An estimated 30 million Americans watched the 'Kefauver hearings' in 1950-51, some in movie theaters like this one. (Photo - M. Rougier/Life).

Beginning in Washington, D.C. in May of 1950, the Kefauver hearings lasted 15 months with sessions held in 14 cities. More than 600 witnesses gave testimony. The Kefauver Hearings were not the first congressional hearings to be televised, but they did mark the first time that a large national audience became involved in a public policy matter by way of television.

Although fewer than half of all American homes had TV sets in 1950-51, many were able to watch in bars, restaurants, and businesses. Some movie theaters also ran the hearings, as shown in the photo at right.

'Crime Hunter Kefauver'-Time cover, 12 March 1951.

“Best Show in Town”

The Kefauver hearings on organized crime proved a fascinating and engrossing revelation to many Americans — introducing for the first time to many viewers terms such as “the Mafia” and the details of how criminal organizations worked. During eight days of hearings in New York City in mid-March 1951, for example, over 50 witnesses described the highest-ranking crime syndicate in America — an organization allegedly led by Frank Costello who had taken over from Lucky Luciano. According to Life magazine, “the week of March 12, 1951, will occupy a special place in history. . . people had suddenly gone indoors into living rooms, taverns, and clubrooms, auditoriums and back-offices. There, in eerie half-light, looking at millions of small frosty screens, people sat as if charmed. Never before had the attention of the nation been riveted so completely on a single matter.”

The Kefauver hearings also had the advantage of being the “best show” in town at the time — and for the most part, the only show in terms of available daytime content. The witnesses, testimony, and interrogation-by-senators offered compelling programming for TV networks then trying to fill up their telecasts. “…Dishes stood in sinks, babies went unfed, busi- ness sagged, and depart- ment stores emptied while the hearings were on.”

—Time magazine

Television was still new then, and daytime television was wide open. Prime-time slots were filling up, but daytime needed programming, and the Kefauver hearings fit the bill nicely. Advertisers then could have big chunks of daytime TV fairly cheaply Time magazine, for example, helped sponsor the Kefauver hearings in New York and Washington, promoting magazine subscriptions in its advertising. The TV networks were just beginning operations in some cases, so experience was thin, and broadcast range limited. The New York sessions of the Kefauver hearings, for example, went out live over a “national” network that included twenty cities in the East and the Midwest. Still, in some cities at that time, the purchase of television sets had begun to skyrocket, and the Kefauver “show” no doubt helped push sales along too. In the New York city area, the number of sets had doubled in the 1950-1951 period.

April 7, 1951 edition of "The Saturday Evening Post" headlines a story about the Kefauver Hearings.

Once the hearings began, they became something of a national event, with TV providing the new means for connecting millions of onlookers all at once. And throughout the country, people began tuning in. Housewives, in particular, who were more at home in those days than they are today, called their friends to spread the word about the new show.

“From Manhattan as far west as the coaxial cable ran,” wrote Time magazine, “the U.S. adjusted itself to Kefauver’s schedule. Dishes stood in sinks, babies went unfed, business sagged and department stores emptied while the hearings were on.” The drama was real life: crime bosses, street thugs, and U.S. Senators; good guys vs. bad guys.

“Estes Kefauver came off as a sort of Southern Jimmy Stewart, the lone citizen-politician who gets tired of the abuse of government and goes off on his own to do something about it,” wrote David Halberstam in his book, The Fifties.

National Celebrity

In the end, Kefauver’s crime hearings attracted an estimated 20-30 million television viewers. However, the hearings didn’t always play well in every city, such as Las Vegas, nor have a positive or lasting result (see sidebar below). But they did make Estes Kefauver a national political celebrity, establishing him in the public mind as a crusading crime-buster and opponent of political corruption.

Before long, he was on the lecture circuit, appearing in magazines, and also on television shows like What’s My Line? At one point, Hollywood even called him to play bit part in a Humphrey Bogart movie called The Enforcer.

In the Saturday Evening Post, a ghostwritten four-part series about his investigation titled “What I Found in the Underworld” was published under his name in the Spring of 1951.

A subsequent book by Keafauver, Crime in America, written with Sidney Shalett, was on The New York Times best-seller list for twelve weeks.

