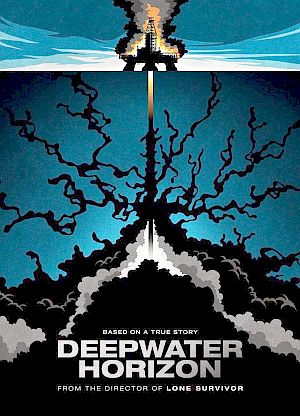

DVD cover for 2016 film, "Deepwater Horizon," based on the 2010 BP Gulf of Mexico oil rig disaster that killed 11 workers and resulted in the worst oil spill in U.S. history. Click for DVD.

The real life BP oil spill of 2010 is mostly remembered as an environmental catastrophe – for the months-long oil hemorrhage spewing from the blown-out well 5,000 feet below the water’s surface.

The spill – the worst in U.S. history — lasted 87 days and spilled an estimated 4.9 million barrels (210 million gallons) of crude oil into the Gulf of Mexico. The damage to the region – from Texas to Florida – was extensive, taking a toll on wildlife, fisheries, tourism and more. BP paid out billions in fines and damages, and the full ecological toll is still being studied.

But one part of the Deepwater Horizon disaster that did not receive the media attention the spill did was what happened to the rig’s workers before the spill, when the well blew out and the rig became a raging inferno and death trap.

This is the story that the 2016 Hollywood film endeavors to tell with the aide of an all-star cast, including: Mark Wahlberg, Kurt Russell, John Malkovich, Gina Rodriguez, Dylan O’Brien, and Kate Hudson.

Turns out that making this film was no easy task. Director Peter Berg, producers, and studio faced some pretty stiff challenges, not least of which was a resistant Louisiana oil culture led by BP, local workers fearful or legally bound from not talking, and having to build an enormous offshore oil rig set that cost tens of millions (more on all of this later). Still, Berg, studio, cast and crew pulled it off in good form, producing an important film that is as much a cautionary tale and valuable history lesson as it is entertainment.

The Deepwater Horizon film focuses on the failed elements and decision making that led up to the 2010 BP blowout. It covers the mayhem of the initial catastrophe, the worker heroics attempting to right the ship, and the final scramble of workers to get off the doomed rig. It is a film “inspired by a true story of real life heroes,” as the film’s promotional material explains.

In fact, the Deepwater Horizon film is based, in part, on an account that appeared in print by New York Times reporters David Barstow, David Rohde, and Stephanie Saul. That 8,500 word story, run on the front page of the Sunday, December 26th, 2010 edition, was titled, “Deepwater Horizon’s Final Hours — Mixed Signals. Indecision. Failed Defenses. Acts of Valor.” It began as follows:

The New York Times story, “Deepwater Horizon’s Final Hours,” ran on the front page, Sunday, December 26, 2010.

“The worst of the explosions gutted the Deepwater Horizon stem to stern.

Crew members were cut down by shrapnel, hurled across rooms and buried under smoking wreckage. Some were swallowed by fireballs that raced through the oil rig’s shattered interior. Dazed and battered survivors, half-naked and dripping in highly combustible gas, crawled inch by inch in pitch darkness, willing themselves to the lifeboat deck.

It was no better there.

…Searing heat baked the lifeboat deck. Crew members, certain they were about to be cooked alive, scrambled into enclosed lifeboats for shelter, only to find them like smoke-filled ovens.

Men admired for their toughness wept. Several said their prayers and jumped into the oily seas 60 feet below….”

It was this New York Times story that Lionsgate and its partners, acquired for film rights to use as a starting point for the film. (However, the film’s casting, script writing, set construction, and filming would not be finished until 2016, and during that time there was more detailed information, continued news reporting on the BP catastrophe, as well as government and corporate inquires, a 60 Minutes program, and other information that could be used to help frame the film and its characters.)

Risky Business

Poking holes into underground geological strata holding fossil fuels is inherently risky business. Geological formations holding oil and gas are typically under great pressure. They hold various mixed proportions of volatile natural gas and oil. In the film, these inherent dangers are “set up” in a family scene at the home of Mike Williams (Mark Wahlberg) and his wife, Felicia (Kate Hudson), and their elementary school-age daughter, Sydney, who is doing a “what-my-Daddy-does-at-work” project.

Mike Williams (Wahlberg) in film scene at home with wife (Kate Hudson) and daughter Sydney before departing for his shift on the drilling rig, is about to use a shaken Coca-Cola can as “oil reservoir” to illustrate drilling well pressures.

Sydney correctly, if somewhat fantastically, describes the 300 million year old fossil deposits “where the trapped dinosaurs are” who want to be free and rush furiously to holes poked into their reservoirs. Her father uses a shaken can of Coca-Cola to illustrate the pressures involved, poking a hole in the can as his daughter then applies honey to the hole, simulating drilling mud, “to tame the dinosaurs.”

Floating oil rig in 5,000 ft of water; well on sea bed below.

Sydney Williams: My dad is Mike. He works on a drilling rig that pumps oil out from underneath the ocean. That oil is a monster, like the mean old dinosaurs that oil used to be. So for 300 million years, these old dinosaurs have been getting squeezed tighter and tighter and tighter and tighter.

Mike Williams: We get it. Just use two “tighters”.

Sydney Williams: Then dad and his friends make a hole in the earth. These mean old dinosaurs can’t believe it. Freedom! So they rush through the new hole. Then smack, they run into this stuff called mud that they cram down the straw [her pipe/riser in the Coke can] to hold the monsters down…

But during the end of this table-top demonstration – and as prelude to what actually happens later in the film on the Deepwater Horizon – the “well” in the Coke can sends up an uncontrolled geyser of “untamed dinosaurs.” It’s a clever little lesson, which serves to clue-in viewers of the bigger drama yet to come. Here’s the film trailer with the kitchen scene and the later, more explosive action.

Offshore oil rigs of the Deepwater Horizon variety are enormous and complex structures. On one level they are truly marvels of sophisticated engineering and oil industry “derring-do.” Since the early days of oil extraction when the first flimsy wooden rigs ventured a couple hundred yards offshore into shallow water, the business and technology of oil drilling at sea has become dramatically more capable and powerful. Today’s modern rigs – of nearly aircraft-carrier heft and proportion – are now able to go many miles out to sea and drill in 5,000 to 10,000 feet of water. Total well depth beyond that – i.e, from the sea floor, where the actual drilling begins, to the pay zone, where the oil is – can be 10,000-to-20,000 more feet. This was the case with the drilling at BP’s Macondo oil well prospect in the leased federal waters of the Gulf of Mexico about 45 miles south of Louisiana.

Sample offshore drilling rig shown here, with its main well derrick, construction cranes, and helicopter landing pad. This happens to be another Transocean rig. But for some perspective on the scale of things in the offshore world, note what appear to be two “tiny men” standing mid-deck on the supply boat, lower right corner of the photo.

The drilling rig involved, however, was not BP’s. This rig, owned and operated by Transocean, a Swiss company, was leased by BP to drill the well. Transocean and the Deepwater Horizon were hired by BP to drill and open the well, not extract the oil. Once drilled, BP would later move in a production rig or submersible pumping unit to harvest the oil. The disaster occurred, however, at BP’s well; Transocean was then attempting to finish the opening of the well. Both parties, however (plus a third party, Halliburton) each bore some responsibility for what went wrong when the well blew out, as later investigations would find that a series of bad decisions, corner cutting, and failed technology all contributed to the disaster.

What the film dramatizes, in part, is the conflict between BP’s man on the scene, Donald Vidrine (played by John Malkovich), and Transocean’s rig manager and safety guy, Jimmy Harrell (“Mr. Jimmy,” played by Kurt Russell). BP wants to get the job done quickly (i.e. to meet corporate goals and profit targets), while Transocean wants to get the job done safely (not injuring or killing any workers or fouling the environment). And in fact, in real life, at the time of the blow-out, the Transocean rig was six weeks behind schedule, costing BP half a million dollars a day, so there was no fiction about BP’s push to complete the well as fast as possible.

Transocean’s “Mr. Jimmy” – played by Kurt Russell, the man concerned with rig integrity & safety. |

BP’s Donald Vidrine, played by John Malkovich, the man concerned with $ 1 million-a-day drilling delays. |

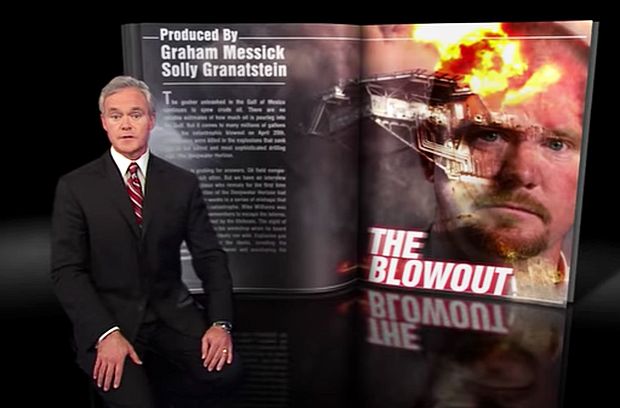

Mark Wahlberg’s Mike Williams is the lead character in the film. He is the person who frames the whole movie as he interacts with his family at home, Mr. Jimmy, BP’s Vidrine, and various workers on the drill floor and control bridge. (Williams in real life would later give 60 Minutes’ Scott Pelly an extensive and compelling interview recounting his harrowing ordeal on the rig during the catastrophe. More on this later).

