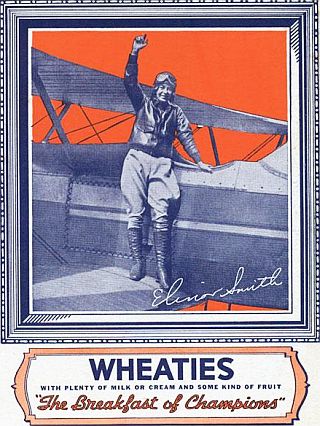

In 1934, Elinor Smith became the first woman to appear on a Wheaties cereal box – then on the back panel. Wheaties would not put a woman on the front of the box until 1984 when gymnast Mary Lou Retton won the honor.

Babe Ruth, the immortal slugger of the New York Yankees, hit 54 home runs that year after hitting 60 the year before – an unheard-of feat. Jack Dempsey, although he had lost the heavyweight boxing crown by then, was still a popular sports figure in New York and elsewhere, having held the title for most of the 1920s. On Wall Street, fortunes were being made daily, as the stock market was running full bore, soaring to new records – this about a year before the Great Crash.

On November 6th, 1928, U.S. President Herbert Hoover, who had spoken that fall of America’s “system of rugged individualism,” would defeat Democrat Alfred E Smith in the U.S. Presidential election, winning his second term. Later that year, in December, NBC would set up a permanent, coast-to-coast radio network and Louis Armstrong would record his “West End Blues.”

Aviation, a new industry, was still testing its wings, so to speak, and the American public was captivated with what it saw. “Wing-walkers,” barnstormers, and flying circuses had become popular sources of aviation entertainment in the mid-1910s and 1920s. But more than any single event, it was Charles Lindbergh’s historic May 1927 non-stop flight across the Atlantic Ocean from Long Island, New York to Paris, France that made Americans aware of the potential of commercial aviation.

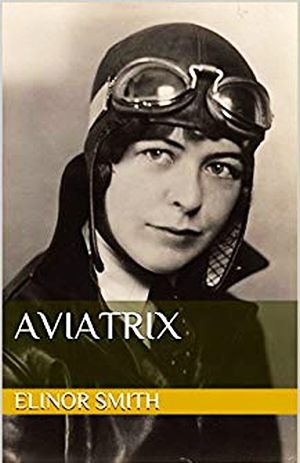

Teenage pilot, Elinor Smith, 1927-28.

Born on August 17, 1911 in New York City, Elinor Smith, at the age of six, took her first flight in a Farman pusher biplane. What she saw that day on her first flight stayed with her forever.

“I could see out over the Atlantic Ocean, I could see the fields, I could even see the [Long Island] Sound,” she recalled. “And the clouds on that particular day had just broken open so there were these shafts of light coming down and lighting up this whole landscape in various greens and yellows.” Young Elinor was hooked: from that point on, all she wanted to do was fly.

Elinor Smith in the cockpit of her plane, circa 1928-29.

Taking lessons as a young girl, she had to have blocks attached to the rudder pedals in order to reach them. Before she was 10, she flew with an instructor, propped up with a pillow and aided by her rudder blocks. By age 12, she would later say, “I could do everything but take off and land.” At 15, she made her first solo flight. Three months later, she set her first of many altitude records – an unofficial women’s light aircraft altitude record of 11,889 feet in a Waco 9 plane. A year later, in 1928, she received her pilot’s certificate, then becoming the youngest pilot at age 16 to receive a license from the Federal Aviation Administration. Orville Wright signed her license.

The 4 Bridges Stunt

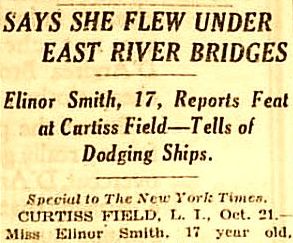

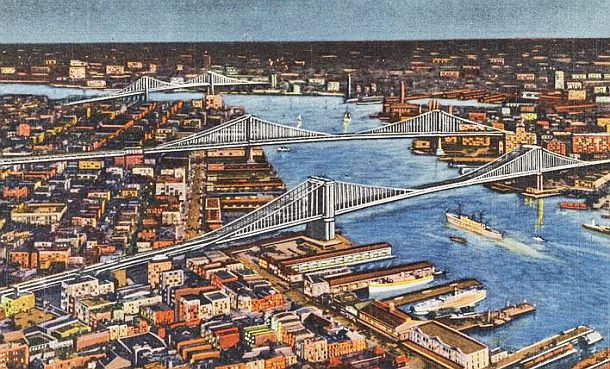

In the fall of 1928, Smith set out to do something that was quite daring. About a month after she received her license, a former barnstorming pilot who hung out at Curtiss Field, bragged to Smith and others about his failed attempt to fly under a bridge. This barnstormer reportedly also spread rumors that Elinor Smith had backed out of trying a similar feat. Other accounts have reported that Smith was ridiculed by male pilots and was acting on a dare to try the feat. So the 17-year-old Smith decided not only to try flying under one bridge, but four – the Queensboro, Williamsburg, Manhattan and Brooklyn bridges – all on New York’s East River.

