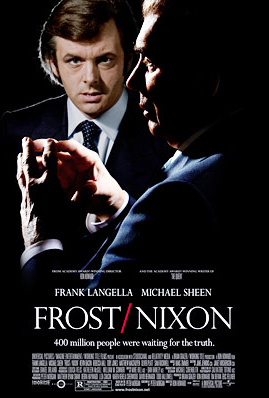

Poster for the 2006-2007 stage play ‘Frost/Nixon’ based on the 1977 television interviews of former President Richard Nixon by British talk show host, David Frost.

Nixon agreed to be filmed by Frost for a series of “tell-us-what-happened” TV interviews. It would be the first time the American public would see and hear Nixon in a series of no-holds-barred TV interviews since resigning from office. Nixon agreed to do more than 20 hours of on-camera interviews with Frost and would receive $1 million or more in fees and profits for the sessions.

Frost pulled something of a coup in getting the exclusive sessions with Nixon, upstaging American journalists and broadcast networks. The initial interviews were compressed and edited into a series of 90-minute TV shows that were then broadcast in May 1977 and watched by millions. But the interviews themselves were just the beginning.

In the wake of their initial broadcast, and over the next 30 years, a small cottage industry grew up around the event, spawning a series of books, VHS tapes, DVDs, stage productions, a Hollywood film, and a fair amount of ongoing debate. Part of that story follows here.

Background

Richard Nixon had resigned as President of the United States on August 9th, 1974. His political demise was brought about principally by the 1972 Watergate affair: an illegal caper involving clandestine operatives. The operatives — later linked to the White House and Nixon’s re-election committee — were caught bugging the Democratic Party’s national headquarters at the Watergate office building in Washington, D.C. Nixon and his team maneuvered to cover up their connection to this crime in what then became additional illegal activities including obstruction of justice. A protracted legal and political battle ensued over the next two years between Nixon’s White House and those pursuing the case, including: the national media and the press, the U.S. Congress, two Special Prosecutors, and the U.S. Supreme Court. All of this culminated in the July 1974 House Judiciary Committee’s vote approving two articles of impeachment. Headed for a certain trial in the U.S. Senate, Nixon pre-empted that possibility by resigning.

Nixon’s departing ‘victory’ salute as he leaves the White House by helicopter after his 1974 resignation as President.

Golden Boy vs. Nixon

David Paradine Frost had been something of TV phenom in Britain during the early 1960s. In his 20s, he was among a group of young entertainers that broke new ground on British television with an aggressive weekly show of satire called That Was the Week That Was. Begun in 1962, the show lampooned the British Establishment and became a popular success. Frost and the show caught America’s attention in 1963 when they paid serious homage to assassinated President John F. Kennedy. A U.S. version of the show, also featuring Frost, ran on NBC from January 1964 to May 1965. He soon had various TV business interests and other TV talk shows in Britain and the U.S. The David Frost Show ran in America for three years and won a primetime Emmy in 1970. During that time, Frost had become a trans-Atlantic jet setter, also known as something of a playboy, dating a range of models and movie stars, among them: Diahann Carroll, Karen Graham, Carol Lynley, Liv Ullmann, and Bibi Andersson. Wrote People magazine of Frost in 1975: “Once he flew 60 friends to Bermuda just for lunch, and it delighted him the time he beat out a Rothschild for a chartered jet to take a girlfriend to dinner in Vienna.”

David Frost, in 1968 photo with a young Candice Bergen, was known as something of jet-setter and playboy in the 1960s and 1970s. -Time, Inc. photo

Richard Nixon, meanwhile, in addition to being a disgraced former president, was in debt big time. He had huge legal bills and back taxes to pay. By 1975, Nixon was angling for book deals and possible TV interviews as ways to raise funds. But Nixon did not want any of the well-known U.S. journalists to interview him, such as Walter Cronkite, David Brinkley, or others from the CBS show, 60 Minutes. Nixon also planned to extract a handsome price for any interview, and that would help rule out some of the American networks that had policies prohibiting payment for interviews. In fact, about that time, a controversy had broken out over CBS paying H.R. Haldeman, a Nixon aide, for an on-camera interview, prompting charges of “check-book journalism.”

David Frost in 1968 at a London news stop – by then a TV personality with business interests in news & media. - Time, Inc., photo.

In July 1975, after Nixon signed his $2 million deal with Warner Books for his memoirs, his literary agent, Irving Lazar, also began talking with the TV networks in New York about a Nixon interview. NBC was interested and had placed a bid to interview Nixon, reportedly at $400,000. Frost then made Nixon a new offer: $500,000 for four shows. Frost made his offer through Nixon’s former communications chief, Herb Klein, then an executive at Metromedia in Los Angeles. But Nixon’s agent, Irving Lazar, wanted more money. Frost then raised his offer to $600,000 also giving Nixon a cut of the profits. NBC did not match Frost’s bid. Frost then had his deal. Lawyers for each side hashed out the details in a 13-page contract. Nixon would be available for at least 20 hour-long taping sessions that would later be edited for a series of TV shows. The interviews would not air before 1977 so as not to be a factor in the 1976 elections. Under the terms of the contract, Nixon would have no control over content of questions or editing, and would not see any of the questions in advance. “Nixon can, of course, refuse to answer questions,” Frost told reporters. “But then I am able to film his refusing to answer.”

When the deal was first announced, Nixon’s agent, Irving Lazar, said that Nixon had chosen Frost because of Frost’s “unique and wide-ranging experience.” But there was more to it than that. Nixon also wanted a certain kind of journalist, one who was not confrontational, and one who Nixon thought he could out-smart. David Frost, then 36, appeared to fit the bill. Hearing of the Frost deal, some critics immediately tagged Nixon as opting for “show business” rather than the “news business.” “Can David Frost succeed where John Sirica, Archibald Cox and Leon Jaworski failed?”

–Time, May 1977 And Frost, they implied, was no news heavyweight, known for throwing soft balls rather than being a tough interrogator. Yet Frost was no stranger to the political arena, and had interviewed British heads of state and other world leaders. He had also interviewed Nixon in 1968, and in1970 was invited to the Nixon White House to emcee a Christmas party. Frost’s relaxed style of interviewing, some believed, was effective in extracting information without being overbearing. On The David Frost Show, he once interviewed Ted Sorensen, former aide to President John Kennedy, who said on the air that Senator Ted Kennedy, a longtime friend, could not run for President in the aftermath of his 1969 Chappaquiddick incident. Still the conventional wisdom among newsmen and others at the time was that Frost was not tough enough for Nixon, and would not succeed in doing what a federal judge and two special prosecutors failed to do. “Can David Frost succeed where John Sirica, Archibald Cox and Leon Jaworski failed?,”asked Time magazine.

