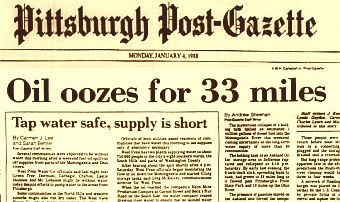

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette of January 4th, 1988, describes river pollution from Ashland oil tank failure & drinking water concerns.

The Monongahela River flows north-northwest to Pittsburgh, where it joins the Allegheny River to form the Ohio River, then flowing west and southwest into the West Virginia panhandle, Ohio, and beyond. The spill’s pollution of the Monongahela and Ohio rivers created an acute public safety emergency. Public water systems were shuttered and more than one million people in some 80 communities downstream in Pennsylvania, Ohio, and West Virginia were affected. Some towns were without regular water services for up to eight days. Thousands of birds and fish were killed.

Artists’ rendering of failed storage tank at Ashland Oil Co.’s Floreffe, PA complex in January 1988. Source: EPA. |

Aerial photo looking down on the scene with twisted shell of split tank remaining and “dented” neighboring tank at right. |

The Monongahela River flows north to Pittsburgh where it joins the Allegheny, then forming the Ohio River. Floreffe, where the tank burst, is about 25 miles south of Pittsburgh. |

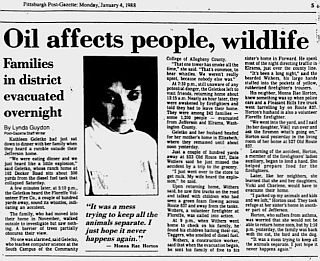

January 4, 1988: The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette reported on the evacuation of some 242 families near the spill site. |

The tank’s failure occurred while it was being filled to capacity for the first time after it had been installed at Ashland’s Floreffe storage yard. The big tank, which had been previously used in Ohio, was dismantled there and moved to Pennsylvania where it was reassembled. When the tank split apart, its contents overwhelmed the standard earthen containment dikes, as millions of gallons of diesel fuel swamped and flooded the storage complex and flowed across adjacent property, reaching a nearby drain. About 775,000 gallons of the spilled fuel entered the Monongahela River through the drain.

The force generated at the site by the escaping fuel volume as it burst from the tank was considerable. Some local residents reported hearing a low level explosion-like sound as the tank split apart. The escaping oil from the big tank actually propelled it backwards off of its foundation, ripping and bending the structure. The steel shell of the tank itself was left “twisted and contorted” on the ground, as the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) would later report.

“[M]assive steel columns and other internal support members were bent into acute angles and thrown dozens of feet from their original locations,” DEP would explain in one report. “The shell itself was displaced about 120 feet to the east of its original location.”

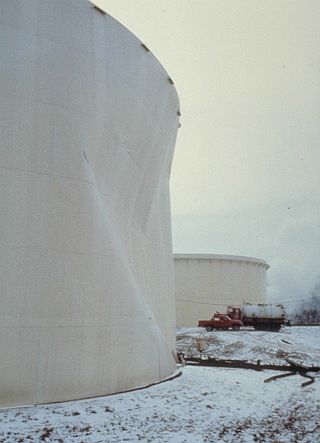

Another large storage tank, about one hundred feet away, was crumpled at its side by the impact of the surging fuel from the burst tank. A second nearby tank exhibited brownish stains all the way up its side – some forty feet from ground level – where the escaping fuel had splashed against it. One small structure also in the path of the spill, was swept away.

On the first night following the spill, some 242 families – about 1,200 people – were evacuated from their homes in Jefferson and Elrama in Washington County near the Ashland facility. Firefighters from the Floreffe Volunteer Fire Co., had begun going door-to-door in the area telling people they had to leave their homes as a precaution for safety reasons.

During the tank collapse, some debris from the spill had punctured a gasoline line at another big million-gallon tank, which had then leaked some 20,000 gallons of gasoline. A mixture of diesel and gasoline fumes can create a danger of an explosion, which was the primary reason for the evacuation. Lt. Gov. Mark S. Singel visited evacuees the day in a shelter set up at a local high school.

