Richard Nixon, center, is flanked by Dan Rowan, left, and Dick Martin right, of ‘Rowan and Martin's Laugh-In’ TV show at October 1968 campaign stop in Burbank, CA. Nixon appeared on ‘Laugh-In’ in mid-Sept 1968 in the humorous 'sock-it-to-me' segment, covered later below. (AP photo)

Historically, Republicans were more suspicious of liberal-leaning Hollywood than Democrats. And Hollywood itself, especially after the communist witch hunts of the late 1940s and 1950s, was leery of politics generally.

“People in Hollywood are generally afraid to be active in politics,” said actor Dick Powell in September 1960. “This is especially true of some in television who believe that their sponsors would not want them to be identified with a political party.”

Another actor, Vincent Price, added in the same 1960 interview: “Here in Hollywood, actors are not supposed to have political opinions.” But many did, of course.

Dick Powell, for example, was then, in September 1960, heading up a group of Hollywood Republicans supporting the Richard Nixon-Henry Cabot Lodge ticket then bidding for the White House. But by the later 1960s, and in 1968 in particular, celebrity involvement in politics would become much more prominent.

Ronald & Nancy Reagan at victory party after winning the 1966 California governor's race.

Murphy & Reagan

In fact, by the mid-1960s, Republican actors began running for, and winning, public office. Actor/dancer George Murphy was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1964, and actor Ronald Reagan won the California Governor’s race in 1966. Murphy was a film actor who danced with Shirley Temple in the 1938 film Little Miss Broadway and acted opposite Judy Garland in Little Nellie Kelly (1940). Murphy became active in California politics in the 1950s and had served as director of entertainment for Dwight Eisenhower’s presidential inaugurations of 1953 and 1957. By 1964, Murphy became a politician himself, winning a California U.S. Senate seat.

Ronald Reagan had been movie actor in the 1930s and 1940s, appearing in variety of films, and also became a familiar 1950s TV host for the popular “General Electric Theater.” Reagan’s second wife, Nancy, had also appeared in Hollywood films. In addition to Reagan and Murphy winning office, one of Hollywood’s most notable childhood stars from the 1940s, Shirley Temple, ran for an open seat in Congress in 1967, but did not win. Still, by the time of the 1968 presidential election, with Ronald Reagan as California’s governor and George Murphy in the U.S. Senate, Hollywood and its celebrities were clearly a presence in Republican politics. But among the candidates for the Republican presidential nomination that year, was the very “un-Hollywood” former Vice-President, Richard M. Nixon.

Nixon’s Rise

Nixon cheering himself over election returns in 1950 in defeat of Democrat Helen Gahagan-Douglas in U.S. Senate race.

Nixon first made his way onto the national scene in 1946, elected as a Congressman from California. In Washington he quickly made a career for himself in the late 1940s as a member of the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), which pursued alleged communists in government and in Hollywood. Although Nixon became known for his role in the Alger Hiss case — a State Department official accused of being a Soviet spy — he also helped HUAC query Hollywood actors and executives suspected of communist activities or lacking in their loyalties. In 1947 hearings, for example, he asked Jack Warner of Warner Brothers, “How many anti-communist movies have you made?”

George Murphy, shown here with Shirley Temple in 1938, helped Richard Nixon in his bid for the White House in 1960, and became a U.S. Senator himself in 1964.

As a young Congressman and then a Senator, Nixon rose quickly in the Republican party, becoming Dwight D. Eisenhower’s vice-presidential running mate in 1952 (though Nixon did have one brush with controversy that year nearly costing him his career; see “Nixon’s Checker’s Speech”). The Eisenhower/ Nixon ticket, in any case, won two successive terms — 1952 and 1956. But when Nixon ran for President in 1960, opposing John F. Kennedy, he lost. Then in 1962, he tried to become California’s Governor and lost again, this time to Democrat Pat Brown. In each of these elections, from the early 1950s, there was always some contingent of Hollywood — both actors and studios — supporting Nixon and/or the Eisenhower/Nixon ticket. Nixon first met entertainer Bob Hope in the 1950s when Nixon was Vice President. Hope would become a friend and supporter thereafter. In 1960, when Nixon ran for the White House, Hollywood stars George Murphy and Helen Hayes formed a “Celebrities for Nixon Committee.”

