Album and download art for "Link Wray, Rumble," used by Amazon, Apple and others. Click for Link Wray Collection.

The song’s offensive nature, apparently, had to do with the fear that it might incite gang violence. More on that in a moment. First, some context.

In the late 1950s, there were live dance nights held in Fredericksburg, Virginia hosted by the popular Washington, D.C. television disc jockey named Milt Grant — of Milt Grant’s House Party, a teen dance show similar to Dick Clark’s American Bandstand in Philadelphia. At one of these live dance events sometime in 1957, Link Wray and his band, a local group, were being urged to come up with a song like “The Stroll,” then a popular hit by The Diamonds. What Wray and his group came up with instead was an instrumental; a power-guitar driven, blues type song that would later become known as “Rumble.”

Old poster of Fredericksburg, VA arena, where Link Wray & band first performed an early version of the song “Rumble.”

However, when they tried to record it, they could not quite duplicate the sound they had on the dance night, especially frustrating Wray. That’s when he started moving speakers and mics around to get feedback, and then took a pencil and began punching holes through the speakers to get the sound he wanted. In a 1997 interview, Wray explained:

“…Onstage [at Fredricksburg], I’d been playing it real loud through these small, 60-watt Sears and Roebuck amplifiers, and the kids were hollering and screaming for it. But in the studio, the sound was too clean, too country. So I started experimenting, and I punched holes in the speakers with a pencil, trying to re-create that dirty, fuzzy sound I was getting onstage. And on the third take, there it was, just like magic.”

What Wray had done in his frustration was “invent” a new sound, a sound that would later become known as “fuzztone guitar.” There was also some novel use of reverberation on the track as well. Meanwhile, the song they had recorded on their demo was then using the name “Oddball.” And they began shopping it around to record labels, but there were no takers. Capitol and Decca Records both turned down “Oddball.”

Milt Grant then took the demo to Archie Bleyer of Cadence Records in New York. When Bleyer first heard the song, he hated it and the novel sound that Link Wray had created. Still, he recorded some demos, not sure what would happen next. Bleyer’s stepdaughter and some of her teenage friends, however, loved the song. One story has it that she was the one who suggested naming it “Rumble” because it reminded her of West Side Story, a popular stage play about rival New York street gangs. West Side Story had debuted on Broadway in 1957 and “rumble” was then the popular slang term for “gang fight.” Another account credits one of the Everly Brothers with coming up with the same name for the song. In any event, the tune became “Rumble” and Bleyer decided to release the song despite his dislike for it. Quoted in a promotional article in Billboard magazine at the time, Bleyer reportedly said something to the effect: “Rumble, schmumble, who cares, as long as it’s a hit?” “Rumble” was released on March 31, 1958 and began ascending the charts that summer — despite a bad rap. More on that in a moment.

Link Wray’s 1958 hit “Rumble” on the Cadence record label – a short lived venture for Wray, who would later move on to other record labels. Click for updated vinyl by Sundazed, NY.

Music Player

“Rumble”-1958

“Rumble” wasn’t exactly the lightest, easy listening fare of the day, true enough. Still, rock ‘n roll by then was finding its voice and raucuous edge. Although the term “rock and roll” dates to song lyrics from the 1920s and 1930s, a Cleveland disc jockey named Alan Freed in 1951 is credited with introducing the term to a much larger audience, especially through his play and promotion of African American rhythm & blues (R&B) music in the 1950s. New white artists, picking up on the R&B sound in some of their recordings, were also finding an audience. Bill Haley had “Rock Around the Clock” by mid-1955, and Elvis Presley had “Don’t Be Cruel” and “Hound Dog” by the fall of 1956. Both Haley and Presley had riled convention with their own rock ‘n roll styles. Still, rock ‘n roll music was by no means the dominant sound of the day. There was still plenty of more sedate, “easy listening” music to be found on the Billboard top twenty in the mid- and late-1950s — music from artists such as Andy Williams, Perry Como, Pat Boone, Tab Hunter, and others. “Rumble,” by comparison, was all instrumental, but a tune that had a distinct “attitude” about it. The guitar riffs in “Rumble” stood out, and went well beyond the moment. The musical sound created by Wray, and his distinctive playing, would soon have a direct effect on the future of rock and guitar music. “With one mean D-to-E chord change,” observes writer Angie Carlson in a 2007 Gibson.com article, “Link Wray changed the electric guitar forever.”

