Colossal earth-moving machines became symbols in the 1960s-1970s environmental battles over surface coal mining, also known as “strip mining.” These machines – some capable of scooping two-to-three Greyhound bus-size equivalents of earth with each bite – laid waste to tens of thousands of acres as they uncovered near-surface coal to feed electric power plants. In 1972-73, a trio of these machines, then chewing through southeastern Ohio, became involved in a controversial proposal: to cross, and temporarily shut down, a major interstate highway to get to the coal on the other side. The event became a symbolic and actual “line-in-the-sand” confrontation between those opposed to strip mining and those who saw it as vital for energy, jobs, and local economies.

The February 1973 issue of Smithsonian magazine ran a dramatic shot of “The GEM of Egypt” in operation in the Egypt Valley of Ohio, just north of I-70, as the magazine featured a story on “the need for energy vs. strip mining.” Note size of the shovel’s bucket relative to the vehicles on the road below. Photo, Arthur Sirdofsky.

There were three of the giant machines at issue: The Tiger, The Mountaineer, and The GEM of Egypt. All three were then in the service of the Hanna Coal Company, which by 1970, had been strip mining in Ohio for decades and was then a division of the much larger Pittsburgh Consolidation Coal Company, later known as “Consol,” itself then owned by Continental Oil. More on Hanna/Consol and the big machines in a moment, first some background on Ohio’s coal.

Ohio’s Coal

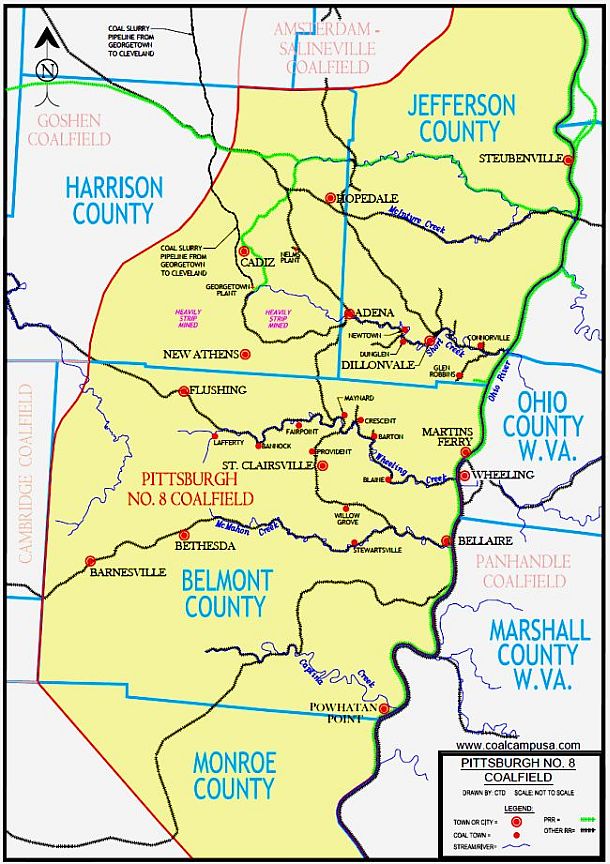

Various coalfields in the tri-state OH-PA-WV area are shown in color, overlaying county boundaries – a region where coal has been mined for decades in the Appalachian Coal Basin.

Coal has been mined in Ohio since the early 1800s, initially with crude mining techniques working surface outcroppings, to more sophisticated mechanized technologies that evolved following WWI and WWII. Most of the mining in Ohio through the 1930s was in deep mines or shaft mines that bore into mountainsides. Surface mining existed as well, but it wasn’t until the big shovels came on in the 1940s and 1950s that strip mining began to take a larger portion of the state’s annual coal production.

Generally it is economic to strip mine when there is a 20:1 ratio of overburden-to-coal seam, meaning, for example that a three-foot coal seam can be surface mined economically when the overburden is up to 60 feet. However, at some surface mines in Ohio, highwalls of up to 200 feet high remain where five-foot-coal seams have been extracted. And in these cases, the size and power of the giant shovels and draglines used in those areas made that level of extraction possible.

The Big Shovels

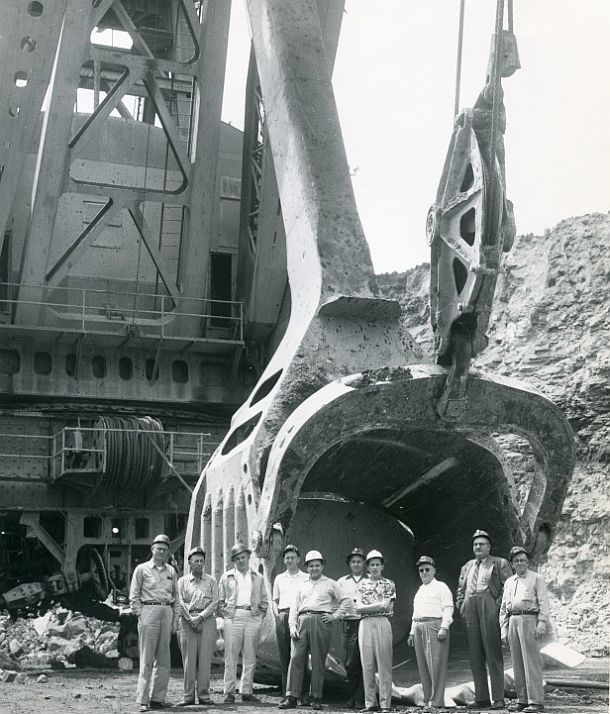

The smallest of Hanna Coal Company’s earth movers involved in the I-70 controversy, The Tiger, was among the company’s first big shovels, built in the early 1940s. But even for that “small” shovel, mining historians noted that it took about 63 trainloads to ship its parts from Marion, Ohio to Hanna’s Georgetown coal complex south of Cadiz, Ohio in Harrison County, where it was assembled. The shipping and assembly of the shovel began in 1943, and by the following year, The Tiger was ready to begin digging. At the time, it was considered to be the world’s largest shovel, used to help mine coal for the steel mills during WWII. The photo below shows a portion of The Tiger in 1957 near Cadiz, Ohio.

The Tiger shown during a 1950s field tour. This shovel first began its work in Harrison County, Ohio in 1944, moving on to other coal fields in Ohio through the 1970s.

The Hanna Coal Company, meanwhile, was quite an Ohio industrial power, evolved initially from Rhodes & Co., a firm in the 1840s that mined coal in Ohio’s Mahoning Valley area. Hanna expanded into iron ore mining in the Lake Superior region in the mid-1860s, establishing roots in the steel industry. Some years later, after considerable growth over the decades, and various business transactions, stock trades, mergers, and restructurings, including the sale of its iron and steel interests, Hanna, by 1945-46, became part of what was then called the Pittsburgh Consolidation Coal Company (Pitt-Consol). In this deal, Hanna brought to Consol its eastern Ohio coal properties, which then accounted for about 20 percent of Ohio’s production. A few years later, Pitt-Consol acquired more Hanna coal lands in Ohio’s Harrison, Belmont and Jefferson counties. But Hanna, as a Consolidation company, continued to operate in these areas under its name.

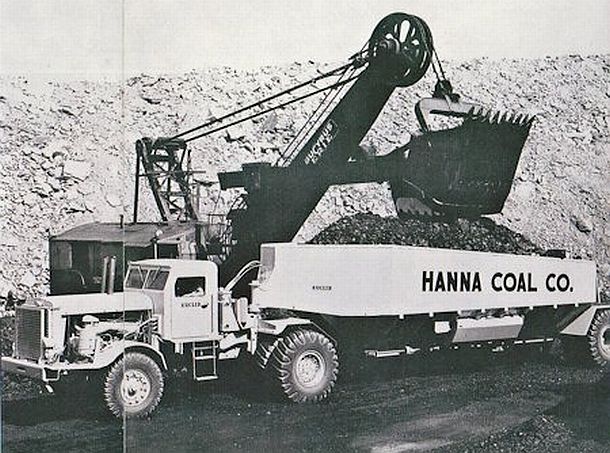

Undated photo (probably circa 1950s) of a smaller Bucyrus-Erie electric shovel loading a 55-ton Euclid truck at one of Hanna's coal mines. The loaded coal would then go to Hanna’s Georgetown prep plant for cleaning and shipping.

