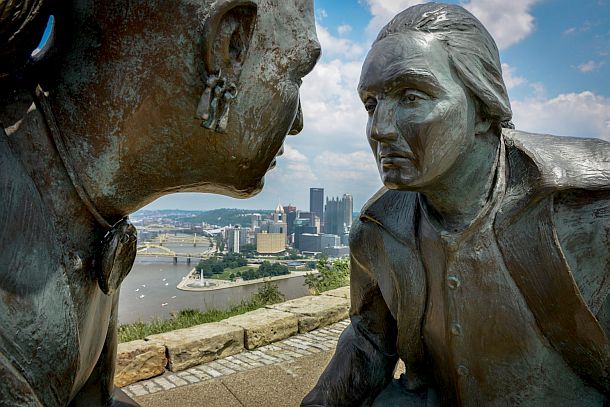

The sculpture shown below – overlooking present-day Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania – captures an October 1770 campfire meeting between a young George Washington of colonial Virginia and a Native American leader named Guyasuta. Among other things, the two men, from vastly different cultures, were talking about the fate of the region’s land, both at Pittsburgh and what would become Western Pennsylvania and beyond. At the time, this region was the western edge of the North American colonies of Great Britain, essentially wilderness and a crossroads to an assortment of adventurers, militia men, traders, missionaries, slaves, and settlers. According to local historians, there were fewer than 200 whites living at the “forks of the Ohio River,” i.e., Pittsburgh at the junction of the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers. It was there that former frontier forts would be built – first, Ft. Duquesne for the French, followed by Ft. Pitt under the British. The French, British, native Americans, and American colonists would all do battle in the region. And it was in that context – during the 1750s-1770s – that Washington and Guyasuta would come to know one another.

The bronze sculpture, “Point of View,” of Seneca leader Guyasuta meeting George Washington in 1770, overlooks Pittsburgh, PA. It was installed in 2006. Sculptor, James West. (photo, Jim Judkis/Washington Post).

Born in 1724, Guyasuta or Kiasutha (one of several historical spellings), was a member of the Seneca-Mingo tribe, one of six that made up the Iroquois Nation. Originally from Western New York, Guyasuta’s branch of the Seneca had migrated down the Allegheny River some decades earlier and settled in the Western Pennsylvania area and nearby “Ohio Country.” Early maps of the region, as the one below, show this area as being essentially Indian country.

18th century map of some of the early British Colonies, showing the dark mustard-colored area (at left) with various forts in what is today Western Pennsylvania, then a frontier region populated by indigenous American Indians.

The British, French, and private interests all had designs on this region from the 1740s on. A British land company named The Ohio Company, was one of the private ventures – with George Washington’s father, Augustine, among its investors. The Ohio Co. was given 500,000 acres of British land grants in 1749 in the area between the Kanawha River and the Monongahela – 200,000 acres initially, and an additional 300,000 with the successful settlement of 100 families within seven years. Land grants, land ownership, and land speculation were foreign concepts to Native Americans, who generally regarded land as a shared commons. The British and the French both wanted the region, with “the forks” location being particularly strategic for river travel inland and beyond. The British and French, in various alliances with Native Americans, would soon go to war over the region. In any case, what would become Western Pennsylvania and part of Ohio would be in flux and conflict from the 1740s through the early 1800s. It was in this context of the region’s early contested settlement and wider Colonial wars that Guyasuta and Washington would come to know each other.

Early artist’s depiction showing Native Americans overlooking “the forks” area with fortification that would become modern-day Pittsburgh, with the Monongahela River in foreground and Allegheny River beyond (together forming at far left, but not shown, the Ohio River). This painting captures the region’s rugged wilderness character at about the 1750s.

George Washington was born into the landed gentry of Virginia in 1732. He grew up in Mount Vernon, Virginia. In 1749, at the age 17, he was appointed official surveyor for Culpeper County, Virginia, a well-paid position which enabled him to begin purchasing land in Virginia. By 1753, Washington had also been appointed to the rank of major in the Virginia militia by Virginia‘s governor. In that year, Guyasuta and Washington would meet for the first time, as Washington made his first visit to the rough frontier country of Western Pennsylvania. The French at the time – who had worked in the area for some years and built forts there – were trying to establish more permanent roots in the “Ohio Country” region, which the British then claimed for the Virginia and Pennsylvania colonies.

