In the mid-1980s, Dow Chemical, then one of the world’s largest chemical companies, was in the midst of a public advertising campaign designed to enhance its corporate image. Dow had been through a rough patch of bad press and corporate troubles stretching from the mid-1960s through the early-1980s — including the likes of napalm, Agent Orange, and dioxin pollution — which had tarnished its reputation. So after a time of corporate introspection and “let’s-make-a-change” agreement, a $50 million-plus public relations and advertising campaign was fashioned to fix the bad optics. More on the history of Dow’s troubles, past and present, in a moment. But first, a few sample TV ads from Dow’s mid-1980s corporate makeover campaign.

In this ad, the young woman in cap and gown, shown waiting to receive her diploma, recalls how “Mom made me clean my plate ’cause there were places where kids were starving.” But now, as a college graduate, she was “about to walk into a Dow laboratory to work on new ways to help grow more and better grain for those kids who so desperately need it.” She leaves the stage with big smile and the look of determination, having already remarked, “can’t wait” to get into her work, as the chorus chimes in, “Dow Lets You Do Great Things.”

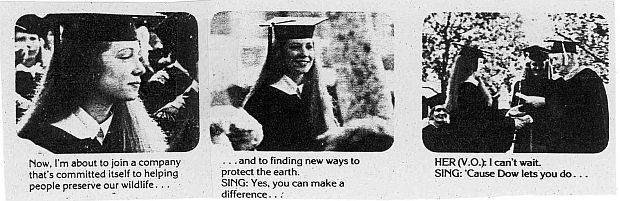

A similar college-grad TV ad with a somewhat different message, shows the young woman in cap in gown, this one saying: “I’m about to join a company that’s committed itself to helping people and preserving wildlife… and to finding new ways to protect the earth” Cue the music: “Yes, you can make a difference…” Cut to graduate with her diploma in hand, again saying, “I can’t wait.” as the chorus rises with the theme, …“`cause Dow, Lets You Do Great Things.”

Portion of a story board showing sequence of one of Dow’s “college grad” TV ads, this one focused on the grad choosing “wildlife and the environment” as her career choice at Dow.

Other ads in the series also depicted young people making career choices with Dow, ads which also trumpeted the presumably good ends to which Dow research and Dow businesses were engaged. A TV ad of this variety, shows a young couple on a campus-like setting walking together and talking about the guy’s career options after a Dow job interview. As they walk away in a brief rain shower, he tells his partner, who asks what job he’s decided to take, that he intends “to go with that subsidiary of Dow,” adding: “I could actually be helping high-risk heart patients.” Cue the music: “Dow Lets You Do Great Things,” as the rain stops and the sun comes out.

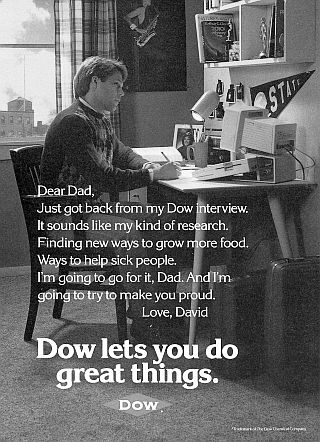

One of Dow Chemical's mid-1980s ads appearing in print.

In this Dow ad, a college student at his desk in a dormitory room, writing home to his father explains: “Dear Dad… Just got back from my Dow interview. It sounds like my kind of research. Finding new ways to grow more food. Ways to cure sick people. I’m going to go for it, Dad. And I’m going to try to make you proud. Love David.”

In any case, by the mid-1980s, and after some years of bad press, Dow needed an image makeover. It was also becoming somewhat more of a consumer products company, putting itself more directly in the public eye. So it embarked on this multi-million dollar public relations campaign, using the upbeat theme “Dow Lets You Do Great Things,” to help turn things around.

Yet the imagery of happy college students lining up to take Dow jobs to help further the company’s business interests around the world wasn’t exactly how Dow was perceived during its more turbulent times.

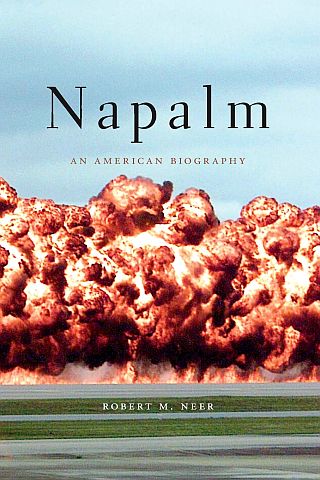

Robert Neer’s 2013 book, “Napalm: An American Biography,” Belknap Press (Harvard University imprint), 352pp. Click for copy.

1960s

Dow & Napalm

In 1965, Dow Chemical Co. was awarded a contract from the federal government to produce napalm for the U.S. military in the Vietnam War. Napalm is a jellied, lava-like incendiary bomb capable of especially horrific effects on people and the environment. During combustion, napalm sucks oxygen out of the air, generates large amounts of carbon monoxide, and can also cause firestorms. In the bombing area the air can become 20 percent or more carbon monoxide, as napalm partially combusts the oxygen, turning CO-2 (carbon dioxide) into CO (carbon monoxide). Burning at very high temperatures, it also adheres or sticks to its targets, burning through human skin to the bone, leaving disfigurement for those who survive being hit by napalm.

Napalm had previously been used in WWII and in Korea. But in the lush, vegetative regions of Vietnam, napalm was seen as an important military asset. General Earle Wheeler, chairman of the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff, explained that it helped penetrate dug-in Viet Cong and North Vietnamese positions, as the burning incendiary flowed into foxholes, tunnels, bunkers, drainage and irrigation ditches, and other improvised troop shelters. By comparison, Wheeler explained, conventional bombs were not as effective: “Napalm, by nature of its splashing and spreading, can get into such defensive positions. It’s also especially effective against antiaircraft positions, because normally the enemy digs a hole – …and puts his machine gun in that hole…. The napalm splashes in and incapacitates the crew and sometimes destroys the weapon.”

1960s photo of a napalm bombing in South Vietnam, showing its “splash-and-spread” effects.

For Dow Chemical, from a production standpoint, napalm was relatively easy to make – mixing gasoline, benzene, and polystyrene. With a small group of workers, Dow set up a modest production operation at its Torrance, California plastics plant combining the three chemical ingredients, and proceeded to fulfill its napalm contracts over the next four years. Napalm was not a big business for Dow, and according to one estimate, the company never made more than $5 million worth (or about $45 million in 2022) in any one year. Yet it became an infamous product for Dow. As reports of its use in the war reached the American public, however, the company was thrust into the public limelight as never before.

Napalm became a focus of 1960s anti-war activists, and Dow was cast as a government handmaiden in the war and a target of protest. One of the first protests aimed at Dow, occurred in late May 1966 at the company’s New York city headquarters at Rockefeller Center. A Sunday, May 29, 1966 headline in the New York Times, noted: “Dow Chemical Office Picketed For Its Manufacture of Napalm.” Peace groups, including some 75 protestors from Citizens’ Campaign Against Napalm and Women Strike for Peace, handed out leaflets on the street. In their street taunts and protest literature, the demonstrators charged, “Napalm Burns Babies!” and other such slogans. They called on consumers to boycott Dow products such as Saran Wrap. Also in late May 1966 on the West Coast, a small group of protesters picketed Dow’s production plant in Torrance, California, calling on Dow to stop production.

May 1966. New York Times reporting on one of the early Dow protests over its napalm production.

Also in January 1967, Dr. Richard E. Perry, an American physician, wrote about napalm on his return from Vietnam in Redbook magazine, read largely by women: “I have been an orthopedic surgeon for a good number of years, with rather a wide range of medical experience. But nothing could have prepared me for my encounters with Vietnamese women and children burned by napalm. It was shocking and sickening, even for a physician, to see and smell the blackened flesh.” By then, the American public began to see images of the civilian casualties caused by napalm bombs on TV news reports.

1960s

College Protests

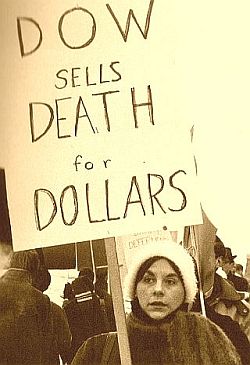

February 1967. Protester at Northern Illinois University (DeKalb, IL) objecting to Dow recruitment on campus. NIU.edu

Some of the first anti-Dow college demonstrations occurred in October 1966 at the Berkeley campus of the University of California and also at Wayne State University in Michigan.

In February 1967, when recruiters from Dow Chemical arrived at the Northern Illinois University Placement Office in DeKalb, Illinois, they were greeted by student demonstrators such as the one shown at right bearing protest signs with messages like “Dow Sells Death for Dollars.”

There were also pro-war demonstrations at Northern Illinois and other universities during those years, as well as some demonstrations favoring Dow recruitment on campus. But throughout the 1960s, the anti-war demonstrations would grow in numbers and frequency.

One major anti-Dow student protest that turned violent occurred at the University of Wisconsin’s main campus at Madison on October 18, 1967. Student protesters there tried to block Dow recruiters on campus, first as a peaceful sit-in, with hundreds of students filling a campus hall where Dow recruiters were scheduled to conduct interviews. But when the demonstrators failed to disperse, local police were called in and rioting erupted. As the officers forced protesters into an outdoor plaza tear gas was used.