Images At Stake

The planned televised interviews — with a huge audience likely in the U.S. and abroad — had seeming benefits for both Nixon and Frost. For Nixon, the interviews would present a chance to salvage his presidential reputation, make his case to the American public, and review his diplomatic and other presidential accomplishments. For Frost, the interviews would be a chance to prove himself a serious interviewer and also elevate his celebrity credentials. But for both men there were risks as well. Television in the past had both hurt and helped Nixon — saving him in 1956 in his “Checkers Speech” which kept him on the Eisenhower ticket, and costing him dearly in 1960s with a poor showing in the first televised presidential debate with John F. Kennedy. Frost, too, faced the risk of failure with Nixon in front of millions, which could sink the remainder of his career. But both men were ambitious, even in their respective desperations. Frank Langella, who would later play Nixon in both the stage and film versions of Frost/Nixon, observed that the two men had much in common by 1977. They both had their share of critics, Langella noted, and both had reputations that were sullied or damaged. They were also “two men born of modest circumstances who had immortal yearnings,” Langella added. “They had a great desire to get to the top of the ladder — and stay there.”

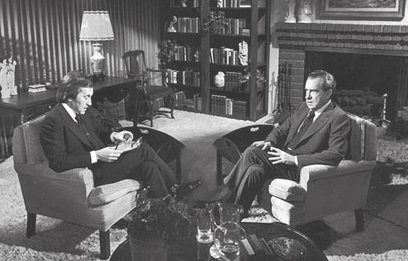

David Frost and Richard Nixon during one of the taping sessions in California, March-April 1977.

Richard Nixon and James Reston, Jr. in 1977. Reston would later write the 2007 book, ‘The Conviction of Richard Nixon,’ an inside account of the Frost-Nixon interviews (see later, below).

The taped interviews occurred between March 23rd and April 20th, 1977, and they covered every aspect of Nixon’s presidency. The taped sessions were then edited and compressed into initially four 90-minute TV shows, and later, a fifth show. The sessions with Nixon, however, proved frustrating to Frost and his team, as initially they failed to extract much of anything that was really new. As the contracted hours ticked by, sometimes with Nixon running on with long-winded answers, Frost’s team worried that the whole enterprise would fall flat for lack of getting what they had hoped from Nixon: some admission of guilt and remorse for what he had done. Finally, in two sessions near the end of the taping, Frost became more aggressive and cornered Nixon into a confession of guilt and an apology. These would be the sessions edited for use as the “Watergate” segment; the show that would air first in the series, on May 4th, 1977.

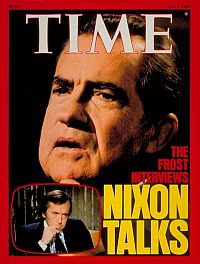

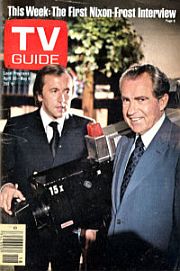

Broadcast & Advertising

At first, it was unclear whether the broadcast of the Frost-Nixon interviews would even get off the ground or have an adequate outlet, especially since the major U.S. networks then — ABC, CBS, and NBC — were not involved. Frost, however, found Syndicast, a New York-based independent TV marketing agency, to help sell broadcasting rights to individual stations, and eventually put together a network of 145 U.S. stations and 14 foreign outlets to air the broadcasts. Next was the matter of sponsors and advertisers. Initially, advertising sold poorly, but later picked up. In the immediate run-up to the first televised interview with Nixon, there was a heavy round of publicity. That week, major articles appeared on the interviews in Time, Newsweek and TV Guide. And on the Sunday evening preceding the first interview, CBS’s popular show 60 Minutes ran a 20-minute segment on the upcoming interview with Mike Wallace interviewing Frost about what he found. Time magazine, in fact, had arranged with Frost early on to have its Washington news editor, John Stacks, cover Frost’s taping of Nixon. Stacks, went to California for six weeks and essentially lived with the Frost staff in their Beverly Hills Hilton headquarters, looking at video tapes, interviewing Frost, and observing his staff strategy sessions. Time photographer John Bryson was also the only photographer allowed at the taping sessions and took a number of photos that appeared with Time‘s story. In covering the story, Stacks would observe that an “incredible number of Nixons” emerged from the former President during the interviews. “The shows are a kind of video psychobiography,” Stacks explained in the issue that hit newstands the week of the first interview.

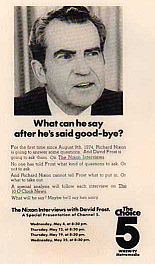

Local TV station ad for Frost-Nixon interviews, May 1977.

The first of the Nixon interviews — and the most forceful for Frost — which had actually come near the end of the taping sessions, aired on Wednesday evening, May 4th,1977 at 8:30 pm. It was during this session that Nixon made his admission about his part in the Watergate scandal: “I let down my friends,” he said. “I let down the country. I let down our system of government, and the dreams of all those young people that ought to get into government but now think it too corrupt… I let the American people down, and I have to carry that burden with me the rest of my life.” That episode drew 45 million viewers, about a third of the U.S. viewing public at the time. It was then the largest television audience in history for a public affairs telecast.

|

“I Have Impeached Myself”

