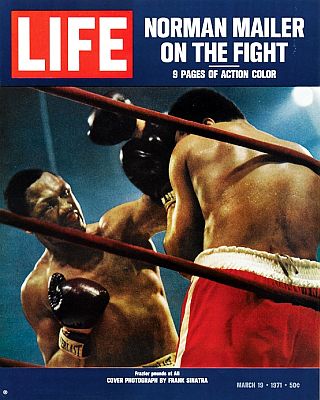

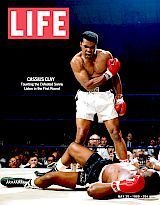

March 16th, 1971 edition of Life magazine with cover photo and feature story on the historic Joe Frazier (L) -Muhammad Ali (R) fight. Photo taken by Frank Sinatra. Click for copy.

But this fight was more than just a major boxing match for the world title. No, this match was also freighted with the social and political angst then eating at the nation — namely, civil rights and the Vietnam War.

The year was 1971. Richard Nixon was in the White House. The No. 1 songs in January and February that year were “My Sweet Lord” / “Isn’t It a Pity” by former Beatle George Harrison; “Knock Three Times” by Dawn; and “One Bad Apple” by The Osmonds. At the box office, the Hollywood film, “Love Story,” starring Ali MacGraw and Ryan O’Neal, was setting sales records as the No. 1 film through early March that year. On television, the landmark sitcom “All in the Family,” starring Carroll O’Connor as Archie Bunker, made its debut on CBS. In the Super Bowl that year, played on January 17th, Baltimore beat Dallas,16-13.

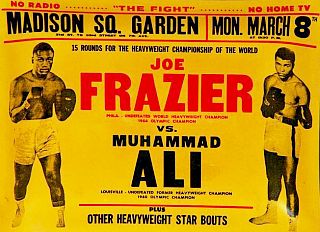

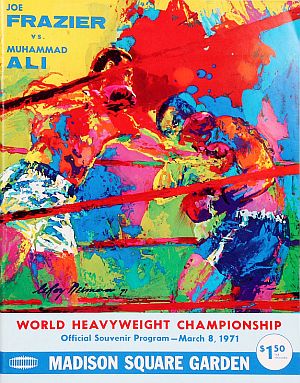

But the big event in sports in the early part of 1971 was the scheduled 15 round heavyweight boxing championship match between Joe Frazier and Muhammad Ali. That bout was set for March 8th at New York city’s Madison Square Garden. Joe Frazier, with a record of 26–0, was the reigning heavyweight champion of the world. The challenger that night was Muhammad Ali with a record of 31–0.

Poster for the March 1971 World Heavyweight Championship fight between Joe Frazier and Muhammad Ali. Click for similar poster.

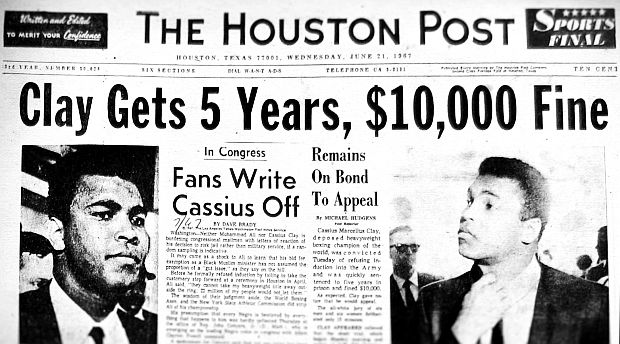

However, in March 1967, Ali had his championship title stripped away by boxing authorities for his refusal to be inducted for U.S. military service. Ali had claimed it was against his religion to participate in war. He had also made earlier public statements in 1966 on the war and why he would not go:

“Why should they ask me to put on a uniform and go ten thousand miles from home and drop bombs and bullets on brown people in Vietnam while so called Negro people in Louisville are treated like dogs and denied human rights? No, I am not going…to help murder and burn another poor nation simply to continue the domination of white slave masters of the darker people the world over…”

June 1967 Houston Post front-page headlines on the conviction of then heavyweight boxing champion, Cassius Clay /Muhammad Ali, for refusing induction into U.S. military service. He was then out on bond while his case was appealed in the courts, and in two instances – although his title and boxing license had been revoked – would gain approvals to fight in two 1970 bouts.

Ali did not fight from March 1967 to October 1970, and with two exceptions thereafter. First, by virtue of an Atlanta, Georgia judge granting him a license to fight in Atlanta, an October 1970 bout was arranged against Jerry Quarry, which Ali won in three rounds. And second, after a federal court ordered his New York boxing license reinstated, he fought December 1970 bout with Oscar Bonavena at Madison Square Garden which he also won in 15 rounds. But during this time, and through much of 1971, Ali labored under the cloud of his federal draft conviction, awaiting the outcome of his appeal. Still, with his December 1970 win over Bonavena, Ali was then the prime contender to meet Frazier in a championship bout.

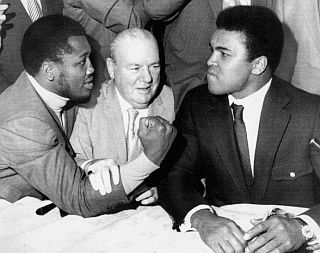

Joe Frazier and Muhammad Ali feuding for the cameras (and for real), separated by NY State Athletic Commission’s Edwin Dooley at Dec 30 1970 news conference. AP photo.

Frazier was known as a ferocious fighter with a powerful left hook. According to one account of Frazier’s decisive win over Ellis, he delivered “a frightening display of power and tenacity.” Frazier by then was recognized by boxing authorities as the World Champion. So, in the months between the scheduling of the March 1971 match with Ali – agreed to in December 1970 – and during the run up to that fight in early 1971, there was a tremendous amount of hype and anticipation as to who was the true heavyweight champ. Both Frazier and Ali were then undefeated. More on the fight in a moment.

Backstory: The Fighters

Before Muhammad Ali was Muhammad Ali, he was known as Cassius Clay, a young boxer from Louisville, Kentucky who developed a dazzling style in the ring. In 1960, as an 18 year-old, he had won the Olympic light heavyweight title. That fall, he turned pro at 18 with the backing of some Louisville businessmen. From October 1960 to June 1963, Cassius Clay won all 19 bouts he entered, a few with some difficulty, notably Doug Jones and Henry Cooper, the latter of whom knocked him down once with a left hook. And it was during these years that Ali became something of a non-stop talker, self-promoter, and boxing poet, proclaiming himself “the greatest” and often predicting in rhyme the round he would beat opponents. “Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee,” was a favorite line he used to define his light-of-foot /quick punching style, mocking all comers. The boxing world and the sports media hadn’t seen anything like him.

Yet this “Cassius Clay” fellow was attracting wide attention wherever he went, for himself and boxing.

