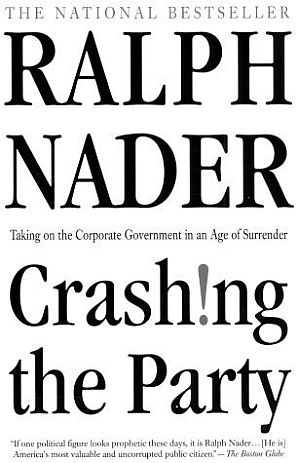

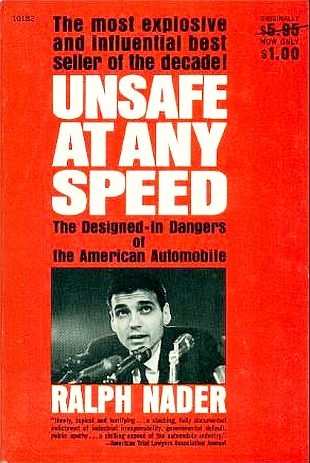

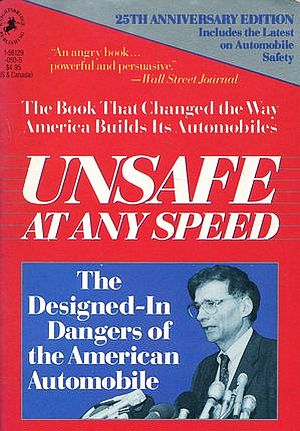

1966 paperback version of Ralph Nader’s “Unsafe at Any Speed” by Pocket Books (hardback published earlier in November 1965 by Grossman Publishers, see cover below). Click for copy.

Nader’s book, a broad investigation of auto safety failings generally, was critical of both the auto industry and the federal government. But one chapter in particular – the first chapter – focused on a compact car named the Corvair produced by GM’s Chevrolet division. Nader titled the chapter, “The Sporty Corvair: The One-Car Accident.” People were being killed and maimed in Corvair accidents that didn’t involve any other cars. The Corvair, it turned out, had some particularly dangerous “designed-in” features that made the car prone to spins and rollovers under certain circumstances.

Initially, Nader and his book were featured at one U.S. Senate hearing in early 1966. But a furor erupted shortly thereafter when it was learned that General Motors had hired private investigators to try to find dirt on Nader to discredit him as a Congressional witness.

Unsafe at Any Speed and Ralph Nader would go on to national fame – the book becoming a best-seller and its author, a national leader in consumer and environmental affairs. But the controversy that first swirled around Nader and the book in the mid-1960s would help spark changes in Washington’s political culture, investigative journalism, and the consumer protection movement that would reverberate to the present day. Some of that history is highlighted below, beginning with background on the man who set all of this in motion.

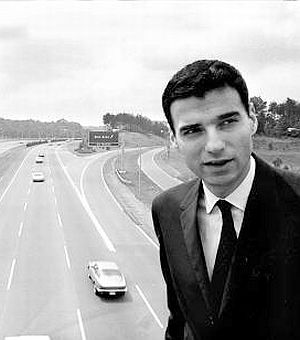

Young Ralph Nader.

Ralph Nader was born in Winsted, Connecticut in 1934 to immigrant parents from Lebanon. Nader credits his parents with instilling the basic values and inquisitiveness that sent him on his way. He graduated from Princeton University in 1955 and Harvard Law School in 1958.

At Harvard, Nader had written articles for the Harvard Law Record, the student run newspaper at the law school. He had also become quite excited on discovering the arguments put forward in a 1956 Harvard Law Review article written by Harold Katz that suggested automobile manufacturers could be liable for unsafe auto design. In his final year at Harvard Law, Nader wrote a paper for one of his courses titled “Automotive Safety Design and Legal Liability.” In his travels around the country as a young man, often hitchhiking, Nader had also seen a share of auto accidents, one of which stayed with him into law school, as former Nader associate Sheila Harty has noted:

“… He remembered one in particular in which a child was decapitated from sitting in the front seat of a car during a collision at only 15 miles per hour. The glove compartment door came open on impact and severed the child at the neck. The cause of the injury—not the accident—was clearly a design problem: where the glove compartment was placed and how lethally thin [the compartment door was] and how insecure the latch.

When studying liability later at Harvard Law School, Nader remembered that accident scene. He posed an alternative answer to the standard determination of which driver was at fault. Nader accused the car…”

Auto accident 1956. Ralph Nader argued that passengers suffered fatalities and injuries needlessly due to poor auto design and lack of safety features.

