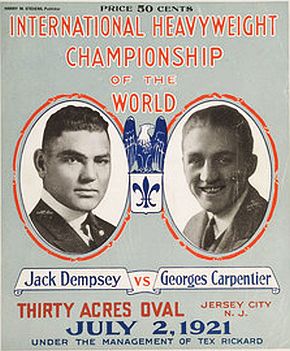

In 1921, they called it “the largest audience in history,” the 300,000 or so people estimated to have heard one of the first radio broadcasts of a special event — the outdoor heavyweight championship boxing match between American Jack Dempsey and French challenger, Georges Carpentier. Dempsey was reigning world champ at the time, and Carpentier was a European boxing champion and decorated French Army veteran. The fight’s promoter had billed the event as the “Battle of the Century.”

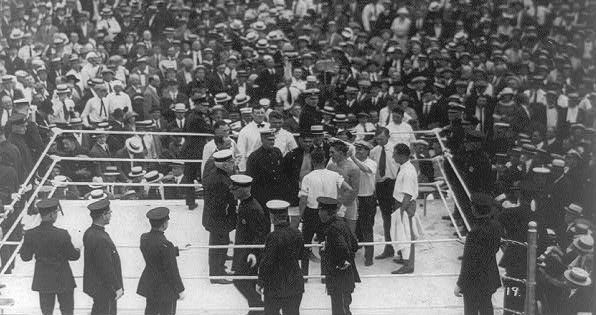

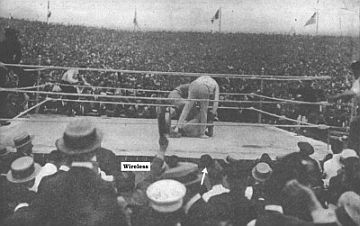

July 2, 1921. Jack Dempsey and Georges Carpentier get ready to square off in championship fight before 80,000 fans. The fight ushered in a 'golden age' of sport in the 1920s, and with radio, the beginnings of sport as mass-audience, big-business entertainment.

A hastily assembled outdoor arena was built on a farm in Jersey City, New Jersey, not far from New York City. More than 80,000 fans came to see the fight in person on July 2, 1921, producing boxing’s first million-dollar gate. Dempsey won in four-round knockout in a scheduled 12-round fight. But the big news for many was the radio broadcast of the fight. It was the first ever broadcast to a “mass audience,” with the blow-by-blow call of the fight from ringside relayed over the new “radiophone,” reaching hundreds of thousands in the northeast U.S. Wireless Age magazine, reporting on the event a few weeks later, described the fight’s call over radio by “a voice that sounded loud and clear throughout the Middle Atlantic states.” It was “history in the making,” said the magazine.

“Hero” vs. “Slacker”

|

|

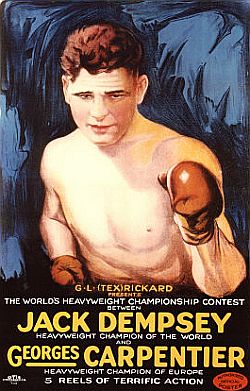

There was also a good deal of hype associated with this fight, as there would be for any major event of this kind. The promoter of the fight, Tex Rickard, cast its principal contestants as “hero” vs. “villain.” The billed “hero” in this case was not the American Jack Dempsey, but rather, the Frenchman, Georges Carpentier, the light-heavyweight champ who had distinguished himself as a pilot in World War I.

Dempsey, on the other hand, was cast as the “villain” as he had been labeled a “slacker” for avoiding the military draft — even though he had been found not guilty of the offense in 1920. Promoter Rickard offered Carpentier $200,000 for the fight and $300,000 to Dempsey — considerable sums for the time — as well an equal share of 25 percent of the film profits. Rickard saw the radio broadcast of the fight as a positive for his future business, and he did what he could to accommodate the new technology at the site. He believed that radio might be a way to advance prizefighting in the post-World War I popular culture. Rickard allowed for a makeshift wooden room for the radio broadcast to be constructed under the stands. Telephone lines and a temporary radio transmitter, sponsored by the Radio Corporation of America (RCA), were installed at the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railway terminal in Hoboken, New Jersey.

David Sarnoff, of the early RCA Company, was among those who saw that the Dempsey-Carpentier fight would help advance radio. (1922 photo).