By March 1963, he was featured on the cover of Time magazine in a rendition by artist Boris Chaliapin who sought to capture Clay’s “playful mischievousness,” portraying him as part boxing poet. Inside the magazine, Clay was profiled in a favorable five-page story.

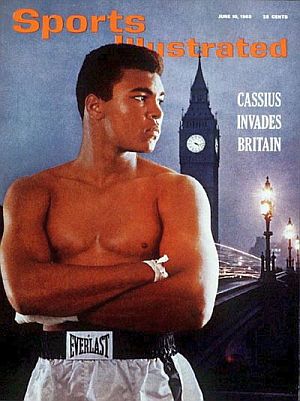

That was followed by a June 10th, 1963 Sports Illustrated cover of the young boxer tagged, “Cassius Invades Britain.” Clay was then on his way to fight Great Britain’s Henry Cooper in London.

These stories included Clay’s self-boasting quips, with Sports Illustrated tagging him “The Louisville Lip.” It was a style that would bring him media attention and endear him to many of his fans, while at the same time repulsing the conservative boxing world and his opponents, as well as many sportswriters and boxing fans.

But along with his boasts and bravado, there was real athletic ability and boxing talent. “He had incredibly fast hands and cat-like reflexes,” noted sportswriter Michael Silver. “His handsome face was rarely hit” – a point of pride he would often repeat in press conferences.

Cassius Clay also had a serious side, and was a early follower and friend of Malcolm X, then a Black Muslim. A big turning point for Clay came when he beat Sonny Liston in February 1964 to win the world heavyweight boxing crown.

After his victory over Liston, Cassius Clay denounced his “slave name” and became a Black Muslim, a little known black separatist movement that practiced the religion of Islam, advocating self help for African Americans. He soon began using his new Muslim name — Muhammad Ali. He made clear at the time he would not be treated the way that other black heavyweight champs had been treated. Some of his black opponents, including Joe Frazier, refused to call him by his new name, while the boxing establishment hoped his stay at the top of boxing would be brief.

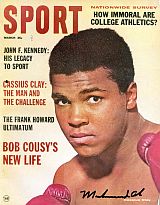

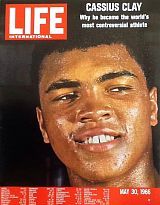

But Clay – now Muhammad Ali – became a boxing superstar following the Liston fight, as a new round of publicity elevated him to international celebrity. Life magazine put him on the cover of their magazine – not only for its domestic issue of March 6, 1964, with six pages of coverage from the Liston fight, but also in later issues using the same photo and some of the same content. Life’s international issue of May 30th, 1966, circulating in dozens of countries, ran him on the cover, as did some Life special national issues, such as its Spanish edition of July 1966. (click on covers for available copies).

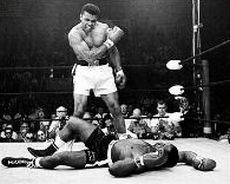

May 1965: Ali and Liston. |

|

Meanwhile, from 1965 to 1967 Ali defended his title against all comers – winning nine bouts, including a rematch with Liston in 1965, a fight that yielded the famous photo of Ali standing defiantly over a knocked down Liston.

Ali’s views on the Vietnam war, his religion and the black race were part of the territory he covered in public – and he received a degree of scorn for speaking out.

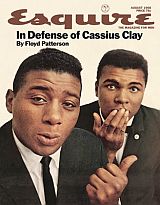

But one fighter, Floyd Patterson, who Ali had fought and beaten in November 1965 — a fighter who did not agree with Ali’s views — but nonetheless lent his name and image and support on behalf of Ali’s right to free speech in an August 1966 Esquire magazine cover and feature story. That piece was written with Gay Talese and entitled, “In Defense of Cassius Clay.” Ali’s press coverage by this time went well beyond the usual sports venues.

In the ring during these years, Ali was in a class by himself, few could touch him. But by the time he refused the call of Uncle Sam to serve in the military, the country was split right down the middle over the Vietnam War, and he became part of the controversy and polarization. In 1967, when he refused the draft, hundreds of thousands of Americans were doing service in the jungles of Vietnam. Nearly 30,000 had been killed by then. The champ was denounced as a draft dodger; congressmen vilified him, others questioned his patriotism and his motives.

Racial issues were also coming to the fore in new ways while Ali was making his stand. Racial unrest had broken out in Los Angeles in 1965; in Newark, New Jersey, Detroit, Michigan, and a dozen other cities in 1967; and in April 1968, following the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, protest and unrest occurred in more than 100 cities. The Black Power movement had begun by then as well. African American athletes at the Summer Olympics in Mexico City in 1968 had given the black power salute from the medals podium, and also that summer, the James Brown song, “Say It Loud, Say it Proud,” hit No. 1 on the R& B music chart.

April 1968: Cover of Esquire. |

|

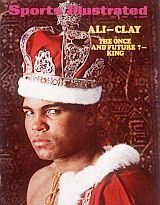

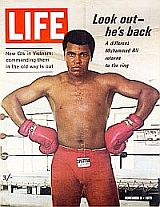

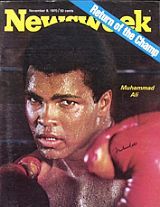

Ali, meanwhile, continued to be featured on magazine covers – for Esquire in 1968 and Sports Illustrated in May 1969. Esquire, courtesy of its art director George Lois, did a classic cover for its April 1968 issue, featuring Ali in a Saint Sebastian pose with puncturing arrows in his body, with head thrown back as if in great pain (St. Sebastian was a early Christian martyr shown in some classic paintings tied to a post and shot with multiple arrows). As George Lois would in fact explain to Ali while lobbying him for the photo shoot as an arrow-riddled martyr – “…And what I am saying is that you are a martyr to your race, you are a martyr because of the war. It’s a combination of race, religion, and war in one image, you’re symbolizing it in one image.” For the May 5, 1969 issue of Sports Illustrated Ali was depicted in a cover shot draped in royal garb complete with kingly crown as the tagline asked, “Clay-Ali: Once and Future King?.” The feature story pondered the future of the 27 year-old boxing champion, then in a kind of limbo while he appealed his conviction. Then, in 1970, when an Atlanta judge allowed him to face Jerry Quarry in his first return to the ring, his fans were ecstatic. Life and Newsweek put him on November 1970 covers. And after his fight with Quarry, he was awarded the Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Freedom Medal and Mrs. Coretta King said that he was not just a champion of boxing but “a champion of truth, peace and unity.” For his fans and admirers, Ali was carrying a lot of hopes and expectations. And this too, figured into the background leading up to the Frazier-Ali fight in March 1971.

