“The Fog of War” documentary film by Errol Morris featuring Robert McNamara. Click for DVD. (see also companion book).

But the Morris film covers much more than the Vietnam period, and in particular, as explored below, a somewhat less well-known chapter of WW II when the American military firebombed more than 60 Japanese cities – all prior to the nuclear bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

The film is framed, in part, around McNamara’s life and times and his long career in government service and the private sector, including his post-WWII work at the Ford Motor Company as one of the “Whiz Kids” who helped turn around the then ailing automaker. McNamara’s involvement in the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962 is also covered.

But the principal subject of Morris’s film is the conduct and carnage of warfare, and the decision making of those who manage it. The film’s title derives from the military concept of the “fog of war,” suggesting difficulty, confusion, and uncertainty in decision making in the midst of conflict.

In addition to winning the 2003 Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature, the film was also selected by the Library of Congress in 2019 for preservation in the National Film Registry as being culturally/historically significant.

Morris also builds his film around some of McNamara’s “lessons,” offered earlier in a 1995 book by McNamara, In Retrospect: The Tragedy and Lessons of Vietnam. During the film, Morris intercuts historic footage and other imagery, audio tapes and voiceovers, as McNamara speaks about his career and experiences in war.

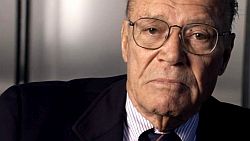

McNamara was 85 years old when Morris interviewed him, and he comes across at times as a somewhat tortured soul on his involvement in WWII and Vietnam; grappling with the morality of decisions made and owning up to his roles in those conflicts. He tries to come to terms with what he has done, personally, while imploring his audience and society in general to consider “the rules of war.” What follows here is that part of the film, and McNamara’s analysis and recollections, that deal with the U.S. firebombing of Japan.

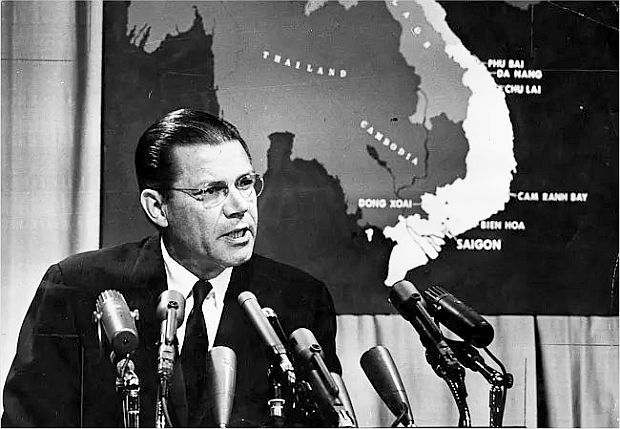

Robert McNamara in a 1960s portrait photo when he was U.S. Secretary of Defense.

World War II

After the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor in December 1941, the U.S. was brought fully into WW II, both in Europe and the Pacific. The Pacific theater, also called the Pacific War, was a vicious and horrific part of WW II — on land, sea, and air. Fighting consisted of some of the largest naval and air battles in history, as well as incredibly fierce battles across the Pacific Islands approaching Japan, all resulting in immense loss of human life. Millions died during the Pacific War – soldiers and civilians – and millions more were injured or made homeless.

Robert McNamara, meanwhile, was a young assistant professor at Harvard in August 1940 where he taught statistical analysis in the Business School. There, he would create the Office of Statistical Control for the Army Air Corps, teaching young Army officers how to increase the efficiency of aerial bombing through applied statistics.

By 1943 he became a captain in U.S. Army Air Forces, serving most of World War II with its Office of Statistical Control. One of his major responsibilities became analysis of U.S. bombers’ efficiency and effectiveness, especially the B-29 forces commanded by Major General Curtis LeMay. By August 1944, U.S. forces had captured Guam, Saipan and Tinian in the Mariana Islands in the Pacific Ocean south of Japan and subsequently built six airfields on the islands to accommodate B-29 bombers. These bases were closer to Japan than previously used bases in China, as B-29s could now make bombing runs to Japan without refueling. Still, the trip to Japan, 1,500 miles away, took seven hours.

McNamara had a front-row seat during the bombing runs, as he was stationed on Guam during those raids, would participate in some debriefings of B-29 bomber pilots after their missions, and provided analysis to General LeMay on bombing efficiency.

