Among the “wonder products” generated by the synthetic chemical revolution of the mid-20th century are an array of plastics that today permeate all manner of products and structures throughout the world. And tragically, as learned in the June 14th, 2017 London Grenfell high-rise fire that claimed 72 lives and injured 70 others, the building’s exterior skin – consisting of aluminum composite panels with a polyethylene core plus polyisocyanurate insulation behind the panels — have been implicated in subsequent reports and investigations as playing a key role in the fire’s rapid spread and severity.

June 2017. Photo of the Grenfell Tower high-rise fire in progress in London, believed to have been aided in its rapid spread by the building’s exterior cladding; panels which incorporated a polyethylene-filled core, and also, possibly, plastic insulation.

And beyond the role the plastic-filled exterior building panels and/or insulation played in the Grenfell Tower blaze, another issue raised in fires of this kind is the toxic gases given off by multiple burning plastic substances – from furniture and carpeting to wall coverings and plastic piping. In fact, “toxic fires” fueled by an array of plastic products remain a serious problem worldwide, and one that was not foreseen at the invention stage of the “miracle plastics.”

1927 headlines for Cleveland Clinic fire; other headlines note “poisonous fumes from burning x-ray films continue to claim victims” – one of the early plastic-fueled fires. |

Headlines for 1942 Cocoanut Grove fire in Boston, where nitrocellulose decor was a later-implicated fuel. |

For decades, little was known about the special toxicity that came with plastics that burn in accidental fires in homes, office buildings, cars and trucks. But over the years, as major fires have occurred in which plastics have been implicated, more has been learned about their toxicity.

Most plastics are carbon-based materials and will burn and give off gases and smoke when subjected to a flame.

Burning polyurethane foam, for example, instantly develops dark smoke along with deadly carbon monoxide and hydrogen cyanide gas. Inhaling this smoke only 2 or 3 times would cause rapid loss of consciousness and eventually, death by internal suffocation.

Yet, sadly, protective regulations, safety standards and building codes to deal with these and other dangers have lagged behind the learning.

The trail of tragedies dates to the earliest uses of plastics, some implicating substances such as nitrocellulose used in celluloid. A 1927 fire at the Cleveland Clinic killed 135 people as an acrid brown-black smoke was generated from the nitrocellulose x-ray film used at the clinic. That fire was among the first to be fueled by synthetics. But it wasn’t the last.

The famous catastrophic 1942 Cocoanut Grove nightclub fire killed more than 400 people. An investigation highlighted some obvious issues in that fire. But only a handful of scientists and investigators knew that the nightclub’s copious decor of nitrocellulose cocoanut fibers was a contributing cause of the resulting death and injury.

By the 1950s and 1960s, a wide array of synthetics began filling up homes and office buildings, such as nylon carpeting, urethane foam mattresses, plastic filled soft furniture. and PVC wire insulation. Automobiles, trucks and planes added synthetics material to their construction and interiors as well.

During the 1960s and 1970s, airplane crashes in which victims survived the crash but died in a toxic fire began to raise questions about the plastic material inside planes. And the 1969 New York Harbor fire aboard the USS Enterprise killed many sailors after plastic-coated electric cables burned.

Following these incidents, a White House report on fire in 1972 — America Burning — noted that plastics were being sold and used without adequate attention to the special fire hazard they presented. But when the National Fire Protection Association tried in 1975 to require by code that material used in construction be no more toxic than wood, the Society of the Plastics Industry blocked the move.

In 1974–75, some plastics manufacturers advertised that urethane foam was fireproof and self extinguishing, a claim the Federal Trade Commission challenged, but only resulted in industry’s “rehabilitating the product” to improve its public image.

‘Dragon Fires’

Deborah Wallace’s 1990 book, “In the Mouth of the Dragon,” details the dangers of plastic-fueled toxic fires. Click for book.

“No one thought to test [the] early synthetic polymers for their combustion toxicity. These products were virtually untested when they were put on the market. Instead, the public became the test animals.”