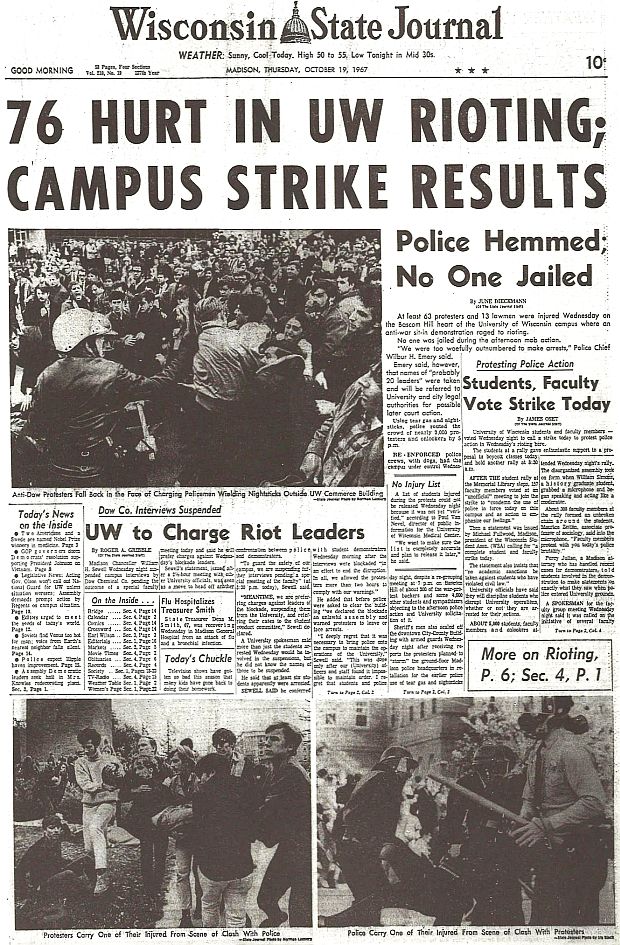

Wisconsin State Journal of Oct 19,1967chronicles campus protest at the University of Wisconsin with headlines & first photo caption noting: “Anti-Dow protesters fall back in the face of charging policemen wielding nightsticks outside UW Commerce Building.”

The Wisconsin State Journal of October 19,1967, shown above, chronicled the protest with a front-page headline, “76 Hurt in UW Rioting; Campus Strike Results.” A photo below the headline showing the confrontation between police and students, noted: “Anti-Dow protesters fall back in the face of charging policemen wielding nightsticks outside UW Commerce Building.” In the end, 47 students and 19 police officers were sent to the hospital. That evening at a mass meeting, students agreed to boycott classes.

One of the UW students at the protest was then freshman, David Maraniss, who would later become a Washington Post reporter and author of the 2003 book, They Marched Into Sunlight: War And Peace. America and Vietnam, October 1967 (also a source for a PBS documentary). His book juxtaposed the history of one military action then occurring in Vietnam with student protests occurring at the same time back home in Madison.Television news images of the violent confrontation at the University of Wisconsin were broadcast coast to coast, and by one account they triggered nearly 2,000 newspaper articles and editorials about Dow and napalm. The Wisconsin eruption also inspired the spread of Dow protests to other campuses.

Some activist faculty, such as Boston University historian, Howard Zinn, were also speaking out about the war. Zinn wrote a November 1967 article in The Spectator magazine titled, “Dow Shall Not Kill,” applauding efforts of student protestors to halt Dow recruitment on campuses, actions he lauded as justified civil disobedience against an unjust war.

One week after the Wisconsin protest, on October 25, 1967, a Dow recruiter at Harvard University was blocked, confronted, and questioned by protesting students before leaving the campus some hours later, while a parallel demonstration a few blocks away at Harvard Square sponsored by SDS and other groups, handed out leaflets with photos of napalmed-burned children urging readers “Don’t Buy Dow Products.”

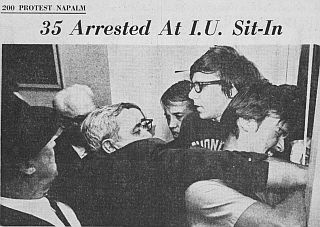

AP photo from Indianapolis Star story of Oct. 31, 1967, showing student protesters attempting to “sit-in” at a Dow Chemical recruitment session at Indiana University, Bloomington, IN. |

“Dow Protest Becomes Riot; Police Use Gas, Clubs on Crowd,” Spartan Daily (San Jose State College, CA), Nov. 21, 1967, p. 1. |

Nov. 30, 1967. New York University newspaper reporting that Dow would call off it recruitment after student pickets. |

Other campus protests over Dow and napalm in late 1967 occurred at colleges and universities all across the country – some requiring police actions, arrests, and/or later court cases.

On October 31, 1967, some 35 student protesters attempting a sit-in at a Dow recruitment session at Indiana University in Bloomington, Indiana were arrested.

On the West Coast, at San Jose State College, San Jose, California, a November 20th, 1967 Dow protest rally got out of hand as police used tear gas and clubs on demonstrators there, as reported by the college newspaper, The Spartan Daily.

On November 30, 1967, Dow called off its recruiting at New York University in New York city after some 250 students picketed two sites, as reported by NYU’s newspaper, Washington Square Journal.

At the University of Iowa in early December 1967 student protests were front-page news in the local and university newspapers: “Anti-Dow Rally Erupts at UI,” Iowa City Press-Citizen, Decem-ber 5, 1967. p. 1, and, “Protestors Lead Cops on Wild Race to the Tune of ‘Dow Must Go Now’,” The Daily Iowan, December 6, 1967, p. 1.

Among some of the anti-Dow and napalm protest placards appearing at the University of Iowa demonstrations were the following: “Napalm is Immoral,” “No to Napalm,” “Napalm is a Crime Against Humanity,” “Stop Dow Now,” and others – plus one guy cloaked in Grim Reaper garb with the message, “I Am Dow’s Only Recruit.”

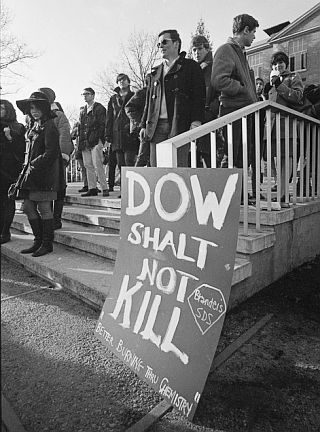

Also on December 6th, 1967 at Brandeis University in Waltham, MA, 150 students sat-in at the Administration Building to protest Dow recruiting on campus, while another 500 picketed outside. The university later agreed to the student demands, barring Dow recruiters from campus.

Additional student protests in 1967 over Dow’s production of napalm and/or its recruiters on campus occurred at the University of Maine, Marquette Univer-sity, UCLA, Northeastern University, the University of Chicago, Boston University, the University of Illinois, the University of Minnesota, and others. By the fall of 1967, the Dow protests were occurring so frequently — 133 campus demonstrations aimed at Dow recruiters in 1967 — that the company began publishing a newsletter titled “Napalm News” for key managers and campus recruiters to keep them informed of where protests might be expected. But 1967 was only the beginning.

Protest sign at December 6th, 1967 demonstration at Brandeis University in Waltham, MA.

Anti-Dow demonstrations over napalm were also held in 1968 at University of Wisconsin campuses in River Falls and La Crosse, Wisconsin.

On February 22nd, 1968, students, faculty and a Dow representative participated in an open forum at the University of Michigan on the moral responsibilities of napalm production.

On March 6th, 1968 more than 500 New York University students demonstrated against the reappearance of Dow recruiters on campus.

At Syracuse University in New York on March 12th, 1968, more than 100 students barricaded the administration building with benches, rope and wire to protest Dow recruitment on campus.

In the Spring of 1968, students at Stanford University organized a sit-in with demands that the college change recruitment policy to disallow Dow recruiters, later adopted when Stanford’s faculty voted not to support the administration.

On May 8th, 1968, over 400 protestors, including hundreds of students, protested Dow’s manufacture of napalm at the company’s annual shareholder’s meeting in Midland, Michigan.

In November 1968, students at Notre Dame organized a large-scale demonstration during several days of Dow recruitment interviews.

Photograph of a 1969 anti-Dow Chemical Company protest at the University of Michigan.

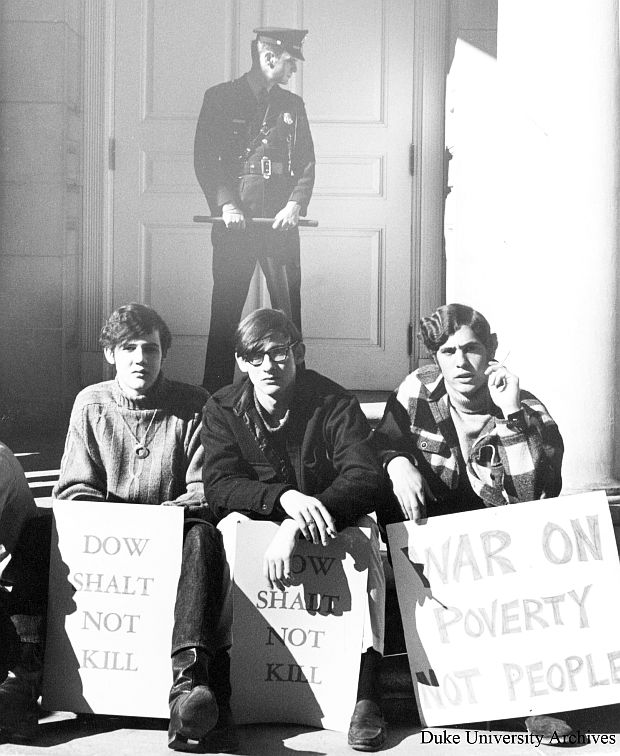

The following year, in February 1969, students at Rutgers University held a sit-in at the Newark, NJ campus in protest against university complicity with Dow and the war effort. At Duke University that same month, a Dow recruiter had been on campus but refused to answer questions about its production of napalm, resulting in a protest there. Also in 1969, students at the University of Washington occupied the Loew Hall Placement Center to block recruitment interviews by Dow, and at the University of Manitoba in Canada, students placed chains and locks across the doors for their “sit in” blocking Dow recruiters. Students and some faculty at the University of Saskatchewan also picketed Dow at the school’s placement office that year.

At Duke University in February 1969, a Dow recruiter had been on campus but refused to answer questions about its production of napalm, resulting in a protest there. Duke University Archives photo.

