It was the ultimate in baseball – the final, showdown Game 7 of a World Series. The place was Forbes Field, a classic baseball park in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. It was October 13th, 1960, that time of year when the last warm days of summer begin to meet crisper fall afternoons. Excitement was already in the air generally, both in Pittsburgh and throughout the nation, as a presidential election race was also underway and a young man named John F. Kennedy was offering the country something new. Later that evening, in fact, Kennedy and his Republican opponent, vice president Richard Nixon, would debate on national television for the third time. But the business at hand in Pittsburgh that afternoon wasn’t politics; it was baseball.

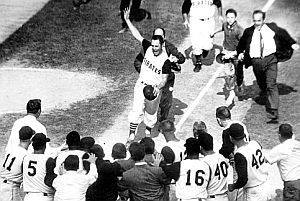

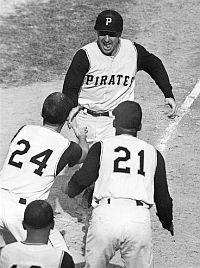

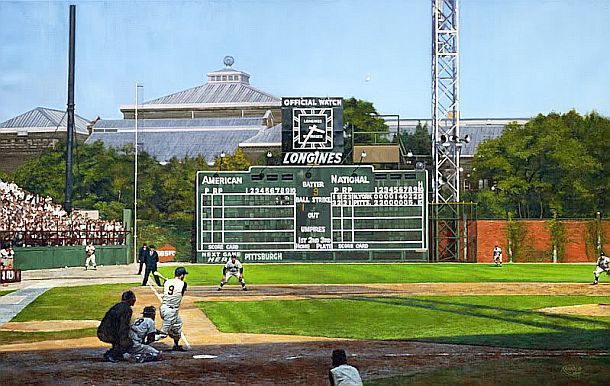

October 1960; Forbes Field, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: No. 9 of the Pittsburgh Pirates, Bill Mazeroski, has just hit a pitch that is heading for the trees beyond the left field wall. It is an historic home run, occurring in the bottom of the ninth inning in Game 7, a walk-off home run that wins the World Series, beating the favored NY Yankees. Photo, Marvin E. Newman. Click for copy.

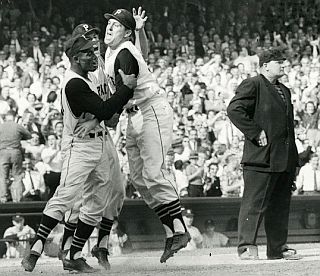

The New York Yankees and the Pittsburgh Pirates were tied in this World Series, each having won 3 games. Now, in the bottom of the ninth inning of their showdown Game 7, the score was tied, 9-to-9, as the numerals on the Forbes Field hand-operated scoreboard would reflect. However, a magical moment was about to unfold – “the Mazeroski moment” – shown above and named for Pirate second baseman, Bill Mazeroski, No. 9, who was then batting.

“Maz,” as he was called, had just hit a baseball that would leave the confines of Forbes Field. The clutch, game-winning home run marked Mazeroski in that instant — and for the ages — as a hero for hitting one of the most famous home runs in baseball history. In fact, the Mazeroski blast still stands today as the only World Series-winning walk-off home run in a game 7.

On some versions of the above photo, just off and above the upper right-hand corner of the scoreboard clock, the feint outlines of the baseball in flight can be seen. It was on a path to clear the left field wall where Yankee player, Yogi Berra, seen distantly in the outfield, is already reacting. (A colorized painting of this same scene in included at the very bottom of this story).

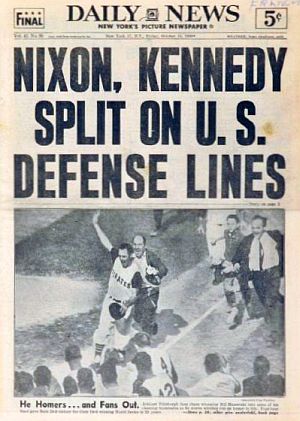

Oct 14, 1960: Headlines from the New York Daily News delivers the bad news to New York Yankee fans, showing Bill Mazeroski making his jubilant run to home plate.

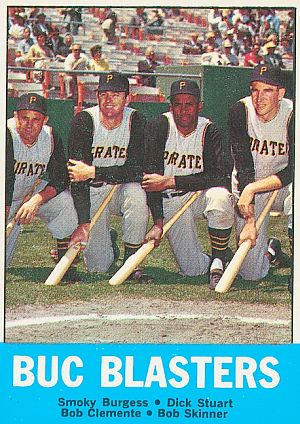

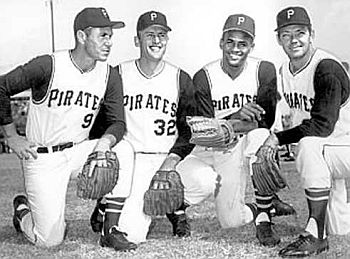

The Pittsburgh Pirates, of course, had good players of their own that year – among them Roberto Clemente, Dick Groat, Don Hoak, and pitchers Bob Friend, Vernon Law, and Elroy Face, among others. But the Yankees were still heavily favored to win. Few, if any bookies placing odds on the Series that fall had picked the Pirates to win. And for Pittsburgh, when it came to the New York Yankees, there were some long-lingering bad memories from the last time the Pirates and the Yankees faced off in a World Series. That was 1927, when the Yankees had Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig, both of whom proceeded to put on a home run clinic that intimidated and humiliated Pittsburgh, as the Yankees swept the Pirates in four straight games.

Pittsburgh in 1960 was also city that had a very long drought when it came to winning baseball titles. The Pirates had not won a World Series since 1925 and for much of the 1950s had been one of the worst teams in the majors. In fact, a particularly bad run of nine consecutive losing seasons was fresh in memory. Pittsburgh, in short, was then a city starved for baseball glory – and for that matter – sports glory of almost any kind. The Pittsburgh Steelers football team was then a dozen years away from winning their first playoff game. The Penguins ice hockey team was seven years away from being born. So, when the 1960 World Series came to town, there was a lot of pent-up hope and expectation – not only in Pittsburgh, but throughout the entire Western Pennsylvania region as well. What follows here is a recounting of some of that World Series, which had drama throughout and beyond “The Mazeroski Moment” – and there’s also a Bing Crosby connection. More on that later.

Time & Place

Pittsburgh in more recent times at the juncture of the Allegheny & Monongahela Rivers, with Cathedral of Learning visible in the far distance, top center, marking former location of Forbes Field.

In literature, Harper Lee had published her novel To Kill a Mockingbird in July, a book which would later win the Pulitzer Prize for the best American novel of 1960. And as already mentioned, the 1960 presidential election campaign was underway, with U.S. Vice-President Richard M. Nixon (R) running against U.S. Senator John F. Kennedy (D) of Massachusetts. At the 1960 Summer Olympic Games in September, a young boxer named Cassius Clay had won the gold medal in light-heavyweight boxing. This was also prime time for Frank Sinatra and his Las Vegas “Rat Pack” – the cool guys of that era – Dean Martin, Sammy Davis, Jr., Joey Bishop and Peter Lawford. At the box office in mid-October, Spartacus, starring Kirk Douglas as the slave-turned-gladiator rebel in ancient Rome, was the No. 1 movie. On the Billboard music charts that fall, “Save The Last Dance for Me” by the Drifters, “Georgia on My Mind” by Ray Charles, and “Are You Lonesome Tonight” by Elvis Presley were among the top hits.

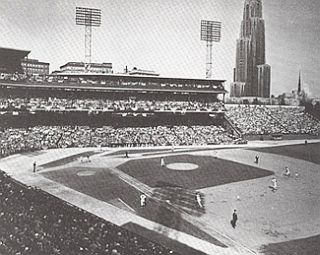

Forbes Field, Pittsburgh, PA, circa 1950s-1960s. |

Another shot of Forbes Field, which is located in the Oakland section of Pittsburgh, with the University of Pittsburgh’s “Cathedral of Learning” tower seen in this photo. |

The city of Pittsburgh, meanwhile, was remaking itself from its gritty, grimy past. Pittsburgh had risen as a 19th century industrial powerhouse on the avenues of commerce that were the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers, transporting coal and iron ore to the steel mills that helped build America. Following World War II, Pittsburgh launched civic revitalization and clean air projects known as the “Renaissance,” aimed at cleaning up the city’s sooty image. But Pittsburgh in 1960 was still very much that broad-shouldered, working-class city of coal, iron and steel. It was the town of Jones and Laughlin Steel, Pittsburgh Plate Glass, Alcoa, U.S. Steel, and Westinghouse. Pittsburgh, in short, was still very much a blue-collar town – capital of Western Pennsylvania, a region brimming full of loyal sports fans.