Radio beyond the reach of a few people had barely begun in the early 1920s. Fledgling operations had started in 1916 in both New York city and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. In Pittsburgh, a Westinghouse employee named Frank Conrad began sending out recorded music played from a phonograph over a radio transmitter set up in his garage. By 1920, Conrad’s employer, Westinghouse, noticed that the broadcasts had increased the sales of radio equipment, which Westinghouse was then manufacturing. The company had Conrad move his transmitter to the Westinghouse factory roof. Westinghouse then applied for a government license and started the pioneer station KDKA, which in early November 1920, began radio programming with the Harding-Cox Presidential election returns. Those broadcasts, however, were only reaching a few thousand hobbyists.

In New York City, too, local radio broadcasts had begun in the fall of 1916 over Lee DeForest’s experimental “Highbridge” station. David Sarnoff, a manger at the American Marconi telegraph company, who lived in New York had heard the early Highbridge broadcasts. Sarnoff wrote a brief memo to the Marconi’s president in 1916-17 about a business possibility for developing a “radio music box” to sell to amateur radio enthusiasts. But nothing came of Sarnoff’s idea at the time. Marconi was then in the heat of WWI. A few years later, however, in January 1920, the Radio Corporation of America (RCA) was established when General Electric acquired American Marconi and Sarnoff, with it. RCA had formed in 1919 after the U.S. Government relinquished control of the wireless industry following World War I.

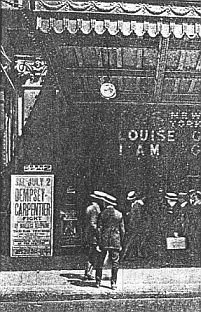

Poster advertising fight at the New York Theater in NY city. Such advertising ran for several days in advance of the bout. This theater would be one of many locations in New York and elsewhere that would fill with listeners on fight day.

The Radio Box

“…For Entertainment”

David Sarnoff, meanwhile, wrote another, more detailed memo on the prospects for radio business and sales to the general public — a 28-page memo titled Sales of Radio Music Box for Entertainment Purposes.

“I have in mind a plan of development which would make radio a ‘household utility’ in the same sense as the piano or phonograph,” Sarnoff began. “The idea is to bring music into the house by wireless,” by which he meant radio.

Sarnoff saw a large potential market, which he then put at about 7 percent of the total families,” yielding a gross return of about $75 million annually in 1920s dollars. Both estimates would soon prove to be very conservative.

“Aside from the profit to be derived from this proposition,” he wrote, “the possibilities for advertising for the company [RCA] are tremendous…” The company’s name “would ultimately be brought into the household,” he said, and radio thereby would receive “national and universal attention.” Indeed it would, and did. But it was the broadcast of the Dempsey-Carpentier fight that would help spark the early public curiosity in the radio and also help the rise of RCA and the radio business. RCA, in fact, made its broadcast debut with the July 2, 1921 championship fight.

Sarnoff also appears to have played an important role in the radio broadcast of the Dempsey-Carpentier fight, although some say the extent of his role has been exaggerated. Still, it does appear that Sarnoff helped make the broadcast possible: he provided money for expenses, a high-powered GE transmitter, and the use of the Lackawanna Railroad terminal antenna in Hoboken, New Jersey.

Cover of the fight program for the July 1921 Jack Dempsey-Georges Carpentier boxing match. |

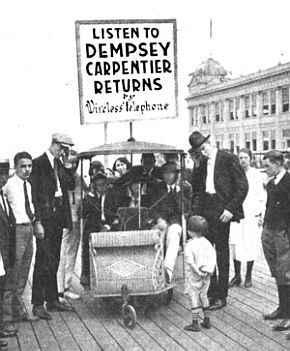

On Boardwalk, Asbury Park, NJ, a “rolling chair” offers passers by a listen to the fight by wireless radio telephone. |

There are also varying accounts as to who initially came up with the idea to do a wide-area radio broadcast of the fight, with some attributing the idea to Sarnoff, and some to others. Julius Hopp, manager of the Madison Square Garden concerts at the time, had observed amateur radio men in more limited venues and was impressed with their descriptions by voice. Some credit Hopp with the idea.

In any case, in April 1921, it appears the idea of broadcasting the Dempsey-Carpentier fight was offered to promoter Tex Rickard and his partner, both of whom liked the idea. There had also been one previous fight broadcast on radio in the Pittsburgh area in April 1921, heard only by a limited number of listeners and radio hobbyists in that location. The broadcast that planners had in mind for the Dempsey-Carpentier fight, however, was for a much broader region.

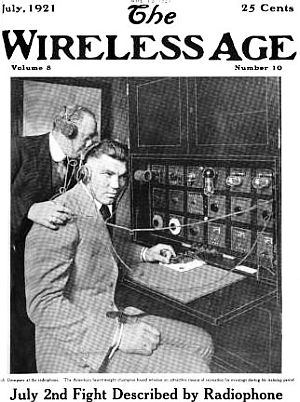

Boxer Jack Dempsey, being introduced to new “radiophone” technology, appears on cover of “The Wireless Age” magazine, July 1921.