In the course of the war, conventional, high-altitude precision bombing of Japanese military and industrial targets was not having the hoped-for success. That’s when a shift was made by General LeMay to bomb Japanese cities – and their civilian populations – as a way to weaken popular support and to destroy home-based war manufacturing.This bombing, however, would not use conventional munitions, but rather, incendiary bombs concocted with the jellied explosive, napalm. One type of firebomb – the M69 incendiary device – became one of the preferred weapons, and was particularly effective at starting uncontrollable fires. These bombs — or more correctly, bomblets — were packaged 36 per carrier cluster bomb. The cluster bombs, in turn, when dropped from B-29s, opened up at about 2,000 feet on their way down, dispersing the 36 bomblets into the air for their fiery handiwork below. Once the M69 bomblets hit the ground, a fuse ignited a charge which first sprayed napalm up to 100 feet from its landing point, and then ignited it.

The B-29s, meanwhile, were also flying in a new way with their firebomb payloads. Normally, with conventional bombing, they flew daytime missions at high altitudes – 20,000 feet and higher – and were out of range of anti-aircraft artillery. But their target efficiency in these runs had fared poorly, as bad weather and jet stream currents were taking their bombs off course. In the firebombing missions, however, LeMay ordered the B-29s to fly at night and fly much lower, at 5,000 feet. LeMay also required the crews to strip away much of their plane’s defensive armaments so they could carry more bombs. The B-29 pilots and crews thought LeMay crazy and they worried for their survival. But while some planes and crew were lost in the five-month long campaign, the new strategy would become highly effective. The fire-bombing B-29s were sent in waves, often with hundreds of planes per target, bombing Japanese cities for hours at a time. In some of the bombings, horrific tornado-like firestorms resulted on the ground, overwhelming firefighting capabilities, superheating the air, and burning, baking, or boiling everything in sight. Some reports tell of people and animals burnt to ash.

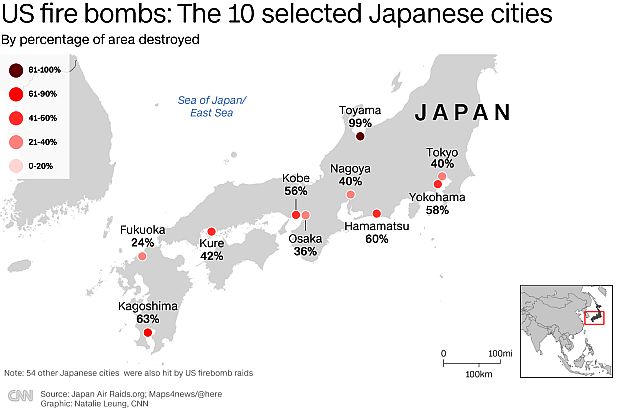

In “The Fog of War” film, one of Robert McNamara’s “lessons” comes about midway in the film – Lesson No.5, that “proportionality should be a guideline in war.” And for this lesson, McNamara draws on the LeMay firebombing campaign, offered in the film clip below. In the clip, McNamara describes the firebombing of Tokyo and other cities, listing the percent of each Japanese city destroyed and naming similar-sized U.S. cities for comparison purposes: Tokyo, roughly the size of New York City, was 51% destroyed; Toyama, the size of Chattanooga, 99% destroyed; Nagoya, the size of Los Angeles, 40% destroyed; Osaka, the size of Chicago, 35% destroyed; Kobe, the size of Baltimore, 55% destroyed, and others. And as he concludes, McNamara emphasizes this was all before the nuclear bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Here’s the clip:

A transcription for the above clip follows below, with Robert McNamara describing the firebombing of Japan:

Robert McNamara: Fifty square miles of Tokyo were burned. Tokyo was a wooden city, and when we dropped these firebombs, it just burned it.

[Appearing on screen]: Lesson #5: Proportionality should be a guideline in war.

Errol Morris: The choice of incendiary bombs, where did that come from?

Robert McNamara: I think the issue is not so much incendiary bombs. I think the issue is: in order to win a war should you kill 100,000 people in one night, by firebombing or any other way? [General Curtis] LeMay’s answer would be clearly “Yes.”

“Killing 50% to 90% of the people of 67 Japanese cities and then bombing them with two nuclear bombs is not proportional, in the minds of some people, to the objectives we were trying to achieve.”

–Robert McNamara

“McNamara, do you mean to say that instead of killing 100,000, burning to death 100,000 Japanese civilians in that one night, we should have burned to death a lesser number or none? And then had our soldiers cross the beaches in Tokyo and been slaughtered in the tens of thousands? Is that what you’re proposing? Is that moral? Is that wise?”

Why was it necessary to drop the nuclear bomb if LeMay was burning up Japan? And he went on from Tokyo to firebomb other cities. 58% of Yokohama. Yokohama is roughly the size of Cleveland. 58% of Cleveland destroyed. Tokyo is roughly the size of New York. 51% percent of New York destroyed. 99% of the equivalent of Chattanooga, which was Toyama. 40% of the equivalent of Los Angeles, which was Nagoya. This was all done before the dropping of the nuclear bomb, which by the way was dropped by LeMay’s command.