Wallace describes in detail the “plastics effect” in a number of toxic fires occurring in recent history, among them:

> the 1975 New York Telephone Exchange fire that injured 239 out of 700 firefighters who battled a blaze fueled by polyvinyl chloride (PVC);

[ One later description of that fire from The New York Daily News noted: “…A 16-hour blaze followed in which more than 100 tons of PVC sheathing in a rat’s nest of wires went up in smoke at a phone switching high-rise south of 14th St. on Second Ave. Clouds of hydrochloric acid and fumes of cancer-causing benzene and vinyl chloride filled the air as the conflagration boiled within a sealed vault three stories below ground. At one point, an explosion of accumulated hydrocarbon gas knocked firefighters outside to the pavement. Men inside used up their air cylinders, unable to escape in dense, black smoke without gulping the toxic air….” The Daily News also noted later-reported, PVC-related cancer deaths among Telephone Exchange firefighters.]

> the Beverly Hills Supper Club fire of 1977, in which 165 people were killed in an electrical and PVC-fueled blaze;

> the 1978 Cambridge, Ohio Holiday Inn fire in which 10 died from smoke from burning PVC and nylon;

> the 1978 Younkers Brothers Department Store fire in which 10 people died in another PVC-electrical fire;

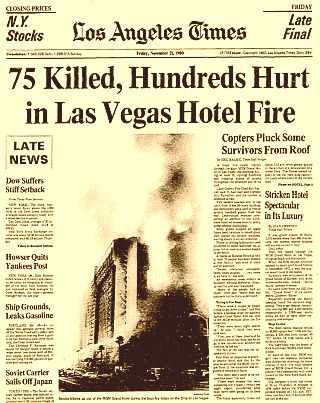

> the 1980 MGM Grand Hotel fire in which 85 died and 600 were injured in a fire largely fueled by plastics;

> the 1980 Stouffer’s Inn fire in which 26 people died in a blaze fueled by PVC and nylon/wool;

> the 1983 Westgate Hilton fire in which 12 died from smoke that came mainly from PVC and urethane foam; and,

> the 1983 Fort Worth Ramada Inn fire in which five died from PVC and nylon fumes.

Early L. A. Times headlines on the November 1980 MGM Hotel fire that would finally take 85 lives, with plastics heavily implicated.

Although The Station nightclub fire was caused by pyrotechnics set off as part of the Great White rock band’s act that night, the fire’s spread and intensity were aided by ignited plastic foam used as sound insulation in the walls and ceilings surrounding the stage, materials that generated considerable carbon monoxide and hydrogen cyanide within a few minutes.

Plastic material was implicated in the September 23, 2007 fire at the Water Club Tower at the Borgata Casino Hotel in Atlantic City, New Jersey where fire raced up 38 stories on the face of the building. And since 2012, fires fueled by metal composite cladding with plastic cores have occurred in high-rise buildings in France, Dubai, and South Korea. Thousands of structures worldwide may be similarly vulnerable.

Fires at plastic manufacturing facilities and in storage areas can also yield catastrophic results. In March 2017, spools of high density polyethylene (HDPE) conduit stored below a freeway in Atlanta, Georgia fueled an intense fire there that caused an elevated portion of I-85 to collapse on March 30th. In the spectacular blaze, flames shot 40 feet into the air, and the heat was so intense that it melted supporting metal structures. Both directions of I-85 were closed in a key area of Atlanta near its busy downtown hub.

Meanwhile, individual homes continue to be vulnerable to the toxic effects of plastic-fueled fires, as everything from urethane-filled sofas and mattresses to PVC siding, wall coverings, plumbing lines, and molded furniture can provide toxic fuel.

Grenfell Update: In addition to the suspected role that the polyethylene-filled exterior cladding panels may have played in the June 2017 Grenfell Tower fire, an insulation foam product named Celotex RS5000, a polyisocyanurate product, was also used in that building, installed behind the cladding. Some have stated that this insulation was more flammable than the cladding.

