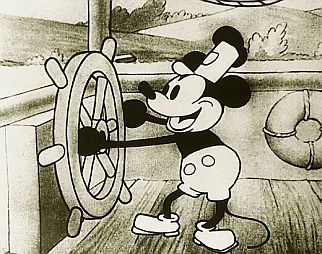

Mickey Mouse was born in 1928, shown here in the film short, 'Steamboat Willie,' which debuted in New York. Click for DVD.

Along with partner Ub Iwerks, Disney had bounced around Hollywood and New York with some fits and starts, but no real major successes. Then in 1928 the two artists tried a new mouse character in place of an earlier Disney rabbit named Oswald, which Universal Studios claimed as their property. Thereafter, Disney vowed to secure his inventions, and it was then that he and his partner created the new mouse character.

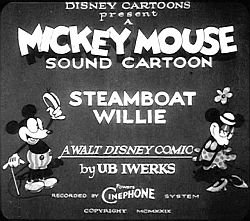

Disney first thought to name his mouse “Mortimer,” but his wife Lillian suggested “Mickey” to his and history’s good fortune. Disney and Iwerks first introduced the Mickey Mouse cartoon character to the world in a May 1928 silent short titled Plane Crazy. That first cartoon was not a success, as Disney then lacked the needed distribution channels. But the next cartoon released in November 1928, Steamboat Willie, was a success. A short film just under 8 minutes as most then were, Steamboat Willie was the first to synchronize sound with movement and character — in this case Mickey whistling as he piloted his boat.

Steamboat Willie met with great success among the movie-going public. Disney’s earlier Mickey cartoons were then reissued with sound, followed by a dozen new ones — all issued in 1929.Walt Disney Productions was formed that year as well, and the company began turning out the short, animated films — “shorts,” as they were called — on a regular basis.

By 1932, Disney received a special Academy Award for the creation of Mickey Mouse, whose series was moved into color by 1935. Along the way, a cast of supporting animated characters were introduced in the Mickey films — Minnie Mouse, Horace Horsecollar, Clarabelle Cow, Donald Duck, Goofy, Pluto and others.

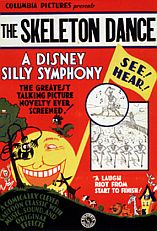

Alongside the Mickey Mouse series, Disney also produced short cartoon films called the “Silly Symphonies” that were, according to the Walt Disney Family Museum, “more daring, quirkier and more diverse” than anything in the Mickey Mouse series. Some of these films were also highly artistic, and helped bring notice to Disney & Co. on that level as well. Among the most famous and remembered of the Silly Symphonies are: The Skeleton Dance, Flowers and Trees, The Old Mill, and Three Little Pigs. Disney’s animated characters populated these shorts as well, including — Donald Duck, the Big Bad Wolf, Elmer Elephant, and Max Hare, among others. Still, it was Mickey Mouse who became Disney’s star, and it turned out, well beyond the movie houses.Mickey “Multiplier”

America in the 1930s, however, was not in jovial state. Following the 1929 stock market crash, the economy deteriorated steadily. Through 1932, Herbert Hoover was president and he did not believe the federal government should become directly involved in fixing the economy. In 1933, shortly after President Roosevelt was elected and inaugurated, “New Deal” programs sought to stimulate the economy and provide jobs. Still, there was a long road ahead. Unemployment by then had reached historic levels, as the nation’s financial system teetered on the edge of collapse. In the midst of this, the country looked for any signs of optimism, recovery, and prosperity ahead. And some of that came from a surprising quarter — from Walt Disney’s animated creations. The short Mickey Mouse cartoons had become a hit with movie goers of all ages, and new films of Mickey and his friends were being churned out by Disney and his artists at a rate of about one per month. But most importantly for the 1930s, the cartoons were proving to be a business stimulus.

By 1935 Mickey Mouse and his friends had become a merchandising phenomenon. No less a cheerleader than the New York Times chronicled Mickey and Disney’s rising “multiplier role” in an otherwise bleak national economy. “New applause is heard for Mickey Mouse. . .”, wrote H.L. Robbins in the New York Times Magazine of March 1935.“The fresh cheering is for Mickey the Big Business Man, the world’s super-salesman. He finds work for jobless folk. He lifts corporations out of bank- ruptcy…”

– The New York Times

March 1935 “The fresh cheering is for Mickey the Big Business Man, the world’s super-salesman. He finds work for jobless folk. He lifts corporations out of bankruptcy. Wherever he scampers, here or overseas, the sun of prosperity breaks through the clouds.”