However, not all the Dow protests came from college students. In one notable Washington, D.C. protest, a number of clergy were involved. In late March 1969, a group of nine religious- affiliated protesters – later dubbed “the D.C. nine” – broke into the Washington offices of Dow Chemical, poured blood on furniture and records, and threw files out of a fourth floor window. Eight of the protesters were Catholics – three priests, two Jesuit candidates not yet ordained, a former priest, a nun, and a former nun.

Photograph of “the D.C. nine” religious-affiliated protesters who raided Dow’s D.C. office in March 1969, reported by Patrick McGrath, “Dow Office Attacked, Files Scattered,” National Catholic Reporter, April 2, 1969.

Dow’s shareholder meeting of May 7th, 1969 in Midland, Michigan was also the scene of 250 protestors, including students and religious leaders objecting to the company’s continued production of napalm. On November 18, 1969, police in riot gear broke up a peaceful protest against Dow recruiters at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana. A group of protesting students there – named the “Notre Dame Ten” – were suspended and expelled, with at least one faculty member resigning in protest.

By mid-November 1969, however, it was reported that Dow had stopped producing napalm for the government, as it was underbid by another company – although Dow officials at the time indicated they would bid again in the next contract round. But Dow never did produce napalm again for the U.S, military.

Perhaps the most significant legacy of Dow’s napalm association was that it pushed the company into the national limelight. At the outset of the 1960s, Dow was well known in its home state, Michigan, but it was fairly obscure elsewhere. Napalm and Vietnam changed that, making Dow “a household word” – and not in a good way – though some at Dow laid claim to the marketing maxim of “any notice is good notice.” While Dow stopped making napalm in 1969, it continued to be associated with napalm through the late 1980s. Nor did its exit from napalm production end Dow’s association with the Vietnam War. For Dow was also supplying another product to the U.S. military during the Vietnam War – a products known as Agent Orange.

Agent Orange

1962. Herbicidal defoliants being sprayed by U.S. military in Vietnam via “Operation Ranch Hand.” AP photo.

Dow Chemical became the largest of nine government contractors supplying the Agent Orange herbicide for the war. Dow eventually supplied an estimated one-third of the nearly 13 million gallons of Agent Orange the government used in Vietnam. By the mid-1960s, the Agent Orange concoction of 2,4,5-T and 2,4-D (both of which were then used separately in U.S. agriculture, utility corridors, and other applications) was being dumped by the planeload over thousands of acres in Vietnam. Yet, even as the U.S. military was beginning its Vietnam spraying in the early 1960s, back home, Rachel Carson was raising a lone voice of warning about pesticide toxicity with her 1962 book Silent Spring. Noting that 2,4-D and 2,4,5-T had become widely used agricultural herbicides, she reported that some early lab results indicated that negative health-effects were then beginning to appear. But also, as later learned, a trace lethal by-product, dioxin, was formed in the making of Agent Orange (which also occurs in the making of other chlorinated compounds), and it would be this contaminant that would become the major health-effects bad actor.

Peter Sills’ 2014 book, “Toxic War: The Story of Agent Orange,” Vanderbilt University Press, 296 pp. Click for copy.

Agent Orange, in fact, and the chemicals that comprised that mixture, along with dioxin, would generate decades of health effects controversy, numerous studies, warring scientists, Congressional hearings, lawsuits, some settlements, and continued fighting, not only in the U.S. and Vietnam, but also in New Zealand where the herbicides were produced by a Dow joint venture. One consolidated class action lawsuit brought on behalf of thousands of U.S. veterans against Dow and the six other manufacturers of Agent Orange was settled out-of-court in 1984 for $180 million dollars – over the objections of many Vietnam vets who felt betrayed, as the settlement fund expired in 1994. In 2004, Vietnamese citizens filed a multi-billion dollar class action suit against the chemical companies alleging that Agent Orange constituted chemical warfare under international law. That case was thrown out, with the court finding the chemicals had been intended for foliage, not humans, and so it wasn’t chemical warfare. Appeals all the way to the Supreme Court did not reverse the ruling (the Agent Orange story is a long and convoluted one, with numerous books on the subject, such as the one above and others noted in Sources below).

The lingering legacies of napalm and Agent Orange, plus the ongoing controversies, court challenges and EPA actions over the safety and continued use of 2,4-D and 2,4,5-T as agricultural herbicides, kept Dow Chemical in the news through the 1970s and 1980s. But Dow had other problems as well, some of which were first more local and regional, though in some cases, escalating to the national level as well – all of which figured into its corporate image problem. More on these in a moment.

|

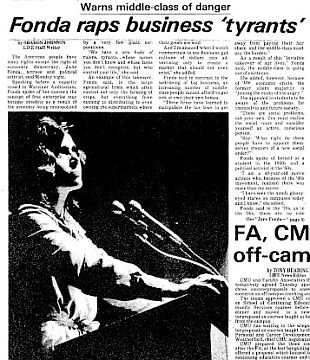

Fonda At CMU

“Jane Fonda Rowe” On October 10,1977, as the Dow Chemical Company was still in the midst of its toxic chemical troubles and corporate reputation problems, controversial activist and Hollywood actress, Jane Fonda, gave a speech at Central Michigan University (CMU) in Mount Pleasant, Michigan, about 30 miles from Dow headquarters at Midland.  ‘Central Michigan Life’ student newspaper reporting on Jane Fonda’s October 1977 speech at Central Michigan University. At the time, Fonda – then a widely known and controversial anti-war activist – was on a speaking tour helping to promote and raise funds for an organization she and her then husband, fellow activist and California politician, Tom Hayden, had created, the Campaign for Economic Democracy. Speaking before a capacity crowd at CMU’s Warriner Auditorium, Fonda offered that “the American people have many rights except the right of economic democracy.” The economy, she explained, was being monopolized by a very few giant corporations. “We have a new body of rulers,” she said, “whose names you don’t know and whose faces you don’t recognize, but who control your life.” These corporate powers, she explained, were a threat to free enterprise. Among other things, they have learned to manipulate the tax laws, not paying their fair share, and leaving the middle class to pay the burden. And one of the threatening economic giants monopolizing the American economy, she said, was the Dow Chemical Company. Well, that charge did not go down well in Midland, Michigan. Two days later, Paul Oreffice, then president of Dow Chemical, immediately fired off an angry letter to Dr. Harold Abel, president of CMU after reading a newspaper story about Fonda’s visit and speech. Oreffice was a no-nonsense corporate manager known for his feisty stands defending his company, and on this occasion, he went right after Fonda and his company’s financial support of CMU:  Paul Oreffice, Dow President. …Yesterday’s paper carried a front page story reporting that Jane Fonda was paid a fee of $3,500 to spread her venom against free enterprise to the student body at your University. Of course, it is your prerogative to have an avowed communist sympathizer like Jane Fonda, or anyone else to speak at your University, and you can pay them whatever you please. I have absolutely no argument with that. While inviting Ms. Fonda to your campus is your prerogative, I consider it our prerogative and obligation to make certain our funds are .never used to support people intent upon destruction of freedom. Therefore, effective immediately, support of any kind from the Dow Chemical Co. to Central Michigan University has been stopped, and will not be resumed until we are convinced our dollars are not expended in supporting those who would destroy us. In addition, resumption of any Dow aid to Central Michigan is contingent on balancing the scales of what your students hear. I am open to an invitation to give a speech to a group of students similar to the one Ms. Fonda addressed for the same fee. This fee will be donated to a non-profit organization which supports the free enterprise system. In subsequent reporting in CMU’s newspaper, Fonda, referring to the Dow letter, expressed her own outrage: “They accused me of being a communist sympathizer. This is a resurrection of McCarthy type red-baiting—if you don’t agree with what someone says you call them a Communist.”… “I am not against business, I am a businesswoman. I am not against profit, I make a profit. I am against corporate irresponsibility and greed..” Fonda was paid $3,500 for her speech, which she donated to Campaign for Economic Democracy. The Fonda-Oreffice flap, meanwhile, went on for the next few months, with news stories and editorials appearing all across the country. Among those who noticed was Washington Post columnist, George Will, who wrote a November 3rd, 1977 column titled, “The Incandescent Fonda”:…although Fonda fancies herself bold beyond belief, in this instance, as in most, her behavior was conventional…. But Dow’s behavior was unconventional. It is, alas, unusual for the business community to balk at subsidizing those who detest it… Capitalism inevitably nourishes a hostile class, but there is an optional dimension of the process. American business has been generous with gifts to universities, but too indiscriminate. Dow has given the business community a timely sample of appropriate discrimination. For a time, there was some reporting in the CMU student paper about the possibility of an Oreffice-Fonda debate at CMU — which Fonda welcomed and at no fee — but that never came to pass. Oreffice and CMU did later smooth things out, and Dow’s support continued. For more on Jane Fonda’s career at this website – her movies, politics, fitness business & videos – see “Fonda Fitness Boom: 1980s & Beyond.” A book by Paul Oreffice, Only In America, is available at Amazon.com. |

EPA, Dioxin, etc.

In addition to the “Fonda flap”, there was also a run-in with EPA when the agency decided in February 1978 to approve some fly-over surveillance of Dow Chemical plants in Midland to check the company’s compliance with the Clean Air Act. But within days of the EPA overflights, Dow sued the EPA charging that the EPA flights violated the company’s Fourth and Fifth Amendment rights – the former prohibiting unreasonable searches, and the latter, prohibiting the taking of property without due process. Dow also charged that its trade secrets could be compromised, as anyone making a Freedom of Information Act request could use the photographs to obtain technical information. In 1982, a U.S. District Court Judge found that EPA had violated Dow’s fourth amendment rights and had exceeded its statutory authority, and prohibited EPA from further aerial surveillance. But EPA appealed the case, and it was reversed by the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals in EPA’s favor by a 2-1 vote. Dow then appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, but EPA’s position was again upheld by a 5-4 vote in 1986.

