Thousands of miles of fossil fuel pipelines of all kinds – crude oil, gasoline, natural gas, and related petrochemicals – crisscross the U.S. and other nations around the world. Sometimes these pipelines leak, explode, or cause raging fires that can endanger public health and safety, pollute the environment, and/or cause millions of dollars in property damage. Such was the case on June 10th, 1999, when a leak of 277,000 gallons of gasoline from an underground pipeline at Bellingham, Washington ignited and caused a massive explosion and fireball that killed three boys, terrorized a city of 75,000, and left a 1.3 mile scorched-earth corridor of environmental devastation. The Seattle Times newspaper ran a front-page story on the calamity, with a large and graphic photo and headline that read, “Everything is Dead,” quoting a local official on the environmental carnage.

June 12, 1999 front-page headline of The Seattle Times exclaims, “Everything is Dead,” referring to the devastation along a charred Whatcom Creek following Olympic Pipeline explosion & fireball that killed 3 boys. Aerial photo shows scorched path of fireball route along creek & through park. Top inset also shows headline of inside story, “Olympic Inspection Raised Questions.”

The explosion and fireball occurred on a beautiful early summer day, finding its ignition source in a most unlikely of places: Whatcom Falls Park, in Bellingham, a popular park where two salmon streams converged – Whatcom and Hanna Creeks. However, slicing through this park, beneath its creeks, was the Olympic Pipeline. This pipeline, on its north-south route, carried hundreds of thousands of gallons of petroleum fuels daily between pumping stations and refineries in northwest Washington state. But on this June afternoon the pipeline had leaked gasoline — enough to form a layer approximately three inches thick on the surface of the creeks over a distance of about 1.3 miles.

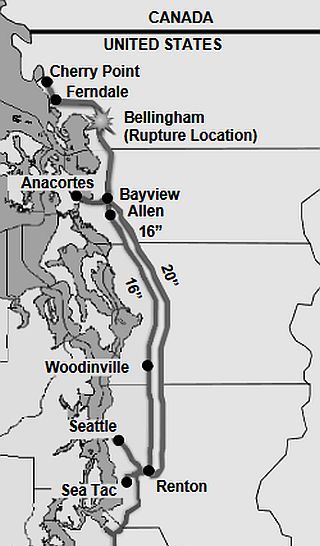

Bellingham location in Washington state.

Whatcom Falls Park is a large 241-acre public park encompassing the Whatcom Creek gorge, running directly through the heart of the city. It has four sets of waterfalls and several miles of walking trails, and is a hub of outdoor activity connecting and defining several different neighborhoods of Bellingham. Popular activities during warmer weather include swimming, fishing, and strolling along the park’s walking trails

Map showing pipeline routes, where explosion occurred at Bellingham, as well as refinery locations at Cherry Point and Anacortes, pumping locations, and delivery locations.

One 16-inch-diameter pipeline – the accident pipeline – was moving product from an Atlantic Richfield Company (ARCO) oil refinery and pumping station near Cherry Point, Washington to a Tosco Company oil storage facility near Renton, Washington, a distance of about 107 miles.

This pipeline and another were operated remotely at a computer-assisted control center located in Renton. At the time of the accident, Olympic was jointly owned by Equilon Pipeline Company LLC (Shell and Texaco), Atlantic Richfield, and GATX Terminal Corporation, with Equilon under contract to manage the operation of the pipeline.

Equilon, in fact, was a new entity, formed by Shell and Texaco in January 1998, with Shell holding a 56- percent ownership stake, and Texaco, 44 percent. Equilon, in effect, brought together Shell and Texaco “downstream” refining and marketing properties in the West and Midwest, which included terminals, refineries, and gas stations. One of the Equilon properties was an oil refinery at Anacortes, WA. At that refinery, in November 1998, six workers were killed in an horrific explosion, for which Equilon was found culpable, fined $4.1 million by the state, and after admitting responsibility for the accident, agreed to a wrongful death settlement of $45 million in a lawsuit brought by the families of the six men killed.