By Monday evening, January 4th, 1988, the Pittsburgh oil spill was among the top stories on the NBC Evening News with Tom Brokaw. The network’s Cassandra Clayton reported from the Monongahela River showing emergency crews at work with attempted clean-up efforts and also noting that Pennsylvania Governor Robert P. Casey had declared the region a disaster area. Some local residents appeared on camera expressing concern about drinking water safety, and Pittsburgh’s public safety director, Glenn Cannon, commented that cleanup costs would be substantial.

On the Monongahela, meanwhile, a giant oil slick soon moved down river, washing over two dam locks and dispersing throughout the width and depth of the river. The spill not only killed birds and fish and contaminated drinking water, but also damaged private property and adversely impacted area businesses. The Coast Guard closed the Monongahela River to vessel traffic between the Ashland facility in West Elizabeth and Pittsburgh. The smell of diesel fuel could be detected as far north as Pittsburgh. Rail and motor vehicle traffic was halted along some routes near the river due to concerns about human health and fire hazards.

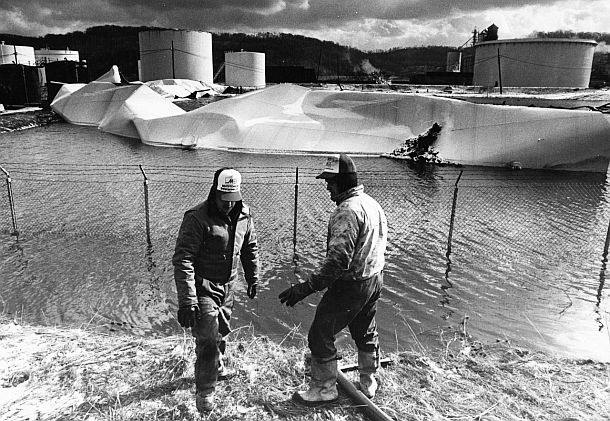

January 1988: Workers at Ashland’s Floreffe, PA storage yard in aftermath of tank collapse, try to clean up some remains of spilled diesel fuel in an earthen-bermed containment area. Photo, Darrell Sapp/Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

As the diesel fuel entered the Monongahela River above Pittsburgh, at least five municipal water suppliers serving tens of thousands of residents were affected, closing their water intakes. Water conservation measures were put in place to conserve supplies; classes in some Pittsburgh schools were suspended, for example, to help conserve water. Still, some Pittsburgh residents went without normal water service from January 4 until January 12th.

When the oil slick reached the junction of the Monongahela and Allegheny rivers – which together form the Ohio River which continues west and southwest – concentrations of diesel fuel remained high enough to warrant continuing concern for downriver users in the states of West Virginia and Ohio. In Steubenville, Ohio, for example, all nonessential businesses were closed with water service interrupted for three days.

January 1988: Boat on the Monongahela River in the aftermath of the Ashland Oil tank collapse. The “dark patches” in this case are those of water, the rest is spill. Photo, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

By January 8, 1988, although icy water and stiff winds had slowed the flow of the slick, it reached Wheeling, West Virginia. In the days thereafter, it would continue flowing south-southwest down the Ohio River – though in more diluted form – to other large cities, including Louisville, Kentucky, Cincinnati, Ohio, and Evansville, Indiana

In Pennsylvania, meanwhile, at least 11,000 fish and 2,000 birds were killed by the spill, with dozens of miles of river shoreline contaminated. One report later stated that “ millions of fish” were killed. Coast Guard and oil company clean-up of the spilled diesel fuel was hampered by the wintry weather, though some 2.98 million gallons were reported recovered. Still, estimates of between 510,000 gallons and 860,000 gallons of the diesel fuel was not recovered, remaining in the rivers.

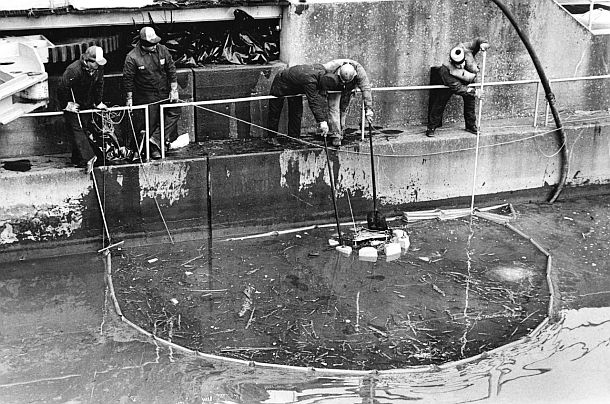

January 1988: Following the Ashland Oil tank collapse, which polluted the Monongahela and Ohio rivers, workers on the Monongahela at the Braddock Lock, attempt to remove oil from the river. Tony Tye/ Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