Robert McNamara during "The Fog of War" film.

Proportionality should be a guideline in war. Killing 50% to 90% of the people of 67 Japanese cities and then bombing them with two nuclear bombs is not proportional, in the minds of some people, to the objectives we were trying to achieve.

I don’t fault Truman for dropping the nuclear bomb. The U.S.—Japanese War was one of the most brutal wars in all of human history: kamikaze pilots, suicide, unbelievable.

What one can criticize is that the human race prior to that time — and today — has not really grappled with what are, I’ll call it, “the rules of war.” Was there a rule then that said you shouldn’t bomb, shouldn’t kill, shouldn’t burn to death 100,000 civilians in one night?

LeMay said, “If we’d lost the war, we’d all have been prosecuted as war criminals.” And I think he’s right. He, and I’d say I, were behaving as war criminals. LeMay recognized that what he was doing would be thought immoral if his side had lost. But what makes it immoral if you lose and not immoral if you win?

_________________________________

Japanese Cities Firebombed

World War II: March-August 1945

(listed w/ comparable U.S. cities)

Yokahama, Japan / 58% destroyed

U.S. equivalent: Cleveland, OH

Tokyo, Japan / 51% destroyed

U.S. equivalent: New York, NY

Toyama, Japan / 99% destroyed

U.S. equivalent: Chattanooga, TN

Hamamatsu, Japan / 60.3% destroyed.

U.S. equivalent: Hartford, CT

Nagoya, Japan / 40% destroyed.

U.S. equivalent: Los Angeles, CA

Osaka, Japan / 35.1% destroyed.

U.S. equivalent: Chicago, IL

Nishinomiya, Japan / 11.9% destroyed.

U.S. equivalent: Cambridge, MA

Siumonoseki, Japan / 37.6% destroyed.

U.S. equivalent: San Diego, CA

Kure, Japan / 41.9% destroyed.

U.S. equivalent: Toledo, OH

Kobe, Japan / 55.7% destroyed.

U.S. equivalent: Baltimore, MD

Omuta, Japan / 35.8% destroyed.

U.S. equivalent: Miami, FL

Wakayama, Japan / 50% destroyed.

U.S. equivalent: Salt Lake City, UT

Kawasaki, Japan / 36.2% destroyed.

U.S. equivalent: Portland, OR

Okayama, Japan / 68.9% destroyed.

U.S. equivalent: Long Beach, CA

Yawata, Japan / 21.2% destroyed.

U.S. equivalent: San Antonio, TX

Kagoshima, Japan / 63.4% destroyed.

U.S. equivalent: Richmond, VA

Amagasaki, Japan / 18.9% destroyed.

U.S. equivalent: Jacksonville, FL

Sasebo, Japan / 41.4 % destroyed.

U.S. equivalent: Nashville, TN

Moh, Japan / 23.3% destroyed.

U.S. equivalent: Spokane, WA

Miyakonoio, Japan / 26.5% destroyed.

U.S. equivalent: Greensboro, NC

Nobeoka, Japan / 25.2% destroyed.

U.S. equivalent: Augusta, GA

Miyazaki, Japan / 26.1% destroyed.

U.S. equivalent: Davenport, IA

Hbe, Japan / 20.7% destroyed.

U.S. equivalent: Utica, NY

Saga, Japan / 44.2% destroyed.

U.S. equivalent: Waterloo, IA

Imabari, Japan / 63.9% destroyed.

U.S. equivalent: Stockton, CA

Matsuyama, Japan / 64% destroyed.

U.S. equivalent: Duluth, MN

Fukui, Japan / 86% destroyed.

U.S. equivalent: Evansville, IN

Tokushima, Japan / 85.2% destroyed.

U.S. equivalent: Ft. Wayne, IN

Sakai, Japan / 48.2% destroyed.

U.S. equivalent: Forth Worth, TX

Hachioji, Japan / 65 % destroyed.

U.S. equivalent: Galveston, TX

Kumamoto, Japan / 31.2% destroyed.

U.S. equivalent: Grand Rapids, MI

Isezaki, Japan / 56.7% destroyed.

U.S. equivalent: Sioux Falls, SD

Takamatsu, Japan / 67.5% destroyed.

U.S. equivalent: Knoxville, TN

Akashi, Japan / 50.2 % destroyed.

U.S. equivalent: Lexington, KY

Fukuyama, Japan / 80.9% destroyed.

U.S. equivalent: Macon, GA

Aomori, Japan / 30% destroyed.