Map of Michigan & Great Lakes area, showing Dow hometown of Midland and Tittabawassee & Saginaw Rivers, found to have been fouled by Dow wastes and dioxin pollution.

In Midland, Michigan, Dow’s hometown, where the company also had production facilities, there had been long running controversies dating to the 1950s, over the company’s brine well wastes, and later other Dow chemical plant pollution of the Tittabawassee and Saginaw rivers. By 1976-78, dioxin – then being found in Dow wastewater discharges from its plants – had also been found in river sediment and fish.

Then it was revealed in March 1983 that Dow had been given an EPA draft study written by EPA’s Chicago office considering dioxin concerns in the Tittabawassee and Saginaw rivers and the possibility of broader fish consumption bans in the Great Lakes region. The study had been given to Dow by EPA’s assistant administrator in Washington with the Chicago staff instructed to take comments from Dow. According to one EPA participant in a telephone conference call on the report, Dow made clear “what lines and what sections are acceptable to the company and what should be preferably deleted.” In the final report, all mention of Dow as a source of dioxin — and in fact, all reference to Dow — was deleted. The recommendation to prohibit public consumption of fish was also removed, as were the assessments of the human health hazard posed by dioxin in the Great Lakes. The special editing opportunity given Dow in the Great Lakes dioxin study soon became the subject of Congressional hearings in mid-1983, during which the whole episode made front-page news, resulting in the dismissal of the EPA assistant administrator while drawing more attention to Dow and dioxin.

On top of this, also by June 1983, what came to be known as the “Agent Orange papers” were released, revealing that Dow had known about dioxin’s toxicity since 1965. The company had also been engaged in a long running regulatory and legal battle with EPA over the agricultural herbicide 2,4,5-T.

A sampling of newspaper headlines Dow faced on dioxin & other issues in the early 1980s.

The company’s continuing environmental struggles and bad press meant that its corporate name wasn’t winning any popularity contests. So, after a period of some considerable internal Dow soul-searching, a new commitment emerged to put the company on better footing. In the mid-1980s, a Dow task force surveyed employees, managers, directors, government officials, and outsiders about how Dow was then perceived by the outside world. The results were not good: “The current reputation of Dow with its many publics may be at an all-time low,” explained the internal report. “We are viewed as tough, arrogant, secretive, uncooperative and insensitive.”

“We are viewed as tough, arrogant, secretive, uncooperative and insensitive.”

–Dow Survey Report “It was a very difficult time,” later recalled Richard K. Long, Dow’s manager of external communications. “We got accused of things that we felt were inaccurate.” Even some of Dow’s employees at the time viewed the company as arrogant and secretive.” Management began to look at ways in which the company could change perceptions of several key audiences, Long explained.

Keith R. McKennon, president of Dow Chemical USA, would later tell the New York Times: “We had been a proud group who felt that people who knew nothing were telling us what to do. It took us a long time to realize that regulators, legislators, even environmentalists had a right to ask questions.”

”…It took us a long time to realize that regulators, legislators, even environmentalists had a right to ask questions.”

– Keith McKennon So, among other things, in 1985, the company jettisoned its once proud slogan of, “Common Sense – Uncommon Chemistry,” and began a series of upbeat television advertisements built around the theme, “Dow Lets You Do Great Things.” It was Dow’s attempt to both boost internal company morale and woo back the public.

Dow’s intent was to use positive and buoyant themes – which according to Richard F. Dalton, a Dow communications manager – were intended to connect the company to the optimistic attitudes of the 1980s. “Those are the kind of positive feelings we are trying to generate toward Dow,” he explained to Chemical Week in October 1985. “We want the public to see that we’re not a bunch of ogres.”

First TV Ads

Print version of early Dow TV ad of college grad coming to Dow “to help make more and better grain”.

In 1985, Dow spent about $7 million for producing the ads and for air time, but planned a much bigger commitment of $40 million over the next four years for the total campaign, which would also include other outreach and “good cause” undertakings involving social issues or humanitarian causes not connected to the company’s business.

The early press reviews of the Dow make-over were somewhat skeptical, and in a few cases, dismissive and critical. Chicago Tribune columnist, Clarence Page, wrote in December 8, 1985: “If they ever give out prizes for cornball promotions of controversial companies, I have a nomination that should win hands down…” Page wasn’t convinced the ads would do much to woo young people of those times, nor older audiences who still had differences with Dow over Vietnam.

A Fortune magazine story of May 12, 1986 by Faye Rice was headlined, “Dow Chemical: From Napalm to Nice Guy.” In her story she wrote: “The second-largest U.S. chemical company after Du Pont is spending big money and much effort to change its image from combative and arrogant to warm and cuddly.”

Dow, on the other had, was quite pleased with the campaign and what it was finding. Dow’s testing of viewer responses in 1985 showed the ads be effective in “making Dow a highly regarded company among its key publics,” explained Dow’s communications specialist, Richard Dalton.

Back in Midland, however, some long time environmental activists such as Diane Hebert, remained skeptical. “I’m not convinced that there really is a new Dow,” she said.

Politics, Too

But Dow had other audiences in mind, too. “We found that if we were perceived as not running our business in the public interest,” explained Dow chairman Robert W. Lundeen to New York Times reporter Phil Shabecoff in January 1985, “the public will get back at us with restrictive regulations and laws. That is not good for business.” Dow was then selling about $1 billion worth of products directly to consumers. “Our reputation has a real dollar sign on it,” added Lundeen.

Two years later, Dow’s Richard Long, then the company’s public affairs manager in Washington, put more of a political fine point on the same observation. “We had made a lot of enemies who could influence our future. We recognized we had to clean up our act.”

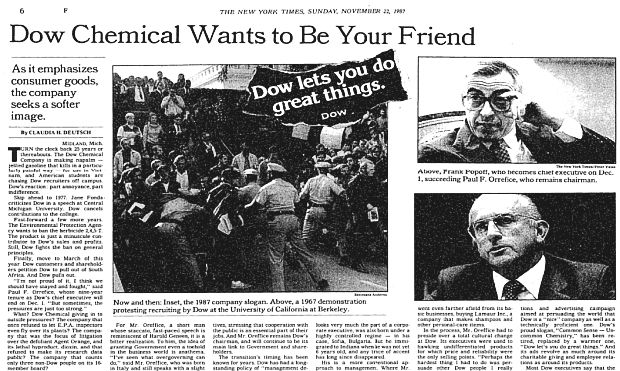

By November 1987, Wall Street Journal reporter, John Bussey, summed up Dow’s PR push and its broader dimensions as follows: “[T]he company is seeking nothing less than public redemption through an extraordinary image-makeover campaign. The ingredients: a schmaltzy $60 million advertising effort; a performance review system that takes into account a manager’s public relations skills; the sharing of more information with regulators; support for legislation that is pleasing even to environmentalists; and, not surprisingly, extra effort to cozy up to the media.” The New York Times also did a focus piece on Dow in November 1987.

November 1987. Portion of a full-page treatment on Dow Chemical in the New York Times showing a photo of a Dow campus protest in 1967, but focusing on the company's new “softer” corporate image, its businesses, and executive changes.

As for the impact of Dow’s TV ads, famous Madison Avenue adman, Bill Backer — who wrote memorable and effective Coca Cola jingles and slogans, such as, “Things Go Better With Coca-Cola”, “It’s The Real Thing,” and “I’d Like to Teach the World to Sing” – told the New York Times in 1989 he thought Dow’s “great things” ad was in the spirit of those upbeat Coke ads that he had done. “After all,” he told the Times, referring to the Dow jingle, “the music almost makes you forget that these are the people who made Agent Orange.” Almost. Vietnam veterans, for one, have not forgotten, as any research online will show.

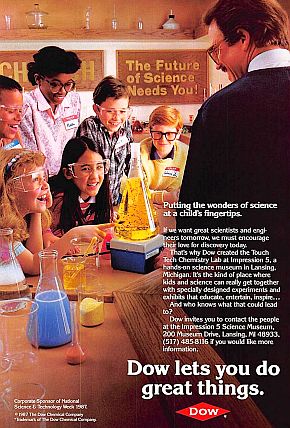

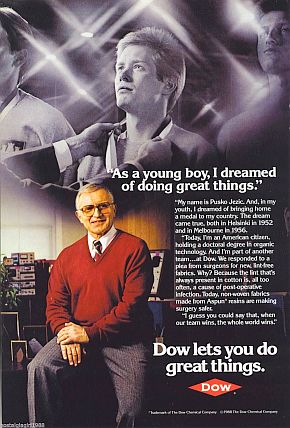

In any case, the Dow “Great Things” campaign was working at its launch in the mid-1980s, and the company kept it and related PR materials running through the late 1980s and beyond – although with new tweaks and varying subject lines, as shown in the examples below.

This 1987 ad sings the praises of a Dow science museum for kids in Lansing, Michigan. |

This 1988 ad profiles a Dow scientist who helped produce a synthetic fabric for safer surgery. |

Dow saw changing times even as its new PR campaign was singing its praises. New issues were emerging. Chemical plant safety came under new scrutiny following Union Carbide’s horrendous toxic gas leak catastrophe at Bhopal, India in 1984. And by 1987, EPA had rolled out the Toxic Release Inventory (TRI), requiring more public pollution reporting by businesses across the U.S. Renewed environmental fervor continued through the 1990s following the Exxon Valdez oil spill of 1989, Earth Day 1990, and updates of environmental laws in Congress. And in more recent years, climate change, plastic pollution, and green energy initiatives have become central concerns.

Changing Image

Dow, of course, has changed with the times, and among other things, became more sophisticated with its advertising and public relations strategies. Take, for example, one of its more recent advertising campaigns, “The Human Element,” fashioned in 2006.

