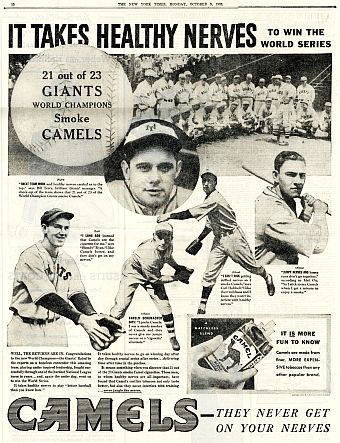

This full-page newspaper ad – with the New York Giants endorsing R.J. Reynolds’ Camel cigarette brand – appeared in the New York Times and other papers in early October 1933.

Indeed, the claims and endorsements made in this ad seem pretty outrageous by today’s standards –stating, for example, that “21 of 23 Giants …smoke Camels.” In other words, an entire sports team – or very nearly that – was used in this ad to endorse the Camel cigarette brand. And this was no ordinary team, but rather, professional baseball’s Word Series champions that year, the victorious New York Giants.

Tobacco advertising in the 1930s was in its heyday – and from the 1920s through the 1950s there was little restriction on the over-the-top claims being made about tobacco’s safety or its human health effects. This ad, in fact, suggested health benefits – i.e., “healthy nerves,” with several endorsing stars making similar statements.

Baseball players and other sports figures had appeared in tobacco ads before, but in the 1930s their appearance in such ads became more common. It was also in the 1930s that tobacco companies began depicting medical doctors in ads, touting the safety of cigarettes. Still, to see an ad like the one shown here, invoking nearly an entire sports team to promote cigarette sales, and making health claims to boot, is pretty striking. Yet this was a much different era, and health-effects knowledge was not what it is today.

Enlarged section from above ad showing pack of Camel cigarettes.

Franklin D. Roosevelt had been elected president in the November 1932 elections, but was not sworn in until March of 1933, then the inaugural custom. Roosevelt faced an unemployment rate of more than 23 percent, thousands of bank failures, and a GNP that had fallen by more than 30 percent. FDR would launch his New Deal in the years that followed, with a flurry of actions and new agencies coming in 1933.

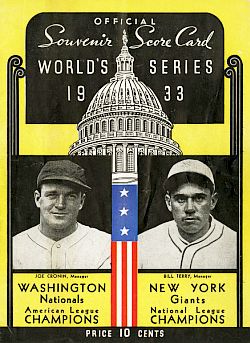

The official program for the 1933 World Series, depicting managers Joe Cronin of Washington, left, and Bill Terry of New York, right.

1933 World Series

The 1933 World Series pitted the National League’s Giants against the American League’s Washington Senators, also known as the Washington Nationals. The Giants had 91 wins and 61 losses in the regular season that year, while the Senators had compiled a 99 – 53 record. The Senators were the surprise victors of the American League that year, breaking a seven-year hold on winning the pennant by either the New York Yankees or the Philadelphia Athletics.

The New York Giants’ venerable and long-standing manager, John McGraw, had retired the previous year, with the Giants’ regular first baseman, Bill Terry, taking on the manager’s job. For the Senators, the equally venerable Walter Johnson, the famous pitcher, had also retired from managing in 1932, as the Senators’ regular shortstop, Joe Cronin, became their manager. Both Cronin and Terry are shown at right on a game program from the 1933 World Series. The World Series games that year were carried on NBC and CBS radio.

Oct 5 1933: Franklin D. Roosevelt prepares to throw ceremonial baseball at Griffith Stadium in Washington, D.C. at Game 3 of the 1933 World Series. Directly right of FDR is Washington manager Joe Cronin and New York manager Bill Terry. AP photo.

Throughout the Series, the Giants’ pitching proved the difference, with Carl Hubbell and Hal Schumacher turning in stellar performances. The Giants took the best–of-seven Series in five games, winning their first championship since 1922.

The final game of the 1933 World Series was played on Saturday, October 7th at Griffith Stadium, with the Giants winning 4-3. Mel Ott hit two home runs that game, the final one coming in the top of the tenth inning, providing the margin for victory. Two days later, the Camel cigarette ad shown above began appearing in newspapers around the country.

The Camel Ad

Enlarged baseball with Camels endorsement from ad above.