FROST: …You got caught up in something and it snowballed? NIXON: It snowballed, and it was my fault. I’m not blaming anybody else. I’m simply saying to you that as far as I’m concerned, I not only regret it. I indicated my own beliefs in this matter when I resigned. People didn’t think it was enough to admit mistakes; fine. If they want me to get down and grovel on the floor; no, never. Because I don’t believe I should. On the other hand there are some friends who say, “just face ’em down. There’s a conspiracy to get you.” There may have been. I don’t know what the CIA had to do. Some of their shenanigans have yet to be told, according to a book I read recently. I don’t know what was going on in some Republican, some Democratic circles as far as the so-called impeachment lobby was concerned. However, I don’t go with the idea that there … that what brought me down was a coup, a conspiracy etc. I brought myself down. I gave them a sword, and they stuck it in and they twisted it with relish. And I guess if I had been in their position, I’d have done the same thing.  Nixon:1977 interview. FROST: Could you just say, with conviction, I mean not because I want you to say it, that you did do some covering up. We’re not talking legalistically now; I just want the facts. You did do some covering up. There was some time when you were overwhelmed by your loyalties or whatever else, you protected your friends, or maybe yourself. In fact you were, to put it at its most simple, part of a cover-up at times. NIXON: No, I again respectfully will not quibble with you about the use of the terms. However, before using the term I think it’s very important for me to make clear what I did not do and what I did do and then I will answer your question quite directly. I did not in the first place commit the crime of obstruction of justice, because I did not have the motive required for the commission of that crime. FROST: We disagree on that. NIXON: I did not commit, in my view, an impeachable offense. Now, the House has ruled overwhelmingly that I did. Of course, that was only an indictment, and it would have to be tried in the Senate. I might have won, I might have lost. But even if I had won in the Senate by a vote or two, I would have been crippled. And in any event, for six months the country couldn’t afford having the president in the dock in the United States Senate. And there can never be an impeachment in the future in this country without a president voluntarily impeaching himself. I have impeached myself. That speaks for itself. FROST: How do you mean “I have impeached myself”? NIXON: By resigning. That was a voluntary impeachment. Now, what does that mean in terms of whether I … you’re wanting me to say that I participated in an illegal cover-up. No. Now when you come to the period, and this is the critical period, when you come to the period of March 21 on, when Dean gave his legal opinion, that certain things, actions taken by, Haldeman, Erlichman, [attorney general John] Mitchell et cetera, and even by himself amounted to illegal coverups and so forth, then I was in a very different position. And during that period, I will admit, that I started acting as lawyer for their defense. “…And under the circum- stances I would have to say that a reasonable person could call that a cover-up. I didn’t think of it as a cover-up. I didn’t intend it to cover-up.” NIXON: Let me say, if I intended to cover-up, believe me, I’d have done it. You know how I could have done it so easy? I could have done it immediately after the election simply by giving clemency to everybody. And the whole thing would have gone away. I couldn’t do that because I said clemency was wrong. But now we come down to the key point and let me answer it in my own way about how I feel about the American people. I mean about whether I should have resigned earlier or what I should say to them now. Well, that forces me to rationalize now and give you a carefully prepared and cropped statement. I didn’t expect this question, frankly though, so I’m not going to give you that. But I can tell you this …  Nixon:1977 interview. NIXON: I can tell you this. I think I said it all in one of those moments that you’re not thinking sometimes you say the things that are really in your heart. When you’re thinking in advance and you say things that are, you know, tailored to the audience. I had a lot of difficult meetings in those last days and the most difficult one, the only one where I broke into tears, frankly except for that very brief session with Erlichman up at Camp David, that was the first time I cried since Eisenhower died. I met with all of my key supporters just the halfhour before going on television. For 25 minutes we all sat around the Oval Office, men that I had come to Congress with, Democrats and Republicans, about half and half. Wonderful men. And at the very end, after saying thank you for all your support during these tough years, thank you particularly for what you have done to help us end the draft, bring home the POWs, have a chance for building a generation of peace, which I could see the dream I had possibly being shattered, and thank you for your friendship, little acts of friendship over the years, you sort of remember with a birthday card and all the rest. Then suddenly you haven’t got much more to say and half the people around the table were crying. And I just can’t stand seeing somebody else cry. And that ended it for me. And I just, well, I must say I sort of cracked up. Started to cry, pushed my chair back. NIXON: And then I blurted it out. And I said, “I’m sorry. I just hope I haven’t let you down.” Well, when I said: “I just hope I haven’t let you down,” that said it all. I had: I let down my friends, I let down the country, I let down our system of government and the dreams of all those young people that ought to get into government but will think it is all too corrupt and the rest.“Yep, I let the American people down. And I have to carry that burden with me for the rest of my life. My political life is over.” |

Obstruction of Justice

Frost also probed Nixon about directing his aides to have the CIA ask the FBI to stop following certain leads in its investigation of Watergate. In this exchange, Nixon admitted that an earlier claim he’d made — that he was only trying to keep the FBI out of national security matters — was “untrue.” Actually, Nixon in this case was trying to stop the FBI from tracing Watergate money back to his political committee. Nixon later tells Frost in the interview, “It was a grievous mistake to have gotten the CIA involved in this thing.” Still, in this exchange, Nixon insists this was not a criminal act. But Frost replies that Nixon knew that criminals would be protected. Nixon objects and tries to qualify, but Frost persists: “An obstruction of justice is an obstruction of justice if it’s for a minute or five minutes…” On the televised portion of the interviews at this point, Nixon appears shaken. He then says his “absence of motive” precludes any criminal intent. But Frost jumps on that and surprises Nixon, suggesting the ex-president’s knowledge of the law is incomplete. “The law states,” says Frost, “that when intent and foreseeable consequences are sufficient, motive is completely irrelevant.” Nixon says nothing and appears uncomfortable.

After the May 4th interview, the next three televised interviews ran in the same evening time slot, and were spaced evenly over the next three weeks, on May 12th, May 19th, and May 25th. In the May 19th session, for example, Nixon asserted that a president could order actions such as burglaries and eavesdropping against American dissidents — actions which he termed “legal” when the president ordered them.

|

Presidential Power

FROST: …The wave of dissent, occasionally violent, which followed in the wake of the Cambodian incursion [re: Vietnam War], prompted President Nixon to demand better intelligence about the people who were opposing him. To this end, the Deputy White House Counsel, Tom Huston, arranged a series of meetings with representatives of the CIA, the FBI, and other police and intelligence agencies.  1977 interview. FROST: These meetings produced a plan, the Huston Plan, which advocated the systematic use of wiretappings, burglaries, or so-called black bag jobs, mail openings and infiltration against antiwar groups and others. Some of these activities, as Huston emphasized to Nixon, were clearly illegal. Nevertheless, the president approved the plan. Five days later, after opposition from J. Edgar Hoover, the plan was withdrawn, but the president’s approval was later to be listed in the Articles of Impeachment as an alleged abuse of presidential power. FROST: So what in a sense, you’re saying is that there are certain situations, and the Huston Plan or that part of it was one of them, where the president can decide that it’s in the best interests of the nation or something, and do something illegal. NIXON: Well, when the president does it that means that it is not illegal. FROST: By definition. NIXON: Exactly. Exactly. If the president, for example, approves something because of the national security, or in this case because of a threat to internal peace and order of significant magnitude, then the president’s decision in that instance is one that enables those who carry it out, to carry it out without violating a law. Otherwise they’re in an impossible position. FROST: So, that in other words, really you were saying in that answer, really, between the burglary and murder, again, there’s no subtle way to say that there was murder of a dissenter in this country because I don’t know any evidence to that effect at all. But, the point is: just the dividing line, is that in fact, the dividing line is the president’s judgment?  1977 interview. FROST: Pulling some of our discussions together, as it were; speaking of the Presidency and in an interrogatory filed with the Church Committee, you stated, quote, “It’s quite obvious that there are certain inherently government activities, which, if undertaken by the sovereign in protection of the interests of the nation’s security are lawful, but which if undertaken by private persons, are not.” What, at root, did you have in mind there? NIXON: Well, what I, at root I had in mind I think was perhaps much better stated by Lincoln during the War between the States. Lincoln said, and I think I can remember the quote almost exactly, he said, “Actions which otherwise would be unconstitutional, could become lawful if undertaken for the purpose of preserving the Constitution and the Nation.”“…[I]s there anything in the Constitution or the Bill of Rights that suggests the president is that far of a sovereign, that far above the law?” – David Frost NIXON: Now that’s the kind of action I’m referring to. Of course in Lincoln’s case it was the survival of the Union in wartime, it’s the defense of the nation and, who knows, perhaps the survival of the nation. FROST: But there was no comparison was there, between the situation you faced and the situation Lincoln faced, for instance? NIXON: This nation was torn apart in an ideological way by the war in Vietnam, as much as the Civil War tore apart the nation when Lincoln was president. Now it’s true that we didn’t have the North and the South… FROST: But when you said, as you said when we were talking about the Huston Plan, you know, “If the president orders it, that makes it legal”, as it were: Is the president in that sense — is there anything in the Constitution or the Bill of Rights that suggests the president is that far of a sovereign, that far above the law? NIXON: No, there isn’t. There’s nothing specific that the Constitution contemplates in that respect. I haven’t read every word, every jot and every tittle, but I do know this: That it has been, however, argued that as far as a president is concerned, that in war time, a president does have certain extraordinary powers which would make acts that would otherwise be unlawful, lawful if undertaken for the purpose of preserving the nation and the Constitution, which is essential for the rights we’re all talking about. |