Hanna became one of the major players in the Eastern and Southeastern Ohio coalfields for many years. By the 1950s at Duncanwood, Ohio, near Cadiz in Harrison County, Hanna had a complex of offices and shop buildings, and also a major coal processing center at its giant Georgetown complex of coal mines, tipples, and railroads. The company’s coal cleaning operations there, which opened in 1951, was then one of the largest preparation plants in the world, and could process 1,275 tons/hour – which was quite formidable in the 1950’s. Hanna was also one of the first to use a coal slurry pipeline to transport coal over a long distance. In 1956 the company built a 10-inch, 108-mile-long pipeline that linked the Hanna’s Georgetown prep plant near Cadiz with the Cleveland Electric Company’s Eastlake Generating Station in Cleveland. Crushed coal was mixed with water at a Hanna plant and the slurry mixture then pumped through the line to Cleveland. Between 1957 and 1963, this pipeline supplied about six million tons of coal to Cleveland Electric.

Headlines from July 1966 when Hanna made a big investment in a nearby West Virginia deep mine.

At its deep mine locations, especially in earlier years, Hanna built company housing for its miners, such as those built for workers at the Dunglen mine at Newtown, Ohio. It also operated company stores – those invoked generally by the Tennessee Ernie Ford song, “Sixteen Tons.” Two of Hanna’s stores were those named Dillonvale and Lafferty, and another one was located at Willow Grove, Ohio. First Lady, Eleanor Roosevelt, had visited Hanna’s Willow Grove deep mine in April 1935. Below is an enlarged map of several Ohio counties where Hanna Coal Company mines and machines exploited the Pittsburgh No. 8 Coalfield for many years.

Map showing the Pittsburgh No. 8 Coalfield, running beneath Southeastern Ohio counties where Hanna Coal Co and others operated strip and deep mines and other facilities for decades. Source: CoalCampUSA.com

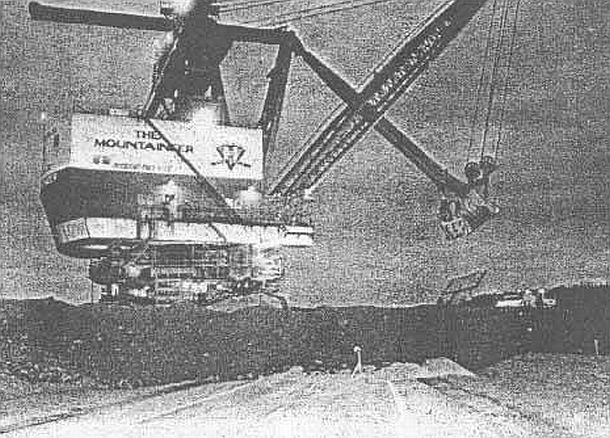

Hanna’s Ohio strip mining, meanwhile, was aided through the 1950s by another of the big machines, The Mountaineer, built by the Marion Co. The Mountaineer was among the first of the big “super strippers.” This colossus was also assembled in pieces, near Cadiz, Ohio, a build that began in June 1955. The big shovel didn’t start digging until January 30, 1956. The Mountaineer had a 65-cubic-yard dipper, stood 16 stories tall, with a 150 foot tall boom. Its shovel could hold a 100-ton payload. The Mountaineer was the first shovel to have a built-in elevator for the crew to reach the operating controls, in this case, located in dual cabs at the front of the machine, one on each side.

The Mountaineer shovel, from a Life magazine photo in the 1950s, shows the colossal size of this earth mover relative to nearby vehicles, locomotive, and group of workmen.

The GEM of Egypt (“GEM,” an acronym for “Giant Earth Mover” or “Giant Excavating Machine”), the largest of the three shovels in Hanna’s employ, went into service in January 1967 (There was also a fourth giant shovel that Hanna used, The Silver Spade, sometimes called the “sister” to The Gem of Egypt, also used in Ohio, but not involved in the I-70 crossing. The Spade in 1965 had worked at Hanna’s Georgetown Mine near Cadiz, among other places, active through 2008). The Gem of Egypt was 20 stories tall and weighed 7,000 tons. It had a 170-foot boom and a 130 cubic yard bucket. It first went to work at the opening of the Egypt Valley mine in January 1967.

Photo of The Gem of Egypt shovel, believed to be around the time it began operating in the Egypt Valley of Ohio in the late 1960s. Note the size of the machine relative to the people standing near its shovel and around its base.

Hanna invited the public to attend the grand opening of the Egypt Valley Mine in late January 1967. An estimated 25,000 people traveled to the site, many from Ohio cities such as Cleveland, Akron, and Canton, as well as those from neighboring states. The centerpiece of the tour was the colossal GEM of Egypt, which towered over the visitor’s cars parked near it that day. The GEM, in fact, was capable of holding the equivalent of at least two Greyhound buses in its bucket. The giant earth mover was slated to operate in Hanna’s 96,000-acre Egypt Valley surface mine in Belmont County. Production there was expected to average 20,000 tons a day until the vein ran out, which the company then forecast to last for the next 30 to 40 years.

January 1967 “open house” at Hanna Coal Co’s Egypt Valley surface mine, unveiling the GEM of Egypt shovel.

Hanna also used the 1967 mine-opening event to public relations advantage, offering hand-out literature for the public that touted the virtues of reclamation and post-mining uses, some of which bordered on the far-fetched, such as suggesting spoil piles could be used for ski slopes. The reality was that this mine, and others that had preceded it, were ripping through farmland, and despite laws on the books, leaving in their wake, highwalls, spoil piles, acid mine drainage, damaged homes, silted streams and polluted water supplies.

1940s-1960s

Weak Ohio Laws

The state of Ohio has not had a happy environmental history with strip mining; and to this day, its ravages are still taking a toll. Although Ohio was one of the earliest states to adopt a strip mining law in 1947-48, that law had very little impact in terms of environmental protection or land reclamation. As documented in Chad Montrie’s book, To Save The Land and People, Ohio farmers were among the first to rail against the ravages of strip mining.“We believe that strip mining is a menace to agriculture and the very life of our county, unless some control measure is taken.”

-Morgan County Grange, 1947 Farm groups such as the Grange and Farm Bureau, concerned about losing good farmland to the strippers, helped pass the Ohio law in 1947. Wrote one member of the Morgan County Grange in 1947 in support of Ohio’s first strip mine law: “We believe that strip mining is a menace to agriculture and the very life of our county, unless some control measure is taken.” A member of the Western Tuscarawas Game Association, also supporting the legislation that became law, noted: “Strip mines must level their spoil banks and the land put in a tillable condition.” But despite the 1947 law, that wasn’t happening, and didn’t happen. Essentially, there was no reclamation.

1940 post card from the Cadiz News Agency, with four photos by E.C. Kropp Co., showing coal mining scenes near Cadiz, Ohio, Harrison County with caption: “Scenes From Cadiz, Ohio. Where They Destroy Good Farms to Get The Coal.” Some stripping shovels at that time were mounted on rails and/or temporary rail lines & hopper cars serviced the mining area.

By 1949, the Grange and Farm Bureau were back in the legislature seeking strengthening amendments to the law. Still, little changed. In 1953, the Conservation Committee of the Ohio Grange noted that “land in the strip mining areas of Ohio [is] left in such condition that it is practically worthless.” By 1965, the Grange and Farm Bureau again lobbied the Ohio General Assembly for tougher strip mine regulations, but only minor changes resulted.“Land in the strip mining areas of Ohio [is] left in such condition that it is practically worthless.”

-Ohio Grange, 1953 Some of the adopted language now called on coal operators to grade spoil banks “so as to reduce the peaks thereof …to a gently rolling, sloping or terraced topography, as may be appropriate, which grading shall be done in such as way as will minimize erosion due to rainfall, [and] break up long uninterrupted slopes.” Large boulders were also to be removed and acid mine drainage and stream siltation on adjacent lands prevented, “if possible.” Needless to say, such language wasn’t exactly iron clad. Farm organizations by then were filing reports of strip mine siltation and clay washing onto adjacent lands in depths of up to two feet. They called on legislators to deny strippers their license when they damaged neighboring lands. But that didn’t happen either. Further reform wouldn’t come until 1972, covered later below.