“Rumble” Not Played

But in the late 1950s, radio disc jockeys had the power of determining what music was played and what wasn’t. And in some cities and towns, including radio stations in Boston and New York City, “Rumble” just wasn’t played for fear it could incite gang violence or be an influence on juvenile delinquency. Even Dick Clark of American Bandstand was careful to avoid mention- ing the song’s title when introducing Wray on his Saturday show. The song’s title — “Rumble” — was a stumbling block for some DJs; they just couldn’t get past it. However, the song itself, an instrumental, had no lyrics of course, so there was no language per se to incite kids; no fiery rhetoric. Still, those aware of the controversy took precautions. Even Dick Clark of American Bandstand, the popular TV dance show, was careful to avoid mentioning the song’s title when he introduced Wray and his band as guests in May 1958.

Rock ‘n roll music was not always welcomed back then, and in fact, there were some efforts nationally to block the more objectionable sounds, suggestive lyrics, and loud or raucous music. Band leader Mitch Miller was one of those who helped put a damper on the more raucous forms of rock ‘n roll. Miller was then head of A&R — “artists and repertoire” — for Columbia Records, and as such, had the power to determine which musicians and songs would be recorded and promoted at Columbia and beyond. Miller had some of his own hit tunes on the Billboard charts of the 1950s. But he also had broad influence at the time, and was publicly critical of rock ‘n roll and Top 40 radio stations that played rock ‘n roll. Miller, however, did allow for some lighter forms rock ‘n roll, such as the 1957 million-selling hit by Marty Robbins, “A White Sport Coat and a Pink Carnation,” which he helped produce.

“Rumble” scene, 1957 stage production of “West Side Story” -- Jets leader vs. Sharks leader in knife fight. Click for film.

In addition, West Side Story’s gang scenes had permeated popular culture by 1957-58. In fact, a dance scene in Act 1 of the play is titled “The Rumble,” and other scenes also showed the activities of the play’s two featured gangs, the Jets and Sharks. “Juvenile delinquency” was a national topic of discussion by then as well, even attracting the attention of the U.S. Congress. There was also proposed legislation in Congress in 1957 that song lyrics be screened and altered by a review committee before being broadcast or offered for sale. That legislation, treading on free speech, never became law, but it was a sign of the times and part of the broader cultural concern then revolving around gangs and juvenile delinquency. In 1958 the Mutual Broadcasting System dropped all rock ‘n roll from its network music programs, calling it “distorted, monotonous, noisy music.” Link Wray’s instrumental was part of the music that became entangled in those fears and prohibitions.

Huge Hit

Nevertheless, despite all the tiptoeing around “Rumble” as a musical instigator of teen trouble, the song became a huge hit, rising to No. 16 in May 1958 and remaining in the Top 40 for 10 weeks. Despite Dick Clark’s care not to mention the song’s title at Wray’s earlier 1958 appearance, Bandstand did give the song enough air time to help it along, and Clark would freely use the song’s title in subsequent appearances by Wray in 1959 and 1963.

In fact, the attempted suppression of “Rumble” by some radio stations likely contributed to its success, as Wray himself would later surmise of the radio bans. “Rumble” went on to sell more than one million copies in its prime, with some estimates as high as four million, though it’s not clear what time frame is involved and whether sales of albums with the song are also included.

Link Wray, however, would not get a giant share of the royalties or music publishing fees from “Rumble.” Milt Grant, the DJ, was one co-author of the song, appearing on the Cadence label with “L. Wray.” But Link’s share, according to one account, appears to have been assigned to his father. Link would later say that he did receive enough money to buy his mother a house, but that he was generally spared the details of the “paperwork,” which appears to have kept his share lower than it might otherwise have been. He may have fared better with subsequent songs.

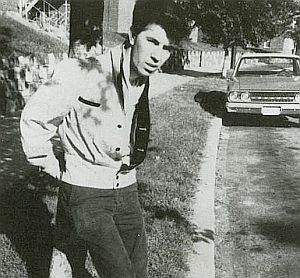

Photograph of Link Wray in his younger years, growing up. |

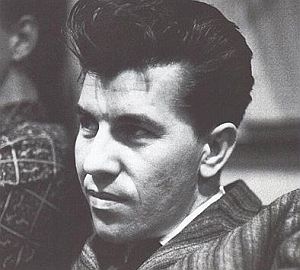

Link Wray, undated photograph. |

Meanwhile, back in the late 1950s, Archie Bleyer of Cadence Records — the guy who had first produced “Rumble” — was getting some external criticism for releasing the song. Bleyer was charged by some critics with “promoting teenage gang warfare.” Bleyer, nevertheless, thought he could “clean up” Link Wray and his group. Bleyer’s plan was to have the group record in Nashville, Tennessee under the guidance of the Everly Brothers’ production team.