Frost & Nixon Gain

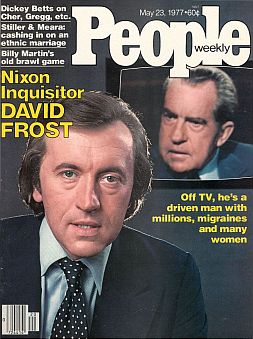

People magazine put Frost and Nixon on the cover of its May 23rd 1977 issue, around the time of the 4th televised interview.

For David Frost, the interviews were a major success, if only because Frost was the single journalist then to have such an extended and exclusive on-camera arrangement with the ex-president. The interviews gave Frost broad national and international exposure and elevated his celebrity. He was praised by some in the news media, and offered begrudging respect by others who had wanted the Nixon interviews. Some news executives conceded that Frost’s style was perhaps better than a more aggressive inquisitor such as 60 Minutes’ Mike Wallace. Barbara Walters reportedly cabled Frost after the Watergate session aired, saying: “I burst with pride for you last night. You were superb. Bravo!”

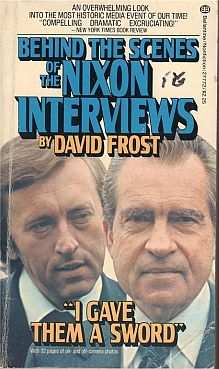

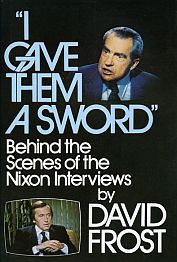

Cover of 1978 David Frost book telling 'behind the scenes' story of his interviews with fallen U.S. President, Richard M. Nixon. Click for book.

Frost also stood to make a fair amount of money from the interviews. In fact, even before the broadcasts were aired, the rights to foreign broadcasts alone had netted Frost $1 million. It was expected he would make more than $2 million in final profits. And given Nixon’s share of those profits, as specified in the contract, he too would make $1 million or more for the entire enterprise.

But there was still more to come for David Frost in the way of new opportunities, especially now that his reputation had been raised. But first, Frost would also get additional mileage from the interviews themselves. A fifth televised interview with Nixon was telecast in early September 1977 which focused on, among other things, the White House tapes that played a key role in Nixon’s downfall. Subsequent books and conflicting remembrances by Nixon aides H.R. Haldeman, John Erlichman and others kept the interviews and their aftermath in the news. And Frost himself added to this by writing a “behind-the-scenes” book on the interviews.

January 1978 Frost’s Book

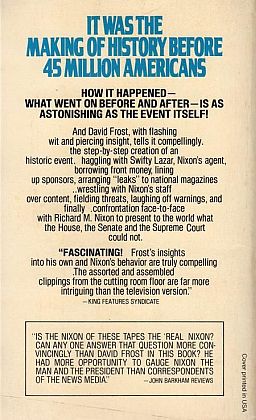

Frost’s book was published in January 1978 in London and New York. It used the title, “I Gave Them A Sword” (see cover above). The principal title line came from a phrase Nixon had used during the interviews. The book was published in hardback editions in London by Macmillan and in New York by Morrow. The book’s subtitle promised it would go behind the scenes of the Nixon interviews, which Frost did in the writing.

The 320-page book covered the story of the Nixon interviews from the beginning: how Frost first came up with the idea of interviewing Nixon; how he pursued and landed the deal; and how his financiers were became wary of the project. It also recounted the sessions with Nixon, the strategies involved on both sides, and what went on over the many days of taping. Part II of the book included the edited transcripts from the five TV telecasts, titled in the book as: “Watergate”, “The Huston Plan”, “Chile”, “Vietnam”, and “Kissenger”. The Frost book also revealed some newsworthy items, including the assertion that Alabama Gov. George G. Wallace was asked by Nixon to help him get the vote of an Alabama congressman to vote against impeachment. Wallace’s refusal to do this, helped clinch Richard Nixon’s decision to resign the presidency, according to Frost.

Paperback edition, back cover.

Frost by this time, had moved on to other ventures and would compile a long resume of media outings through the 1980s and early 1990s. Among his various U.S. and U.K. TV shows and specials were the following: Headliners With David Frost (1978), David Frost’s Global Village (1979-82), The Bee Gees Special (1979), The Kissinger Interviews (1979), The Shah Speaks (1980), The American Movie Awards (1980), Elvis — He Touched Their Lives (1980), The Royal Wedding (1981), Onward Christian Soldiers (1981), David Frost Presents the International Guinness Book of World Records (1981-86), Frost on Sunday (1981-92), Good Morning Britain (1982), Rubinstein at 95 (1982), Pierre Elliott Trudeau (1982), Frost Over Canada (1982-83), The Search for Josef Mengele (1985) The Guinness Book of Records Hall of Fame (1986-88), The Next President with David Frost (1987-88), Entertainment Tonight (1987-88), Through the Keyhole (1987-93), and in 1989, The President and Mrs. Bush Talking with David Frost.

Shown above is Vol.1 of the 1992 Universal Studios five-volume set. Click photo for box set of all 5 VHS tapes.