U.S. equivalent: Montgomery, AL

Okazaki, Japan / 32.2% destroyed

U.S. equivalent: Lincoln, NE

Oita, Japan / 28.2% destroyed

U.S. equivalent: Saint Joseph, MO

Hiratsuka, Japan / 48.4% destroyed

U.S. equivalent: Battle Creek, MI

Tokuyama, Japan / 48.3% destroyed

U.S. equivalent: Butte, MT

Yokkichi, Japan / 33.6% destroyed

U.S. equivalent: Charlotte, NC

Uhyamada, Japan / 41.3% destroyed

U.S. equivalent: Columbus, GA

Ogaki, Japan / 39.5% destroyed

U.S. equivalent: Corpus Christi, TX

Gifu, Japan / 63.6% destroyed.

U.S. equivalent: Des Moines, IA

Shizuoka, Japan / 66.1% destroyed.

U.S. equivalent: Oklahoma City, OK

Himeji, Japan / 49.4% destroyed.

U.S. equivalent: Peoria, IL

Fukuoka, Japan / 24.1% destroyed.

U.S. equivalent: Rochester, NY

Kochi, Japan / 55.2% destroyed.

U.S. equivalent: Sacramento, CA

Shimizu, Japan / 42% destroyed.

U.S. equivalent: San Jose, CA

Omura, Japan / 33.1% destroyed.

U.S. equivalent: Sante Fe, NM

Chiba, Japan / 41% destroyed.

U.S. equivalent: Savannah, GA

Ichinomiya, Japan / 56.3% destroyed.

U.S. equivalent: Springfield, OH

Nara, Japan / 69.3% destroyed.

U.S. equivalent: Boston, MA

Tsu, Japan / 69.3% destroyed.

U.S. equivalent: Topeka, KS

Kuwana, Japan / 75 % destroyed.

U.S. equivalent: Tucson, AZ

Toyohashi, Japan / 61.9% destroyed.

U.S. equivalent: Tulsa, OK

Numazu, Japan / 42.3% destroyed.

U.S. equivalent: Waco, TX

Chosi, Japan / 44.2% destroyed.

U.S. equivalent: Wheeling, WV

Kofu, Japan / 78.6% destroyed.

U.S. equivalent: South Bend, IN

Utsunomiya, Japan / 43.7% destroyed.

U.S. equivalent: Sioux City, IA

Mito, Japan / 68.9% destroyed.

U.S. equivalent: Pontiac, MI

Sendai, Japan / 21.9% destroyed.

U.S. equivalent: Omaha, NE

Tsuruga, Japan / 65.1% destroyed.

U.S. equivalent: Middleton, OH

Nagaoka, Japan / 64.9% destroyed.

U.S. equivalent: Madison, WI

Hitachi, Japan / 72% destroyed.

U.S. equivalent: Little Rock, AK

Kumagaya, Japan / 55.1% destroyed.

U.S. equivalent: Kenosha, WI

Hamamatsu, Japan / 60.3% destroyed.

U.S. equivalent: Hartford, CT

Maebashi, Japan / 64.2% destroyed.

U.S. equivalent: Wilkes Barre, PA

____________________________

Hiroshima, Japan / atomic bomb

U.S. equivalent: Seattle, WA

Nagasaki, Japan / atomic bomb

U.S. equivalent: Akron, OH

____________________________

Sources: Errol Morris, Documentary film,

“The Fog of War: Eleven Lessons From the

Life of Robert S. McNamara,” 2003, Errol

Morris.com; “67 Japanese Cities Firebombed

in World War II,” diText.com; and, Alex

Wellerstein, “Interactive Map Shows Impact

of WWII Firebombing of Japan, If It Had

Happened on U.S. Soil,” Slate.com, March

13, 2014. Note: Some sources say that more

than 100 Japanese cities & towns were

firebombed (see Tanaka in Sources).

_________________________________

Beyond the Errol Morris film, there is also a considerable literature on the firebombing of Japan, which has grown through the 2000s and 2010s. The firebombing of Tokyo, in particular, has received specific attention, as noted in books cited above, but also in periodical sources, some listed below in the reference section. American historian Mark Selden, for example, has written extensively about the Japanese firebombing episode and other wartime air campaigns, noting of the August 1945 Tokyo raid in a 2007 paper for The Asia-Pacific Journal:

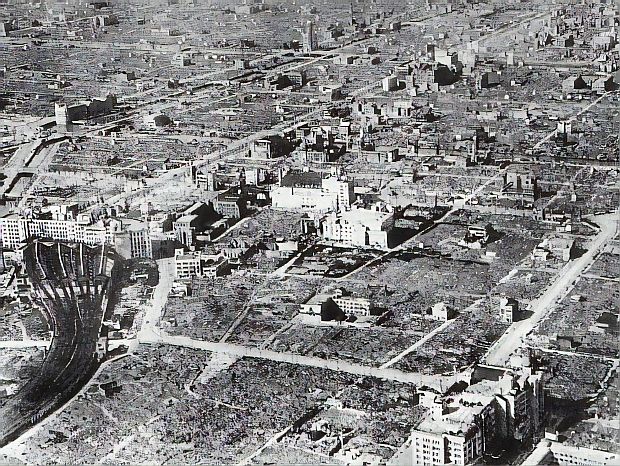

…The full fury of firebombing and napalm was unleashed on the night of March 9-10, 1945 when LeMay sent 334 B-29s low over Tokyo from the Marianas [islands]. Their mission was to reduce the city to rubble, kill its citizens, and instill terror in the survivors, with jellied gasoline and napalm that would create a sea of flames. …[T]he bombers…carried two kinds of incendiaries: M47s, 100-pound oil gel bombs, 182 per aircraft, each capable of starting a major fire, followed by M69s, 6-pound gelled-gasoline bombs, 1,520 per aircraft, in addition to a few high explosives to deter firefighters. …Whipped by fierce winds, flames detonated by the bombs leaped across a fifteen square mile area of Tokyo generating immense firestorms that engulfed and killed scores of thousands of residents.

One photograph of devastated Tokyo, Japan following the U.S. March 9-10, 1945 firebombing raid by B-29s, showing, in part, an industrial area along the Sumida River. Some 16 square miles of the city were razed by incendiary and other strikes. AP photo.

Mark Selden further notes a first-hand report of a police cameraman named Ishikawa Koyo, who described the streets of Tokyo as “rivers of fire” where people “blazed like ‘matchsticks’ as their wood and paper homes exploded in flames.” Koyo further reported that “under the wind and the gigantic breadth of the fire, immense incandescent vortices rose in a number of places, swirling, flattening, sucking whole blocks of houses into their maelstrom of fire.”

People died from radiant heat and direct flames, falling debris, oxygen deficiency, carbon monoxide poisoning, by trampling of stampeding crowds, and by drowning, as thousands jumped into canals and other water bodies attempting to escape the flames. Tokyo firebombing survivor Haruyo Nihei, at age 83 when interviewed by CNN, reported she was 8 years old at the time of the firebombing when she and her father were swept up into a mass panic on the streets during the bombing. They fell to the ground as others piled on top of them, and survived only by virtue of being insulated by those who burnt to death on top of them.

Photograph of Japanese on a road through Tokyo taken some time after the March 1945 U.S. firebombing of the city.

Some estimates of the dead from that one raid on Tokyo run as high as 100,000 or more men, women and children, with a million more injured and another million left homeless – though Japanese and American estimates on the toll of the raid vary, some with lower numbers. Still, the firebombing of Tokyo on the night of March 9–10, 1945 is the single deadliest air raid in history, with a greater area of fire damage and loss of life than either of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima or Nagasaki. But Tokyo would endure more firebombing — two more raids in April and two in May, adding more square miles to the city’s burnt-out destruction.

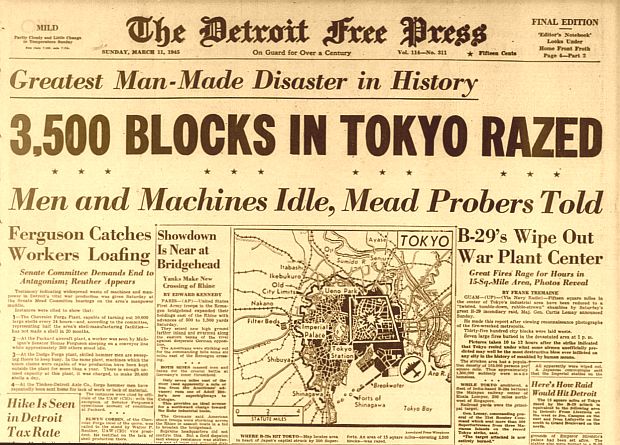

March 11th, 1945 headlines from “The Detroit Free Press” reporting on the first U.S. firebombing run by B-29s over Tokyo, Japan. Smaller headline over news story at right notes: “Great Fires Rage for Hours in 15-Sq-Mile Area, Photos Reveal”.

Some surviving B-29 crew members would later tell the New York Times Magazine in March 2020 that a few pilots voiced objection to the firebombing missions but were pressured to go along, while some crew members would recall the foul smell of the firebombings that would rise up and wash over their planes in updrafts from below. “We hated what we were doing,” said B-29 crewman, Jim Marich, of the civilian firebombings, “but we thought we had to do it. We thought that raid might cause the Japanese to surrender.” Marich was one of the B-29 airmen interviewed by the Times who flew on the firebombing of Tokyo in March 1945.