In September 1988, Ashland was indicted by a federal grand jury for negligently discharging oil into the Monongahela River in violation of the Clean Water Act. Ashland faced $32.5 million in assorted fines and settlements, including: $14 million for damages, expenses, and civil penalties (including $4.6 million in costs and civil penalties to the state of Pennsylvania); $11 million for cleanup; $5.25 million in attorneys’ fees; and $2.25 million for a Federal criminal fine for negligence in the spill. The Ashland spill, according to Mary Ellen Bolish of the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Resources, speaking at the time of the incident, “could have been prevented if the tank had been inspected.” She added that the Ashland tank failure was “the huge one,” but that smaller such incidents were then occurring “all over the state.”

Nearby tank damaged by the force of escaping oil from collapsed tank at Ashland’s Floreffe complex. Photo, NOAA.

Lack of Regulation

The Ashland tank collapse highlighted the inadequate regulation of aboveground storage tanks – known as “ASTs” – at both the state and federal levels. According to EPA at that time, only 15 states had laws then regulating ASTs. Less than half of the states even bothered to keep track of AST spills. Thirty-four states then regulated ASTs under National Fire Protection Association standards – standards that had little to do with protecting the environment, rivers and streams, or groundwater. Among states that did regulate, the jurisdictions and authorities were unclear, sometimes spread over several agencies. Local jurisdictions were often left fending for themselves, or at the very least, confused about who to call for help when a large spill or underground leak threatened a school, a water supply, or residential areas.

A brief round of Congressional inquiries into ASTs followed the Ashland incident, and a number of bills were introduced, ranging from those designed to prevent catastrophic spills like Ashland’s, to others that would subject ASTs to tougher licensing and inspection procedures. But the central regulatory failing that surfaced in the various post mortems of the Ashland spill was the lack of government-mandated standards for tank design, construction, operation and inspection — a series of changes, which if adopted and enforced, would shift the federal emphasis from after-the-fact spill clean-up and contingency planning to spill prevention.

“EPA’s regulations do not require that operators of oil storage facilities construct and test tanks using industry standards,” reported a 1989 General Accounting Office (GAO) study to Congress. “The Ashland tank was not constructed of materials meeting current industry standards and was not tested for integrity as required by these standards. The tank ripped apart when it was first filled to capacity. Subsequent metallurgical analysis showed that it was not tough enough for the cold temperatures and stress to which it was subjected.”

Another shot of the Ashland terminal in relation to the Monongahela River at right, following the tank collapse.

Underground Leaks

Aboveground tank failures such as the Ashland disaster are rare. However, another major problem with giant oil storage tanks – though mostly out of sight but often more damaging – has been tank leakage, groundwater pollution, and offsite public safety concerns. Such leakage has come from storage tanks at refineries, tank farms, loading terminals and other locations. During the middle and late decades of 20th century in the U.S. and elsewhere, numerous such leaks began to be discovered, some revealing gigantic underground “lakes” or “plumes” of petroleum pollution. Crude oil, gasoline, diesel, jet fuel, and other petroleum and/or petrochemical mixtures, were often found below ground, in varying thicknesses, floating on top of groundwater, or leaking into nearby creeks and streams.

|

“The Daily Damage” This article is one in an occasional series of stories at this website that feature the ongoing environmental and societal impacts of industrial spills, toxic releases, fires, air & water pollution incidents and other such occurrences. These stories will cover both recent incidents and those from history that have left a mark either nationally or locally; have generated controversy, political activity, or government inquiry; and generally have taken a toll on the environment, worker health & safety, and/or local communities. My purpose for including such stories here is simply to drive home the continuing and chronic nature of these incidents through history, and hopefully contribute to public education about them so that improvements will be made in law, regulation, and industry practice, yielding safer alternatives ahead. — Jack Doyle |

Some of these leaks – also occurring on a smaller scale at gasoline stations and smaller storage yards – created public health concerns and /or explosion fears, especially where leaked petroleum product migrated into underground drinking water sources and/or beneath neighboring residential areas.