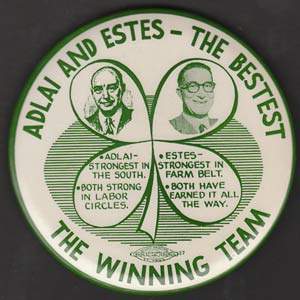

1952 Kefauver button.

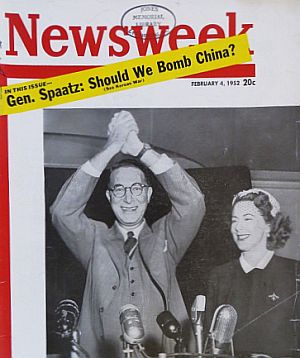

As a result of all the national exposure, Kefauver’s political fortunes rose precipitously, and in 1952 he sought the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination. He made history briefly when he defeated President Harry S. Truman in the New Hampshire primary, proceeding to win twelve of the fifteen Democratic primaries. But the primaries at that time were not the main method of delegate selection. At the national convention in Chicago that summer, Kefauver led on the first two convention ballots. But in the end Adlai Stevenson received the Democratic nomination. In the general election, Stevenson and running mate Senator John Sparkman of Alabama lost to the Republican ticket of Dwight D. Eisenhower and Richard M. Nixon. Estes Kefauver, however, would be back.

|

“Kefauver in Las Vegas” The producers of the PBS documentary film, Las Vegas: An Unconventional History, covered Kefauver’s hearings in their film, and posted some interesting observations on their web site. An excerpt follows here: . . . On November 15, 1950, Kefauver and his colleagues arrived in Las Vegas. The committee had already been conducting hearings for five months, and they were tired. Many of the high profile casino owners who had received subpoenas for the committee, like Moe Dalitz, had skipped town. Kefauver and his committee interviewed only six witnesses, and these were hardly helpful. It was the same throughout the hearings; ambiguous answers and flat-out denials were the norm. After just two hours of interviewing witnesses, the committee took a break to visit Boulder Dam. Upon returning, they continued the hearings for a short time before holding a press conference and calling the Las Vegas portion of the investigation to an end. All told, the hearings barely lasted a day. To Las Vegans, the hearings were both a relief and almost disappointingly anti-climactic. As a story covering the hearings in the Las Vegas Review-Journal began, “The United States Senate’s crime investigating committee blew into town yesterday like a desert whirlwind, and after stirring up a lot of dust, it vanished, leaving only the rustling among prominent local citizens as evidence that it had paid its much publicized visit here.” What Kefauver and his colleagues were finding was that the relationship between politicians, authorities and mobsters was not as clear-cut as had been posited. . . . .Syndicate members were often major donors to political campaigns. Many prominent politicians of the day, even those who publicly praised Kefauver’s efforts, had intimate, albeit secret, ties with Syndicate members. Kefauver himself was known to be fond of gambling, and committee member Herbert O’Conor was rumored to have ties to the Mafia. The Kefauver Committee’s final report was more than 11,000 pages long, out of which only four pages pertained to Las Vegas. [T]he committee came up with little new information about Las Vegas . . . . To remedy Las Vegas’ apparent inability to keep organized crime out of city lines, Kefauver suggested that the federal government impose a 10 percent tax on all gaming. But such a proposition would have been disastrous for Las Vegas, and Senator Pat McCarran fervently and successfully argued against Kefauver’s suggestion. . . .Nevada officials were eventually pressured to make steps toward some kind of gaming oversight. In 1955, to weed out gangsters, the state required that any owner of a casino be licensed by the state gaming board. The act inadvertently enshrined organized crime. It ruled out corporations, which have thousands of shareholder “owners,” making personal (and mostly illegal) fortunes the only money readily available. That was Kefauver’s legacy. Later, Nevada created the Gaming Control Board, and adapted more stringent laws in an attempt to weed out gangster applicants for licenses. In 1960, the Gaming Control Board published “the Black Book,” officially entitled A List of Excluded Persons, banning known gangsters from casinos. . . .While the Kefauver hearings did bring the problem of organized crime to the national consciousness, forcing the FBI and the government to publicly admit that such an organization existed, the hearings did relatively little to damage the strength of the Syndicate. In fact, the hearings persuaded local hoods that they were free from the law — a Senate committee had come to town and nothing happened. The presence of organized crime grew even stronger and more concentrated in Las Vegas, as another wave of criminals, seeking refuge after being run out of their home states, surged into Nevada. The Syndicate would continue to wield control of Las Vegas for two decades after the conclusion of the Kefauver Hearings. Source: PBS Television, The American Experience, Las Vegas: An Unconventional History. |

Senator Estes Kefauver with wife, shown on the cover of Newsweek, February 4, 1952, announcing presidential bid.

Kefauver had grown up in the small town of Madisonville, Tennessee in the foothills of the Great Smokies. His father owned a hardware store there and had served as the town’s mayor. Growing up, young “Keef” as he was nicknamed, worked one summer in a Harlan County, Kentucky coal mine living with four other miners and developing an abiding appreciation for coal mine life and labor unions.