Joe Frazier, for his part, was almost the complete opposite of Ali, quiet and hard working, not inclined toward social statement. Nor did he have the celebrity cache and media notice that Ali had accumulated. Born into a poor family on a farm in rural South Carolina, Joe Frazier was the youngest of 12 children. As a married 16 year-old in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, he worked in a slaughterhouse. That was about when he took up boxing for exercise, as he had begun to gain weight. He was discovered trying to lose weight boxing at a Philadelphia Police Athletic League gym. He soon became a recognized amateur, winning three Golden Gloves titles. In 1964, he added the Olympic heavyweight championship gold medal. Upon his return from the Olympics, however, there was no money, and he took a job as a janitor in a Baptist church of North Philadelphia. There, the pastor happened to have some wealthy friends, among them F. Bruce Baldwin, executive of the Horn & Hardart restaurant chain who helped set up financing for Frazier’s boxing career. He was 21.

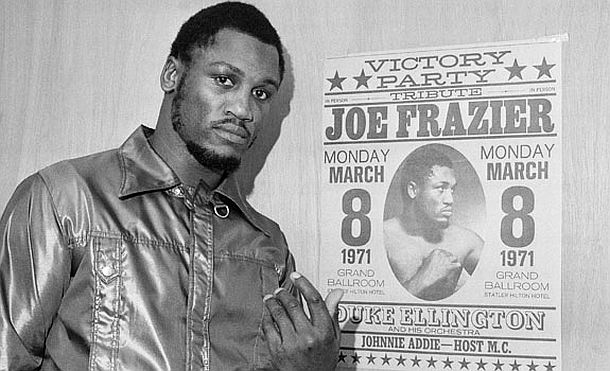

Heavyweight boxing champ, Joe Frazier, in 1971. By this time he had a 26-0 record, with 23 KOs; shown here posing by “victory party” poster after final public workout in Philadelphia, March 6, 1971. AP photo/Bill Ingraham.

Over the next five years, he compiled a fearsome record or 26 and 0, winning 23 of his bouts by knockout. In the ring Frazier developed a reputation for his devastating left hook. Boxing analysts called him “a pure puncher.” He would come at opponents relentlessly, in a low and forward moving crouch. His bobbing and weaving could sometimes disguise his left hook, that could catch opponents by surprise. Outside of the ring, Frazier was described by sportswriter Michael Silver as “a decent, hardworking, law abiding, church going family man, who was too busy trying to support his growing family to get involved in any causes.” But ahead of the famous March 1971 fight, Frazier was also drawn into the soci-political currents of the times.

January 28, 1971: Muhammad Ali, with a small crowd behind him, appears outside Joe Frazier’s gym in Philadelphia, PA to taunt him. Photo, Associated Press.

The Backdrop

Ali, as he had done with other opponents and part of his stage act and clowning for the media, would taunt Frazier incessantly. He called Frazier names – some of which cut Frazier to the quick, and for which he could never quite forgive Ali. Frazier was ignorant, said Ali at one point, and he likened him to a gorilla. He also used “chump,” “impostor,” “amateur” and “tramp” to describe him from time to time. Ali also said Frazier’s black supporters – and Frazier himself – were “Uncle Toms,” black code for being subservient and/or sucking up to the white man.

Yet, before all the name calling, Frazier had done what he could to help Ali, reportedly lending him some money during his suspension, testifying in Congress, and petitioning President Richard Nixon to have Ali’s boxing license reinstated. Ali, in fact, had come to Frazier, seeking help to get his license back. Among other things, he told Frazier that once reinstated, an Ali-Frazier match would make them both rich. As Frazier would later recount to Sports Illustrated: “He’d come to the gym and call me on the telephone. He just wanted to work with me for the publicity so he could get his license back. One time, after the Ellis fight [i.e., after Feb 1970], I drove him from Philadelphia to New York City in my car. Me and him. We talked about how much we were going to make out of our fight. We were laughin’ and havin’ fun. We were friends, we were great friends. I said, ‘Why not? Come on, man, let’s do it!’ He was a brother. He called me Joe, ‘Hey, Smokin’ Joe!’ In New York we were gonna put on this commotion.”

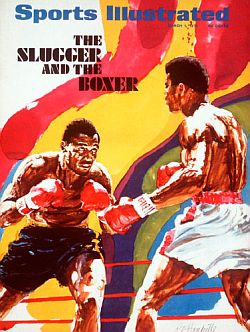

March 1st, 1971. Colorful pre-fight edition of Sports Illustrated, with Ali-Frazier cover art by artist Robert Handville. Click for copy.

…The fight was about much more than two men dueling for the undisputed world heavyweight crown. It was about two men representing vastly different versions of our nation in turmoil. With American troops still waging a lost war in Southeast Asia, Ali symbolized a strong challenge to the status quo while Frazier was seen by many as the embodiment of those who were clinging to the past. No doubt these perceptions were way too simplistic, and unfair, especially to Frazier, but they were another example of how much the country was looking for a way to define itself, and its future.

In the boxing world too, the anti-Ali crowd had found their man in Frazier, even though he was not keen on being anyone’s symbol or cause célèbre. Frazier was content to be himself and nothing more. “I often felt bad for Joe,” photographer John Shearer would tell Life.com in later years, recalling the weeks and months he spent with both fighters before the March 1971 bout. “He was completely miscast as the bad guy in the fight. In so many of the pictures I made of him that winter, when he’s with friends and relaxed, there’s something genuinely charming there — but something in his face suggests that if you scratched the surface, you’d find a world of other feelings.”

Meanwhile, breathing fire into the upcoming March 1971 showdown between the two fighters was the media coverage and the hype of fight promoters.

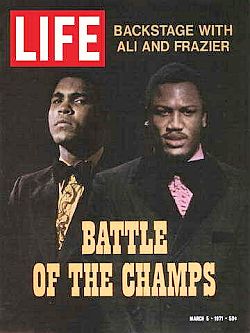

Mainstream magazines such as Life and Time had run cover stories featuring the fighters the week prior to the bout. Life ran its feature story on March 5th with the cover tagline, “Battle of the Champs,” with the fighters shown on the cover decked out in handsome formal wear. Life’s ten-page feature story by Thomas Thompson, “The Battle of the Undefeated Giants,” included photos of both the fighters by Life photographer John Shearer showing them in training and other contexts.

Thompson’s piece included background on, and quotes from, each fighter. Ali, in keeping with his loquacious ways, did not disappoint, telling Thompson at one point: “There’s not a man alive who can whup me. I’m too fast… I’m too smart… I ‘m too pretty…I am the greatest. I am the king.”

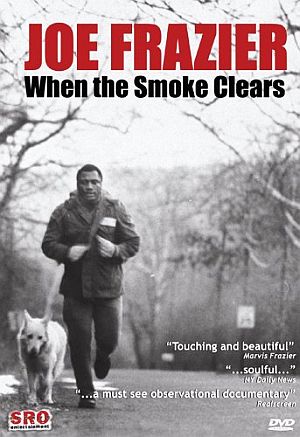

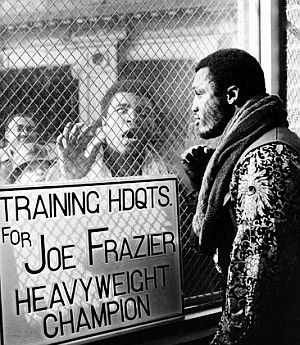

Of Frazier, Thompson wrote: “There is a confidence bordering on serenity about Frazier.” His article noted that Frazier was a religious man, read the Bible regularly, and showed him in one photo at a church service with his son Marvis. Another showed him on his daily 6 a.m., six-mile training run with his dog at his training camp, and also noted Frazier’s stage presence and more friendly nature working with his soul and R&B singing group, “Joe Frazier & The Knockouts.”