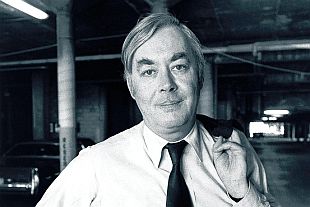

Daniel Patrick Moynihan, shown here in 1976, hired Ralph Nader as a Labor Dept. consultant in 1964.

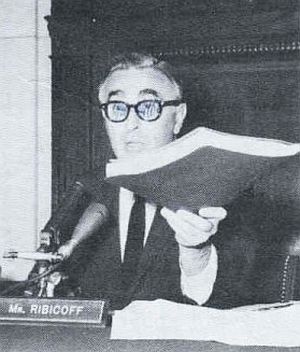

Sen. Abraham Ribicoff, 1960s.

In the U.S. Senate, meanwhile, Senator Abraham Ribicoff (D-CT), the former Governor of Connecticut (1955-1961), had begun a year-long series of hearings on the federal government’s role in traffic safety. Ribicoff was chairman of the Senate Government Operations Committee’s Subcommittee on Executive Reorganization, and his hearings had begun a year earlier, in March 1965. The hearings would continue for another year, yielding nearly 1,600 pages of testimony. In the process, Ribicoff’s committee staff had discovered that Nader was particularly well informed on auto safety issues, and invited him to serve as an unpaid advisor to help the subcommittee prepare for its hearings.

By May of 1965, Nader left the Department of Labor to work full time on the book that would become Unsafe at Any Speed. With his book, Nader would be asking a basic question: why were thousands of Americans being killed and injured in car accidents when technology already existed that could make cars safer?

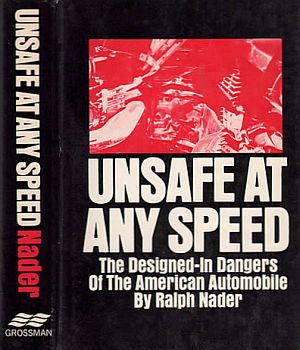

November 1965: Cover & spine of 1st edition hardback copy of Ralph Nader’s “Unsafe at Any Speed,” published by Grossman Publishers, New York, NY. Click for hardback edition.

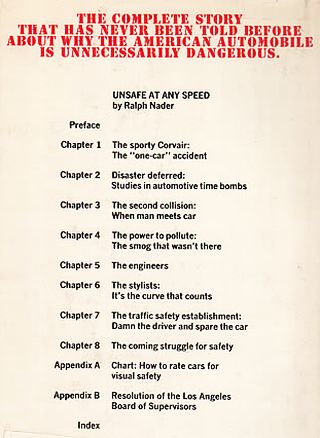

On November 30, 1965, Ralph Nader’s name appeared in a New York Times story the day Unsafe at Any Speed, was published. The hardback edition by Grossman was 305 pages long and had a photo of a mangled auto wreck on its cover. On the back cover, the book’s chapters were listed accompanied by a red-ink headline that stated: “The Complete Story That Has Never Been Told Before About Why The American Automobile Is Unnecessarily Dangerous.”

In the New York Times article on the book’s release, which ran in the back pages of the paper, Nader criticized the auto industry, tire manufacturers, the National Safety Council and the American Automobile Association for ignoring auto safety problems.

The second paragraph of the Times story read: “Ralph Nader, a Washington lawyer, says that auto safety takes a back seat to styling, comfort, speed, power and the desire of auto makers to cut costs.” Nader also charged that the President’s Committee for Traffic Safety was “little more than a private-interest group running a public agency that speaks with the authority of the President.”

Hardback edition back panel, “Unsafe at Any Speed.”

In early 1966, in his State of the Union address, President Lyndon B. Johnson called for the enactment of a National Highway Safety Act. Nader at the time was doing some work at the state level, and had convinced an old friend, Lawrence Scalise, who had become Iowa’s Attorney General, to schedule some auto safety hearings in Iowa.

In Washington, meanwhile, by January 14, 1966 news organizations were reporting that Senator Ribbicoff’s auto safety hearings – the series of hearings begun the previous years – would resume in February.

With Unsafe at Any Speed still in the news, Senator Ribicoff summoned Nader to testify during hearings scheduled for February 10, 1966. Ribbicoff had noted that Unsafe at Any Speed was a “provocative book” that had “some very serious things to say about the design and manufacture of motor vehicles.” The book also raised public policy questions, and was being widely read in the auto industry. At the hearing, Nader lived up to this advance billing, as he provided a scathing description of the auto industry and auto safety establishment.

Ralph Nader testifying at U.S. Senate hearing, 1966.