Statue at Waterford, PA depicting George Washington delivering letter to the French at Fort Le Boeuf. |

George Washington, then 21, was given orders by lieutenant governor of Virginia, Robert Dinwiddie, to undertake a diplomatic expedition to the region with a message for the French commandant of Fort Le Boeuf, a French outpost south of Lake Erie (now Waterford). Washington’s mission was to convince the French to abandon the string of forts they had constructed between Erie and Pittsburgh.

On his journey, Washington arrived at Logstown, a native American trading village. There, he was introduced to various local leaders and Indian chiefs, including Guyasuta. The Seneca chief, who would later use “Tall Hunter” as the name to describe the six-foot Washington, was recruited to help guide Washington and his party to Fort Le Boeuf.

Guyasuta appears to have helped guide Washington along the Allegheny River portion of his journey. Other Iroquois were also assisting, according to some accounts, but it is not clear if Guyasuta stayed with the party for the entire trip.

However, Washington’s mission to persuade the French to leave the region failed, and within a year, the French and Indian War had begun – so named as the Indians sided with the French against the British and the colonists.

On making the return trip from Fort Le Boeuf, Washington and his guide, Christopher Gist, nearly died that winter when their raft broke apart attempting to cross the icy Allegheny River – this according to excerpts from Washington’s own journal.

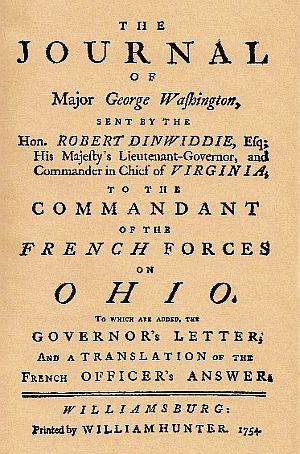

In fact, Washington’s journal was such good frontier reading for the times that Virginia’s Governor Dinwiddie had it published both in Williamsburg, Virginia and in London, England. Washington’s published account was widely read, and his engaging tales of travel, diplomacy and adventure helped advance his career as an up-and-coming political leader. The book also elevated Washington as one of the country’s first frontier heroes. One of those who read and commented on Washington’s published account was none other than Britain’s King George II.

Washington’s journal also turned out to be of strategic importance to the British, as it included a map that illustrated the extent of the French threat and holdings in the Ohio Valley. It also contained one of the first references to the construction of a French fort at the junction of the Monongahela and Allegheny rivers, the site of present-day Pittsburgh. And as the French and Indian War commenced, Washington would also become involved in the military action, participating in an ambush of a French detachment in 1754.

Guyasuta With French

Guyasuta sided with the French in the war, and he and Washington would soon fight on opposite sides. In 1755, the British sent the Braddock Expedition with colonial troops under the command of Gen. Edward Braddock into the region. Major George Washington was part of that expedition. They were heading to do battle with the French and Indian forces at Fort Duquesne, located at the forks of the Ohio.

En route, the colonial and British troops under Braddock were surprised and soundly defeated by French and Indian forces from Ft. Duquesne who had learned they were coming. Guyasuta was among those who participated in this Battle of the Monongahela, which occurred near the present-day borough of Braddock, Pennsylvania. Washington and Guyasuta, however, did not engage in direct combat with one another. Washington, however, did exhibit some leadership in the fight, as British soldiers had panicked and retreated, but Washington reportedly rode back and forth across the battlefield, rallying British and Virginian forces into an organized retreat. In the process, Washington had two horses shot from beneath him while his coat was pierced with four bullets.

