanwhile, would inform its investors that the 1974 settlement that had come with one of the survivors’ lawsuits did not impact the company’s profit margin.

Kai Erikson’s book, “Everything In Its Path: Destruc-tion of Community in The Buffalo Creek Flood”. Click for copy.

In the immediate aftermath of the disaster, various state, local and federal government agencies had initially come together to help plan for the recovery of the Buffalo Creek area. The first restoration, however, came with the railroads, rebuilt to serve the mines, which were operating again within a week of the flood. A few years later, construction began on water and sewage systems, and some permanent housing was built. But $27 million in flood emergency funds was used in 1975 to build a highway that really went nowhere, except to the coal tipples at the head of Buffalo Creek. Four years after the disaster, in 1976, about 100 families were still living in the government provided mobile homes. There had been emergency relief, but little community redevelopment.

The Pittston Coal Co., meanwhile, continued extracting coal in the Buffalo Creek area through its subsidiary there. And it also continued dumping its coal wastes in the area as well, absent the use of watery waste dams. As of 1987, Pittston was still among the ten largest coal companies in the U.S. But following a bitter labor strike in 1989, and the declining profitability of its minerals division throughout the 1990s, Pittston began to wind down its coal operations. In 2002, Alpha Natural Resources purchased what remained of Pttston’s coal business. By 2003, Pittston had moved into one of its more profitable businesses, private security, then adopting its Brinks Company subsidiary as its new corporate name.

The problem of coal waste impoundments in Appalachia — and all across America — has not gone away since the 1972 Buffalo Creek disaster. Nearly 50 years later, there are still hundreds of coal waste dams to worry about, as well as other assorted coal waste dangers throughout the U.S.

In fact, there is a very sizeable “coal waste legacy” that will continue to pose dangers for many rural American communities — and the nation’s rivers and streams — for decades to come, even as the coal industry as a whole winds down its role in the U.S. and global economies. For as it turns out, there are coal waste impoundments, and coal waste disposal methods, of many kinds.

In addition to coal waste dams used in mining and coal washing operations, there are also more than 1,400 coal ash impoundments used mostly at or near coal-fired powerplants in the U.S. In addition, coal wastes have also been dumped into abandoned deep mines and used to “reclaim” strip mines. Still other operations use injection techniques to pump various coal wastes underground. Recent history suggests that a number of these facilities and practices hold public safety risks and/or environmental threats.

In the year 2000, increased attention was focused on the regulation of coal waste impoundments following a failure near Inez, Kentucky. In that case, the bottom of the 72-acre Big Branch slurry impoundment – owned by the Martin County Coal Corp. – broke through an abandoned underground mine located below it. That failure sent 300 million gallons of liquid coal waste tearing through the underground mine chambers, then spewing out of mountainside portals into valley streams below. The toxic coal slurry poured into Kentucky’s Coldwater and Wolf creeks, then to the Tug Fork of the Big Sandy River, traveling more than 70 miles downstream, and eventually reaching the Ohio River, with blackwater visible at Cincinnati. Drinking water systems in ten counties had to be shut down, and a 20-mile stretch of river was declared an aquatic dead zone: more than 1,500 fish were killed. At the time, the EPA called it “the worst environmental disaster in the southeast United States.” The coal company called it “an act of God” (sound familiar?).

In the wake of this disaster, Congress asked the National Research Council to examine ways to reduce the potential for similar accidents in the future, and their report appeared in October 2001, recommending the federal government establish clear authority to review the stability of such impoundments, improve regulation, establish minimum distance rules, and undertake more complete mapping of existing and abandoned underground mines.

December 2008. The failure of a giant 84-acre coal ash impoundment (upper right) at TVA’s Kingston Fossil Plant in Tennessee, released 5.4 million cubic yards of ash slurry into the Emory & Clinch rivers and the downstream community of Harriman, TN.

Then in December 2008 a second major impoundment breach occurred — this time, a failure of a giant 84-acre coal ash impoundment at the Tennessee Valley Authority’s (TVA) Kingston Fossil Plant in eastern Tennessee (photo above). This dam failure released 1.1 billion gallons of coal ash slurry into the Emory and Clinch rivers. More than a dozen homes and hundreds of acres in the down-stream community of Harriman, TN were hit with a gigantic toxic mess. The spill covered the surrounding land with up to six feet of sludge. EPA had initially estimated the spill would take four-to-six weeks to clean up, however, three years later they were still cleaning up.

TVA’s spill was from a “coal ash” impoundment, which is somewhat different than a mine-site slurry impoundment, as it deals with post-combustion, powerplant coal ash, which involves a different regulatory arena than mine-site or coal processing impoundments. Still, the worries for citizens living near either kind of impoundment are equally valid, whether of the mine-site or powerplant variety.