10 year-old, Stephen Tsiorvas. |

10 year old, Wade King. |

Liam Wood, fly fisherman. |

Note: "Gone fishing." |

Boys in the Park

As noted earlier, Whatcom Falls Park in Bellingham is a popular recreation destination in the Bellingham area, especially in summer. On Thursday, June 11, 1999, two ten-year-old boys, friends Wade King and Stephen Tsiorvas, were having some fun in Whatcom Falls Park, exploring its woods and streams as boys that age love to do. They were passing the afternoon there, sometime after 3:00 p.m. or so.

Also in the park that day was 18 year-old Liam Wood, a soon-to-be grad of Sehome High School. Liam loved fly fishing and had gone to the park, leaving a note at home telling his parents of his whereabouts: “Guys, I’m fishing. Will be back before dark. Homework is done [heart symbol]. Liam.”

Unbeknownst to any of these boys, the leaked gasoline was all around them, as fumes and liquid had infiltrated the streams.

Meanwhile, in the control rooms for the Olympic Pipeline operators, some anomalies were noticed during the 3:00-4:00 p.m. period. Alarms had sounded and pumping at one station had shut down. Something seemed amiss. However, the operators couldn’t quite figure out what the problem was. What had actually happened by about 3:20 p.m. or so – and unknown to anyone at this point – was that a rupture had occurred in the Olympic Pipeline near the waterworks plant at Bellingham adjacent to Whatcom Falls Park. In latter accounting it was learned that malfunctioning pumps and valves in the Olympic system for this line also contributed to the rupture, as pressure within the line had increased during the event as a result of these problems. In any case, at about 3:25 p.m. that afternoon, gasoline began spilling into Hanna Creek just above its confluence with Whatcom Creek and was soon moving into Whatcom Creek as well.

Back at the control center, there was some concern since the pipeline had shut itself down between Cherry Point and Renton. Still, by 4:15 pm or so, gasoline transfer from Cherry Point was restarted. About ten minutes later, approximately 4:24 p.m, a woman driving across Woburn Street bridge at Whatcom Creek called 911 saying she smelled an “incredible odor that made breathing difficult.” Shortly thereafter, a Bellingham resident living near Whatcom Creek also called 911 reporting a strong petroleum odor and a discoloration of the creek.

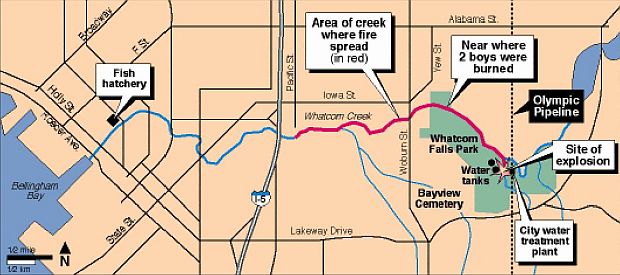

Map shows Whatcom Falls Park, the North-South route of Olympic Pipeline crossing stream and park (dotted line), the leak/explosion site, and the extent of Whatcom Creek that burned as it flowed in a westerly direction (in red) toward Bellingham proper and Bellingham Bay.

At the control center in Renton at about 4:29 p.m., leak detection software had activated an alarm. An Olympic Pipeline employee in Bellingham called 911 from the Woburn Street bridge, reporting gasoline fumes. He then called the Olympic Pipeline control room in Renton to notify them.

Olympic Pipe Line controllers began closing valves to isolate the rupture. Back in Bellingham, police and fire crews were closing roads around the creek and called in a hazardous materials team to investigate. It was then about 4:34 p.m. Some arriving fireman reported seeing fumes rising from the creek. According to one, “the creek had turned yellow, a ‘river of gasoline’.” By 4:46 radio stations began broadcasting emergency messages, urging people to stay away from the creek. And about ten minutes later, evacuations were called for in areas within 200 feet of the creek. By 4:57 p.m. Olympic controllers called 911 dispatch to report a “possible release of product into Whatcom Creek.”

Meanwhile, back in Whatcom Falls Park, ten year-old explorers, Wade King and Stephen Tsiorvas, had found an old discarded butane cigarette lighter. And as ten year-old boys are want to do, they began playing with it, and flicking it, which shortly became the ignition source for the fumes and leaked gasoline that had been accumulating around them.