At the time Nader wrote his book, more than 100 lawsuits had been filed against GM’s Chevrolet division for the Corvair’s alleged deficiencies. Nader had based much of his scathing account of the Corvair’s problems on these legal cases – though he himself was not involved in any of this litigation. GM became very concerned about Nader’s use of this information and worried that more lawsuits would result in the future. The company’s legal department was at the center of this concern, though others in the company were also annoyed by Nader’s book and his activities on Capitol Hill.

GM “Tailing” Nader

Part of GM’s office complex, Detroit, MI, circa 1960s.

The assignment, as Guillen would explain in a letter to his agents, was to investigate Nader’s life and current activities, “to determine what makes him tick,” examining “his real interest in safety, his supporters if any, his politics, his marital status, his friends, his women, boys, etc., drinking, dope, jobs, in fact all facets of his life.”

None of this skullduggery had surfaced publicly, of course – at least not initially – although Nader himself suspected something was going on as early as January 1966. Gillen and agents made contact with almost 60 of Nader’s friends and relatives under the pretense they were doing a “routine pre-employment investigation.” Their questions about Nader probed his personal affairs, and also questioned why a 32-year-old man was still unmarried. Nader would also recount two suspicious attempts in which young ladies made advances toward him – one at a drug store newsstand invited him to her apartment to talk about foreign relations and another sought his help in moving furniture – invitations which Nader declined. Claire Nader, his sister would later report that their mother was getting phone calls a 3 a.m with messages that said: “Tell your son to shove off.”

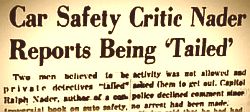

First story of Ralph Nader being followed by private investigators appeared in the Washington Post, February 13, 1966.

GM’s use of private detectives to follow Ralph Nader became a national news story in March 1966.

When details of GM’s investigation of Nader became public, Senator Ribicoff and others on Capitol Hill were outraged. Ribicoff, for one, announced that his subcommittee would hold hearings into the incident and that he expected “a public explanation of the alleged harassment of a Senate Committee witness…” “Anonymous phone calls in the middle of the night have no place in a free society.”

– Sen. Abraham Ribicoff, 1966 Ribicoff and Senator Gaylord Nelson from Wisconsin also called for a Justice Department investigation into the harassment. “No citizen of this country should be focused to endure the kind of clumsy harassment to which Mr. Nader has apparently been subjected since the publication of his book,” said Ribicoff. “Anonymous phone calls in the middle of the night have no place in a free society.” Senator Gaylord Nelson had also made remarks about GM’s investigation of Nader: “This raises grave and serious questions of national significance. What are we coming to when a great and powerful corporation will engage in such unethical and scandalous activity in an effort to discredit a citizen who is a witness before a Congressional committee. If great corporations can engage in this kind of intimidation, it is an assault upon freedom in America.” Ribicoff, meanwhile, had summoned the president of General Motors to appear at the hearings, making for a dramatic showdown in the U.S. Senate.

U.S. Senators taking their places for the 1966 hearing. |

A portion of the crowd attending GM hearing, 1966. |

Senators Ribicoff, Harris & Kennedy during the hearing. |

Ted Sorensen, left, with GM CEO James Roche. |

Senator Kennedy during questioning of James Roche. |

Ralph Nader sat in the first row of the audience during the hearing and also testified. |

GM’s general counsel, Aloysius Power, admitted to ordering the spying on Nader. Eileen Murphy, right, directed the operation. Asst counsel, L. Bridenstine, left. |

Holding the GM report on Nader, Senator Ribicoff at one point, upset with GM’s campaign to “smear a man,” reportedly said to GM witnesses, “...and you didn’t find a damn thing,” tossing the report on the table. |

Ralph Nader addressing the Ribicoff Committee during the March 1966 Senate hearing. |

On The Hill

Senate Showdown

On March 22, 1966, the hearing was set in a large U.S. Senate committee room. Television cameras were set up and a throng of print reporters had come out for the hearing. An overflow audience also packed the hearing room to standing room only. In addition to Senator Ribicoff, chairing the proceedings, others Senators had also come to ask questions, including Senator Bobby Kennedy (D-NY), Sen. Henry M. Jackson (D-WA), and Senator Fred Harris (D-OK). The main attraction, of course, was the head of General Motors, James Roche. Roche was accompanied that day by legal counsel, Ted Sorensen, former aide to President John F. Kennedy.

At the hearing, Roche explained to the committee that GM had started its investigation of Nader before his book came out, and before he was scheduled to appear in Congress. GM wanted to know if Nader had any connection with the damage claims being filed against the corporation in legal actions regarding the Corvair. Roche said that his company certainly had legal right to gather any facts needed to defend itself in litigation. But he also added, “I am not here to excuse, condone or justify in any way our investigation” of Nader. In fact, in his statement Roche deplored “the kind of harassment to which Mr. Nader has apparently been subjected.” He added that he was “just as shocked and outraged” as the senators were.