Well, the returns are in. Congratulations to the new World Champions—the Giants! Rated by the experts as a hopeless contender, this amazing team, playing under inspired leadership, fought successfully through one of the hardest National League races in years. . .and again the under dog, went on to win the World Series. It takes healthy nerves to play “better baseball than you know how.” It takes healthy nerves to go on winning day after day through crucial series after series. . .delivering time after time in the pinches. It means something when you discover that 21 out of 23 Giants smoke Camel cigarettes. These men, to whom healthy nerves are all-important, have found that Camel’s costlier tobaccos not only taste better, but also they never interfere with training. . .never jangle the nerves.

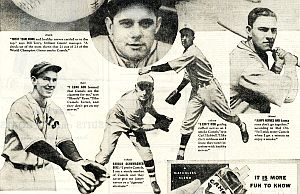

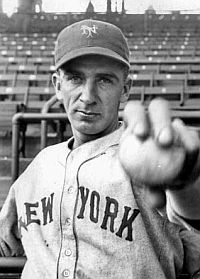

New York Giants’ players featured in the Oct 1933 Camel ad: Bill Terry top, and from left, ‘Blondy’ Ryan, Hal Schumacher, Carl Hubbell & Mel Ott.

Terry is most remembered for being the last National League player to hit .400, a feat he accomplished in 1930, hitting .401. The Giants would retire Terry’s uniform No. 3 in 1984, and it is posted today at AT&T Park in San Francisco. In the Camel ad, Terry, then team manager, is quoted as saying: “Great Team Work and healthy nerves carried us to the top. A check-up of the team shows that 21 out of 23 of the World Champion Giants smoke Camels.”

Carl Hubbell would become one of the game’s great pitchers.

“I long ago learned that Camels are the cigarette for me,” says Ryan in the ad. “I like Camels better, and they don’t get on my nerves.”

Harold “Hal” Schumacher (1910-1993), one of the key Giants’ pitchers through the 1933 season and the World Series, comes next in the Camel ad: “I prefer Camels,” he says. “I am a steady smoker of Camels and they never give me jumpy nerves or a ‘cigarettey’ aftertaste.” Schumacher played with the Giants from 1931 to 1946, compiling a 158-121 win–loss record. He was also a two-time All Star selection.

Carl Hubbell (1903-1988), shown in the photo above right, was a valuable left-handed pitcher for the Giants and a key player in their 1933 World Series championship. Hubbell comes next in the Camel ad. “I can’t risk getting ruffled nerves so I smoke Camels,” he is quoted as saying. “I like their mildness and I know they won’t interfere with healthy nerves.” Hubbell played with the Giants from 1928 to 1943, and remained with the team in various capacities for the rest of his life, even after the Giants moved to San Francisco. Hubbell, a nine-time All Star, was twice voted the National League’s Most Valuable Player. He was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1947. Hubbell is also remembered for his appearance in the 1934 All-Star Game, when he struck out five of the game’s great hitters in succession – Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Jimmie Foxx, Al Simmons and Joe Cronin – setting a longstanding All-Star Game record for consecutive strikeouts. Hubbell was the first NL player to have his number retired, which is also displayed at AT&T Park.

The New York Giants’ Mel Ott, one of baseball’s greatest hitters.

Key Celebrities. Baseball stars such as Mel Ott and Carl Hubbell – and other famous athletes of that era – were among the most publicly-visible and sought-after celebrities of their day. Broadway and Hollywood also had their share of stars, and these celebrities were also sought for product endorsements, including tobacco, and some of those are covered elsewhere at this website. Still, the “celebrity factor” in the 1930s wasn’t quite as intense or ubiquitous as it is today, as there was no television, no internet, no “Dancing With Stars” or “American Idol”– and no 24-7 media machine. In that era, in fact, World Series baseball stars were regarded as top-of-the-line celebrities, considered among the biggest “gets” of their day, prized by marketers. And as admired stars, they were also a key gateway to American youth, who no doubt tried tobacco products because their heroes endorsed them.

Following the 1934 World Series, with the St. Louis Cardinals as champions, a similar Camel advertising pitch was used.

Player Manager Frank Frisch provided the set-up in this ad, also given a by-line as if reporting:

“They sure made it hot for us this year, but the Cardinals came through in great style clear to the end when we needed every ounce of energy to win. We needed it—and we had it. There’s the story in a nutshell. It seems as though the team line up just as well on their smoking habits as they do on the ball field. Here’s our line-up on smoking: 21 out of 23 of the Cardinals prefer Camels.”

2012 book on the history of the cigarette catastrophe. Click for copy. See below Sources for other tobacco books.