This ad – with Ken Burns-like music, style, and narration cadence – makes its play off the Periodic Table of Elements, running through some of the basic elemental combinations of life, but adding that it is the “human element” that is the most important element; the ingredient that makes all the chemical wizardry possible in the first place. The ads in this series are clearly offering a “softer sell,” more of a celebration of human potential – and of course, implied but not said, Dow’s people applying the human element to make all good things possible. Only Dow’s red diamond logo appears at the end. Still, there’s a little bit of the “all-powerful Dow” suggested in some of this ad’s later renditions — bestowing its gifts and talents on a needy world.

This particular campaign – which had something north of $40 million to spend – also ran print ads in daily newspapers and magazines, including Business Week, The Economist, Newsweek, Scientific American and Time – with some of the magazine spreads beginning at the inside cover and running for six consecutive pages. By 2014 the campaign was tweaked a bit as the “Human Element at Work,” highlighting how Dow’s people and products were improving the human condition. Yes, the world needs Dow.

But beyond the more genteel messaging of Dow’s later ad campaigns, it is important to remember that this company is a very powerful entity capable of wide-ranging impacts – good and not so good – on business, society and the environment.

Dow Chemical Today

Dow Chemical today – in the early 2020s – is a gigantic enterprise, among the top three chemical companies globally, having a presence in 160 countries with some 54,000 employees. Among its manufactures are plastics, chemicals, and agricultural products. As of 2021, annual revenue at the company was running at about $55 billion annually with $6 billion in profit.

In recent years Dow has grown by leaps and bounds, acquiring several other large chemical companies, among them: Union Carbide (1999), Rhom & Hass (2008), and DuPont (2017) – although in the last case, a “de-merger” of Dow and DuPont occurred in 2019 when Dow once again became its own entity. There have also been other combinations, joint ventures and investments that have placed Dow at or near the top of key markets. In January 2017, Dow reached a deal to acquire Corning’s part of the former Dow-Corning joint venture, and is now Dow Silicones Corporation, the largest silicone product producer in the world. Another deal in chlorine with Olin Corp. in 2015 made that venture the global leader in chlorine production (Dow is 50.5% owner). Dow then became one of Olin’s largest U.S. chlorine customers, while retaining its chlorine assets in Europe and Brazil. Dow also agreed to supply Olin with ethylene for 20 years.

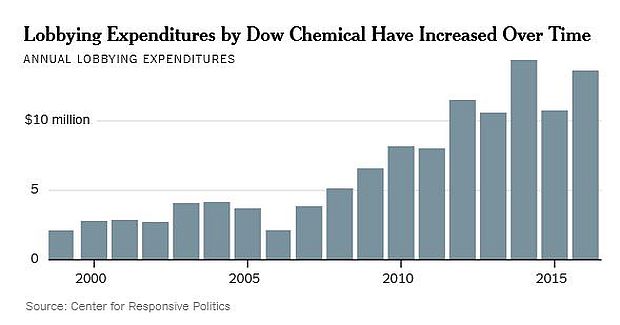

Dow has certainly changed with the times since the 1960s. And true to its mid-1980s TV slogan, Dow, admittedly, has done some great things, not least its continuing contributions to the national economy through its research and innovation. The company has also, on occasion, demonstrated exemplary corporate generosity, social beneficence, and environmental leadership, receiving national and international recognition and awards for its corporate and employee contributions. But make no mistake, Dow Chemical is fully capable of playing political hardball, as its lobbying expenditures of recent years, shown below, illustrate.

Annual lobbying expenditures of the Dow Chemical Company, 1999-2016, as reported in this chart by the New York Times.

And for some, it is the company’s historic performance – it’s corporate résumé, as it might be called – that is still a factor, as well as the kind of chemistry Dow continues to pursue and embed throughout the world. Over its 100 year-plus history, Dow’s primary businesses, its partnerships, and its joint ventures, have had their share of health, safety, and environmental issues.

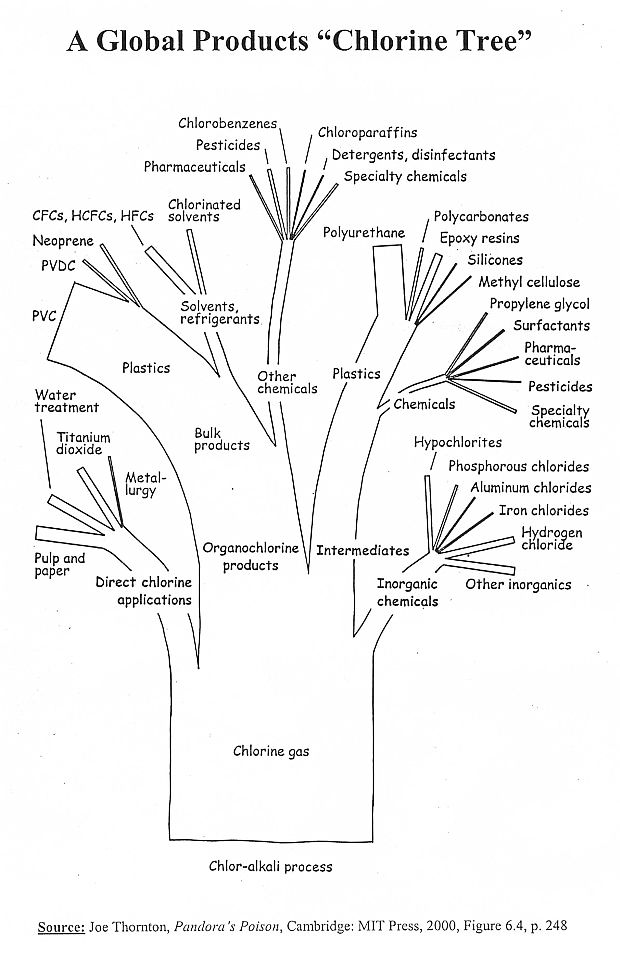

In its primary chemical businesses, Dow has worked in a particularly active region of the Periodic Table of Elements where carbon-based substances containing chlorine, fluorine, bromine, and iodine have been concocted by the thousands. Organochlorine compounds alone, for example, those combining hydrogen, carbon, and chlorine, number in the thousands, and Dow, for most of its 100-plus years, has been a major organochlorine producer and key purveyor of chlorine throughout the global economy. Chlorine, perhaps, might have been explored a bit more in the company’s “Human Element” ad campaign.

Chlorine, in fact, is used in about 60 percent of modern chemical products. About one third of all U.S. chlorine is used to make plastics such as polyvinyl chloride (PVC), found in shoe soles, shower curtains, automobile components and vinyl siding. Chlorine also plays a major role in synthesizing thousands of commercial chemicals such as carbon tetrachloride found in no-stick frying pans, and chlorosilanes used in making semiconductor components or chlorinated solvents.

For most of its history, Dow Chemical has operated within the realm of chlorine, in one way or another.

Yet, the very qualities that have made chlorine an industrial wunderkind in plastics, pesticides, solvents, and more, also make it problematic in the environment, in the workplace, and for public health. Chlorinated chemicals are often persistent in the environment, bioaccummulative, and can be magnified in food chains. Early on, some Dow chemicals made with chlorophenol and sold as Dowicide wood preservatives in the mid 1930s exhibited exposure issues when Mississippi lumberman and Dow production workers in Midland began to have rashes, urinary, and/or other problems (also an early indication, though not always realized, of the embedded dioxin problem).

Dow also had early knowledge of potential health effects from a number of its chemicals—pesticides such as 2,4,5-T, DBCP, and chlorpyrifos (Dursban); plastics such as polyvinyl chloride (PVC) and its precursor/feedstock chemicals, ethylene dichloride and vinyl chloride monomer; plastic ingredient chemical, bisphenol-A; silicone and silicone ingredients; benzene and epichlorohydrin in the workplace; and others. But Dow’s findings on these chemicals weren’t always shared promptly, and in fact, in some cases, were held back.And in the absence of complete and perfect evidence that a chemical was harmful, but suspected as such, or even shown fairly strongly to pose a risk — as in the case of 2,4,5-T — Dow would push out the legal appeals process or stretch out regulatory timetables as far as possible to gain more marketing time. Dow, in these instances, showed itself as a company willing to use its legal powers to the limit, or to make a point, and spared no expense in appeals, public relations, and/or lobbying to wear down or out-last regulators or plaintiffs. All this, of course, within their legal rights.

In some of the company’s businesses and partnerships, Dow historically has also had problems – from radioactive waste at a Dow-managed nuclear bomb trigger plant at Rocky Flats, Colorado (1951-1975) and suspected birth-defects linked to a morning sickness drug, Bendictin, sold by its Dow-Merrell pharmaceutical unit in the early 1980s, to health effects of DowCorning silicone breast implants in women (1980s-1990s), or various worker health and safety issues over the years related to on-the-job toxic chemical exposures.

Cathy Trost’s 1984 book, “Elements of Risk,” an excellent history of Dow up to that time (Times Books, 337pp). Click for copy.

…Dow — whose legacy includes making napalm during the Vietnam War and much of the plastic waste polluting the world’s oceans today—is also, somewhat improbably, woke. The company has scored a perfect 100 on Human Rights Campaign Foundation’s Corporate Equality Index every year since 2005, meaning it meets every requirement for an LGBT-friendly workforce. These include having policies protecting employees from discrimination, benefits for domestic partners, coverage of the health needs of transgender employees, and a track record of advocating publicly for LGBT causes…

Laudable as such changes may be, the proof of other important improvements at Dow will need to come in its on-the-ground performance at production facilities and how it deals with its legacy costs. Chief among the latter are its dioxin-related clean-up challenges. On November 15, 2007, for example, EPA and Dow Chemical signed a consent order to begin an emergency cleanup of a previously unknown dioxin hot spot on the Saginaw River. Under earlier June 2007 EPA orders, Dow had been removing three dioxin hot spots from the Tittabawassee River. The new hot spot location was a half-mile below the confluence of the Tittabawassee and Shiawassee Rivers. “The extremely high level of dioxin found in the Saginaw River,” said regional EPA administrator, Mary A. Gade at the time of the consent order, warranted the immediate action. Dow discovered and reported the latest hot spot during sampling done under its September 2007 work plan. As EPA explained in its announcement, “Dow’s Midland facility is a 1,900-acre chemical manufacturing location. Dioxins and furans come from the production of chlorine-based products. Past waste disposal practices, fugitive emissions and incineration at Dow resulted in dioxin and furan contamination both on- and off-site.” So the dioxin cleanups in Michigan will continue for some time. Dow also has acquired legacy and environmental clean-up costs with its Rohm & Hass and Union Carbide subsidiaries.