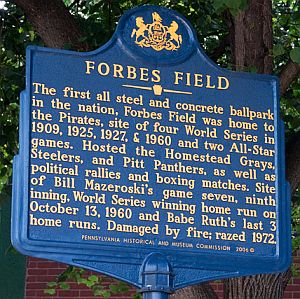

Then there was the beloved baseball park, Forbes Field. In 1908, city leaders approved plans for a baseball park in the Oakland section of the city. About a years later, Pirates owner Barney Dreyfuss opened a stadium at Forbes Field, which was the world’s first three-tiered steel and concrete stadium. The ball park was sited near the hills and trees of Schenley Park, and brought notice for its setting and design. Fittingly, the Prates played in the 1909 World Series there, with Honus Wagner among Pirate stars of that day, doing battle with the Detroit Tigers and Ty Cobb. The Pirates won that Series, besting Detroit 4 games to 3. Forbes Field, in fact, hosted two more World Series in 1925 and 1927, winning the 1925 Series by beating the Washington Senators 4 games to 3, and losing the 1927 Series to the Yankees, as already mentioned in a four game sweep. There were also two All-Star games played at Forbes, in 1944 and 1959.

Forbes Field was known for its ivy-covered outfield wall in left and left center field. It also had a hand-operated scoreboard topped with a large clock. The scoreboard was part of the left field wall. Lights were added later for night games.

In 1947, when the Pirates acquired slugger Hank Greenberg, the left field wall was moved in thirty feet and the bullpens located in the space between the wall and the scoreboard. This area this area then became known as “Greenberg Gardens.” Later, when Ralph Kiner joined the team, the Gardens became known as “Kiner’s Korner.”

Forbes Field also had claim to a share of baseball’s iconic moments, including Babe Ruth’s last game, played as a Boston Brave in 1935 – a game in which he hit his last three career home runs – #’s 712, 713 & 714 — the 3rd of which cleared the right field roof and traveled some distance beyond the park.

Forbes Field was the first home stadium of the Pittsburgh Steelers and was also used for football by the University of Pittsburgh “Pitt” Panthers. The Homstead Grays of the Negro Baseball League also played at Forbes. Boxing matches and political rallies were held there as well. On October 2, 1936, President Franklin D. Roosevelt addressed a crowd of 60,000 at Forbes Field during a campaign stop, defending his New Deal programs. Forbes Field was demolished in July 1971, as the Pirates used the newly-built Three Rivers Stadium as their home park until 2001, when the team moved to their present home field, PNC Park. But for the 1960 World Series, the first two games were played at Forbes Field, and the attendance for Game 1 on October 5th, 1960 was 36,676, filling the park.

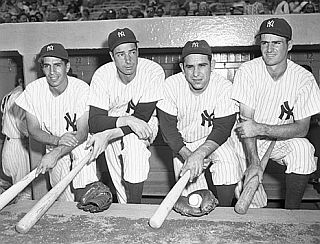

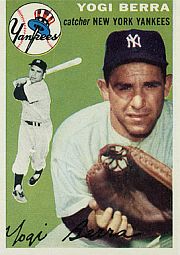

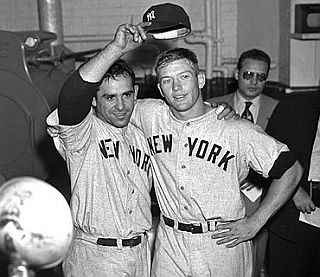

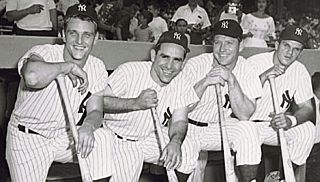

1960 New York Yankee All Stars, from left: Roger Maris, Yogi Berra, Mickey Mantle, and Bill “Moose” Skowron. |

Pittsburgh Pirates from the 1960 team shown a few years later, from left: Bill Mazeroski, Vernon Law, Roberto Clemente and Elroy Face. |

The 1960 Series

Yanks vs. Bucs

The 1960 New York Yankees and Pittsburgh Pirates had comparable records. The Yanks had won the American League pennant by eight games with a 97–57 record for a .630 win-loss average. The Pirates won the National League race by seven games with a 95–59 record and a .617 average.

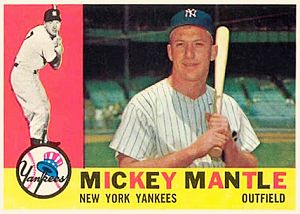

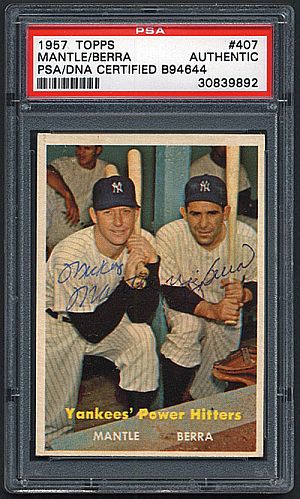

Still, the Yankees featured raw hitting power on a level just below that of 1927’s Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig, this time with Mickey Mantle and Roger Maris – the “M & M boys” as they would be called in the following year when the two sluggers engaged in a heated race for Babe Ruth’s home run record — which Maris would break hitting 61.

In the 1960 season, however, Maris hit 39 home runs with 112 RBIs and a .283 average. Mantle had 40 home runs that year, 94 RBIs, and a .275 average.

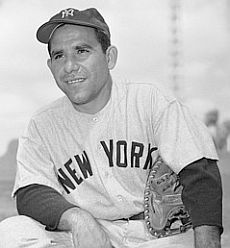

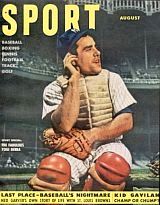

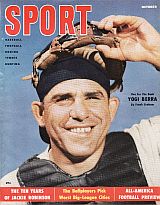

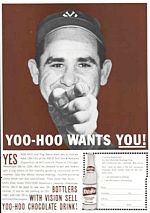

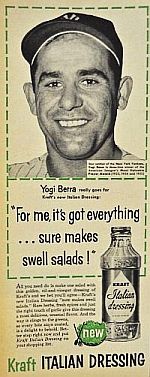

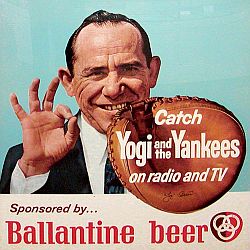

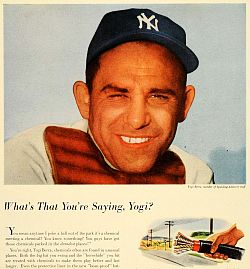

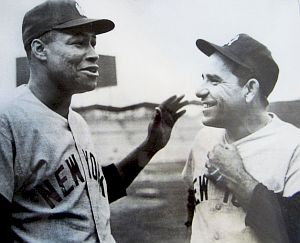

In addition to Maris and Mantle, there was also Yogi Berra (15 HR, 62 RBIs, and.276 avg.) and Bill “Moose” Skowron (26 HR, 91 RBIs, and .309). Catcher Elston Howard, who had not played a full season, could also hit for power. And shortstop Tony Kubek and third baseman Clete Boyer had more than 100 RBIs between them.

The Yankees’ core pitching staff had no 20 game winners among them, but included – Art Ditmar (15-9), Jim Coates (13-3), Whitey Ford (12-9), and Ralph Terry (10-8). Bobby Shantz was a top reliever, with a 5-4 record, 11 saves and a 2.79 ERA.

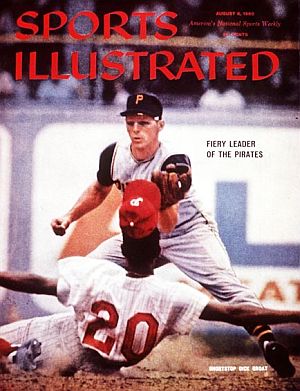

Pirate shortstop and 1960 NL MVP, Dick Groat, featured on the August 8th 1960 cover of Sports Illustrated. Click for copy.

Strong performances that year had come from Roberto Clemente, Dick Stuart and Dick Groat. Clemente compiled a .314 batting average in 1960 with 16 home runs and a team-leading 94 RBIs.

Dick Stuart, the Bucs’ home run leader that year with 23, also had 83 RBIs. Stuart had once hit 66 home runs in a single season in the minor leagues.