An early July edition of Wireless Age magazine described the plan for how the broadcast would work:

…The radio station at Hoboken will be connected by direct wire to the ringside at Jersey City, and as the fight progresses, each blow struck and each incident, round by round, will be described by voice, and the spoken words will go hurtling through the air to be instantaneously received in the theaters, halls and auditoriums scattered over cities within an area of more than 125,000 square miles.

Through the courtesy of Tex Rickard, promoter of the big fight, voice-broadcasting of the event is to be the means of materially aiding the work of the American Committee for Devastated France [i.e., following World War I] and also the Navy Club of the United States. These organizations will share equally in the contributions secured by large gatherings in theaters, halls and other places. The amateur radio operators of the country are to be the connecting link between the voice in the air and these audiences. … Any amateur who is skilled in reception is eligible, whether or not he is a member of any organization.

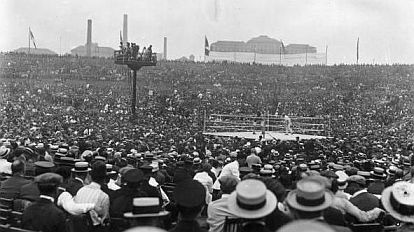

This photo provides a partial view of the huge crowd surrounding the outdoor boxing ring at the Dempsey-Carpentier fight in Jersey City, NJ, July 2, 1921.

On fight day, a notable cast of local and national dignitaries attended the actual event in person. Among politicians and celebrities who joined the 80,000-to-90,000 fans who came to watch the fight were: industrialists John D. Rockefeller, Jr. William H. Vanderbilt, George H. Gould, Joseph W. Harriman, Vincent Astor, and Henry Ford; entertainers Al Jolson and George M. Cohan; literary figures H.L. Mencken, Damon Runyon, Arthur Brisbane, and Ring Lardner; the three children of Theodore Roosevelt — Kermit Roosevelt, Theodore Roosevelt, Jr. and Alice Roosevelt Longworth; prominent Long Island residents, such as Ralph Pulitzer, Harry Payne Whitney and J.P. Grace; Jersey City Mayor Frank Hague; and New Jersey Governor Edward I. Edwards. At the gate, meanwhile, the fans who poured in payed a then-record $1,626,580. It was the first time that a million-dollar amount had been exceeded for a boxing event.

Interest in the fight was keen, as this photo illustrates, showing a crowd of more than 10,000 outside the New York Times building in Times Square awaiting updates.

New York Times photo showing Dempsey standing after a Carpentier knock down.

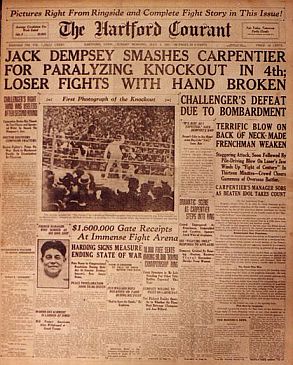

The fight’s results made front-page news across the country, along with the equally big news of the fight’s 1.6 million-dollar gate (in above clip, see headline below photo).

Golden Age

The results of the fight were big news all across the country in the next day’s newspapers — including the fight’s astounding $1.6 million gate. Some historians, in fact, see the fight as a key landmark for the Golden Age of sport that boomed during the 1920s; a Golden Age that also brought expanded media coverage and business promoters like Tex Rickard into the arena, setting sports media on the path to big-business entertainment.

As for radio, other sports broadcasts followed. By August 5th, 1921, the first broadcast of a baseball game was made over Westinghouse station KDKA — a game between the Pittsburgh Pirates and the Philadelphia Phillies from Forbes Field in Pittsburgh. Demand for home radio equipment soared that winter.

By the spring of 1922, David Sarnoff’s prediction of popular demand for broadcasting was coming true, and over the next eighteen months, he and RCA gained in stature and influence. RCA soon went into cross-licensing arrangements with AT&T and Westinghouse, which helped propel the company into a leadership role in both the broadcasting and recording industries.

Ringside broadcaster calling the fight’s blow-by-blow action, then sent out across northeast U.S. from Hoboken, NJ.

1922: 30 Stations

By 1922, there were 30 radio stations in America, and things picked up considerably after that. By late January 1923, programming from New York’s WEAF station was being carried simultaneously over a second station WNAC in Boston, giving rise to the concept of the “network” or “chain broadcasting.”