Ribicoff asked Roche whether he considered this kind of investigation “most unworthy of American business.” Roche replied, “Yes, I would agree,” adding this was “a new and strange experience for me and for General Motors.” And Roche did apologize, saying at one point: “I want to apologize here and now to the members of this subcommittee and Mr. Nader. I sincerely hope that these apologies will be accepted.”

Nonetheless, Roche took the opportunity – no doubt at the advice of legal counsel – to publicly deny some of the more unsavory aspects of the Nader investigation that had been reported in the press. Roche testified that to the best of his knowledge the “investigation initiated by GM, contrary to some speculation, did not employ girls as sex lures, did not employ detectives giving false names…, did not use recording devices during interviews, did not follow Mr. Nader in Iowa and Pennsylvania, did not have him under surveillance during the day he testified before this subcommittee, did not follow him in any private place, and did not constantly ring his private telephone number late at night with false statements or anonymous warnings.”

Senator Robert Kennedy, in questioning Roche, agreed that GM was justified in the face of charges about the Corvair to make an investigation to protect its name and its stockholders. But Kennedy also questioned whether GM’s earlier statement of March 9th, which had acknowledged the investigation as a routine matter, wasn’t misleading or false in denying the harassment of Nader. Kennedy questioned whether the GM investigation of Nader hadn’t moved into intimidation, harassment, “or possibly blackmail.” Referring to the earlier GM press statement, Kennedy said: “I don’t see how you can order the investigation and then put out a statement like this [March 9th statement], which is not accurate. That, Mr. Roche, disturbs me as much as the fact that you conducted the investigation in the way that it was conducted in the beginning.” Roche said the March 9th statement may have been misleading but added that might have been due to lack of communications in GM. Kennedy expressed doubt that a firm such as GM could be that inefficient. “I like my GM car,” Kennedy said at the end of his questioning, “but you kind of shake me up.”

Committee members also questioned GM’s chief counsel, Aloysious Power, and assistant general counsel, Louis Bridenstine, as well as Vincent Gillen, the head of the detective agency. Gillen denied Nader’s charges. GM’s Power acknowledged ordering the investigation explaining that Nader was something of “a mystery man” – a lawyer who did not have a law office. GM also wanted to know about the man whose book was charging that GM’s Corvair was inherently unsafe. Kennedy remarked there was no mystery about Nader, that he was a young lawyer who had just come out of law school.

Ribicoff at one point referred to the surveillance of Nader, the questioning of his former teachers and friends, querries about his sex habits, etc., as pretty unsavory business. Ribicoff then asked Roche: “Let us assume that you found something wrong with his sex life. What would that have to do with whether or not he was right or wrong on the Corvair?,” to which Roche replied, “Nothing.”

Holding a copy of GM’s report on Nader in his hand, Ribicoff contended there was little in it about Nader’s legal associations or any possible connections with Corvair litigation. Nader had also reiterated for the committee that he had nothing to do with the Corvair litigation. Ribicoff contended the investigation “was an attempt to downgrade and smear a man.”

Richard Grossman, the publisher of Unsafe at Any Speed, later recalling Ribicoff’s manner during the hearing, paraphrased him, noting: “He said: ‘and so you [GM] hired detectives to try to get dirt on this young man to besmirch his character because of statements he made about your unsafe automobiles?’ Then he grabbed [the GM report], threw it down on the table and said, ‘And you didn’t find a damned thing’.”

Nader, earlier, had called GM’s investigation “an attempt to obtain lurid details and grist for the invidious use of slurs and slanders…” Nader also told the committee that he feared for democracy if average citizens were subject to corporate harassment whenever they had something critical to say about the way business operated.“They have put you through the mill, and they haven’t found a damn thing wrong with you.”

–Sen. Ribicoff to Ralph Nader

Ribicoff, meanwhile, practically anointed Nader as “Mr. Clean” at the hearing, finding him gleaming of character having survived the digging and scheming by GM’s private eyes. Ribicoff told Nader that he could feel pretty good about himself. “They have put you through the mill,” Ribicoff said of the GM investigators, “and they haven’t found a damn thing wrong with you.” A few weeks after the March 22, 1966 hearing it was also learned that the GM-hired detectives had also sought to find links between Ribicoff and Nader. One of Nader’s friends, Frederick Hughes Condon, a lawyer in Concord, New Hampshire, had been contacted by GM’s detective, Vince Gillen, on February 22, 1966 asking him about Nader’s relationship with Ribicoff. Ribicoff, however, said that he had met Nader for the first time the day he walked into the hearing room during his first committee appearance on February 11, 1966.