U.S. map showing locations of coal ash waste dams, spills, and contamination compiled by Earth Justice. Click to visit that site.

According to the U.S. EPA, there are over 1,000 operating coal ash waste ponds and landfills, plus many hundreds of “retired” coal ash disposal sites. Some 208 of these “coal combustion” waste sites are known to have contaminated groundwater, wetlands, and/or rivers. A number of leaks and smaller spills have also occurred. EPA has made hazard ratings for hundreds of coal combustion waste ponds and impoundments in the U.S., ranking them for the public safety dangers and environmental risks they would pose in the event of failure. As of December 2014, some 331 of these facilities were rated as either holding a “high” or “significant” safety hazard – meaning likely loss of life in the former case, and significant economic/environmental damage in the latter case. The Earth Justice organization, one of the environmental groups following this issue, has complied a U.S. map of these sites as shown above.

For additional stories at this website on the history of coal and coal mining, see for example, the following: “Paradise: 1971″ (about a John Prine song, strip mining in Muhlenberg County, KY, and the demise of a small town); “Mountain Warrior” (profile of Kentucky author and coal-field activist, Harry Caudill, noted for his famous book, Night Comes to The Cumberlands and his life-long critique of Appalachian strip mining); “Giant Shovel on I-70” (about strip mining in southeastern Ohio during the 1960s and `70s and the use of giant strip-mining shovels there); “Coal & The Kennedys,” (featuring Kennedy family involvement with Appalachian coal communities, deep mine safety, environmental protection, and related political issues, 1960s-2010s); “Sixteen Tons, 1950s” (the famous Tennessee Ernie Ford song and some coal mining history, 1940s-1960s); and, “G.E.’s Hot Coal Ad, 2005” (a General Electric TV ad that features a new breed of coal miner).

Thanks for visiting – and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research and writing at this website. Thank you. — Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

________________________

Date Posted: 31 January 2019

Last Update: 31 January 2019

Comments to: jdoyle@pophistorydig.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Buffalo Creek Disaster: 1972,”

PopHistoryDig.com, January 31, 2019.

________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

Associated Press, “37 Killed as Flood Sweeps A Valley in West Virginia,” New York Times, Sunday, February 27, 1972, p. 1.

“Logan Flood Toll 66; 400 Missing, Hundreds Search Disaster Area; Cause of Break Gets Attention,” Charleston Daily Mail, February 28, 1972.

Earl Lambert, “From The Mountainsides: Many Saw It Happen,” Logan Banner (Logan, WV), February 28, 1972.

Associated Press (Man, WV.), “400 Still Missing in West Virginia Flood,” February 28, 1972.

George Vecsey, “West Virginia Flood Toll At 60 With Hundreds Lost,” New York Times, February 28, 1972.

George Vecsey, “Memories of a Disaster,” GeorgeVecsey.com, February 22, 2012.

George Vecsey, “Homeless Thousands Await Future in Flooded Valley,” New York Times (front page), February 29, 1972.

Ben A. Franklin, New York Times News Service, “Dam Failures ‘Common’: Who’s Liable for Flooding,” Charleston Gazette, February 28, 1972.

“Buffalo Area Declared Health, Safety Hazard,” Logan Banner, March 1, 1972

Mary Walton, “State Warned in 1967 of Larado Dam Danger,” Charleston Gazette, March 1, 1972.

Craig Ammerman, “Eight More Bodies Found; Logan Flood Toll Climbs to 84,” Charleston Gazette, March 3, 1972.

“Hope Wanes for 94 Listed Missing in Logan; Known Flood Dead is 88,” Charleston Gazette, March 4, 1972.

Jules Lob, “Buffalo Creek – Now A Valley of Death,” Charleston Gazette, March 5, 1972.

Ben A. Franklin, “Coal Dam Curbs Urged by Nader,” New York Times, March 5, 1972.

Ben A. Franklin, New York Times News Service, “Slag Piles Imperil 5th of State – Nader,” Charleston Gazette, March 5, 1972.

Jules Loh, Associated Press, “Buffalo Creek Hollow: A Nice Place to Live – Then The Flood,” March 5, 1972.

Jules Loh, Associated Press, “A Lie About God – From Paradise to Hell: The Morning When False Alarms Turned to Reality,” The Sunday Messenger (Athens, OH), front page, March 5, 1972.

George Vecsey, “West Virginians Living in Hollows Fear That Mine Waste Piles in Their Areas Will Cause Next Flood,” New York Times, March 6, 1972.

John G. Morgan, “Angered Citizens Plan Own Logan Flood Probe,” Charleston Gazette, March 7, 1972.