Time magazine’s pre-fight edition of March 8th, 1971 included an artist’s rendering of the two fighters’ faces on the cover beneath the tagline, “The $5,000,000 Fighters,” alluding to the $2.5 million guaranteed each fighter for their meeting at Madison Square Garden (at the time, the most money ever paid to anyone for a few hours of work). Even though Ali and Frazier were highlighted for the money they would make, the promoter of the fight, then 40 year-old Jerry Perenchio, a California theatrical agent whose clients included Richard Burton, Any Williams, Johnny Mathis, and Henry Mancini, would wind up with even more money – something on the order of $20 million to $30 million. Closed-circuit TV venues were set for 350 locations in the U.S. accommodating some 1.7 million viewers at $10 to $30 per seat. (Still, given Ali’s conviction on draft evasion charges, there were more than 20 venues that opted out of the closed-circuit offering). More viewers would come from overseas locations. Perenchio also had the rights to the souvenir fight program, commercials, poster, and post-fight film. And finally, he also had plans to acquire for auction the trunks and boxing gloves used by Ali and Frazier during the fight. “If they can sell Judy Garland’s red Oz shoes [worn in the classic 1939 Wizard of Oz film] for $15,000,” Perenchio told Life magazine in March 1971, “then we should get at least as much for these.”

Joe Frazier during a break in training prior to the March 1971 title bout with Muhammad Ali.

…Clay can keep that pretty head, I don’t want it. What I’m going to do is try to pull them kidneys out. I’m going to be at where he lives—in the body. Then I’ll be in business, when I get smoking around the body. Watch him—he’ll be snatching his pretty head back and I’ll let him keep it. Until about the third or fourth round, and then there’ll be a difference. He won’t be able to take it to the body no more. Now he’ll start snatching his sore body away, and then the head will be leaning in. That’s when I’ll take his head, but then it won’t be pretty, or maybe he just won’t care.

One tidbit of political history that occurred on the night of the Ali-Frazier fight, though little-noticed at the time, was a most-significant break-in at FBI offices in Media, Pennsylvania (and in fact, the nation’s preoccupation with the fight that night proved a helpful diversion to the burglers). A small group of independent activists known as The Citizens’ Commission to Investigate the FBI, would remove suitcases-full of FBI files later distributed to selected press revealing the agency’s spying on American citizens and a lot more. Back in New York, meanwhile, in the main arena of Madison Square Garden, the big show was about to begin.

Garden Glitterati

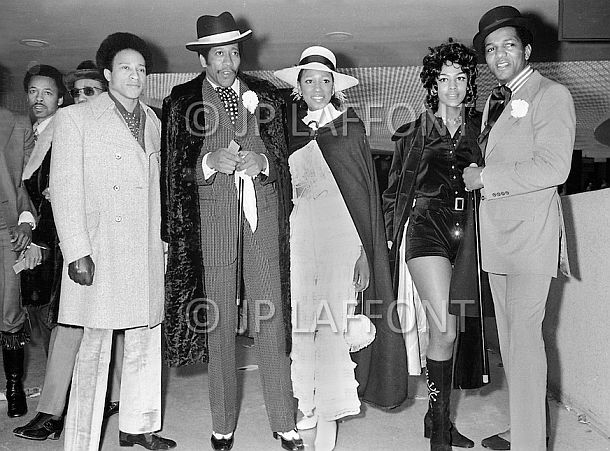

On fight night, Madison Square Garden was full of the rich, famous and fashionable. Professional championship boxing matches in those years were still something of big social events where the literati and glitterati of all stripes came out to be part of the scene. African-American boxing fans attended the event wearing the latest fashions of the day, including long fur coats and top hats for some of the guys, and the latest mini fashion for the ladies.

Photograph by famous New York photojournalist Jean-Pierre Laffont, capturing the style and high fashion of some of those attending the Joe Frazier-Muhammad Ali championship fight at Madison Square Garden, NY, March 8, 1971.

Among notables in attendance at the Garden that night were: jazz musician Miles Davis, comedian Bill Cosby, singer Diana Ross, and actors Dustin Hoffman, Diane Keaton and Woody Allen. Bob Dylan was there too, and so were U.S. Senators Ted Kennedy and Hubert Humphrey. Artist LeRoy Neiman was there; he painted Ali and Frazier as they fought. Actor Burt Lancaster was positioned at ringside, serving as a commentator on the closed circuit TV coverage. Barbi Benton and Hugh Hefner came together. Eunice Shriver was there, and so was Hollywood dancer, Gene Kelly. Bert Sugar, boxing historian and commentator was there, as was future contender George Foreman, who would later fight both Frazier and Ali.

Frank Sinatra 1, Ali-Frazier fight, 8 March 1971. |

Frank Sinatra 2, Ali-Frazier fight, 8 March 1971. |

Celebrity Frank

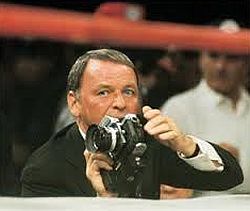

Another celebrity that figures into this story is Frank Sinatra. The famous singer and Hollywood actor was then known for his 1969 hit song, “My Way,” which had reached the Top 40 in the U.S. and did even better in the U.K. However, by early 1971 Sinatra was also talking retirement, possibly by June, after he completed a charity event (for more on Sinatra see “Sinatra Stories”). But Sinatra was also a boxing fan and an amateur photographer of sorts.

That March of 1971, Sinatra was keen to get a ringside seat for the Ali-Frazier fight, but few were available. One report had it that he made a deal with Life magazine to do some photography for the magazine at the Ali-Frazier fight, which would give him more or less free license to roam around up close to the action. But in the introduction to Life’s March 16th, 1971 edition reporting on the fight, managing editor Ralph Graves explained in an “editor’s note” column how the magazine came to use both Sinatra and writer Norman Mailer beyond its own reporters and photographers. On Sinatra’s role, Graves explained: “…We didn’t expect to get anything the professional photographers didn’t have, but [his photographs] might be worth inspecting. Indeed, Sinatra wound up getting the cover, a memorable full-spread picture [inside the magazine], and two other shots in our story….”