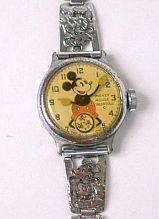

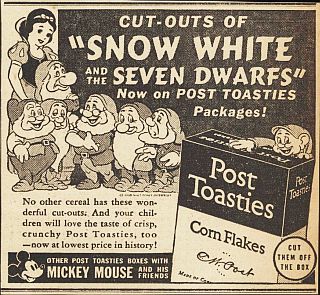

Indeed, through the 1930s, Mickey Mouse merchandising exploded; hundreds of products were available across the country and around the world. There were Mickey Mouse phonographs and radios; Mickey Mouse wrist-watches, satchels and briefcases. There was also Mickey Mouse soap, candy, playing-cards, hairbrushes, chinaware, alarm clocks, hot-water bottles, table covers and napkins, Mickey Mouse biscuits and dairy, Mickey Mouse book-ends, and of course, Mickey Mouse music. At least four publishers were then selling Mickey Mouse books, one of which in1934 had sold 2.4 million copies. Mickey Mouse pencils, paper, school notebooks, and tablets were sold by the million as well. Food-product companies “hired” Mickey to sell breakfast cereal and also used Madison Avenue advertising to tout their new friend. In England there was Mickey Mouse marmalade. New York’s Fifth Avenue sold Mickey Mouse charms and bracelets, some in gold and platinum, and a few with diamonds. A Cartier diamond bracelet sold for $1,200. Some department stores used Mickey Mouse window displays, which could cost $25,000 for a single display. By 1934, Mickey merchandise was earning about $600,000 a year.

Screenshot of title card & credits for Disney's 1928 Mickey Mouse cartoon, "Steamboat Willie."

Good Timing

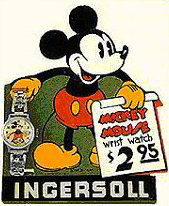

The Mickey Mouse Watch was first made in mid-1933 by the Ingersoll-Waterbury Clock Company of Waterbury, Connecticut. The company’s financial condition at the time was not good, but the Mickey Mouse watch was offered for sale at an expensive $3.25, or about $52.00 in today’s money. Still, the response to the watch was somewhat favorable, even at that price. However, the market improved when Ingersoll-Waterbury reduced the price to $2.95, using some advertising to tout the new price (see below). In fact, the watch did well enough for Ingersoll-Waterbury that it is credited with helping to keep the company afloat during the Depression. Ingersoll-Waterbury became “Timex” in the 1960s, continuing to produce Mickey and Minnie Mouse watches. Other companies have since become involved in making Mickey Mouse watches including Seiko, Fossil, Colibri, and Disney Time Works.

Mickey wrist watch ad, 1930s.

As Mickey Mouse products were having a positive effect throughout the economy of the 1930s, the bigger enterprise of Walt Disney Productions — and what would become its mainstay business and product well-spring for years to come — would be its feature-length animated motion pictures. And that too, began in the 1930s.

Movie poster for Walt Disney’s first feature-length animated film, 'Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs,' 1937. Click for poster.

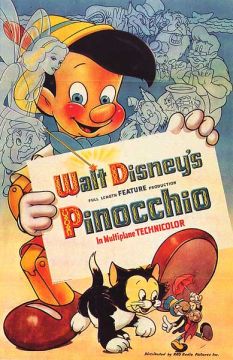

Mickey and Disney’s fortunes in the 1930s had risen primarily on the basis of its nine-minute cartoons. Granted, there were a number of them running in theaters regularly through the mid-1930s. But no major motion picture by Disney then existed. The first would come in late 1937 when Disney released a full-length animated film, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. Many wondered whether Disney would make money with so extravagant a production as Snow White, which took years to make and cost $2 million to produce — then an enormous expenditure. For a time, in fact, Snow White was dubbed “Disney’s Folly” — but not for long.

When it opened in Hollywood at the Carthay Circle Theater on December 21, 1937, one trade paper noted that “a picture capable of making happy kiddies out of the bluebloods of Hollywood… will captivate the plain population as perhaps no other motion picture ever has or will.” And it did.

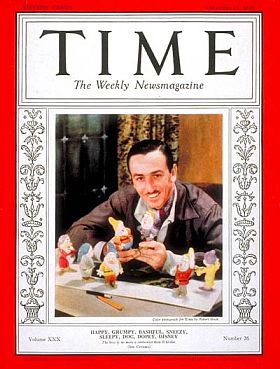

isney on the cover of Time magazine, December 27, 1937, along with his seven new friends.

By the spring of 1939, Snow White had earned an estimated worldwide gross of $10 million, then a sizeable fortune. But Snow White had also broken a barrier, going beyond cartoon shorts. No longer would animation be limited to a minor supporting role or one-reel shorts. Snow White was a clear signal that animation could become a major new business, as Disney’s subsequent films would prove. The success of Snow White, says the Disney Family Museum “was more than a gratifying success story — it was the gateway to a practically unlimited future.”