The 1988 Ashland tank collapse, in any case, is one in a long list of oil industry incidents and accidents imposed on society during many years of extraction, refining, and transporting fossil fuels. Such incidents, and their aftermath, are still apparent, or have left their mark, on many U.S. communities. And for Pittsburgh, the 1988 incident would not be the last time the city would see oil or chemical pollution of its waterways. In March 1990, a Buckeye Pipe Line Co. 10-inch pipeline ruptured after a landslide at Murphy’s Bottom in South Buffalo Township of Armstrong County, sending more than 75,000 gallons of gasoline, kerosene and diesel into the Allegheny River. In February and March of 2010, there were also two smaller spills at the Floreffe tank farm, by then owned by Marathon Petroleum – one of 660 gallons of hydrochloric acid, and another of a oil-based asphalt emulsion of more than 4,000 gallons.

See also at this website “Oil Fouls Montana,” a story about a January 2015 oil pipeline leak in Eastern Montana that polluted the Yellowstone River and disrupted local water supplies; “Burning Philadelphia,” an account of a Gulf Oil Co. refinery explosion and fire in 1975 that killed 8 firefighters and threatened the city; and “Offshore Oil Blaze,” the story of a 1970-71 Gulf of Mexico offshore oil blowout and fire at a Shell Oil platform that killed four workers, injured 37 others, and burned for more than four months. Other stories at this website with environmental-related history include “Burn On, Big River,” about the historic pollution of the Cuyahoga River in Ohio, and “Paradise,” a story about strip mining in Kentucky. For Pittsburgh fans, see “The Mazeroski Moment” (1960 World Series) and “$2.8 Million Baseball Card” (Honus Wagner history). Thanks for visiting – and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research and writing at this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

____________________________________

Date Posted: 6 April 2015

Last Update: 6 December 2017

Comments to: jdoyle@pophistorydig.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Disaster at Pittsburgh – 1988 Oil Tank Collapse,”

PopHistoryDig.com, April 6, 2015.

____________________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

United Press International (UPI), “Oil Spill Endangers Water for Thousands,” January 3, 1988.

Associated Press (AP), “Oil Spill Fouls River, Threatens Water for 750,000,” January 3, 1988.

“1,200 Flee After Spill on River,” Seattle Times (Seattle, WA), January 3, 1988. p.A2.

Andrew Sheehan, “Oil Oozes For 33 Miles,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, January 4, 1988, p. 1.

“Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania Oil Spill,” NBC Evening News, Monday, January 4, 1988 (Tom Brokaw anchor, Cassandra Clayton, reporting, Pittsburgh, PA).

Carman J. Lee and Sarah Behrer, “Tap Water Safe, Supply is Short,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, January 4, 1988, p. 1.

Lynda, Guydon, “Oil Affects People, Wildlife; Families in District Evacuated Overnight, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, January 4, 1988, p. 5.

Wolfgang Saxon, “Monongahela Oil Spill Threatens Water Supplies in Pittsburgh Area,” New York Times, January 5, 1988.

“Oil Spill Cuts Water Supply to Thousands West of Pittsburgh,” Seattle Post-Intel- ligencer, January 5, 1988, p.A-1.

“More Towns Prepare as Diesel-Fuel Spill Moves Downstream,” Seattle Times, January 7, 1988. p.A-2.

“Oil Imperils Water in Two More States,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, January 7, 1988, p. A-3.

Associated Press, “Oil Slick From Tank Collapse Reaches City in West Virginia,” New York Times, January 8, 1988.

John Hartsock, States News Service, “Focus On: The Oil Spill Ashland Oil Co. Tank Collapsed Through Hole In Federal Regulations,” The Morning Call (Allentown, PA), January 10, 1988.

“Diesel Oil Slick Reaches Wheeling, W.Va.; Citizens Urged to Conserve Water,” Seattle Times, January 10, 1988, p. A-2.

“Oil Slick Threatens More Cities Along Pathway of Disaster,” Seattle Times, January 13, 1988. p. B-6.

“Oil Spill Will Disperse in Next 2 Weeks, Experts Says,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, January 13, 1988, p. A-4.

“The Nation : Cincinnati Shuts River Valves as Oil Hits,” Los Angles Times, January 25, 1988

Associated Press, “Bad Welds Detected A Year Before Tank Collapsed,” January, 28, 1988.