Others, however, had no qualms about the U.S. firebombing Japanese cities, citing Japan’s own acts of horror, from the Pearl Harbor sneak attack and American prisoner beheadings, to Japan’s own thousands of civilian bombings in China – of Shanghai, Wuhan, Chongqing, Nanjing, and Canton – between 1937 and 1943. Sparing additional American and Japanese lives in an otherwise necessary American invasion of Japan to end the war is cited as well – a defense also raised for the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Yet the debate on all of this continues to this day.

CNN map of Japan showing 10 Japanese cities that were firebombed with percentage of area destroyed in each.

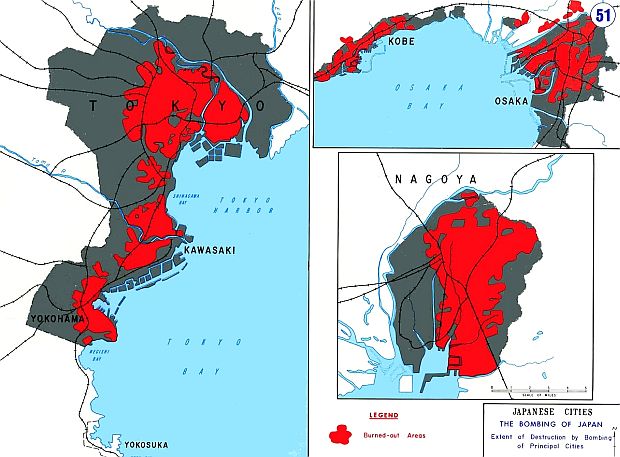

In addition to Tokyo, other Japanese cities were also hard hit. Osaka, the second largest city in Japan, with more than 3 million residents and a key industrial, shipping, rail, and war-materials center, was firebombed by three waves of B-29s in nighttime raids over a three-and-a-half hour period on March 13, 1945. According to a summary at Wikipedia, each wave targeted a distinct area of the city. The first wave of 43 U.S. bombers arrived from Saipan; a second group of 107 B-29s came from Tinian, and a third wave of 124 bombers flew in from Saipan. In all, 274 B-29s destroyed more than 8 square miles of the city, leaving nearly 4,000 residents dead and another 678 missing. Osaka would be bombed several more times in June and July and a final time in August 1945, though not all of these raids used firebombs. A total of more than 10,000 residents of Osaka were killed in eight raids by U.S. bombers.

This photo shows damage in the Namba area of Osaka following 1945 U.S. bomber raids. The Nankai Namba rail station is visible at left.

The Japanese city of Kobe was attacked by 331 B-29s on the night of March 16/17, 1945, with a resulting firestorm that destroyed roughly half its area, killing 8,000 and leaving 650,000 homeless. On May 13, 1945, a fleet of 472 B-29s struck Nagoya by day, followed by a second raid at night on May 16 by 457 B-29s. The two raids on Nagoya killed 3,866 Japanese and rendered another 472,701 homeless. A daylight incendiary attack on Yokohama on May 29 sent 517 B-29s to that city escorted by 101 P-51s fighter planes. This force was intercepted by Japanese Zero fighters, sparking an intense air battle in which five B-29s were shot down and another 175 damaged. The 454 B-29s that reached Yokohama struck the city’s main business district and destroyed 6.9 square miles of buildings with more than 1,000 Japanese killed.

Maps showing, in red, the proportion of key Japanese cities that were burnt out by the U.S. firebombings. At left, the damage in 3 cities on Tokyo Bay is shown: Tokyo, Kawasaki and Yokohama. On the maps at right, two cities on Osaka Bay are shown at top, Kobe and Osaka, and at lower right, the burnt-out area of Nagoya. Wikipedia.org.

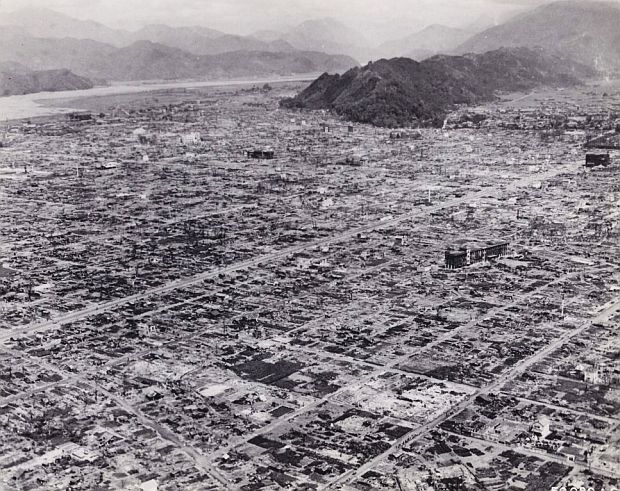

The firebombing of dozens more Japanese cities continued through June and July of 1945, among these were smaller Japanese cities with populations ranging from 62,280 to 323,000. On the night of 27/28 July, six B-29s dropped leaflets over 11 Japanese cities warning that they would be attacked in the future. And on July 28, six of these cities were attacked – Aomori, Ichinomiya, Tsu, Uji-Yamada Ogaki and Uwajima. During August 1945 further large-scale raids against Japanese cities began. More than 830 B-29s staged one of the largest raids of World War II on August 1st when the cities of Hachioji, Mito, Nagaoka and Toyama were targeted, suffering extensive damage. On this raid, Toyama, a large producer of aluminum, was especially hard hit, as McNamara noted in the “Fog of War,” with some 99 percent of its area destroyed after 173 B-29s dropped incendiary bombs on the city.

