In 1958, the game of professional football occupied a distinctly different position in America’s economy and culture than it does today. There were no Super Bowls then and certainly no $150,000-per-second TV ads during any sporting event. Baseball was then America’s most popular sport, by far. In fact, through most of the 1950s, college football was more widely followed than professional football. But in late 1958 a sea change was about to come to professional football; a change that would set the game on its present course as big-time business, taking over a large part of American sports culture and American Sunday afternoons for five or more months of the year.

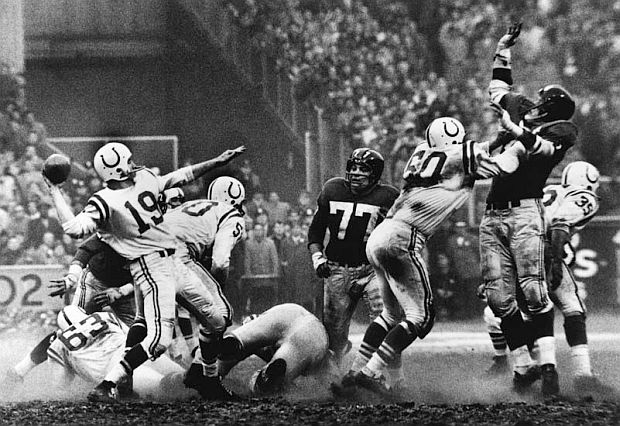

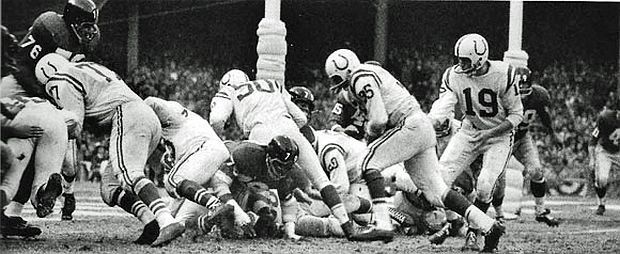

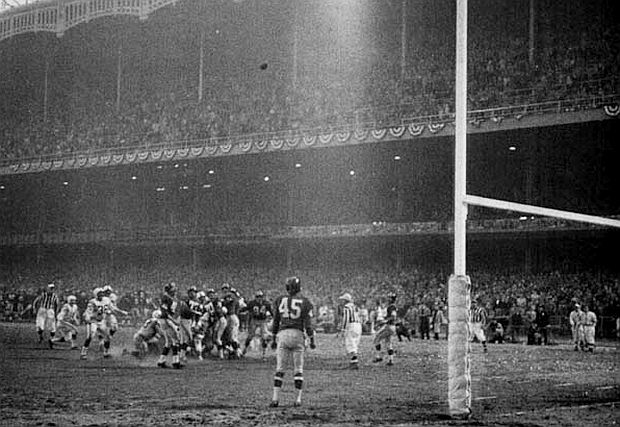

December 28, 1958 game-changer: Famous photo from Baltimore Colts vs. New York Giants NFL championship game; the game that launched a new era of big time pro football sports culture & big business. Baltimore Colts quarterback, Johnny Unitas, No. 19, shown here about to throw one of his passes.

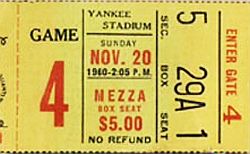

The historic moment marking the beginning of this transformation came more than 60 years ago now, on December 28th, 1958 at the meeting of the Baltimore Colts and the New York Giants in a professional football game played at New York’s Yankee Stadium. In those days, this season-capping football showdown was simply called a National Football League (NFL) championship game. There was only one football league then, the NFL, consisting of two conferences, East and West, each with six teams. The championship game, however, wasn’t just any old championship game. No, it happened that there was a pretty impressive lot of talent out on the field that day – a number of whom would later join the pro football Hall of Fame. The game was also nationally televised, still something of a rarity for professional football at the time. But this particular mix of elements would make for a pretty exciting afternoon – and more. “That’s the game that changed professional football,”famous Hall of Fame football coach Don Shula would say some years later. “The popularity of it started right there.”

1950s America

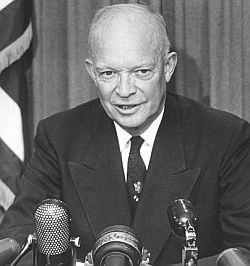

Dwight D. Eisenhower, U.S. President 1953-1961.

In terms of consumer amenities in those years, there were no iPhones, of course, no PCs, no big-screen TVs. In fact television then had three primary channels, viewed mostly on small black-and-white sets. TV westerns were a dominant genre in the 1950s, and Gunsmoke, with actor James Arness, was among the most popular shows.

In music, Billboard magazine debuted its “Hot 100″ music chart in July 1958, and Ricky Nelson’s “Poor Little Fool” became the first No.1 hit. In Hollywood, South Pacific, a romantic musical film based on the Rodgers and Hammerstein stage production of the same name, would become the year’s top grossing film. In September that year, Bank of America introduced the first credit card.

President Eisenhower, meanwhile, who had played halfback on the West Point football team, watched the 1958 NFL Championship Game that day between the Baltimore Colts and the New York Giants. He tuned in from Camp David, joining millions of others who also watched the game.

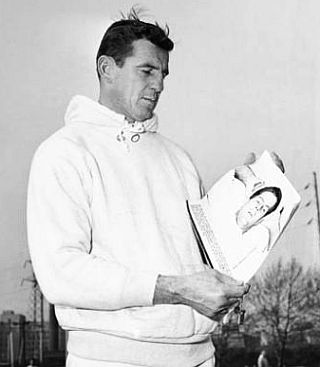

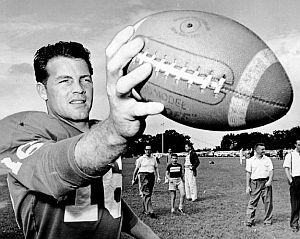

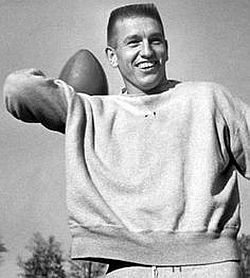

Colts QB, Johnny Unitas, at a 1950s practice session, about to throw a pass.

Regular Guys

Professional football players in those days, for the most part, did not have the exalted status and multi-million-dollar paydays they would come to have years later. Most in fact, were then pretty much like everybody else; like normal people. Some even lived in row houses.

A guy named Johnny Unitas who happened to be the quarterback on the Baltimore Colts professional football team, had recently helped his teammate, fullback Alan Ameche, lay out his kitchen floor in the row house that Ameche and his wife had bought.

Professional football salaries were such that some players held other work-a-day jobs during their football careers. Unitas, in fact, worked at Bethlehem Steel during the off-season for extra cash. Another Colt, defensive lineman Art Donovan, worked as a liquor salesman.

Football Drama

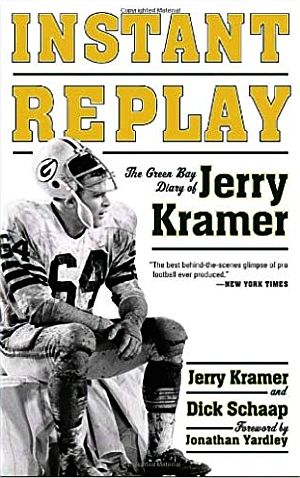

But in late December 1958, Unitas, Ameche, Donovan and their teammates would travel to New York’s Yankee Stadium for a professional football championship showdown with the New York Giants that some believe was one of the greatest games ever played. It would also be the game that catalyzed a major change in the fan base for pro football, and generally, in its economics as well.“I knew nothing about pro football when the game began and was hooked for life when it ended. So too were millions… of other Americans…”

– Jonathan Yardley Of fans who saw the game that day – either among the reported crowd of 64,185 who filled the old Yankee Stadium, or the millions who watched on television – many came away believing they had witnessed a very special contest indeed. Washington Post writer, Jonathan Yardley, recalled some years later that his football conversion occurred watching this game on television as a young man – a game, he would later write, “for which the only appropriate adjective was, and remains, thrilling.” Yardley was 19 years-old at the time, home from college for Christmas vacation. Bored to tears with nothing much to do, he had found a black-and-white television set in a recreation room at the school where his father was headmaster – “to which I retreated in desperation the afternoon of December 28th.” Yardley recounted that “he knew nothing about pro football when the game began, but was hooked for life when it ended. So too were millions – literally millions – of other Americans…” More on the game in a moment; first some background on how the two teams got there.

The ’58 Season

In 1958, the New York Giants and the Baltimore Colts were the respective champions of their divisions. Each team had complied 9-and-3 records that season, pro teams then playing a 12-game schedule as opposed to 16 today. Baltimore had won their first six games, standing at 6-and-0 until losing to the Giants in a regular season contest, in part because quarterback Johnny Unitas was out due to an injury. In any case, the Colts clinched the Western Conference title by Game 10, beating San Francisco, then able to rest their starters for the remaining two games of the regular season, which they lost.

Dec 14, 1958. Pat Summerall kicks winning field goal in the snow against the Browns to advance Giants to playoff game.

On December 14th, 1958, the 8-3 Giants faced a 9-2 Cleveland Browns team — their last regular season game and their last shot at a possible Conference title. That game came down to a 10-to-10 tie in closing minutes of play on a cold, snowy afternoon.

It was then that the call went out to Giant’s place kicker, Pat Summerall, to attempt a 49-yard field goal in the driving snow. The pressure was on. Ending in a tie game would mean Cleveland would go to the Championship game, not the Giants.

Summerall made the kick, despite the freezing conditions, sending the ball through the uprights, and lifting the Giants to a 13-10 win. But that wasn’t the end of it.

Giants managed to hold NFL’s leading rusher, Jim Brown (32) of Cleveland to 8 yds in Dec 21, 1958 playoff game.

That meant a playoff game would be needed to determine the Eastern Conference champion. So that game was played the following week on December 21st, 1958 at Yankee Stadium.