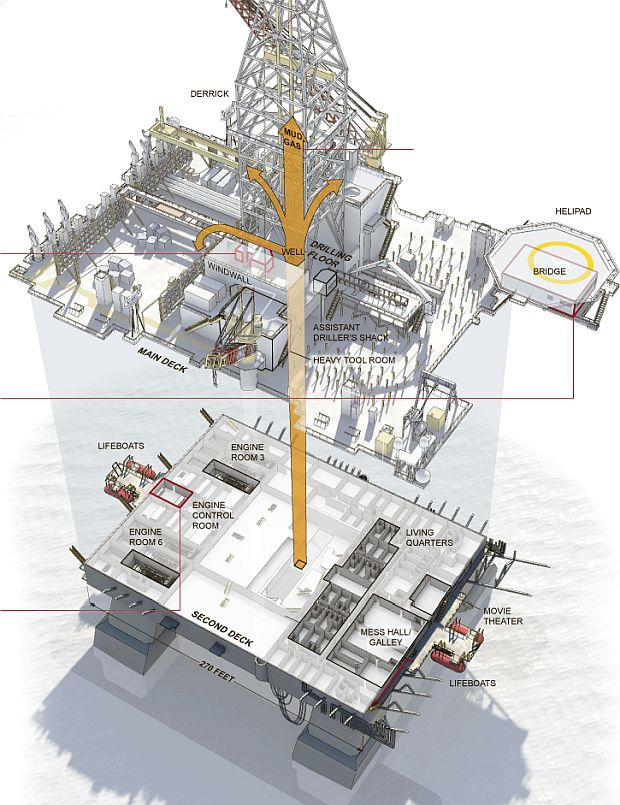

The film also does a good job of capturing the scale and sophistication of modern offshore drilling rigs. The Deepwater Horizon was known in the trade as a dynamically positioned, semi-submersible, mobile offshore drilling unit. That means, essentially it floats, albeit with the aide of some sophisticated technology, being “dynamically positioned,” or locked in one place, with the help of an assortment of data fed into its computers – wind sensors, motion sensors, gyro-compasses, etc.

Film clip, drilling rig derrick. Looking skyward, from the drilling floor of the main deck, up into the farthest reaches of a multi-story, steel-built drilling derrick at the center of the rig.

The Horizon’s main deck was nearly as big as a football field. And mounted at the center of that deck was the main attraction – a 25-story well derrick (above photo), made with tons of steel, and flanked by two large cranes. Below the main deck there were two floors. These included sleeping rooms for up to 146 people– as crew and officers lived on the rig for weeks at a time. Each room had its own bathroom and satellite television. On board, there was also a gym, a sauna, and a movie theater. Housekeepers cleaned the crew members’ rooms and did their laundry. Some workers called the place “a floating Hilton.”

A New York Times illustration of the Deepwater Horizon rig helps to show the gigantic rig's layout, with helicopter pad and bridge control center at top left, and various other levels, production cranes, engine rooms, drilling floor, and central well shaft area, as well as living quarters, mess hall, movie theater, and life boat areas. It also shows path of mud & gas during blow-out.

But the Deepwater Horizon rig was also about the business of opening new wells, and could carry up to 5,000 pieces of drilling equipment, pipe, and tools. The rig was ten years old at the time of the catastrophe, but still pretty much a state-of-the-art facility that included lots of redundant safety features. The rig won an award for its 2008 safety record, and on the day of the disaster, in fact, BP and Transocean managers were on board to celebrate seven years without a lost-time accident, which is depicted briefly in the film when Mr. Jimmy is given the award and cheered by the crew assembled in the mess hall.

Film clip. Mike and Felecia Williams in the family SUV, travel over Louisiana causeways and wetlands on their way to the regional heliport for Mike's departure to the offshore Deepwater Horizon drilling rig in the Gulf of Mexico.

Deepwater Horizon also captures the everyday life of rig workers and the environment of southern Louisiana’s oil culture. Early in the film, Wahlberg’s character travels with his wife in the family SUV over some miles of Louisiana causeways and beautifully green wetlands to the regional helicopter center that ferries hundreds of workers back and forth to the numerous rigs out in the Gulf. There are dozens of copters at this field awaiting others crews, as the Deepwater Horizon group in the film is shown walking to their designated departure pad (In 2013, BP reported that some 12,000 people each month traveled through the Houma, LA heliport on their way to BP rigs and platforms in the Gulf of Mexico).

Mark Wahlberg’s Mike Williams character (right) walks with Mr. Jimmy (Kurt Russell, left), bridge officer, Andrea Fleytas (Gina Rodriguez, center), and other crew on their way to waiting helicopter for the 45-minute flight to Deepwater Horizon rig.

At the heliport, Williams has joined his colleagues, including: Andrea Fleytas (played by Gina Rodriguez), a young bridge officer in charge of the rig’s sophisticated navigation computer; Transocean crew chief, “Mr. Jimmy” (Kurt Russell); two BP executives; and others. They will take a 45 minute helicopter flight out to the rig. (Of the helicopter ride out into the Gulf, the film’s director, Peter Berg, who took a similar trip, would later observe: “I did one of these flights out to a rig. And you get about 5 miles out and you still have 35 miles to go. And you hit weather, you know, there’s a lot of weather in the Gulf. And the isolation is very clear and very palpable. And I found… my anxiety level after about 5 miles, [and] every mile, I just felt unsettled and very alone in that helicopter.” And in the film, during the helicopter ride, there is a bird strike, which brings a brief moment of distress to the passengers.

Film clip showing helicopter with about a dozen BP and Transocean passengers aboard, approaching Deepwater Horizon rig.

Upon arrival on the rig’s helipad, Williams and Mr. Jimmy notice that the well cementing crew is boarding the helicopter for the return trip back to land, claiming they’ve finished their work, as the BP guy, Donald Vidrine (Malkovich), has said that no further testing was needed. But Mr. Jimmy is distressed by this claim, as he believes checking the integrity of completed cement work on the well – called a “cement bond log”– is critical for the rig’s safety. So Mr. Jimmy sets about verifying from several sources on the rig, with the help of Mike Williams, that yes, in fact, BP has passed on verifying the cement work. Mr. Jimmy has also noticed a boat in the area, the Damon Bangston, and verifies it too has been summoned by BP to take on drilling mud, another verification that BP has by-passed the testing. This prompts Mr Jimmy and Mike to go visit with BP’s Donald Vidrine and other BP officials in their on-rig office, where they have a somewhat testy exchange about the cement work. Mr. Jimmy, reminding the BP folks that a properly done cement job “is the only thing between us and a blow out,” says it would only cost BP $125,000 to do it properly. Vidrine replies that Transocean is 53 days being behind schedule, costing BP millions. Mr Jimmy, who has the final word on rig procedures, insists that a negative pressure test be done, which is reluctantly agreed to by the BP folks.

Film clip of Mr. Jimmy watching monitors as negative pressure testing in underway, with Mike Williams (far right), BP’s Donald Vidrine (obscured in back), and other Transocean crew.

As they gather to monitor the test, there are some anxious moments as the computer monitors record steadily rising well pressure – 100 psi (pounds per square inch), 450 psi, 900 psi, 1395 psi – “enough to cut your car in half,” says Mr. Jimmy on that last reading, and at which point “pressure alert” warnings are also sounding. But Vidrine, drawing on a whiteboard to make his point, dismisses these as an anomaly or false readings, claiming that sensors are picking up “pockets of pressure,” also explained in technical jargon as a “bladder effect.” Still, Mr. Jimmy is not assured and wants further testing. Vidrine then agrees to run a second test, this time on the “kill line” to illustrate his belief they are over-reacting to the first test.

Mr. Jimmy, meanwhile, is called away at that point by two other BP officials for an “urgent safety matter” on another deck, which is pretext for presenting him with a safety award in front of assembled crew in the galley. On his way to the safety gathering, Mr. Jimmy and Mike acknowledge that it’s possible Vidrine’s theory about the pressure test could be correct, but they still have their doubts. Mr. Jimmy, meanwhile, is lauded at the surprise gathering for his safety leadership. Back at the kill line test, however, the readings are still not stellar, and Mr. Jimmy’s Transocean colleague, Jason, is reluctant to give BP’s Vidrine the o.k. until he talks to Mr. Jimmy. Over the intercom, Jason informs Mr. Jimmy of the barely passable results. Mr. Jimmy very reluctantly gives the o.k., and tells Jason he will see him in about a half an hour. He decides to go to his room for a quick shower and some rest before resuming his duties. Vidrine then issues the go ahead to begin pumping out drilling mud, on the way to completing the well opening and closing out that phase of the work.

Film clip. On the drilling floor of the Deepwater Horizon, with well at work at left, floorhand Caleb Holloway (Dylan O’Brien) holding radio speaker, is in communication with the drill operator in the wire-protected Drill Shed behind him, as BP’s Donald Virdrine (John Malkovich) looks in at the well shaft. Things appear to be working O.K.

Donald Vidrine’s gamble appears to work, as the oil well seems to be cooperating with no adverse signs. Mike Williams by this time is back at his workshop office, later talking with his wife on a computer screen over Skype. On the drilling floor, work on the well resumes with the Transocean crew, as BP’s Virdrine walks by occasionally to monitor the work.