“Media ‘Blow’ Held Worse Than Flood,” Charleston Gazette, March 8, 1972.

Richard Carelli, “Mining Official Blames Explosions on Flood Water Hitting Hot Slag Pile,” Charleston Gazette, March 9, 1972.

“Engineering, Not Rainfall, Given Blame, Logan Banner, March 9, 1972.

“After the Dam Broke, Cries for Control,” Business Week, March 11, 1972.

George Vecsey, “Two Rival Inquiries Are Begun into Flood in West Virginia,” New York Times, March 12, 1972, p. 70.

U. S. Department of Interior, Task Force to Study Coal Waste Hazards, “Preliminary Analysis of the Coal Refuse Dam Failure at Saunders, West Virginia February 26, 1972,” Washington, D.C., March 12, 1972.

“West Virginia: Disaster in the Hollow,” Time, Monday, March 13, 1972.

“Death in Buffalo Hollow,” Newsweek, March 13, 1972.

“Murder in Appalachian,” The Nation, March 20, 1972.

“Engineers Say Buffalo Dam Doomed at Start,” Logan Banner (Logan, WV), May 30, 1972.

Thomas N. Bethell and Davitt McAteer, “The Pittston Mentality: Manslaughter on Buffalo Creek,” Washington Monthly, May 1972.

Mary Walton, “Triangle of Blame Placed in Disaster,” Charleston Gazette, May 30, 1972, p.1.

United States Senate, Committee on Labor and Public Welfare, Subcommittee on Labor, Buffalo Creek (W. Va.) Disaster 1972, Hearings, May 30 and 31, 1972, 2 vols. (plus appendices, vol. 3), Washington: U. S. Government Printing Office, 1972.

Report of the Citizens’ Commission to Investigate the Buffalo Creek Disaster, Disaster on Buffalo Creek: A Citizen’s Report on Criminal Negligence in a West Virginia Mining Community, Charleston, West Virginia, 1972.

The Buffalo Creek Flood and Disaster: Official Report From the Governor’s Ad Hoc Commission of Inquiry, 1973 (as posted at: wvculture.org).

The Buffalo Creek Flood and Disaster: Official Report from the Governor’s Ad Hoc Commission of Inquiry, 1973 (PDF of actual report at Marshall University).

UPI, “Buffalo Creek Flood Inquiry [i.e., special grand jury] Is Off Until After Election,” New York Times, September 13, 1972.

“A Town Stood Here,” Life, October 10, 1972.

William E. Davies, James F. Bailey, and Donovan B. Kelly, West Virginia’s Buffalo Creek Flood: A Study of the Hydrology and Engineering Geology, U.S. Geological Survey, Geological Survey Circular 667, Washington, DC: 1972.

U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Mines (W. A. Wahler & Associates), Analysis of Coal Refuse Dam Failure. Middle Fork Buffalo Creek, Saunders, West Virginia, Volume 1, February 1973.

Ben A. Franklin, “Flood Survivors Sue Mine Concern; Plaintiffs Ask $64-Million — Seek Damages Over ‘Survivor Syndrome’; 800 Pages of Testimony; A Sound Like ‘Thunder’,” New York Times, April 18, 1973.

Tom Nugent, Death at Buffalo Creek: The 1972 West Virginia Flood Disaster, New York: Norton, 1973.

“Survivors of 1972 Dam Disaster Accept $13.5-Million Settlement,” New York Times, July 6, 1974.

Kai T. Erikson, Everything in Its Path: Destruction of Community in the Buffalo Creek Flood, New York: Simon and Schuster, 1976.

“Events Leading To The Buffalo Creek Disaster,” BuffaloCreekFlood.org.

“The Buffalo Creek Disaster – February 26, 1972,” LoganWV.US (website), History and Nostalgia/ Preserving Logan County History.

Tom Price, “Who Killed Buffalo Creek?,” Rolling Stone, January 3, 1974.

Associated Press, “Pittston’s Federal Flood Suit Settled Out of Court,” Bluefield Daily Telegraph (Bluefield, WV), July 6, 1974, p. 1.

Gerald M. Stern, The Buffalo Creek Disaster: The Story of the Survivors’ Unprecedented Lawsuit, New York: Random House, 1976.

J.L. Titchener, F.T. Kapp, “Disaster at Buffalo Creek. Family and Character Change at Buffalo Creek,” American Journal of Psychiatry, March 1976, pp 295-299.

K.T. Erikson, “Disaster at Buffalo Creek. Loss of Communality at Buffalo Creek,” American Journal of Psychiatry, March 1976, pp. 302-305.

C.J. Newman, “Disaster at Buffalo Creek. Children of Disaster: Clinical Observations at Buffalo Creek,” American Journal of Psychiatry, March 1976, pp.306-12.