But the Wrays didn’t like that idea, and decided to part company with Bleyer and Cadence Records. They soon joined Epic Records, recording a 1959 follow-up to “Rumble” called “Rawhide,” also an instrumental, which rose to No. 23 on the pop charts. In subsequent years, the group also had other notable songs, including “Jack the Ripper” (1961), “Black Widow” (1963), “Big City After Dark” “Run Chicken Run” (1963), “Ace of Spades” (1965), “Switchblade,” and “Red Hot (1977). Thereafter, Link Wray would not hit the pop charts in quite the same way again, but would have influence in other ways.

Part Shawnee

Fred Lincoln Wray was born in Dunn, North Carolina in 1929. According to some accounts his parents were semi-literate and engaged in street preaching from time to time. Wray was also reported to be part Shawnee Indian. He is quoted in one Associated Press story of 2002 saying:

“I’m half Shawnee Indian, born to a Shawnee mother. I had a Shawnee dad, and he was in the First World War…and he was shell-shocked…. I had to go to work when I was 10 years old to help feed the family. This was Dunn, North Carolina, in a different era, you know, during the Ku Klux Klan days, you know…really bad in the South.”

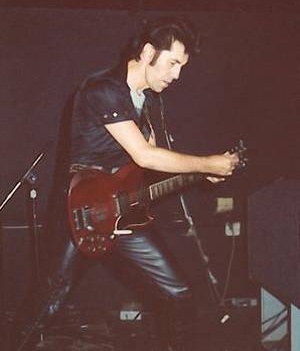

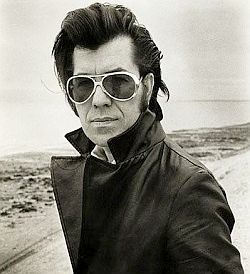

Link Wray performing later in his career. |

Wray explained that he shook with fear at the KKK raids. In Dunn, they lived in a black neighborhood. “I seen the sheets come,” Wray would recount in another interview, referring to the KKK, “pull out the black people, tie ’em to a tree, and beat…’em. We’d hide underneath the bed, hopin’ they wouldn’t come for us.”

For a time, Wray’s family slept on the floors of barns under the protection of Cherokees and ate whatever they could find. “Elvis, he grew up — I don’t want to sound racist when I say this — he grew up white-man poor,” said Wray, comparing his experience to that of Elvis Presley. “I was growing up Shawnee poor.” An early bout with the German measels had also left Wray with weak eyesight and hearing.

When Wray was about age 8, a traveling black guitarist and sometime circus performer named Hambone introduced him to the blues, giving him guitar lessons on his front porch, and showing the young boy a few chords and how to play slide guitar. Wray’s father later worked in the dockyards of Portsmouth, Virginia, and the family moved there from North Carlina, which for young Link was a welcomed development.

“It was like moving from one world to a whole ‘nother,” he would tell one reporter years later. “I couldn’t believe it — all of the sudden I could turn on a stove and it was gas fire, I could turn on a switch and it was electricity.”

In 1951, Wray was drafted into the U.S. Army, sent to Germany and Korea, where he contracted tuberculosis, which later led to the removal of his left lung. But when he first returned to the U.S. in 1953 after his Army hitch, he ordered a Gibson Les Paul guitar. It was then he developed his own style, playing louder, in part, because of his bad hearing.

By 1955 Wray started playing as a member of Lucky Wray & the Palomino Ranch Hands, a country music band formed in North Carolina with his brothers Vernon and Doug, and later one other member. The Wray brothers soon moved to just outside of Washington, D.C., and recorded some songs on a local label named Kay and also for Starday Records in Texas. By 1958, Link Wray’s brother was doing the vocals in the band, while Link focused on the guitar. Cast a bit in the “Elvis look” of that era, the band dressed in black leather and began playing the local record hops.“…[A]ll of a sudden” in the 1950s, this guy in a black leather jacket “plays this loud chord that practically tears your eyebrows off your face…”

– Michael Molenda

Guitar Player magazine Wray became inventive in a hunt for his “own sound,” such as poking holes in an amplifier to get the sound he wanted in “Rumble.” He was also one of the first guitarists to take a major chord and run it up and down the fret board, creating the sound known as the power chord.