Nixon had met Bob Hope in the 1950s when he was Vice President with Eisenhower. Hope became a Nixon supporter, and is shown here in September 1969 with President Nixon in the Oval Office.

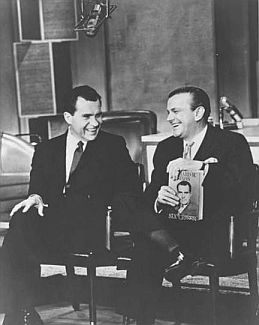

Nixon on Jack Paar TV show, believed to be March of 1963. Parr is holding Nixon’s book, ‘Six Crises,’ published in 1962.

Loss to Pat Brown

But after Nixon lost badly to Pat Brown in the 1962 California Governor’s race — by nearly 300,000 votes — he charged that the media had showed favoritism to Brown. Many pundits at the time thought Nixon was finished as a politician, especially since he declared the day after his loss: “You won’t have Nixon to kick around anymore because, gentlemen, this is my last press conference.” But several months later, Nixon appeared on The Jack Paar Program, (a talk show similar to that of today’s David Letterman or Jay Leno ) leaving the door open to his political future.

And sure enough, by the mid-1960s, Richard Nixon was rising from the ashes of his prior losses, on his way to one of the biggest political comebacks in American history. Nixon joined a New York law firm after his California gubernatorial defeat, and from there laid the groundwork for his return. He campaigned vigorously for Republicans in the 1966 Congressional elections, providing a key base of indebted members. Republicans added 47 House seats in that election, three in the Senate, and eight governorships. Nixon was also traveling and advancing his ideas on national politics and international affairs among Republican insiders. So it was no surprise to party regulars in January 1968, when he formally announced his candidacy for the Republican presidential nomination.

Romney, Rocky & Reagan

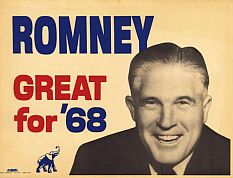

In some 1967 polling, Michigan Governor George Romney, a former auto company executive, led Nixon among moderates.

Nelson Rockefeller, shown on Time’s Aug 1960 cover, had previously battled Nixon for the nomination and lost.

In the first primary of 1968 — New Hampshire on March 12th, now without Romney — Nixon took 78 percent of the vote. Republicans wrote in the name of then yet-to-announce Rockefeller, who received 11 percent of the vote.

Rockefeller became something of a reluctant candidate, but allowed party members and others to work on his behalf. And eventually, Rockefeller did get into campaign mode, putting forward a plan to disengage from Vietnam and also offering some novel Republican strategies to address urban problems. But throughout the 1968 primary season, Nixon generally led Rockefeller in the polls, although Rockefeller won the April 30th Massachusetts primary.

The other Republican candidate then on the horizon, and a potential problem for Nixon, was filmstar-turned-politician Ronald Reagan.

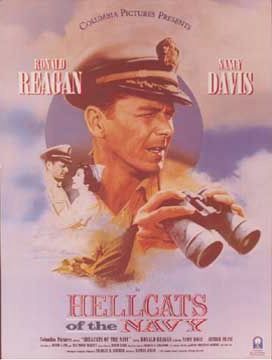

Ronald Reagan and Nancy Davis star in 1957's ‘Hellcats of the Navy,’ by Columbia Pictures.

By 1968, with support from conservatives, Reagan emerged as a potent challenger to Nixon. According to Gene Kopelson, author of Reagan’s 1968 Dress Rehearsal: Ike, RFK, and Reagan’s Emergence as a World Statesman (2016), Reagan at the time was being mentored, in part, by President Eisenhower, and he actually viewed Democrat Robert F. Kennedy as his main potential political rival. During his 1968 bid, Reagan first raised the issues he would pursue in his later presidency – tearing down the Berlin Wall, proposing an antimissile defense shield, and pushing for freedom behind the Iron Curtain. During the 1968 contest, Reagan had campaign staff across the nation, and he focused on the Wisconsin, Oregon, and Nebraska primaries. In the Nebraska primary of May 14th, he was Nixon’s chief rival. Still, Nixon took 70 percent of the vote there to 21 percent for Reagan, and 5 percent for Rockefeller. Nixon continued to win the primaries, with the exception of California, which he conceded to Reagan — a primary in which only Reagan’s name appeared on the ballot.