June 10, 1999. Smoke from pipeline explosion at Whatcom Creek in Bellingham, WA rises ominously after leaked gasoline ignited, killing three boys. (Bellingham Herald ).

At 5:02 p.m. the leaked gas ignited on Whatcom Creek resulting in a huge explosion with ensuing fireball that rolled along the ground and streambed for more than a mile in a westerly direction toward Bellingham. As it went the fireball incinerated creek bed, nearby vegetation, and practically everything in its path.

June 10, 1999. A somewhat wider area perspective on the huge smoke cloud rising from the Olympic Pipeline explosion at Bellingham, Washington.

A huge billowing smoke cloud rose high into the sky – six miles high, according to one account — and visible for miles. Back along the creek, pockets of gasoline created successive explosions, and emergency crews would continue to fight spot fires for five days following the explosion.

Scene along Whatcom Creek shortly after pipeline explosion. |

Portion of scorched-earth path along Whatcom Creek following June 1999 pipeline leak & explosion in Bellingham, WA. |

The boys, meanwhile, had jumped into the creek trying to save themselves, but their skin was severely burned, though walking and talking immediately after the accident, and conscious during the ambulance ride to the local hospital.

The two boys were later airlifted to a Seattle hospital burn unit but died the next day.

Liam Wood, the 18-year-old fly fisherman, had drowned after he was overcome by the gasoline vapors while fly-fishing and passed out, falling into the stream where he drowned.

Authorities say that while the younger boys had touched off the inferno, they may have saved countless other lives. The disaster could have been much worse had the gasoline moved further downstream in a westerly direction, toward Bellingham.

But fortunately, the fire and explosions were confined to the park and much of the gasoline had burned up before it could follow the creek through a more populated residential area and possibly into downtown Bellingham and beyond, into Bellingham Bay.

Still, some gasoline had migrated into the city’s sewer system, and for an hour or so, according to some reports, vapors were at explosive levels at some locations. Bellingham police had begun evacuating businesses. And the U. S. Coast Guard, concerned the fuel could ignite dock pilings and vessels, closed Bellingham Bay for a one-mile radius from the mouth of Whatcom Creek.

In the aftermath, the charred scene reminded some of a war zone. “It looked like…they laid down napalm,” said Bellingham police officer Dac Jamison, a Vietnam War vet, describing the blackened park and streambed later.

The burn zone encompassed 26 acres, with the fire destroying 2.5 miles of riparian vegetation along the stream beds, 100,000 fish, and other aquatic organisms and wildlife. The smoke from the blaze had closed Interstate 5 to traffic for several hours the evening of the accident. The explosion and fire also knocked out electric power for hours affecting 4,000 people and crippled Bellingham’s water supply for nearly a week, having damaged part of the city’s water treatment and distribution system.

During the incident, Whatcom County officials implemented a disaster plan with evacuations, also opening an emergency operations center. For nearly two years following the explosion, a 37-mile section of the troubled pipeline would be shut down.

Hearings, Reports, Lawsuits

One of the Congressional hearings held on the Olympic Pipeline disaster, this one by a U.S. House of Representatives subcommittee in Washington, D.C. on October 27, 1999. It includes 227 pages of testimony and submissions from more than a dozen witnesses.

On July 28, 1999, the parents of Wade King and Stephen Tsiorvas – the two boys killed in the pipeline inferno — filed a wrongful-death lawsuit in Whatcom County Superior Court naming Olympic Pipe Line, Equilon, and three Olympic employees as defendants.

U.S. Congressional hearings were also held — one in Washington D.C. before a House subcommittee on October 27, 1999, and another by a U.S. Senate committee on March 13, 2000, this one a field hearing held in Bellingham. Both of Washington’s U.S. Senators, some of its U.S. and state representatives, and a number of other witnesses appeared at the hearings or issued statements for the record.

On March 28, 2000, Washington Governor Gary Locke signed into law the Washington Pipeline Safety Act, which included authority for the Washington State Utilities and Transportation Commission to inspect some 2,500 miles of Washington’s intrastate pipelines and oversee the state’s pipeline-safety program.