However, as the drilling crew is going about their work, floorhand Caleb Holloway (Dylan O’Brien) notices a tiny bit of mud welling up around the drill pipe. It also starts coming up in the seams around the well drilling floor.

Film clip. Floorhand Caleb Holloway (Dylan O’Brien) discovers some bad news at the drill pipe.

“Are you seeing this?,” Holloway frantically calls into the drill shack monitor on his radio. And just then, a large buildup of mud gushes up through the pipe, causing it to burst, sending drill crew members and BP’s Vidrine flying off their feet, thrown about, and covered in a torrent of mud and spray from the powerful blowback.

Blast of mud and debris from the well sends workers flying on the Deepwater Horizon drilling rig.

After some struggle, the drill crew and technicians manage to stop the mud from spewing. But Jason in the Drill Shed is still recording rising pressure. Then, as popping bolts and projectiles begin pelting the Drill Shed, he calls for the crew “to get off the drilling floor — now !” But just then the rig shakes violently, and another, more powerful burst of mud and pressure spews, this time rising up through the top of the rig’s huge derrick. Rig floor workers struggle against the torrent, and their attempts at control are futile. Some begin a scramble to the lifeboats.

Film clip. Transocean floorhand Caleb Hollway (Dylan O’Brien) attempts to help BP’s Donald Vidrine (John Malkovich) to his feet after powerful well blast on the Deepwater Horizon rig.

Methane gas is part of the escaping blow-out brew and this volatile substance begins to seep out invisibly all over the rig. Some of the drenched workers can smell and taste the gas; a few begin to panic. Gas alarms are now sounding throughout the rig. Up on the bridge, Andrea is discovering that the rig’s giant underwater thrusters that maneuver the rig are over-revving as escaping gas is being sucked into their on-board engines. She can’t hold the rig in place. Magenta alarms – the most serious of the color-coded alarms – are going off and appearing on the consoles. The leaking gas soon finds an ignition source and a powerful explosion occurs, cascading destructively throughout the rig, and a roaring firestorm ensues.

Mike Williams (Wahlberg) in his workshop on a Skype call to his wife when he hears some strange sounds, moments before he is blown across the room behind the flying metal door of his workshop and knocked unconscious temporarily.

Mike Williams, then at his workshop office in conversation with his wife on Skype, hears a few pops and pings, and the lights suddenly get real bright. Just as he starts to get up to see what’s going on, the explosion sends him flying as the heavy steel door to his office is blown off its hinges, sending him across the room and to the ground.

Mr. Jimmy, meanwhile, is then in the midst of his shower. As the terrific blast force ripples through the living-quarters, compressing those compartments as it goes, Mr. Jimmy is blown against the shower wall and bounced out onto the bedroom area like a rag doll. He is knocked out temporarily and lands on the floor. A blast wave of tiny glass, metallic, and plastic particles have hit him and now cover his entire body.

Mr. Jimmy, showering in the living quarters, notices the lights becoming brighter; not a good sign. As a blast wave rips through the living quarters, Mr. Jimmy is bounced around his compartment like a rag doll, covered with debris, and is temporarily knocked out.

Mr. Jimmy, upon waking in near darkness, and now with impaired vision, discovers that a long slender piece of glass or metal has pierced through the arch of his foot and is lodged there. He pulls it out with a painful scream. He then pulls on some coveralls and shoes, cursing at the pain. Feeling his way along the walls, he tries to walk, but falls down in a near hallway.

Mike Williams, too, is in a post-blast daze. He wakes up with a door on top of him, pushes it off, and manages to make his way to a hallway with a flashlight, where he finds an injured colleague who he helps to the lifeboat area. He then decides to go to the living quarters to look for Mr. Jimmy.

Mark Wahlberg’s Mike Williams character shown with flash light and crow bar at left, and Mr. Jimmy next to him, trying to free trapped worker whose leg is stuck and severely injured between damaged deck flooring.

When Mike arrives at the living quarters area, he finds Mr. Jimmy on the floor in a hallway and helps him up to walk. Mr. Jimmy asks Mike to help get him to the bridge to check on the status of the well. But along the way they hear calls for help from a pair of workers, one with his leg caught between heavy steel plates. They work to help free him, buffeted by a secondary blast as they do.

With the Deepwater Horizon now in flames, the nearby Damon Bangston work vessel has also sent in a “may day” call: “the Deepwater Horizon has exploded and is on fire.” The Bangston is the one refuge ship in the area, and it sends out a smaller skiff to look for survivors.

As the Deepwater Horizon burns in a raging inferno, the nearby Damon Bangston vessel sends out a smaller rescue boat to help pick up survivors.

The film cuts briefly to U.S. Coast Guard message center where other reports of an explosion in the Gulf are also coming in, which the Coast Guard verifies and locates with a satellite image that shows the burning rig. Rescue helicopters are dispatched, but it will take more than 35 minutes for them to get to the rig.

Film clip. At the home of Mike Williams, Felicia has learned that there is a fire on the Deepwater Horizon, and that some workers are “jumping into the water”.

At the home of Mike Williams, Felicia has called the company to learn that there is a fire on the Deepwater Horizon, but she is given no further information. She has also called the wife of another rig worker who has learned that some workers “are jumping into the water.” Felicia fears the worst for Mike.

Back on the rig, Mr. Jimmy says he must get the bridge, as he and Mike continue their trek through flames and flying debris. Arriving at the bridge, Mr. Jimmy has a long “if-looks-could-kill” face-off with BP’s Vidrine, curtly ordering him to the lifeboats.

Film clip. At the bridge control center as the rig continues to burn, Mr. Jimmy and BP’s Donald Vidrine have an awkward moment, but Mr. Jimmy contains his anger and orders Vidrine to the lifeboat area.

At the bridge, Mr. Jimmy, asks for Andrea’s help to guide his hand to the disconnect button on the control panel to activate the blowout preventer on the sea floor below to cut the riser pipe and seal the well. But it doesn’t work. They try a second time. No dice. Mr. Jimmy then decides they must try to hold the rig in place so the riser pipe doesn’t break off without a seal. But the rig is dead in the water; there is no power.

Mr. Jimmy says the emergency generators could work, but they’re on the other side of the rig, a perilous distance given the circumstances. Mike then volunteers to go across the rig to reach the emergency generators. Floorhand Caleb Holloway (Dylan O’Brien) volunteers to go with him. This journey is filled with continuing peril from fire, secondary explosions, and flying shrapnel all over the rig.

Mike Williams (Wahlberg) and colleagues find a worsening situation on the Deepwater Horizon rig as the rig fire intensifies and secondary explosions occur all around them.

Along they way, one of the huge cranes is swinging perilously above the rig, as it has broken free of its cradle. Mike and Caleb see one of their fellow workers scale the fiery tower to get to the operator’s chair attempting to bring the crane back to its cradle. He does so heroically, but soon falls to his death as the continuing inferno claims him.

Mike and Caleb get to the generators and start them briefly. For a moment, back on the bridge, Andrea and others are elated they have power to maneuver the rig, but the power goes out again. Back at the generators, Mike and Caleb try again, and start the generators a second time, successfully it appears, and they try heading back to the bridge across the blazing rig.

A badly beaten up Mr. Jimmy confers with others on the bridge about their worsening situation on the Deepwater Horizon.

Back on the bridge, Mr. Jimmy is flagging, nearly passes out, and is helped by Andrea. The situation on the rig has deteriorated badly by this time, and the captain gives the abandon ship order. Most of the crew have already made it to the lifeboats, and have evacuated the rig. The last of those on the bridge, including Mr. Jimmy, now head to the lifeboat area, only to discover that the last one has already left. Mike and others work to deploy a canister holding an inflatable emergency raft, and after some difficulty, are successful, though Caleb has caught fire and falls into the water during the process, but is shortly rescued.

Mike, Caleb, and others attempt to deploy an emergency raft cannister, their last chance of escape from the blazing Deepwater Horizon.

As conditions on the rig deteriorate in the area of the emergency raft, Mike and Andrea are cut off from the raft area by a small explosion, and are unable to board the raft. Instead, they will have to don life vests and jump into the water. However, they have to climb to a higher level on the rig amid the inferno in order that their jump trajectory will take them beyond flaming seas. They climb up to the helicopter pad level.

Andrea is terrified and refuses to jump, as Mike tries coaxing her. Still she hesitates, then Mike asks her a distracting question and pushes her off the rig with a little run assist. He then follows her with his own run and leap. They each plunge deep beneath the water, surfacing in the oily waters as some flaming seas can be seen not far from them. They are later pulled to safety in a rescue skiff, which heads for the Damon Bangston nearby.

Mike and Andrea contemplating their plight after being unable to board the last emergency escape raft, now have to don life vests and jump from the burning Deepwater Horizon rig into the waters below, much of which is also ablaze.

As they climb aboard that ship and find some space to collect themselves, they, like others, are shattered emotionally from the horror they have just experienced. Much of the evacuated crew has assembled on the deck of the Damon Bangston, where an injured Mr. Jimmy begins calling the roll to get an accounting of those who have made it. Evacuation helicopters come to take away the most seriously injured. After a time, the survivors on deck are led in a round of the Lord’s Prayer. The nearby Deepwater Horizon is still burning, and would continue to burn for two more days before it would sink to the sea floor more than 5,000 feet below.