Jim Brown of Cleveland was a punishing and powerful fullback for Cleveland, who had gained a record 1,527 yards rushing that year. In the playoff game, however, the Giants managed to hold Brown to a mere eight yards total rushing – no mean feat – and won the game, beating Cleveland 10-0.

Then, a week later, came the NFL Championship game against the well-rested Baltimore Colts, to be played on the same Yankee Stadium field where the Giants had just beaten the Browns – a field worn by the previous weeks’ battles, and much of it on the baseball diamond’s bare-dirt infield. These were not the days of well-manicured Super Bowl fields and climate controlled superdomes.

|

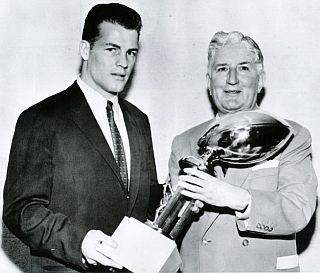

The Hall of Fame 15 New York Giants Baltimore Colts |

Talented Teams

The nationally-televised NFL Championship Game was broadcast by NBC and watched by some 50 million people. The broadcast would help open the floodgates to more televised professional football contests thereafter, and the sport’s rising popularity via television in the 1960s and beyond. And the fact that it was being played in media-centric New York, even then, meant that it would receive a fair amount of press attention.

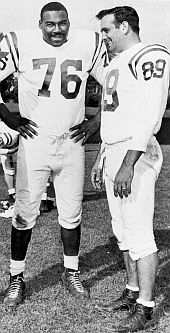

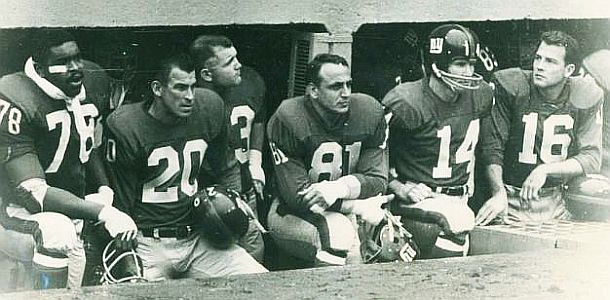

On the field that day there were 12 players and 3 coaches – including Colts’ quarterback Johnny Unitas and hulking Giants linebacker Sam Huff – who would later be inducted into the Football Hall of Fame. (see later sidebar below for brief player profiles).

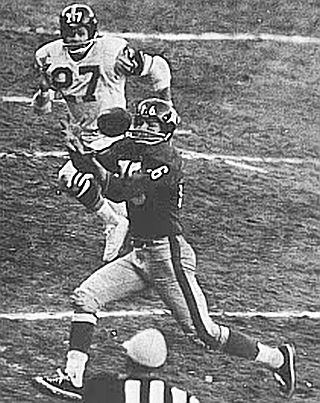

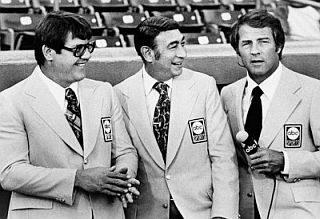

Unitas and the Colts also had Lenny Moore at halfback, wide receiver Raymond Berry, and all pro defensive end, Gino Marchetti. The Giants, in addition to Huff’s formidable defensive talents, had a potent backfield in Frank Gifford at halfback (also a passing threat), Alex Webster at halfback, and fullback Mel Triplett.

This particular game, in addition to its playing talent, would also have some of game’s rising strategic thinkers and coaching personnel, especially in the case the Giant’s offensive coordinator, Vince Lombardi, and Giant’s defensive coordinator, Tom Landry, both of whom would later rise to have standout seasons and Super Bowl victories as head coaches — Lombardi with the Green Bay Packers and Landry with the Dallas Cowboys. The Super Bowl trophy, in fact – the Lombardi Trophy – is named after Vince Lombardi. And for the Colts as well, head coach Weeb Ewbank would go on to other coaching successes, notably winning Super Bowl III with the New York Jets and quarterback great, Joe Namath.

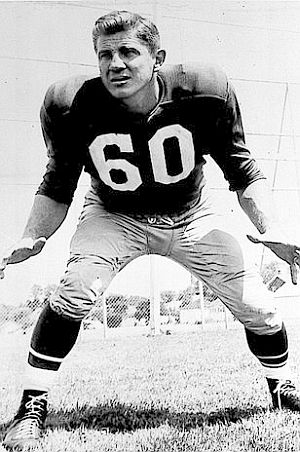

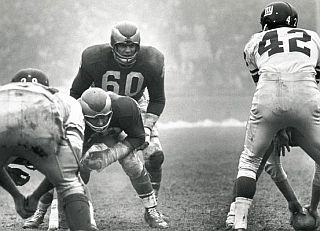

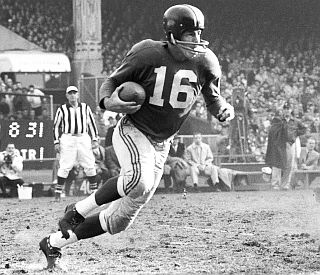

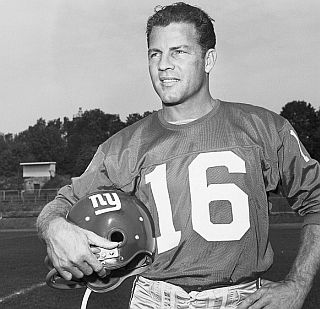

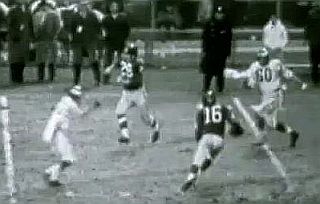

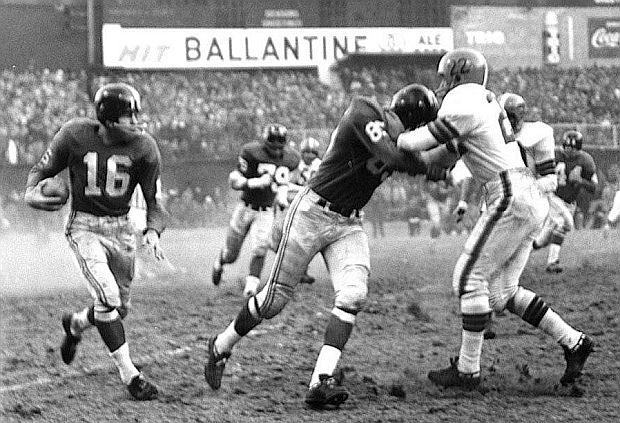

Frank Gifford (16), star halfback for the New York Giants, shown in an earlier 1958 game, running against the Cleveland Browns, as offensive end, Bob Schnelker (85), blocks ahead of Gifford, with other Giants, offensive tackle Rosey Brown (79) and half back Kyle Rote (44), visible in the background and headed downfield.

The 1958 championship game would also have high drama, as it would go into sudden-death overtime – the first time that had ever occurred in an NFL game. And in the wake of this game, new football celebrities were created and pro football as a sports business was about to become a much bigger enterprise.

For the Giants, backup QB Don Heinrich would start the game, as he and regular QB Charlie Conerly had routinely shared the position in the early minutes of each game throughout the season. The Giants’s coaching staff liked to use Heinrich for the first few series to “feel out” the opposition so that offensive coordinator Vince Lombardi and Conerly could look over the defense from the sidelines. Along with their other coaches in the press box, the Giants could then modify the game plan for Conerly when he entered the game. At least that was the plan.

Colts’ Lenny Moore (24) about to catch a Unitas pass. (graphic, Robert Riger).

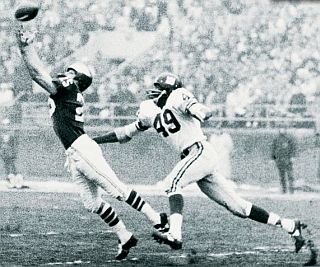

The Giants then went three-and-out. Baltimore began moving on its possession, as Unitas completed a 60-yard pass to Lenny Moore at the Giants 26-yard line, establishing speedster Moore as a big threat. But Baltimore’s drive was slowed, and they were forced to make a field goal try at the 19 yard line.

Kicker Steve Myhra, who made only 4 of 10 FGs during the season, missed the kick from about the 31 yard line. However, the Giants were offside, so Myhra got another chance, this time from about the 26. However, Giant linebacker Sam Huff broke through the Colt line and blocked the kick.

As the Giants took over, QB Charlie Conerly then came in and moved New York to the Colts’ 30-yard line, featuring a 38-yard run by Frank Gifford. On a third-down play, Conerly threw a pass to wide-open fullback, Alex Webster, who slipped on the turf just as the ball arrived, sailing past him and falling incomplete. If caught, however, this one might have been a Giant’s touchdown. Pat Summerall then kicked a 36-yard field goal to put New York on the board. Giants 3, Colts 0.

Second quarter. During the second quarter, the line play of both teams began to be a telling feature of this game, as some of New York’s standout defenders, like Roosevelt “Rosey” Grier, playing with a a bad leg, wasn’t at full power. Halfback Frank Gifford would have his problems as well. Giant QB Conerly tossed to Gifford in the left flat. But as Gifford tried to break the tackle of Colt defensive lineman, Gene “Big Daddy” Lipscomb (6′-6″, 285 lbs), the ball popped out and Colt defensive tackle, Ray Krouse, fell on it at the New York 20-yard-line.

December 28, 1958 NFL championship game at Yankee Stadium, as New York Giant’s halfback, Frank Gifford, No. 16, looks for running room as Baltimore Colt defenders – including “Big Daddy” Lipscomb No 76 -- close in.

The Colts then took over with mostly running plays: Lenny Moore ran for 4 yards, Ameche for 5, and then again for a yard more and a first down. The Colts were now at the ten-yard line. Moore then tried a run around left end, was almost taken for a loss by Colt defensive back Karl Karilivacz, but broke free briefly until Colt defensive back Jimmy Patton pushed him out at the 2-yard-line. From there, Unitas gave the ball to fullback Ameche (photo below) who took it in for a score behind the blocking of left tackle Jim Parker. Myhra’s point-after-touchdown kick then added the extra point. Colts 7, Giants 3.