November 1992

Home Video Series

In November 1992, at the 20th anniversary of the Watergate scandal, MCA/Universal studios released “The Nixon Interviews With David Frost” in VHS home video format. The VHS format had been around since the late 1970s, but had become especially popular by the early 1990s.

MCA/Universal issued a five-volume series of cassettes, each then selling for $19.98. In the series, which is still available today, each volume covers the interviews as they were broadcast in 1977, organized generally around specific themes. Volume 1, titled “Watergate,” covers the Watergate scandal primarily, the payment of “hush money” to certain principals in the scandal, and related issues including impeachment. Volume 2, “The World,” covers Nixon’s international diplomacy and foreign policy, his dealings with China and Russia, his meetings with Mao and Brezhnev, and his relationship with Henry Kissinger. Volume 3, “War at Home and Abroad,” focuses on the Vietnam War, protests at home, and the effect of the War on Nixon’s presidential career. It also covers wartime strategy, wiretaps, “dirty tricks” and organized harassment to quell domestic protest. Volume 4, “The Final Days,” covers the last moments of a failed presidency, the pardon from president Ford, and the work of Washington Post reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein. Volume 5 is titled “The Missing 18 1/2 Minutes and More,” and covers the issue of a key missing segment from the White House tape recording system during the Watergate scandal and also the stories of Attorney General John Mitchell and his wife Martha.

|

“Blow The Safe And Get It!” David Frost’s 1977 interviews, of course, did not pry open all of Nixon’s nefarious deeds or the full force of his audacity. As more of the official record would come to light in subsequent years, the full picture of what Nixon was about would become even clearer. A tape that was released in 1996, for example, covered a meeting where Nixon and top aides Bob Haldeman and John Ehrlichman, along with Henry Kissinger, are discussing some documents that are held at the Brookings Institution in Washington — documents that could be embarrassing to the Democrats. Nixon reminds this group that something along the lines the Tom Huston’s plan of black-bag break-ins and dirty tricks might be in order. “You remember Huston’s plan?,” says Nixon. “Implement it,” he says. Kissinger adds at one point in this conversation, “Now Brookings has no right to have classified documents.” Then says Nixon: “Goddamn it, get in and get those files. Blow the safe and get it.” This is 1971, one year before the Watergate break-in of 1972, when the “black-bag” crew were about bugging Democratic Party campaign headquarters. |

1992 & Beyond

Watergate’s “Legs”

At the 20th anniversary of the Watergate scandal in 1992, there was a news and media revival around the scandal and all things Nixon. Seminars, talk shows, and new books came forth on Nixon and Watergate.

This activity has more or less repeated itself in subsequent years as Watergate principals have died off, confidential sources have come to light, or new information has surfaced from national and personal archives. Among some of these events, for example, have been: the death of Richard Nixon in 1994; newly released tapes in 1996; the 30th anniversary of Watergate break-in in 2002; the 30th anniversary of Nixon’s resignation in 2004; the revelation that FBI agent Mark Felt was the famed “Deep Throat” source for Washington Post reporter Bob Woodward in 2005. Similar spurts of activity would also come with new releases of Watergate-related White House tapes and/or new memoirs.

All of this activity helped to keep the “Nixon/Watergate” legacy in the news — and the market for “Nixon/Watergate” history, debate, and memorabilia very much alive — including the Frost-Nixon material. Watergate and Richard Nixon history would prove to have a long and continuing shelf life — or “legs,” as marketing and newspeople sometimes say of such phenomena. But by the mid-2000s, the Watergate legacy was heading in the direction of historical entertainment, and first, a stage production.

August 2006

The Play

Advertisement for the stage play, ‘Frost/Nixon,’ in London, 2006.

Poster for the ‘Nixon/Frost’ play, opened in London August 2006 and a year later in New York.

– Peter Morgan, playwright.

Morgan, too, had his own observations about Nixon, which he shared with The Guardian’s Gareth McLean in August 2006:

“Self-destruction is such an interesting thing for a dramatist, and what’s particular to Nixon is how human the failings were that led to his downfall. I really think he was a man who could have had greatness in his grasp. Despite being in a totally unassailable position — he’d reached détente with the Chinese, he presided over economic stability at home, he was about to be re-elected by a massive landslide — he snatched defeat from the jaws of victory. And if you look back over his career, he was a serial self-destructor. What he did with Watergate and the abuses of power were the actions of a man who, despite all evidence to the contrary, thought everyone was out to get him. He was so fabulously labyrinthine and tortured.”

On Broadway...

The play was Morgan’s first stage production, and it received high praise in the British press. “[A]s a study of two men in a camera combat, the play rivets the attention,” wrote Michael Billington of The Guardian on seeing the play at the Donmar in August 2006. “…I felt I had not only got a glimpse into the characters, but became nostalgic for an era when televison itself had a theatrical weight and power.” Benedict Nightingale of The Times, U.K., who also saw the play at the Donmar that August, observed of both the Nixon and Frost characters: “[N]ow we see the insecurity, the inner vulnerability the two men share and hope not to show. Factual, fictional, it makes for riveting drama.” After its run at the Donmar, the play continued to run in London’s West End.

The play in 2008 with Stacy Keach.

2007

Frost/Nixon Books

Cover of 2007 hardback book on the Frost/Nixon interviews by former Frost team member James Reston, Jr. Click for book.

Frost had personally recruited Reston in May 1976 to leave an academic post and join his Nixon interview research team. Reston became a key member of Frost’s team, writing for example, a 96-page interrogation strategy memo for Frost in the process. He also wrote a private narrative and journal of his experiences during the Frost/Nixon interviews, highlighting the tensions in the Frost camp and his own feelings and critique about what was then occurring. Reston put much of this material away and forgot about for 30 years. Then Peter Morgan called, and Reston once again became involved in the Frost/Nixon time warp, offering his views and knowledge about what had happened in 1977 as Morgan crafted his play. Reston dug out his old writing and shared it with Morgan and also spent time with Morgan and his cast in London as they developed the play. Reston soon published his manuscripts in book form as The Conviction of Richard Nixon in June 2007. Reston’s account of those interviews has become an important addition to the historical record and a necessary complement to the play and the subsequent Hollywood film. Reston himself, however, became somewhat unhappy with how certain events were compressed and omitted in both the play and film, though conceding that the realms of drama and history are quite different in terms of what each presents. Still Reston made his views public in a January 2009 Smithsonian magazine article.