Among the first federal agencies to formally report on the Bellingham pipeline explosion was the U.S. Office of Pipeline Safety(OPS), issuing its findings in June 2000. According to OPS, Equilon Enterprises operated the Olympic pipeline in an unsafe manner and violated pipeline safety standards by: failing to take precautions to prevent damage to the pipeline, failing to test safety equipment, and not adequately training employees. For these failures, OPS announced it would seek a record fine of more than $3 million against the Olympic Pipeline Company.

June 3, 2000. Portion of New York Times story on Office of Pipeline Safety report & proposed fine.

A November 2001 report and investigation by the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) on the Olympic Pipe Line explosion, reviewed the line’s history, operation, and technical controls. The NTSB found a series of errors that led to the pipeline rupture, placing most blame on Olympic for inadequately inspecting work around the pipeline, allowing repeated pressure surges on the line, and failing to repair damaged sections. The pipeline had been dinged and dented in 1994 by a construction company during an excavation for a water treatment plant project. And as noted by NTSB, although Olympic had done an analysis of its entire system in 1997 — when it found “anomalies” in the pipeline section that later ruptured – its engineers at the time failed to do a required excavation, nor did the company inform regulators.

By April 10, 2002, the wrongful death lawsuit brought by the King and Tsiorvas families was resolved with an out-of-court settlement. Olympic and Equilon agreed to pay the families of King and Tsiorvas $75 million. The family of Liam Wood reached a separate, undisclosed settlement with the companies.

Cover of the National Transportation Safety Board report on the Bellingham pipeline explosion. Click for copy.

Under the plea agreement, the companies agreed to pay a record $112 million to settle all federal criminal fines and most civil claims against them. According to U. S. Attorney John McKay, the pleas marked the first time a pipeline company had been convicted under the 1979 Hazardous Liquid Pipeline Safety Act.

The State of Washington also levied civil penalties – $2.5 million on Olympic Pipe Line and $5 million on Shell. All told, Olympic, Equilon, and their various corporate owners and partners faced settlements totaling more than $187 million.

One positive outcome of Olympic Pipe Line explosion was the creation of the Pipeline Safety Trust, which at the time was one of a few pipeline safety watchdog groups that would work to improve pipeline regulation. On June 18, 2003, U.S. District Judge Barbara Rothstein ordered that $4 million of the criminal fines imposed on the industry be awarded as an endowment to fund the Pipeline Safety Trust. The judge noted at the time that the award was small and the task formidable – like “Bambi taking on Godzilla.” Still, she encouraged the industry to listen to and work with the Pipeline Safety Trust so tragedies like Bellingham did not happen again.

Since then, the Pipeline Safety Trust, based in Bellingham, has worked effectively with citizen groups, public officials, and the pipeline industry on safety and regulatory issues.

In Washington, D.C., federal reform of pipeline safety law in Congress was sought shortly after the Bellingham explosion of June 1999, followed in August 2000 by an El Paso natural gas pipeline explosion in New Mexico that killed 12 campers – the twin tragedies then providing a powerful impetus for reform. While the Clinton Administration and others in Congress had introduced bills for reform in 1999 and 2000, it would not be until December 2002 that Congress would pass, and President George Bush would sign, the Pipeline Safety Improvement Act of 2002 (H.R. 3609). Since then, subsequent amendments to federal law have been made. In 2021, the Biden Administration increased funding for pipeline safety while bringing new regulatory oversight to natural gas gathering lines.

Incidents Continue

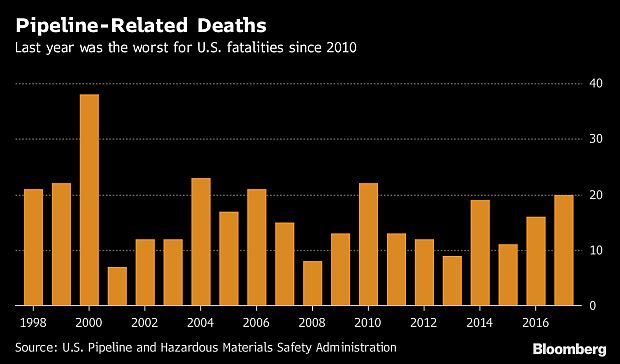

Yet, despite improvements to pipeline safety law and regulation, pipeline leaks, spills, and explosions continue to occur. Hundreds of deaths and thousands of injuries have resulted from pipeline incidents in the U.S. since 1998.