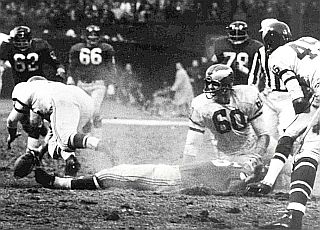

Alan Ameche, No. 35, takes hand-off from Colt quarterback Johnny Unitas, No, 19, to score on a two-yard run in the 2nd quarter after Giant’s Frank Gifford had fumbled at that end of the field, putting the Colts in the lead, 7-to-3.

The Giants made little progress after receiving the Colt’s kick, and after a series of plays had to punt. The kick to the Colts, however, was fumbled by Jackie Sampson, with the Giants recovering on the their 10-yard line. But the Giant’s were unable to capitalize, as Frank Gifford, on a sweep play left, fumbled again late in the second quarter when hit by Colt defensive back Milt Davis. On the Giant’s defensive line about that time, tackle Rosey Grier took himself out of the game, as his leg injury had hobbled him by then. With thin reinforcements, the Giants were forced to use an offensive tackle, Fran Youso, to replace Grier for the rest of the game.

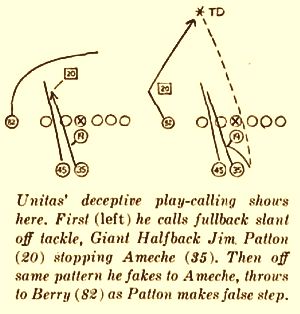

Play diagrams & explanation from ‘Sports Illustrated,’ January 1959 issue (more detail, later below)

From there, Ameche gained 6 more yards. Then Unitas faked to Ameche, as in the previous running play, drawing in Colt defender Jimmy Patton (#20), who thinks it’s a run. But instead, Unitas then turns and fires a 15-yard-pass to Berry who is wide open in the end zone. Touchdown! (see diagram at right). Myhra then added the extra point. Colts 14, Giants 3.

Sam Huff would later say of his nemesis that afternoon, Johnny Unitas:

“You couldn’t out-think Unitas. When you thought run, he passed. When you thought pass, he ran. When you thought conventional, he was unconventional. When you thought unconventional, he was conventional. When you tried thinking in reverse, he double-reversed. It made me dizzy. It bothered me. We were one of the greatest defensive teams ever put together. … But we didn’t have a defense for Unitas.”

Third Quarter. The Colts received the kickoff at the opening of the second half, and Unitas, with continued good protection from his offensive line, moved the Colts down the field with passing in two series of downs before punting to the Giants. But the Giants went 3-and-out, punting the ball back to the Colts. This time, Unitas moved the Colts down the field to the Giant three-yard line, first down and goal to go. A sure touchdown seemed certain. Giant fans were about to throw in the towel. But the Colts were stopped cold by the Giant defense there on four attempts, including a quarterback sneak attempt by Unitas. But the Colts, surprisingly, did not opt for a field goal. On successive 3rd and 4th down running attempts by fullback Ameche, as the Giant defenders held the line

Alan Ameche, Colts fullback, and key workhorse in the game, mis-heard play call that might have been TD.

The Giants then took over, giving team and fans hope they would prevail. It was one of the game’s key turning points in what was becoming an exciting see-saw battle.

Still, backed up against their own endzone, the Giants had their work cut out for them. They had 95-yards to go. A key play came on a Conerly pass to Kyle Rote who caught the ball on a long crossing route, broke an arm tackle at about mid-field, but then fumbled when he was hit from behind at around the 25 yard line. Fortunately for the Giants, running back Alex Webster wasn’t far behind, and although some Colt players were closing in on the fumble, Webster managed to pick up the ball and ran downfield until he was knocked out-of-bounds at the one-yard-line. From there, Giant fullback Mel Triplett took the ball in for the score. Summerall kicked his first extra point of the day. Colts 14, Giants 10. The psychology of the game suddenly shifted in the Giant’s favor – or so it seemed.

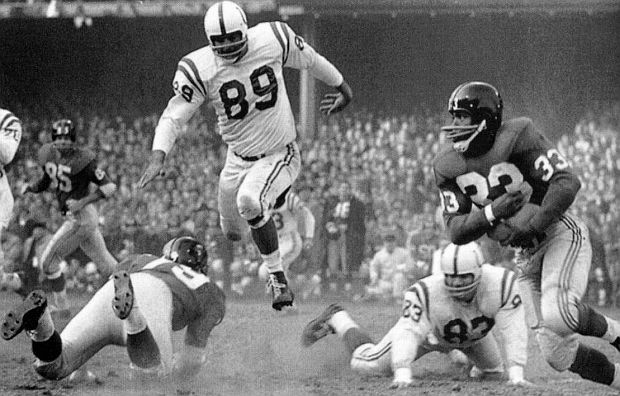

Mel Triplett (33), NY Giants’ fullback, on the move during the 1958 NFL Championship Game, as Colt’s defensive lineman, Gino Marchetti pursues him. Triplett would score Giant touchdown in the 3rd quarter..

The Giants continued their momentum, sacking Unitas for a loss to force a three-and-out for the Colts. Starting the next possession from their 19, the Giants began moving again. Webster ran for 3, then Conerly hit tight end Bob Schnelker with a pass for 17 yards as the third quarter ended.

Fourth Quarter. Then early in the fourth quarter, with the Giants still with the ball, Conerly hit Schnelker again, followed by a 15-yard pass to Gifford who caught it at the 5 yard line, then carrying defender Milt Davis with him into the endzone for the score. With the extra point, it was now Giants 17, Colts 14.

The Baltimore Colts in the fourth quarter were able to move the ball into scoring range on two occasions, but came up short both times. First they made it to the Giants 39-yard line, but kicker Bert Rechichar missed a 46-yard field goal attempt. On another drive after a fumble recovery, they moved the ball to the New York 42 yard line, and then to the 27-yard line. But here, Unitas was sacked twice in a row – once by Giant’s defensive tackle, Andy Robustelli, and once by Giant’s defensive end, Dick Modzelewski. These losses pushed the Colts back by 20 yards or so and out of field goal range.

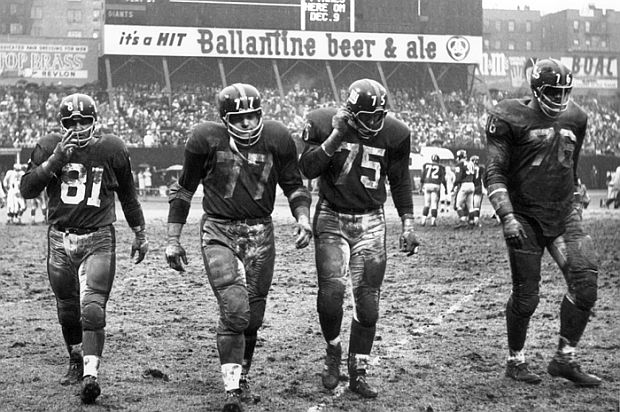

New York Times photo from November 1962: NY Giants defensive lineman, from left: Andy Robustelli, Dick Modzelewski, Jim Katcavage and Rosey Grier, were also key Giant players in 1958. Photo Dan Rubin.

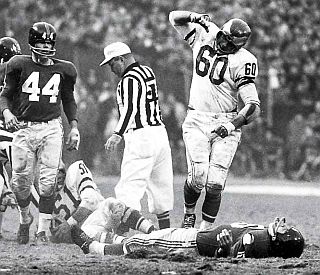

With less than three minutes left in the game when they received the Colts punt, the Giants were trying to run out the clock through a series of plays and hold their lead. But then they faced a crucial third-down-and-4-yards-to-go, needing a first down for a fresh set of plays. They were on their own 40 yard line. Gifford was given the call on a sweep play, and appeared to have the first-down as he was tackled by Colt’s defensive end, Gino Marchetti. Also joining in on the tackle was Colt teammate “Big Daddy” Lipscomb who fell on Marchetti, breaking his lower leg bones above the ankle. Some say Marchetti’s yelling in pain had distracted the officials resulting in a bad spot of the ball marking the end of Gifford’s run. Gifford believed – and would maintain for years thereafter – that he had made the crucial first down. But at the time, the ball was placed just short of the marker.

Sports Illustrated artists’ rendition of key 4th quarter play from 1958 Championship game when Colt’s Gino Marchetti (89) makes tackle of Giant’s Frank Gifford (16), as Colt’s Big Daddy Lipscomb (76) joins in, when the tibia and fibula bones in Marchetti's lower right leg were broken, afterwhich officials made a controversial spot of Gifford’s advance just short of a first down.

This meant the Giants were then at a pivotal fourth-down moment. They were inches away from a possible first down, which if made, would help them continue to eat up the clock, hold their lead, and win the game. Should they go for it or punt? Offensive coach Vince Lombardi urged Giant head coach Jim Lee Howell to go for it, as did defensive coach Tom Landry. Giant players wanted to go for it as well, thinking they had a better shot at running the ball at Marchetti’s replacement, Ordell Brase. Giant’s offensive guard, Jack Stroud, would later say: “We only need four inches. We would have run through a brick wall at that point.” There was a little over two minutes remaining.

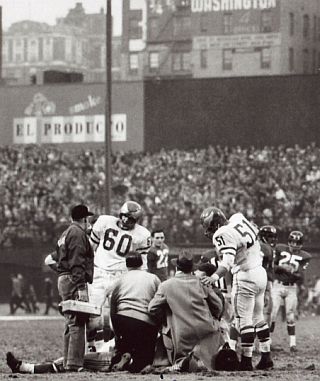

Injured Colt Gino Marchetti on sideline.

Back on the Giant’s sideline, head coach Jim Howell was still pondering his fourth down decision. He elected to punt, believing his defense could protect the Giants 17-to-14 lead and hold the Colts in the remaining minutes.