Reston had made a key discovery when working for Frost back in 1977. He had found then-undisclosed transcripts of taped conversations between Nixon and Charles Colson — one of the Watergate conspirators. These conversations of February 13th and 14th, 1973, revealed Nixon’s role in the coverup. And Frost used this information at a key moment in the interviews. In 1977, James Reston had found undisclosed tran- scripts of taped conversa- tions between Nixon and Charles Colson. On the February 14th tape, Nixon says: “The cover-up is, is the main ingredient… That’s where we gotta cut our losses. My losses are to be cut. The President’s losses got to be cut on the cover-up deal.” In the interview, Frost’s citing of this taped exchange between Nixon and Colson stuns Nixon. Neither Nixon nor any member of his team had seen this transcript. The Colson tapes contradicted Nixon’s assertion that he first learned of the cover-up on March 21, more than a month later. At this point in the interviews, Frost had Nixon on the ropes, as it were, and he now burrowed in, charging Nixon that he knew a cover-up was underway more than a month before he formerly said he knew of it — in other words, that Nixon had lied. And in that moment, Nixon appeared flustered and beaten. On the Colson tapes, Nixon also ordered his aides to “turn over any cash we got” to buy the Watergate burglars’ silence, this being the “hush money.” All pretty devastating material.

2007 updated edition of David Frost’s 1978 book, ‘I Gave Them a Sword,’ that includes additional Frost narrative on the making of the stage play. Click for book.

Reston’s book then, with its actual record of the interviews, is an important supplement to play and film, especially for those who want the real sequence and substance of the 1977 interviews.

In addition to Reston’s book, an updated version of David Frost’s 1978 book, I Gave Them A Sword, was also released in October 2007. This time, the book was given the title, Frost/Nixon, in a bid to tie in with the play and the anticipated Hollywood film.

In this updated version, Frost explains the deal he made with Peter Morgan for the rights to produce the material as a play, and how he felt about it’s final casting plot and the character portrayals.

“Frost/Nixon provides the authoritative account of the only public trial that Nixon would ever have,” says the publisher on the book’s back cover. This is the story, continues the blurb, of “David Frost’s quest to produce one of the most dramatic pieces of television ever broadcast…”

December 2008

The Film

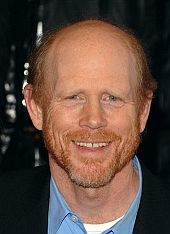

Ron Howard at premiere of 'Frost/Nixon' in New York, November 2008. (AP Photo/Peter Kramer)

…I was expecting to learn something. I was expecting to admire it. I wasn’t expecting to be on the edge of my seat…. I wasn’t expecting to laugh at it and with it the way I did. It’s such a rare thing to have, you know, something that as smart, unusual as this story, the way Peter Morgan framed it, and really have it be that engrossing an experience to watch it. …Even as I was watching it, I was beginning to get ideas about how the adaptation might work. …I fantasized grabbing a camera and jumping on stage and starting to move with these guys… I just began to feel a sort of a cinematic version of this in my mind. I became very ambitious for it, really wanted to do it…

Howard had been a famous child TV star playing the young boy, Opie Taylor, on the Andy Griffith Show of the 1960s, and as a teenager on Happy Days in the 1970s. After his acting years, Howard became a successful film director, producing a range of films, including: Splash (1984), Cocoon (1985), Far and Away (1992) Apollo 13 (1995), Cinderella Man (2005), A Beautiful Mind (2001), and The Da Vinci Code (2006). A Beautiful Mind received four Academy Awards, including those for Best Director and Best Picture.

After Howard saw Frost/Nixon in London, he became fascinated with the inside drama and the characters, and decided he wanted to make a film adaptation of the play. He had some previous dealings with British playwright Peter Morgan, who agreed to sell him the film rights and also work on the screenplay for the film. It was briefly rumored that Warren Beatty might play the role of Nixon, but Howard, struck by their performances he saw in the play, wanted to use both Frank Langella and Michael Sheen as the main characters in the film as well. “It became clear to me that anybody else was going to be walking in their shadows,” he would later say of Langella and Sheen in their respective roles, “and I really wanted film audiences to see what these actors could bring.”Still, Frost/Nixon on the big screen might be received somewhat differently than the stage play, described by one reviewer as “a good pick for the Atlantic Monthly/Harper’s crowd,” suggesting a limited, more intellectual audience. Morgan would acknowledge this in a conversation with one reporter in 2007, noting the difficulty of enticing people into test screenings: “If you go into a mall and say, ‘Would you like to come and see a film about the interviews done by David Frost and Richard Nixon in 1977?’, they just walk past you. They think you’re mad.”

But Howard was committed to bringing the edge-of-seat drama that he saw on stage to the film. He also wanted to show the human side of both Frost and Nixon, while being honest to the history as far as he could. “One of my goals was to never apologize for Richard Nixon or David Frost,” said Howard about making the film in an interview with Time magazine. “But certainly with Nixon, who has been so vilified, deservedly so in many ways, I also wanted you to understand what made him tick.” In fact, Howard had voted for Richard Nixon in 1972. He was 18 that year, as he explained to the New York Times’ Deborah Solomon in November 2008: “Richard Dreyfuss, when we were doing [the film] American Graffiti, was pumping me to vote for McGovern. But I think I wound up going for Nixon. I thought he could get us out of the Vietnam War quickly. Ha.” In depicting Frost, too, Howard wanted to capture Frost’s “entrepreneurship,” as he explained in his interview with Deborah Solomon:

…One of the things I probably emphasized was the pressure on David Frost and the entrepreneurship of the whole enterprise. Yes, Frost faces the difficult task of stopping Nixon from hiding behind long-winded and self-serving statements and getting him to apologize for Watergate. As an interviewer, that’s one thing. Frost’s pride and his reputation are at stake. But as a producer, it’s another thing. It was really new broadcast territory.

…The fact that David Frost had packaged this thing, had gained the rights, wanted to produce it and be the interviewer — the networks didn’t want to farm out something like that. What he did was create the first fourth network; the interviews ran on local stations all over the country.

Kevin Bacon as Nixon advisor Jack Brennan and Frank Langella as Nixon in a scene from Ron Howard’s film, ‘Frost-Nixon’.

Still others were emphatic about historic distortion in the film or how Nixon was presented, including former Washington Post Watergate-era editor Ben Bradlee. “They never should have let him apologize in the film,” he said of Nixon’s portrayal after seeing the film at a VIP screening in December 2008. “Nixon never was sorry for what he did.” Elizabeth Drew, a journalist who wrote on politics at the time of Watergate and Nixon’s downfall, was also unhappy with the film, and said so in a detailed Huffington Post.com article:

…[I]t’s because of the enormously historical importance of that period that the film raises serious questions of its legitimacy. The film’s plot is a contrivance; its telling is so riddled with departures from what actually happened as to be fundamentally dishonest; and its climactic moment is purely and simply a lie. Literary license in the name of drama or entertainment is one thing; the issue comes down to what one is taking license with, and the degree of license being taken.