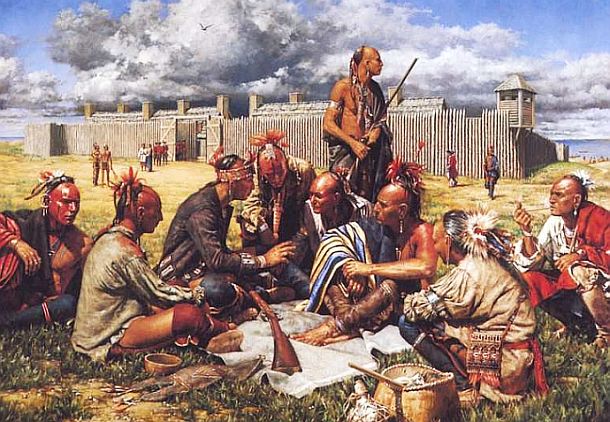

In Robert Griffing’s “Triumphant Return To Fort Duquesne,” Native American allies of the French are shown on their way back to the fort (barely visible at “forks” in the far distance) after defeating British General Edward Braddock in July 1755 at the Battle of the Monongahela, near present day Braddock, PA. Click for related book.

During the summer of 1758, a British detachment led by Major James Grant again advanced on Fort Duquesne ahead of a larger expedition, but this group too, was met by the French and Indians outside the fort in battle on what is now Grant Street. Guyasuta is believed to have fought in this battle, which ended in the defeat of Grant.

Close up of another Guyasuta statue, this one on Main St. in the Allegheny River town of Sharpsburg, PA, commemorating the Seneca chief’s history in that area.

The Forbes Expedition, under General John Forbes, captured the former Ft. Duquesne site for the British in the next day or so. As for Guyasuta, some accounts indicate that he then remained inactive for the remainder of the French and Indian War.

In October 1758, the Treaty of Easton was made with the British, in which the Indians ended their alliance with the French. In return, there was an understanding that the British would leave the area after their war with the French. Hostilities between the French and English declined significantly after 1760, followed by a final formal surrender of the French in 1763.

The British, however, had built their own new fort, Fort Pitt, in 1758 near the burnt ruins of Fort Duquesne. Guyasuta, for his part, was living peacefully in the area. But in the course of his travels, as he made occasional trading trips to Fort Pitt, he became familiar with the relative strength of the fortifications there. The British, meanwhile, had not lived up to their agreement to leave the area with the end of the French and Indian War.

In this painting, artist Robert Griffing depicts Indians over looking Fort Pitt (and what would become the city of Pittsburgh) from the northwest side of the Allegheny River, in the direction of Mt. Washington in the distance with the Monongahela River below. The British, rather than withdraw from the region after they had defeated the French – as they had promised – instead constructed Fort Pitt and turned the land around it into settlements. Click for Robert Griffing art book.

Although professing his basic good will toward those at Fort Pitt, Guyasuta was furious that British settlers were entering “Ohio Country” in great numbers, an abrogation of the earlier treaty as he saw it. So he reportedly became pleased when the Ottawa chieftain, Pontiac, began advocating an intertribal alliance against the British “intruders.” In implementing this plan, Pontiac was assisted by Guyasuta, who became a major player in Pontiac’s Rebellion or Pontiac’s War of 1763. Some historians, in fact, have referred to “Pontiac’s War” as the “Pontiac-Guyasuta War,” suggesting that Guyasuta was a major player. By July 1763, one of the targets in the uprising was Fort Pitt.

“The Conspiracy” by Robert Griffing, depicting part of the American Indian force that would become loosely allied in Pontiac’s Rebellion – these being Ojibwas at Fort Michilimackinac on Michigan’s lower peninsula. Click for related book.

Upon learning that a British relief column under Col. Henry Bouquet, was coming to Fort Pitt, marching west from Fort Bedford, Guyasuta led a large force to ambush them en route. Following two days of hard fighting in early August 1763, Bouquet’s troops beat back Guyasuta and his forces in the Battle of Bushy Run. Bouquet’s victory eventually forced Pontiac’s warriors to abandon their siege of Fort Pitt. With the ending of hostilities in Pontiac’s War in 1764, followed by two years of peace negotiations, Guyasuta lived quietly at various locales in Ohio. He also periodically occupied a small dwelling on the Allegheny River above Pittsburgh in the vicinity of present-day Fox Chapel.