Music historians of the late-1950s-early1960s era would observe some years later that there probably was a bit of “juvenile attitude” in Wray’s “Rumble.” Dan Del Fiorentino, historian for the Museum of Making Music in Carlsbad, California told the Los Angeles Times in a 2005 interview that “Rumble” added “more of a zing, more of a delinquency, if you will, to rock ‘n’ roll.” Michael Molenda, editor-in-chief of Guitar Player magazine, also noted in the same article: “Fifties rock was pretty clean, and you’ve got this guy — he’s got a leather jacket, he looks scary — and all of a sudden he plays this loud chord that practically tears your eyebrows off your face…It was extremely sexy and aggressive, and it kind of paved the way for the next level of rock and roll.” Without the power chord that Wray more or less invented with “Rumble,” explains Dan Del Fiorentino, “punk rock and heavy metal would not exist.” And Wray is revered by a number of the most famous guitar-wielding rockers. Jimmy Page of Led Zeppelin, Bruce Springsteen, and Jeff Beck all count Link Wray as an influence in their own careers. Bob Dylan is reported to have called “Rumble” one of the best instrumentals ever.

In June 2009, the Library of Congress announced that “Rumble” would be among selections added to the National Recording Registry for 2008 – an honor for recordings “that are culturally, historically or aesthetically significant.”An accompanying essay on Wray and “Rumble’s” selection noted: “…He has been called the ‘missing link’ in rock guitar, the connecting force between the early blues guitarists and the later guitar gods of the 1960s (Hendrix, Clapton, Page). He’s the father of distortion and fuzz, the originator of the power chord and the godfather of metal…” In January 2019, Wray’s ‘Rumble” was also inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame.

In April 2018 at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, Link Wray’s “Rumble” was among six songs honored in a new category of recognition: singles by artists not yet inducted into the Hall, but have helped shape rock `n roll in some way. “Rumble” is distinguished for Wray’s founding of the power chord and his use of guitar distortion. Hall of Famer Stevie Van Zandt of the E-Street Band, who introduced the new category of honored songs, has stated elsewhere about Wray and “Rumble”:

…That “Rumble” riff by Link Wray, who is really the founder of the hard rock riff… He introduced the seven chord, which I don’t want to get too technical, but it’s the chord that “You Really Got Me” [Kinks song] is based on; The Who’s “My Generation” is based on. That chord change – what we call the one-seven chord change – it’s in the riff. That’s what gives it that attitude; that attitude is immediately there in the first five seconds of the song. That attitude comes from that particular melody on that chord change. It’s the sexiest, toughest chord change in all of rock `n roll.

By the early 1970s, a few of Link Wray’s songs were finding their way into other venues. Wray’s “The Swag” was used in the 1972 film, Pink Flamingos. “Jack the Ripper,” another of his instrumentals, was used as the music behind a high-speed car chase in the 1983 film, Breathless, with Richard Gere and Valérie Kaprisky.

In Quentin Tarantino’s 1994 film, Pulp Fiction, both “Rumble” and “Ace of Spades” were used. In the 1995 film, Desperado with Salma Hayek and Antonio Banderas, “Jack The Ripper” was used. In 1996, Independence Day, the highest grossing film that year, Wray’s “Rumble” made another appearance.

“Rumble” was also used in the January 1999 pilot episode of HBO’s The Sopranos. A first use of Wray’s music in TV advertising also came in 1999 with excerpts of “Jack the Ripper” used in a Taco Bell commercial.

In 2001, “Rumble” was used in the film Blow, starring Johnny Depp and Penélope Cruz. “Rumble” was also used in 2009’s It Might Get Loud, a documentary on the history of the electric guitar by film-maker Davis Guggenheim. These film uses of Wray’s music brought the Link Wray sound to a new audience, gave it another shot in the market and renewed appreciation by fans and other artists.

Over the years, there have also been various cover versions of Wray’s songs in new music, such as the song “Killer in the Home” (based on “Rumble”) by New Wave group, Adam and the Ants, included on their Kings of the Wild Frontier album of 1980. The guitarist for this group, Marco Pirroni, has cited Link Wray as a major influence.

Wray’s legacy is found not only in the U.S., but also in Great Britain, where his music has been cited as an influence on The Kinks and The Who, among others. Pete Townshend of The Who has stated that “if it hadn’t been for Link Wray and ‘Rumble,’ I would have never picked up a guitar.” Townshend also said of his first impression on hearing the song: “…Link Wray never toned the music down. He was always ready to Rumble…”

– Richard Harrington

Washington Post “I remember being made very uneasy the first time I heard it, and yet excited by the savage guitar sounds.” Ray Davies of The Kinks also cites Wray as an influence. In 2003, Rolling Stone’s entry for Wray in their “100 Most Important Guitarists in History,” called him the man behind “the most important D chord in history.” Wray was ranked at No. 67 on that list. The Rolling Stone entry also credits Wray with creating “the overdriven rock-guitar sound taken up by Townshend, Hendrix, and others.”