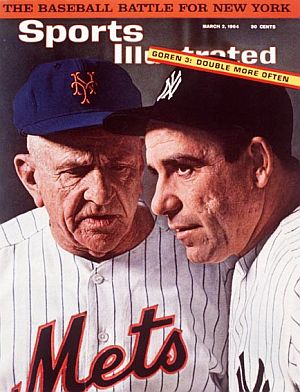

Dick Groat, the Bucs’ 29 year-old shortstop that year, had hit .325 with 189 hits. In August 1960, Groat made the cover of Sports Illustrated magazine, with the tagline, “Fiery Leader of the Pirates.”

Groat had been a Duke University basketball All-American and had grown up just a few miles from Forbes Field (click for separate story). As a kid, he had always wanted to play for the Pirates. In 1952, he got his wish.

Groat was signed by Branch Rickey, famous Brooklyn Dodger general manager (GM) who had brought Jackie Robinson into Major League baseball to break the “color barrier.” Rickey was then GM with the Pirate organization. After Groat signed with the Pirates, he soon became the team’s regular shortstop. In 1960, he would win the National League’s Most Valuable Player (MVP) trophy.

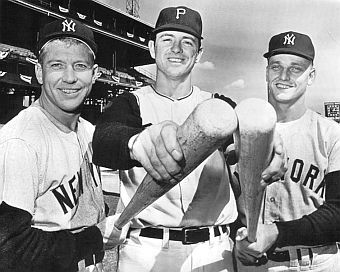

Promotional photo for the 1960 World Series with Mickey Mantle (L) and Roger Maris (R) flanking the Pirates’ Dick Stuart, who as a minor leaguer in 1956, hit 66 home runs.

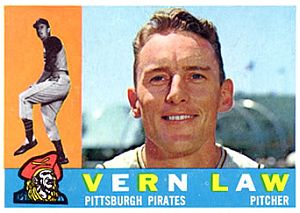

Pirate pitching in 1960 finished third in National League Earned Run Average (ERA). The team’s starters that year, led by Cy Young award winner Vernon Law (20-9), also included Bob Friend (18-12), Wilmer “Vinegar Bend” Mizell (13-5) [and later member of Congress], and Harvey Haddix (11-10).

“Little guy” Elroy Face (5′-9″) was one of the best reliever/closers then in baseball. Known for his “fork ball,” Face had a 10-8 record in 1960 with 24 saves.

Still, the Yankees were big favorites. On October 4th, a story in the New York Times used the headline: “Yanks 7-5 Choice To Capture Title; Odds Even on Opening Game — Pirates Calmly Study Reports on Bombers.” A second story from the Times that same day focused on Yankee power: “Pirates No Match in the Number of Distance Hitters; Bombers’ Attack Is Strong From Both Sides of Plate,” said the headline. But Pirates had a working-class grit about them, befitting their city, and had the support of those rooting for the underdog.

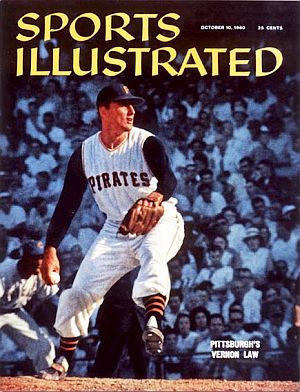

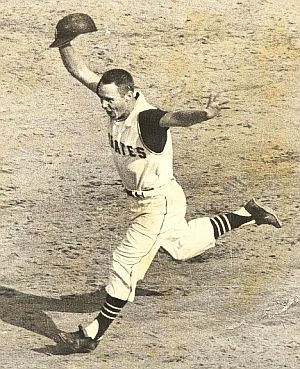

Pittsburgh ace, Vernon Law, pitched Game 1 of the 1960 World Series, which the Pirates won, 6-to-4. |

Pirate victory in Game 1 of the 1960 World Series is front-page news in Pittsburgh on October 6, 1960. |

Game 1

Pirates, 6-4

In Game 1 of the Series, played at Forbes Field, the Governor of Pennsylvania, David Lawrence, threw out the ceremonial opening pitch, and Billy Eckstine, Pittsburgh native, singer, and a bandleader of the swing era, sang the National Anthem. Vernon Law was the starting pitcher for the Pirates in Game 1, and the Yankees threw Art Ditmar.

In the opening half of the inning, Law retired the first two Yankee batters. Roger Maris, however, unloaded on Law for a home run, making Pirate fans a bit nervous. But the Pirates quickly came back, exhibiting the scrappy style of play that had become their trademark all year, putting together a walk, a double, two singles, and two stolen bases to produce three runs. Hitting by Dick Groat and Roberto Clemente had figured in the scoring, giving the Bucs the lead, 3-to-1.

In the fourth inning, New York cut the lead to 3-2 after Maris singled and then was moved around the bases by a Mantle walk, a fly ball by Yogi Berra, and then scored on a single by Bill Skowron. The Pirates came back again adding two more runs in 4th inning on a Bill Mazeroski two-run homer off Yankee reliever Jim Coates, making the count 5-to-2. The Bucs added another run in the 6th, making it 6-to-2.

In the top of the eighth inning, however, two Yankee singles with no outs were enough to bring in Elroy Face to relieve Vernon Law. Face managed to strike out Mantle and Skowron, with Berra making a fly out. The Yankees’ Elston Howard, however, ripped Face for a two-run homer in the ninth, cutting the score to 6-to-4, which proved to be enough, as the Pirate infield turned a double play to end the game. Still the Yankees collected 13 hits in the game, while the Pirates had eight. The next day, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette featured the home team’s Game 1 victory on the front page, also mentioning the two-run home run by Mazeroski as a key ingredient in the victory.

Oct 1960: Mickey Mantle, surrounded by press, celebrates with an Iron City beer in locker room after hitting two home runs in Game 2 of the 1960 World Series. Art Rickerby /Time-Life

Yankees, 16-3

Yankee power was on full display in a 16-3 trouncing of the Pirates in Game 2 of the 1960 World Series. Mickey Mantle hit two home runs in the game – a two-run blast in the 4th inning and a three-run shot in the 7th. Bob Turley was the starting pitcher for the Yankees in that game and Bob Friend for the Pirates.

The Pirates and Friend were still in the ball game through five innings when the score was 5-to-1 Yanks. But the wheels came off in the 6th inning, as the Yankees sent 12 men to the plate scoring 7 runs on seven hits, with one Pirate error and a passed ball adding the woes. After Friend was knocked out, he was followed by five Pirate relievers trying to hold the Yankees down.

For the Yankees, in addition to Mantle’s two home runs, Tony Kubek had three hits, while McDougald, Skowron and Howard each had two, a few of which went for extra bases. Although the Pirates only managed to score three runs, they had 13 hits as well, with Clemente, Nelson, Cimoli, and Burgess each having two apiece.

With the Series tied at one game each, the scene then shifted to Yankee Stadium in the Bronx, New York.

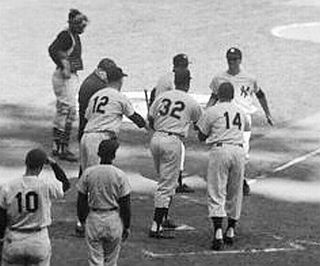

Oct 8th, 1960, Game 3, Yankee Stadium: Bobby Richardson being greeted at home plate by Gil McDougald (12), Elston Howard (32) and Bill Skowron (14) for his first inning Grand Slam home run. Tony Kubek (10) was on deck.

Yankees, 10-0

On Saturday, October 8th. at about 2:40 pm in the afternoon, some 70,000 fans filled Yankee stadium – nearly twice what the turnout had been for Game 1 at Forbes Field. Yankee pitcher, Whitey Ford, who had been 12-9 that season, was the starting pitcher for the Yanks, while Vinegar Bend Mizell got the nod for the Pirates.

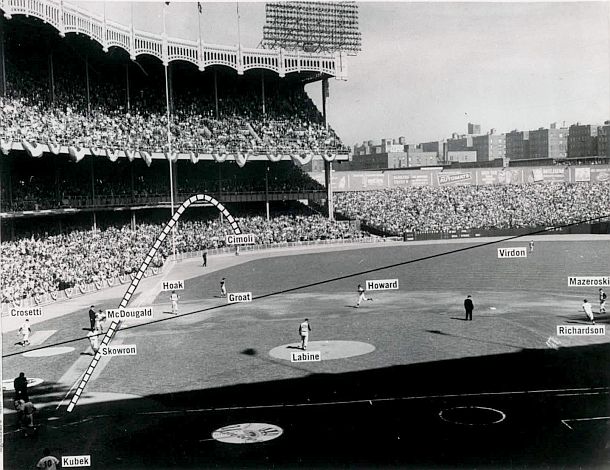

However, another lopsided Yankee affair soon followed, as both Mizell and Pirates reliever, Green were knocked out in the first inning. The Yankees tallied 6 runs on 7 hits in that inning alone, featuring a grand slam home run by Yankee second baseman Bobby Richardson.