As reported by Bloomberg.com in November 2016, “over the last thirty years, just under 9,000 significant pipeline-related incidents have taken place nationwide,” according to data from the U.S. Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration. And as Bloomberg further reported on the damage involved:

…CityLab mapped out all significant pipeline accidents between 1986 and 2016, based on data compiled by Richard Stover, an environmental advocate and former research astronomer at the University of California, Santa Cruz. According to Stover, these accidents have resulted in 548 deaths, 2,576 injuries, and over $8.5 billion in financial damages.

Bloomberg graphic of “Pipeline-Related Deaths,” 1998-2017, based on data from the U.S. Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration.

Back in Whatcom County, meanwhile, the memory and legacy of the 1999 explosion – or at least the network of fossil fuels-wary citizens and officials that rose in civic leadership around that and related issues, seems to be still at work. In June 2021, the county became the first in the nation to adopt a measure that bans the construction of new refineries, coal-fired power plants and other fossil fuel-related infrastructure. The ordinance also places new restrictions on existing fossil fuel facilities, requiring that any new fossil- related emissions resulting from expansions be offset.

For additional “oil & the environment” stories at this website see any of the following: “Burning Philadelphia,” a story about the 1975 Gulf Oil Co. refinery fire in that city; “Santa Barbara Oil Spill” about the 1969 Union Oil offshore oil well blow-out and pollution of California’s coastline; “Texas City Disaster,” about BP’s 2005 Texas City, TX oil refinery explosion and fire that killed 15 workers and injured another 180; “Barge Explodes in NY,” about a Bouchard gasoline transport barge docked at an ExxonMobil depot that exploded into a giant fireball in 2003, polluting waterways in the New York city area, shutting down water traffic, and shaking up communities for miles around; “Inferno at Whiting: 1955,” about an eight-day catastrophic Standard Oil/Amoco oil refinery explosion and fire near Chicago; “Oil Fouls Montana,” profiling an oil pipeline leak that fouled the Yellowstone River in January 2015; and, “Deepwater Horizon, Film & Spill,” a story about the making of the 2016 Hollywood film on the BP offshore oil rig disaster, plus a recap of the politics, media coverage, and corporate maneuvering during the real BP oil spill in the Gulf.

Thanks for visiting – and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research and writing at this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

____________________________________

Date Posted: November 18, 2021

Last Update: November 18, 2021

Comments to: jdoyle@pophistorydig.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Pipeline Fireball, Bellingham, WA: 1999,”

PopHistoryDig.com, November 18, 2021.

____________________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

John Harris and Cathy Logg, “Gas Pipeline Explodes,” Bellingham Herald, June 11, 1999, p. 1.

Scott Sunde, “Blast Ignites River of Fire,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, June 11, 1999, p. 1.

Keiko Morris, Janet Burkitt, Jim Brunner, Jack Broom, “3 Die, Including 2 Boys, When Fireball Erupts in Bellingham Gas-Line Explosion,” Seattle Times, June 11, 1999.

Keiko Morris, Janet Burkitt, Jim Brunner, Jack Broom, “Fire Takes Young Lives — Cause Investigated; Pipeline Has Anacortes Refinery Tie,” Seattle Times, June 11, 1999.

Seattle Times Staff, “‘Everything Is Dead’ — Bellingham Fireball Turned Dreams Of Reviving Salmon Habitat To Ashes — How Gas Leaked and How It Ignited Remain Mystery,” Seattle Times, June 12, 1999. p.1.

B Acohido and E. Sorensen, “Olympic Inspection Raised Questions,” Seattle Times, June 12, 1999.

S. Becker and S. Clark, “Case Study: Pipeline Explosion, Bellingham, Washington, June 10, 1999,” Case Studies of Transportation Accidents Involving Hazardous Materials, Module 9, UA.edu.

Randall Carroll, Fire Chief, City of Bellingham, Washington, “Olympic Pipe Line Pipeline Rupture and Fire,” PowerPoint presentation.

Nicole C. Oliver, “Whatcom Creek Restor-ation” (cover story), Whatcom Watch Online, July 1999, Volume 8, Issue 7.