For others, however, the film succeeded in doing what Howard hoped it would do — i.e., to bring viewers into the inside drama of the contest and the strategizing between Frost and Nixon. “Neither the title nor the subject matter prepares you for the pure fun of ‘Frost/Nixon,'” wrote Washington Post’s movie critic Philip Kennicott in a December 2008 review. “…You expect something dry, historical and probably contrived. But you get a delicious contest of wits, brilliant acting and a surprisingly gripping narrative…” Adds Kennicott later in the same review:

…The writing is so good, the acting so powerful, that the film goes well beyond the courtroom drama into the territory of the classic history play. Nixon is Henry II, the fallen leader, and his call to Frost comes from a larger emotional dungeon than mere political disgrace. Frost, the young prince, the high-living Hal who needs to sober up if he’s to become Henry V, begins to take his quest seriously.

It isn’t Shakespeare, but it is drama at a level one doesn’t often get in the movies…

At the release of the Frost/Nixon film, David Frost reissued his book on the interviews, this time in paperback format in the U.K. using the title: Frost/Nixon: One Journalist, One President, One Confession. This version of the book was published by Pan Books as a media tie-in edition and went on sale in late November 2008. A new DVD of the Nixon interviews was also issued by Liberation Entertainment in early December 2008, using the title Frost/Nixon: The Original Watergate Interviews (1977). This DVD is 88 minutes long, and also includes new footage shot by Frost in 2007 in which he discusses his reactions to his 1977 encounter with Nixon and the historical impact of the interviews. Frost also shares his views on Peter Morgan’s interpretation and screenplay based on the interviews. A second DVD of the Frost/Nixon interviews is scheduled for release sometime in 2009. No doubt, the “Frost/Nixon” franchise will roll on for some years to come, intertwined as it is with Watergate, as well as the unending queries into the lessons of political power.

Frost & Nixon

After his 1977 interviews with Nixon, David Frost went on to do more interviewing and TV shows, among other things. As of 2008 he had interviewed the last seven American presidents and the last six British prime ministers. He was knighted in December 1992, becoming “Sir David Frost.” In later years, Nixon gained great respect in foreign affairs, consulted by Democrat and Repub- lican alike. When Frost visited The Daily Show in November 2008, host Jon Stewart suggested that Frost interview President George Bush about some of his administration’s controversial activities. Today David Frost is the host of the Al Jazeera English program, Frost Over the World.

Richard Nixon, on the other hand, lost his political career and was disbarred from legal practice in New York, and he resigned from legal practice elsewhere. But Nixon didn’t fade completely from the limelight. In fact, he went on to author ten books in his later life and maintained a routine of speaking, writing, and travel. In subsequent years, Nixon would be interviewed by journalists, book reviewers, and policy analysts. On occasion, he met with foreign leaders such as Japanese Prime Minister Yasuhiro Nakasone in Japan, Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping in China, and Mikhail Gorbachev in the Soviet Union. Despite his historic failings, Nixon gained great respect in foreign affairs, consulted by Democrat and Republican alike in later years. Libraries and institutes were opened in his name, including the Richard Nixon Library in Yorba Linda, California and the Nixon Center for Peace and Freedom, a Washington, D.C. Nixon suffered a stroke on April 18, 1994 and died four days later, at the age of 81.

History & Drama

The Nixon and Watergate legacies continue to be debated to this day, along with the Frost/Nixon interviews and their various interpretations — whether stage play, Hollywood film, or multiple books. These materials all provide, in their own way, a useful and provocative collection of history lessons from that time, and a window into politics and personality. Frost/Nixon — the play and the film — were clearly focused on portraying the drama of the contest as well as the human foibles of the two main characters, both flawed and looking for their respective rewards and/or redemptions. True, some licence was taken with the actual history, with some scenes wholly created or omitted, while others were fictionalized for the sake of good story telling. Still, these productions succeeded in capturing the essence of the Frost-Nixon contest, the larger principles then at stake for law and nation, and the quirkiness and human qualities of both Frost and Nixon. They also introduced and/or drew out some new facets — whether of the personalities themselves, the role of television, or the chess-game strategies involved in the interviews. In so doing, they serve history not as the most definitive accounts of what happened — as the books are certainly better for that, at least in a factual and chronological sense. Yet the play and film are important for their different, unique, and focused perspectives. They also serve as valuable reminders of what a major event this was in its day, as well as educational prods to learn more about a tragic man at the pinnacle of power and how a democratic state dealt with him.Other Richard Nixon-related stories at this website include: “Nixon’s Checkers Speech, September 1952” (during which the Vice President extricates himself from scandal through the “magic”of television); the “1968 Presidential Race” (featuring the Republican primaries and general election that year, Nixon’s election, and celebrities and other notables who helped Republican candidates, including Nixon); and, “Enemy of the President”(about cartoonist Paul Conrad and includes some of his famous Nixon and Watergate cartoons). Nixon is also covered in part in, “JFK’s 1960 Campaign.” Additional stories on politics can be found at the “Politics & Culture” category page. Thanks for visiting – and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research and writing at this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

__________________________________

Date Posted: January 15, 2009

Last Update: March 11, 2019

Comments to: jackdoyle47@gmail.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “The Frost-Nixon Biz, 1977-2009,”

PopHistoryDig.com, January 15, 2009.

______________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

Eric Pace, “Nixon Is Said to Be Open To $2-Million for Memoirs,” New York Times, Thursday, August 29, 1974, p. 23.

“Nixon Sells Hard-Cover Rights to Memoirs,” New York Times, Saturday, September 28, 1974, p.19.

“Memoirs of Nixon Rejected by CBS,” New York Times, July 20, 1975.

Les Brown, “NBC News Seeks Nixon Interview; Watergate Would Be Part; Fee Put at Under $1-Million,” New York Times, July 29, 1975.

“NBC Terminates Talks For Memoirs of Nixon,” New York Times, August 8, 1975.

“David Frost Signs To Interview Nixon; Sum Is Undisclosed,” New York Times, August 11, 1975.

Charles B. Seib, “The Richard Nixon Show,” Washington Post, August 18, 1975, p. A-20.

“Frost’s Big Deal,” Time, Monday, August 25, 1975.

“The New Nixon Tapes Are Just Another Deal for Media Showman David Frost,” People, September 01, 1975, Vol. 4, No. 9.

“Times Co. Buys Serial Rights to Nixon Memoirs; Work Will Be Offered Prior to Warner’s Publication of Book in Fall of ’77,” New York Times, Wednesday, June 16, 1976, p. 61.