Four more Yankee runs were added in the 4th inning with Mantle contributing a two-run home run and Richardson a two-run single, giving him total of 6 RBIs for Game 3. Mantle went 4-for-5 that game. Whitey Ford pitched the entire nine innings for the Yanks, giving up only four Pirate hits – to Clemente, Stuart, Mazeroski and Virdon. Final score, Yankees 10, Pirates 0. The Yankees were feeling pretty superior by this point.

Oct 8th: A wire service photo showing the route of Bobby Richardson’s Grand Slam home run in the 1st inning of Game 3 of the 1960 World Series at Yankee Stadium, with identifying labels provided for Yankee and Pirate players.

Oct 10th, 1960 edition of Sports Illustrated with Pittsburgh Pirate pitcher Vernon Law on cover. Click for copy.

Pirates, 3-2

On Sunday, October 9th at Yankee Stadium, at about 2:30pm in the afternoon with some 67,000 fans attending, Game 4 of the 1960 World Series began. Pirate pitcher Vernon Law started his second game for the Pirates, while the Yankees went with Ralph Terry.

Law held the Yankees to two runs – one, a Bill Skowron home run in the 4th, and a second on an infield double-play that scored Elston Howard in the bottom of the 7th.

The Pirates, however, didn’t get a hit until the fifth inning, when Gino Cimoli singled and Smoky Burgess got on with a ground ball. Two outs followed, but thanks to Law, the runners moved along when he doubled to left, scoring Cimoli. Law, in fact, had two hits that game. Virdon then singled, which sent Burgess and Law in to score, making the count 3-to-1 Pirates.

After the Yanks collared a few hits in the seventh scoring one run and leaving runners on base with one out, Elroy Face was called in to relieve Vernon Law. The Yankees’s Bob Cerv then hit a long drive off of Face to right center field that looked like certain trouble until sprinting centerfielder Bill Virdon made a spectacular one-hand catch, falling down at the wall as he did. Face retired the next batter for the final out in the 7th, and also the next three Yankees in order in the 8th inning. In the ninth, Bill Skowron gave the Pirate a scare when he hit a ball that had home run distance, but went foul. Don Hoak then made a good defensive play on Skowron’s next hard hit ground ball to third for one out, while Face retired the next two Yankees in order to preserve the Pirate win, 3-to-2. The Series was now tied at two wins each.

Harvey Haddix was the winning pitcher in Game 5 of the 1960 World Series.

Pirates, 5-2

On Monday, October 10, 1960, also at Yankee Stadium, the Pirates managed another victory, 5-to-2, as Pirate pitcher Harvey Haddix shut down the Yankees for the most part. The Pirates had a three-run second inning capitalizing in part on a Yankee error on the base paths.

Here’s how that play went down: the Pirate’s Dick Stuart had singled, but was forced out on a Clemente grounder. Smoky Burgess then doubled sending Clemente to third. Don Hoak hit a grounder to short, which Yankee shortstop Tony Kubek fielded and threw to McDouglad at third, attempting to get Burgess out as he tried to reach third. Clemente, meanwhile, had already scored. Kubek’s throw to third for Burgess got away from McDouglad and all hands were safe. Mazeroski, next up, doubled, sending in two more runs.

Harvey Haddix generally pitched a good game for the Bucs, recording six strikeouts and giving up just two runs — one in the second and a home run to Roger Maris in the 3rd. He kept Yanks tied up through 6 and one-third innings and left with a 4-2 Pirate lead. The Pirates added a run in the top of the 9th, giving them a 5-to-2 lead. Elroy Face, who had already relieved Haddix, then closed out the game. The Pirates now had a 3-2 lead in the Series and were heading home for Game 6, and if needed, Game 7.

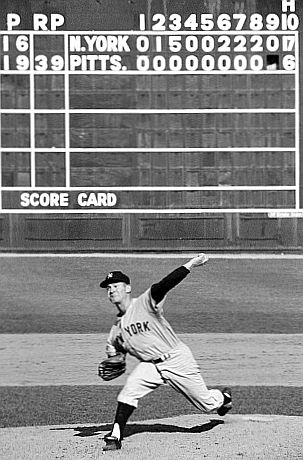

Yankee Whitey Ford in the 9th inning of Game 6 of the 1960 World Series at Forbes Field, with scoreboard telling the tale. Yanks 12, Pirates 0. Photo, N. Leifer

Yankees, 12-0

Back at Forbes Field in Pittsburgh for Game 6, Whitey Ford made his second Series start for the Yankees, and he didn’t disappoint. Ford shut out the Pirates, going the distance over nine innings allowing 7 hits but no runs.

Whitey’s teammates, meanwhile, pounded out 17 hits and 12 runs to take Game 6 by a count of 12-0. Although no Yankee homers figured in the final math, Berra, Mantle, Maris, and Skowron all collected hits. Bobby Richardson enjoyed another big game, with a pair of triples and three RBIs.

The Series was now tied 3-to-3, heading into the decisive Game 7.

Game 7

Pirates, 10-9

In the winner-take-all showdown game of the 1960 World Series, some 36,683 fans were on hand at Forbes Field. Yankees’ manager Casey Stengel went with Bob Turley as his team’s starting pitcher. Turley was the winning pitcher in Game 2. The Pirates employed their ace, Vernon Law, the winning pitcher in Games 1 and 4.

The Pirates struck first, knocking out Turley in the first inning as Rocky Nelson homered with Skinner on base, giving the Pirates an early 2–0 lead. The Pirates then added two more runs in the next inning, extending their lead to 4-0. Things were looking promising in Steel Town. Yankee power, meanwhile, had been shut down until the 5th inning when Bill Skowron hit a lead-off home run. But it was still 4-to-1, Pirates. Bobby Shantz began pitching for the Yankees in the third inning, and the Bucs were held scoreless through the seventh, during which time the Yankees had pulled ahead.

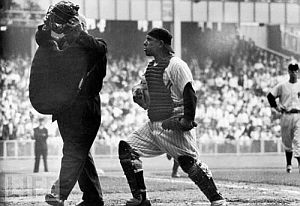

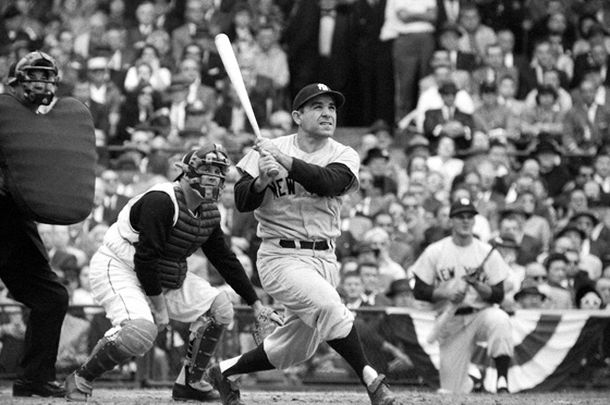

In the 6th inning the Yankees scored four runs to take the lead at 5-to-4. Bobby Richardson led off the inning with a single, followed by a walk to Tony Kubek. Roger Maris popped out but Mantle hit a single driving in one run. With Kubek and Mantle on base, Yogi Berra then ripped a three-run homer, a key blow, giving the Yanks a 5-4 edge.

Yogi Berra hitting a 3-run home run for the NY Yankees against the Pittsburgh Pirates at Forbes Field in the 6th inning of Game 7 of the 1960 World Series, giving the Yanks a 5-4 lead. Photo: N. Leifer / Sports Illustrated.