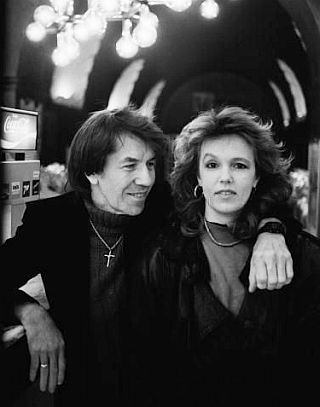

1996. Link Wray and his wife Olive, in Copenhagen, Denmark.

Link Wray continued performing his music into his 70s. “He just loved playing,” said Michael Molenda, editor-in-chief of Guitar Player magazine, who had seen Wray perform in 2005 in San Francisco. “He wasn’t like a guy who was 76 years old,” Molenda told the Los Angeles Times. “He was like a 19-year-old in a 76-year-old body.”

Wray lived his last years with his wife Olive on a Danish island. He died of heart failure in Copenhagen in early November 2005. “Link Wray never toned the music down,” wrote Richard Harrington of the Washington Post at Wray’s death. “He was always ready to Rumble.”

See also at this website, “Pop Music, 1950s,” a topics page offering links to more than a dozen stories on music and artists from the 1950s. For additional stories on music history, artist biographies, and song profiles see the “Annals of Music” category page. Thanks for visiting – and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research and writing at this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

_____________________________

Date Posted: 10 May 2010

Last Update: 10 August 2019

Comments to: jdoyle@pophistorydig.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Rumble Riles Censors, 1958-59,”

PopHistoryDig.com, May 10, 2010.

________________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

Link Wray photo, by San Francisco photographer, Bruce Steinberg. |

Spencer Leigh, “Link Wray Obit,” RockabillyHall .com.

Cain Burdeau, Associated Press, “The Original Man in Black: Link Wray Still Rumbles,” August, 2002, RockabillyHall .com.

Lawrence Laurent, “10- Count ‘Em- 10 Top- notchers Has Milt,” The Washington Post-Times Herald, April 10, 1958, p. C-14.

“Milt Grant Plugs A Hit – His Own,” The Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), June 1, 1958.

Frank Simpson, “Link Wray Opened Up The Guitar to Distortion…And Pete Townshend Listened,” Hit Parader (music magazine), 1971.

Angie Carlson, “How a One-Lunged Shawnee Indian Invented Punk: Link Wray, ‘Rumble’ and the Meanest D Chord Ever,” Gibson.com, December 14, 2007.

Richard Harrington, “Prophet of the Rock Guitar: With Pick and Pencil, Link Wray Pointed the Way,” Washington Post, Tuesday, November 22, 2005.

Dennis McLellan, Obituaries, “Link Wray, 76; Rebel Guitarist’s Power Chord in ‘Rumble’ Started Rock Music on Its Journey to Punk and Heavy Metal,” Los Angeles Times, November 22, 2005, p. B-8.

“Link Wray,” and “Rumble,” Wikipedia.org.

“1958-1959, USA, Link Wray,” History of Music Censorship,” FreeMuse.org.

Source for West Side Story “Rumble” photo, 1957 stage production.

Fred Bronson, “A Selected Chronology of Musical Controversy,” Billboard, March 26, 1994, p. N-36.

Detailed Link Wray website, WraysShack3 Tracks.com.

Jimmy McDonough tribute story, “Be Wild, Not Evil: The Link Wray Story,” Perfect Sound Forever, Online Music Magazine, 2006.

Link Wray Appearance on The Jack Spector Show, Channel 12 WPRO-TV, Providence, RI, performing, “Trail Of The Lonesome Pine,” March 1960.

Link Wray Album/CD list, Aykw.com.

Museum of Making Music, Carlsbad, California.

“Link Wray In By A Song; Rock Hall Honors ‘Rumble’,” ElmoreMagazine.com, April 16th, 2018.

“Rumble Web Exclusive: Stevie Van Zandt on Link Wray’s Hard Rock Riff,” YouTube.com, August 3, 2017.

“RUMBLE: The Indians Who Rocked the World” (Official Trailer), YouTube.com, April 28, 2017.

U.S. Library of Congress, Press Release, “The Sounds of American Life and Legend Are Tapped for the Seventh Annual National Recording Registry” (Link Wray and “Rumble” included for 2008), LOC.gov, June 9, 2009.

Cary O’Dell essay at, “Rumble—Link Wray (1958),” National Registry: 2008, LOC.gov.

Jack Doyle, Email correspondence with Elizabeth Wray Webb, August 2019.

Richard Harrington, “Wray’s ‘Rumble’ Still Reverberating,” Washington Post, January 13, 2006.

___________________________________