In addition, over the last decade or so, there have been ongoing issues of spills, fires, flaring, worker and community risks, Superfund clean-ups, and other issues at Dow locations. From the year 2010 through the early 2020s, for example, Dow facilities in the U.S. have had numerous incidents, with fines, penalties and settlements in the tens of millions of dollars. Among some of these are the following:

Cover of “The Dow Sustainability Report,” 2009 Global Reporting Initiative. Dow has pledged to improve its performance.

TRI Reporting. For the year 2010, Dow Chemical ranked as the nation’s second-largest toxic waste producer in pollution reporting required under the U.S. Toxic Releases Inventory (TRI), with more than 600 million tons reported.

Midland Pollution Charges. In late July 2011, EPA and the U.S. Department of Justice announced that Dow agreed to pay a $2.5 million civil penalty to settle alleged violations of the Clean Air Act, Clean Water Act and the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) at its chemical manufacturing and research complex in Midland, Michigan. A 24-count complaint had been filed for alleged environmental violations related to its chemical, pharmaceutical and pesticide manufacturing.

Bristol Plant Blaze. On May 21, 2012, a three-alarm fire at Dow Chemical’s Bristol, PA plant caused two tanks to release chemicals to the air. The chemicals released were ethyl acrylate and butyl acrylate, according to Bucks County officials. Dow officials reported at the time that the material was contained, but as the cleanup moved forward chemical odors might still be a factor in the region. Area residents were advised that the chemicals could cause minor throat or eye irritation, headaches and nausea, but that such symptoms would lessen as the air cleared.

Dow acquired Rohm & Haas in 2008.

Lab Worker Killed. On October 11, 2013, a 51-year-old lab worker at Dow Chemical’s Rohm & Haas Electronic Materials plant in North Andover, MA was killed by an explosion when a volatile chemical – trimethylindium, classified as “pyrophoric,” meaning it can spontaneously catch fire – was accidentally exposed to air in the lab. Local authorities believed it was either a malfunction of the container or human error that caused the accident. At the time, local authorities and OSHA were investigating, and the U.S. Chemical Safety Board had also requested information on the incident. Less than three years later, on January 7, 2016, another explosion at this same plant occurred, seriously injuring four workers. In that case, OSHA fined Rohm & Haas $129,000 for serious infractions, but after the company contested the penalties, two of the serious violations were dropped and the fine reduced to $71,000. The company vowed to stop using pyrophoric chemicals in all U.S. operations. The Boston Business Journal at the time reported that Dow planned to close the North Andover plant in 2016, and move the work to South Korea.

Dow managed the Rocky Flats nuclear facility from 1951 to 1975.

Kentucky Air Pollution. On August 17, 2016, Dow Corning received notification from the Kentucky Department for Environmental Protection (KDEP) of their intent to assess a civil penalty in excess of $100,000 for alleged air violations at Dow Corning’s Carrollton, Kentucky, manufacturing facility (discussions between Dow Corning and the KDEP were ongoing, and final resolution is unclear).

Dow Silicones Pollution. In June 2019, Dow agreed to a consent decree, pay a penalty of $4.55 million, implement a series of measures to reduce pollutant emissions, and spend $1.6 million to support environmental projects in the community. In March 2012 and April 2015 EPA identified alleged emissions and pollution violations at Dow Silicones Corp.’s chemical manufacturing facility in Midland, MI. Dow was charged with violating the Clean Air Act, the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act, the Clean Water Act, the Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act and the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act. According to the Justice Department, Dow failed to monitor and repair leaks of volatile organic compounds (VOCs), such as toluene, and also failed to properly operate the facility’s thermal oxidizer for controlling hazardous air pollutants (HAPs), such as benzene, resulting in excess emissions. Dow also allegedly failed to identify hazardous waste streams and properly manage and monitor stormwater, which may have allowed the discharge of hydrochloric acid, benzene, and heavy metals, including arsenic, known to be harmful to aquatic species, into the Lingle Drain and Tittabawassee River. Dow agreed to take actions to achieve annual emission reductions of 218 tons of HAPs and 43.53 tons of VOCs, as well as three tons of nitrogen and zinc.

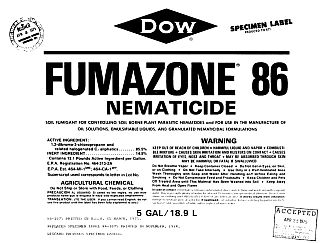

1975 product label for Dow brand, ”Fumazone,” a DBCP pesticide that was banned in the U.S. in 1977.

Tank Explosion. On November 3, 2019, a tank at a glycol processing unit at Dow’s Plaquemine, LA plant exploded with a loud boom, shaking homes and rattling windows nearby. The tank contained water and small levels of sulphuric acid, ethylene oxide and nitrogen, which are used for a variety of manufacturing purposes. Following the blast, Dow said the incident was caused by a ruptured vessel and no injuries were reported. OSHA opened an investigation a day after an explosion, and on April 24, 2020, cited Dow for several serious safety violations. In May 2020, OSHA announced a fine of $53,976 for the explosion, but Dow was then appealing the citations.

Map used by WDSU-TV (New Orleans, LA) for November 3, 2019 news story, “Explosion Confirmed at Dow Manufacturing Plant Near Plaquemine” (Iberville Parish).

Toxic Air & Water Rank. Based on 2019 data, the Political Economy Research Institute at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, ranked Dow Chemical at No. 2 on its list of “Toxic 100 Water Polluters Index” and No. 6 on its list of “Toxic 100 Air Polluters Index.”

Natural Resource Damages. Under a November 2019 settlement announced by the United States, the State of Michigan and the Saginaw Chippewa Indian Tribe of Michigan, Dow Chemical will implement and fund an estimated $77 million in natural resource restoration projects intended to compensate the public for injuries to natural resources caused by the release of hazardous substances from Dow’s Midland, Michigan facility. According to a complaint filed on behalf of federal, state and tribal natural resource trustees, Dow’s release of dioxin-related compounds and other hazardous substances damaged natural resources. The complaint, filed under a Superfund natural resources damage claim, alleges that hazardous substances from Dow’s facility adversely affected fish, invertebrates, birds and mammals, contributed to the adoption of health advisories to limit consumption of certain wild game and fish, and resulted in soil contact advisories in certain areas including some public parks. The settlement requires Dow to implement and fund natural resources restoration projects that will benefit fish and wildlife and provide increased outdoor recreation opportunities for the American public.

Texas Superfund Site. In December 2020, it was announced by EPA that Dow and other companies will pay nearly $2 million to clean up the Gulfco Marine Maintenance Superfund Site in Freeport, Texas, according to the agency’s complaint and proposed consent decree, filed in U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Texas.

Photo shows earlier flaring at Dow’s Plaquemine, LA plant, July 8, 2012 (Louisiana Environmental Action Network ).

An aerial view of the Dow Chemical complex at Plaquemine, Louisiana, located along the Mississippi River some 15 miles south of Baton Rouge.

Chlorpyrifos Lawsuits. On July 12, 2021, lawsuits were filed in four California counties seeking potential class-action damages from Dow Chemical and its successor company over a widely used insecticide containing the chemical, chlorpyrifos. Chlorpyrifos was patented by Dow in 1966, and for more than 50 years it has been used widely in agriculture on millions of acres in the U.S. and around the world. It has also been used extensively on golf courses, buildings (termite control), and other applications. Over the last decade or more, there has ben a running regulatory and legal battle over banning and restricting the chemical over its alleged health effects, especially in children. As of August 18, 2021, EPA announced a ban on the use of chlorpyrifos on food crops. In California, meanwhile, litigation has begun seeking health-effects damages. According to October 2020 reporting by Bloomberg Law.com, “dozens of chlorpyrifos lawsuits” can be expected in California. All of the suits vary to some degree, but many center on a finding that chlorpyrifos degrades into an analog that is 1,000 times more toxic than its parent – a residue that has a durable tenacity, and can cling to walls, furniture, car dashboards, toys and more. A variety of childhood developmental health issues have been associated with chlorpyrifos including: autism, obesity, vision problems, and brain damage, some beginning with exposures in pregnancy.

Evacuation Order. On July 21, 2021, the Office of Emergency Management at La Porte, Texas issued an evacuation order for anyone living within a half-mile radius of the Dow Chemical plant on Bay Area Blvd in La Porte. At issue was a chemical tanker truck at the facility leaking a chemical, hydroxyethyl acrylate. The truck’s tank body was docked in a parking area with others at Dow Chemical’s La Porte plant, shown in the news photo below being sprayed with water.

News photo from July 21, 2021, showing tank truck area at Dow Chemical’s LaPorte, TX chemical works and tanker units being sprayed with water, as one was leaking at the time, with fears of possible fire and/or explosion.

The evacuation order was issued in the event the materials inside the tank caused a fire or explosion, possibly spreading to other areas of the complex. Two other truck tanks holding chemicals were then near the problem tanker. One held the same product, hydroxyethyl acrylate, and another contained methyl methacrylate. Some rail cars in the area are also shown the photo. Two other production facilities also within a half-mile of the Dow plant were also of some concern. Fortunately, there was no major incident, and the evacuation and a shelter-in-place orders were later lifted.