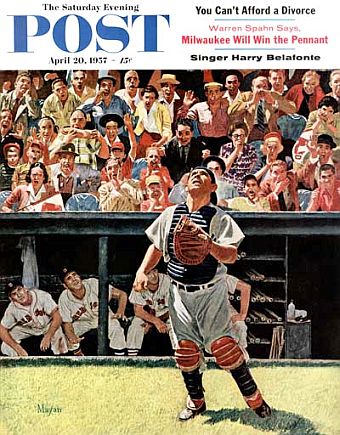

The 7th inning of Game 7 was scoreless for both sides. However, in that inning, the Pirates had a chance for some runs. Smoky Burgess led off with a base hit, and Murtaugh sent in a faster pinch runner for Burgess who would then be replaced in the lineup by back-up catcher Hal Smith. Burgess was a good hitter, so it was a tough decision for Murtaugh to take him out. But the gamble fizzled as the next two batters came up empty: Don Hoak lined out and Mazeroski hit into a double play. It was still 5-to-4 Yanks. Then came the 8th inning with Yankee power again coming to plate – Maris, Mantle and Berra. However, this time Maris and Mantle both made infield outs while Berra walked. But then other Yankees stepped up… – two singles and a double followed, adding two more runs, putting the Yanks still further ahead, 7-to-4.

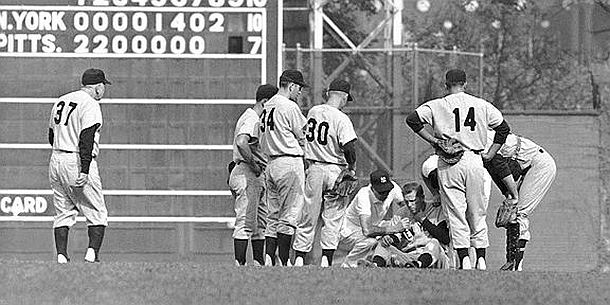

By the bottom of the eighth inning, things were not looking good in Pirate town. Down by three big runs, there were only six outs remaining. But the Pirate hitters went to work. They opened the inning with a single by Gino Cimoli, who had pinch-hit for Face. Virdon was next, and he hit a sharp ground ball to short for what appeared to a double-play ball. Instead, the ball took a bad hop on the rough infield and hit Yankee shortstop Tony Kubek in the throat, sending Kubek to the turf and stopping the game. It was later reported that Kubek had blood in his throat and having trouble breathing as his windpipe swelled . A conclave of Yankees, and manager Casey Stengel, came on the field to Kubek’s aide, and he was taken out of the game.

8th inning, Game 7, 1960 World Series, manager Casey Stengel (37), coming to see injured Yankee shortstop, Tony Kubek, hit in the Adams Apple of his throat after a ground ball took a bad hop, swelling his wind pipe.

As play resumed, the Pirate batter, Bob Skinner, was called upon to bunt, which he did, moving the runners to second and third. Nelson came up next, and flied out to shallow right field, with no runners moving. Clemente came to the plate next, fighting off a series of pitches with foul balls, and breaking his bat at one point. He then hit a ground ball chopper that went wide of first base, which Skowron fielded. Yankee pitcher, Coates, was supposed to cover first base, but had initially gone for the ball too, and was unable to recover quickly enough to beat Clemente to the bag, who was safe at first. In the process, Pirate base runner Bill Virdon scored, cutting the Yankee lead to 7-6.

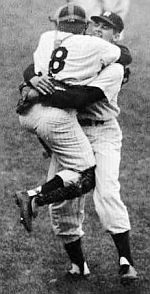

Roberto Clemente, with Dick Groat behind him, gives Hal Smith a celebratory lift for hitting a 3-run home run giving the Pirates a 9-to-7 lead over the NY Yankees in the bottom of 8th inning, Game 7, 1960 World Series. Click for autographed photo.

Next up was back-up Pirate catcher, Hal Smith, who had been sharing catching duty during the season with starter Smoky Burgess, and had come into the game after Burgess was lifted for a pinch runner earlier. Yankee pitcher Jim Coates took Smith to a 2-and 2 count, and then threw a him a low fastball. Smith connected with the pitch solidly, sending it soaring to left field, over the head of left fielder Yogi Berra and over the wall – a three-run homer scoring himself, Groat and Clemente.

TV announcer Mel Allen was astonished, saying that Smith’s 2-strikes- 2-outs home run “will be one of the most dramatic base hits in the history of the World Series” – a hit that “will long be remembered.” Smith’s homer proved to be a very big deal – at least for the moment – but would be soon be overshadowed and historically buried by what was yet to come. Yet, for the moment, the Pirates now led by a score of 9-to-7 thanks to Smith’s heroics.

Out on the pitching mound, meanwhile, the Yanks replaced Coates with Ralph Terry, who then recorded the third out in the Pirates big 8th inning by getting Don Hoak to fly out to left. But the damage had been done. Now, heading into the top of the 9th inning, it was the Yankees under the gun with only three outs remaining and the Pirates up by two runs, 9-to-7.

Game 7: Mickey Mantle’s single scored Richardson and moved McDougald to third, who later scored, tying the game, 9-to-9.

With two outs, Yogi Berra was next up, and hit a short grounder to first snared by Pirate first baseman Rocky Nelson, who stepped on the bag for the second out. Mickey Mantle, who was on first base, had started for second on Berra’s grounder, but saw he had no chance to make it there, and quickly reversed course back to first base, adroitly avoiding a tag by Nelson. Had Mantle been caught, it would have been the third out. Meanwhile, McDougald, who had been on third base, had scored, tying the game, 9-to-9. The next batter, Bill Skowron, grounded to short, which forced Mantle out at second base to end the inning.

October 13th, 1960: Students at the University of Pittsburgh’s Cathedral of Learning had a special perspective on Forbes Field below as they cheered the Pirates during Game 7 of the World Series. Photo, George Silk/Life. Click for related photo.

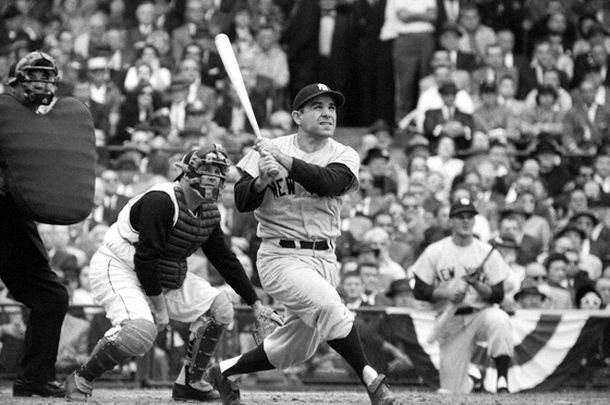

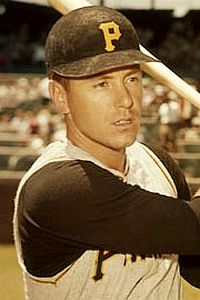

Now it was the bottom of the ninth inning, with home team Pittsburgh coming to bat. One run, scored at any time that inning, was all the Pirates needed to win the World Series. Yankee pitcher, Ralph Terry, who had made the final Pirate out in the eighth inning, returned to the mound for the bottom of the ninth. His job was to hold the line, keep the Pirates off the bases, and maintain the 9-to-9 tie score so the Yanks could hit again in the top of the 10th inning. The first man he faced was Pirate second baseman, Bill Mazeroski. Maz was having a pretty decent Series (in fact, he would go 8-for-25 over the seven games and bat .320 for the Series ), and although he had hit one home run earlier in the Series, in Game 1, he was still not regarded as a home run threat. During the 1960 season Maz had hit 11 home runs.

October 13th, 1960: Pittsburgh Pirate, Bill Mazeroski, just after hitting a Ralph Terry pitch in the bottom of the ninth inning at Forbes Field in Game 7 of the 1960 World Series that would sail over the left field wall to win the Series.

Terry’s first pitch to Mazeroski was a fast ball down the middle but high, for a ball. Next came a pitch lower in the hitting zone which Mazeroski unloaded on with a good swing. The ball popped off the bat and soared high into the afternoon sky heading toward and then over the left field wall. Bill Mazeroski had just made his Pittsburgh Pirates the 1960 champions of baseball. As NBC’s TV announcer, Mel Allen, called Mazeroski’s historic hit that afternoon:

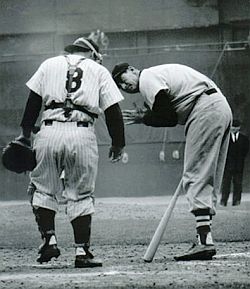

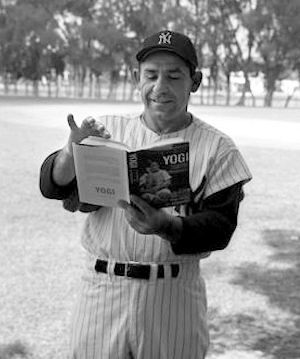

Yankee Yogi Berra watched two late-inning Game 7 Pirate home runs go over the Forbes Field left field wall: one to tie the game by Hal Smith and one to win it by Bill Mazeroski.