On the Life cover of that March 16th, 1971 edition, shown at the top of this article, there was a special credit line at the very bottom which read: “Cover Photograph By Frank Sinatra.” So, not only did this edition of Life magazine have the value of the Ali-Frazier sports celebrity as a selling point, it also had the added cache of Sinatra’s involvement and Norman Mailer’s prose. Sinatra took photos throughout the night, as others took photos of him doing his work. He became as much a diversion for some fans and news photographers as did the main contenders. Or as one observer would later put it, “Frank Sinatra was the third most photographed person that night.” Mailer’s reporting and Sinatra’s photos – at least four of the latter – would appear together in Life magazine’s nine-page spread on the fight.

March 8, 1971, Madison Square Garden, NY, NY: Frank Sinatra, on assignment with Life magazine to cover the Joe Frazier-Muhammad Ali World Heavyweight Championship fight, is a popular subject himself, as others snap away.

March 1971: Actors Paul Newman and Glenn Ford viewed the fight via closed-circuit TV in Beverly Hills, CA.

Millions more – celebrities among them – watched on closed-circuit screens across the U.S. and around the world. Actors Paul Newman and Glen Ford (pictured at right) viewed the fight at a closed circuit screening in Beverly Hills. Elvis and Priscilla Presley did the same at Ellis Auditorium in Memphis, Tennessee.

It was estimated that 300 million people around the globe had watched the fight. It was the largest audience ever for a television broadcast up to that time. In fact, more people had tuned into the fight than had watched the moon landing two years before.

In the lead up to the fight, Sports Illustrated had a featured cover story on its pre-fight edition titled, “The Slugger and The Boxer” (shown earlier above), which included some famous bouts from history, but for the current fight, described Ali as “a superb boxer” who was also “a mighty good puncher.” And in Joe Frazier, the magazine found “the very model of the relentlessly oncoming slugger.” The fight, said Sports Illustrated’s Martin Kane, “will surely rank with the classics.”

At the time of the fight, Frazier was 27 years old and at his boxing peak, Ali was 29, emerging from his legal battles, with two recent bouts under his belt. The odds makers had given Frazier a slight edge.

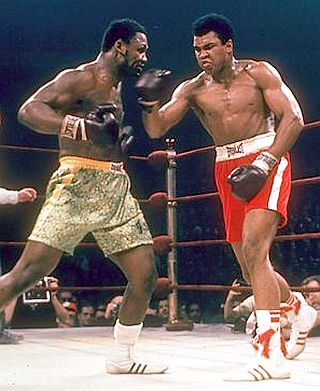

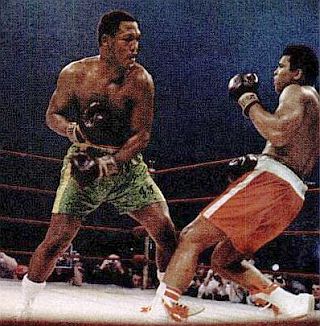

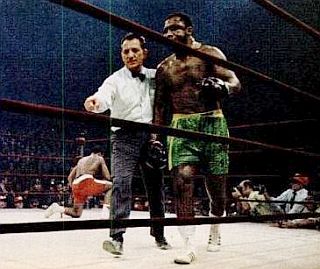

March 1971: Joe Frazier (green trunks) and Muhammad Ali (red trunks), square off in the big fight.

The Fight

At the opening bell of the scheduled 15-round fight, it was Ali who came out on the attack, dominating much of the first three rounds. He came at Frazier with a series of repeated short jabs to the face, which took their toll on Frazier over the course of the bout. Frazier’s face had visible welts by the time Round 3 ended. However, in the closing seconds of round three, Frazier hit Ali hard with hook to the jaw, as some photos caught Ali’s head snapping back.

In round four, Frazier began to dominate, again catching Ali with several left hooks. He also had Ali up against the ropes, where he went to work on Ali’s body, causing him to cover up. “Frazier didn’t fight by going for the head, the way a lot of other boxers did against Ali,” Life photographer John Shearer would later note. “He went after Ali’s body the whole fight, pounding away, taking terrible blows to the head himself.”

Frank Sinatra, roaming near ringside as he took his photographs, noticed Frazier getting hit repeatedly by Ali’s jabs. “…I kept watching Frazier putting his head too far out for Ali to punch it,” he would say in a conversation with Bill Gallo, a sportswriter with The New York Daily News. “He was defying Ali, and I said to the newspaper guy next to me: ‘He may win, but if he keeps that up, he’s going to the hospital, taking all those punches’.” Still, Frazier seemed to have his plan and was sticking with it.

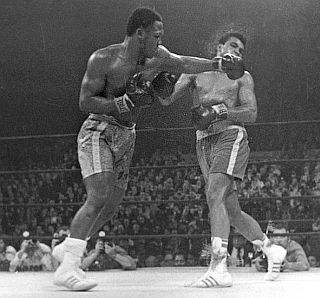

March 1971: Frazier hits Ali with a left during fight. |

Life photo showing Ali working his jabs on Frazier, which throughout the night took a toll on Frazier’s head & face. |

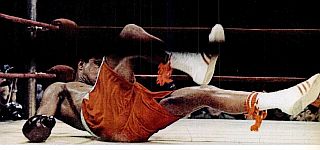

Round 15: Frazier after landing knock-down punch on Ali. |

Round 15: Ali falling to the canvass after punch by Frazier. |

Round 15: Joe Frazier escorted to his corner as Muhammad Ali recovers on the canvas following Frazier's knock-down punch. |

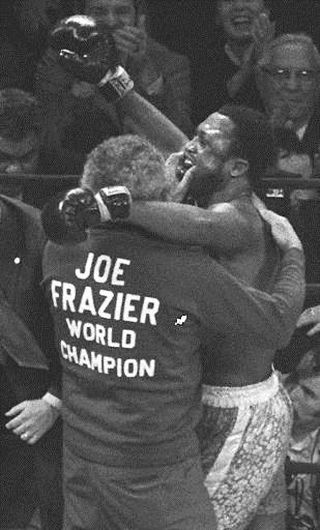

March 1971. Joe Frazier, celebrating his victory over Muhammad Ali with his corner crew. AP photo. |

“Frazier moved in with the snarl of a wolf,” Norman Mailer wrote of the middle rounds in his Life magazine piece. “His teeth seemed to show through his mouthpiece … Ali looked tired and a little depressed … At the beginning of the fifth round, he got up slowly from his stool, very slowly. Frazier was beginning to feel that the fight was his. He moved in on Ali, his hands at his side in mimicry of Ali, a street fighter mocking his opponent, and Ali tapped him with long light jabs to which Frazier stuck out his mouthpiece, a jeer of derision as if to suggest that the mouthpiece was all Ali would reach all night.”

The fight had a “grudge match” air about it; each man fighting as if he had something to prove. The verbal slurs and taunts continued back-and-forth between both fighters throughout the contest.