Survivors from the Deepwater Horizon blow out and explosions have gathered on board the "Damon Bangston" vessel, here showing Dylan O'Brien's character, Caleb Holloway, at center.

The surviving crew is then taken away from the scene to hotels on land where they are given medical treatment and rooms to shower and reunite with their families. Mike is swarmed by reporters outside a hotel, and he is shoved against a wall by a distressed man asking him if his son got off the rig. Mike goes up to his room and breaks down as he tries to take a shower. Felicia and Sydney enter the room to comfort him in a family embrace. But throughout his ordeal, Mike has managed to hold onto the fossil he was given for Sydney, which he gives to her. Later, upon leaving the hotel, the camera pans Andrea and Caleb reuniting with their loved ones, while both Mike and Felicia embrace Mr. Jimmy, who is walking on crutches.

After the movie’s ending, the film continues with a tribute and homage to the eleven men who were killed on the Deepwater Horizon. There is also footage of the real Mike Williams, Andrea Fleytas, and James Harrell giving testimony in the aftermath of the disaster. Williams never returned to sea, and lives in Texas with his family. Fleytas lives in California and no longer works in the oil industry. James Harrell continued his work for Transocean. BP’s Donald Vidrine and Robert Kaluza (also portrayed in the film) were indicted on manslaughter charges, but federal prosecutors later dropped those charges.

Making The Film

“To this day, when people think of Deepwater Horizon, they only think of an oil spill,” said film director Peter Berg in 2016 comments to the Los Angeles Times, “– they think of an oil spill and dead pelicans,” said Berg. “Obviously that oil spill was horrific,” he continued. “But the reality is 11 men died on that rig and these men were just doing their jobs and many of them worked hard trying to prevent that oil from blowing out and it was certainly not their fault. As it pertains to the families of those men who lost their lives, I want them to feel as though another side of that story was presented, so that whenever someone talks about the Deepwater Horizon or offshore oil drilling, people don’t automatically go to ‘oil spills.’ ”

However, the families of the workers who were killed in the disaster were initially resistant to the film. “When Pete (Berg) and I reached out to the families we were getting resistance at first, and we didn’t understand,” said Wahlberg, also one of the film’s producers, in a USA Today interview. “I’ve done Lone Survivor [2013], I’ve done many true stories. We figured our reputation would have been enough to at least get us to be able to sit down (with them).”The families of the workers killed on the rig were afraid the film would again cause their loved ones to be blamed for the oil spill. The families, it turns out, were afraid that their loved ones would be blamed, again [as occurred in 2010], for the devastating environmental consequences of the massive oil spill that followed the disaster. But Berg and Wahlberg made clear to the families their intention was to highlight worker efforts to save the rig in doing their jobs, and helping save one another during the rig’s melt down. The film would also include coverage of rig safety measures cut by BP to speed up production – namely, skipping the check on the well cementing. Still, to be sure that they got the story as correct as possible from the workers’ perspective, as well as the work settings used in the film, they signed on Mike Williams as a consultant to the film. “Once I met Mike,” Wahlberg explained, “I just insisted that they bring him on as a consultant. I wanted him to be there with us and make sure we were getting it as accurately as possible.” Caleb Holloway was also consulted. Once Berg and Wahlberg communicated their intent to the families, they had their support for making the film.

May 2010. The CBS TV show, "60 Minutes," aired a riveting interview with Mike Williams, which recounted his harrowing escape from the rig. The interview also helped frame Williams’ role in the film. Click for DVD.

Williams had also given a riveting 2010 interview with Scott Pelly on the CBS 60 Minutes program in which he recounted his harrowing escape from the rig. That interview also helped frame the Williams role in the film.

In making the film, there was also considerable attention to detail on the set, not the least of which was the enormous rig replica they built in Louisiana (see sidebar). On the bridge, for example, there were real drilling rig instrument panels and computer screens, and Berg and some of the actors were tutored in the business and technology of deep water oil drilling.

On the bridge set for the Deepwater Horizon film, real oil rig instrument panels and control monitors were installed to give an authentic look.

In an interview on National Public Radio, Berg explained that he had the good fortune of attending a kind of “oil school” which was set up for him and others by some of the film’s producers. In that experience, Berg explained, “we were able to spend a lot of time with petroleum engineers and deepwater drilling experts,” who took them slowly and carefully enough through the process that they developed an appreciation and decent understanding of offshore drilling. Likewise, Gina Rodriguez, who plays Andrea Fleytas, the bridge officer who runs the Deepwater Horizon’s navigation controls, was sent to dynamic positioning school in Houston where she learned Fleytas’ duties aboard the rig. Rodriguez also spoke with Fleytas and studied audio tapes of her testimony during one of the government inquiries on the disaster.

|

Big Oil’s Turf As the film-makers sought to be as realistic as possible in making a film about an oil industry disaster in the Gulf of Mexico, they rightly came to the Gulf coast region and to Louisiana to do their filming. But as it turns out, according to director, Peter Berg, the oil industry, and BP in particular, wasn’t exactly excited about the prospect of a film on the Deepwater Horizon disaster. And in fact, according to Berg, BP went out of its way to make filming in Louisiana as difficult as possible. “…BP became a very effective disruptor and prevented us getting any access to any oil rigs. We couldn’t even fly by one. At one point we were in a helicopter on a tour of a rig called the Nautilus and were told if we got any closer we would be perceived to be a threat and they were going to defend themselves. The companies exert so much power because they are such financial engines in that part of the country – anyone who worked with BP basically said they couldn’t talk to us. We had consultants who would work with us for a day or two, but the third day they would call in sick and we would never hear from them again. We had contracts to film on the tenders that go back and forth to the rigs – then the day before, they would say we couldn’t. It became obvious that BP was doing a great job of intimidating most of the people down in that community. We understood it; it wasn’t a news flash. BP pays a lot of bills there, a lot of mortgages, sends a lot of kids to school, pays a lot of medical insurance. We realized our only option was to build our own rig – which we did… [more on this below] Berg also discovered that several of the people who were involved in the real-life incident had gag orders as a result of their settlement with BP, and “told us they could not speak with us.” And then there was the threat of BP legal action hanging over the production. Says Berg: “…The legal processes were something else.“It became obvious that BP was doing a great job of intimidating most of the people down in that community.” Lionsgate, our studio, had a team of independent lawyers who would review every word in the script… [Also]… in the final edits the lawyers were all over me; it was the first time in my career I have ever had to take mandatory edits from the studio….” The rig seen in the movie and used in filming was an 85 percent scale recreation of the actual Deepwater Horizon rig. But this “studio rig” was no small project – and in many ways, was an actual smaller rig using real materials. It was located in a rural area of Louisiana at an abandoned amusement park. The rig was constructed using 3.2 million pounds of steel, and was built inside of a giant, five-acre, two-and-a-half million gallon water tank. Peter Berg would say of this project: …[T]he set we built was about 85 feet in the air, was about size of about one and a half football fields, and underneath it was a 5-acre water tank that we could set on fire… [W]e could…blow up giant pieces of that set and blow oil and mud up in the air about 150 feet and land helicopters on it to do all kinds of things to try and provide the audience with an experience that…felt as authentic…as possible.”  An 85-percent scale recreation of the actual Deepwater Horizon drilling rig, using some 3.2 million pounds of steel, and set in a 5-acre water tank, had to be constructed in rural Louisiana due in part, to oil industry resistance to using an existing rig. “I’m pretty sure it’s the biggest practical set ever built, really ever, in the history of filmmaking. It’s certainly one of them,” Peter Berg said in a September 2015 Los Angeles Times story on the set. The main deck sat more than five stories in the air, and internally real materials were used from similar oil rigs on the bridge set and throughout other parts of the rig. “On the drill deck, all the mechanics above them, we built that for real,” explained production designer, Chris Seagers. “We thought we’d just rent that stuff, but then you realize each piece weighs 20, 30 tons. So we had to make it all…” The real Mike Williams acknowledged the set’s accuracies — “all the way down to the salt and pepper shakers in the galley.” In addition to meticulously recreating the rig, current and former oil workers and Coast Guard members were cast in smaller roles. In the end, the rig was set ablaze to recreate the explosions and inferno. The fact that this substitute rig had to be built from scratch, as opposed to using an existing or out-of-commission rig somewhere in the Gulf, meant that huge and unexpected costs were confronted, which certainly cut into the film’s profit, which was meager in the end. The film’s costs of $156 million, minus some production credits from the state of Louisiana, gave it net costs of about $120 million. Worldwide box office for the film was $122 million plus another $16 million in 2017 video sales. |

Reviews & Critics

On September 13, 2016, Deepwater Horizon had its world premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival, where, after its screening, it received a standing ovation. The film opened in theaters about a week later. Deepwater Horizon received generally positive reviews from critics and viewers. Audiences polled by CinemaScore, for example, gave the film an average grade of “A–”.

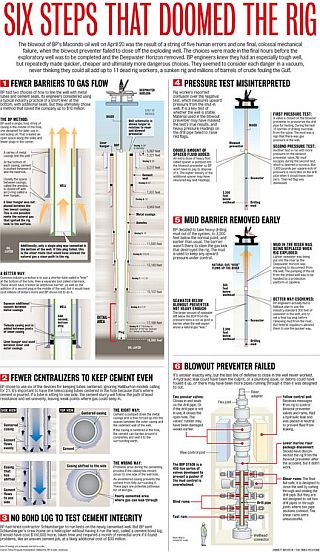

The Times-Picayune of New Orleans produced 'Six Steps That Doomed The Rig' in 2010. Click for larger version & details.