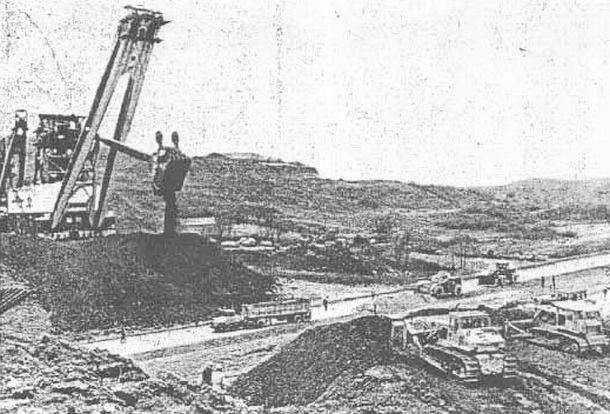

During the late 1960s, meanwhile, The GEM of Egypt was chewing through Ohio farm country at a rate of 200 tons per bite, continuing to work through the Egypt Valley of Harrison and Belmont counties where Hanna held thousands of acres of land with strippable coal. The GEM gradually worked its way to within sight of the interstate highway, I-70, as it dug through the hills just north of the highway. Motorists traveling on I-70 would sometimes stop to marvel at the giant shovel while it did its handwork.

The Gem of Egypt working its way through the Egypt Valley strip mine of Ohio in the late 1960s early 1970s. The giant machine is removing the earth over the coal seam on the right, and then, swinging its boom and loaded shovel left, depositing the “overburden” on the spoil banks. A tiny vehicle mid-photo appears to be riding on a road that is the unearthed coal seam. At right, atop the hillside being mined, is a line of powdered-white blasting holes where dynamite will be used to loosen the “overburden” the giant shovel will continue to remove.

Hanna, at this point, had new plans for The Gem of Egypt. Hanna wanted to use the machine ten miles south, to begin stripping coal lands near Barnesville, in Belmont County. Barnesville then had a population of 4,300. But in order to move the big machine to that location, it would have to cross, and temporarily shut down, a major interstate highway, I-70. While Hanna and other coal companies had worked their will with local and state roads – sometimes taking them over completely for hauling coal, or taking them out of service – a federal interstate highway was in something of a different league. And this particular east-west segment – running between Wheeling, West Virginia and Columbus, Ohio – would become heavily traveled.

The I-70 Deal

In the 1950s and 1960s, as President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s Interstate Highway system was taking form across the U.S., one of the segments to be built in Ohio was the East-West running Interstate I-70. This highway would cut across Southeastern Ohio’s coalfields, including counties in the vicinity where Hanna and others were operating. Hanna, in fact, had acquired some 12,000 to 13,000 acres of coal lands (more??) in the area prior to the laying of the I-70 route. So when the Federal and state governments started planning for I-70, Hanna was one of the parties at the table– and by that time Hanna was part of Consolidated Coal Co., or Consol.

Map showing I-70 running through a portion of S. E. Ohio near the town of Barnesville, where strip mining was headed in 1973.

Consol claimed $8-to-$10 million in damages for the dividing of its coal field by the highway. However Ohio agreed to construct two underpasses at I-70 to permit Consol’s coal trucks to travel under the highway. The state also agreed to permit Consol to cross over the surface of the I-70 highway with mining equipment 10 times during a period of 40 years. The U.S. Secretary of Transportation also approved this agreement in early September 1964.

By 1968, Interstate highway I-70 was built, with about 27 miles traversing Belmont County, bisecting the coal lands held by Hanna/Consol. During this time, Hanna’s Gem of Egypt and the strip mining of the Egypt Valley site had proceeded, moving closer and closer to the Interstate.

1960s-1970s

New Activists

Through 1967, the Ohio farm groups continued to seek stricter strip mine enforcement in the state legislature, though with little success. By this time, however, new public environmental awareness was rising across the nation and in Ohio, where the Cuyahoga River had caught on fire from pollution in June 1969, raising the state’s environmental profile. New activists were entering the strip mine fight there as well, and throughout the region. A 1970 strip mining symposium held in Cadiz, Ohio drew 400 attendees, including many students, but with sponsors such as the Ohio Conservation Foundation, state chapter of the Sierra Club, the Ohio Audubon Council, and others. By late December 1970, some local members of the United Steelworkers Union and the Belmont County AFL-CIO, along with others from Ohio State University’s Marion extension campus, formed an organization called Citizens Concerned About Strip Mining. This group planned to lobby the Ohio legislature for strip mine reforms, and in the summer of 1971, sponsored a meeting that drew prominent strip mining opponents from nearby states, including a regional representative of the Sierra Club.

|

“The Ravaged Earth”  Title screen for “The Ravaged Earth” TV program pro-duced by WKYC-TV, Cleveland, 1969. Click for film. In Cleveland, a small group of TV producers and writers at NBC’s WKYC-TV station, produced a 1969 documentary that focused in part on strip mining in Ohio’s Perry County and the environmental ruin it was causing there. The film was part of WKYC’s Montage series of documentary programs on local and regional subjects that aired in Cleveland from 1965 to 1978. The title of the strip mine program was “The Ravaged Earth.” Linda Sugarman, one of the associate producers at the time, wrote a July 31, 1969 memo, statement of need, and description of the planned program, to be broadcast in late September 1969: For twenty five years giant steamshovels have been clawing their way across the beautiful hills of Southern Ohio, unearthing shallow veins of coal and leaving a scene of utter devastation. The strip mines, which are dug instead of deep mines when the coal is close to the surface, bring about in their wake a stark, and almost worthless wasteland of steep spoil banks whose overturned earth is so acidic weeds can barely grow on it. Rivers and streams become red with sulfuric acid pollution. Public heath hazards are created by uncontrolled clouds of coal dust and carbon monoxide fumes. Property damage, caused by blasting goes uncompensated. Many of the mining interests seem to be in almost total disregard of the local laws, property rights, safety, and health of the nearby residents. Although a few of the coal companies attempt to renew and reclaim the land they have strip mined, the ones who have made so much damage seem to be able to continue their activities without much opposition. Since the coal companies bring in most of the income in many of these counties, most public officials seem hesitant to prosecute or even confront them. Residents of the area who depend directly or indirectly upon the mines also seem hesitant to complain about the coal companies’ actions… Montage will talk to these conservationists, as well as local citizens, elected officials, and mine representatives. The film will also show the damaged as well as the reclaimed areas of Southern Ohio.  Screen shot from “The Ravaged Earth” of light green automobile (center) moving through unreclaimed strip-mined area with remaining highwall, spoil debris, and rugged terrain. In fact, Udall, who served as Interior Secretary from 1961-1969, made extensive comment during the program. Below are excerpts from his remarks and voice-overs during that program:  Stewart Udall, as he appeared in the 1969 TV report, “The Ravaged Earth.” “Coal as an extractive industry, like all extractive industries, once the mineral or product is mined, the values are gone, and the industry usually walks away and you’re confronted then with the long haul with what people will do with what is left…” “…We calculated once in a strip mine study we made about two years ago what the cost would be of restoring all the stripped areas in the United States. As I recall it was a very big cost, something like $2 billion…And it’s also an uneconomic cost because this should have been done at the time the coal was mined and should have been charged as part of the cost of the mining… So I fear this [reclamation] will have a very low priority, that it will not be done in the near future, and the result is that we’re going to be denied the use and benefit of these lands for recreation,“…[T]here’s no damage to the land that is more permanent, and really more devastating, than what you see in the worst strip mining areas of the United States…” “…I’ve probably seen as much of this nation from a helicopter in the last 6 or 8 years as anybody – and that’s the best way to see it.. Because you see the beauty, you see the scars, you see the damage. And of course, there’s no damage to the land that is more permanent, and really more devastating, than what you see in the worst strip mining areas of the United States… The reason this is damaging is that if action is not taken to restore these stripped areas, they’re left there; they can’t revegetate themselves — at least it will take many, many tens or hundreds of years for anything to occur… And that these become sort of permanent, man-made wastelands. …We have too many people; we have too many things we need to do with our land; too much need for outdoor recreation and playgrounds…We can’t afford to have wastelands created by man in this country. And this is the reason all of us have to regret the mistakes of the past and we have to determine that we’re not going to repeat those mistakes now.” All in all, WKYC-TV’s “The Ravaged Earth” was one of the first of its kind on strip mining, and helped educate the public about what was happening in the coalfields. |