…There’s a drive into deep left field, look out now… that ball is going, going, gone! And the World Series is over! Mazeroski… hits it over the left field fence, and the Pirates win it 10–9 and win the World Series!

Chuck Thompson, a local radio announcer, also captured some of the action in his call:

,,,[H]ere’s a swing and a high fly ball going deep to left, this may do it!… Back to the wall goes Berra, it is…over the fence, home run, the Pirates win!… (long pause for crowd noise)… Ladies and gentlemen, Mazeroski has hit a one-nothing pitch over the left field fence at Forbes Field to win the 1960 World Series for the Pittsburgh Pirates…

Forbes Field was a ballpark with fairly deep outfield fences, and where Mazeroski hit the ball to left-center field, it went over the 18-foot ivy-covered brick wall near the 406 marker, with estimates that it likely traveled 430 feet or so – a very respectable World Series-winning clout.

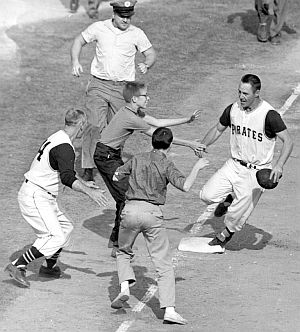

As the Pirates bench and Forbes Field erupted, Mazeroski, running hard to first base, came around the bag and realized his hit had left the yard and what he had just done. By the time he reached second base, fans began running onto the field, some coming toward him, trying to greet him and/or run the bases with him. In order to make the Pirate victory official, it was imperative that Mazeroski touch each bag and reach home plate for that final 10th run to be tallied.

Bill Mazeroski, on his home run trot, begins celebrating in earnest between 2nd and 3rd base on his way home. |

At 3rd base, well-wishing fans begin to greet Maz as Pirate third base coach, Frank Oceak, joins the party. |

Continuing his run around the bases midway between second and third, Mazeroski began waving with one arm and holding his batting helmet in the air with the other. Approaching third base, a couple of kids and a few other fans came alongside him, trying to offer their congratulatory pat-on-the-back or run along with him.

As he made the turn at third base there were a few more fans and some security guards and police were coming onto the field to help control the crowd and protect the players. In the stadium, the crowd was screaming wildly, with fans hugging one another, some crying with joy. As Mazeroski came down the third base line toward home plate, a mob of his teammates and some fans awaited him. There as well was home plate umpire Bill Jakowski, positioned between a couple of the waiting Pirates to make sure Mazeroski touched the plate. By then the field began to fill up with fans, along with state and local police, as the ballplayers tried to make their way to the clubhouse.

The Yankees. After Mazeroski’s homer, the Yankees stood around their dugout in stunned disbelief. The Pirates had been outscored, outhit, and outplayed by the Yankees, but had managed to emerge with the victory.

The Yankees, in fact, were the winners of the Series, statistically. They had out-scored the Pirates 55–27, out-hit them 91–60 with a better batting average, .338 to .256; out-homered them 10-to-4; and out-pitched them, led by Whitey Ford’s two complete-game shutouts and a team composite ERA of 3.54- to-7.11. Despite their statistically superior performance, the Yanks still lost.

Years later, Mickey Mantle was quoted as saying that losing the 1960 World Series was the biggest disappointment of his career, the only loss, amateur or professional, over which he cried actual tears.

Photographers. The Pittsburgh Post- Gazette had an enterprising photographer in 1960 named Jim Klingensmith who managed to capture Mazeroski’s home run and also the sequence of shots of Mazeroski bounding around the bases after he realized what he had done.

Sometime before Game 7, Klingensmith had scouted out the best spot in Forbes Field for taking what he hoped would be some good shots of the final World Series game that year.

On game day, with help from his son and a friend, he used a ladder and climbed atop the grandstand rooftop behind home plate. Once there, he kept the ladder with him to make sure he could get back down, and also to prevent competitors from encroaching on his territory.

From this perch, Klingensmith had a great perspective on the park that enabled him to make some priceless shots, a few of which now reside in the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, NY.

Also at the ball park that day was photographer Marvin E. Newman, who captured the Mazeroski moment in a classic shot of the field, scoreboard, and Longines clock that appears at the top of this story. Life magazine photographer George Silk, meanwhile, was on the roof of the nearby Cathedral of Learning at the University of Pittsburgh where he recorded his classic photo shown earlier of Pitt students cheering the Pirates on.

|

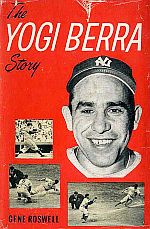

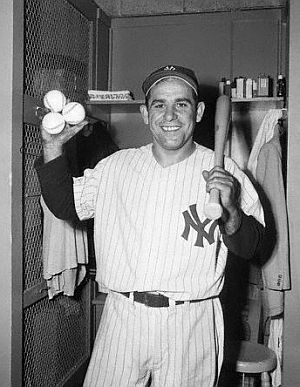

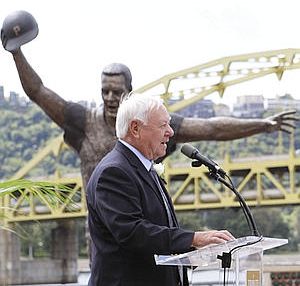

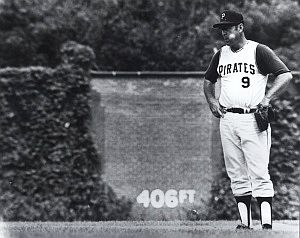

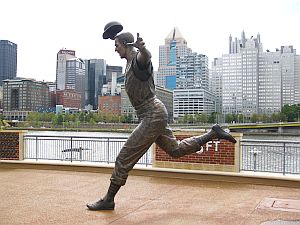

Bill Mazeroski  Bill Mazeroski, circa 1960s. But Bill opted instead for minor league baseball, signing with the Pittsburgh Pirates and rising in their farm system to the Hollywood Stars of the Pacific Coast League. Midway through the 1956 season with the Stars and batting .306, the Pirates brought Bill Mazeroski up to the majors. He was 19 years old. In the 1960 World Series, as a 23 year-old second baseman, Bill Mazeroski was something of the unexpected and improbable hero. A second baseman and a .250 average as a hitter, Mazeroski was not your everyday, big-guy power hitter – not the Babe Ruth type expected to hit the ball out of the park. That year, in fact, Bill Mazeroski had 11 home runs – not bad for a second baseman, yet still not a total that would put fear into opposing pitchers.  Bill Mazeroski on his 74th birthday at September 2010 dedication of his statue at PNC Park in Pittsburgh, PA. When his 17-year career ended in 1972, Bill Mazeroski held the major league records for most double plays in a season and most double plays in a career. His Pirate numeral, No. 9, was retired in 1987. He was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2001. A street outside PNC Park in Pittsburgh is named Mazeroski Way, and a statue commemorating his famous 1960 World Series home run, was installed outside the Park in early September 2010. Mazeroski, then 74, spoke at the unveiling. His statue joined three others arrayed around the outside of the Pittsburgh ball park – one each for Pirate greats Honus Wagner, Roberto Clemente and Willie Stargell. |

The Celebration

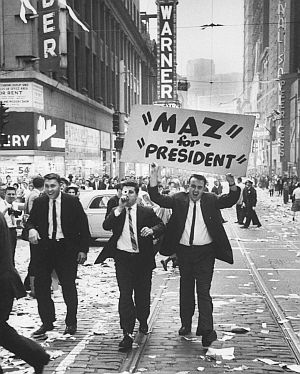

October 13, 1960: Downtown Pittsburgh, PA erupted in a prolonged celebration after Pirates won the World Series.

Life magazine, reporting on the celebration in a later edition, also noted the action following the victory: “… For the next 12 hours, Pittsburgh seethed in celebration for the team that should have lost but wouldn’t. The people felt and uncontrollable urge to let go – and loud. Automobile horns began a non-stop honking and attics were ransacked for whistles, tubas, and Halloween noisemakers. The hordes converged on downtown Pittsburgh where paper hurled from office windows had bogged down trolley cars. Snake dancers bearing sings torn from Forbes Field and beer bottled added to the traffic snarl….” By 9.pm. that evening, bridges and tunnels leading into the city had been closed, and downtown hotels were barring those without a room key from entering their lobbies.

October 14th, 1960: Pittsburgh Post-Gazette published a “souvenir edition” with its comprehensive coverage of the Pittsburgh Pirate victory in the 1960 World Series. Click for headlines collection.