The punt by Giant’s Don Chandler pinned Baltimore back on their own 14 yard-line with about two minutes remaining in the game. As the Colts took the field, wide receiver, Raymond Berry recalled: “I said to myself, ‘Well, we’ve blown this ballgame.’ The goalpost looked a million miles away.”

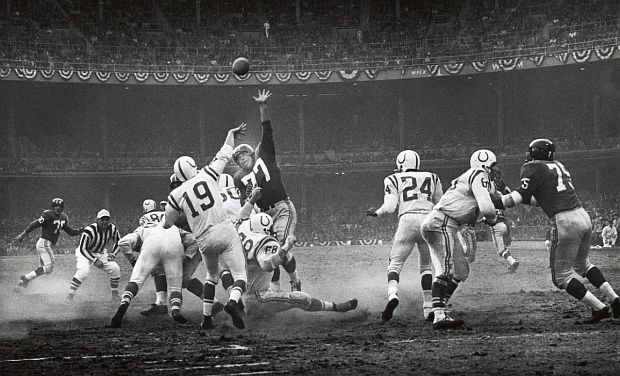

With 1:56 left and no timeouts, a Johnny Unitas legend was about to begin. From that point, Unitas engineered one of the most famous drives in football history – what might be called a “2-minute drill,” though before anyone used that term. His first two throws were incomplete, but Unitas made a third down, 11-yard completion to Lenny Moore. After a first down throw went incomplete, Unitas then threw three consecutive completions to Raymond Berry for 25, 15 and 22 yards, moving the ball 62 yards down the field to the Giants 13-yard line as time nearly ran out. This set up a 20-yard field goal by Myhra with seven seconds left to play. Myhra, in fact, wasn’t just a kicker that day, as he had been playing most of the game, since the first quarter, replacing injured left linebacker Leo Sanford. Nor was Myhra’s record exceptionally good, having made only 4 of 10 field goal attempts during the season. But this time, with seven seconds left, Myhra hit the 20-yard field goal, tying the score – Giants 17, Colts 17.

1958. With 7 seconds remaining in the championship game, Colts kicker, Steve Myhra, successfully boots one through the uprights from 20 yards out, tying score with the Giants, 17-to-17. Ball in flight is visible, upper center.

As the final seconds ticked away in the deadlocked contest, many of the players thought the game was over and would end as a tie. Some began heading to the locker rooms only to be admonished by the officials that a “sudden death” overtime period was about to begin. It was the first overtime game in NFL playoff history.

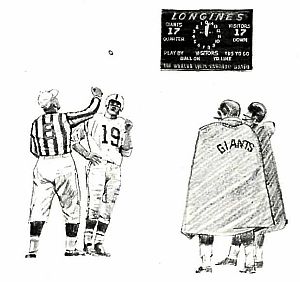

Sports Illustrated artist’s rendition of coin toss for “sudden death” period, showing Johnny Unitas for the Colts and co-captains for the Giants, Kyle Rote and Bill Svoboda.

As Johnny Unitas later recalled:: “When the game ended in a tie, we were standing on the sidelines waiting to see what came next. All of a sudden, the officials came over and said, ‘Send the captain out. We’re going to flip a coin to see who will receive.’ That was the first we heard of the overtime period.” The respective player-captains came to the center of the field for the coin toss. Unitas called for the Colts, but lost the toss. The Giants would receive. “The first team to score, field goal, safety, or touchdown,” the referee explained to the captains, “will win the game, and the game will be over.”

Across America, meanwhile, as the special overtime period began, TV viewers and radio listeners were transfixed. This game was providing a new kind of athletic drama. On the NBC-TV broadcast, Colts announcer, Chuck Thompson, offered that “something historic” was happening “that will be remembered forever…”

In the overtime period, Don Maynard received the opening kickoff for the Giants, bobbled the ball a bit, but held onto it as he was tackled at the Giants 20-yard line. Giants quarterback, Charlie Connerly, the 37-year-old veteran, then came in, and his first play went to halfback Frank Gifford, who gained four yards. Then Conerly faked a draw play, as receiver Bob Schnelker was sent downfield for about ten yards, deep enough for a first down, but Conerly’s pass just missed him, as Schnelker made a valiant dive attempting to reach it. With a third-down-and-six-to-go, Conerly tried to pass again, but his receivers were covered, so he tried to run for it, moving around the Colts right end, but was hit by Colt linebacker Bill Pellington first, then lineman Don Shinnick, who brought Conerly down just short of the first-down marker. The Giants then punted and the Colts took over.

Earlier in the game, Giants quarterback, Charlie Conerly (42), had been having a pretty good day, shown here throwing a jump pass over on-rushing Colt defenders. But in the overtime period, the Giants seemed to run out of gas.

As the Colts took possession of the ball in the overtime period following the Giant’s punt, once again, the field command of quarterback Johnny Unitas would be put to the test – and he did not disappoint. Unitas took his team 80 yards down the field in 13 plays, as a tired Giant’s defense tried to keep up.

The first play was a run by halfback Louis Dupre over right tackle for 11 yards to the 31. Next, Unitas threw a long pass for Lenny Moore down the sideline, but Colt defender, Lindon Crow, broke it up. Dupre was called again for a two-yard run. It was then 3rd-down-and-8-to-go. On this crucial play, wide receiver Raymond Berry headed downfield on a passing route, but Unitas tossed a flare pass in the flat to Ameche who took it eight yards, just enough to make the first down at the 41 yard line. Dupre that ran again for a gain of four yards.

Photo shows Colt QB, Johnny Unitas (19), in action during NFL Championship Game, throwing pass over the attempt of hard-charging NY defensive tackle, Dick Modzelewski (77), to unsuccessfully block it.

On the next play, Giants’ tackle, Dick Modzelewski, broke through the Colt line and sacked Unitas for a loss of eight yards. It was then 3rd down. The Colts were on their own 37 yard-line and needed 14 yards for first down. On the that 3rd down play, Unitas was rushed by Colt defenders, but evaded them and threw to Berry, who had come back for the ball off his pass route, gaining 21 yards for the first down and crossing midfield to the Giant’s 42 yard-line.

As Unitas came to the line for the next play, he had been feeling the pressure of Giant’s hard-charging defensive tackle, Dick Modzelewski. So Unitas this time called an “audible” at the line – a change of play – signaling a trap block on Modzelewski from left Colt guard Art Spinney (63) who would cut across center laterally “trapping” Modzelewski (77) with a good block (see illustration below), while the other Colt’s guard, George Preas (60) went after Giant linebacker Sam Huff (70), clearing the way for fullback Alan Ameche who then went for a gain of 23 yards downfield. A nicely timed play which then put the Colts on the Giant’s 19 yard line.

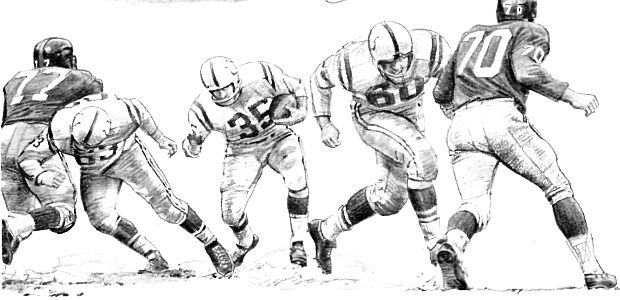

Artists rendition from ‘Sports Illustrated’ showing key “trap play” during the Colts’ final sequence of plays, with Colt linemen – Art Spinney (63) making trap block on Giant tackle, Dick Modzelewski (77), and George Preas (60) on Giant linebacker Sam Huff (70) – clearing the way for Colt fullback, Alan Ameche (35).

The next play was a run by Dupre who was stopped cold by the Giant’s line for no gain. Unitas then threw a pass to Raymond Berry who ran a slant pattern over the middle for a gain of 11 yards, bringing the Colts to the Giant’s eight yard-line. The Colts then had first-down-and-goal-to-go.

However, at this point, in the middle of Raymond Berry’s catch, millions of TV viewers across the nation no doubt went apoplectic as the TV transmission of the game suddenly went black. Someone in the crowd had knocked a cable loose in the end zone. NBC tried to get a delay in the game, but failed initially. Then, after some “drunk” (or instructed NBC employee) wandered onto the playing field, a timeout was called, during which NBC managed to reconnect its cable. Viewers would miss a play or two, including play no.11 in the Colt’s drive, when Ameche ran for a one yard gain.

Colt receiver, Ray Berry, making one of his catches during 1958 Championship Game. Berry's 12 receptions for 178 yards that day set an NFL record that stood for 55 years.

On the next play the Giant defenders dug in on the goal line, including linebacker Sam Huff, all expecting a run. Fullback Ameche got the call, put his head down and sailed through a big opening off right tackle and into the endzone. Colts win, game over! Final score, Colts 23, Giants 17.

Headlines from The Salisbury Times in Maryland reporting on fan reaction to Colt's victory.

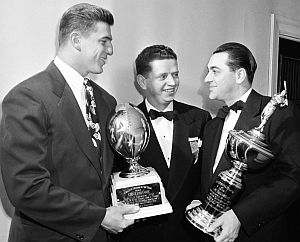

Back in Baltimore there was wild celebration; 30,000 fans would come out to the airport back home to greet their conquering heroes. Some newspaper stories ran a front-page photo of one happy Colt threesome in the locker room – Steve Myhra, Johnny Unitas, and Alan Ameche.

Unitas was the MVP of that game, awarded for his stellar late-game and sudden-death heroics, as he completed 26 of 40 passes for 349 yards, then a championship game record. Raymond Berry’s 12 receptions for 178 yards and a touchdown that day also set a championship game record that would stand for 55 years.

The following year, Unitas, Berry, and the Colts returned to win the 1959 NFL championship game, also against the New York Giants. But it was the 1958 game that would live for the ages.