National Notice

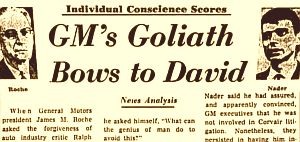

Washington Post story by Morton Mintz, “GM's Goliath Bows to David,” appeared on March 27, 1966.

The evening of the Senate’s March 22nd, 1966 hearing, in fact, Nader appeared on each of the three network news TV shows – this at a time when there were only three televisions channels. And in the next morning’s newspapers, the apology by GM was front-page news all across the country. The headline used on the front page of the Washington Post, for example, was: “GM’s Head Apologizes To ‘Harassed’ Car Critic.”

1966: Ralph Nader testifying in Congress.

Ralph Nader at the White House shaking hands with President Lyndon Johnson after bill-signing ceremony, September 9, 1966. |

The Washington Post also used a photo of the Nader-LBJ meeting at the highway bill signing. |

President Lyndon Johnson invited Nader to the White House for the signing of the highway safety bills. During the ceremony, LBJ remarked in his speech: “The automobile industry has been one of our Nation’s most dynamic and inventive industries. I hope, and I believe, that its skill and imagination will somehow be able to build in more safety—without building on more costs.”

Nader would later write of that day at the White House: “At the request of a New York Times reporter I prepared a statement for the occasion and walked from the nearby National Press Building to the White House… The atmosphere inside was upbeat and LBJ was passing out pens furiously while shaking everybody’s hand. At the time I recall thinking: Now the work really starts to make sure the regulators are not captured by the industry they are supposed to regulate…”

Nader Sues GM

Nor was Nader finished with GM. In fact, not long after the GM-Nader showdown on Capitol Hill, an attorney friend of Nader’s, Stuart Speiser, called him on the phone. Speiser had heard Roche apologize to Nader during the March hearings, and he suspected Nader might have a good shot at a lawsuit.

“I told Ralph I was sure GM expected to be sued and that they were probably prepared to pay a large sum, larger than any previous award, to bury their mistakes,” Speiser would later write in his own book, Lawsuit (1980), recounting their case against GM.

Speiser believed GM would be the perfect target because the company’s image suffered after publication of Unsafe at Any Speed. Nader, by contrast, would serve as the “knight in shining armor, champion of the consumer, the last honest man. . .”

In November 1966, Nader and Speiser sued GM for compensatory and punitive damages. GM’s attorneys tried multiple times to throw the case out of court by saying the carmaker was not responsible for any wrongdoing. Speiser proved that the independent private detective, Vincent Gillen, had acted directly on behalf of GM and used Gillen’s testimony to that effect against GM. More than two years after the suit was filed, GM agreed to pay Nader $425,000 – the largest out-of-court settlement in the history of privacy law. Nader used the settlement money to found several public interest groups, including the Center for Auto Safety.

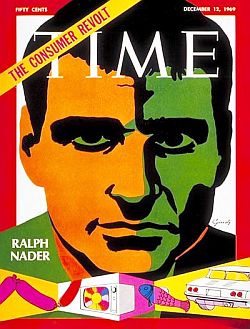

Dec. 12, 1969: Ralph Nader featured in Time magazine’s “consumer revolt” cover story. |

Media Coverage

During the late 1960s and early 1970s, Ralph Nader enjoyed rising popularity and increasing media coverage. He was becoming America’s leading consumer advocate, and he broadened his appeal by working for environmental protection, improved food safety, corporate accountability, and other causes. He soon began showing up on the covers of mainstream magazines such as Time and Newsweek, and on nightly news TV broadcasts.

In January 1968, Newsweek magazine featured him in knight’s armor in a cover story titled, “Consumer Crusader – Ralph Nader.” In December 1969, Nader made the cover of Time magazine for a covers story on “The Consumer Revolt.”

“To many Americans,” wrote Time, “Nader, at 35, has become something of a folk hero, a symbol of constructive protest against the status quo.”

And by the early 1970s, given his rising national following, Nader was being touted by some as a possible presidential candidate, as Gore Vidal would propose in an June 1971 Esquire piece shown at left. But Nader in the 1970s and beyond would continue to have a major impact on public policy – not only by his own actions and advocacy, but also that of a legion of young people he recruited and inspired.

These “Nader’s Raiders,” as they would be called by the press, churned out a continuing series of books and reports through the 1970s and 1980s, some of which helped revive and transform the art of investigative journalism. For that part of the story please see “Nader’s Raiders,” also at this website.

There is, of course, much more to the Ralph Nader story beyond his early struggles with GM and the auto industry covered here. Readers are directed to “Sources, Links & Additional Information” below which includes various websites and books profiling his long career.