Reagan’s large margin in California, however, gave him a narrow lead in the nationwide primary popular vote — Reagan had 1,696,632 votes or 37.93% compared to Nixon’s 1,679,443 votes or 37.54%. Some believe that if Reagan had made a committed run for the nomination, and had mounted a more determined campaign earlier, he could have beat Nixon. Still, by the time the Republican National Convention assembled in August 1968, Nixon had 656 delegates, needing only 11 more to reach the nomination at 667. Author Gene Kopelson notes, however, that many delegates were obligated to Nixon on the first ballot, but could not wait to vote for Reagan had Nixon been stopped.

Celebrities for Nixon

Nixon shown here with Rudy Vallee in the 1960s. Vallee had been a well known radio and Hollywood film star of the 1930s & 1940s.

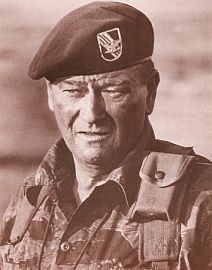

John Wayne’s movie, ‘The Green Berets', was released in July 1968.

John Wayne

Wayne had backed Nixon over Kennedy in the 1960 presidential race, and in 1968 he was backing Nixon again. Wayne liked Nixon for his anti-communist stance. A supporter of the Vietnam War, Wayne was a critic of Lyndon Johnson’s handling of the War. Wayne had made a popular war movie at the time that used Vietnam — a very patriotic film called The Green Berets (June-July 1968). The film had a premier in Atlanta, Georgia on June 25, 1968, which coincided with that city’s “Salute To America” celebration. Wayne served as grand marshal in the parade, and the overall event attracted some 300,000 people. The Green Berets film, meanwhile, was cheered in the south, but protested in northern cities and university towns. Nixon’s campaign staff had noted Wayne’s appeal to blue collar voters and a certain segment of the white southern vote. One of Nixon’s campaign aides at the time, Kevin Philips, explained Wayne’s appeal to a segment of voters Nixon needed: “Wayne might sound bad to people in New York,” he said, “but he sounds great to the schmucks we’re trying to reach through John Wayne — the people down there along the Yahoo Belt. If I had time I’d check to see in what areas The Green Berets was held over [in theaters], and I’d play a special series of John Wayne [Nixon campaign] spots wherever it was.” Wayne was also scheduled to speak at the Republican Convention in Miami that August.

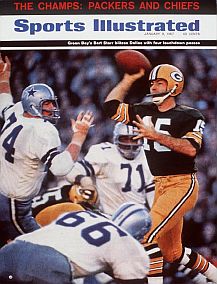

Green Bay Packer quarterback Bart Starr – shown on a ‘Sport Illustrated’ Jan 1967 cover – was a Nixon supporter in 1968.

Bart Starr & Wilt

Among other Nixon supporters were famous athletes, including, former heavyweight boxing champ Joe Louis, Los Angeles Lakers basketball star Wilt Chamberlain, and Green Bay Packer quarterback Bart Starr. Joe Louis was long retired from the boxing ring by then, but his name was still well known to sports enthusiasts. Bart Starr was probably the most famous professional football player in the country at the time. He had led the Packers to NFL Championships in 1961, 1962, 1965, 1966, and 1967. In 1966 and 1967, he also led the Packers to convincing victories in the first two Super Bowls and was named the Most Valuable Player of both games.

Pro basketball player Wilt Chamberlain — the LeBron James and Shaqueal O’Neill of his day — was nearly ten years into his career by then, and had played for the Harlem Globetrotters, the Philadelphia/San Francisco Warriors, and Philadelphia 76ers. He would help Nixon reach out to the black community and tout Nixon’s ideas on “black capitalism.”

Tex Ritter, who sang the famous 1952 movie song, ‘Do Not Forsake Me Oh, My Darlin’, was a Nixon supporter in 1968.