U.S. House of Representatives, Committee on Energy and Commerce. Subcommittee on Transportation and Hazardous Materials, Hearing, “Ashland Oil Spill,” 100th Congress, 1st Session, January 26, 1988.

David Guo, “Fisher: Ashland ‘Stonewalling;’ Executive Fails to Answer Queries of [Pennsylvania] Senate Panel,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, February 13, 1988, p. 4.

U.S. Senate, Committee on Environment and Public Works, Subcommittee on Environ- mental Protection,” Hearing, “Oil Spill on Monongahela River,” 100th Congress, 1st Session, February 1988.

Fred J. Sissine, “Oil Storage Tanks: Construction and Testing Issues Arising from the Ashland Oil Spill,” Issue Brief, Science Policy Research Division, Congressional Research Service, Washington, D.C., Updated February 10, 1988, 14pp.

Staff Memorandum (Patty Power) to U.S. Senator John Heinz (R-PA), “Federal Reaction to The Ashland Spill,” February 12, 1988, 3pp.

Tank Collapse Task Force, “Report of the Investigation into the Collapse of Tank 1338,” Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Resources, June 1988.

David Guao, “Substandard Steel At Fault; Report Lists Reasons For Ashland Oil Tank Collapse,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, June 18, 1988, p. 5.

“Ashland 1988: Storage Tank Collapse Sends 500,000 Gallons Of Diesel Fuel into Monongahela River,” Pennsylvania Depart- ment of Environmental Protection.

Associated Press, “Ashland Accepts Oil Spill Accord,” New York Times, November 9, 1989, p. A-32.

Associated Press, “Company To Pay Millions For Spill,” New York Times, November 23, 1989, p. A-22.

ABB Environmental Services, Inc. (EPA-Commissioned study), 1992.

Mike Ward and Scott W. Wright, “Tank Farm Leaks, Spills Increasing Nationwide,” Austin American-Statesman (Austin, TX), Sunday, June 7, 1992, p. A-11.

U.S. General Accounting Office, Report to the Honorable Arlen Specter, U.S. Senate, Inland Oil Spills: Stronger Regulation and Enforcement Needed to Avoid Future Incidents, GAO/RCED-89-65, February 1989, p. 3.

Cdr. E. A. Miklaucic, U.S. Coast Guard, Pittsburgh, PA, and J. Saseen, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Wheeling, WV, “The Ashland Oil Spill, Floreffe, PA – Case History and Response Evaluation,” International Oil Spill Conference, 1989.

Lois N. Epstein, P.E., “Comments Of The Environmental Defense Fund On Oil Pollution Prevention: Non-Transportation-Related Onshore and Offshore Facilities” (Spill Prevention, Control, and Countermeasure Plans), December 23, 1991, Docket Number SPCC-1P., pp. 2-3.

Michael J. Davis, Unregulated Potential Sources of Groundwater Contamination Involving the Transport and Storage of Liquid Fuels: Technical and Policy Issues, Environmental Assessment Programs, Environmental Assessment & Information Sciences Division, Argonne National Laboratory, Argonne, IL (U.S. Department of Energy, Asst. Secretary for Environment, Safety & Health, Office of Environmental Analysis), August 1989.

“Ashland Oil Tank Failure, Floreffe, Pennsylvania, January 1988 (photographs), NOAA Incidents Gallery.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, The Ohio River Oil Spill: A Case Study.

Mila Sanina, “1988: Monongahela Oil Spill,” The Digs (photos from the Pittsburgh Post Gazette)

“Ashland Oil Spill Disaster,” Disasters Channel, YouTube.com, May 25, 2014, (run time, 7:13).

Don Hopey, “Another Leak Reported at Floreffe Tank Farm,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, March 23, 2010.

Jack Doyle, Crude Awakening: The Oil Mess in America, Washington, DC: Friends of the Earth, 1994, 257pp., plus appendices.

Dr. Jeanette M. Trauth, et. al., “Economic and Policy Implications of the January 1988 Ashland Oil Tank Collapse in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania,” Final Report for the Allegheny County Planning Department, University Center for Social and Urban Research, University of Pittsburgh, July 1989, 135pp.

“1988 Tank Collapse Led to Changes in Pa. Law,” The State Journal (Charleston, WV), February 13, 2014.

__________________________