In later years, Nader would take a turn toward running for public office himself, launching bids for President of the United States in 1996, 2000, 2004, and 2008.

In the 2000 election, running nationwide as the candidate of the Green Party, Ralph Nader won nearly three million votes, close to three percent of the votes cast. That election proved to be the closest presidential election in American history – in which the deadlocked outcome between George W. Bush and Vice President Al Gore was resolved by the U.S. Supreme Court in Bush’s favor.

Ralph Nader campaigning for President, 2008.

David Booth, writing in 2010 at the 45th anniversary of Unsafe and Any Speed in his “The Fast Lane” column for MSN.com, observed, for example:

…Love or hate him, Nader is single-handedly responsible for much of the modern automotive safety technology that now cocoons us. Never mind that he has since become a caricature of the American political scene….[W]ere it not for Unsafe, there probably might never have been a National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA). Anti-lock brakes, air bags and the three-point [safety belt] harness might still be a glint in some Swedish engineer’s eye had not Nader taken up his one-man crusade…

Part of the cover of the 25th anniversary paperback edition of “Unsafe at Any Speed,” published by Knighstbridge Publishing Co. in 1991.

Nader has been named to lists of the “100 Most Influential Americans” by Life, Time, and The Atlantic magazines, among others. In 2016, he was inducted in to the Automotive Hall of Fame.

Through the 2010s, Ralph Nader continued his fight on behalf of consumers and an active and aware citizenry — writing books and a weekly web column, making public appearances, and advocating for numerous causes. See also at this website part 2 of this story, “Nader’s Raiders.” Also of possible interest at this website, see: “Smog Conspiracy: DOJ vs. Detroit Automakers,” a 1969 legal battle in which Ralph Nader was a key player. For other stories on politics at this website please see the “Politics & Culture” category page, and on business and the environment, the “Environmental History” page. Thanks for visiting — and if you like what you find here, please help support the research and writing at this website with a donation. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

____________________________________

Date Posted: 31 March 2013

Last Update: 5 November 2021

Comments to: jackdoyle47@gmail.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “GM & Ralph Nader, 1965-1971,”

PopHistoryDig.com, March 31, 2013.

____________________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

A young Ralph Nader with the Washington beltway in the background, August 1967. Associated Press photo. |

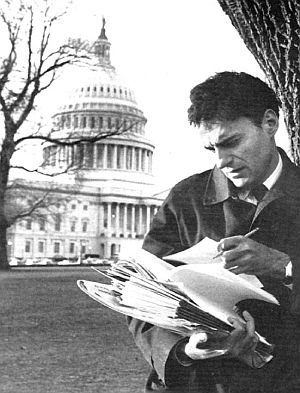

Ralph Nader on Capitol Hill, early- mid-1970s. |

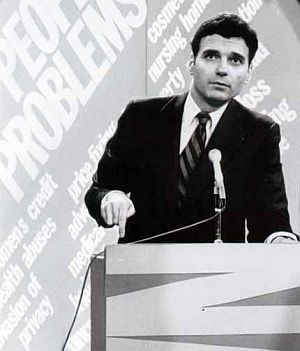

Ralph Nader at a Public Citizen press conference, 1970s. |

Ralph Nader, in public forum, engaging his audience. |

August 1976: Democratic Presidential nominee, Jimmy Carter, and consumer advocate Ralph Nader, talk with reporters outside of Carter’s home in Plains, Georgia. |

February 24, 2008: Ralph Nader on “Meet the Press” with Tim Russert, in Washington, DC where he announced he would run for President in 2008 as an independent. |

Ralph Nader, “The Safe Car You Can’t Buy,” The Nation, April 11, 1959.

James Ridgeway, “Car Design and Public Safety,” The New Republic, September 19,1964.

Ralph Nader, Unsafe at Any Speed, New York: Grossman Publishers, 1965.

Richard F. Weingroff, “Epilogue: The Chang- ing Federal Role (1961-1966),” President Dwight D. Eisenhower and the Federal Role in Highway Safety,” Highway History, U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration, Washington, D.C.

Ralph Nader, Unsafe at Any Speed, chapters available at, NaderLibrary.com.

“Unsafe at Any Speed,” Wikipedia.org.

David Bollier, Citizen Action and Other Big Ideas: A History of Ralph Nader and the Modern Consumer Movement, Center for Study of Responsive Law, Washington, D.C., 1991, 138 pp.

“Ralph Nader: Biographical Information,” The Nader Page, Nader.org.

“Ralph Nader, Biography,” American Acad- emy of Achievement.

“An Unreasonable Man: Illustrated Screen- play & Screencap Gallery,” American- Buddha.com.