“The Deepwater Horizon movie is Hollywood’s take on a tragic and complex accident. It is not an accurate portrayal of the events that led to the accident, our people, or the character of our company. Morrell also said the film “ignores the conclusions reached by every official investigation: that the accident was the result of multiple errors made by a number of companies.”

Yes, true enough, other companies and the lack of government oversight share the blame. Yet the major errors at the Macondo well, and the setting of a culture of haste at the expense of safety, were those laid to BP.

(For those who might want more detail on the causes of the Deepwater Horizon blowout, click on the New Orleans Times-Picayune graphic at right for more detail and a somewhat larger version of “Six Steps That Doomed the Rig.”)

One of the film’s producers, Lorenzo di Bonaventura, explained that Deepwater Horizon sought to steer clear of simplistic depictions of corporate villainy, though it is clear that BP’s Donald Vidrine is wearing the back hat in this film, which is basically supported by the historical record (although perhaps compressed for the purpose of filmmaking).

“In those kinds of events, there is no black and white,” Di Bonaventura said in one interview about the film. “If you have an agenda, you’ll see this movie through your agenda. But it’s very important to us: It’s not an anti-oil movie. It’s not a pro-oil movie. It’s what happened that day.”

Most reviews of the film were positive. Benjamin Lee of The Guardian of London praised Berg’s direction as “admirably, uncharacteristically restrained…[He] stages the action horribly well, capturing the panic and gruesome mayhem without the film ever feeling exploitative. It’s spectacularly constructed, yet it doesn’t forget about the loss of life…”

Gina Rodriguez plays rig navigation expert, Andrea Fleytas, who has a near-death escape scene from the blazing rig.

Reviewers also found the performances of Wahlberg, Russell, Maklkovich, Rodriguez, and Hudson as bringing authenticity to the film.

“…Wahlberg proves a sturdy, sympathetic leader on a journey to an enormous floating hellscape,” wrote Ann Hornaday in her Washington Post review. Another thought Kurt Russell was especially good in his role, worthy of a best supporting actor consideration. And portions of Gina Rodriguez’s performance — especially those at near the end, showing human fear — added to the believability of how people react in life-threatening situations.

There was also one review from CatholicMom.com that found the film’s depictions of marriage, family life, faith – minor as they may appear – all to be pluses, from the Wahlberg-Hudson characters as a married couple in love, to Wahlberg’s sign-of-the-cross-moment and the surviving crew taking a knee to say the Our Father together.

True, there was some criticism of the film for straying too far from the actual events, or not getting things exactly right technically. Some felt there was too much technical detail, others not enough. Time magazine’s Justin Worland, who flagged some of the film’s shortcomings in his September 2016 review, nevertheless concluded: “…No movie is flawless and, as far as films based on true events go, Deepwater Horizon is pretty good. The average viewer will walk away from the movie with a new understanding of a complex disaster. And, as easy as it is to complain about the details, the film gets the gist of it right.”

Sample poster art for "Deepwater Horizon" film.

Less Marvel…

Whatever the technical, sequential, or composited shortcomings of this film may be, they are few and inconsequential as far as the main story line is concerned. On the whole, Deepwater Horizon is a genre of film that Hollywood should be lauded for making. Thank you, Lionsgate.

In fact, Hollywood should make more films like it. Lord knows there are lots of industrial calamities and pollution stories out there that need to be told, many with real human consequences and drama at their core.

History is full of such examples – from the coal mines, the steel mills, the chemical factories, and more. Hollywood needs to do much more in these arenas as a public service and for public education. Less Marvel, more realism.

For those interested in “Part II” of the Deepwater Horizon disaster – i.e., the actual oil spill and its aftermath — a bit of that history follows below, along with some of its media coverage. In addition, more than a dozen books on the spill, shown with cover art, are listed in “Sources” with Amazon.com links at the end of this article.

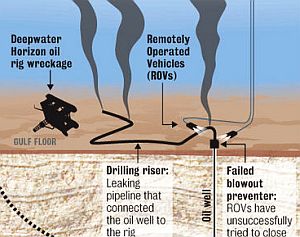

New Orleans Times-Picayune graphic showing Deepwater Horizon rig, disconnected riser pipe, and blowout preventer at the well head, all on the sea bed, 5,000 feet below Gulf surface. |

“SpillCam,” on the sea bottom at hemorrhaging well spewing thousands of bbls per day, became a split-screen 'star' during CNN and other TV broadcasts probing the spill. |

June 18, 2010. L. A. Times front-page photo & story on BP's Tony Hayward in Washington: “Head of BP Rejects Taking Blame.” |

June 17, 2010. Rep. Steve Scalise (R-LA) with photo of oil-covered pelican during hearings in Congress, as he admonished BP’s Tony Hayward to "keep this image in your mind". |

May 12, 2010. Front-page oil spill headlines from Florida’s ‘Pensacola News Journal’ featuring 'BP Holding Back' story & Senator Bill Nelson (D-FL) during Washington hearings. |

June 4, 2010. President Obama with Coast Guard Admiral Thad Allen, and speaking with press, at Deepwater Horizon oil spill response center in New Orleans, Louisiana. |

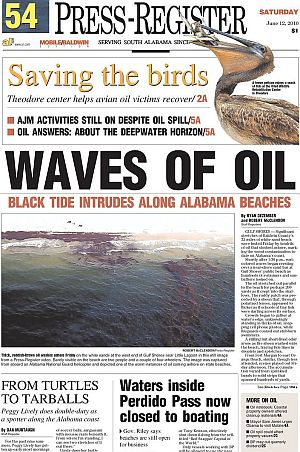

June 12, 2010. Portion of the front page of the Press-Register of south Alabama reporting on 'black tide' hitting the beaches. |

June 7, 2010. During Congressional hearing in Chalmette, LA, Rep. Bart Stupak (D-MI) holds up full-page BP newspaper ad to illustrate complaint about BP paying for advertising while Gulf Coast region faced financial need. |

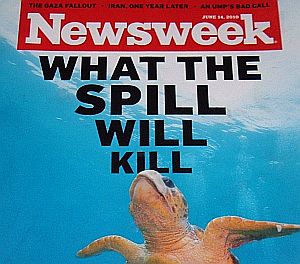

June 14, 2010. Portion of Newsweek cover, with featured story, "What The Spill Will Kill". |

June 12, 2010. Front page of The Mississippi Press showing oil on beaches of Petit Bois Island and reporting that latest spill projections look bad for wildlife and BP damages. |

June 14, 2010. Chemical & Engineering News cover story: 'Oil Spill Exposes Regulatory, Science Gaps'. |

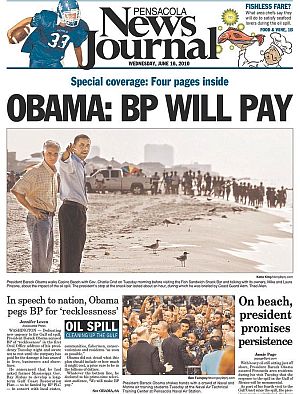

June 15, 2010. Pensacola, FL newspaper shows President Obama walking the beach with Governor Crist with headline, “BP Will Pay”, and story about Obama speech to nation. |

Signs of protest – like this one along a Grand Isle, LA highway in July 2010 – were spotted throughout the region, expressing anger of those whose lives and livelihoods were turned upside down by the spill, fishing restrictions, and oil drilling bans. |

Nov 2012. Wall Street Journal Europe on $4.5 billion in criminal fines for BP, with Clean Water Act fines yet to come. |

The Real Spill

After the Blowout…

Once the Deepwater Horizon drilling rig sank, the spill phase of the disaster began in earnest. It would last for more than 80 days — and the controversy would continue for years.

But unlike most other oil spills, this one was an underwater hemorrhage — deep underwater, more than a mile. Large oil slicks on the surface would take a while to form, and the oil wouldn’t reach coastal areas for some weeks. Still, national TV news coverage had begun with the rig explosion and would continue, along with extensive print coverage, throughout the spring and summer of 2010.

One prominent TV image became the real-time underwater camera – nicknamed “SpillCam” – that focused on the spewing crude from the blown out well at the bottom of the sea. The volume of oil escaping – originally estimated by BP to be about 1,000 barrels per day—would rise considerably over subsequent weeks as experts got a better fix on the volume, later figured by U.S. government officials and other experts to have been 60,000 barrels per day for much of the spill’s uncontrolled duration.

Magazine cover stories and front-page newspaper accounts lasted for months, including coverage of hearings in Washington and in the Gulf region, as BP executives, rig survivors, and government officials were summoned to answer questions from Congress, the U.S. Coast Guard, Dept. of Interior investigators, and others.

Throughout the ordeal, neither government nor industry fared very well in public opinion polls. Early on, there were some fairly dismissive comments by BP officials, either to press or made during hearings.

BP’s CEO at the time, Tony Hayward, in May 14th, 2010 comments to U.S. Secretary of the Interior, stated: “The Gulf of Mexico is a very big ocean. The amount of volume of oil and dispersant we are putting into it is tiny in relation to the total water volume.” A few days later, on May 18th, in other comments Hayward stated: “I think the environmental impact of this disaster is likely to be very, very modest….”