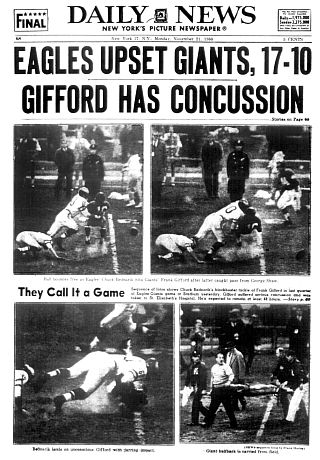

New York Daily News, Monday, December 29, 1958 edition, announcing Colts win with photograph of Colt fullback Alan Ameche scoring winning touchdown behind great Colt blocking.

In fact, “greatest game” accolades for the 1958 NFL Championship Game began almost immediately. In the Monday morning edition of the New York Daily News following the game, reporter Gene Ward wrote:

“In years to come when our children’s children are listening to stories about football, they’ll be told about the greatest game ever played – the one between the Giants and Colts for the 1958 NFL Championship.”

They’ll be told of heroics the like of which never had been seen . . . of New York’s slashing two-touchdown rally to a 17-14 lead . . . of Baltimore’s knot-tying field goal seven seconds from the end of regulation playing time . . . and, finally, of the bitter collapse of the magnificent Giant defense as the Colts slammed and slung their way to a 23-17 triumph with an 80-yard touchdown drive in the first sudden death period ever played….”

True enough; the game was an emotional roller coaster, with ups and downs, multiple lead changes, exciting plays, costly miscues, player heroics, and more. But “greatest” and “best” game attributions would come from other quarters as well, including an early boost from Sports Illustrated magazine, then and now, a respected journal of sports reporting and analysis.

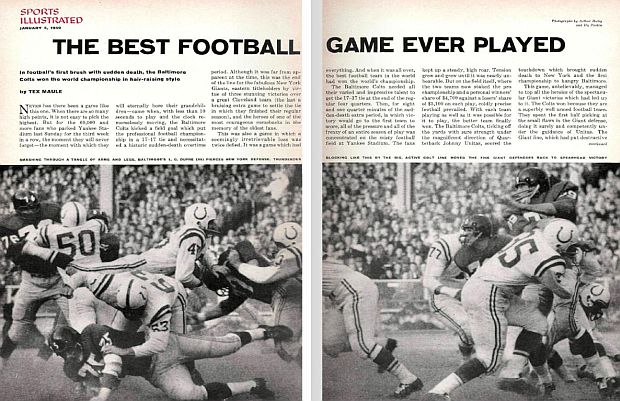

Only a week or so after the game was played, a January 5th, 1959 Sports Illustrated story by Tex Mule was titled, “The Best Football Game Ever Played.” This piece ran over five pages with several photographs by Arthur Daley and Hy Peskin. The first two-page spread from that piece is shown below. Maule, in his article, would say that the contest “was a truly epic game which inflamed the imagination of a national audience.”

The January 5th, 1959 issue of “Sports Illustrated” lauds the 1958 NFL Championship Game as “The Best Football Game Ever Played” in a five-page story by Tex Maule with photos by Arthur Daley and Hy Peskin. Click for magazine issue.

But Sports Illustrated wasn’t finished with just one piece on the game. Two weeks later, the magazine followed up in its January 19th, 1959 edition with a more detailed breakdown of the game by Tex Maule, along with dramatic hand drawings by Robert Riger, and some play diagrams and description, recreating some of game’s action in detail. That article was titled, “Here’s Why It Was The Greatest Game Ever.” A sampling of a two-page layout from that piece is offered below, but the full Sports Illustrated treatment of the game in this edition ran for nine pages, with drawings and annotation, including one page with a diagram of a football playing field marking the on-field progress of each of the 13 plays Johnny Unitas called in the final Colt drive in the sudden death period.

Sports Illustrated, January 19th, 1959, showing first two pages of a nine-page spread of diagrams, play calling, and analysis of the December 28, 1958 NFL championship game between NY Giants and Baltimore Colts. Click for magazine issue.

Some observers believe that the January 1959 Sports Illustrated pieces did capture a sense of what the game meant to those who were there at the time or had viewed in on TV, and also how the culture then began perceiving pro football. But the legend and lore for the 1958 game only grew thereafter, especially as the years went by. In fact, over the next fifty years, this game would become the subject of a number of books, magazine features, film documentaries, player reunion TV shows, and more.

The first of the books on the 1958 game came nearly 20 years later, in 1976 – The Game of Their Lives, by Dave Klein, a sports writer for the Newark Star-Ledger (New Jersey). Published by Random House, this book profiled the 13 players from the 1958 game who would later be inducted into the pro football Hall of Fame. A paperback edition of this book came out a year later, and it was also re-issued in digital and paperback form again in 2007-2008.

But after Klein’s book came out in 1976, there wasn’t much more activity on books about the 1958 game until about the time of its 50th anniversary in 2007-2008 (click on book covers at right for Amazon.com).

In April 2008, Sports Illustrated put the 1958 game on its cover, using the classic photo of Unitas rearing back in QB form preparing to throw one of his passes during the game, and titling its lead feature story, “The Best Game Ever,” as it had nearly 50 years before in January 1959. Only this time, the feature story was written by book author, Mark Bowden, and titled: “How John Unitas and Raymond Berry Invented the Modern NFL.”

Bowden would also publish his own book on the game in 2008, The Best Game Ever: Giants vs. Colts, 1958, and The Birth of The Modern NFL.

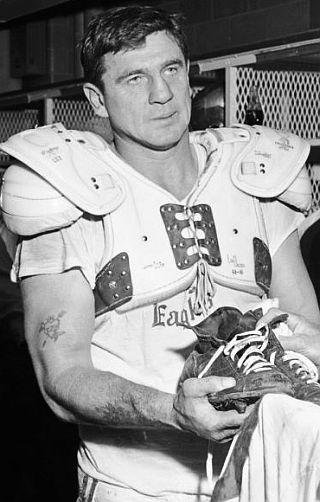

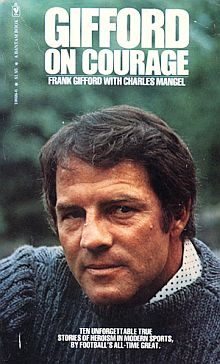

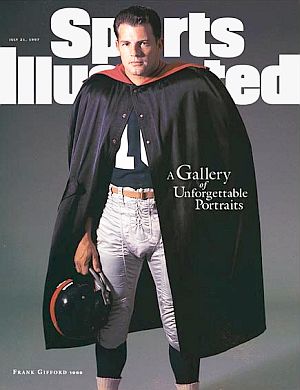

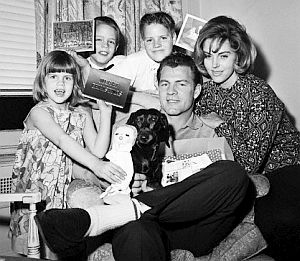

Frank Gifford, meanwhile, a former New York Giant player in the 1958 game, and also by this time, a well-known sportscasting celebrity who had worked on TV’s Monday Night Football games, also wrote a book on the 1958 game that came out in November 2008. This book – The Glory Game: How the 1958 NFL Championship Changed Football Forever – was written with Peter Richmond, and was popular at the time of the game’s 50th anniversary.

The genesis of the Gifford book had begun with Pulitzer Prize winning writer David Halberstam – famous for his book on Vietnam, The Best and the Brightest, and others, including several sports books. Halberstam had intended to write a book on the 1958 game and Gifford was recruited to help Halberstam get in touch with a number of the players from that game for the planned book. Halberstam, however, on his way to meet one of his first interview subjects for that book, was killed in a California car accident. Thereafter, Gifford decided to take on the project. And once the book came out, Gifford made the rounds on some sports shows and media interviews talking about the famous game.

There were also a couple of other books that came out at that time. In September 2008, Lou Sahadi, an author of other sports and pro football books, published One Sunday in December: The 1958 NFL Championship Game and How It Changed Professional Football, released by Lyons Press. And also that year, the Professional Football Researchers Association issued a book titled, The 1958 Baltimore Colts: Profiles of the NFL’s First Sudden Death Champions.