Grenfell Tower fire near its end, with bits and fragments of exterior cladding and insulation seen in the charred remains.

Building and fire codes in recent years have no doubt been updated in many jurisdictions to take account of the toxic effects of plastic materials, leading to safer installations and products. But certainly not everywhere, as the Grenfell tragedy attests. Given the ubiquity of plastics in modern use, plastic-fueled infernos are likely to remain a danger throughout the world.

And beyond the fire dangers of modern plastics, there are a whole host of other problems associated with this miracle of inventive science – not least those being, for example: plastics in municipal waste incineration, in landfills, worker exposures in “upstream” chemical manufacturing, plastic chemicals leaching from food packaging and containers, the tons of plastics floating in the world’s oceans, and plastic chemicals and their breakdown products found in human blood and body tissue.

See also at this website, the “Environmental History” topics page which offers additional stories on spills, fires, and explosions in the oil industry; agricultural pesticide history; and surface coal mining in Ohio and Kentucky. Thanks for visiting – and if you find the reporting and story development at this website useful and informative, please make a donation to help support its continued publication. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

____________________________________

Date Posted: 5 July 2017

Last Update: 12 August 2021

Comments to: jackdoyle47@gmail.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Plastic Infernos: A Short History,”

PopHistoryDig.com, July 5, 2017.

____________________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

“London Fire: What We Know So Far About Grenfell Tower” and, “London Fire: Six Questions for the Investigation,” BBC News, June 23, 2017.

“Grenfell Tower Fire,” Wikipedia.org.

Robert Moulton, “The Cocoanut Grove Night Club Fire, Boston, November 28, 1942,” National Fire Protection Association, 1943.

D.L. Breting, Underwriters Laboratories, “Pretty Plastics–Ugly Fires,” 1954.

J. Harry DuBois, Plastics History U.S.A, 1972.

Ronald K Jurgen (Editor), “The Great New York Telephone Fire,” IEEE Spectrum Magazine, Vol. 12, No. 6, June, 1975.

Richard Best, Investigation Report on The MGM Grand Hotel Fire, Las Vegas, Nevada, November 21, 1980, National Fire Protection Association, Report revised January 15, 1982.

Deborah Wallace, In the Mouth of the Dragon: Toxic Fires in the Age of Plastics, Avery Publishing Group, Garden City Park, New York, 1990.

Stephen Fenichell, Plastic: The Making of A Synthetic Century, Harper- Collins: New York, 1996.

Robert Burke, “Plastics & Polymerization: What Firefighters Need To Know,” Firehouse, February 28, 1999.

Bob Port, “Three Decades After an Infamous New York Telephone Co. Blaze, Cancer Ravages Heroes,” New York Daily News, Sunday, March 14, 2004.

James M. Foley, “Modern Building Materials Are Factors in Atlantic City Fires,” Fire Engineering, May 1, 2010.

Susan Freinkel, Plastic: A Toxic Love Story, April 2011.

Thunderthief, “PSA–Burning Plastic Can Kill You,” DailyKos.com, June 2, 2012.

Associated Press, “Fire That Killed Newark Family Fueled by Plastic Flowers,” New York Post, June 17, 2014.

Carla Williams, “Smoked Out: Are Firefighters in More Danger than Ever Before? New Construction Materials Are Making Firefighting More Hazardous to the Health and Well Being of First Responders, As Well as Building Tenants and Homeowners,” EHSToday.com, September 7, 2016.

Catherine Kavanaugh, “Plastic Conduit Fuels Fire That Brings Down I-85 Overpass,” PlasticsNews.com, March 31, 2017.

Justin Pritchard, Associated Press, “Insulating Skin on High-Rises Has Fueled Fires Before London,” ABC News.com, June 18, 2017.

“Grenfell Tower Fire” (Polyisocyanurate insulation), Wikipedia.org.

_________________________