Paul Cowan, Book Review of Gerald Stern’s “The Buffalo Creek Disaster: The Story of the Survivor’s Unprecedented Lawsuit,” The New York Times Book Review, September 5, 1976, pp.6-7.

Mimi Pickering (Film Director), “Buffalo Creek Flood: An Act of Man” (essay), Library of Congress, 1978 (in 1984, filmmaker Mimi Pickering completed Buffalo Creek Revisited, an update on the flood and its consequences).

Film Clip, “The Buffalo Creek Flood: An Act Of Man,” YouTube.com (8:22), February 20, 2012.

“The Buffalo Creek Flood: An Act Of Man,” Transcript (undated).

“Two Films 1975 and 1984,” Appalshop.org.

“The Buffalo Creek Flood: An Act of Man / Buffalo Creek Revisited,” BuffaloCreekFlood .org, Website.

Dennis Deitz & Carlene Mowery, Buffalo Creek Valley of Death, 1992.

“Buffalo Creek Flood, 1972,” Online Exhibit /Special Collections, Marshall University, 2002.

“Buffalo Creek Special Series,” Charleston Gazette, February 1997.

Ken Ward, Jr., “Agencies Failed to Protect People, Inspector Recalls,” Charleston Gazette, Tuesday, February 25, 1997.

“Modern Marvels: The Buffalo Creek Disaster” (History Channel production), YouTube.com (9:27).

Russell Mokhiber, “Buffalo Creek,” Chapter 5, Corporate Crime & Violence: Big Business Power and the Abuse of the Public Trust, San Francisco: Sierra Club Books, 1998.

“Buffalo Creek Flood,” Wikipedia.org.

Rita Colistra, “The Rumble and The Dark: Regional Newspaper Framing of the Buffalo Creek Mine Disaster of 1972, Journal of Appalachian Studies, Vol. 16, Nos. 1 & 2.

“Buffalo Creek,” West Virginia Division of Culture and History, 2012.

Jamie Goodman/Brian Sewell, “Remembering Buffalo Creek,” The Appalachian Voice, February 21, 2012.

Lori Kersey, “40 Years Ago: Buffalo Creek Disaster,” Charleston Gazette-Mail, February 25, 2012.

Press Release, “New Federal Standards Needed for Storing Coal Waste,” National Research Council (Washington, DC), October 21, 2001.

Betty Dotson-Lewis / Brian Sewell, “The Day Baby Brucie Died: An Oral History of the Buffalo Creek Flood,” The Appalachian Voice, February 27, 2012.

Juliet Eilperin and Steven Mufson, “Many Coal Sludge Impoundments Have Weak Walls, Federal Study Says,” Washington Post, April 24, 2013.

Vicki Smith, “Feds OK Coal Slurry Dam Expansion,” GazetteMail.com, March 25, 2013.

Julie Robinson, “Buffalo Creek ‘Miracle Baby’ Tells Story to Reader’s Digest,” Charleston Gazette, January 26, 2013.

Gallery: The Buffalo Creek Flood, Herald-Dispatch.com, February 26, 2014.

“Death, Destruction, Terror of 1972 Buffalo Creek Disaster Still Vivid,” The Herald-Dispatch, January 15, 2009.

“Coal Waste,” SourceWatch.org.

Coal and Labor Collection, Appalachian Collection, McConnell Library, Radford University, Radford, Virginia.

Erin L. McCoy, “The U.S. Has Nearly 600 Coal Waste Sites. Why They’ve Got West Virginians Worried,” YesMagazine.org, April 23, 2015.

William Rhee, Associate Professor of Law, West Virginia University, “The Buffalo Creek Timeline,” WVU.edu, updated on December 30, 2015.

Emery Jeffreys (former reporter for The Logan Banner; account of his early flood-site reporting), “Mud, Muck and Misery,” LoganWV.us, February 27, 2018.

Brittany Patterson, “The Cautionary Tale of the Largest Coal Ash Waste Site in the U.S.,” AlleghenyFront.org, June 22, 2018.

“The Pittston Company: Company Profile & History,” ReferenceForBusiness.com.

“Pittston Quits the Coal Business,” Buffalo CreekFlood.org.

“Map Feature: Coal Ash Contaminated Sites & Hazard Dams (U.S.),” EarthJustice.org.

“Chronology of a Disaster,” BuffaloCreek Flood.org.

U.S. General Accounting Office, “Delayed Redevelopment was Reasonable after Flood Disaster in West Virginia,” Report of the Comptroller of the United States, Washington, DC: 1976.

First Lieut. Robert C. Withers, “The Disaster of Buffalo Creek,” Report of the West Virginia Adjutant General, Charleston, WV, 1972.

____________________________________