Also in the newspaper that day, for example, was one front-page story on the Kennedy-Nixon presidential TV debate from the previous night, as well as another on the bellicose departing words of visiting Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev still upset over the U-2 spying incident, calling Eisenhower a liar and saying, “If you want war, you’ll get war.”

Still, in Pittsburgh at least, the main topic of the day on the 14th of October 1960 was that the Pittsburgh Pirates were the world champions of baseball. And as another Post-Gazette header and part “dig line” put it – meant no doubt to press salt into the wounds of those who thought the Pirates had no chance against the high-and-mighty Yankees – “We Had ‘Em All The Way.”

Bill Mazeroski had his own headline that day, of course. But also, further down in the sub-headline reporting, there was also mention of the Pirate’s Hal Smith as a key player in the team’s come-from-behind rally: “Five Run Rally in Eighth Inning Breaks Yank Lead as Smith Brings in 3 Runs With 4-Bagger.” The front-page photos featured Pirate manager Danny Murtaugh celebrating with hero Mazeroski and another with Pirates owner John W. Galbreath and general manager Joe L. Brown in a happy embrace.

Oct 1960: Pennsylvania Governor and former Pittsburgh mayor David Lawrence reads the good news. Click for related book.

Lawrence, who served as the 37th Governor of Pennsylvania from 1959 to 1963, was also mayor of Pittsburgh from 1946 through 1959. Lawrence was born into a working-class Irish-Catholic family in the Golden Triangle neighborhood of Pittsburgh and worked his way up the ladder in Pennsylvania politics. As of this writing, he is the only mayor of Pittsburgh to be elected Governor of Pennsylvania. He was a life-long Pirate fan and holder of a 1960 season ticket.

Bill Mazeroski at his 2nd base position in a later 1970 photo with the Forbes Field outfield wall behind him.

The 1960 World Series, meanwhile, left behind a few distinctions and records that still stand today. First, the Mazeroski home run is one of a kind – so far. As of this writing, it is the only walk-off, World Series winning, Game 7 home run in baseball history. Another World Series winning home run occurred in the 1993 World Series when Joe Carter of the Toronto Blue Jays hit one to end the Series, beating the Philadelphia Phillies. But that one came in a Game 6. In terms of championship home runs generally, there is only one other home run in 20th century baseball history that might be considered in a comparable dramatic vein to Mazeroski’s – that being the famous Bobby Thompson home run of October 3rd, 1951. Thomson’s homer came in the decisive Game 3 of a three-game playoff series that year to decide the National League pennant winner. The Brooklyn Dodgers and the New York Giants finished in a tie that year, and played at the Polo Grounds in New York for their decisive Game 3. In the bottom of the ninth inning, with two out and two Giant runners on base and Brooklyn leading 4-to-2, the Giants’ Bobby Thomson hit a 3-run home run to left field that won the game and the pennant for the Giants, 5-to-4. And a wild hysteria at the Polo Grounds then followed.

Another anomaly of the 1960 World Series is that the Most Valuable Player (MVP) award went to a player from the losing team — second baseman Bobby Richardson of the New York Yankees. Richardson had a good series — 11 hits for 30 at bats, hitting at .367, with 2 doubles, 2 triples, a grand slam home run, 8 runs scored, and 12 RBIs. Still, it’s the only time that a World Series MVP award has gone to a player on the losing team. And finally, in Game 7 of the 1960 World Series – that wild game with 19 total runs, 23 hits, four lead changes and five home runs – there were no strikeouts; not one, also a record for World Series play that still stands. Some fans and sportswriters mark Game 7 as one of the greatest World Series games ever.

Mickey Mantle – #7, “safe” at first – was said to have made a nifty move to avoid the tag of Rocky Nelson on a key 9th inning play when Yogi Berra, #8, grounded out.

What Ifs? The lore of the 1960 World Series lives on, in any case. As with all of baseball, when great games and great plays are recalled, there are always varied opinions, second guesses, and “what ifs.” And so it is with the 1960 World Series: “What if Whitey Ford had been the Yankee starter in Game 1 and had a chance for three wins in the Series?” Or – “What if Mantle had been tagged out by Nelson at first base in the top of the 9th when there were two outs with the Pirates ahead, 9-8?” Or – “What if that ground ball to Tony Kubek hadn’t taken a bad hop, with him making a double play instead of being injured and leaving two Pirates on base with no outs?” Some of those who played the game remember it too, and also have their opinions. “I still think we outplayed them,” said the Yankees’ Whitey Ford in a 2008 New York Times article on the 1960 Series. “We just felt we were a better team. And then to get beat by a second baseman who didn’t hit many home runs? I still can’t believe it.” Yet, in the World Series arithmetic that matters, the Pittsburgh Pirates won 4 games and the New York Yankees won 3 games. Casey Stengel, meanwhile, 70 years old that fall, was relieved of his command by Yankee management. Though in baseball history, Stengel remains one of the all-time best managers in terms of win-loss record.

Memory & Place. The 1960 surprise World Series win by the Pittsburgh Pirates has become more than merely one of baseball’s most famed moments. It is iconic, to be sure. But it is also of another time and place, and of a more innocent era. And for Pittsburgh fans who grew up in that time, and even those who watched the game on television in October of 1960, there is still a nostalgia and an attachment associated with that Series. For those who were alive at the moment, or even those schooled in the moment at countless American dinner tables, something about the photos of Maz running the bases – or even the stored memory of that image – just automatically brings up a feeling for that other time. “Somehow, it just did something to the city,” Mazeroski has said in recent years, “and they just can’t forget it.” And for natives of Pittsburgh – even if they’ve left town over the years for career or family reasons – there is also a special “sense of place” wrapped up in the memory – that of Forbes Field; a place that is partially there and not there, but still lingers in memory for tens of thousands still alive who had gone there as fans. And although Forbes Field was demolished in the 1970s, a portion of its left field wall has been preserved in the city — where, thanks to a Pittsburgh group named “The Game 7 Gang,” an annual gathering of fans and original radio broadcast of Game 7 occurs every October 13th. And also, by fluke it turns out, a film of Game 7 survives as well.

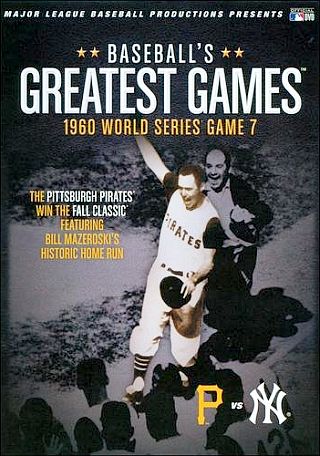

In 2010, Major League Baseball released the “Crosby Tapes” of Game 7 of the 1960 World Series as a DVD. Click for DVD.

Crosby Treasure

In 1960, neither the major TV networks nor local TV stations generally preserved telecasts of sporting events. In most cases, these telecasts were taped over and used for other shows and broadcasts. As a result, no TV film of the first six games of the 1960 World Series is known to exist. However, one happy exception is a remaining black-and-white “kinescope” of the entire telecast of Game 7 (kinescopes were tapes that were filmed from a video monitor, a common practice in the 1950s). The Game 7 kinescope was discovered nearly fifty years after the fact, in December 2009, quite by accident. The film was found in a wine cellar in the Hillsborough, California home of famous singer and Pittsburgh Pirate part owner, Bing Crosby.

Crosby became a part owner of the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1946 and remained an owner until his death in 1977. He was an enthusiastic supporter of the team, and also figured in the recruitment of one the team’s 1960 stars – pitcher Vernon Law. In 1948, Crosby made a telephone call to Law’s mother saying “I’d like you know, Mrs. Law, that we’d like to have your son, Vernon, pitch for the Pittsburgh Pirates.” And that call apparently made the difference, as Vernon, who had been more of a football prospect in the Boise area of Idaho as a high school athlete, signed with Pirates. “I guess you could say that Crosby’s telephone call was the final straw in our family decision that I’d sign with the Pirates,” he later explained to a reporter. “It sure thrilled my mother.”

1948: Bing Crosby at right with Pittsburgh Pirate manager Billy Meyer.

The Crosby estate negotiated a deal with Major League Baseball (MLB) for the use of the film for broadcast and conversion to DVDs. In November 2010, an exclusive screening of the film was held in Pittsburgh with some of the game’s participants in attendance. An audience of some 1,300 came out for premiere at the Byham Theater in downtown Pittsburgh – including eight members of the Pirates’ championship team and Bobby Richardson of the Yankees. (Mazeroski , however, was ill at the time).