In the Ohio academic community, meanwhile, Arnold Reitze, from Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, wrote a 1971 law review article entitled, “Old King Coal and the Merry Rapists of Appalachia,” in which he focused on some of strip mining’s effects in the Egypt Valley where Hanna was mining. Reitze found that in Belmont County, some 200,000 of the county’s 346,000 total acres had been sold, leased, or optioned to coal interests. “That beautiful county,” he wrote, “like scores of others, seems destined to become a wasteland of silted, acid waters, barren land, and patches of crown vetch, all legally reclaimed.”New activists and a new governor were changing Ohio’s strip mine politics. Another professor who became involved was Dr. Theodore “Ted” Voneida, a professor of neurobiology also at Case Western. Voneida and his wife had built a cottage on Piedmont Lake in the Egypt Valley in the 1960s and soon began to see first hand the results of strip mining in that area. Voneida didn’t like what he saw, and was amazed at what the strippers were doing to the land and communities. He began gathering documentation of strip mining’s impacts in the area – measuring water pollution, taking photographs, and generally chronicling what was going on there. He also succeeded in getting The Plain Dealer newspaper of Cleveland, the Akron Beacon Journal, and others news outlets interested in the strip mining story. By the early 1970s, Voneida would be quoted in newspaper stories on strip mining’s harmful effects, sometimes opposite Hanna Coal’s CEO, Ralph Hatch.

New political developments in Ohio also brought more attention to the lack of effective strip mine reclamation. John J. Gilligan, a democrat from Cincinnati who had served in the U.S. Congress for one term in 1965-1967 and had run unsuccessfully for the U.S. Senate, was elected Ohio’s Governor in November 1970 (Gilligan was also the father of Kathleen Sebelius, who would later serve as Governor of Kansas and U,S. Secretary of Health and Human Services in the Obama Adminstration). Governor Gilligan took on strip mining as one of his top priorities, and he specifically backed a bill in the legislature that would bring tougher reclamation standards to Ohio’s coalfields.

Hanna Coal, meanwhile, made plans for mining south of I-70 and sought to exercise its highway crossing agreement with Ohio and the federal government. However, by late 1970, Hanna, and strip mining in Ohio, were getting some unwanted national attention, now cast in an Appalachian regional and national context over how best to deal with surface coal mining. And Hanna’s hulking machines were part of the theater – and the damage being done.

Ohio in Spotlight

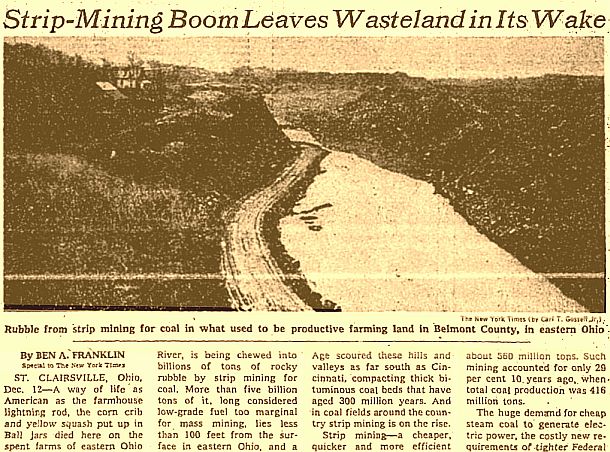

On December 15, 1970, Ben Franklin, a reporter with The New York Times, did a story on strip mining that his editors ran on the front page with a photo of a ravaged Ohio strip mine scene. “Strip-Mining Boom Leaves Wasteland in Its Wake,” was the headline. Franklin filed his story from St. Clairsville, Ohio. And while the story covered strip mining nationally, it featured particular problems in Belmont County, where Hanna was then operating day and night.

Dec 15, 1970: Front-page story in the New York Times with photo of strip mine damage in Belmont County, Ohio and story that prominently featured Ohio strip mining, environmental issues there, and the Hanna Coal Company.

In his story, Franklin described the strip mining problem in Ohio as follows:

…This rolling, unfarmed farm land, just west of the Ohio River, is being chewed into billions of tons of rocky rubble by strip mining for coal. More than five billion tons of it, long considered low-grade fuel too marginal for mass mining, lies less than 100 feet from the sur face in eastern Ohio, and a boom is on to recover it.

It is bringing an upheaval of terrain unmatched since the glaciers of the last Ice Age scoured these hills and valleys as far south as Cincinnati, compacting thick bituminous coal beds that have aged 300 million years…

“They’re turning this beau-tiful place into a desert…”

– U.S. Rep., Wayne L. Hays (D-OH)

Strip mining—a cheaper, quicker and more efficient method than digging under ground—now produces more than 35 per cent of the nation’s annual coal output…

…To lay bare the coal, farms, barns, silos, houses, churches and roads are being dynamited, scooped up by mammoth power shovels that tower 12 stories high, and piled in giant windrows of strip mine spoil banks.

Scores of aggrieved persons here have lost well water, have suffered sleepless nights from blasting, or have seen timbered acreage at their property lines turned into the 100-foot-deep pits of strip mines.

In his story, Franklin also quoted U.S. Congressman Wayne L. Hays, an Ohio Democrat who then lived in Flushing, Ohio, a Belmont County town which Franklin described as “isolated on three sides by abandoned strip mine highwalls, the sheer, quarry-like cliffs where the strip mine excavation stopped.” Congressman Hayes, cited in Franklin’s story, had this to say: “They’re turning this beautiful place into a desert … They’ll take anything that’s black and will burn… It costs them more to really reclaim this land than the land is worth when they’re finished. No one has figured out what will happen to us here when they’re through, but I can tell you it isn’t going to be pretty.”

The GEM of Egypt at work in Ohio, circa 1960s-1970s, also illustrates the problem of “highwalls” – the sheer-face cliffs, seen here on the right – often left as unreclaimed “final cuts” when the mining was finished.

During 1970, environmental concerns continued to rise across the nation. On December 20th that year, President Richard Nixon established the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). In the strip mine fight, just after Christmas 1970, West Virginia’s Secretary of State, Democrat John D. “Jay” Rockefeller announced that he would seek a ban on the surface mining of coal in West Virginia, with bills to that end introduced in the legislature in late January 1971. At the federal level too, by July 1971, West Virginia’s Congressman, Democrat Ken Heckler, had introduced legislation in the U.S. House of Representatives to ban surface coal mining. The prohibition efforts, however, at state and federal levels, would prove to be uphill fights.

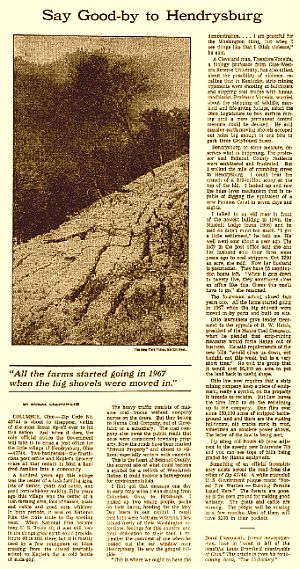

A New York Times Op-Ed by Belmont County, Ohio resident brought further attention to the impact of strip mining on Ohio’s land and small towns.

As the article contended, Hendrysburg would be ruined as a viable small town given what the strippers were doing to depopulate the area, having bought out many landowners. A pull quote used in the piece noted: “All the farms started going in 1967 when the big shovels were moved in.”