“Point of View” sculpture with fuller profile of Guyasuta and only a partial view of Geo. Washington.

Washington’s Visit

In 1770, George Washington undertook his fifth trip to the western Pennsylvania. This time he came not only as a soldier but also as a farmer and investor. He then owned real estate in the area, including some land near Canonsburg and what is now Perryopolis.

On this trip, Washington stopped in Connellsville, visited Fort Pitt, dropped in on a friend at the town of Pine Creek (Etna today), and took a canoe ride down the Ohio.

On the river portion of the trip, Washington and his associates, Dr. James Craik and William Crawford, were looking for land and possible sites for what were called “bounty lands” – land grants awarded to soldiers and colonists who fought in the earlier wars.

It was on this trip down the Ohio River in October 1770, that Washington and Guyasuta would meet face to face for a second time – some 17 years after they had first met on Washington’s trek to the French Ft. Le Boeuf.

Both men by then had been seasoned by many battles and life on the frontier. And the country they both knew was changing around them. Washington was then 38 years old, Guyasuta, 45. Guyasuta was at his hunting camp when Washington met him, and according to reports, Guyasuta “held a perfect recollection” of Washington from their earlier meeting, despite the years that had passed. Guyasuta extended a hunter’s hospitality, giving Washington and his associates a quarter of a buffalo, just killed (and yes, there were bison in Pennsylvania at that time). He invited them to camp together for the night. And so, it was here that Washington and Guyasuta held long talks around the council-fire that night – the meeting upon which the “Point of View” sculpture is based.

1770: Washington and Guyasuta discussed land settlement restrictions, which were then being violated by settlers.

During their campfire discussions of that October 1770 meeting, land and its occupants were among the chief topics of conversation between Washington and Guyasuta. Both held differing views on settlement in the area, but reportedly, they parted on friendly terms. No one knows what was said, but tension surely arose over the apparent intentions of white settlers to violate the Proclamation of 1763, which was supposed to restrict white settlement west of the Alleghenies. Washington was in the area to survey in anticipation of such expansion and Guyasuta wanted the proclamation honored.

And again, in 1768, the treaty of Ft. Stanwix was supposed to have insured that all land west of the Ohio River was to remain native forever. But almost immediately, according to one account, Pennsylvania and Virginia vied for control of the new lands, sending settlers to stake claims in the Ohio country. The military, fur trading companies, and even some missionaries were all involved, ignoring the treaties. Some settlers instigated attacks on the Indians in hopes of precipitating another war that would help push the frontier further west. Following Pontiac’s War, many tribes were already disillusioned and had split into factions. Some resisted and raided white settlements, others wanted peace, and still others moved west. Additional pressure came from dislocated eastern tribes who had come to the region. “The Ohio country,” according to one historical account, “had become a bubbling cauldron of self-interest and greed.” By 1774, more surveying teams were in the region, followed by more settlement parties. It is no wonder that Guyasuta became dispirited about the fate of his homeland. (history continues below box & marker plaque).

|

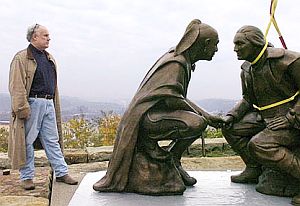

The Sculpture The “Point of View” sculpture of the 1770 meeting between George Washington and Indian leader Guyasuta on Pittsburgh’s Mount Washington, was installed in October 2006. It is the work of Pittsburgh-born Jim West, developer and sculptor. The idea for the project came about following a 2004 meeting between West and Lynne Squilla, then board president of the Mount Washington Community Development Corporation (MWCDC). At the time, Lynne Squilla was also researching the French and Indian War for a WQED/PBS documentary called “The War That Made America.”  Sculptor James West at positioning of his works, 2006. While Washington and Guyasuta did not meet on Mt. Washington per se, their sculpture would overlook the region where they had left their mark. Squilla and West went to the city with their idea, and then-mayor Tom Murphy embraced it. The city donated a small amount of land to the MWCDC for a “parklet” at the site and the Department of Public Works committed stones and Belgian block it had in stock for the pedestal. The Heinz History Center contributed details to the story.  Sculpture featured on cover of “Western Pennsylvania History,” Summer 2007. |