Hal Smith being greeted by Dick Groat and Roberto Clemente for his 3-run home run, Game 7, 1960 World Series.

One poignant moment during the MLB screening of the Game 7 film occurred when the film showed Hal Smith’s key 8th inning, 3-run home run, as Smith, then 79, was in attendance. Smith – whose World Series homer gave the Bucs a 9-to-7 lead at the time but has always been overshadowed by the more dramatic Mazeroski homer – was given a standing ovation at the screening, not only from the fans in attendance, but from his fellow teammates as well.

Some baseball statisticians, meanwhile, have crunched the numbers on famous World Series home runs, and they conclude that Smith’s is one of the most important of all World Series homers, and statistically more important that Mazeroski’s in that it gave the Pirates an edge to win the game and the Series.

As ESPN’s Alok Pattani has reported, Smith’s home run “took the Pirates from having a 30 percent chance to win the game before the home run to being more than 90 percent favorites” to win the game (and the Series) after his home run — which they did.

Still, “the Mazeroski moment” carried the day in that October of 1960, and it lives on for the ages. For it was Mazeroski’s winning run that crossed the plate in the final Game 7 tally of 10-to-9, sending Pittsburgh into a frenzy. Yet Mazeroski himself – always humble in his much-feted heroic moment – has said many times, that his contribution was only one of many others in that game and in the 1960 World Series that resulted in Pittsburgh’s victory.

New Eras Ahead

The year 1960 was also something of an important demarcation – for sport, culture, and politics. In baseball, this was the last season of the 16-team professional structure – when the National and American baseball leagues each had eight teams. Expansion teams began to be added in 1961 and 1962. Nor were there Divisional or Championship Series playoffs in baseball then, only the regular season pennant races in each league and the World Series itself.

And beyond baseball, a few weeks following the 1960 World Series, the nation elected a new president, John F. Kennedy, who promised “a new frontier” and changes ahead. And so began not only a more modern era of government and politics, but also culture-wide changes in thinking, business, and personal style.

For additional stories on baseball, please visit the “Baseball Stories” topics page or go to the “Annals of Sports” page for sports stories generally. Thanks for visiting – and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research and writing at this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

____________________________________

|

Please Support Thank You |

Date Posted: 20 October 2014

Last Update: 13 October 2020

Comments to: jdoyle@pophistorydig.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “The Mazeroski Moment: 1960 World Series,”

PopHistoryDig.com, October 20, 2014.

____________________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

NY Daily News front-page headline for October 14, 1960, featured Kennedy-Nixon TV debate differences along with photo of Mazeroski home run celebration. |

Historic marker at the former site of Forbes Field in the Oakland section of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. |

Bill Mazeroski World Series statue shown against Pittsburgh skyline along the Allegheny River at PNC Park. |

John Drebinger, “Series Pitching: Bucs Have Edge; Law, Friend, Mizell Rated Over Yanks for Short Haul,” New York Times, October 3, 1960.

Roy Terrel, “Beat ‘Em, Bucs,” Sports Illus- trated, October 3, 1960.

United Press International (UPI), “Crosby’s Phone Call Sold Vernon Law On Pirates,” Milwaukee Journal, October 4, 1960, p. 2.

Louis Effrat, “Yanks 7-5 Choice To Capture Title; Odds Even on Opening Game — Pirates Calmly Study Reports on Bombers,” New York Times, October 4, 1960.

John Drebinger, “Pirates No Match in the Number of Distance Hitters; Bombers’ Attack Is Strong From Both Sides of Plate,” New York Times, October 4, 1960.

Roy Terrell, “Seven Bold Bucs” Sports Illus- trated, October 10, 1960.

“Two Inside Slants on the Big Series,” Life magazine: 1.) Jim Brosnan, “A Pitcher-Author Writes His ‘Book’ on The Pirates,” and, 2.) Ted Williams, “The Greatest Hitter of Our Day Respects Yankee Power and Casey,” Life, October 10, 1960, pp. 168-169+

“1960 World Series,” Baseball Almanac.com.

“1960 World Series,” Wikipedia.org.

“1960 World Series,” Baseball-Reference .com.

Reprint Series & Interactive Features, 1960 World Series Stories, Games 1-7, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, October 2010.

Jack Hernon, “Game One: Bucs Top Yanks in Opener, Pirates 6, Yankees 4 — Maz’s HR Nets Two Vital Runs, Law Earns Win,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette (Reprint Series), October 10, 2010.

Jack Hernon, “Game Two: Pirate Second Victory Slightly Delayed / Beat ‘Em Bucs, Next Time! Yankees 16, Pirates 3 — Yanks Clobber Pirates, Rout 6 Pitchers,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette (Reprint Series), October 10, 2010.

Roy Terrell, “The Knife And The Hammer,” Sports Illustrated, October 17, 1960.

Roy Terrell, “It Went All The Way!,” Sports Illustrated, October 24, 1960.

“The Bucs Heist Series and The Lid Blows Off: Implausible Series Ends With a Preposterous Civic Binge,” Life, October 24, 1960, pp. 32-35.

Pittsburgh Pirates, 1961 Yearbook (includes 1960 World Series summary, box scores, etc.).

Terry Chay, “Forbes Field Forever,” Terry Chay.com, April 14, 2006.

Sean D. Hamill, “In 1960, A Series to Remember (or Forget),” New York Times, June 24, 2008.

Jim Reisler, The Best Game Ever: Pirates vs. Yankees, October 13, 1960, De Capo Press, February 2009, Paperback, 336 pp.

Anne Madarasz, “Sports History: Field of Dreams,” Pittsburgh Sports Report, June 2009

“The One That Got Away,” MLBblogs.com, October 14, 2009.

“Forbes Field (1909-1970),” BrooklineCon- nection.com.

“Forbes Field: A Century of Memories,” Senator John Heinz History Center, Pittsburgh, PA, June 27-Feb. 22, 2010.

John Moody, Kiss It Good-Bye: The Mystery, The Mormon, and the Moral of the 1960 Pittsburgh Pirates, Shadow Mountain, March 2010, Hardback, 350 pp.

Rick Cushing, 1960 Pittsburgh Pirates – Day by Day: A Special Season, An Extraordinary World Series, March 2010, Paperback, Dorrance Publishing, 432 pp.

Robert Dvorchak, “1960 Pirates: Where Are They Now?,” Black & Gold, Sunday, April 4, 2010, at

Robert Dvorchak, “Pirates’ 1960 Champs ‘A Team of Destiny’; On 50th Anniversary, Team Remembered as Much More Than Just Maz,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Sunday, April 4, 2010.

Alan Robinson, Associated Press, “Pirates Honor Mazeroski With Statue of Famous HR Against Yankees,” New York Post, September 5, 2010.

Richard Sandomir, “In Bing Crosby’s Wine Cellar, Vintage Baseball,” New York Times, September 23, 2010.

Richard Sandomir, “50 Years Later, a Slide Still Confounds” [re: Mickey Mantle on first base], New York Times, September 30, 2010.

David Schoenfield, “The Greatest Game Ever Played,” ESPN.com, October 13, 2010.

Alok Pattani, “Ranking Most Valuable World Series HRs,” ESPN.com, October, 29, 2010.

Mike Dodd, “Pirates Heroes Dust off Reel Classic Game 7 of the 1960 Series,” USA Today, Updated November 16,2010.

Ray Kienzl, “Maz Hoped It Would Go for HR; Sock Touches Off Long Celebration,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, October 13, 2010.

Al Gioia, “Our Town Goes Wild Over Pirate Victory; Crowds Yell, Firecrackers Boom, Air Raid Sirens Shriek, Confetti Rains, Church Bells Ring,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, October 13, 2010.

Clifton Blue Parker and Bill Nowlin (eds), Sweet ’60: The 1960 Pittsburgh Pirates, Society for American Baseball Research, 2013.

Tom Conmy, “Hal Smith: Bucs Bridesmaid, World Series Hero,” BehindTheBag.net, February 17, 2013.

Mila Sanina, “1960: ‘Dreaming of the World Series…Too Soon, You Say?’,” The Digs: Pittsburgh Post Gazette, October 9, 2013.

Bob Hurte, “Bill Mazeroski,” SABR.org (Society for American Baseball Research), September 2014.

Mel Allen Call & TV Video of 1960 Bill Mazeroski Home Run, PittsburghPost-Gazette.com.

_____________________________________

This is a painting of the black-and-white photograph used at the top of this article. It is the work of Graig Kreindler, and there are more of these “golden era” baseball paintings at his website, http://graigkreindler.com/

____________________________