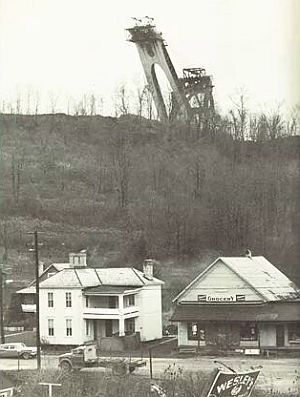

Barely a town by that point, Hendrysburg had been badgered day and night for several years by the hulking operations of The GEM of Egypt. Blasting and digging to get at the coal — as well as 100-foot-deep excavations made around and near the town — had unnerved residents. Wells were disrupted in some places. And since the shovel worked around the clock with lights, the town’s homes were sometimes “bathed in an eerie electric glow,” as one reporter described it.

Florence Bethel, a Hendrysburg resident who worked as a telephone operator, had first-hand experience with The GEM of Egypt. She later recounted her tale to reporter George Vescy of the New York Times:

“It started around Christmas of 1969. You could feel the blasting three and a half miles away. I had a brand new sealed well, 53 feet deep. The water got so muddy, it clogged the valves. Then my basement walls cracked. …I was working nights and trying to stay in college. I couldn’t sleep during the day. I called them up and asked them to take is easy, but it just got worse. Then my health started to go. I had a 3.2 average but it dropped to D’s and F’s. I had to drop out….” Bethel sued Hanna for $107,500 and damages and moved to a mobile home south of Barnesville.

In February 1972, a two-day strip mining conference at Zanesville, Ohio attracted about 100 activists. Also that month, on February 26th, the Buffalo Creek disaster in West Virginia occurred. In the upper reaches of the Buffalo Creek watershed in Logan County, West Virginia, a series of large coal slurry waste gop impoundments burst after heavy rains, releasing a tidal wave of coal waste water on more than a dozen downstream communities. More than 125 people were killed, with at least 1,000 more injured and 4,000 left homeless. Upstream strip mining and mine wastes were implicated as contributing factors.

New Law

In March 1972, Ohio Governor John Gilligan, addressing the state legislature in opening his administration, listed strip mining legislation as among his priorities. As the new Ohio state strip mine bill was being considered in early 1972, among those coming to testify was Mrs. Alice J. Grossniklaus, of Holmes County, Ohio. Mrs. Grossniklaus had a cheese store near Wilmot, Ohio that she had run since 1932.“…They’d call me at 2 or 3 a. m. and tell me that their cupboard doors were opening and closing from the blasting, flower pots were falling off the walls, and that the walls were cracking…” In the early 1960s, she had her first experienced strip mining on about 1.000 acres of land in nearby Tuscarawas County. She would explain that the mining was driving some of the neighbors crazy. “They’d call me at 2 or 3 a. m. and tell me that their cupboard doors were opening and closing from the blasting, flower pots were falling off the walls, and that the walls were cracking. ‘What can we do, they would ask.’ I told them to call up the mine owners and get them out of bed so they could be bothered too.” Grossniklaus had crusaded for tougher strip mine laws since 1963. “Until then, I didn’t even know what a strip mine was,” she would say. But in March 1972, she drove to Columbus to testify before a Senate committee on the pending strip mine legislation, calling for the strongest possible bill. Ted Vonieda testified on the pending bill as well. He recommended a three-year ban on strip mining until a detailed study could be made of strip mining’s environmental impact on the state.

The new Ohio strip mine bill, backed by Governor Gilligan, was passed and took effect on April 10, 1972. But it wasn’t clear how much the new law would help those in Belmont County facing the expansion of strip mining south of I-70, as the giant shovel prepared to cross the interstate. Local newspapers were reporting that the crossing by The Gem of Egypt could occur before June 15, 1972, ahead of the summer vacation season when traffic on I-70 would be at a peak levels. Local activists, however, were vowing to fight the crossing.

The Crossing Fight

Among local residents who were opposed to the I-70 crossing was Barnesville City Council member Richard Garrett. After a couple of residents had come to him when strip mine blasting had damaged their homes, Garrett formed Citizens Organized to Defend the Environment (CODE) in June 1971, a grassroots effort aimed at the environmental impacts of strip mining.

The local opponents, however, were outnumbered by those who saw coal mining as key to their local economy and those who worked directly at the mines. During a summer 1972 public meeting sponsored by CODE in Barnesville, part of which was captured by an ABC-TV documentary, Echo of Anger, some of those working at the strip mines came out to offer their opinions.“…If that GEM is not able to cross the road, I’m out of a job…[I]f they keep the publicity up on this thing [i.e., the crossing], we are going to boycott the busi-nesses in town…”

– Bernard Delloma, mine worker A bulldozer operator working at the Egypt Valley Mine, Bernard Delloma, voiced his objection to the lawsuit filed to stop the crossing. “If that [mine] shuts down, there are 322 of us [out of a job]. If that GEM is not able to cross the road, I’m out of a job. I’m out of a ten or twelve thousand dollar a year job.” And he added that he and the other strip miners “have organized… and we say that if they keep the publicity up on this thing [i.e., the crossing], we are going to boycott the businesses in town. If we do, there won’t be no town left.”

“I don’t like stripping or any part of it,” explained Barnesville furniture store owner John Kirk, quoted in a Wall Street Journal story. Kirk, in fact, had gone to Columbus to protest new mining regulations. Still, “it isn’t that simple,” he said. “Better than 10 percent of the work force in this county works for the mines.” Newspaper editor Bill Davies of the Barnesville Enterprise agreed, “Our future is definitely tied to the strip mining industry – it’s more important to us that you think.”

Map shows approximate location in Ohio of a planned I-70 crossing by a giant strip-mine shovel owned by the Hanna Coal Co. N.Y. Times map.

Meanwhile, a permit for the crossing of I-70 by The GEM of Egypt strip mining shovel was issued to Hanna/Consol on August 7, 1972. That’s when the CODE group joined the Ohio Public Interest Research Group (PIRG) in a lawsuit to challenge the I-70 crossing. Garrett in comments to the Times-Leader newspaper of Martins Ferry, Ohio, had stated earlier his group’s intent “to fight every one of those machines when they try to bring them across.” The lawsuit was filed in federal district court. CODE was joined by Friends of the Earth and two local residents as listed plaintiffs

The legal battle would delay any further action on the crossing. Still, on September 29, 1972, Hanna/Consol moved to amend the crossing permit to substitute The Mountaineer and The Tiger (also known as 46-A) shovels, instead of The GEM of Egypt. Some speculated this was partly a public relations move on Hanna’s part, since the bigger GEM of Egypt had drawn national notice at the time. But Hanna’s CEO, Hatch noted that The GEM had plenty to do north of the interstate and would make the crossing later in 1973 or early in 1974.

In their legal challenge to the crossing, CODE and fellow plaintiffs made federal and state arguments. They raised questions of federal procedure and decision making under the Administrative Procedures Act; whether the U.S. Secretary of Transportation could approve such a crossing under the Federal Highway Act; and whether the action to cross might be construed to be “a major federal action” under the National Environmental Policy Act requiring an environmental assessment.

From Associated Press story, December 29, 1972, Observer-Reporter (Washington, PA).

On each of these counts, U.S. District Court Judge Joseph Kinneary in Columbus offered his findings and analysis, and on December 15th, 1972 he dismissed the plaintiffs’case and allowed the crossing to proceed.

In his ruling, the judge cited as valid the 1964 shovel-crossing agreement the company had made with Ohio and the Federal highway agencies. He did note that the crossing of 1–70 would be an “inconvenience,” but one that would only slow traffic and not stop it, with suitable detours. Hanna would, however, be liable for any damage to the highway. So with Judge Kinneary’s ruling, the crossing was allowed to proceed.

One protest group, The Commission on Religion in Appalachia, from Knoxville, Tennessee, made an 11th-hour appeal to Ohio Gov. Gilligan to step in and halt the crossings. But the giant shovels would not be stopped. Still, a coalition of protesters from Ohio, Kentucky and West Virginia planned a peaceful march to the crossing site.