Tex Ritter

Another Nixon supporter in 1968 was Tex Ritter, a singing cowboy who began a radio career in the late 1920s, and also had success with stints in radio, film, Broadway, and recording. Ritter, father of the late actor John Ritter, was also known for singing the famous High Noon film song of 1952, “Do Not Forsake Me Oh My Darlin.” It won an Academy award for Best Song of the year and also became a popular hit. Ritter sang the High Noon song at the Academy Awards ceremony in 1953, the first to be televised. By 1968, Ritter had also become quite active in Republican politics, supporting the runs of various candidates including, John Tower of Texas, Howard Baker of Tennessee, George Murphy of California, Barry Goldwater of Arizona, and Ronald Reagan in California. A personal friend of Nixon’s, Ritter also wrote a campaign song for Nixon in 1968. On one occasion when Ritter was on tour in Germany, Nixon arranged for a plane to meet Ritter and his wife so that Ritter could entertain a political gathering being held for Nixon in Nashville, Tennessee where nearly 25,000 supporters were gathered. Nixon would also garner the support from Roy Ackuff of the Grand Ole Oprey.

Republican convention in Miami, August 1972, where Nixon was nominated on the first ballot.

Miami Convention

On August 5, 1968 at the opening of Republican National Convention, Miami Beach Convention Center in Miami Beach, Florida, there were mini-skirted Rockefeller girls, Nixon men on stilts costumed as Uncle Sam, and live elephants out in the street. Celebrities such as Hugh O’Brien and John Wayne were on hand too. On the first morning of the convention, delegates cheered enthusiastically as John Wayne spoke. Nelson Rockefeller, technically still in the running at that point, had his celebrities, too — among them, Kitty Carlisle, Teresa Wright, Nancy Ames, Hildegarde, and singer Billy Daniels. On the evening of August 7th, 1968, an estimated guest list of some 8,000 were wined and dined at a Nelson Rockefeller reception. Lionel Hampton’s band provided music, and among the guests were hundreds of celebrities.

John Wayne adressing convention.

Ronald Reagan threw his full support to Nixon at the 1968 convention.

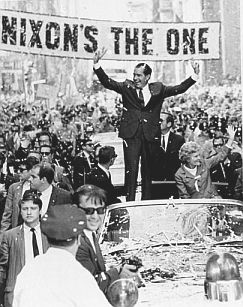

Nixon campaigning in the Philadelphia, PA area, July 1968.

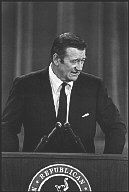

The Celebrity Preacher

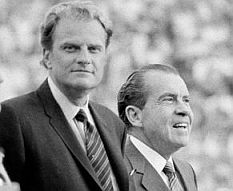

Another prominent American who had the ear of the middle America, and was also a supporter of Richard Nixon in 1968, was evangelist Billy Graham. Graham was a very popular religious leader with a huge following. A long-time friend of Nixon’s, Graham had prominently supported Nixon over Kennedy in the 1960 presidential election. In the 1950s, he had also supported Eisenhower. When Nixon was Vice President, Graham arranged for Nixon to address major gatherings of Methodists, Presbyterians, among others, and wrote at least one speech for him, according to Garry Wills.Billy Graham’s huge popu- larity in the south was seen as especially helpful to Nixon’s “Southern strategy.” “Graham worked closely with Nixon in the 1968 campaign, advised him on relations with the Evangelical community, and vouched for him in that community,” explains Wills in his book Head and Heart: American Christianities. Graham’s huge popularity in the south, in particular, was regarded as especially helpful to Nixon’s “Southern strategy” in 1968, a bid to appeal to conservative white Democrats in southern states, many still fearful of racial desegregation. Although Graham had desegregated his own religious activities in the South during the 1950s, he denounced civil rights agitators in the 1960s. His endorsement of “law and order” fit nicely with Nixon’s plan to attract Southern whites to the Republican side by denouncing liberal activists.

Billy Graham & Richard Nixon, 1970.

Connie & Jackie

Popular singer Connie Francis, shown here on an album cover, made a TV ad for Nixon in 1968.

Jackie Gleason, popular in his 1950s ‘Honeymooners’ TV sit-com, shown here in the 1961 film ‘The Hustler.’

In the fall of 1968, Jackie Gleason, the TV entertainer and film actor — making his first endorsement in national politics — threw his support to Richard Nixon. Gleason was the star of The Jackie Gleason Show and The Honeymooners, both of which were popular TV shows of the 1950s and early 1960s. Gleason had also made a few movies by then, including The Hustler of 1961, in which he played opposite Paul Newman as pool shark Minnesota Fats. ( Newman had supported Democrat Eugene McCarthy). Gleason in 1968 was still a popular celebrity and had a following throughout the country.