B. Dudley, “Public Adamant in Call to Improve Pipeline Safety,” Seattle Times. September 9, 1999.

Kim Murphy, “Problems in the Pipelines,” Los Angeles Times, September 15, 1999.

B. Dudley, “Will Impact of Pipeline Burst Hit Home Values?,” Seattle Times. September 19, 1999.

B. Dudley, “Congress to Hold Hearing on Bellingham Pipeline Leak,” Seattle Times. October 8, 1999.

J.V. Grimaldi, “NTSB Ties Rupture to Water-Line Project,” Seattle Times. October 27, 1999.

Associated Press, “Explosion Still Taking Human Toll, Team Is Told,” Seattle Times, November 17, 1999.

S. Miletich, “Olympic Pipe Line Blames Construction Firm for Deadly Rupture,” Seattle Times, February 11, 2000.

“Governor Signs Pipeline Safety Act,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, March 29, 2000, p. B-2.

“Law Boosts Pipeline Safety in State,” Seattle Times, March 29, 2000.

“RSPA Wants to Fine Olympic Pipeline $3 Million,” Oil & Gas Journal / OGI.com, June 2, 2000.

Associated Press, “Operator of Pipeline Faces a Record Fine,” New York Times, June 3, 2000, p. A-9.

U. S. General Accounting Office (GAO), Report to the Ranking Minority Member, Committee on Commerce, House of Representatives, “Pipeline Safety: The Office of Pipeline Safety Is Changing How It Oversees the Pipeline Industry,” May 2000 (includes appendix on the status, at that time, of the investigation of the Bellingham explosion).

“Olympic Pipeline Explosion: A Retrospec-tive,” The Planet, Spring/Summer 2000 (a publication of Huxley College of Environ-mental Studies), 64pp [PDF at: Pipeline Safety Trust /pstrust.org.]

Christian Davenport, “Longhorn Debate Calls Attention to Pipelines,” Austin American-Statesman [re: Texas pipelines], April 16, 2000.

Jim Brunner, “Equilon Settles in ’98 Refinery Blast” (re: 1998 Anacortes refinery explosion that killed 6 workers], Seattle Times, January 20, 2001.

Steven A. Holmes, “Pipeline in Fatal Accident Undergoes a Test Pumping,” New York Times, January 27, 2001, p. A-9.

Associated Press, “Pipeline Lawsuits: Olympic, Equilon Fight Each Other in Court,” KitsapSun.com, July 29, 2001.

Paul Shukovsky, “Criminal Indictments in Deadly Pipeline Explosion,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, September 13, 2001.

United Press International, “Pipeline Firms Charged in Blast Near Seattle,” UPI.com, September 14, 2001.

Matthew Preusch, National Briefing | North-west: Washington: “U.S. Charges In Blast,” New York Times, September 15, 2001, p. B-4.

Scott Sunde, “Not-Guilty Pleas in Pipeline Blast Case,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Sep-tember 28, 2001, p. B-1

Matthew Preusch, National Briefing | North-west: Washington: “Company To Pay $75 Million In Deaths,” New York Times, April 11, 2002, p. A-31.

National Transportation Safety Board, Pipeline Rupture and Subsequent Fire in Bellingham, Washington, June 10, 1999. Pipeline Accident Report, NTSB/PAR-02/02, Washington, D.C., 2002.

Tracy Johnson, “$75 Million Settlement Won’t End Their Fight for Pipeline Safety. Families of 2 Boys Killed in Bellingham Fire Promise to Continue Pushing,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, April 10, 2002.

“Pipeline Explosion: State Fines Companies for Bellingham Rupture,” KitsapSun.com, June 6th, 2002.

Associated Press, National Briefing | Nort-hwest: Washington: “Blame In Pipeline Blast,” New York Times, October 10, 2002, p. A-27.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, “EPA Reaches $100 Million Agreement in Olympic – Shell Pipeline Case (Deal Includes $87 Million in State-of-the-art Pipeline Safety & Spill Prevention Work in Nine States), EPA.gov, December 11, 2002.