“Lawyer Charges Autos Safety Lag; In Book, He Blames ‘Traffic Safety Establishment’,” New York Times, November 30, 1965, p. 68.

“Car Makers Deny A Lag In Safety; Dispute Charges by Book of Stress on Power and Style,” New York Times, December 1, 1965, p. 37.

“1965 – Ralph Nader Publishes Unsafe at Any Speed,” Timeline, BizJournalism History.org.

“This Day in History, November 30, 1965: Unsafe at Any Speed Hits Bookstores,” History.com.

Morton Mintz, “Auto Safety Hearings Set Feb. 1,” Washington Post, Times Herald, January 14, 1966, p. A-5.

U.S. Senate, Hearings on Highway Safety, Senate Subcommittee on Executive Reorganization, Committee on Government Operations, Washington, D.C., Thursday, February 10, 1966.

“Writer Predicts ‘No Law’ Auto Act; Charges Harassment,” Washington Post, Times Herald, February 11, 1966, p. A-3.

Morton Mintz, “Car Safety Critic Nader Reports Being ‘Tailed’,” Washington Post, February 13, 1966.

Richard Corrigan, “Behind the ‘Chrome Curtain’,” Washington Post, Times Herald, February 21, 1966, p. A-3.

Charles C. Cain, (AP), “GM Finally Fights Critics on Safety; Cites Results, Takes Stand, Attacks Book,” Washington Post, Times Herald, February 27, 1966, p. L-3.

Morton Mintz, “LBJ Asks $700 Million Traffic Safety Program,” Washington Post, Times Herald March 3, 1966, p. F-8.

Walter Rugaber, “Critic of Auto Industry’s Safety Standards Says He Was Trailed and Harassed; Charges Called Absurd,” New York Times, March 6, 1966, p. 94.

Richard Harwood, “‘Investigators’ Hound Auto Safety Witness,” Washington Post, Times Herald, March 7, 1966, p. A-3.

United Press International, “Probe of Nader Harassment Report Is Asked,” Washington Post, Times Herald, March 9, 1966, p. A-9.

Walter Rugaber, “G.M. Acknowledges Investigating Critic,” New York Times, March 10, 1966, p. 1.

“Ribicoff Summons G.M. on Its Inquiry Of Critic; Head of Senate Safety Panel Plans Hearing March 22,” New York Times, March 11, 1966.

Richard Harwood, “GM Chief Called to Quiz On Probe of Auto Critic,” Washington Post, Times Herald, March 11, 1966, p. D-6.

James Ridgeway, “The Dick,” The New Republic, March 12, 1966.

Fred P. Graham, “F.B.I.. Will Enter Auto Safety Case; Inquiry Ordered on Charge of Intimidation of Critic,” New York Times, March 12, 1966.

United Press International, “Nader Testifies Wednesday Before Magnuson’s Panel,” New York Times, March 14, 1966.

Richard Harwood, “Sorensen Expected At Nader Quiz Today,” Washington Post, Times Herald, March 22, 1966, p. A-1.

Jerry T. Baulch, Associated Press, “GM’s Head Apologizes To ‘Harassed’ Car Critic,” Washington Post, Times Herald, March 23, 1966, p. A-1.

Associated Press, “General Motors’ Head Apologizes To Critic For Probe Harassment,” March 23, 1966.

Walter Rugaber, “G.M. Apologizes for Harassment of Critic,” New York Times, March 23, 1966, p. 1.

“The Corvair Caper,” Washington Post, Times Herald, March 24, 1966, p. A-24.

Chris Welles, “Critics Take Aim At Auto Makers: The Furor Over Car Safety,” Life, March 25, 1966, pp. 41-45.

Bryce Nelson, “GM-Hired Detective Sought to Find A Link Between Ribicoff and Nader,” Washington Post, Times Herald, March 26, 1966, p. A-1.

Morton Mintz, “GM’s Goliath Bows to David,” Washington Post, Times Herald, March 27, 1966, p. A-7,

“What’s Good for G.M.,” Editorial, New York Times, March 27, 1966.

Morton Mintz, “The Second of a 1-2 Punch at Automen,”Washington Post, Times Herald, March 29, 1966, p. A-14.

George Lardner Jr., “Private Eye Accused of Roving,” Washington Post, Times Herald, March 30, 1966, p. A-4.

Morton Mintz, “Minimum Tire Safety Standards Approved by Senate, 79 to 0,” Washington Post, Times Herald, Mar 30, 1966, p. A-6.

“Investigations: The Spies Who Were Caught Cold,” Time, Friday, April 1, 1966.