In the fall campaign, Gleason kicked off a one-hour long televised rally for Nixon from New York’s Madison Square Garden on October 31, 1968. He introduced the hour with his personal endorsement of Nixon, stating on the tape it was his first ever political endorsement as he made his appeal to voters.

On the tape, after a narrator introduces Gleason — who is dressed in a dapper suit with a carnation in his lapel — he makes his pitch:

Nixon with Jackie Gleason on golf course.

“I love this country. It’s been good to me — beyond my wildest dreams. And because I love America so much, lately I’ve been concerned. Like a lot of you, I’m concerned about where American is going in the next four years. That’s why I’ve decided to speak up for Richard Nixon. He sees it like it is. And he tells it like its is. I’ve never made a public choice like this before. But I think our country needs Dick Nixon — and we need him now. I think we’ll all feel a lot safer with him in the White House.

In the next hour, you’re going to see him, hear him speak. Listen to him. Make up your own mind. Never mind what everybody else tells you he says. Listen to him say it, yourself. And see if you don’t agree with me. Dick Nixon’s time has come. We need him. You and I need him. America needs him. The world needs him. …And so Madison Square Garden, ‘a-wa-a-a-y we go!’.”

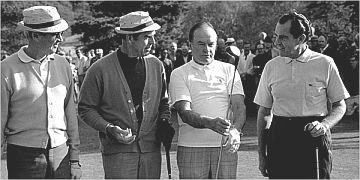

Richard Nixon with Jimmy Stewart, Fred MacMurray, and Bob Hope at Burbank, CA Lakeside Golf Club in January 1970. (AP photo)

In addition, both were avid golfers, and Gleason would have Nixon as a guest at some of his later celebrity and charity golf tournaments.

During his Presidential years, Nixon would also play golf with Hollywood celebrities from time to time.

T.V. Strategy

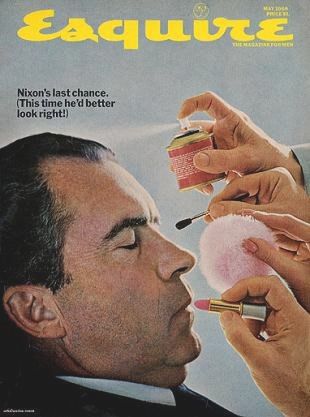

Esquire’s May 1968 cover had some fun with a stock Nixon photo mixed with some cosmetics ad copy. ‘This time he’d better look right,’ said the cover note, alluding to Nixon’s poor showing vs. JFK in 1960. Nixon did not debate Humphrey in 1968 and held few press conferences.

“Sock it To Me”

Nixon did, however, make one notable TV appearance in the 1968 election; an appearance on one of the more popular TV shows of that day — Laugh-In. Formally known as Rowan and Martin’s Laugh-In, the comedy and variety show was something like the Saturday Night Live of its day, though more of a fad show. But it was quite popular among the young. It offered witty skits and political barbs, and made stars of Goldie Hawn and Lily Tomlin. But most importantly for advertisers and politicians, Laugh-In had a very good rating, with millions watching. In mid-September 1968, Nixon broke from his general election campaign to appear on the show and recite the show’s signature catchphrase, “sock it to me,” often done by noted celebrities. Some believe that Nixon’s ‘sock-it-to-me’ appearance on Laugh-In helped him win the election, as it cast the otherwise formal and stodgy Nixon in a few seconds of self-deprecat- ing humor. Nixon’s taped appearance ran on September 16, 1968. Nixon himself had been reluctant to do the spot, not being a big fan of TV to begin with. And most of his aides were not very keen on the idea either, and advised against it. But one of the show’s writers, Paul Keyes, was a friend of Nixon’s, and when Nixon was out in California for a press conference they took a camera and got him aside to do the phrase. But it wasn’t easy. It took several takes. Nixon kept saying the phrase in an angry tone. Finally, Nixon did the line as a question, “Sock it to me?, with emphasis and uptick on the “me.” That was the version used, and the producer thought it made Nixon look good — so good, in fact, they thought Hubert Humphrey should appear on the show in an equal role. For Humphrey, they were thinking of using a variation of the phrase — “I’ll sock it to you, Dick” — as if responding to Nixon. But Humphrey’s handlers thought it would appear undignified, so Humphrey did not appear. Happily for Nixon, his Laugh-In appearance may have helped him in the election. Some believe that the brief clip had cast the otherwise formal and stodgy Nixon in a few seconds of self-deprecating humor. Even Humphrey would later tell the show’s producer that not making the appearance on Laugh-In might have cost him votes in the election. Nixon would also make an appearance with Laugh-In’s Dan Rowan and Dick Martin at a campaign stop in Burbank, California in October 1968 (see photo at beginning of story above).