The Crossing

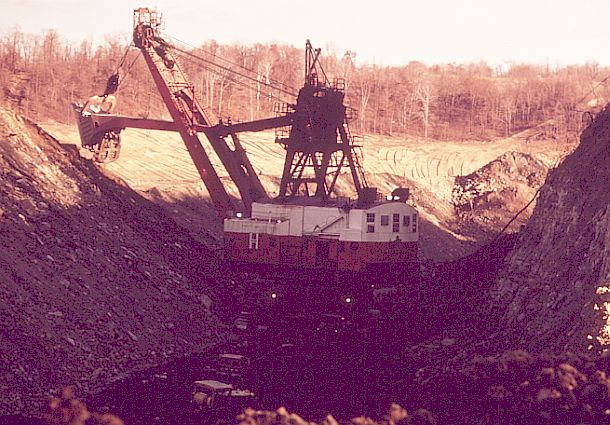

On January 4, 1973, in the early hours of a bitterly cold winter morning, the two mammoth machines – first, the 5.5 million pound Mountaineer (65 cu yd bucket) followed by the smaller, 4.5 million pound Tiger (46 cu yd bucket) – crossed I-70. The machines moved very slowly in making the transit, at a rate of about three miles an hour.

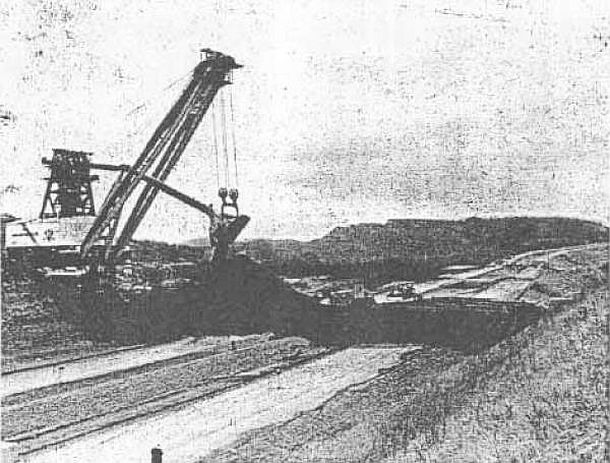

Grainy black & white photo of The Mountaineer shovel at left moving toward its crossing point of Interstate highway I-70 near Hendrysburg, Ohio, dumping sand ahead of itself as part of the land bridge being built to protect the highway surface from damage.

The crossing required a rerouting of traffic off I-70 for approximately 1¼ miles. Temporary entrance and exit ramps in both directions were constructed, connecting with State Route 800 onto which traffic was routed for a mile or so, until it could return to I-70. Uniformed flagmen were stationed to direct traffic through the re-routing. To protect the highway pavement, a special gravel and earthen land bridge was built across I-70 over which the Hanna shovels crossed. At least six feet of crushed stone and earth was used for the land bridge and heavy wooden mats were also placed over the crushed stone and earth. Sensors were also placed beneath the highway surface to test for any stress on the roadway.

The Mountaineer shovel shown continuing to aid in the construction of the land bridge upon which it and another shovel, The Tiger, would cross interstate highway I-70 in Ohio in order to strip mine coal fields on the other side.

A fleet of some eight bulldozers worked around the base of the big shovels, helping to shape and stabilize the land bridge ahead of the crossing. The transit of the big shovels began at noon on January 4th, 1973. Under the permit, Hanna was allotted a period of 24 hours to move its equipment, and officials at the company had estimated it would take from two to three hours to make the actual crossing. However, the crossing was made ahead of schedule and was actually completed by 6:30 pm that day.

The crossing of the big shovels made The NBC Evening News with John Chancellor on Friday, January 5th, 1973. The event was also front-page news in many Ohio newspapers, and was also covered in the New York Times and Washington Post. One local newsman rode along in The Tiger as that shovel made the crossing.

Jan 4, 1973: The Mountaineer earth-moving shovel makes the transit across I-70 near Hendrysburg, Ohio, on its journey south through Belmont County to help strip mine coal lands owned by Hanna Coal Co. near Barnesville.

Ted Voneida of Case Western Reserve University was one of the activists at the crossing. He was quoted in an Associated Press story on the day of the crossing: “I’m protesting the idea that we must trade off the environment for [electric] power in this country. I hope to let people know, especially in the western states, what is happening.” Strip mining was then about to move west in a big way, to states such as Montana and Wyoming, where the land was flat to gently rolling, the coal seams thick, and the odds against reclamation even greater. Voneida was sounding a warning: the giant shovels were headed their way and the results would not be pleasant. Other protesters at the crossing – all peaceful; there were no confrontations – sought to highlight the fact that costs were being created — costs to roads, water, and land — that would be borne by the public, not the companies making the profits.

On January 5th, 1972, after the two shovels were moved across the highway, Arthur Wallace, who then headed Hanna’s reclamation efforts, conducted a bus tour of “reclaimed” areas for newsmen, as a contingent of press from out of state had gathered for the crossing. Wallace noted that Belmont County’s’ farming land, after strip mining, would be used for cattle grazing due to the lower quality of the restored land. Wallace noted that the cattle would graze on a variety of vegetation including alfalfa and crown vetch.

Postscript

Once on the south side of I-70, The Mountaineer and The Tiger resumed their digging as Hanna/Consol continued strip mining in Belmont County for many years. And despite the new 1972 Ohio strip mine law (the implementation of which was blocked for several years by coal company litigation), Hanna’s Egypt Valley Mine continued its southward expansion, as the big shovels worked to turn the landscape upside down. True, some reclamation occurred in that area and throughout the state, and the land in some cases was returned to passable condition. But environmental problems from strip-mined land, and disruption for nearby communities, persisted for many years throughout the coal mining areas of the state, continuing for some areas as this is written.

The Tiger at work uncovering coal seams near Barnesville, Ohio in 1973 after it had crossed interstate I-70.

But during the 1970s, in the Belmont County area and other Ohio counties, there appears to have been continued struggle between local residents and coal mining companies. Among those residents, for example, was Mary Workman of Steubenville, Ohio (shown below) who would not sell her land to Hanna Coal Company even though the company owned much of the land around her and many of the local roads were closed. In the early 1970s, she filed a damage suit against the Hanna Coal Company for ruining her water (still searching for the outcome of that case).

Photo date, October 1973. Mary Workman of Steubenville, Ohio holds a jar of undrinkable water that comes from her well. At the time, she had filed a damage suit against the Hanna Coal Co.; she had to transport water from a well many miles away. She also resisted selling her land to the coal company, even though much of the land around her was sold and many of the roads closed. Photo, Erik Calonius, U.S. EPA Documerica Project.

By August 1977, the federal Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act was signed into law by President Jimmy Carter, providing hope in the nation’s coalfields for improved regulation and better reclamation outcomes. Among those invited to the Rose Garden signing ceremony was Barnesville’s Richard Garrett and Case Western Reserve University’s Ted Voneida. Yet even with the 1977 federal law, which did help raise mining safety and reclamation standards across the country, the record now 40 years later remains mixed, with the law’s Abandoned Lands Reclamation Fund a frequent target of the industry, and in 2017, slammed by an Inspector General’s report for diversions of reclamation monies in some states for non-reclamation purposes.

The Sand Hill strip mine in Vinton County, Ohio, May 2008, as photographed by Ohio’s Matt Eich for his book “Carry Me Ohio,” and also published in The Atlantic magazine, December 2016.

In southeastern Ohio, meanwhile, strip mining, and the region’s reliance on a single industry, has not made for a viable economy. As Allen J. Dieterich-Ward noted of the region, writing in his 2006 dissertation, Mines, Mills and Malls: Regional Development in the Steel Valley:

…By the late 1970s, the rise in mining employment coupled with the failure significantly to diversify employment or to develop the region’s infrastructure meant that the area’s economic fortunes increasingly rested on a single industry. The continued use of surface mining had also depopulated large swaths of the area, leaving behind thousands of acres unsuitable for either industrial or recreational development. The collapse in the market for the area’s high sulfur coal during the 1980s prompted a steep drop in mine employment. Combined with losses in the heavy industrial employers along the Ohio River, the mine closures created a mass exodus from the region and the collapse of the local economy.