The sixth round came and went – the round Ali had predicted he would knock out Frazier. By this round and the next, Ali was visibly tired. The pace he had set in the earlier rounds had slowed, though he still had flurries of punches for Frazier and his speed and punch combinations kept him roughly even with Frazier,

By round eight, however, at about two minutes in, Frazier landed a clean left hook to Ali’s right jaw. At one point, as Ali tried to take refuge or on the ropes, Frazier grabbed Ali’s wrists and swung him into the center of the ring. Ali then went into a clinch with Frazier until separated by referee Mercante.

In the ninth, Frazier began to work on Ali’s body again, as Ali fended them off the best he could. But then Ali bounced back with a flurry of sharp punches and some good foot work. In the tenth Ali did well again, and it appeared the fight might be turning his way. Yet overall the fight was still very close. Then came round 11.

At about nine seconds into the round, Frazier caught Ali with a left hook, and Ali fell to the canvas with both gloves and his right knee on the canvas. As the referee stepped in, Ali rose from the canvas. The referee wiped Ali’s gloves, but did not signal a knockdown, as the two fighters resumed battle.

Near the end of round 11 Frazier again staggered Ali with a left hook as Ali stumbled and grabbed at Frazier to keep his balance. He then stumbled to the ropes, bounced forward into a clinch with Frazier until the two were separated by the referee. As the round closed, Ali clowned his way back to his corner, with Frazier appearing in control.

Sports Illustrated’s William Nack would later write of the fight some years later:

“…It was soon clear that this was not the Ali of old, the butterfly who had floated through his championship years, and that the long absence from the ring had stolen his legs and left him vulnerable. He had always been a technically unsound fighter: He threw punches going backward, fought with his arms too low and avoided sweeping punches by leaning back instead of ducking. He could get away with that when he had the speed and reflexes of his youth, but he no longer had them, and Frazier was punishing him.”

For the next three rounds, to the end of round 14, according to the judges’ scorecards, Frazier had the advantage on points for those rounds by all three judges. However, in the 14th Ali had pounded Frazier with some of his best punches of the fight.

In the final round, round 15, Ali’s legs appeared leaden, and Frazier wasted no time moving in on him. After a minute or so into the round, Frazier landed a powerful left hook – described in one account as “an absolutely titanic left hook” – that put Ali on his back. Some photos show Ali going down hard, with legs in the air and the red tassels on his shoes flying. It was only the third time in Ali’s career that he had been floored.

With Ali on the canvas, referee Arthur Mercante escorted Frazier to his corner. Ali got up quickly from Frazier’s blow, as Norman Mailer wrote his Life magazine piece:

…[Y]et Ali got up, Ali came sliding through the last two minutes and thirty five seconds of this heathen holocaust in some last exercise of the will, some iron fundament of the ego not to be knocked out… something held him up before the arm-weary triumphant near-crazy Frazier who had just hit him the hardest punch ever thrown in his life… and they went down to the last few seconds of a great fight, Ali still standing…

As he rose from the canvas, Ali’s jaw was now visibly swollen from earlier hits. He managed to stay on his feet as the fight resumed, but Frazier continued to land several more solid hits on Ali as the round ended. A few minutes later the judges made it official: Frazier had retained the title with a unanimous decision, dealing Ali his first professional loss.

As the post-mortems of the fight came in among fans and commentators, there seemed to be some consensus that Ali wasn’t prepared for the fight; that he was not in his best physical shape; and that he failed do the proper amount of training. Frazier, on the other hand was in top form.

Life photographer John Shearer, had spent weeks with both fighters before the bout, had taken lots of photos of Ali and Frazier during their respective training camps, and would later observe of Frazier:

“When I see the pictures I made of Joe running by himself, for example, the one thing that strikes me, maybe even more now than when I was making the photos, is his discipline. He was training, training, training. He was driven. And in many ways, he was a man alone.”

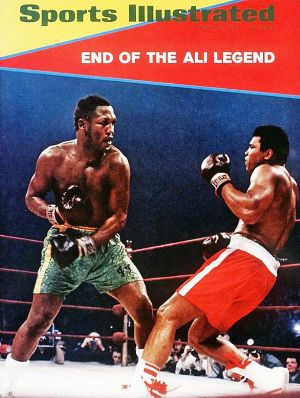

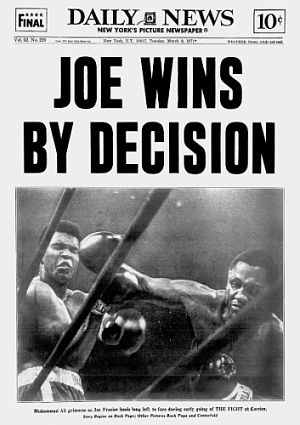

Following the fight that night, there was a party for Frazier. But both fighters would spend some time in the hospital getting checked out. Sports news headlines the next day across the country announced the Frazier victory. Sports Illustrated put Frazier’s 15th round knock down punch of Ali on the cover with the headline, “End of the Ali Legend.” But that assessment would prove way premature.

NY Daily News, March 1971: “Joe Wins By Decision.” |

And even before the fight had ended with Frazier the victor, there was talk of a rematch between the two. And indeed there would be a rematch – in fact, two more celebrated bouts between these two phenomenal boxers, a series of battles that would entwine their names forever as a pair in the annals of boxing history. More on those in a moment.

With his victory and prize money, Joe Frazier was able to leave his mark on his native state of South Carolina, where he spent his dirt-poor farm days as a boy. In 1971 he bought a 368-acre estate called Brewton Plantation near his boyhood home. He also became the first black man since Reconstruction to address the South Carolina Legislature.

Ali, too, had a good outcome in 1971. On June 27, 1971, by a vote of 8-0 (with Justice Thurgood Marshall abstaining) the U. S. Supreme Court overturned Ali’s conviction for draft evasion, clearing him of all charges.

Following the 1971 Ali-Frazier fight, Frazier defended his title in two 1972 bouts – one against Terry Daniels and the other with Ron Stander, beating both by knockout, Daniels in the fourth round and Stander in the fifth. In another defense of his title in January 1973 he lost the championship to George Foreman. But six months later, he rebounded with a July 1973 victory over Joe Bugner in London, on his way to becoming a contender again.

After his loss to Frazier in 1971, Ali went on a tear, winning six fights the following year – beating Jerry Quarry, Floyd Patterson (for the second time), Bob Foster, and three others. In 1973, Ali suffered the second loss of his career at the hands of Ken Norton, who broke Ali’s jaw during the fight.

After initially seeking retirement, Ali went back into the ring and won a controversial decision against Norton in their second bout. This led to a rematch with Joe Frazier who had lost the title to George Foreman. In January 1974, Ali scored a 12-round decision over Frazier in a non-title bout at Madison Square Garden. This put the pair even after their two bouts, each with one win.

Ali then took on heavyweight champion George Foreman on October 30th, 1974 in the famous “Rumble-in-the-Jungle” fight in Kinshasa, Zaire. Foreman was considered one of the hardest punchers in heavyweight history, and few believed Ali would prevail. But Ali cagily tired out Foreman, and in the eighth round hit Foreman with a combination that sent big George to the mat and down for the count.