Even in 1938, Disney’s success was being viewed by some observers as a sign of something much bigger. By May 1938, the film had become such a merchandising success that the New York Times celebrated its economic impact, using the term “industrialized fantasy” in a positive way, touting the new business not only as a positive contributor to climbing out of the 1938 recession, but also as a promising new industry. Here’s the complete May 2, 1938 New York Times editorial: “Prosperity Out of Fantasy”:

|

“Prosperity Out of Fantasy” It is said that what America needs to swing it out of the present economic tailspin is a new industry. Many things just over the horizon, such as television, air-conditioning in the home and flivver airplanes, have been suggested. But none of them seems yet to have materialized in terms of wages and heavy sales. Would it be ridiculous to suggest that industrialized fantasy may prove to be the answer? Industrialized fantasy sounds like something extremely complex. Yet it is quite simple. Walt Disney’s picture-play “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” is an excellent example. Here is something manufactured out of practically nothing except some paint pots and a few tons of imagination. In this country imagination is supposed to be a commodity produced in unlimited quantities.“Figments of Disney’s imagination have already sold more than $2,000, 000 worth of toys since the first of the year.” If it can be turned out as an article of commerce which the public will readily buy, then prosperity should be-well, just around the corner, anyway. The Disney picture cost about $2,000,000 to produce. To be sure, it gave employment to no flesh-and-blood actors, human attributes being confined to voices on the sound tracks. But it kept a small army of artists, animators and gag men busy for many months. And from all reports it will not only return more than this investment to Mr. Disney, but is showering fortune on every playhouse that shows it. Dopey, Grumpy and their fellow-dwarfs, despite the fact that they get no wages themselves, have been the most valiant miners and sappers against recession whom the moving picture magnates have hired this year. No matter what business may have been in most theaters, the exhibitors of “Snow White” have not had to layoff a single dwarf. Moreover, the picture has virtually developed a new industry from its by-products. Figments of Disney’s imagination have already sold more than $2,000,000 worth of toys since the first of the year. Since January, says Kay Kamen, Mr. Disney’s representative here, 117 toy manufacturers have been licensed to use characters from “Snow White.” The only thing in the picture that the public doesn’t seem to crave is poisoned apples. One factory in Akron, Ohio, which makes little rubber dwarfs, has been running twenty-four hours a day, while many of the other rubber factories are closed. Dopey and Grumpy are putting men to work in paint shops, box factories, silica mines, stone quarries and mills all over the map. Wherever they turn up, prosperity begins to radiate. “Snow White” is Disney’s first full-length picture. What is going to happen when he really gets into his stride? Industrialized fantasy? It should be industrially fantastic. |

One of many ‘Walt and Mickey’ statues found throughout the Disney empire today. Click for desk-size replica/ornament.

New Kind of Commerce

Disney of the 1930s, of course, pales beside the Disney of today. But even in those early years, Disney’s “entertainments” were having a decided impact on the larger world. The Disney of the 1930s was not only helping to buoy a shaky American economy, it was also helping to build the foundation of something new — a global entertainment economy. As time would tell, this new kind of commerce would reverberate in jobs, finance, balance-of-trade and more, becoming a much bigger part of the national and global economies. It would also permeate popular culture and politics in new and more powerful ways.

Readers of this story may also find other business & entertainment history at this website of interest, including the following: “They Go To Graceland” (story about the big business that is Elvis Presley’s Graceland estate near Memphis); “Dempsey vs. Carpentier, July 1921” (early radio & rise of sports entertainment biz); “Basketball Dollars, NCAA-2009” (sports & the ‘entertainment economy’); “Stones Gather Dollars, 1989-2008” (Rolling Stones & rise of much bigger rock concert biz); “Empire Newhouse, 1920s-2012” (Newhouse publishing & media history, from newspapers and magazines to Reddit.com); and “Disney’s Movie Vault, 1984-1998.”

Thanks for visiting – and if you like what you find here please make a donation to help support the research and writing at this website. Thank you. — Jack Doyle.

_________________________________

|

Please Support Thank You |

Date Posted: 31 July 2008

Last Update: 26 April 2018

Comments to: jdoyle@pophistorydig.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Disney Dollars, 1930s,”

PopHistoryDig.com, July 31, 2008.

_____________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

1938 newspaper ad for Snow White & The Seven Dwarfs cut-outs on “Post Toasties” cereal box.

L. H. Robbins, “Mickey Mouse Emerges as Economist,” The New York Times Magazine, March 10, 1935.

“Mouse & Man,” Time (cover story), Monday, December 27, 1937.

“Prosperity Out of Fantasy,” Editorial on Disney’s Snow White movie, Topics of the Times, New York Times, May 2, 1938.

Charles Solomon, “The Golden Age of Mickey Mouse,” The Walt Disney Family Museum.

“Walt Disney” and “Mickey Mouse,” Wiki-pedia.org.

“Ingersoll Mickey Watch (1935) & Lionel Mickey Mouse Handcar (1935),” Cowan Collection: Animation, Tuesday, May 13, 2008.

“A Mickey Mouse Watch History: An Introduction,” formerly at: Mickey.Mouse-Watches.com (now an incorrect/dead link; not found elsewhere).

J.B. Kaufman, “The Success of ‘Snow White’,” The Walt Disney Family Museum.

Derek Thompson, “In 1938, The New York Times Thought Disney Toys Would Save the U.S. Economy,” The Atlantic.com, July 7, 2014.

__________________________________________________