Nixon campaigning in Philadelphia, PA, on Chestnut Street, September 1968. (AP photo).

Nixon Wins

On election day that November, in one of the closest elections in U.S. history, Nixon beat Humphrey by a slim margin. Although Nixon took 302 electoral votes to Humphrey’s 191, the popular vote was extremely close: Nixon at 31,375,000 to 31,125,000 for Humphrey, or 43.4 percent to 43.1 percent. Third party candidate George Wallace was a key factor in the race, taking more votes from Humphrey than Nixon, hurting Humphrey especially in the south and with union and working class voters in the north. Wallace recorded 9.9 million votes, or 13.5 percent of the popular vote, winning five southern states and taking 45 electoral votes. Democrats retained control of the House and Senate, but the country was now headed in a more conservative direction.

In his victory, Nixon brought some of his famous friends along with him to celebrate at the inaugural festivities. And beyond that, a few also made it into the realm of policy and received formal appointments. Shirley Temple Black was appointed by Nixon to be U. S. Representative to the United Nations. Other of Nixon’s famous friends became informal advisors and helped set a new cultural and even moral tone in the country.

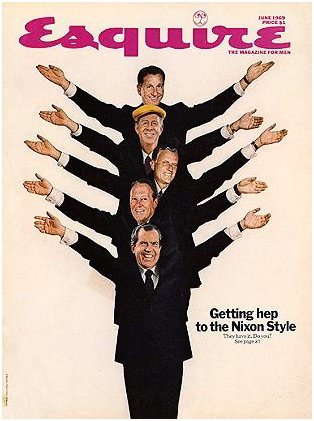

Esquire magazine ran a June 1969 cover story on ‘the Nixon style’ featuring his celebrity friends (behind Nixon): Art Linkletter, Billy Graham, Rudy Vallee & Lawrence Welk.

In June 1969, Esquire magazine poked fun at the new “Nixon style” in Washington with a cover story depicting Nixon supporters Lawrence Welk, Rudy Vallee, Billy Graham, and Art Linkletter along with Nixon himself for the story, “Getting Hep to the Nixon Style.”

Nixon would subsequently win re-election in November 1972, crushing Democrat George McGovern. But the Watergate scandal — which began as a back-pages, police-blotter news story about a bungled break-in at the Democrat’s Washington, D.C. headquarters — was already in motion. Watergate would soon unravel to become a full-fledged national scandal that would shake the federal government to its core, bringing Nixon to impeachment and then resignation as President in August 1974. Meanwhile, back in California where Nixon’s career had begun, there were those who remembered the 1940s and 1950s, and proudly sported a popular bumper sticker during the Watergate years that read: “Don’t Blame Me, I Voted for Helen Gahagan-Douglas!”

Other Richard Nixon stories at this website include: “Nixon’s Checkers Speech, 1952” (during which the Vice President extricates himself from scandal through the “magic” of television); “The Frost-Nixon Biz”(covering the famous 1977 David Frost-Richard Nixon TV interviews and the related book, stage, and film productions that followed); and “Enemy of the President” (about cartoonist Paul Conrad and some of his famous Nixon Watergate cartoons). Nixon is also covered in part in, “JFK’s 1960 Campaign,” as well as “The Pentagon Papers, 1967-2018,” where the seeds of Watergate were first planted. See also at this website, the Democrats’ 1968 story at, “1968 Presidential Race – Democrats.” Thanks for visiting – and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research and writing at this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

___________________________

|

Please Support Thank You |

Date Posted: 11 March 2009

Last Update: 6 March 2018

Comments to: jdoyle@pophistorydig.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “1968 Presidential Race, Republicans,”

PopHistoryDig.com, March 11,2009.