Somewhat later, as Hayward had suffered through a few inquiries and haranguing by the press, he was quoted saying: “…There’s no one who wants this thing over more than I do, I’d like my life back.” That comment was especially hurtful to the families of those killed in the rig explosion, also resented by many Gulf Coast residents whose lives and livelihoods had been turned upside down by the spill.

As plumes of oil formed on the sea surface, strategies were deployed to spray the spill with chemical dispersant to break up, congeal, and sink it. There were also “controlled burns” of corralled portions of the oil slick at sea. Both methods were billed as ways to keep the spill from moving inland, to protect wetlands and beaches. Neither of these strategies were especially popular, and the chemical dispersant, Corexit, was suspect as a toxic problem itself.

At the White House, initially, there had been no verification of a major spill problem. Although briefed by the Coast Guard on the search and rescue operations following the rig explosion, there appeared to be little concern in the Obama Administration about a spill — at least at first. Once the rig sank, there was heightened concern and more briefings, though the requisite federal agencies were assumed to be handling the situation.

Only weeks earlier President Obama had proposed expanding the government’s offshore oil leasing program. And during remarks on April 2, 2010, Obama was quoted as saying: “It turns out, by the way, that oil rigs today generally don’t cause spills. They are technologically very advanced. Even during [hurricane] Katrina, the spills didn’t come from the oil rigs. They came from the refineries on shore.” But soon, the Administration would discover that advanced offshore technologies had their shortcomings.

Once it was clear there was a major spill, the president sent his top energy and environmental officials to the Gulf region to assess the problem. The Coast Guard was already working with BP. On April 29, the president said he would use all in his power to contain the spill, including bringing in the U.S. military if necessary. The following day, the White House ordered that no new offshore drilling would be permitted until the cause of Deepwater Horizon disaster was determined.

Meanwhile, at the main event – i.e., trying to stop the hemorrhaging well – BP struggled with its technology and various jerry-rigged methods.

When the drilling rig sank (see diagram above right), the long riser pipe between it and the well 5,000 feet below broke off at the rig end, though staying connected to the top of the giant blowout preventer atop the well on the sea bed below. It would later be learned that there were leaks along the riser pipe, at the blowout preventer, and at the well head.

First, BP tried, via deep-sea robot, to manually turn on the blowout preventer, but that didn’t work. BP had also begun, by May 2nd, drilling relief wells, one designed to intersect the Macondo well so it could be plugged with cement. But that well wouldn’t be complete until August, nearly two months away.

Then BP began fashioning a giant, 125-ton containment dome on land, later brought to the site on a separate vessel. This massive structure was lowered over the spewing well on May 7th with the hope that it would trap and siphon off some of the escaping oil, sent to surface vessels. But deep-sea ice hydrates foiled that attempt.

Back in Washington, meanwhile, three executives from BP, Transocean and Halliburton testified on May 11th before a U.S. Senate committee, each blaming one or both of the other companies for the incident.

Several days later, on May 15th, scientists reported huge underwater plumes of oil – one six miles wide and 22 miles long. These underwater “clouds of oil” consisted of oil beads believed to be the result of chemical dispersants used on the spill. The underwater plumes were moving with the current toward the coastline.

Back at the well, on May 16th, BP inserted a narrow tube into the riser pipe, capturing a small portion of the escaping oil and pumping it to a surface ship. But the well was still releasing tens of thousands of barrels per day into the Gulf.

By May 19th, the oil was reaching Louisiana wetlands at the mouth of the Mississippi River. “This wasn’t tarballs, This wasn’t sheen,” reported Louisiana governor Bobby Jindal. “This is heavy oil in our wetlands.” Oil had also hit the Chandeleur Islands earlier in May, barrier islands that comprise an eastern boundary for Louisiana and include part of the Breton National Wildlife Refuge.

By late May, NOAA — the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration — had closed nearly 20 percent of the Gulf of Mexico to fishing. The toll on wildlife and natural resources mounted day by day, and throughout the ordeal, there were heroic efforts to save and treat oiled wildlife. On June 28th, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission began digging up turtle egg nest on Florida’s Panhandle Gulf Coast and moving them to the state’s Atlantic coast – thousands to be moved this way by November 2010. Reporting by the Los Angeles Times on wildlife losses found that by August 2010, some 516 dead sea turtles had been collected and more than 3,900 dead birds. The Audubon Society would later report that more than one million birds were killed.

On May 22nd, President Obama ordered the creation of a bi-partisan national commission on the spill to report on the root causes of the disaster and options for improved safety and environmental protection. Five days later, on May 27th, he announced a six month moratorium on new deep water drilling.

Obama would make several trips to the Gulf region during the duration of the BP spill, meeting variously with Coast Guard officials, state governors, fishermen, local residents, and walking beaches. His first visit came on May 2nd, 2010, when he traveled to Venice, Louisiana.

Back in Washington, on June 1st, Attorney General, Eric Holder, announced that the Justice Department would begin a criminal and civil investigation of the oil spill.

Meanwhile, attempts to control the hemorrhaging well continued with more of BP’s “technological-trial-and-error.” On May 26th, BP tried a maneuver it called “top kill,” using a 30,000 bbls of mud-like liquid to staunch the flow. Along with that was “junk shot,” using golf balls and shredded tires in an attempt to clog up the blowout preventer to stop the flow. Neither worked. By May 27th the oil was reported to be leaking at a rate of 19,000 bbls per day, a rate later found to be low.

Public opinion polls were extremely critical of BP’s response. Across the U.S. at one point, thousands participated in protests at BP gas stations and other locations, actions which reduced BP sales at some stations by 10-to-40 percent. BP’s stock suffered and its reputation sank to all time lows. By June 1st, BP’s stock value had fallen some 40 percent, a reduction of nearly $75 billion in shareholder value.

On June 3, BP began an advertising campaign in the U.S. aimed at boosting public opinion. Tony Hayward was featured in one of the first TV spots, and also on the company’s Facebook page offering a mea culpa for his earlier “I-want-my-life-back” remark. Here’s Hayward in one of the June 3rd TV ads:

“The Gulf spill is a tragedy that never should have happened.

” … BP has taken full responsibility for cleaning up the spill in the Gulf… We’ve helped organize the largest environmental response in this country’s history… Where oil reaches the shore, thousands of people are ready to clean it up. We will honor all legitimate claims. And our cleanup efforts will not come at any cost to taxpayers.

“To those affected and your families, I am deeply sorry. The Gulf is home for thousands of BP’s employees and we all feel the impact. To all the volunteers and for the strong support of the government, thank you. We know it is our responsibility to keep you informed. And do everything we can so this never happens again. We will get this done. We will make this right.”

The same message appeared in major newspaper ads. BP in fact, more than tripled its advertising budget in the U.S. in the three months after the explosion to combat negative publicity and rising public anger. Between April and early July 2010 by one estimate, BP spent $93 million on advertising.

BP’s campaign also included local newspaper ads, run in 126 markets in 17 states, including the those directly impacted by the oil spill. Rep. Kathy Castor (D-FL), one of those critical of BP’s campaign, said at one point:

“BP’s extensive advertising campaign that is solely focused on polishing its corporate image in the wake of the Deepwater Horizon blowout disaster is making people angry… As small businesses, fishermen, and mom and pop motels, hotels and restaurants struggle to make ends meet, they are bombarded by BP’s corporate marketing largesse day after day.”

In one interesting move to capture the informational high ground on public queries, BP purchased Google and other search engine page-one positioning (shown as top-of-page sponsored content) for search terms such as “oil spill.”

Further work at the well continued as BP moved with underwater robots to shear off the riser pipe from the gushing well. This was part of a plan to install a containment cap, which was successful, as some siphoning off of escaping oil began. Still, by June 10th, the government was then estimating that 25,000-to-30,000 bbls of oil per day were flowing into the Gulf.

On June 15th BP officials met with President Obama at the White House. The following day, BP announced it was setting up a $20 billion escrow fund for damages and claims and also agreed to set aside $100 million to pay lost wages to oil workers left unemployed by the disaster.

On July 12th, BP installed a “capping stack” to provide a tighter seal on the well – this until the relief wells were completed. Three days later BP reported that the hemorrhage had stopped. However, there was continuing question that all the leakage had stopped.

On August 4th, BP reported that its ‘static kill’ attempt to stop the oil leak by pumping mud into the well had been successful, though more mud may still have to be pumped into the well. The following day, on August 5th, BP pumped cement into the blown-out well, asserting the leak was permanently sealed. The U.S. government, however, wouldn’t declare the well “effectively dead” until September 19th, 2010, some five months after the blow-out.

Once the well was capped, there was still plenty of drama ahead and years of settling up – cleaning up the mess, investigating the accident, adjudicating blame, assessing damages, parsing claims, and making reparation. While the spill was in progress, a series of inquiries, hearings, and investigations had already begun – one joint investigation by the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Regulation and Enforcement and the U.S. Coast Guard. Various committees in the U.S. Congress also conducted hearings, some held in the Gulf region. By early July 2010 at least 19 congressional committees — 11 House and eight Senate — had held hearings on the rig failure and/or the oil spill.

Then came a variety of reports – a few from the companies involved, as well as more weighty tomes from government agencies. Each of the reports, in one way or another, implicated one or more of principals – BP, Transocean, and Halliburton. These reports also enumerated a series of mistakes, bad calls, and failed technology in one way or another, some shifting blame more this way or that, while others tried to remain neutral.