California Sues. In October 2021, The California attorney general filed a civil lawsuit against Dow and other companies at Dow’s Pittsburg, CA production site to stop the dumping and release of toxic materials into the environment and nearby communities. The Dow plant, located 40 miles northeast of San Francisco along the New York Slough, manufactures fertilizers, insecticides, and other products in an area with 70,000 residents. The Pittsburg plant, operating since 1939 on a 1,000 acre site, is less than a mile from the Corteva Wetlands and not far from the San Joaquin and Sacramento rivers, whose waters eventually reach San Francisco Bay. In the complaint the California Department of Toxic Substances Control (DTSC), names Dow Chemical, Dow Agrosciences, Corteva Agrisciences, and others. Among the charges are more than 1,000 instances of illegal treatment of wastewater with hazardous levels of toxic and corrosive chemicals during 2016, 2017, and 2020 without DTSC authorization. The charges also include operating numerous tanks that were either open or had open vents which could lead to uncontrolled emissions of toxic chemicals. The court has the authority to impose civil penalties of up to $25,000 per day per violation for violations which occurred prior to January 1, 2018, and up to $70,000 per day per violation for violations occurring on or after January 1, 2018.

The Dow Chemical Pittsburgh, CA plant site is located along the New York Slough, not far from the San Joaquin and Sacramento rivers, whose waters eventually reach San Francisco Bay. Map source, San Francisco Chronicle.

The Pittsburg plant has also had previous and ongoing problems, including groundwater contamination with earlier litigation in June 2002 involving an underground plume of chemical contaminants that included chlorinated solvents and suspected carcinogens such as perchloroethylene, carbon tetrachloride, methylene chloride, and trichloroethylene. In 2015, Contra Costa County health officials issued public alerts to residents in Pittsburg and Antioch after thousands of pounds of chemicals were released from the plant. And in 2018, four Dow employees at the Pittsburg location were hospitalized after being exposed to chlorine gas that had leaked inside the facility.

Chlorine Release. On April 18, 2022, a fire began in a compressor unit that converts gas to liquid at an Olin Chemicals operation located inside the Dow Chemical facility at Plaquemine, Louisiana, 15 miles south of Baton Rouge. Chlorine was then released from what appeared to be a rupture of chlorine equipment. A huge cloud resulted and moved slowly over the facility. Iberville Parish Sheriff Brett Stassi said the leak started around 8:40 p.m. which prompted local authorities to issue a shelter-in-place order for nearby residents to stay indoors, not use air conditioning, and close all windows and doors. The leak occurred less than one-quarter of a mile from subdivisions in the north Plaquemine area. A Baton Rouge TV station reported that 23 residents were taken to Ochsner Medical Center near Plaquemine. None of the residents were hospitalized, according to Iberville Parish Emergency Management Director, Clint Moore.“They weren’t necessarily hospitalized, and to my knowledge, none were actually admitted,” he said. “They were brought there as precautionary measure.” Iberville Parish President, J. Mitchell Ourso, who issued a shelter-in-place order, said the smell of chlorine was reported in the air several miles from the facility. A photo from the scene showed a large plume of smoke billowing from the site.

April 18, 2022. Photo of smoke cloud from Olin fire & chlorine release at Dow’s Plaquemine, LA chemical complex on the west bank of the Mississippi River near Baton Rouge, LA Photo: Rodney Waldroup

During the incident, officials shut down route LA-1 in both directions near the scene. The shelter-in-place ended about 12:30 a.m. It lasted approximately 3 ½ hours. Iberville Parish President Ourso, who issued a shelter-in-place order, later noted: “It could’ve been so much worse… Nobody got hurt in the complex and nobody was overcome here in the public.” A statement issued from Olin at the time of the incident noted that “monitoring confirms there is no risk of offsite exposure” and that “no injuries have been reported…” However, in early May 2022, an Iberville Parish resident who was hospitalized with severe chemical exposure reactions from the chlorine gas leak filed an injury lawsuit against the owners and operators of the Olin chlor-alkali plant at the Dow Chemical facility.

A New Dow?

Dow Chemical, it seems, is still dealing with a considerable roster of legacy issues, as well as ongoing environmental, worker safety, and public health concerns. Hopefully, there are better days ahead for the Dow Chemical Company. Or, as its advertising of old so optimistically offered, only “great things” ahead – benign, safe, and non-toxic things – in all of its ventures.

Other stories at this website with related or similar content include, “Power in the Pen,” the story of Rachel Carson’s 1962 best-selling book, Silent Spring, which rocked the chemical industry and helped spur the modern day environmental movement. See also, “…A Richer Harvest,” a story profiling Union Carbide pesticide advertising in the 1960s, which also tells a larger story about toxic chemicals and the horrific 1984 Bhopal, India toxic gas catastrophe, as well as related leaks in West Virginia. And finally, the “Environmental History” topics page includes additional stories on air pollution, oil spills, river pollution, industrial accidents, strip mining, and other issues.

Thanks for visiting — and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research and writing at this website and its continued publication. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

____________________________________

Date Posted: 21 August 2022

Last Update: 21 August 2022

Comments to: jackdoyle47@gmail.com

Twitter: https://twitter.com/PopHistoryDig

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Doing Great Things? – Dow Chemical,

1960s-1980s” PopHistoryDig.com, August 21, 2022.

____________________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

Don Whitehead, The Dow Story: The History of the Dow Chemical Company, New York: McGraw-Hill, 1968.

Cathy Trost, Elements of Risk: The Chemical Industry And Its Threat To America, New York: Times Books, 1984,

E.N. Brandt, Growth Company: Dow Chemical’s First Century, East Lansing, Michigan Sate University Press, 1997.

Jack Doyle, Trespass Against Us: Dow Chemical & The Toxic Century, Common Courage Press, 2004.

“Dow Chemical,” Wikipedia.org.

1986 Dow Labs, “Graduation” TV Commer-cial,” YouTube.com, posted, August 20, 2018.

“Dow Chemical Protest,” The Daily Breeze (Torrance, CA), May 29, 1966.

“Napalm Protests, 1966 / Napalm Protests At Factories and Naval Base” (California), Harvey Richards Media Archive, EstuaryPress.com.

William Pepper, “The Children of Vietnam,” Ramparts, January 1967, pp. 45-68.

H. D. Doan, President, The Dow Chemical Company, “Dow Will Direct Its Efforts Toward a Better Tomorrow,” The Dow Diamond (company magazine), No. 4, 1967, 4pp.

Colleen Leahy, “Remembering The Dow Protest And Riot 50 Years Later; Author: UW-Madison ‘Dow Day’ Protest Ushered In The ’60s,” Wisconsin Public Radio / WPR.org, Air Date, October 18, 2017.

June Dieckmann, “76 Hurt in UW Rioting; Campus Strike Results. Police Hemmed; No One Jailed,” Wisconsin State Journal (Madison, WI), October 19, 1967, p. 1.

Roger Gribble, “UW To Charge Riot Leaders; Dow Co. Interviews Suspended,” Wisconsin State Journal, October 19, 1967, p. 1.

James Oset, “Students, Faculty Vote Strike Today; Protesting Police Action,” Wisconsin State Journal, October 19, 1967, p. 1.

Gerd Wilcke, “Dow Will Ignore Campus Protests; Napalm Maker Reports Its Recruiting Unaffected,” New York Times, October 27, 1967, p. 6.

“35 Arrested at IU [Indiana University] Sit-in,” Indianapolis Star, October 31, 1967.

“Student Demonstrations – Dow Chemical,” Indiana University Archives Exhibits, Indiana.edu, accessed June 22, 2022.

“1967 Dow Chemical Sit-in, Part 1,” Indiana University Archives / Libraries.Indiana.edu.

“Students: Ire Against Fire,” Time, November 3, 1967.

Susana Oredson, “Reader Gives Facts on Dow Demonstration,” Daily Herald-Telephone, November 6, 1967.

“Dow Chief Says Protests Hurt,” New York Times, November 18, 1967.

“Dow Protest Becomes Riot; Police Use Gas, Clubs on Crowd,” Spartan Daily (San Jose State College, San Jose, CA), November 21, 1967, p. 1.

Charles Pancratz and Bob Kenney, “Student Opinion Divided On Anti-Dow Sentiment,” Spartan Daily, November 22, 1967, p. 3.

Jeff Brent, “Dow Representative Says SJS Protests ’Worst Yet’,” Spartan Daily, November 22, 1967, p. 4

“Governor Reagan Demands Discipline for Protesters,” Spartan Daily, November 22, 1967, p. 6.

Roy Petty, “Fasters, Campers Begin Long Vigil to Protest Dow,” Daily Iowan, November 29, 1967.

Terrence R. Bertele, “Dow Calls Off NYU Recruiting As 250 Picket Here and Uptown,” Washington Square Journal (New York University, NY, NY), November 30, 1967, p. 1.

“Dow Defends Napalm,” Washington Square Journal, November 30, 1967, p. 1.

“Patriotism May Require Opposing the Government at Certain Times” – Howard Zinn’s Antiwar Speech at Indiana University, December 1, 1967. Indiana Magazine of History, Indiana University, June 2014 (Introduced, Transcribed, & Edited by Alex Lichtenstein).

“Anti-Dow Rally Erupts at UI [University of Iowa],” Iowa City Press-Citizen, December 5, 1967. p. 1.

“Protestors Lead Cops on Wild Race to the Tune of ‘Dow Must Go Now’,” Daily Iowan, December 6, 1967, p. 1.

Tony Shultz, “Torrance Plant Under Fire: Supporters, Foes of Napalm Present Their Arguments,” Los Angeles Times, December 10, 1967, p. CS-1.

“Napalm Protests Worry Dow, Though Company Is Unhurt,” New York Times, December 11, 1967.

Ken Reich, “Police Break Up Fights: Marchers, Hecklers Scuffle in Torrance Antiwar Parade,” Los Angeles Times, December 18, 1967, p.1.

“Dow Chemical Attempts Recruiting at N.Y.U., and a Protest Results,” New York Times, March 7, 1968, p. 58.