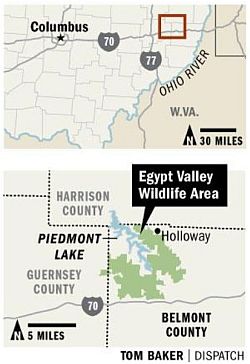

Columbus Dispatch newspaper map of the Egypt Valley Wildlife Area in S.E. Ohio.

Elsewhere in the region, some of the land where Hanna’s monster shovels roamed, ironically, has been converted into parks and wildlife areas. In Harrison County, the surrounding hillsides of what is now the Sally Buffalo Park were strip mined for coal in the 1950s. Hanna had also built a dam there in 1953 to “reclaim” some of the mined land, and the area was first used as a recreation area for company employees. The restored area became a public park in 1965.

The 18,000-acre Egypt Valley Wildlife Area was created by the state of Ohio in 1994-95. It includes land in the northwest corner of Belmont County where The GEM of Egypt worked for a number of years. Approximately 80 percent of the acreage in the Egypt Valley Wildlife Area has been strip mined. The last active mine there was completed in 1998. The converted wildlife area, however, as of 2015, has been targeted for coal re-mining. Oxford Mining Co. a subsidiary of Westmoreland Coal Co, won a 2015 case before the Ohio Supreme Court allowing it to strip mine there. Given this decision (which involved a privately-held in-holding), other Ohio parks, forests, and wildlife areas may also be vulnerable to strip mining.

2009 map of abandoned coal mines and unfunded cleanup sites in SE Ohio. Source: Columbus Dispatch.

Abandoned Mines

Part of coal’s legacy in Southeast Ohio continues to be the abandoned mines that have been left behind. As of 2009, the state estimated that more than 600,000 acres of coal had been mined underground in Ohio and more than 720,000 acres had been strip mined. The Columbus Dispatch map at left shows those areas of known mine sites – underground and stripped – that have been abandoned, as well as unfunded cleanup sites.

In 2012, a Columbus Dispatch story on coal and polluted streams in the state, noted: “Coal’s legacy on Ohio’s waters, particularly in the southeastern part of the state, is visible in creek after yellow creek. In some instances, coal companies intentionally pumped water out of coal mines into nearby streams. In others, abandoned coal mines that fill with rainwater continuously leach water into nearby watersheds.” Some 1,300 miles of streams or creeks in Ohio have been polluted by water from coal mines.

Scientists and citizen organizations in Ohio have initiated some remediation efforts in a few watersheds that have been heavily mined. One of these has been a partnership working to restore the Raccoon Creek watershed in southeastern Ohio. This watershed with multiple streams drains 683 square miles of land in six counties: Athens, Gallia, Hocking, Jackson, Meigs, and Vinton. Coal extraction over nearly 100 years in the area has badly damaged the watershed. On a map of the watershed below, strip-mined areas are indicated in dark blue, while deep-mined areas are shown in red.

In the early 1950s, Ohio’s Division of Wildlife performed the first study of the Raccoon Creek basin and found little aquatic life due to abandoned coal mines and acid-producing wastes. Some 350 million tons of coal were mined in this watershed between 1820 and 1993, affecting nearly 40,000 acres.

Blue (stripped), red (deep-mined), 6-county Raccoon Ck. watershed.

As of 2005, however, Ohio scientists believed that it would still take a decade for recent remediation efforts in the watershed to have any pronounced changes on the water quality and biology of its streams. A number are still in poor or fair condition. But in a few streams, there have been improvements in water chemistry and aquatic habitat. Findings of aquatic insects and fish in Little Raccoon Creek, for example, while not in great numbers, show a diversity that some scientists find promising for the future.

Big Shovel Epitaphs

As for the monster machines that caused all the damage and commotion back in the 1960s and 1970s, all three of them had long mining careers. The Tiger, from 1944, worked up through the 1970s; The Mountaineer, began working in 1956, stopped digging in 1979 and was scrapped in 1988; and The GEM of Egypt of 1967, dug its last shovelful in 1988. The Silver Spade, a sister shovel to The GEM, and also used by Hanna, continued mining though January 2006, in part because The GEM was used for parts to keep The Spade running. More history and background on the big machines, and Ohio’s surface mining history, is available at the Harrison Coal & Reclamation Historical Park in Cadiz, Ohio.

For additional stories at this website on the history of coal and coal mining, see for example, the following: “Ford Helps Strippers…With 2 Vetoes,” (which covers the mid-1970s Congressional battles with the White House and coal industry over strip mine legislation – including a “protest convoy” of more than 400 coal trucks that came to Washington, and two vetoes by President Gerald Ford); “Paradise: 1971″ (about a John Prine song, strip mining in Muhlenberg County, KY, and the issue of “small town removal” by coal mining); “Mountain Warrior” (profile of Kentucky author and coal-field activist, Harry Caudill, noted for his famous book, Night Comes to The Cumberlands and life-long critique of Appalachian strip mining); “Sixteen Tons, 1950s” (the famous Tennessee Ernie Ford song and some coal mining history); and, “G.E.’s Hot Coal Ad, 2005” (a General Electric TV ad that casts coal mining in an unrealistic light).

Thanks for visiting – and if you like what you find here please make a donation to help support the research and writing at this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

____________________________________

Date Posted: 31 May 2017

Last Update: 17 April 2022

Comments to: jdoyle@pophistorydig.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Giant Shovel on I-70: Ohio Strip Mine Fight, 1973,”

PopHistoryDig.com, May 31, 2017.

____________________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

Top of “The GEM of Egypt” shovel stripping hillsides above Hendrysburg, Ohio, early 1970s. Matt Castello/Facebook. |

"GEM of Egypt" shovel stripping hillsides near Morristown, Ohio, north of I-70, 1973-74. EPA Documerica. |

"GEM of Egypt" at work uncovering coal seams in Ohio farm country, circa 1960s-1970s. |

1960s: Aerial view of shovel at work in Ohio and rows of tree/shrub plantings on unleveled spoil piles, lower left. |

Helicopter view: Flying along miles of highwalls in Perry County, OH. From 1969 film, “The Ravaged Earth.” |

Screen shot from “Ravaged Earth” film showing Peabody Coal Co. billboard in Ohio at “reclaimed” site (next photo). |

Eroded spoil piles & mined hillsides on Peabody Coal Co. strip-mined land adjacent to “Green Earth” sign. |

“The Silver Spade” strip mining shovel crossing a local road in Ohio, circa 1960s-1970s. |

"The Silver Spade" -- sister to "The GEM of Egypt," -- was employed by Hanna Coal Co. in Ohio for many years. |

1969's “Ravaged Earth” film showing strip mined lands & environmental dmage in Perry County, Ohio. |

EPA Documerica photo showing some reclamation near New Athens, Ohio, 1973-74, but with remaining highwalls. |

December 1973: Stop sign in southeastern Ohio adorned with a protest message. Erik Calonius, EPA Documerica. |

Jane Stein, “Coal is Cheap, Hated, Abundant, Filthy, Needed,” Smithsonian, February 1973, pp. 19-27.

Associated Press, (Cadiz, Ohio), “Hanna Coal Company Unveils Giant Shovel,” Somerset Daily American (Somerset, PA), January 19, 1967, p. 4.

Douglas L. Crowell, GeoFacts No. 15: “Coal Mining and Reclamation,” Ohio Department of Natural Resources, Division of Geological Survey, Revised, March 2002, 2pp.

“Coal Mines,” Atwater Historical Society (At-water, Ohio).

“Pittsburgh No. 8 Coalfield,” CoalCampUSA .com.

Louise C. Dunlap, “An Analysis of the Legislative History of the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1975,” Proceedings of the Twenty-First Annual Rocky Mountain Mineral Law Institute, Matthew Bender & Co.: New York , 1976.

Chad Montrie, To Save the Land and People: A History of Opposition to Surface Coal Mining in Appalachia, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003.

For an excellent retrospective on the 1970s-1990s history of the strip mining fight, citizen activists involved in that fight, and history on the strip mine law, The Surface Mining Control & Reclamation Act of 1977, see, “Special Issue on the 20th Anniversary of the Federal Coal Law,” Citizens Coal Council Reporter, August 3. 1997.