Jack Anderson and Les Whitten, “Frost: Tough Questions for Nixon,” Washington Post, November 22, 1976, p. E-19.

“Nixon and Frost in May,” Washington Post, February 12, 1977, p. E-4.

Les Brown, “Advertising Spots for Nixon TV Interview Sell Slowly,” New York Times, February 14, 1977.

“Frost Reaffirms Control over Nixon Interviews,” New York Times, April 8, 1977.

Les Brown, “Last-Minute Publicity Drive for Nixon TV Series Helps Swell Ad Revenues and Network of Stations; …Hinted $2 Million in Gross Revenues…,” New York Times, Sunday, May 1, 1977, p. 27.

“Nixon Says Watergate Cover-Up Sought to Protect the Innocent,” Washington Post, May 2, 1977, p. A-3.

“Nixon-Frost Interviews,” ABC Evening News, Reporters: Harry Reasoner, Bob Clark, Barbara Walters, and John Scali, Wednesday, May 4, 1977.

Bob Woodward and Scott Armstrong, “Nixon Sheds Little New Light on Scandal,” Washington Post, May 5, 1977, p. 1.

Haynes Johnson, “Nixon Stirs All the Old Memories,” Washington Post, May 5, 1977, p. 1.

“Frost and a Researcher Disagree on Nixon Respite,” Washington Post, May 6, 1977, p. A-12.

James M. Naughton, “Nixon, Conceding He Lied, Says ‘I Let the American People Down,’ Denies Any Crime on Watergate,” New York Times, May 5, 1977 p. 1.

Les Brown, “Nixon’s TV Audience Placed at 45 Million; Surveys Rank Program With Leading Series,” New York Times, May 6, 1977, p. 1.

“Nixon Tells Frost Kissinger Differed on Cambodia,” New York Times, May 9, 1977.

“Nixon Talks,” Time, Monday, May 9, 1977.

“David Can Be a Goliath,” Time, Monday, May 9, 1977.

James M. Naughton, “Nixon Says a President Can Order Illegal Actions Against Dissidents; In Frost Interview on TV Tonight,” New York Times, May 19, 1977, p. 1.

Fred Hauptfuhrer, “Frost’s Frontiers,” People, May 23, 1977, Vol. 7, No. 20.

“Nixon Admits Plan To Use Hughes Cash,” Washington Post, May 25, 1977, p. A-2.

Jonathan Steele, Washington correspondent, “Frost’s Standing Rises in The U.S.,” The Guardian, Friday May 27, 1977.

George Gallup, “Intense Dislike Of Nixon Eases After TV Show,” Washington Post, May 29, 1977, p. 55.

Clay F. Richards, “Watergate Legacy After 5 Years: Fame, Disgrace,” Washington Post, June 17, 1977, p. A-1.

Les Brown, “Frost Plans 5th In Nixon Series,”New York Times, August 2, 1977.

James M. Naughton, “Watergate Evidence Cited in Frost Talk; Nixon Says He Told Aide to Ruin Tapes,” New York Times, Sunday, September 4, 1977, p. 1.

“Excerpts From Interview With Nixon About Watergate Tapes and Other Issues,” New York Times, Sunday, September 4, 1977, p. 24.

Lou Cannon, “Haldeman Disputes Nixon on Tapes,” Washington Post, September 12, 1977, p. A-10.

Associated Press, “Frost Quotes Nixon: Wallace’s Reticence Cinched Resigning,” Washington Post, January 27, 1978, p. A-9.

“‘The Ends of Power’: It’s Haldeman’s Turn To Talk,” Washington Post, February 3, 1978, p. D-2.

Haynes Johnson, “Nixon, Haldeman, Frost and… Hype,” Washington Post, February 15, 1978, p. A-3.

“Haldeman Accuses Nixon,” Washington Post, February 16, 1978, p. A-1.

David Frost, I Gave Them A Sword: Behind the Scenes of the Nixon Interviews. New York: Morrow, 1978.

Tom Zito, “The News That Makes the Books: There’s Big Money in the Jump From Front Page to Best-Seller List; The Big Book Push,” Washington Post, May 6, 1978, p. B-1.

Fred Emery, Watergate: The Corruption and Fall of Richard Nixon, 1994.

Bob Minzesheimer, “Frost Rewinds Nixon Tape to 1977 and Hits Play,” USA Today, October 22, 2006.

Rita Zajacz, “David Frost: British Broadcast Journalist/Producer,” The Museum of Broadcast Communication, viewed, January 2008.

“Frost/Nixon Interviews,” Wikipedia.org

Peter M. Nichols, “Home Video; Promoting the Famous,” New York Times, November 12, 1992.

Raymond Snoddy, “Frosty The Showman,” The Independent (London, U.K), Monday, May 30, 2005.

Fred Emery, “Making a Drama Out of a Crisis: Nixon’s Last Stand,” The Independent, Sunday, July 23, 2006.

Gareth McLean, “When The Playboy Met The Liar,”The Guardian, Tuesday, August 1, 2006.

Vincent Dowd, “Historic Nixon Interviews On Stage,” BBC News, August 21, 2006.

Michael Billington, “Frost/Nixon”, The Guardian,(London), August 22, 2006.

Benedict Nightingale, “Frost/Nixon”, The Times (London), 22 August 2006.

“Trial by Television,” Book Review, The Conviction of Richard Nixon: The Untold Story of the Frost/Nixon Interviews, by James Reston, Jr., Book World, Washington Post, Sunday, July 15, 2007, p. 4.

Sylviane Gold, “The Interview That Was a Play Becomes a Film,”New York Times, November 2, 2008.

Deborah Solomon, “Talking Head: Questions for Ron Howard,” New York Times Magazine Sunday, November 9, 2008.

Stephanie Green, “Bradlee Slams ‘Frost/Nixon’: ‘Nixon Never Was Sorry’,” Washington Times, Tuesday, December 2, 2008.

“10 Questions for Ron Howard,” Time, Thursday, December 4, 2008, p. 2.

Manohla Dargis, “Mr. Frost, Meet Mr. Nixon,” New York Times, December 5, 2008.

Philip Kennicott, “Meant for Each Other: ‘Frost/Nixon’ Is a Good Fight With Two Winners,”Washington Post, Friday, December 12, 2008, p. C-1.

Elizabeth Drew, “Frost/Nixon: A Dishonorable Distortion of History,” Huffington Post.com, December 14, 2008.

Peter Morgan, “Morgan Savors Howard’s On-Set Vibe; Duo’s ‘Frost/Nixon’ Confab Produces a Winner,” Variety.com, December 18, 2008.

James Reston, Jr., “Frost, Nixon and Me,” Smithsonian, January 2009, pp. 86-92.

__________________________________________________