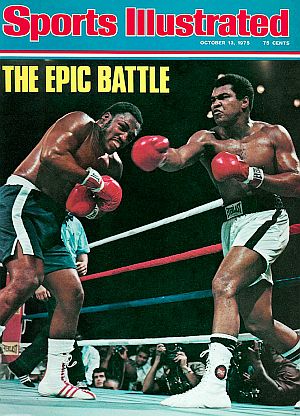

Ali, now champ, then dispensed with challengers in three subsequent fights, one of whom was Chuck Wepner, a New Jersey fighter who inspired Sylvester Stallone’s first Rocky film. Then came the third Al-Frazier fight on October 1st, 1975, better known known as the “Thrilla in Manila.”

The “Thrilla in Manila” championship bout is regarded as one of the greatest fights in boxing history. It ended after 14 grueling rounds when a battered Frazier, one eye swollen shut, did not come out to face Ali for the final 15th round. Ali too, was exhausted in his corner, collapsing on the canvas not long after the fight’s end, and later calling the battle a near-death experience.

But over the years, Ali never let up on Frazier with his taunts and name-calling. In the build-up to “The Thrilla in Manila,” Ali called Frazier “the other type of negro,” “ugly,” “dumb,” and “gorilla,” while waving around a hand-held toy gorilla he used with the media when taunting Frazier.

Some believed Ali’s name-calling of Frazier tarnished his standing among his own supporters. Author David Halberstam would later write that Ali was able to manipulate and deal with the media in ways that Frazier could not. But that in demeaning Frazier – “in letting the game become too cruel, Ali [was] diminished in the eyes of those of us who admired him and wanted him in every way to be worthy of his own greatness.”

“The truth was,” wrote Halberstam, “that Joe Frazier was never a Tom, and he was not a white man’s fighter, nor in any way was he political… Frazier’s only politics were his fists. Fighting was his only ticket out of the cruelest kind of poverty.”

After a few more fights, Joe Frazier retired in 1976. He staged an unsuccessful one-fight comeback attempt in 1981. He then retired again and began operating a training gym in Philadelphia.

Ali continued fighting through the 1970s, suffering punishing bouts with Ernie Shavers in Sept 1977 (though winning) and Larry Homes in Oct 1980, a fight stopped in the 11th round by Ali’s trainer, Angelo Dundee. The Holmes fight is said to have contributed to Ali’s Parkinson’s disease. Ali fought one last time on December 1981 against Trevor Berbick, losing a ten-round decision.

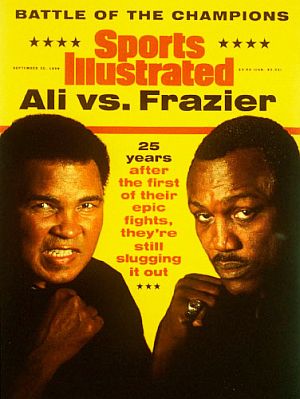

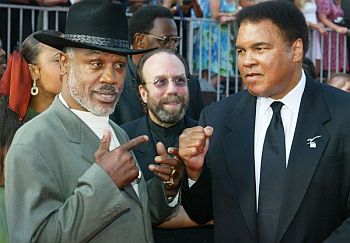

One testament to the famous standing of the 1971 Ali-Frazier bout came in a special Sports Illustrated issue at the fight’s 25th anniversary in 1996 which featured the two titans once again opposite each other on the cover, with the tag line: “25 Years After the First of Their Epic Fights, They’re Still Slugging it Out.” But this piece also recounted the long-standing personal bitterness between the two over Ali’s name-calling and demeaning of Frazier.

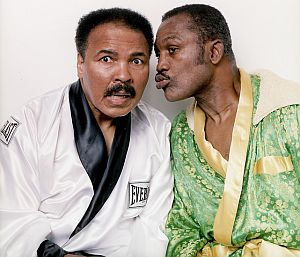

July10th, 2002: Frazier and Ali pose together as they arrive at the 10th annual ESPY Awards in Hollywood. Reuters/Fred Prouser

By that time, even some of Frazier’s closest aides felt he was carrying the bitterness too long and too deeply for his own good.

At the 30th anniversary of the first Ali-Frazier bout, in March 2001, Ali wrote in the New York Times: “Joe is right (to be bitter). I said a lot of things in the heat of the moment that I shouldn’t have said. Called him names I shouldn’t have called him. I apologize for that. I’m sorry. It was all meant to promote the fight.” Yet many believe the part about selling tickets and promoting the fights was bogus, since there was plenty of that going on elsewhere.

Privately, however, Frazier had said for years that he wanted a personal, face-to-face apology from Ali. Still, when Frazier, arriving late at the 30th anniversary gathering, was told of Ali’s statement which Ali had also made to the press there, Frazier was reported to have said: “We have to embrace each other. It’s time to talk and get together. Life’s too short.” Frazier was also reported to have told Sports Illustrated in May 2009 that he no longer held hard feelings towards Ali.

September 2015: A 12-foot bronze statue of Joe Frazier in his boxing stance was dedicated in front of the NBC Sports Arena at the Xfinitiy Live site in south Philadelphia.

In retirement, Joe Frazier often felt overshadowed by Ali’s various awards and notices, and he seemed to be left out of the historic recognition traditionally accorded professional boxers of his standing. Adding insult to injury was the fact that the fictional Rocky Balboa character from the Sylvester Stallone /Rocky film series had a statue in Philadelphia, while the city’s most renowned real boxer of recent years did not. This was not unnoticed by Jesse Jackson, who, while eulogizing Frazier at his funeral, made prominent mention of the slight. A few years later, however, in mid-September 2015, a 12-foot bronze statue of Joe Frazier in his boxing stance was dedicated in front of the NBC Universal Sports Arena at the Xfinitiy Live site in south Philadelphia. Statue artist Stephen Layne said he modeled his work on the famous knock-down punch Frazier leveled on Ali in the 15th round of their March 1971 fight. “I found my inspiration in that photo,” Layne said.

Ali, meanwhile, remains one of the greatest heavyweight boxers of all time, and also one of the most recognized sports celebrities in the world.

Ali’s professional boxing record over a 21-year career between 1960 and 1981 stands at 56-and-5, one of the best of all time — with 56 wins (37 knockouts and 19 decisions), and 5 losses (4 decisions and 1 knockout).

After retiring from boxing in 1981, he received all manner of sports and other awards and recognition, met with presidents and heads of state, served on various national and international committees, and lent is name to various causes.

In 1991 he traveled to Iraq during the Gulf War and met with Saddam Hussein in an attempt to negotiate the release of American hostages. In 1996, he bore the Olympic Torch to light the flame at the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta, Georgia.