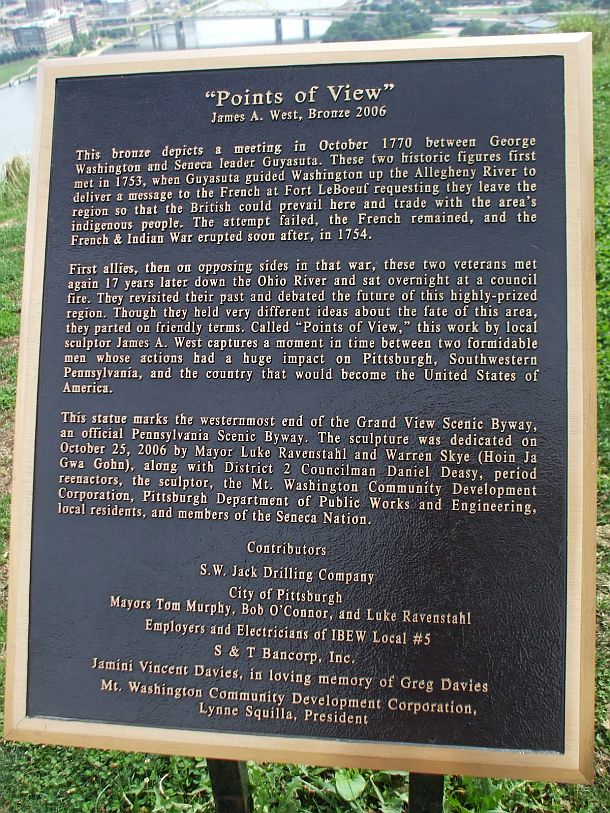

Explanatory marker at the Guyasuta-George Washington sculpture on Mt. Washington, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. This marker uses 'Points of View' to describe the Washington-Guyasuta meeting, although the sculpture was earlier named 'Point of View'.

1775-1799

Later History

In April 1775, as the American Revolutionary War began between the colonists and the British, Guyasuta was initially neutral. As a highly regarded leader in the Iroquois Confederation in the Ohio Valley, he met with envoys from both sides. At one point he was offered a military position with the Colonial army. But Guyasuta ultimately chose to ally with the British and against the colonists. During the next several years, he reportedly led raids from Ohio, as well as New York, into western Pennsylvania. In August 1779, the Fort Pitt commandant, Col. Daniel Brodhead, led an expedition up the Allegheny to destroy an enemy force. He encountered Guyasuta’s war parties in the process. Some reports indicate Guyasuta’s participation in raids as late as July 1782.

George Washington, meanwhile, was made commander of the Continental Army in June 1775, and for the next several years, would have his hands full trying to keep his army together while fighting the British throughout the colonies. The Colonists formally made their Declaration of Independence from Great Britain in July 1776. By 1777, the French had allied with the American colonists and Washington’s Continental Army. Washington’s troop of 11,000 soldiers, which had been engaged in a number of battles, went into winter quarters at Valley Forge north of Philadelphia in December 1777. The British, meanwhile, were sometimes aided in battle against the colonists and the Continental Army by American Indian allies, whose raiding parties took a toll on American settlements.

Reproduction of 1907 painting by John Ward Dunsmore, “Washington and Lafayette at Valley Forge,” depicting the winter encampment of Washington's troops in 1777 ( Brown & Bigelow, St. Paul and Toronto). Click for related book.