Less than a month later, on February 2nd, a transcontinental network broadcast link was formed between WEAF in New York and KPO, San Francisco, which was the Hale’s Department Store station. Although New York’s WEAF had featured one of radio’s first paid advertisements in August 1922 — by the Queensboro Corporation using a ten-minute pitch to advertise a new real estate development — broadcasting was not yet supported by advertising.

Most of the early stations were owned by radio manufacturers, department stores trying to sell radios, or by newspapers using them to sell newspapers or express their owners’ opinions.

Photo from ringside also showing part of immense crowd. Carpentier is down for the count here. Radio broadcaster is located at the tip of the white arrow. Photo from, ‘Wireless Age’, August 1921.

Map showing approximate range of the Dempsey-Carpentier radio broadcast in the eastern U.S., reaching a potential audience of 200,000-to-500,000.

Radio historians mark the July 1921 Dempsey-Carpentier fight as one of the landmark events advancing the “radio era” and big-audience communication. And as would become the pattern for other communications technology in the future — whether the Muhammad Ali vs. Joe Frazier fight by satellite TV in 1975, or subsequent global telecasts of World Cup Soccer, Superbowl games, or the Olympics — big sporting events would often be used to introduce or showcase new technology or expanded capability, reaching not just hundreds of thousands, but hundreds of millions and billions. The 2008 Olympics in Bejing, for example, had an estimated total audience of some 4 billion viewers. Special, multi-venue rock concerts and global charity events can now reach billions as well. And online communications only add to these numbers. Still, it wasn’t that long ago when our communications world was a lot smaller; when “big” was a few hundred thousand, as it was on that day in July 1921 when the human voice beamed out over the northeast United States.

Ticket for the Dempsey-Carpentier fight of July 2, 1921, with promoter Tex Rickard’s name at lower right, main stubb.

|

Please Support Thank You |

_____________________________________

Date Posted: 8 September 2008

Last Update: 14 May 2020

Comments to: jdoyle@pophistorydig.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Dempsey vs. Carpenteir, July 1921,”

PopHistoryDig.com, September 8, 2008.

_____________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

1921 poster announcing filmed newsreels of the Jack Dempsey-Georges Carpenteir boxing match. |

“July 2nd Fight Described by Radiophone – The Great International Sporting Event Will Be Voice-Broadcasted from the Ringside By Radiophone Under the Direction of the National Amateur Wireless Association on the Largest Scale Ever Attempted,” The Wireless Age, July, 1921.

“Voice-Broadcasting the Stirring Progress of the ‘Battle of the Century’ – How The Largest Audience in History Heard the Description of the Dempsey-Carpentier Contest Through Use of the Radiophone,” The Wireless Age, August 1921, pp. 11-21.

Carmela Karnoutsos, “Dempsey-Carpentier Fight: Boyle’s Thirty Acres at the Montgomery Oval, Montgomery Street and Florence Place,” Jersey City, Past and Present ( Jersey City, NJ history site), Project Administrator: Patrick Shalhoub.

“Tex Tours Jersey City,” New York Times, April 14, 1921.

“Dempsey Knocks Out Carpentier in the Fourth Round; Challenger Breaks His Thumb Against Champion’s Jaw; Record Crowd of 90,000 Orderly and Well Handled,” New York Times, July 3, 1921.

Ed Brennan, “The Day History Was Made in Jersey City.” Jersey Journal, February 9, 1960.

Lud Shahbazian, “Jersey City Gave Boxing Its First Million Dollar Gate Just 50 Years Ago Today.” Hudson Dispatch, July 2, 1971.

Randy Roberts, Jack Dempsey: The Manassa Mauler, New York: Grove Press, 1979.

Roger Kahn, A Flame of Pure Fire: Jack Dempsey and the Roaring 20s, New York: Harcourt Brace, 2000.

George Mercurio, “The ‘Battle of the Century’,” Jersey City Reporter 16 July 2001.

Alexander B. Magoun, PhD, David Sarnoff Library, “Pushing Technology: David Sarnoff and Wireless Communications, 1911-1921,” Presented at IEEE 2001 Conference on the History of Telecommunications, St. John’s, Newfoundland, July 26, 2001

Thomas H. White, “Battle of the Century: The WJY Story,” January 1, 2000.

“Jack Dempsey Smashes Carpentier,” The Hartford Courant (Hartford, CT), July 3, 1921.

Greg Moore, “Dempsey Cocktail,” Cocktail101.org, November 16, 2011.

Randy Roberts, Jack Dempsey, The Manassa Mauler, 2003, University of Illinois Press, 336 pp (click for copy).