Daryl C. McClary, “Olympic Pipe Line Accident in Bellingham Kills Three Youths on June 10, 1999,” HistoryLink.org, June 11, 2003.

Associated Press, “Officials Sentenced in Pipeline Blast,” TDN.com/The Daily News Online, Longview, WA, June 19, 2003.

Carol M. Parker, “Pipeline Industry Meets Grief Unimaginable: Congress Reacts with the Pipeline Safety Improvement Act of 2002,” Natural Resources Journal, Winter 2004, Vol. 44, pp.243-282.

Emily Linroth, “Ten Years Later: Whatcom Creek Recovery,” WhatcomWatch.org, June 2009.

“How Bellingham’s Sunny June Day Turned into Fireball,” Bellingham Herald, June 7, 2009.

Kira Millage, “Timeline of Bellingham Pipeline Explosion,” Bellingham Herald, June 7, 2009.

“C-SPAN Cities Tour- Bellingham: The Olympic Pipeline Explosion,” YouTube.com, January 3, 2014 (overview of incident and subsequent regulatory changes, narrated on camera by Carl Weimer, Director of the Pipeline Safety Trust).

Jared Paben, “Whatcom, Hannah Creeks Heal With a Lot of Help After Pipeline Explosion,” Bellingham Herald, June 9, 2009; updated June 6, 2014.

Jim Thomson, Safety In Engineering Ltd., “Refineries and Associated Plant: Three Accident Case Studies,” SafetyInEngineering .com, 2013, 22pp.

Rebecca Craven, Program Director, Pipeline Safety Trust, “Pipeline Safety: Why Local Governments Should Care” (slide show w/ talk at NACO.org webinar), March 27, 2014.

“Whatcom Creek Pipeline Explosion: More Than a Decade of Healing,” Pipeline Safety Trust / PSTrust.org.

Andrew Restuccia and Elana Schor, “’Pipelines Blow up and People Die’. After a Series of Deadly Accidents, Congress Created an Office to Oversee the Nation’s Oil and Gas Pipelines. A Decade Later, It’s Become the Can’t-Do Agency,” Politico.com, April 21, 2015.

George Joseph, “30 Years of Oil and Gas Pipeline Accidents, Mapped. The Sheer Number of Incidents Involving America’s Fossil Fuel Infrastructure Suggests Environmental Concerns Should Go Beyond Standing Rock,” Bloomberg.com, November 30, 2016.

Tyler Kendig, “Pipeline Watchdog: Almost Two Decades after the Olympic Pipeline Explosion in Bellingham, Carl Weimer Continues the Fight to Improve National Pipeline Safety Standards,” ThePlanetMaga-zine.net, June 7, 2017.

Bellingham Herald, “Timeline of the 1999 Pipeline Explosion on Whatcom Creek,” YouTube.com, June 9, 2019.

Oliver Milman, “Washington State County Is First in U.S. to Ban New Fossil Fuel Infrastructure; Whatcom County’s Council Passed Measure That Bans New Refineries, Coal-fired Power Plants and Other Related Infrastructure,” TheGuardian.com, July 28, 2021.

Marianne Lavelle, “An Oil Industry Hub in Washington State Bans New Fossil Fuel Development. The Plan Brings Together Local Stakeholders, Including the Oil Industry, Labor Unions and Environmental Groups,” InsideClimateNews.org, July 29, 2021.

Ysabelle Kempe, “A Pipeline Exploded in Bellingham 22 Years Ago. It’s Still Influencing Federal Policy,” Bellingham Herald, August 22, 2021.

Jack Doyle, Crude Awakening: The Oil Mess in America, Friends of the Earth, Washington, D.C., 1993 (See Chapter 6, “A Crack in the Pipe,” with U.S. pipeline incident history & issues, most in the 1980s-early`90s, some 1960s &`70s). This chapter also included in submitted materials for the congressional hearing record at: ”Colonial Pipeline Rupture,” Before the Subcommittee on Investigations and Oversight of the Committee on Public Works and Transportation, House of Representatives, 103rd Congress, 1st Session, May 18, 1993.

National Wildlife Federation, “Full Oil Incident List: 2000-2010,” Jack Doyle research project for the National Wildlife Federation, Washington, D.C., June 2010.