The Sullivan Expedition. In the summer of 1779, after suffering nearly two years from Iroquois raids on the Colonies’ northern frontier, George Washington and Congress decided to strike back. The Iroquois had used their New York villages as a base to attack American settlements across New England. In June 1779, for example, the warriors had joined the British to kill over 200 frontiersmen while laying waste to the Wyoming Valley in northern Pennsylvania. Washington then ordered what at the time would be he largest-ever campaign against the Indians in North America, an action that authorized the “total destruction and devastation” of the Iroquois settlements across upstate New York. The Sullivan Expedition then defeated the loyalist Iroquois army, burned 40 Iroquois villages to ashes, and left homeless many of the Indians, hundreds of whom died of exposure during the following winter. Indeed, some years later, [in 1790], the Seneca chief Cornplanter, nephew of Guyasuta, would tell President George Washington: “When your army entered the country of the Six Nations [i.e. New York state], we called you Town Destroyer.”

Engraving from “A Popular History of the United States” by William Cullen Bryant (1892) depicting a scene of the torching of an Indian village during the Sullivan Expeditions of 1779 aimed at vanquishing the Iroquois. Click for related book.

As the Revolutionary War continued, Washington’s army persevered in the fight. The surrender of the British at Yorktown October 19, 1781– with the help of the French – marked the end of major fighting in continental North America, though some smaller skirmishes would continue for some time. By September 1783, with the signing of the Treaty of Paris, Great Britain recognized the independence of the United States. Washington disbanded his army not long thereafter, and would resign as commander-in-chief on December 23rd, 1783.

At the conclusion of the American Revolutionary War, Guyasuta chose to reside near Pittsburgh, although most of his closest relatives had emigrated to western Ohio. With dismay, he watched as his native country changed before his eyes. After the signing of the second Fort Stanwix treaty of October 1784 in New York, large swaths of former Iroquois/Seneca hunting grounds west of the mountains and north of the Allegheny River were opened to white settlement. Financial inducements and public policies, including the Depreciation Lands Act of 1783, a Settlers Land Act of 1792, and other measures, would help expedite settlement. It would soon no longer be the same country that a young Guyasuta had roamed and once called home.George Washington, meanwhile, would be elected first president of the United States in 1789 and elected again for a second term in 1792. After retiring from the presidency in March 1797, Washington returned to Mount Vernon, tending to various projects on his estate. But one day in mid-December 1799, after inspecting his plantation on horseback in snow and freezing rain, Washington delayed changing out of his wet clothes and became ill. He died two days later at home on December 14th, 1799. He was 67 years old.

Guyasuta, meanwhile, spent his final days in a log cabin on land in the vicinity of Sharpsburg – the gift of a former ally, General James O’Hara, a British officer. O’Hara owned land at Sharpsburg. One story has it that O’Hara once saved the life of Guyasuta, treating him after he had been bitten by a rattlesnake. Guyasuta is believed to have been around 70 years old at his death in 1794. According to one account, after not being seen for several days, O’Hara found him dead on his cabin floor. By then, alcohol had the better of him, having been despondent over the fate of the Indian lands. There are conflicting accounts as to where he is buried. One report contends he was buried on land granted to his nephew, Cornplanter. Another has it that O’Hara buried the old chief in the Indian mound on the estate, a grave site said to have been visible for much of the 19th Century. Later, the Pennsylvania Railroad created a track line near Guyasuta’s burial site and by 1900, created Guyasuta Station near Sharpsburg as a belated tribute to the Seneca warrior.

Close up of the “Point of View” sculpture on Mt. Washington, Pittsburgh, PA, looking out at the regional viewshed in a north-northeast direction along the Allegheny River. Photo, James West, website, http://studiowildwest.com

The “Point of View” sculpture in any case, now overlooking the Pittsburgh metropolitan region, is a fitting tribute to Guyasuta’s concerns for his homeland and the fate of the country. It is also a good reminder of the clash of cultures and perspectives that occurred in America at its founding and settlement – and in some ways offers a parable of bucolic loss, at least from the Native American perspective. And as its namesake suggests, the sculpture also highlights the differing views on the use and ownership of land and resources at that time and how a new country would be developed — for good and for ill.From their campfire along the Ohio River of 1770, Washington and Guyasuta would surely be astonish- ed at the Pittsburgh region today. For in a relatively short span of time, the Pittsburgh region – as it is viewed today from the Mt. Washington vantage point, stretching out across the “forks of the Ohio” and beyond – went from untamed wilderness to paved-over metropolis. It is now a region where today millions of people move around at all hours of the day and night in personal transportation vehicles traveling at speeds of 60 and 70 miles per hour, a truly unfathomable and unimaginable notion at the 1770 campfire of George Washington and Guyasuta. Indeed, what will the Pittsburgh region look like 250 years from now?