WKYC-TV, NBC, Cleveland, Ohio, “The Ravaged Earth” (1969 documentary film on strip mining, featuring in part, strip mined lands in Perry County, Ohio and officials from Perry County, commenting on strip mine damage in that county; 21:24 minutes), Michael Schwartz Library, Cleveland State University,

Michael Schwartz Library, Cleveland State University, “Montage: A Filmed History of the 60s and 70s With a Cleveland Perspective.”

James Hyslop, Vice President, Consolidation Coal Company, “Some Present Day Reclama-tion Problems: An Industrialist’s Viewpoint,” The Ohio Journal of Science, Vol. 64, No. 2 (March, 1964), pp. 157-165.

“Hanna Coal: The Early Years” (early mining equipment, 1939-1940s), The Coal Museum .com.

Allen J. Dieterich-Ward, Mines, Mills and Malls: Regional Development in the Steel Valley, A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History), University of Michigan, 2006.

Ben A. Franklin, “Strip-Mining Boom Leaves Wasteland in Its Wake,” New York Times, December 15, 1970, p. 1.

Arnold W. Reitze Jr., “Old King Coal and the Merry Rapists of Appalachia,” Case Western Reserve Law Review, Volume 22, Issue 4, 1971.

Ken Hechler, “Strip Mining: a Clear and Present Danger,” Not Man Apart (Friends of the Earth), V. 1, July 1971 (discusses strip mining and urges support for his bill, HR 4556, which would ban all strip mining six months after its passage).

Interior Committee, House, U. S. Congress. “Regulation of Strip Mining,” Hearings, 92nd Cong., 1st Session, H.R. 60 and Related Bills. Washington, D.C., U.S. Gov’t Printing Office, 1972. 890 pp. Hearings held Sept. 20 – Nov. 30, 1971.

“Hanna Coal to Install Limers on Polluted Skull Fork,” The Daily Reporter (Dover, Ohio), December 27, 1971, p. 17.

Doral Chenoweth, “Say Good-by to Hendrys-burg,” New York Times, Op-Ed page, January 3, 1972.

“Complaints Started Her Strip Mine Fight,” Akron Beacon Journal, (Akron, Ohio) March 1, 1972, p. E-15.

Tom Walton, “Gilligan Lists New Goals Without Asking Extra Tax; New Agency, Strip Mine Bill Get Top Priority,” Toledo Blade, March 1, 1972, p.1.

“Hatch Pledges to Aid Barnesville Leaders,” Columbus Dispatch, March 15, 1972.

“GEM of Egypt Proposed Move: Why Does ‘Earth-Eater’ Cross The Road?,” Akron Beacon Journal (Akron, Ohio), April 2, 1972, p. 32.

“GEM Power Shovel Casts a Shadow Over Barnesville,” Akron Beacon-Journal, April 2, 1972.

GEM of Egypt Photo Gallery, MidwestLost .com.

Editorial, “Ohio Cracks Down on Strip Mining” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, April 22, 1972, p. 6.

“It Could Be A Hungry Vacation For Big ‘GEM’,” Akron Beacon Journal, Sunday, May 14, 1972, p. 6.

“Environment: Why Does the Gem Cross the Road?,” Time, Monday, May 15, 1972.

“Coal,” OhioHistoryCentral.org.

“Suit Eyed to Stop GEM Move,” The Times Leader (Martins Ferry, OH), August 7, 1972, 1.

John S. Brecher, “A Stripper Threatens to Invade Ohio Town; Citizenry is Divided,” Wall Street Journal, August 16, 1972, p. 12.

George Vecsey, “Strip Mining and an Ohio Town: Economy vs. the Environment,” New York Times, September 4, 1972.

“GEM Devastates Ohio Hillsides in Search for Coal,” Denver Post, September 17, 1972.

1972 ABC-TV documentary Echo of Anger (aired mid-August 1972), TV listing: “ABC News inquiry examines the controversial issue of strip mining in the Appalachian region.”

Citizens Organized to Defend Environment, Inc. v. Volpe, 353 F. Supp. 520 (S.D. Ohio 1972), U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Ohio – 353 F. Supp. 520 (S.D. Ohio 1972), December 15, 1972.

Associated Press, “Giant Shovels Due to Cross I-70 in Ohio,” Observer-Reporter (Washing-ton, PA) December 29, 1972., p. 16.

“Bills Regulating Strip Mining Die in Senate,” CQ Almanac, 1972, Washington, DC: Congres-sional Quarterly, 1973.

“Ohio to Shut Interstate a Day for Shovel Crossing,” New York Times, January 1, 1973.

“Environmentalists Plan Protest to ‘Mourn Land’ as Shovels Move,” The Times Leader (Martin’s Ferry, OH), January 3, 1973.

William Richards, “Strip Miners’ Move Alarms Ohio Town,” Washington Post, January 4, 1973, p. A-4.

AP, (Barnesville, Ohio), “Hanna’s Big Shovels to Move Despite Opposition,” The Xenia Daily Gazette (Xenia, OH), January 4, 1973, p. 18.

“Hanna Coal Co. Will Cross I-70; I-70 Is Closed So Crews Can Lay a 12-Foot Blanket of Earth for the Huge Machines to Roll Across,” Columbus Dispatch (Columbus, OH), Thurs-day, January 4, 1973, p. 1-A.

“Mountaineer Goes for A Cruise,” [Thursday, January 4, 1973, The Mountaineer and The Tiger crossed I-70 near Hendrysburg, Ohio. The following pictures are from the January 5 Times-Leader (Martins Ferry and Bellaire, Ohio) and were taken by Boyd Nelson.]

Ben A. Franklin, “Giant Mine Shovels Finally Cross Road; A Vast Operation,” New York Times, January 5, 1973, p. 61.

“Giant Shovels Chug Across I-70,” The Blade (Toledo, Ohio), January 5, 1973, p. 2.

AP, “Shovels Moved Over I-70; As Protestors Watch,” The Evening Review (East Liverpool, Ohio), January 5, 1973, p. 1.

Chan Cochran, “Hanna Coal Company’s Two Huge Strip Mining Shovels Make it Across I-70 Early and Without Incident,” Columbus Dispatch (Columbus, OH), Friday, January 5, 1973, p. 1-A.

“Giant Shovels Cross Highway As Protestors Merely Look On,” The Journal News (Hamilton, Ohio) January 5, 1973, p. 5.

“Hanna Coal Company Moves Across I-70; Ohio Residents Fight Strip Miners,” The Daily Iowan (Iowa City, Iowa), Thursday, January 18, 1973 (Ken Light and Mountain Life & Work contributors).

“Tim Twichell’s Mountaineer Pics,” StripMine .org.

Erik Calonius, Photo Albums (freelance photographer hired for EPA’s “Documerica” Project, 1971-1977 ) Included at this URL are some extensive photos, now in the National Archives, of strip mining and strip mine damage in Southeastern Ohio, circa 1973-74.

“Strip Mining,” CQ Researcher (Congressional Quarterly), November 14, 1973

“Hanna Coal’s Past Recalled in Calendars,” The Times Leader (Martins Ferry, OH), December 17, 2012.

“Coal Mining and Landscape Change: The Case of Harrison County,” OSU.edu.

“Council Pledges Support to Greenbelt Advocates,” Barnesville Enterprise, October 21, 1997.

“Council Approves Greenbelt Resolution,” Barnesville Enterprise, October 22, 1997.

“Warren Trustees Pass Greenbelt Resolution,” Barnesville Enterprise, October 29, 1997.

Ohio Chapter, Sierra Club, “Ohio Tour Shows Effects of Coal Mining,” Sierra Club Scrapbook, December 3, 2008.

Laura Arenschield, “Old Coal Mines Still Taint Ohio Waterways,” The Columbus Dispatch, (Columbus, OH), August 14, 2015.

Allen Dieterich-Ward, Beyond Rust: Metropolitan Pittsburgh and the Fate of Industrial America, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, November 2015, 347pp.

Harrison Coal & Reclamation Historical Park, Cadiz, Ohio.

______________________________________________________