August 1, 1945. Nighttime aerial view of fiery scene below as much of Toyama, Japan, a city of 100,000 and a large producer of aluminum, burns to the ground after 173 American B-29 bombers dropped incendiary bombs on the city.

As the bombing campaign continued and the most important cities were destroyed, the bombers were then sent out against smaller and less significant cities. Many of these cities were not defended by anti-aircraft guns and Japan’s night-fighter force was ineffective. In this phase of the campaign, on most nights, four cities were attacked each night. According to Wikipedia, sixteen multi-city incendiary attacks of this kind were conducted by the end of the war (an average of two per week), targeting some 58 cities. Some of the incendiary raids were coordinated with precision bombing attacks during the last weeks of the war in an attempt to force a Japanese surrender. Then came the nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 6th and 9th, respectively, which finally moved Japan to surrender on August 15, 1945. Overall, by one calculation, the U.S. firebombing campaign, exclusive of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, killed more than 300,000 people

Photo of Shizuoka, Japan, sometime after being firebombed on June 19, 1945 by 137 B-29 bombers which attacked in two waves from east and west, so as to trap the population within the center of the city, between the mountains and the sea, dropping 13,211 incendiary bombs. The resultant firestorm destroyed most of the city (66.1%), then with an estimated population of 212,000, comparable in size to Oklahoma City, OK. Two B-29s collided mid-air during the operation, resulting in the deaths of 23 Americans. See: “Bombing of Shizuoka in World War II,” Wikipedia.

Further research and writing on the WWII firebombing of Japanese cities – and on the American city comparisons – have been made by military historians, geographers, and others. Several of these are listed in Sources at the end of this story. One offering at Slate.com includes a series of interactive maps plotting out a “what if” scenario, mapping the locations of the comparable American cities with the bombed-out proportions of their Japanese counterparts. The Slate piece – by Alex Wellerstein – also notes, importantly, that Japan is a much smaller country than the U.S. (about the size of Montana), and so, the effects of the firebombings there were magnified all the more.

The Errol Morris film, meanwhile, also focuses on Robert McNamara during the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962 and the Vietnam War. The film generally received positive reviews and high praise, but not from all quarters. Public opinion on McNamara over the years has been sharply divided, and he has fierce critics. Still, in his later years, as with the 22 hours of interviews and filming he did with Morris, McNamara spent years writing, probing, and public speaking trying to come to terms with his and the nation’s military involvements (some of his books and those of others about him are listed below in Sources). No doubt McNamara was trying to exorcize demons and guilt that he could never completely purge as he sought to explain his actions and policy-making, for which many would never forgive him. But at least he tried, and did so publicly.

1965. U.S. Secretary of Defense, Robert McNamara, giving a briefing during the Vietnam War, with map of the region behind him.

See also at this website, “The Pentagon Papers,” a freedom-of-the-press story involving Vietnam War-era secret documents and other papers, some of which then Defense Secretary Robert McNamara commissioned for an historic review of that war. A Steven Spielberg film on the topic is also part of this story, along with involvement of the Washington Post, New York Times, and famous whistle-blower, Daniel Ellsberg.

Thanks for visiting – and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research, writing and continued publication of this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

____________________________________

Date Posted: 29 November 2020

Last Update: 26 July 2023

Comments to: jackdoyle47@gmail.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Firebombing Japan: 67 Cities, 1945,”

PopHistoryDig.com, November 29, 2020.

____________________________________

Books at Amazon.com…

Sources, Links & Additional Information

Errol Morris, documentary film, “The Fog of War: Eleven Lessons From the Life of Robert S. McNamara,” 2003, ErrolMorris.com.

Transcript of Errol Morris film, “The Fog of War,” ErrolMorris.com.

“The Fog of War,” Wikipedia.org.

“Pacific War,” Wikipedia.org.

“Air Raids on Japan,” Wikipedia.org.

“Bombing of Tokyo (10 March 1945),” Wiki-pedia.org.

U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey, “Effects of Air Attack on Urban Complex Tokyo-Kawasaki -Yokohama,” 1947.