|

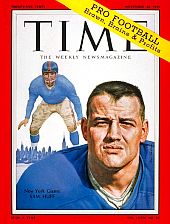

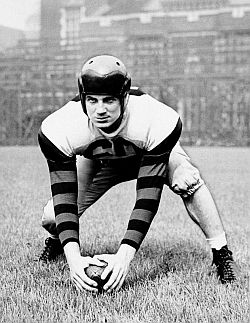

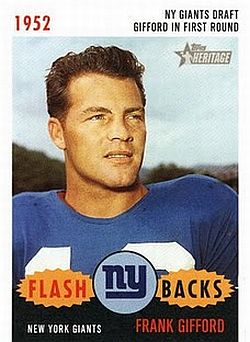

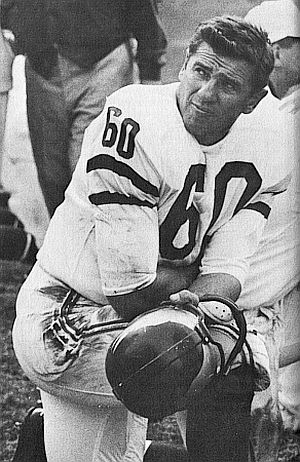

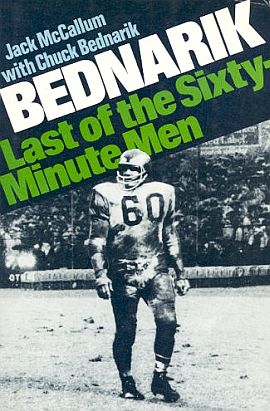

“Famous Players” The 1958 game also became known for its famous players – those who entered the professional Football Hall of Fame and others who were famous in that game, for what they did elsewhere in football, and/or for later achievement in sportscasting and other career endeavors. What follows below are brief profiles of selected Colt and Giant players who took part in the famous 1958 NFL Championship Game (some with links to their books at Amazon.com). – Baltimore Colts – Alan Ameche, cousin of actor Don Ameche, won the Heisman Trophy in college at the University of Wisconsin where he played both fullback and linebacker. He is one of six Wisconsin players to have his numeral retired there. Nicknamed “The Horse,” and famous for his winning touchdown in the 1958 NFL Championship game, Ameche was elected to the Pro Bowl in his first four seasons in the NFL.Due to an Achilles tendon injury in 1960, Ameche finished his NFL career after six seasons with 4,045 rushing yards, 101 receptions for 733 yards, and 44 touchdowns. He is one of four players named to the NFL 1950s All-Decade Team not elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame. Ameche was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame in 1975 and the Rose Bowl Hall of Fame in 2004. Along with Colts teammate Gino Marchetti, Ameche founded the Gino’s Hamburgers chain and the Baltimore-based Ameche’s Drive-In restaurants were also named for him. Raymond Berry was a split end for the Baltimore Colts from 1955 to 1967. When he was drafted in the late rounds by the Colts in 1954 he was considered a long shot to make the team. His college career at SMU had not been exceptional and he had poor eyesight. However, his subsequent rise with the Colts has been touted as one of American football’s Cinderella stories. He became known for rigorous practice and attention to detail, along with running near-perfect pass routes and his sure handedness. By his second NFL season, after quarterback Johnny Unitas arrived, Berry’s talents came in full display. Over the next 12 seasons together, the two became one of the most dominant passing and catching duos in NFL history. Berry, who did not miss a single game until his eighth year in the league, led the NFL in receptions and receiving yards three times and in receiving touchdowns twice. When his playing days ended, Berry began coaching. After several assistant coaching positions, he became head coach of the New England Patriots from 1984 to 1989. In 1973, Berry was voted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in Canton, Ohio. He is also a member of the NFL 75th Anniversary All-Time Team, compiled in 1994, and the 1950s All-Decade Team. Berry’s No. 82 jersey is retired by the Colts and he is also included in the Baltimore Ravens Ring of Honor. Art Donovan, a Colt defensive lineman, was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1968. As a U.S. Marine he served in the Pacific Theater during World War II seeing action in the Battle of Luzon and the Battle of Iwo Jima. He played his college football at Boston College following his military service. He was an All-NFL selection 1954-1958 and played in five straight Pro Bowls. During his playing days Donovan was noted as a jovial and humorous teammate and capitalized on those qualities with television and speaking appearances in later years. He appeared ten times on the Late Show with David Letterman telling humorous stories about his playing days and “old school” footballers. Donovan also made other TV guest appearances and was a guest commentator for the WWF’s 1994 edition of “King of the Ring.” He was also co-host of the popular 1990s Baltimore TV program, “Braase, Donovan, Davis and Fans,” with fellow Colt teammate Ordell Braase. Donovan also owned and managed a country club in Towson, Maryland and he published his autobiography in 1987 titled, Fatso. Art Donovan died in 2013 from a respiratory disease at age 89. Eugene Allen Lipscomb, also known as “Big Daddy” due to his hulking 6′-6″/285 lb. size, was born in Uniontown, Alabama. He never knew his father, moved to Detroit at age three, where his mother was brutally murdered when he was 11, then raised by his grandparents. For a time at Detroit’s Miller High School, he starred in football and basketball, but was declared ineligible his senior year for playing semi-pro basketball. He then enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps, playing football for the Camp Pendleton team. He was signed as a free agent by the Los Angeles Rams (1953-1955) before being traded to the Baltimore Colts where he played five seasons. In 1958 and 1959, he earned a spot in the Pro Bowl, and was instrumental in the Colts’ two consecutive NFL Championships in 1958 and 1959. He then went on to play for the Pittsburgh Steelers for two seasons. Fellow players described him as a powerful big man with unusual speed and athletic ability, but also as a gentle and big-hearted person off the field, often helpful to those down-and-out. Gino Marchetti, his teammate and mentor, found his lateral movement exceptional, calling him “our fourth linebacker;” an uncommon defensive tackle who could sometimes catch halfbacks downfield. In his final game, the 1963 Pro Bowl, Lipscomb was named MVP after making 11 tackles, forcing two fumbles and deflecting a pass. But Gene Lipscomb also had a fondness for nightlife, women, and liquor, and in May 10, 1963, he was found dead of a heroin overdose in Baltimore, though many believed he was not a drug user and suspected foul play. He was 31 years old. In Baltimore, 30,000 lined up for his funeral. Several magazines would later profile and eulogize him following his death (see Sources). Gino Marchetti, the son of Italian immigrants, enlisted in the U.S. Army during World War II and fought in the Battle of the Bulge as a machine gunner. After playing college football at the University of San Francisco, he was drafted by the New York Yanks, the team that later became the Baltimore Colts. Marchetti played 13 seasons with the Colts and became known as a relentless pass-rusher. He was voted “the greatest defensive end in pro football history” by the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1972. In 1999, he was ranked number 15 on The Sporting News list of the 100 Greatest Football Players, then the second-highest-ranking defensive end behind Deacon Jones.In 1959, Marchetti joined with several of his teammates, including Alan Ameche, and opened a fast food restaurant. The business grew, began to franchise, and would eventually become known as Gino’s Hamburgers, a popular fast food chain in the 1960s. On the East Coast in would grow to have 313 company-owned locations when the chain was sold to Marriott International in 1982 and became Roy Rogers restaurants. Lenny Moore, Penn State standout from Reading, Pennsylvania, won the NFL Rookie of the Year as a Baltimore Colt running back in 1956. In 1958, he caught a career-high 50 passes for 938 yards and seven touchdowns in helping the Colts win the NFL championship. In 1959, he had 47 receptions for 846 yards and six touchdowns as the Colts repeated as champions.In 1964, Moore had one of his best seasons when he scored 20 touchdowns, helping the Colts to a 12–2 record and another trip to the NFL Championship Game. He was voted MVP by his fellow players that year and also won the Comeback Player of the Year Award. Moore was selected to the Pro Bowl seven times and was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1975. In 2005, he published his autobiography, All Things Being Equal. In 2010, Moore retired from the Maryland Department of Juvenile Services after 26 years of service, working with at-risk kids in Maryland middle schools and high schools. Jim Parker, offensive lineman with the Baltimore Colts from 1957 to 1967, played college football at Ohio State University from 1954 to 1956. During the 1958 Championship Game, Sam Huff noted that the Giant’s All-Pro defensive end, Andy Robustelli, was having no success getting past Parker to harass Unitas. Huff recalled: “Andy couldn’t get around Parker; he couldn’t come under him; he couldn’t go over him. The immovable object, that’s what Jim Parker was.” And Robustelli himself would say: “I used to think there wasn’t a big tackle I couldn’t outmaneuver. But Parker was too strong, too smart, too good.” Parker was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1973 and the College Football Hall of Fame in 1974. He is considered among the greatest lineman to ever play pro football. In 1994, Parker was selected to the NFL 75th Anniversary All-Time Team. In 1999, he was ranked number 24 on The Sporting News list of the 100 Greatest Football Players. Jim Parker died in 2005 at the age of 71. Johnny Unitas, legendary quarterback of the Baltimore Colts, grew up in the Mount Washington neighborhood of Pittsburgh, PA, losing his father at age 5 and raised by his mother, who worked two jobs to make ends meet. Of Lithuanian decent, Unitas played halfback and quarterback at Pittsburgh’s St. Justin’s High School, and dreamed of playing at Notre Dame, but at a try out there he was told by coach Frank Leahy he was too skinny and would “get murdered” on the field. Unitas played instead for the University of Louisville, where mid-career there, the school deemphasized football, but Unitas persisted, playing both ways, heroically in a few cases, suffering many losing contests. Still, Unitas emerged from Louisville with 245 completed passes for 3,139 yards and 27 touchdowns and was selected as a ninth-round draft pick by the Pittsburgh Steelers in 1955. However, with four other QBs in training camp, Unitas was cut by the Steelers even before training camp had ended. After being cut, Unitas played for the Bloomfield Rams in the semi-pro Greater Pittsburgh League. In 1956, Baltimore Colts coach Weeb Ewbank gave Unitas a look and liked what he saw and signed him for a pittance. But with the Colts, Unitas would become the prototype, modern era marquee quarterback, setting records and winning NFL most valuable player awards in 1959, 1964, and 1967. For 52 years he held the record for most consecutive games with a touchdown pass ( 47, set between 1956 and 1960), until quarterback Drew Brees broke the record in 2012. Unitas is 7th all time in number of regular season games won by an NFL starting quarterback with 118. He was voted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1979. In 2004, The Sporting News ranked Unitas No. 1 among the NFL’s 50 Greatest Quarterbacks, with Joe Montana at No. 2. At the Baltimore Ravens stadium a statue of Unitas is the centerpiece in the stadium’s front plaza, and large banners depicting Unitas in his heyday flank the entrance. Towson University named its football and lacrosse complex Johnny Unitas Stadium in recognition of his football career and his service to the university.