Artist’s rendition /recreation of Elinor Smith’s plane approaching the Queensboro Bridge for a “below-the-bridge” flying stunt. Adapted from an illustration by Francois Roca in Tami Lewis Brown’s 2010 book, “Soar, Elinor.” Click for book.

Smith undertook her plan with careful preparation. She visited all four locations of the bridges, and studied their structures, suspension features, and pillers. She also noted the surroundings of each bridge, their use, the river tides, and especially the extent and nature of the river traffic below each bridge. Smith had also done some aerial reconnaissance above the East River and the four bridges to plot the route she would fly in approaching the bridges. She had also practiced low-level flying around ship masts on western Long Island’s Manhasset Bay. Still, the feat was daring and filled with risk. There could be unpredictable winds, and ships and boats on the river could move in unpredictable directions. And there was also a big professional risk even if successful: she could lose her pilot’s license for the stunt, regarded as a threat to public safety.

Photograph of Elinor Smith & plane (circled) flying beneath New York city’s Manhattan Bridge on the East River, October 21, 1928. Photo by Nick Petersen/NY Daily News.

In her autobiography, Aviatrix, Smith recalled that she was disappointed that none of the newsmen who had dared her to undertake the feat, had come out to see her off that morning. But Smith had a few well wishers that day, including one who thoroughly surprised her.

As she was seated in her cockpit making preparations for her flight, someone tapped on her shoulder. When she turned around, she would later recount, “I found myself staring into the handsome face of the world’s hero, Charles Lindbergh.” Lindbergh gave her a big smile and said, “Good luck, kid. Keep your nose down in the turns.” Lindbergh’s support and encouragement was just what she needed.

Among the crowd of friends and pilots she had come to know at the Curtiss airfield on Long Island, there had been much talk and some betting about whether she could really accomplish the four-bridges fly under feat she had set for herself. However, those in Elinor’s corner had alerted the media in advance of her plan so there would be clear evidence in the newspapers and on film that she was the person flying the plane should she succeed. Smith herself, however, was unaware that the media and newsreel crews had been alerted to her plan.

(Reportedly there were newsreel crews at each bridge that day, and Cynthia Krieg of the Freeport Historical Society has stated that the library at the University of California, Los Angeles has an archive of old Hearst movie reels and may have the footage of Smith flying under the bridges).

According to one recounting of her flight that appeared in a 2010 Wall Street Journal story: “…[Smith] headed south in her Waco 9 biplane, dodging ships while flying beneath the Queensboro, Williamsburg and Manhattan bridges. She finished by flying sideways beneath the Brooklyn Bridge and then circled the Statue of Liberty twice.” One account of her finish noted that boats in the harbor blew their whistles in salute to the young pilot. The New York Daily News of October 22nd, 1928 — which gave the event front-page coverage with photos — reported: “Elinor Smith, Freeport’s 17-year-old aviatrix, nonchalantly ducked under four East River bridges yesterday afternoon in a Waco biplane and reported the stunt was easy… ‘I had to dodge a couple of ships near the bridges, but there was plenty of room,’ the high school aviatrix reported.”

Headlines from New York Times story , October 22, 1928.

The stunt, in any case, made her an instant celebrity and helped win her the nickname “The Flying Flapper.”

At New York’s city hall several days later, however, the young pilot was called to account for her actions. She received a 10-day “grounding” by the city of New York, the prerogative of then Mayor James J. Walker. However, Walker interceded on the young pilot’s behalf to prevent U. S. Department of Commerce from suspending her license. Other reports indicate there was a 15-day suspension of her license for the stunt.

An artist’s rendering from the 1940s showing three of the four bridges on New York’s East River that Elinor Smith and her plane flew beneath on October 21, 1928. In order, from the top: the Williamsburg Bridge, the Manhattan Bridge, and the Brooklyn Bridge. Not shown and further upriver and the first bridge Smith flew under, was the Queensboro Bridge.

A 1981 photograph showing two of the bridges Elinor Smith flew beneath in 1928 – the Manhattan Bridge and the Brooklyn Bridge – more or less as they appear today.

Poster promoting Elinor Smith as celebrity aviation correspondent for NBC Radio in the early 1930s.

Advertising posters such as the one at right would later tout her radio broadcasts – “Famed Star In The Air, And On The Air,” offered one NBC tagline. Both NBC and CBS wanted her, but NBC gave her a weekly show.