R.J. Reynolds, for its part, was then engaged in a fierce advertising battle with American Tobacco for the top spot of the cigarette market, and its move in the 1930s to use baseball players and other athletes endorsing the Camel cigarette brand, helped the company regain its top-of-the-market position.

The public health establishment, meanwhile, has waged a decades long battle against the evils of tobacco, and in recent years some landmark litigation has uncovered documents that the tobacco industry has long known of the addictive and health-damaging effects of tobacco products. Yet the battle with big tobacco is still ongoing.

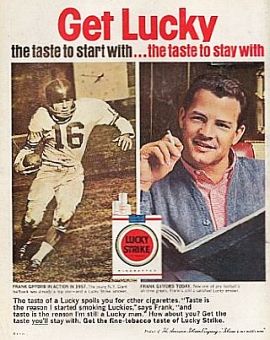

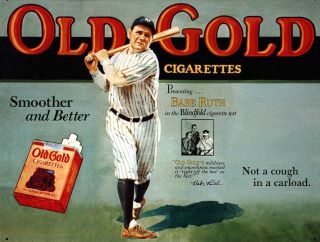

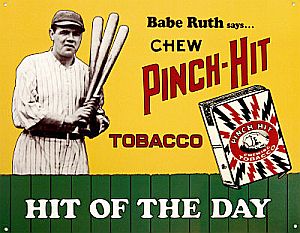

For other stories at this website on athletes and advertising see, for example: “Vines for Camels, 1934-1935” (Ellsworth Vines, tennis star); “Babe Ruth & Tobacco, 1920s-1940s” (Ruth in tobacco ads); “Gifford For Luckies, 1961-1962” (Frank Gifford, football star, in cigarette ad); “Wheaties & Sport, 1930s” (cereal advertising with mostly baseball stars); “Vuitton’s Soccer Stars, June 2010” (celebrity advertising with soccer stars); and, “…Keeps on Ticking, 1950s-1990s” (Timex watch advertising with sports stars). Thanks for visiting — and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research and writing at this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle.

|

Please Support Thank You |

____________________________________

Date Posted: 27 October 2012

Last Update: 4 July 2019

Comments to: jdoyle@pophistorydig.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “21 of 23 Giants…Smoke Camels”

PopHistoryDig.com, October 27, 2012.

____________________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

“It Takes Healthy Nerves to Win the World Series,” October 1933 New York Times advertisement, Stanford.edu, Page visited, October 2012.

“It Takes Healthy Nerves to Win the World Series,” TobaccoDocuments.org, Page visited, October 2012.

Gene Borio, “Tobacco Timeline: The Twentieth Century 1900-1949–The Rise of the Cigarette,” Tobacco.org.

Leah Lawrence, “Cigarettes Were Once ‘Physician’ Tested, Approved; from the 1930s to the 1950s, ‘Doctors’ Once Lit up the Pages of Cigarette Advertisements,” HemOncToday, March 10, 2009.

Tracie White, “Tobacco-Movie Industry Financial Ties Traced to Hollywood’s Early Years in Stanford/UCSF Study,” Stanford.edu, September 24, 2008.

“Not a Cough in a Carload,” Extensive On-Line Exhibit of Tobacco Ads, Lane Medical Library & Knowledge Management Center, Stanford.edu.

Advertisement, “It Takes Healthy Nerves to Win the World Series,” NewspaperArchive.com, Chester Times (Pennsylvania), October 9, 1933, p. 7.

Advertisement, “It Takes Healthy Nerves to Win the World Series,” Plattsburgh Daily Press (New York), October 9, 1933, p. 8.

“Bill Terry,” Wikipedia.org.

“Hal Schumacher,” Wikipedia.org.

“Carl Hubbell,” Wikipedia.org.

“Mel Ott,” Wikipedia.org.

Advertisement, “21 Out Of 23 St. Louis Cardinals Smoke Camels,” San Jose News, October 11, 1934, p. 3.

Advertisement, “21 Out Of 23 St. Louis Cardinals Smoke Camels, by Frank Fritch,” The Miami Daily News, October 11, 1934, p. 10.

Scott Olstad, “A Brief History Of Cigarette Advertising,” Time, Monday, June 15, 2009.

Fred Stein, Mel Ott: The Little Giant of Baseball, McFarland & Co. Inc., 1999, 240 pp.

Fritz A. Buckallew, A Pitcher’s Moment: Carl Hubbell and the Quest for Baseball Immortality, Forty-Sixth Star Press, 2010, 204 pp.

_________________________________