– New York Giants – Roosevelt “Rosey” Brown, growing up in Charlottesville, VA, initially played trombone in the Jefferson High School band. He was forbidden to play football by his family after his older brother died from a football injury. However, Brown did play at the prodding of the high school coach, and at first without his father’s knowledge. He then went on to Morgan State University on a football scholarship where he would be named to the Pittsburgh Courier’s All-America team in 1952. Brown was selected by the New York Giants in the late rounds of the 1953 NFL draft, would become one of the team’s most consistent and valuable players, appearing in 162 games, missing only four games in a 13-year career. In his prime, between 1956 and 1963, he helped lead the Giants to six division championships and the 1956 NFL Championship Game. He was selected as a first-team All-NFL player eight consecutive years and was also selected to play in the Pro Bowl nine times. After his playing days, Brown became the Giant’s assistant offensive line coach in 1966, then offensive line coach in 1969. He remained with the Giants organization in the scouting department for many years. Rosey Brown was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1974. In 1999, he was ranked number 57 on The Sporting News list of the 100 Greatest Football Players. Brown passed away in 2004. Charlie Conerly, quarterback for the New York Giants from 1948 through 1961, played college football at the University of Mississippi where he started in 1942 but left to join the U.S. Marines during WWII, and fought in the Battle of Guam in the South Pacific. Back at Mississippi in 1946, he would lead Ole Miss to their first SEC championship in 1947. That season, he also led the nation in pass completions with 133, rushed for nine touchdowns, passed for 18 more, and was a consensus All-American. Conerly was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame in 1966. The Conerly Trophy is given annually to the top college player in the State of Mississippi. Conerly also portrayed the “Marlboro Man” in cigarette commercials. After his playing days, Conerly owned shoe stores throughout the Mississippi Delta, and his wife, Perian, a sports columnist, authored the book, Backseat Quarterback. Charlie Conerly retired to his Clarksdale, Mississippi hometown where he spent his final days before his death in 1996. Frank Gifford was a star football player at the University of Southern California and was drafted by the New York Giants in 1952 as a first-round pick, 11th overall. Gifford became a versatile player for the Giants, adept at running, passing, and receiving. He also played defensive back and returned punts and kickoffs. He was named the NFL’s MVP in 1956, helping lead the Giants to a championship. Gifford was named All-NFL six times in his career and selected to a total of eight Pro Bowls at three different positions – defensive back, halfback, and flanker. Overall, Gifford spent 12 seasons with the Giants compiling a record of 3,609 yards rushing and 34 touchdowns on 840 carries. He also had 5,434 receiving yards with 367 catches and 43 touchdowns. Gifford was elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame 1977. He also became one of the better-known American sportscasters in the latter part of the 20th century, notably for ABC’s Monday Night Football (1971-1997). Gifford also had an extensive advertising career, both as a player and for years thereafter. At his death in 2015, the much admired Gifford was called “the Mickey Mantle of the Giants.” The New York Post’s Steve Serby also wrote of Gifford at that time: “He was the Giants’ first made-for-television superstar in the grainy, black-and-white glory days of the 1950s, every bit the heartthrob Joe Namath would be in the 1960s…” More detail about Gifford at this website can be found at “Celebrity Gifford” and “Bednarik-Gifford Lore.” Roosevelt “Rosey” Grier played his college football at Penn State, and was drafted by the New York Giants in 1955 as the 31st overall pick. He played with the Giants from 1955 to 1962 and was named All-Pro at defensive tackle in 1956 and 1958–1962. Later traded to the Los Angeles Rams, Grier became part of the “Fearsome Foursome” along with Deacon Jones, Merlin Olsen, and Lamar Lundy, considered one of the best defensive lines in football history. After Grier’s professional sports career, he worked as a bodyguard for Robert Kennedy during the 1968 presidential campaign and was guarding Ethel Kennedy when Sirhan Sirhan assassinated Robert F. Kennedy, though Grier helped subdue Sirhan and took control of his gun during the mayhem. Beyond football, Grier hosted his own Los Angeles television show and made numerous guest appearances on other shows during the 1960s and 1970s. He also authored several books. Sam Huff was born and grew up in the No. 9 coal mining camp in Edna, West Virginia. During the Great Depression, his father and two brothers worked in the coal mines. Playing high school football, Sam Huff collected all-state honors as a lineman, and continued at the University of West Virginia, where he was an All-American in 1955. Drafted by the New York Giants in 1956, they weren’t sure where to play him until he found a home at middle linebacker, then a relatively new position – where he excelled. Huff appeared on the cover of Time magazine for a pro football feature story in November 1959, and was also the subject of an October 1960 CBS television special, “The Violent World of Sam Huff,” part of a Walter Cronkite series. Traded to the Redskins in 1964 he helped make their defense second best in 1965. An ankle injury in 1967 ended a streak of 150 consecutive games for Huff, and he retired briefly, until Vince Lombardi, then coach of the Washington Redskins, coaxed Huff out of retirement to help bring a winning season in 1969. Huff retired for good in 1970, the year he ran for the U.S. House of Representatives, though losing in the West Virginia Democratic primary. Outside of football, Huff worked in textile sales and sports marketing, but through 2012 became known as a Washington Redskin radio and TV broadcast personality with former Redskin teammate Sonny Jurgensen. Sam Huff was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1982. In 1999, he was ranked number 76 on The Sporting News list of the 100 Greatest Football Players. In 2005, Huff’s No. 75 numeral was retired by West Virginia University. Don Maynard, then in his rookie NFL season, returned punts and kickoffs for the Giants in the 1958 Championship game. However, he would become a Pro Football Hall of Fame wide receiver with the New York Jets (1960-1972). In 1965, Maynard was paired up with Jet’s rookie QB Joe Namath and had 1,218 yards with 68 receptions and 14 touchdowns. In 1967, Maynard caught 1,434 of Namath’s historic 4,007 passing yards. The receiving yards were a career-high for Maynard and led the league; he also had 71 receptions, 10 touchdowns, and averaged 20.2 yards per catch. In the 1968 season opener against Kansas City, Maynard had 200+ receiving yards for the first time in his career and passed Tommy McDonald as the active leader in receiving yards, where he remained for the next six seasons until his retirement. Maynard finished his career with 633 receptions for 11,834 yards and 88 touchdowns. His 18.7 yards per catch is the highest among those with at least 600 receptions. Maynard’s No. 13 New York Jets numeral was the second ever retired by the Jets after Namath’s. He was selected to the Pro Football Hall of fame in 1987. In his post NFL-career, Maynard worked as a math and industrial arts teacher, a salesman, and a financial planner. Andy Robustelli was drafted initially by the Los Angeles Rams but played most of his career with the New York Giants. He was a starter on the Giants defense from 1956 until his retirement following the 1964 season. Robustelli was a six-time All-Pro selection and was inducted into the Football Hall of Fame in 1971. After his playing days, Robustelli spent 1965 as a color analyst for NBC’s American Football League broadcasts. That same year he purchased Stamford-based Westheim Travel and renamed it Robustelli Travel Services, Inc. In December 1973, he was appointed director of operations for the New York Giants, essentially becoming the team’s first general manager for the next six years. In 1988, he was named Walter Camp Man of the Year, a public service and leadership award. Robustelli Travel Services, meanwhile, specializing in corporate travel management, grew into Robustelli World Travel by the time it was sold to Hogg Robinson Group in 2006. He also founded National Professional Athletes (NPA), a sports marketing business which arranged appearances by sports celebrities at corporate functions, and International Equities, which evolved into Robustelli Corporate Services. Andy Robustelli died in May 2011 from complications following surgery. He was 85 years old. Kyle Rote was a running back and receiver with the New York Giants for eleven years. He was an All-American running back at Southern Methodist University where he became one of the most celebrated collegiate football players in the country. In December 1949, in a near upset of undefeated national champs, Notre Dame, Rote ran for 115 yards, threw for 146 yards, and scored all three SMU touchdowns in a 27–20 loss. His performance was voted by the Texas Sportswriters Association as “The Outstanding Individual Performance by a Texas Athlete in the First Half of the 20th Century.” He appeared on the cover of Life magazine November 1950 in his SMU football gear in a featured story on college football. Rote, who had been runner-up for the Heisman Trophy, was the first overall selection of the 1951 NFL Draft. When Rote retired after the 1961 season, he was the Giants’ career leader in pass receptions (300), receiving yardage (4,795) and touchdown receptions (48). He was named to the Pro Bowl four times and was elected to the College Football Hall of Fame in 1964. Following his playing career, Rote was the Giants backfield coach and also a sports broadcaster for WNEW radio, NBC, and WNBC New York. He also wrote a few football books. Kyle Rote died in 2002 following surgery. He was 73 years old. “Pat” Summerall played college football from 1949 to 1951 at the University of Arkansas as defensive end, tight end, and placekicker. He graduated in 1953 majoring in Russian history. Summerall spent ten years as an NFL football player, first drafted by the Detroit Lions, traded to the Chicago Cardinals, and then the New York Giants, his last team and where he had his best year in 1959 as a kicker, with 30-for-30 extra points and 20-for-29 in field goals. Pat Summerall, however, is best known for his many years of work in the broadcast booth, along with partners such as Tom Brookshier, John Madden, and others on various TV and cable networks including CBS, FOX and ESPN, doing NFL and other sports events and special telecasts. In 1977, he was named the National Sportscaster of the Year by the National Sportscasters and Sportswriters Association and inducted into their Hall of Fame in 1994. That year, he also received the Pete Rozelle Radio-Television Award from the Pro Football Hall of Fame. He was inducted into the American Sportscasters Association Hall of Fame in 1999. The Pat Summerall Award, honoring his legacy, has been awarded to various individuals since 2006. Pat Summerall died in 2013 of cardiac arrest at age 82. Emlen Tunnell, played 14 seasons in the National Football League (NFL) as a defensive halfback and safety for the New York Giants (1948–1958) and Green Bay Packers (1959–1961). He was the first African American to play for the New York Giants and also the first to be inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame. He was named to the NFL’s 1950s All-Decade Team and was ranked No. 70 on The Sporting News list of the 100 Greatest Football Players. He was selected as a first-team All-Pro player six times and played in nine Pro Bowls. When he retired as a player, he held NFL career records for interceptions (79), interception return yards (1,282), punt returns (258), and punt return yards (2,209). After retiring as a player, Tunnell served as a special assistant coach and defensive backs coach for the New York Giants from 1963 to 1974. Born and raised in the Philadelphia area, Tunnell was a high school standout at Radnor High School. He played his college football at the University of Toledo in 1942 and University of Iowa in 1946 and 1947. He also served in the U.S. Coast Guard from 1943 to 1946. He received the Silver Lifesaving Medal for heroism in rescuing a shipmate from flames during a torpedo attack in 1944 and rescuing another shipmate who fell into the sea in 1946. In July 1975, Tunnell died from a heart attack during a Giants practice session at Pace University in Pleasantville, New York. He was 51. |