At the University of Tennessee Kefauver was a fraternity man, who threw discus and high-jumped on the track team, played tackle on the varsity football squad, and was elected president of the student body. After graduating in 1924, he taught math and coached high school football for a year, then went to Yale Law School.

In the courtroom, he was good with juries, and according to one of his former partners, used the “country boy” approach to good effect. But as a lawyer, Kefauver also used plain language and a straight-forward approach jurors could understand, and he never tried to be eloquent or poetic. In 1938, he made an unsuccessful bid for the state senate, then won a U.S. congressional vacancy the following year. In nine years in the U.S. House of Representatives, Kefauver championed public power programs of the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) and New Deal programs.

In 1947, when he ran for a U.S. Senate seat, he traded country quips and raccoon stories with his opponent. That resulted in one instance with Kefauver donning a coonskin cap which then became something of a campaign trademark for him. He was later shown wearing one on the March 1952 cover of Time magazine (coincidentally, after Walt Disney ran a TV series on Davy Crockett, who also wore the coonskin cap, a “Crockett craze” ensued in 1955 with young boys all across the country wearing the caps). Kefauver won his U.S. Senate seat in the 1948 election, and following his rise in national notice with the crime hearings described above, sought the presidency for the first time in 1952.

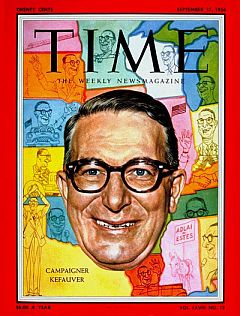

Time cover in Sept 1956 as the Stevenson-Kefauver ticket sought the White House.

2nd Presidential Bid

In 1956, Kefauver again sought the Democratic Party presidential nomination, scoring a few upsets and winning some important primaries, until losing a key battle in California. At the convention, the nomination was thrown open to the delegates but Adlai Stevenson was again selected the party’s nominee. However, Kefauver did win the Vice Presidential slot in a competition with a young U.S. Senator from Massachusetts named John F. Kennedy. The Stevenson-Kefauver ticket lost to the Eisenhower-Nixon ticket in 1956, and Kefauver returned to his Senate post. (Kefauver was considered the front runner for the 1960 Democratic nomination, but he let it be known in 1959 that he wasn’t going to try again for a third time.)

Senate Career

In the Senate, Kefauver turned his attention to big business and monopoly practices. His U.S. Senate Antitrust and Monopoly Subcommittee investigated economic concentration throughout the U.S. economy, industry by industry, issuing a major report in May 1963. He found monopoly pricing in the steel, automotive, In 1956, Kefauver was one of 3 southern Democrats in the Senate who refused to sign the “Southern Manifesto.” food and pharmaceutical industries, and recommended among other things, that General Motors be broken up into competing firms. He was also highly critical of excess profits in the U.S. drug industry. The Kefauver-Harris Drug Control Act of 1962 required drug companies to disclose to doctors the side-effects of their products, be able to prove their products were effective and safe, and allow drugs to be sold as generics. In 1956, Kefauver and fellow Tennessee Senator Albert Gore Sr., and Lyndon Johnson were the only three southern Democrats who refused to sign the “Southern Manifesto,” a political document signed by more than 90 other politicians opposing racial integration. On August 8, 1963, Estes Kefauver suffered a massive heart attack on the floor of the Senate, and died a few days later.

For additional stories on politics at this website please see the “Politics & Culture” category page. Stories from the 1950s and 1960s are also grouped by decade in the “Period Archive,” found at the top right corner of this page. Thanks for visiting – and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research and writing at this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

_____________________________

Date Posted: 17 April 2008

Last Update: 20 January 2020

Comments to: jdoyle@pophistorydig.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “The Kefauver Hearings, 1950-1951,”

PopHistoryDig.com, April 17, 2008.

_____________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

1956: Adlai Stevenson and Estes Kefauver. |

1956: Stevenson-Kefauver button for the 1956 Presidential campaign. |

“It Pays to Organize,” Time (cover story), Monday, March 12, 1951.

“The Rise of Senator Legend,” Time (cover story), Monday, March 24, 1952.

Joseph Bruce Gorman, Kefauver: A Political Biography, New York: Oxford University Press,1971.

David Halberstam, The Fifties, New York: Villard Books/Random House, 1993, Chapter 14, pp. 187-194.

See an extensive collection of photographs of the Kefauver Crime Hearings in Kansas City, Missouri, at the Western Historical Manuscript Collection Photo Database, 222 Thomas Jefferson Library, One University Blvd. University of Missouri, St. Louis, MO (314) 516-5143.

G. D. Wiebe, “Responses to the Televised Kefauver Hearings: Some Social Psychological Implica- tions,” The Public Opinion Quarterly, Vol. 16, No. 2, Summer, 1952, pp. 179-200.