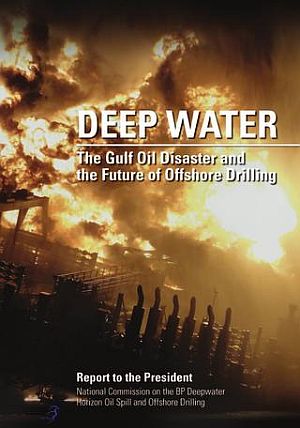

Notable among the reports was that of the Obama-appointed, bi-partisan national commission on the Deepwater Horizon, released in early January 2011. This 390-page report to the President – titled Deepwater: The Gulf Oil Disaster and The Future of Offshore Drilling – concluded the blowout was “avoidable” and resulted from “clear mistakes” made by BP, Halliburton and Transocean. But theses mistakes, said the commission “reveal such systemic failures in risk management that they place in doubt the safety culture of the entire industry.”

At one of the Commission’s earlier briefings it was also stated there had been “a rush to completion” on the Macondo well and, “there was not a culture of safety on that rig.”

One example of that failing came when rig operators were doing a “negative pressure test” to check the integrity of the cement job on the well to prevent gas from leaking. Co-chairman Bill Reilly explained that the operators didn’t like a reading they were getting from the drill pipe test, so they did a second test on another piece of equipment, which came out better.

“Inexplicably,” said Reilly, “a decision was made to take the reassuring test result without trying to figure out why it was inconsistent with the information coming up the drill pipe.” The report blames the operators for failing to communicate the inconsistent results to their onshore operations and states that if they had, the blowout may not have occurred.

In another example, before the accident, Halliburton found that the cement slurry it planned to use was not stable, but Halliburton did little to warn BP.

The report also singled out “government officials who, relying too much on industry’s assertions of the safety of their operations, failed to create and apply a program of regulatory oversight that would have properly minimized the risk of deepwater drilling.”

Commission co-chairman Bob Graham, former US. Senator (D-FL), said at the report’s release: “I’m sad to say that part of the answer is the fact that our government let it happen… Our regulators were consistently outmatched. The Department of Interior lacked the in-house expertise to effectively enforce regulation.”

Meanwhile, in London in November 2011, Tony Hayward, by then no longer BP’s CEO (resigned July 27, 2010), made some fairly stunning revelations about the disaster to BBC television and other news outlets – namely, that “BP’s contingency plans were inadequate,” and “we were making it up day to day.” Hayward added, however, that BP was actually doing “some extraordinary engineering” under the circumstances – “tasks completed in days that would normally take months, numerous major innovations with lasting benefits.” But when these efforts were “played out in the full glare of the media,” he said, “it looked like fumbling and incompetence.”

“While we were able to mount a massive response to contain and disperse the oil on the surface,” Hayward said, “we did not have the equipment to contain and disperse on the seabed. In fact the equipment had never been designed or built. It simply did not exist.” And it wasn’t just BP that was unprepared for a deep water disaster. “The whole industry,” he said, “had been lulled into a sense of false security after 20 years of drilling in deep water without a serious accident…” For BP, he said, the Deepwater Horizon event “was the ultimate low-probability, high-impact event – a black swan to borrow a term used in the financial crisis.”

“Embarrassingly we found ourselves having to improvise on prime-time TV…”

In November 2012, BP and the U.S. Department of Justice settled federal criminal charges with BP pleading guilty to 11 counts of manslaughter, two misdemeanors, and a felony count of lying to Congress. As of February 2013, criminal and civil settlements and payments to a trust fund had cost the company $42.2 billion. In September 2014, a U.S. District Court judge ruled that BP was primarily responsible for the oil spill because of its gross negligence and reckless conduct. In July 2015, BP agreed to pay $18.7 billion in fines, the largest corporate settlement in U.S. history.

All told, BP is on the hook for something north of $60 billion for all Deepwater Horizon related charges, portions of which were being paid by the company over time in smaller annual installments continuing through 2018 and beyond.

Still, today, BP survives and remains one the world’s largest corporations, continuing to drill for oil around the world. In fact, by late April 2012, it was starting work on three new Gulf of Mexico oil rigs – then making a total of eight new BP drilling sites in the Gulf of Mexico, more than it operated before the Deepwater Horizon disaster.

The Obama Administration for its part, did move to reorganize the U.S. Department of the Interior’s Minerals Management Service (MMS), which was found to have exercised poor industry oversight and had internal conflicts of interests. In October 2011, MMS was dissolved and divided into three new agencies: the Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement, for regulation; the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management for leasing; and the Office of Natural Resources Revenue for revenue collection.

The disaster’s economic impacts on the Gulf region were considerable: the coastal tourism industry lost about $22.7 billion, and the area’s commercial fishing industry, $247 million. BP faced more than 390,000 claims from fishermen, seafood producers, and tourism providers, and most of these were paid, or will be paid, when determined to be valid. Wildlife losses, ecological and natural resources damage have also been significant, with ongoing studies and assessments still being made.

Encyclopedia Britannica map of the Gulf of Mexico and region showing former location of the Deepwater Horizon drilling rig and the extent of the oil spill, impacted shoreline areas, and the spill’s relation to Gulf currents.

The lessons of the 2010 Deepwater Horizon disaster loom large over the world’s offshore oil regions – whether the Gulf of Mexico, the North Sea, Southeast Asia, Eastern Africa, or the Australian Bight. As drillers push into more remote frontier regions with harsh conditions, and move into deeper and deeper waters with attendant geologic pressures, risks and unknowns will rise, and the world will be but one mistake, one unfortunate decision, or one technological glitch away from the next fiasco. Greenland, taking a cue from the Deepwater Horizon disaster, announced it November 2010 that it will require a $2 billion “bond” up front from oil companies who want to drill in its Arctic waters.

Added to the possibility of future Deepwater Horizon-type events, and perhaps more problematic, is the continuing “routine” assault of offshore oil spills, pipeline breaks, and drilling rig mishaps that rarely make the evening news. And of those recorded in recent years since the Deepwater Horizon by Interior’s new Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE), there is not much to cheer about. Here are some totals of reported incidents for the 2011-2017 period, occurring across offshore leases in the federal outer continental shelf region (of which the Gulf of Mexico is the largest), based on BSEE categories: 74 collisions, 377 evacuations (or musters for evacuation), 760 fires and explosions, 119 gas releases, 26 loss-of-well-control incidents (which can be a precursor to a blowout), 129 spills (oil, drilling mud and/or chemicals), more than 1,400 injuries, and 13 fatalities. These numbers do not include incidents in state offshore waters or other inland waters. Nor do they include “unreported” incidents. In the Gulf of Mexico, there are thousands of rigs operating.

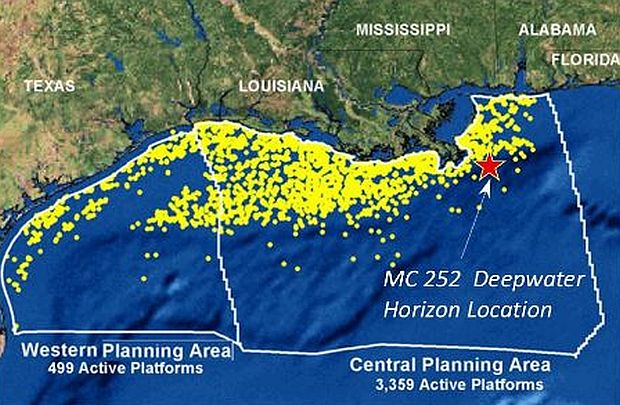

Map of some 3,858 oil and gas platforms in the Gulf of Mexico as of 2006, also showing the former location of the Deepwater Horizon rig. The yellow dots used to note platform locations are not to scale and exaggerate the density of platforms. NOAA 2012.

Another concern in the Gulf of Mexico, according to an investigation by Associated Press (AP), are more than 27,000 abandoned oil wells found there from a host of companies, including BP. AP has described the area as “an environmental minefield that has been ignored for decades”. Some of these wells date back to the 1940s, and state officials estimate that thousands of them are badly sealed. There are also 43,000 miles of underwater pipeline and pumping stations in the Gulf.

In any case, the likelihood of more offshore incidents occurring in U.S. waters in the years ahead has increased significantly with recent actions by the Trump Administration. In December 2010, the Obama Administration had backed away from plans to expand offshore oil and gas development, designating the waters of the Atlantic seaboard and the eastern Gulf of Mexico off-limits for at least another seven years. The Obama Administration also strengthened offshore regulations in the aftermath of the Deepwater Horizon disaster. However, the Trump Administration has now reversed all of that, and has sought to expand offshore oil and gas development in all U.S. waters. Coastal communities and environmental organizations throughout the nation are girding for the battles ahead. Stay tuned.

Additional stories on the environment and the oil industry at this website can be found at the “Environmental History” topics page. Thanks for visiting — and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research and writing at this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

____________________________________

Date Posted: 14 July 2018

Last Update: 16 June 2021

Comments to: jdoyle@pophistorydig.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Deepwater Horizon: Film & Spill: 2010-2016,”

PopHistoryDig.com, July 14, 2018.

____________________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

Deepwater Horizon, Official Movie Site.

“Deepwater Horizon(2016),” Plot Summaries & Synopsis, IMDB.com.