In terms of the media hype on the famous 1958 Championship game, in addition to the books mentioned above, there have also been occasional newspaper and magazine stories on the game, as well as a few TV specials. In 1998, at the game’s 40th-anniversary, the NFL conducted a teleconference with four of the Hall of Fame players from that game — Johnny Unitas and Art Donovan of the Colts, and Frank Gifford and Sam Huff of the Giants. In January 1999, at the coin toss for Super Bowl XXXIII,…On any given Sunday since 1958, there have been, and continue to be, games that are arguably better… twelve of the surviving Hall of Fame players and coaches from the 1958 game were honored. And by its 50 anniversary year in 2008, the various books had come out, followed by commentary.

So yes, over the years there has been ample analysis of, and reflection upon, the 1958 NFL Championship Game. But despite the game’s legendary claim as the “best” or “greatest” game ever played, most analysts today acknowledge a certain amount of hype and inflated worth in that claim – and some even mark the game’s lapses of sloppiness and poor execution as evidence it was not the “greatest” NFL game ever played. Indeed, on any given Sunday during pro football seasons since 1958, there have been, and continue to be, games that are arguably better, or at least equally thrilling and engaging, played with equally-talented and superb players who regularly demonstrate amazing feats of athletic dexterity and improvisation plying their craft, whether golden-armed quarterbacks, hard-nosed offensive guards, shape-shifting halfbacks, punishing middle linebackers, or ballerina-styled, sideline-dancing wide receivers.

Yet the 1958 NFL Championship Game does have a fair claim to being an important demarcation in the rise of pro football’s cultural and economic importance. Clearly, things did change after that game, as it did get the attention of the TV networks, advertising executives, journalists, and investors.Lamar Hunt, son of oil billionaire H.L. Hunt, had spent much of 1958 trying to decide whether he wanted to invest in a football team or a baseball team. But sitting in his Houston hotel room on a business trip on December 28, 1958, he watched the Colts-Giants game and the action convinced him that football was the way to go.

Hunt would proceed to stir the competitive juices of football investors across the country as he and others founded the American Football League (AFL), and in so doing, hastened expansion in the NFL.

There were 12 pro football teams in 1959, and by the beginning of the 1960 season, that number had grown to 21. The AFL-NFL wars had begun, and with them, among other things, came escalating player salaries and a growing interest among the TV networks in telecasting all pro football games.

Pete Rozelle, elected NFL Commissioner in January 1960, helped negotiate large TV contracts, deftly playing one network against the other. In late September 1961, a bill legalizing single-network television contracts by professional sports leagues was passed by Congress and signed into law by President John F. Kennedy.

Other changes were also afoot following the 1958 Colts-Giants game that would add to pro football’s rising allure. Vince Lombardi, who had been the Giants offensive coordinator, was hired by the Green Bay Packers as head coach in January 1959, starting a pro football dynasty there and raising pro football fervor in Upper Midwest America. By 1966, Lombardi’s Packers would reign victorious over Lamar Hunt’s Kansas City Chiefs in the first AFL-NFL Championship contest (Super Bowl I, though not called that at the time). The AFL and NFL would announce their merger soon thereafter, eventually yielding a pro football colossus that today counts 32 NFL teams generating more than $13 billion in annual revenue, and Super Bowl Championship games with 100 million or more TV viewers globally.Indeed, the 1958 Colts-Giants Championship Game is quaint by comparison – especially when held up against today’s modern Super Bowl, which some might conclude is an over-the-top, out-of-control media extravaganza with way out-of-proportion importance. Yet the money-making genie of professional football is long out of the bottle, and there is no going back.

* * * * * *

Additional football-related stories at this website include: “I Guarantee It” (a profile of Joe Namath, his famous prediction for Super Bowl III, his bio and pro career, and his off-the-filed activities); “Bednarik-Gifford Lore” (the respective playing careers of Chuck Bednarik and Frank Gifford, and a famous on–the-field collision between the two); “Slingin` Sammy” (career of quarterback Sammy Baugh and Washington Redskins history, 1930s-1950s); “Dutchman’s Big Day”(about Norm Van Brocklin’s single-game NFL passing record and other QBs closing in on that record; and, “Celebrity Gifford” (a detailed look at the advertising, sports broadcasting, and TV/film/radio career of Frank Gifford ). See also the “Annals of Sport” category page for other sports stories.

Thanks for visiting – and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research and writing at this website. Thank you – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

____________________________________

Date Posted: 12 January 2019

Last Update: 11 February 2024

Comments to: jackdoyle47@gmail.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Big Game, New Era: Colts vs. Giants, 1958,”

PopHistoryDig.com, January 12, 2019.

____________________________________

Football Books at Amazon.com…

Sources, Links & Additional Information

Jack Hand (Associated Press, New York), “Colts 3.5 Point Favorite Over N.Y. Giant’s Sunday,” San Mateo Times (California), December 27, 1958, p. 6.

Gene Ward, “Colts Win In Sudden Death, 23-17; Cop Title in Fifth Period After Late FG Ties Giants,” Daily News (New York), Monday, December 29, 1958, p. 44.

Joe Trimble, “Six Inches Worth $1,600 As Giff Misses First Down,” Daily News (New York), Monday, December 29, 1958, p. 44.

“’The Greatest Game Ever Played’: Colts Beat Giants in 1958 NFL Championship,” Daily News, January 13, 2015 (reprint of 1958 story).

Tex Maule, “The Best Game Ever Played,” Sports Illustrated, January 5, 1959 (photos by Arthur Daley and Hy Peskin).

Tex Maule, “Here’s Why it Was the Best Football Game Ever,” Sports Illustrated, January 19, 1959 (drawings by Robert Riger, explanations by Tex Maule).

“1958: Baltimore Colts @ New York Giants, NFL Championship Games,” Golden Football Magazine, GoldenRankings.com.

“Greatest Game Ever Played,” Pro Football Hall of Fame.

“1958 NFL Championship Game,” Wikipedia .org.

“A Man’s Game” (Sam Huff cover story), Time, November 30, 1959.

Tony Kornheiser, “Giants, Colts of 1958 Play It Again – For Laughs,” New York Times, July 8, 1978.

Shelby Strother, NFL Top 40: The Greatest Pro Football Games of All Time, 1988.

William Gildea, When the Colts Belonged to Baltimore, 1994.

Frank Litsky, “There Were Better Games; None More Important,” New York Times, December 16, 1998.

National Football League (NFL), “Historical Chronology, By Decade,” NFL.com.

William Nack, “The Ballad Of Big Daddy: Big Daddy Lipscomb, Whose Size and Speed Revolutionized the Defensive Lineman’s Position in the Late ’50s, Was a Man of Insatiable Appetites: For Women, Liquor and, Apparently, Drugs,” Sports Illustrated, January 11, 1999.

Richard Rothschild, “Sudden Death, Sudden Impact,” ChicagoTribune.com, January 24, 2001.

Richard Goldstein, “Kyle Rote, a Top Receiver For the Giants, Dies at 73,” New York Times, August 16, 2002.

Scott Calvert, “Hero for a Working-Class Town: Friends and Fans Recall John Unitas as a Gritty, Big-Hearted Man Who Perfectly Fit the City Where He Played Football for Nearly Two Decades; 1933-2002,” Baltimore Sun, September 12, 2002.

Chris McDonell, The Football Game I’ll Never Forget; 100 NFL Stars’ Stories, 2004.

Craig R. Coenen, From Sandlots To The Super Bowl: The National Football League, 1920-1967, University of Tennessee Press, 2005.

Jonathan Yardley, “Book Review, Johnny U: The Life and Times of Johnny Unitas, by Tom Callahan, Book World, Washington Post, October 22-28, 2006.

Tom Callahan, Johnny U: The Life & Times of John Unitas, 2006.

Frank Deford, “Everything On The Line: The Colts-Giants in ’58 Was a Door Between Two Eras,” SI.com, Tuesday July 17, 2007.

“The Greatest Game Ever Played – Sports Illustrated‘s Coverage of The Game,” FleerSticker.blogspot .com, December 14, 2008.

Mark Bowden, The Best Game Ever: Giants vs. Colts, 1958, and the Birth of the Modern NFL, 2008.

Frank Gifford with Peter Richmond, The Glory Game: How The 1958 NFL Championship Changed Football Forever, 2008

Jeff Miller, “Shaky Myhra Made the Kick That Mattered Most,” ESPN, December 8, 2008.

Michael MacCambridge, “Legacy of ‘The Greatest Game’ Can Be Found in What Followed,” NFL.com, December 25, 2008.

Mike Klis, “The ‘58 Classic,” The Denver Post, December 26, 2008.

Ihsan Taylor, “The Glory Game: Q&A With Frank Gifford,” New York Times, January 10, 2009.

Bill Lubinger, “Remember When … Off-Season Was Work Time for the Cleveland Browns (and all pro athletes)?,The Plain Dealer (Cleveland), May 26, 2010.

Joe Garner and Bob Costas, 100 Yards of Glory: The Greatest Moments in NFL History, 2011.

Ernie Palladino, Lombardi and Landry: How Two of Pro Football’s Greatest Coaches Launched Their Legends and Changed the Game Forever, 2011.

Dan Manoyan. Alan Ameche: The Story of ‘The Horse’, 2012.

Joe Horrigan and John Thorn (eds.), The Pro Football Hall of Fame 50th Anniversary Book: Where Greatness Lives, 2012.

Kevin Boilard, “Pat Summerall: New York Giants Kicker’s Greatest Performances with Big Blue,” BleacherReport.com, April 20, 2013.

‘Steve Serby, “‘Unforgettable’ Frank Gifford Was The Giants’ Mickey Mantle,” New York Post, August 9, 2015.

“Evolution Of The NFL Player; Creating An NFL Player: From ‘Everyman’ To ‘Superman’,” NFL.com.

https://operations.nfl.com/the-players/evolution-of-the-nfl-player/

“AFL–NFL Merger,” Wikipedia.org.

_______________________________________