Morton Mintz, “Nader Assails Car Makers For Secrecy on Defects,” Washington Post, Times Herald, April 15, 1966, p. A-1.

Morton Mintz, “U.S. Blames GM in Auto Accident; Case May Be 1st Government Try To Hold Manufacturer Responsible,” Washington Post, Times Herald, April 17, 1966, p. A-4

Morton Mintz, “Nader Raps GM, Ford On Faulty Seat Belts,” Washington Post, Times Herald, Aprril 26, 1966, p. A-1.

Drew Pearson, “Car Accident Reports Suppressed,” Washington Post, Times Herald, April 26, 1966, p. B-13.

Hobart Rowen, “Safety Factor Weighed in Corvair Slump,” Washington Post, Times Herald, May 1, 1966, p. L-3.

Morton Mintz, “Nader Sues GM and Detective for $26 Million,” Washington Post, Times Herald, November 17, 1966, p. A-1.

James Ridgeway & David Sanford, “The Nader Affair,” The New Republic, February 18, 1967, p.16.

Art Siedenbaum,”Crusader Nader and the Fresh Air Underground,” Los Angeles Times, 1968,

“Meet Ralph Nader,” Newsweek, January 22, 1968, pp. 65-67.

“An Explosive Interview with Consumer Crusader Ralph Nader,” Playboy, October 1968.

“Ralph Nader,”Wikipedia.org.

“Ralph Nader Bibliography,” Wikipedia.org.

“Consumerism: Nader’s Raiders Strike Again,” Time, Monday, March 30, 1970.

Editorial, “The Nader Settlement,”New York Times, Monday, August 17, 1970.

“The Law: Nader v. G.M. (Cont’d),” Time, Monday, August 24, 1970.

Nader v. General Motors Corp., Court of Appeals of New York, 1970.

Thomas Whiteside, The Investigation of Ralph Nader: General Motors Versus One Determined Man, New York: Arbor House, 1972.

Charles McCarry, “A Hectic, Happy, Sleepless, Stormy, Rumpled, Relentless Week on the Road with Ralph Nader,” Life, January 21, 1972, p. 45-55.

Charles McCarry, Citizen Nader, New York: Saturday Review Press, 1972.

Elizabeth Drew, Book Review,“Citizen Nader, by Charles McCarry,” New York Times, Sunday, March 19, 1972.

Sandra Hochman, “America’s Chronic Critic; Ralph Nader Finally Has the President’s Number,” People, February 28, 1977.

“Ralph Nader Interview: Making Government Accountable,” Academy of Achievement (Washington, D.C.), February 16, 1991.

U.S. Department of Transportation / Federal Highway Administration, “President Dwight D. Eisenhower and the Federal Role in Highway Safety – Photo Gallery,” DOT.gov.

Justin Martin, Nader: Crusader, Spoiler, Icon, Perseus Publishing, 2002.

Patricia Cronin Marcello, Ralph Nader: A Biography, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2004.

Joseph R. Szczesny, “GM: Powerful – and Paranoid,” Time, Tuesday, June 2, 2009.

T. Rees Shapiro, “Stuart M. Speiser, Attorney for Ralph Nader in GM Lawsuit, Dies at 87,” Washington Post, Thursday, October 28, 2010.

David Booth, MSN Autos, “Ralph Nader May Be Anti-Car, But You Should Still Thank Him,” MSN.com, November 2010.

Sheila T. Harty, “Ethics of Citizenship From a Nader Raider,” 2011, 12pp.

Timothy Noah, “Nader and the Corvair,” TNR.com, October 4, 2011.

David Bollier, Citizen Action and Other Big Ideas: A History of Ralph Nader and the Modern Consumer Movement, Chapter 1, The Beginnings, Nader.org.

“Ralph Nader Biography,” American-Bud- dha.com.

“Jerome Nathan Sonosky Dies” (Counsel/ staff director, Sen. Ribicoff subcommitte, auto safety hearings), Connection News- papers, April 12, 1012.

T. Rees Shapiro, “Obituaries, Jerome N. Sonosky, Lawyer,” Washington Post, March 30, 2012.

Paul Ingrassia, “How the Corvair’s Rise and Fall Changed America Forever,” The Great Debate/Reuters, May 9, 2012.

Ronald Ahrens, “GM Squandered Our Good Will, Setting off Years of Licks for Corporate America,” Baggy Paragraphs, July 20, 2012.

Stephen Skrovan and Henriette Mantel, An Unreasonable Man: Ralph Nader: How Do You Define A Legacy?, A Documentary Film, Discussion Guide, 7pp.

Karen Heller, “Ralph Nader Builds His Dream Museum – of Tort Law,” WashingtonPost .com, October 4, 2015.

____________________________________________