“Deepwater Horizon (film),” LionsGatePubli-city .com.

“Deepwater Horizon Production Notes,” Lions GatePublicity.com.

“Deepwater Horizon (film),” Wikipedia,org.

David Barstow, David Rohde, and Stephanie Saul, “Deepwater Horizon’s Final Hours,” New York Times, December 26, 2010, p. 1.

Testimony of Mike Williams, “Deepwater Horizon Explosion & Oil Spill,” Hearings for the Joint investigation of the U. S. Coast Guard (USCG) and the U.S. Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Ocean, Energy Management, Regulation, and Enforcement, Kennar, Louisiana, July 23, 2010 (video), via C-SPANN.org.

“Extended Interview: Deepwater Horizon Survivor” (Mike Williams), CBS News(60 Minutes), YouTube.com, September 20, 2010 (shorter program aired on May 16, 2010).

Michael Ordona, “How ‘Deepwater Horizon’ Director Peter Berg and Crew Created What Could Be the Biggest Set Ever Built,” Los Angeles Times, September 1, 2016.

Andrea Mandell, “Fame Didn’t Help Mark Wahlberg Make ‘Deepwater’,” USA Today, September 14, 2016

Mike Ryan, “‘Deepwater Horizon’ Just Debuted At TIFF And It Will, And Should, Make You Angry,” Uproxx Movie Reviews, September 13, 2016.

Josh Rottenberg, “Telling the True Story of the Heroes Behind ‘Deepwater Horizon,’ Without Using ‘Stolen Valor’,” Los Angeles Times, September 22, 2016.

Lorne Manly, “Risky Business: Hollywood Bets Big on ‘Deepwater Horizon’,” New York Times, September 22, 2016.

Loren Steffy, “Truth and Fiction on the Horizon; the Worst Offshore Oil Disaster in U.S. History Is Getting the Hollywood Treatment in ‘Deepwater Horizon,’ out Today,” Texas Monthly, September 29, 2016.

A. O. Scott, Review, “In ‘Deepwater Horizon,’ Oil, Fire and Greed,” New York Times, September 29, 2016.

Steve Persall, “Mark Wahlberg Talks Real Life Heroics on Set of ‘Deepwater Horizon’,” Tampa Bay Times, September 27, 2016.

Joel Achenbach, “‘Deepwater Horizon’ Movie Gets the Facts Mostly Right, But Simplifies the Blame,” Washington Post, September 29, 2016.

Matt Kamen, “The True Story Behind the Horror of Mark Wahlberg’s Deepwater Horizon; this Weekend’s Big Action Movie Is Deepwater Horizon – But the Real World Impact of the Disaster It’s Based on Is Still Being Felt,” Wired, September 29, 2016.

Justin Worland, “The True Story Behind the ‘Deepwater Horizon’ Movie,” Time, September 30, 2016.

Lindsey Bahr, Associated Press, “Compelling ‘Deepwater Horizon’ Brings BP Oil Rig Disaster to Life on Screen,” September 30, 2016.

Reuters Staff, “BP Decries Deepwater Horizon Film as Inaccurate,” September 30, 2016.

Andrew Ward and Ed Crooks, “BP Gives Deepwater Horizon Disaster Film a Scathing Review; Account of Oil Spill Highlights Hollywood’s Ability to Influence Corporate Reputations,” Financial Times, September 30, 2016.

James B. Meigs, “Blame BP for Deepwater Horizon. But Direct Your Outrage to the Actual Mistake. It Was Years of Cutting Corners, Not One Careless Mistake, That Caused the Explosion,” Slate.com, September 30, 2016.

“Deepwater Horizon (film),” HistoryVsHolly- wood.com.

Dave Davies (substitute host),National Public Radio /Fresh Air, “’Deepwater Horizon’ Director On The BP Oil Spill And The ‘Addictive Dance’ For Fuel” (Interview with Peter Berg), NPR.org, September 26, 2016.

Rebecca Onion, “’Deepwater Horizon’ an Emotional Spectacle But Sidesteps Disaster’s Impact,” Newsweek.com, October 1, 2016.

Lisa Hendey, “Deepwater Horizon: Love, Heroism & Faith Amidst the Flames,” CatholicMom.com, October 1, 2016.

Peter Berg, “The ‘Well From Hell’ – My Fight with BP to Film Deepwater Horizon,” The Guardian, October 4, 2016.

David Hunn and Ryan Maye Handy, “Deepwater Horizon Survivors Give New Film Mixed Reviews; BP Bashes Disaster Flick, Calling it Inaccurate,” Houston Chronicle, October 4, 2016.

Bill Newcott, “ ‘Deepwater Horizon’ Explodes With Action; Kurt Russell Saves the Day as a Skipper Who Knows the Drill,” AARP.org, September 29, 2016.

Emma Krupp, “Interview: From ‘Jane the Virgin’ to ‘Deepwater Horizon,’ Gina Rodriguez is about empathy,” Chicago Tribune, September 29, 2016.

Deepwater Horizon Blowout & Spill

_______________________________

Douglas A. Blackmon, Vanessa O’Connell, Alexandra Berzon, and Ana Campoy, “‘There Was ‘Nobody in Charge’; After the Blast, Horizon Was Hobbled by a Complex Chain of Command; A 23-Year-Old Steps in to Radio a Mayday,” Wall Street Journal, updated, May 27, 2010.

The White House, Office of the Press Secretary, “Remarks by the President on Oil Spill” (Venice, Louisiana), May 2, 2010, 3:25 P.M. CDT.

Evan Thomas, “Plugging Oil Leak Won’t Stop Political Fallout,” Newsweek, May 28, 2010.

Richard Pallardy, “Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill of 2010; Environmental Disaster, Gulf of Mexico,” Britannica.com.

Debbie Elliott and Scott Horsley, “How An Oil Spill Spread Into A National Crisis,” Morning Edition / National Public Radio, May 5, 2010.

“Special Series / Gulf Oil Spill: Containment And Clean Up,” NPR.org, 2010-2011.

Jeff Johnson and Michael Torrice, (Cover Story), “BP’s Ever-Growing Oil Spill,” Chemical & Engineering News, June 14, 2010.

“Deepwater Horizon Oil spill,” Wikipedia.org.

“Chronology of a Catastrophe,” Chemical & Engineering News, June 14, 2010.

“100 Days of the BP Spill: A Timeline,” Time.com.

“Timeline of the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill,” Wikipedia.org.

Sean Smith, Graham Parrish and Steven Bernard, “Interactive Timeline: BP Oil Spill Disaster,”

Financial Times, August 2010.

Heidi Avery, “The Ongoing Administration-Wide Response to the Deepwater BP Oil Spill,”

The White House, May 5, 2010 (April 20-through-May 24, 2010 chronology).

Emily Cohen, “BP Buys ‘Oil’ Search Terms to Redirect Users to Official Company Website,”

ABC News, June 5, 2010.

“The Role of BP in the Deepwater Horizon Explosion and Oil Spill,” Hearing Before the Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations, Committee on Energy and Commerce, U.S. House of Representatives, 111th Congress, Second Session, June 17, 2010, Serial No. 111–137

Richard Simon and Scott Kraft, “Head of BP Rejects Taking Blame; Facing Lawmakers, He Apologizes and Promises Action, While Declining to Answer Many Questions,” Los Angeles Times, June 18, 2010.

Daily Mail Foreign Service, “Sliced and Diced on Capitol Hill: BP Boss Treated Like Public Enemy No. 1 by American Politicians,” Daily Mail (London), June 18, 2010.

Bruce Alpert, “Gulf of Mexico Oil Spill Debate in Congress Often Short on First-hand Insight,” Times-Picayune NOLA.com, July 2, 2010.

Jamie Friedland, “Deepwater Drilling Moratorium Version 2.0,” Political Climate, July 14, 2010.

Russell Gold, “Rig’s Final Hours Probed; Spill Investigators Focus on 20 ‘Anomalies’ Aboard Doomed Deepwater Horizon,” Wall Street Journal, updated, July 18, 2010.

“Assessing Natural Resource Damages Resulting From the BP Deepwater Horizon Disaster,” Hearing Before the Subcommittee on Water and Wildlife, Committee on Environment and Public Works, United States Senate, 111th Congress, 2nd Session, July 27, 2010.

Bruce Alpert, “BP’s $93 Million Spent on Advertising after Gulf Oil Spill Is Questioned,” Times-Picayune, September 1, 2010.

Richard Adams and Adam Gabbatt, “BP Oil Spill Report – as it Happened; BP Released its Report into the Oil Spill Which Followed the Deepwater Horizon Explosion in the Gulf of Mexico,” The Guardian, September 8, 2010.

Justin Mullins, “The Eight Failures That Caused the Gulf Oil Spill,” New Scientist, September, 8, 2010.

James C. Mckinley, Jr., “Documents Fill In Gaps in Narrative on Oil Rig Blast,” New York Times, September 7, 2010.

“The Spill,” Frontline & ProPublica, PBS.org, November 2010.

“Tony Hayward Says BP Was ‘Not Prepared’ for the Gulf Oil Spill,” BBC.com, November 9, 2010.

Terry Macalister, “Tony Hayward: Public Saw Us as ‘Fumbling and Incompetent’; Ex-BP Boss Says When Oil Spill Hit, BP Was Forced to Make up Disaster Response as it Went Along,” The Guardian, November 10, 2010.