Additional Pittsburgh-related stories at this website include, for example: “The Mazeroski Moment” (1960 World Series), “$2.8 Million Baseball Card” (Honus Wagner), and “Disaster at Pittsburgh”(1988 oil tank collapse and river pollution). For other story choices please visit the Home Page or the Archive. Thanks for visiting – and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research and writing at this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

____________________________________

Date Posted: 13 April 2016

Last Update: 3 April 2020

Comments to: jackdoyle47@gmail.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Point of View – George & Guyasuta,”

PopHistoryDig.com, April 13, 2016.

____________________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

“George Washington: Surveyor and Map- maker,” U.S. Library of Congress.

C. Hale Sipe, The Indian Chiefs of Pennsylvania, Ziegler Printing Co., Inc.,: Butler, Pennsylvania, 1927.

Miles Richards, “Exploring History: The Mighty Guyasuta,” TribLive.com, June 25, 2014.

Joel Achenbach, “The Smartest Route to Pittsburgh: The One with No Shortcuts,” Washington Post, July 16, 2015.

Al Lowe, “Washington Will Meet Guyasuta Once Again on Mt. Washington,” South Pittsburgh Reporter, October 17, 2006.

“George Washington,” Wikipedia.org.

Diana Nelson Jones, “In Sculpture, Seneca Leader Guyasuta Reunited with George Washington; The Site of a New Sculpture Affords a View of the Place Where the Historical Figures Met Near the Confluence of the Monongahela and Allegheny Rivers,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, October 20, 2006.

Brady J. Crytzer, Major Washington’s Pittsburgh and the Mission to Fort Le Boeuf, The History Press, April 2011, 128 pp.

Brady J. Crytzer, Guyasuta and the Fall of Indian America, Westholme Publishing, June 2013, 352 pp.

“Guyasuta,” Wikipedia.org.

“Mt. Washington Has A New Point of View,” View Point (Mt. Washington newspaper), November 2006.

Edward A. Galloway, “Guyasuta: Warrior, Estate, and Home to Boy Scouts,” Western Pennsylvania History, Winter 2011-12, Volume 94, Number 4, pp. 18-31.

Rick Sebak, “George Washington’s 7 Trips to Pittsburgh Were Certainly Eventful; A Look Back at Our Nation’s First President’s Many Visits…,” Pittsburgh Magazine, January 29, 2014.

William M. Darlington, Christopher Gist’s Journals with Historical, Geographical and Ethnological Notes and Biographies of His Contemporaries, [Part 7] Pittsburgh, J. R. Weldin & Co., 1893, pp. 202-240.

“James A. West, Sculptor,” Website.

“Mount Washington (Pittsburgh),” Wikipedia .org.

History of the Borough of Sharpsburg.

Kristin Hopper, “President George Washing- ton,” WordPress.com, 2010.

Larry Pearce, “Meet Native American Guyasuta,” March 6, 2008.

Johannah Cornblatt, “‘Town Destroyer’ Versus the Iroquois Indians; Forty Indian Villages—and a Powerful Indigenous Nation—were Razed on the Orders of George Washington,” U.S. News & World Report, June 27, 2008

Barbara Graymont, The Iroquois in the American Revolution, Syracuse University Press, December 1975, 4th edition, 359 pp.

“Siege of Fort Pitt,” Wikipedia.org.

Paula W. Wallace, Indians in Pennsylvania (1st edition, 1961 ), Diane Publishing Inc., 2007, 200 pp.

“Capture of Fort Duquesne,” ExploringOff TheBeatenPath.com(excellent source).

______________________