During her career, Smith would also do some writing, becoming aviation editor at Liberty magazine and also writing stories that appeared in Aero Digest, Colliers, Popular Science, and Vanity Fair.

But Smith was a very active aviator in her early years, and she continued to push the bounds for female pilots, setting records on her own and with other female partners.

On January 30th, 1929, flying an open cockpit Bruner Winkle biplane with zero degree temperatures aloft, Smith set a women’s solo endurance record of 13½ hours. Three months later, in April 1929, after other women pilots had broken her endurance record, Smith again took to the skies, staying aloft for 26½ hours in a Bellanca CH monoplane, also marking the first time a woman had piloted such a large and powerful aircraft.

In May 1929, she set a women’s world speed record of 190.8 miles per hour in a Curtiss military aircraft. The following month, the Irving Parachute Company hired her to tour the U.S. and fly a Bellanca Pacemaker on a 6,000-mile tour

A Universal Newsreel title screen featuring a story on one of Elinor Smith’s record flights for altitude. |

Crowd of admirers gathering around Elinor Smith's plane on arrival at airfield after one of her record-setting flights. |

Elinor Smith greeting a well-wisher from the cockpit of her plane, one of the crowd who came out to cheer her return. |

Smith also teamed up with another female flier, Evelyn “Bobbi” Trout. In November 1929, flying out of what is now Van Nuys Airport in Los Angeles, the pair set the first official women’s record for endurance with a mid-air refueling, at 42½ hours.

In March 1930 Elinor surpassed the world altitude record by 1 mile, flying to a height of 27,419 feet. It was following this event, after she had given an interesting interview to an NBC radio reporter, that the 18 year-old Smith was offered a broadcasting position covering aviation. Through 1935 she would do live broadcasts for NBC from air shows such as the Cleveland Air Races. She also did interviews with pilots and covered Graf Zeppelin landings as well.

Among her other distinctions, Elinor Smith also became the youngest pilot ever granted a Transport License by the U.S. Department of Commerce. But one of her most prized honors came in a poll of licensed pilots conducted in October 1930, when she was voted the “Best Woman Pilot in America,” beating out her contemporary, Amelia Earhart.

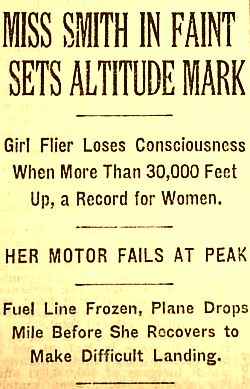

In March 1931, she attempted to set the world altitude record again, but almost met with disaster when she blacked out at high altitude and her plane went into a steep dive.

Fortunately, at about 6,000 feet, Smith regained consciousness and managed to pull out of the dive and bring the plane to a safe but damaging landing, forcing the plane up on its nose purposely to avoid wing damage.

Ten days later, after repairs, she made a second attempt at the record, securing the women’s record again at 32,567 feet, but not the world record. Smith also had hopes of doing a non-stop trans-Atlantic solo flight, but the Great Depression put the damper on that venture.

New York Times story on Elinor Smith’s flight of March 1931 when she blacked out and had engine failure, but still managed to recover from both and set an altitude record.

For a time thereafter, Elinor Smith continued to be a prominent stunt flyer. She also performed for numerous Depression-era fundraisers, some benefiting the homeless and needy.

In 1933, she married New York State legislator and attorney Patrick H. Sullivan. In 1934, Elinor Smith appeared on a Wheaties cereal box (shown at the top of this story), the same year that baseball star Lou Gehrig of the New York Yankees also appeared. He was the first athlete to appear on a Wheaties box, and Elinor the first female.

After the birth of her first two children, she decided to retire from flying and would spend the next 20 years as a suburban housewife, raising her four children. Following her husband’s death in 1956, she returned to flying periodically, including piloting the Lockheed T-33 jet trainer and C-119s for paratroop maneuvers.

In 1981 her autobiography, Aviatrix, was published in New York by Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, and in 2001 she was inducted into the Women in Aviation International Pioneer Hall of Fame.

At age 89, in April 2001, she flew an experimental C33 Raytheon AGATE, Beech Bonanza at Langley Air Force Base in Virginia. A year earlier, in March 2000, with an all-woman crew, she had piloted NASA’s Space Shuttle vertical motion simulator, becoming the oldest pilot to navigate a simulated shuttle landing.

Elinor Smith, portrait photo, circa 1930s.

“Significant Flying”

At the death of Elinor Smith in 2010, age 98, Dorothy Cochrane, a curator at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, told the Washington Post: “She’s not a household word, but she probably should be because she did some really significant flying.”

Today, Elinor Smith is among the female fliers whose photographs and biographies are on display at the Women in Aviation and Space History section of the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C.