Estes Kefauver & Kefauver Hearings, People & Events, “Las Vegas: An Unconventional History,” The American Experience, Public Broadcasting System (PBS) Television, 2005.

U.S. Senate, “May 3, 1950: Kefauver Crime Committee Launched,” Historical Minute Essays, 1941-1963.

Jack Anderson and Frederick G. Blumenthal. The Kefauver Story, New York: Dial Press, 1956.

Ivan Doig, “Kefauver Versus Crime: Television Boosts a Senator,”Journalism Quarterly, Autumn 1962, pp. 483-90.

U.S. Congress, Memorial Services Held in the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States, Together with Remarks Presented in Eulogy of Carey Estes Kefauver, Late a Senator from Tennessee, 88th Congress, 1st session, 1963. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1964.

Estes Kefauver, with Irene Till, In a Few Hands: Monopoly Power in America, New York: Pantheon Books, 1965.

Joseph Bruce Gorman, “The Early Career of Estes Kefauver,” East Tennessee Historical Society’s Publications, 1970, pp. 57-84.

Philip A. Grant, Jr., “Kefauver and the New Hampshire Presidential Primary,”Tennessee Historical Quarterly, Winter 1972, pp. 372-80.

Harvey Swados, Standing Up for the People: The Life and Work of Estes Kefauver, New York: E.P. Dutton, 1972.

Richard Edward McFadyen, Estes Kefauver and the Drug Industry, Ph.D. dissertation, Emory University, 1973.

William Howard Moore, The Kefauver Committee and the Politics of Crime, 1950-1952, Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1974.

James Bailey Gardner, “Political Leadership in a Period of Transition: Frank G. Clement, Albert Gore, Estes Kefauver, and Tennessee Politics, 1948-1956,” Ph.D. dissertation, Vanderbilt University, 1978.

Richard Edward McFadyen,”Estes Kefauver and the Tradition of Southern Progressivism,” Tennessee Historical Quarterly, Winter 1978, pp. 430-43.

William Howard Moore, “The Kefauver Committee and Organized Crime,”in, Law and Order in American History, Joseph M. Hawes (ed.), Port Washington, NY: Kennikat Press, 1979, pp. 136-47.

Charles L. Fontenay, Estes Kefauver, A Biography, Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1980.

William Howard Moore,”Was Estes Kefauver ‘Blackmailed’ During the Chicago Crime Hearings?: A Historian’s Perspective,” Public Historian, Winter 1982, pp. 5-28.

Philip A. Grant, Jr., “Senator Estes Kefauver and the 1956 Minnesota Presidential Primary.” Tennessee Historical Quarterly, Winter 1983, pp. 383-92.

Gregory C. Lisby, “Early Television on Public Watch: Kefauver and His Crime Investigation,” Journalism Quarterly, Summer 1985, pp. 236-42.

Jeanine Derr, ” ‘The Biggest Show on Earth’: The Kefauver Crime Committee Hearings.” Maryland Historian, Fall/Winter, 1986, pp. 19-37.

Hugh Brogan, All Honorable Men: Huey Long, Robert Moses, Estes Kefauver, Richard J. Daley, New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Film Clips of the Kefauver Hearings. See, for example, eFootage.com, where the following clips are available: 1.) Morris Kleinman “The Silent Witness” – Cleveland Gambler, Morris Kleinman, remains silent during his questioning at the Kefauver Crime Committee hearing in Washington and then he gets reprimanded by one of the Senators; 2.) Abner “Longy” Zwillman – Abner “Longy” Zwillman on trial during the Kefauver Crime Committee hearing in Washington. The organizer and the founding member of a nationwide crime syndicate talks about his reputation as the “Al Capone of New Jersey” and getting in too deep with the mob; 3.) Senators & Abner Zwillman – The senators involved in the Kefauver Hearings and the notorious gangster Abner “Longy” Zwillman being questioned; 4.) James J. Carroll’s “Fright Factor” – St Louis’ Betting Commissioner James J. Carroll at the Kefauver Crime Committee hearing voicing his opinion that the media presence in the courtroom is a “fright factor” and claiming that he doesn’t know whether he can answer the questions properly with all the cameras present; 5.) James J Carroll Talking – St Louis’ Betting Commissioner at a Kefauver Crime Committee in Washington, denying that he’s ever known a man named Frank Costello or Nicki Cohen; 6.) Jacob “Greasy Thumb” Guzik – Jacob Guzik, one of the heads of the Chicago underworld, at the Kefauver Crime Committee hearing; and 7.) A Crowded Kefauver Committee Hearing – The Kefauver Crime Committee hearing played to a standing room only crowd in Washington, D.C. and were filmed by several news crews.