______________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

Murray Schumach, “Producer Plans Drive for Nixon; Mervyn LeRoy, Heading the G.O.P. Hollywood Push,”New York Times, Tuesday, August 23, 1960, p. 26.

Murray Schumach, “Hollywood Slate; Luminaries Come to the Aid of Their Parties in the Presidential Race,” New York Times, Sunday September 25, 1960, p. X-9.

Murray Schumach, “Hollywood Joins Political Battle; Stars Jump on Bandwagons in Brown-Nixon Contest,” New York Times, Monday, September 17, 1962, p. 37.

“The Brainwashed Candidate,” Time, Friday, September 15, 1967.

Chris Bachelder, “Crashing The Party: The Ill-Fated 1968 Presidential Campaign of Governor George Romney,” Michigan Historical Review, September 22, 2007.

Warren Weaver, “M’Carthy Gets About 40%, Johnson and Nixon on Top in New Hampshire Voting; Rockefeller Lags,” The New York Times, Wednesday, March 13, 1968, p. 1.

Louis Calta, “Entertainers Join Cast of Political Hopefuls; They Get Into Act to Back 3 Candidates for the Presidency,” New York Times, Saturday, April 6, 1968, p. 42.

Associated Press, “Celebrities Endorse Candidates,” Daily Collegian (State College, PA), May 5, 1968.

“NFL Quarterbacks Head Busy Day for Athletes,” The Washington Post, Times-Herald, May 23, 1968, p. C-9.

“Wilt Chamberlain for Nixon,” New York Times, Saturday, June 29, 1968, p. 30.

Tom Wicker, “Nixon Is Nominated on the First Ballot,” New York Times, Thursday, August 8, 1968, p. 1.

“Wilt Chamberlain Will Push ‘Black Capitalism’ Program,” New York Times, Thursday, August 8, 1968, p. 30.

Robert J. Donovan, “GOP Names Nixon on First Ballot,” Los Angeles Times, August 8, 1968, p. 1.

Don Irwin, “Nixon Comeback Had Its Start in Ashes of 1964 GOP Debate, Los Angeles Times, August 8, 1968, p. 1.

“Chamberlain to Aid Nixon’s Slum Program,” Los Angeles Times, August 8, 1968, p.10.

“Nixon Image Defended; Billy Graham Blasts Ball,” St. Petersburg Times, Monday, September 30, 1968, p. 10-A

UPI, “Billy Graham Says Nixon Is Not ‘Tricky’,” The Washington Post, October 1, 1968, p. A-4.

“Nixon Gets Quasi-Psychedelic Plug,” New York Times, Wednesday, October 9, 1968, p. 33.

Thomas J. Foley, “Politicians Take Cue From Show Business; Nixon, Humphrey Both Use Panel Shows, Documentaries in Biggest TV Campaign, Los Angeles Times, October 6, 1968, p. A-16.

For 1968 campaign ads, see Museum of the Moving Image, “The Living Room Candidate: Presidential Campaign Commercials: 1968.”

Gary A. Yoggy (ed.), Back in the Saddle: Essays on Western Film and Television Actors, 1998, McFarland & Company, Inc., 1998, 224pp.

Norman Mailer, Miami and the Siege of Chicago, Weidenfeld and Nicolson,1968.

Garry Wills, Head and Heart: American Christianities, New York: Penguin Group, 2007.

Nancy Gibbs and Michael Duffy, Billy Graham: The Preacher and the Presidents: Billy Graham in the White House, Center Street, 2007.

Seth Dowland, “Judgment Days: Two New Books Find Good and Evil in the Rev. Billy Graham’s Presidential Politics,” Mountain Express, Vol. 14 / Issus 11, October10, 2007.

Cecil Bothwell, The Prince of War, Brave Ulysses Books, 2007.

Ann Heppermann & Kara Oehler, “This Weekend in 1968: Political Plays to the Silent Center,” American Public Radio, May 17, 2008.

“The Presidents Series: Richard M. Nixon,” American Experience, PBS/WGBH, 2002-2003.

____________________________________________