Readers of this story may also find “1930s Super Girl” of interest, featuring the athletic career of 1932 Olympics phenom and later golfing sensation, Babe Didrikson. For additional stories on famous and interesting women at this website see, “Noteworthy Ladies,” a topics page with thumbnail links to 36 other stories on a variety of women. Thanks for visiting – and if you like what you see here, please make a donation to support the research and writing at this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

____________________________________

Date Posted: 6 April 2015

Last Update: 26 April 2019

Comments to: jdoyle@pophistorydig.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “The Flying Flapper, 1920-1930s,”

PopHistoryDig.com, April 6, 2015.

____________________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

April 24, 1929: Elinor Smith, 17, waves from the cockpit of her Bellanca CH 300 Pacemaker after setting an endurance record from Roosevelt Field, Long Island, NY. Photo, Newsday |

November 1929: Bobbi Trout (left) and Elinor Smith with their Sunbeam airplane around the time they set a 42½ hour flight endurance record with a refueling. |

Flight of Elinor Smith & Bobbi Trout photographed at 32 hours during refueling in mid-air (light line between planes). Smith did the flying, Trout handled the fuel lines. |

Laura Muha, “Newsday’s 2000 Profile of Elinor Smith Sullivan,” Newsday (Long Island, NY), November 14, 2000.

“Elinor Smith,” Wikipedia.org.

Phyllis R. Moses, “Keep Your Nose Down in the Turns,” Aviation History (WingsAndStars .com), September 2003.

“Elinor Smith,” CradleOfAviation.org.

“Says She Flew Under East River Bridges; Elinor Smith, 17, Reports Feat at Curtiss Field–Tells of Dodging Ships,” New York Times, October 22, 1928. p. 3.

Associated Press (Roosevelt Field, N.Y.), “Flapper ‘Ace’ Tops Women’s Air Records; Elinor Smith Is Up Above 26 Hours; Victor Over Four,” April 24, 1929.

“Miss Smith in Faint Sets Altitude Mark; Girl Flier Loses Consciousness When More Than 30,000 Feet Up, a Record for Women. Her Motor Fails at Peak; Fuel Line Frozen, Plane Drops Mile Before She Recovers to Make Difficult Landing,” New York Times, March 11, 1930. p. 1.

“Elinor Smith Passes Test; Freeport Flier, 18, Qualifies for Transport Pilot’s License,” New York Times, April 6, 1930.

“Elinor Smith Assails Foes of Stunt Flying; Replying to Exchange Club Head at Freeport Luncheon, She Says Aviators Are Business People.” New York Times, September 11, 1930.

“Girl Flier’s Hard Trip; Elinor Smith Uses Planes, Trains, Taxis and Motor Boat to Cross Country in Two Days for Radio Engagement; Decides to Take Chance,” New York Times, December 7, 1930.

Elinor Smith, Aviatrix, New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1981, 304pp.

Phyllis R. Moses, “The Amazing Aviatrix Elinor Smith,” Women Pilot, (Chicago, Illinois), March 30, 2008.

Denise Lineberry, “Elinor Smith: Born to Fly,” The Researcher News/NASA.gov, NASA Langley Research Center, March 30, 2010.

“The Pioneers: Elinor Smith,” Ctie.Monash .edu.

Andrew Hackmack, Local Aviation History, “Famous Female Flyer Talk a Family Affair,” Valley Stream Herald (Nassau County, NY), January 6, 2010.

Stephen Miller, “Elinor Smith 1911-2010: A Barnstormer Who Flew With the Stars,” Wall Street Journal, March 24, 2010 p. A-6.

Patricia Sullivan, “Pioneering Pilot Elinor Smith Sullivan Dies at 98,” Washington Post, Wednesday, March 24, 2010.

“Elinor Smith Sullivan Dies at 98; Daring Female Pilot,” Los Angles Times, March 28, 2010.

Julie Vessigault , “Elinor Smith, Aviatrix of the Golden Age of Aviation, Gone West,” NYCaviation.com, March 29, 2010.

Erica R. Hendry “Saying Goodbye to One of America’s Earliest Female Aviation Pioneers: Elinor Smith Sullivan, Smithsonian.com, March 30, 2010.

Tami Lewis Brown, Soar, Elinor! / Pictures by Francois Roca, New York: Farrar Strauss, October, 2010.

Sally Lodge, “Book on Pioneering Aviatrix Takes Flight” (Review of Soar, Elinor!), Publishers Weekly.com, October 21, 2010.

“Women’s History Month Activity Kit,” Based on the Book, Soar, Elinor!, by Tami Lewis Brown.

“1920’s The Flying Flapper – Elinor Smith,” YouTube.com (6:46), Posted by Aaron1912, April 9, 2010.

Elinor Smith, “Women in Aviation and Space History,” Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum Archives, Washington, DC.

_____________________________