“McNamara on Bombing of Japan”(cut.mp4), YouTube.com, Posted by: profgunderson, January 18, 2010.

“67 Japanese Cities Firebombed in World War II,” diText.com.

Conrad C. Crane, American Airpower Strategy in World War II: Bombs, Cities, Civilians, and Oil, Lawrence, 2016.

R. W. Apple Jr., “McNamara Recalls, and Regrets, Vietnam,” New York Times, April 9, 1995.

Kenneth P. Werrell, Blankets of Fire: U.S. Bombers Over Japan During World War II (Smithsonian History of Aviation and Spaceflight Series), April 1996.

“Bombing of Osaka,” Wikipedia.org.

Alex Wellerstein, “Interactive Map Shows Impact of WWII Firebombing of Japan, If It Had Happened on U.S. Soil,” Slate.com, March 13, 2014.

“The Fog of War: Eleven Lessons From the Life of Robert S. McNamara,” Metacritic.com (87 metascore, based on 36 critic reviews), 2003.

User Reviews, “The Fog of War: Eleven Lessons from the Life of Robert S. McNamara” (2003), IMDB.com.

“The Fog of War,” The Charlie Rose Show, November 11, 2003 (Guests: Director Errol Morris and former Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara describe their documentary “The Fog of War” which follows the life of McNamara and his experience in modern warfare), Transcript, CharlieRose.com.

Jonathan Curiel, “In New Documentary, Old Hawk Rethinks Roles in Vietnam and WWII,” San Francisco Chronicle/SFgate.com, Janu-ary 21, 2004.

“An Appreciation of Robert McNamara,” The Charlie Rose Show, YouTube.com.

“Robert McNamara,” alchetron.com.

Joseph Coleman, Associated Press, “1945 Tokyo Firebombing Left Legacy of Terror, Pain,” CommonDreams.org, March 10, 2005.

A.C. Grayling, Among the Dead Cities: The History and Moral Legacy of the WWII Bombing of Civilians in Germany and Japan, New York, 2006.

Mark Selden, “A Forgotten Holocaust: U.S. Bombing Strategy, The Destruction of Japanese Cities and The American Way of War From World War II to Iraq,” Asia-Pacific Journal, May 2, 2007, Volume 5 | Issue 5

Tim Weiner, “Robert S. McNamara, Architect of a Futile War, Dies at 93,” New York Times, July 6, 2009.

Laurence M. Vance, “Bombings Worse Than Nagasaki and Hiroshima,” The Future of Freedom Foundation, August 14, 2009.

Tony Long, “March 9, 1945: Burning the Heart Out of the Enemy,” Wired, March 9, 2011.

David Fedmana and Cary Karacasb, “A Cartographic Fade to Black: Mapping the Destruction of Urban Japan During World War II,” Journal of Historical Geography, Volume 38, Issue 3, July 2012.

Alison Bert, DMA, “Maps Reveal How Japan’s Cities Were Destroyed During World War II. Essay on Incendiary Bombings Awarded 2012 Best Paper Prize by the Journal of Historical Geography,” Elsevier.com, March 18, 2013.

Associated Press, “Deadly WWII Firebomb-ings of Japanese Cities Largely Ignored,” Tampa Bay Times, March 9, 2015.

Mark Selden, “American Fire Bombing and Atomic Bombing of Japan in History and Memory,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Decem-ber 1, 2016, Volume 14 | Issue 23.

“Bombing of Osaka,” Wikipedia.org.

“Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nag-asaki,” Wikipedia.org.

“Hellfire on Earth: Operation Meetinghouse,” NationalWW2Museum.org, March 8, 2020.

Brad Lendon and Emiko Jozuka, “History’s Deadliest Air Raid Happened in Tokyo During World War II and You’ve Probably Never Heard of It,” CNN.com, March 8, 2020.

John Ismay, “‘We Hated What We Were Doing’: Veterans Recall Firebombing Japan. American Airmen Who Took Part in the 1945 Firebombing Missions Grapple With the Particular Horror They Witnessed Being Inflicted on Those Below,” New York Times Magazine, March 9, 2020.

Motoko Rich, “The Man Who Won’t Let the World Forget the Firebombing of Tokyo. As a Child, Katsumoto Saotome Barely Escaped the Air Raids over Tokyo That Killed as Many as 100,000 People. He Has Spent Much of His Life Fighting to Honor the Memories of Others Who Survived,” New York Times Magazine, March 9, 2020.

Press Release, Sony Pictures Classics Presents, “The Fog of War: A Film by Errol Morris” (backgrounder w/ Director’s Statement and more), SonyClassics.com, 28 pp, 2003.

“The Fog of War,” Part 1 (video, 57:43), DailyMotion.com.

“The Fog of War,” Part 2 (video, 48:51), DailyMotion.com.

____________________________________