Although Ali was diagnosed with Parkinson’s syndrome in 1984, he remained active for a number of years after his diagnosis. In 2005, Ali was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President George W. Bush during ceremonies at the White House.

After being hospitalized with a respiratory illness on June 2, 2016, Ali died the following day. He was 74. On June 10, 2016, his funeral procession went through the streets of his hometown, Louisville, KY, and a public memorial was held there, watched on television by an estimated 1 billion viewers worldwide, attended by many dignitaries and sports leaders. (Click on Ali/Frazier book covers above to view Amazon pages for those books).

For other stories at this website, see for example: the “Annals of Sport” category page; “Baseball Stories, 1900s-2000s,” a topics page with 14 baseball stories; “The Rocky Statue, 1980-2009,” story on the 20-year controversy over the location of a Rocky Balboa statue at the Philadelphia Art Museum; and “Dempsey vs Carpenteir,” a recounting of the famous 1921 fight between Jack Dempsey and George Carpenteir and the role radio played in making that fight one of the first “mega sports events.” Additional civil rights history can be found at “Civil Rights Topics,” a category page with 14 additional stories.

Thanks for visiting – and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research and writing at this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

________________________________________

Date Posted: 9 November 2015

Last Update: 22 September 2021

Comments to: jdoyle@pophistorydig.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Ali-Frazier History: Boxing & Culture,

1960s-70s,” PopHistoryDig.com, November 9, 2015.

________________________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

Official program from Ali-Frazier fight, March 8, 1971, with cover art by LeRoy Neiman, famous painter of athletes. |

July 24, 1971: Muhammad Ali – shown here on the eve of Jerry Ellis fight -- appeared on Sports Illustrated covers 39 times, more than anyone except Michael Jordan. |

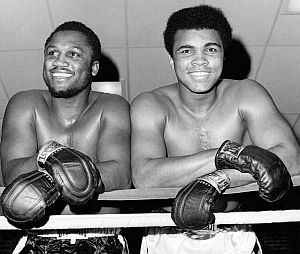

Joe Frazier and Muhammad Ali as young boxers. |

2003: Muhammad Ali & Joe Frazier pictured in their 1971 robes at Joe Frazier’s Philadelphia Gym; Frazier shown here in a forgiving pose. (Walter Iooss Jr./SI). |

“Fight of the Century,” Wikipedia.org.

David R Arnott,, “Frank Sinatra Photographs Joe Frazier for Life Magazine,” NBCNews .com, November 8, 2011.

“Sport: The Dream (Cassius Clay cover story),” Time, Friday, March 22, 1963.

“Cassius Clay in London” (cover), Sports Illus- trated, June 10, 1963.

Martin Kane, “The Art of Ali,” Sports Illus- trated, May 5, 1969.

“Sport: Bull v. Butterfly: A Clash of Cham- pions,” Time, Monday, March 8, 1971.

Ralph Graves, Managing Editor, Editor’s Note, “Some Staff Prediction on the Big Fight,” Life, March 5, 1971, p. 3.

Thomas Thompson, “The Battle of the Undefeated Giants: Joe Frazier and Muhammad Ali Square Off for $2.5 Million Each” (photos by John Shearer), Life, March 5, 1971, p. 40.

Hugh McIlvanney, “When the Mountain Came to Muhammad,” The Guardian, March 9, 1971 (and November 8, 2011).

Norman Mailer, “Ego” (feature story on the Joe Frazier-Muhammad Ali fight), Life, March 19, 1971, pp. 18-36.

“Muhammad Ali,” Wikipedia.org.

“Joe Frazier,” Wikipedia.org.

Thomas Hauser, Muhammad Ali: His Life and Times, Simon & Schuster, 1991, 544 pp.

Joe Frazier with Phil Berger, Smokin` Joe: The Autobiography of a Heavyweight Champion of the World, Macmillan USA, 1996, 213 pp..

William Nack, “Twenty-Five Years Later, Ali and Frazier Are Still Slugging it Out,” Sports Illustrated, September 30, 1996.

David Remnick, King of the World: Muhammad Ali and the Rise of an American Hero, Random House, October 1998, 326 pp.

David Halberstam, Page 2 Columnist, “Ali Wins Another Fight,” ESPN.com, 2001.

Michael Silver, “Where Were You on March 8, 1971?,” ESPN Classic, November 19, 2003.

Michael Arkush, The Fight of the Century:Ali-vs Frazier, March 8, 1971, John Wiley & Sons, September 2007, 272 pp.

Alan H. Levy, Floyd Patterson: A Boxer and a Gentleman, McFarland, 2008, 297 pp.

“Frazier Gets His Time to Shine” (HBO film), Sports Illustrated, April 22, 2009.

“Ali: The Louisville Lip”(photo gallery), Louisville Courier Journal, November 30, 2009

“Storytime With George Lois, Part 2,” Jux- tapoz.com, November 29, 2010.

Michael Arkush, “Fight of The Century Remains Unmatched 40 Years Later,” Boxing Experts Blog, March 7, 2011.

Richard Goldstein, “Joe Frazier, Ex-Heavyweight Champ, Dies at 67,” New York Times, November 7, 2011.

Associated Press, “Boxing Great Joe Frazier, 67, Dies After Bout With Cancer,” The Oregonian, November 7, 2011.

JekyllnHyde, “Lawdy, Lawdy, He’s Great” – A Profile in Political Courage,” DailyKos.com, November 19, 2011.

Geoff Stanton, “Ego and ‘The Fight of the Century’ | Muhammad Ali and Smokin’ Joe Frazier New York City 1971,” FromTheBar- relHouse.com, December 18, 2011.

Roosterman Productions, “Smokin Joe Frazier – The Final Goodbye” (w/Johnny Cash tune, “Hurt”), YouTube.com, posted, December 31, 2011.

“The Passion of Muhammad Ali,” Steven Lebron.com, July 16, 2012.

“Meeting Mr. Time: The National Portrait Gallery Celebrates the Genius of Boris Chaliapin, Time Magazine’s Most Prolific Cover Artist,” Montage Magazine, December 23, 2013.

Richard Hoffer, Bouts of Mania, Da Capo Press, July 2014, 296 pp.

Ben Cosgrove, “Ali, Frazier and The ‘Fight of the Century’: A Photographer Remembers,” Time.com, October 10, 2014.

“Sports Fan: Frank Sinatra,” Photo Gallery, Sports Illustrated.

“Muhammad Ali vs. Joe Frazier Crowd” (30 images), J. P. Laffont, New York, NY.

“Muhammad Ali Sportsman Legacy Award” (and cover gallery), Sports Illustrated, October 5, 2015.

Mark Kram, Ghosts of Manila: The Fateful Blood Feud Between Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier, Harper, 2001, 244 pp.

Bob Mee, Ali and Liston: The Boy Who Would Be King and the Ugly Bear, Skyhorse Publishing, 2011, 336 pp.

_______________________________