“Dow Chemical, University of Michigan Exhibit: Resistance and Revolution: The Anti-Vietnam War Movement at The University of Michigan, 1965-1972,” Umich.edu.

“Dow Stock is Sold by Union Seminary,” New York Times, January 11, 1969, p. 31.

“The Dow Chemical Demonstrations – Feb-ruary 5, 1969,” Duke.edu (Duke University).

“Napalm: Student Power Crushes Dow,” RyanBodanyi.org / Students for Bhopal.

Jerry M. Flint, “Dow Recruiters Try a New Tactic; Hope to Counter Protests on Campus Over Napalm,” New York Times, February 10, 1969, p. 53.

“9 Protestors Held in Dow Break In,” Washington Post, March 23, 1969.

Patrick McGrath, “Dow Office Attacked, Files Scattered,” National Catholic Reporter, April 2, 1969.

Frank Carroll, “‘Dow Shalt Not Kill’: The Story of the D.C. Nine,” BoundaryStones.WETA .org, January 23, 2020.

Saul Braun, “Going the Rounds With a Dow Recruiter,” New York Times Sunday Magazine, April 13, 1969, p. 27.

Associated Press, “Church Unit Sells Shares Of Dow Chemical Stock,” New York Times, June 11, 1969, p. 58.

“Napalm and The Dow Chemical Company,” PBS.org/WGBH (“Two Days in October” article).

Associated Press, “Dow Declares It Has Stopped Production of Napalm for U.S.,” New York Times, November 15, 1969, p. 34.

Jerry Flint, “Napalm Bid Lost, Dow Still Target; It Expects Further Protests Despite Contract End,” New York Times, November 23, 1969.

“Corporations: Dow Drops Napalm,” Time, November 28, 1969.

Kathy Jennings, “Fonda Raps Business ‘Tyrants’,” Central Michigan Life (Central Michigan University), October 12, 1977, p. 1.

Kathy Jennings, “Fonda Ponders Action Against Dow,” Central Michigan Life, November 2, 1977, p. 1.

Sharon Johnson, “Fonda Offers Return Speech; Would Sponsor Own Rebuttal,” Central Michigan Life, November 2, 1977, p. 1.

“Oreffice Debate Okay With Fonda,” Central Michigan Life, November 4, 1977.

“Dow-Fonda Face-Off Unlikely, But Possible ” Central Michigan Life, November 9, 1977.

Associated Press, “Dow Chemical Says U.S. Spied on Plants by Air,” New York Times, March 22, 1978, p, D-2.

Deborah Baldwin, “The War Comes Home” (re: 2,4,5-T domestic use), Environmental Action, April 1980, pp. 3-8, 31-32.

April Moore, “And Here’s The Filthy Five” (Dow Chemical among them), Environmental Action, April 1980, pp. 9-11.

William A. Buckingham, Operation Ranch Hand: The USAF and Herbicides in Southeast Asia, 1961-1971, Office of Air Force History, U.S. Air Force, 1982, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C.. 265pp.

Leslie Maitland, “E.P.A. Aides Charge Superiors Forced Shift in Dow Study,” New York Times, March 19, 1983.

David Burnham, “Dow Says U.S. Knew Dioxin Peril of Agent Orange,” New York Times, May 5, 1983, p. A-18.

Stuart Taylor Jr., “Study Links Dioxin to Immune Failure,” New York Times, June 3, 1983, p. 1.

Janice R. Long and David J. Hanson, “Dioxin Issue Focuses on Three Major Controversies in U.S.; Furor Developing Around the Question of Dioxin Exposure Has Reached a Head in Three Cases – Agent Orange, Times Beach, and Tittabawassee River,” Chemical & Engineering News, June 6, 1983.

U.S. House of Representatives, Washington, D.C., Hearing Report No. 78, “Dioxin – The Impact on Human Health,” Committee on Science & Technology, Subcommittee on Natural Resources, Agricultural Research & the Environment, 98th Congress, 1st Session, June 30, July 13, 28, 1983.

Joan Beck, “Agent Orange Case: Who Won?” Chicago Tribune, May 9, 1984, p. 14.

Ralph Blumenthal, “Veterans Accept $180 Million Pact on Agent Orange,” New York Times, May 8, 1984, p. 1.

“Litigation Continued for Years” (re: Agent Orange timeline), New York Times, May 8, 1984, p. 36.

John J. O’Connor, “NBC Film on Agent Orange Dispute,” New York Times, November 10, 1986, p. C-22.

Marcia Barinaga, “Agent Orange: Congress Impatient for Answers,” Science, 245, 1989, pp. 249-250.

Michael Millenson, “Vets’ Scientific Task Force Links Agent Orange 5 Types of Cancer.” Chicago Tribune, May 2, 1990, p. 13.

Jan Banout, Ondrej Urban, Vojtech Musil, Jirina Szakova, and Jiri Balik. “Agent Orange Footprint Still Visible in Rural Areas of Central Vietnam,” Journal of Environmental and Public Health, 2014.

Laura Smith, “The Agent Orange Trial Proved That U.S. Chemical Companies Killed Our Soldiers, But Got Away With It. ‘I Died in Vietnam and Didn’t Even Know it’,” Timeline.com, July 20, 2017.

“Agent Orange” (Dow Statement & Position), Corporate.Dow.com.

“Dow Lets You Do Great Things,” YouTube .com, posted, September, 1, 2017 (internal corporate communication via Eva-Tone Sound-sheet highlighting Dow’s 1985 promotional/ awareness marketing campaign, with commentary and full song).

Philip Shabecoff, “Dow Stoops to Calm Congress and Public Opinion,” New York Times, January 2, 1985.

James Schwartz and Mimi Bluestone, “Dow Dons Velvet Gloves in Its New Round of Ads,” Chemical Week, October 30, 1985, pp. 36–39.

Clarence Page, “Dow Ads: Rebuilding a Seared Image,” Chicago Tribune, December 8, 1985.

Stuart Diamond, “Problems at Chemical Plants Raise Broad Safety Concerns,” New York Times, November 25, 1985, p. 1.

Faye Rice, “Dow Chemical: From Napalm to Nice Guy; The Company That Once Slugged it Out With Environmentalists, Lawmakers, and Reporters Is Trying to Change its Image,” Fortune, May 12, 1986.

Robert Knight, “Dow Chemical Cultivates a New Image,” Washington Post, September 21, 1986, p. D-7.

John Bussey, “Softer Approach: Dow Chemical Tries to Shed Tough Image and Court the Public,” Wall Street Journal, November 20, 1987, p. A-1.

Claudia H. Deutsch “Dow Chemical Wants to be Your Friend,” New York Times, November 22, 1987.

“1988 – Dow Lets You Do Great Things – Germany TV Ad,” YouTube.com.

“The Media Business; Fewer Ad Jingles Are Heard As Madison Ave. Shifts Beat,” New York Times, June 19, 1989, p. D-1.

Dow Chemical Co., 1988 brochure, “Dow At A Glance: Celebrating Ninety-Two Years of Quality Performance,” Midland, Michigan.

Barry Meier, “Dow Chemical Deceived Women On Breast Implants, Jury Decides,” New York Times, August 19, 1997, p. 1.

“1991 Ad For Dow’s ‘Angel Flights’,” (using empty seats on corporate jets for cancer patients), Dow Commercial 1991, YouTube .com, posted, February 21, 2016.

Joe Thornton, Pandora’s Poison, Cam-bridge: MIT Press, 2000

“Dow Chemical Confirms Hydrogen Cyanide Release Near Houston,” Oil & Gas Journal / OGI.com, March 8, 2001.

Rob Vanya, “Hampshire Accepts OSHA Settlement Agreement,” Chron.com, August 2, 2001.

Jane Kay, “Dow Settles Suit over Tainted Water with Cash, Cleanup / Pittsburg Plant to Treat Aquifer, Pay $3 Million,” San Francisco Chronicle / Sfgate.com, April 4, 2002.

Rick Bragg, “Toxic Water Numbers Days of a Trailer Park,” New York Times, May 5, 2003.

Justin Wilfon, “Chemical Spill At Dow Corning Plant Disrupts Highway, Water And Rail Traffic,” Wave3.com (Louisville, KY), July 22, 2004.

Juliet Eilperin, “Dow Chemical Is Told to Curtail Pesticide Sales,” Washington Post, December 29, 2004.

“Two Days In October,” American Experi-ence, PBS.org, 2005.

Stuart Elliott, “How Now, Dow?,” New York Times, June 26, 2006.

“The Dow Chemical Company Agrees to Enter Consent Order and Pay Civil Penalty for Hazardous Waste Violations,” DEP data.CT.gov/enforcement, July 16, 2007.

Felicity Barringer, “Michigan: Dioxin Deal,” New York Times, July 18, 2007.

Reuters Staff, “EPA Notifies Dow Chemical of Likely Violations,” Reuters.com, Novem-ber 9, 2007.

“Dow to Clean up Dioxin Hot Spot in the Saginaw River,” EPA.gov, November 15, 2007.

“EPA Reaches Agreement with Dow Corning on Clean-Air Violations,” EPA.gov, February 29, 2008.

DOW “The Human Element,” Vimeo.com.

Cedric Dawkins Ph.D., “Dow Chemical and Agent Orange in Vietnam,” The CASE Journal, May 1, 2008.

L. Layton, “US Cites Fears on Chemical in Plastics,” Washington Post, April 16, 2008, p. A-1.

“Dow Chemical Accused of Violations in Ledyard,” HartfordBusiness.com, October 3, 2008.

Sarah A. Vogel, PhD, “The Politics of Plastics: The Making and Unmaking of Bisphenol A ‘Safety’,” American Journal of Public Health, November 2009.

PR Newswire, “31st Complaint Filed in Rohm & Haas/Dow Chemical Illinois Cancer Cluster Litigation,” Layser & Freiwald, P.C., April 29, 2010.

“Texas Fines Dow Chemical Subsidiary $542,251 for Multiple Air Quality Violations,” BloombergLaw.com, August 26, 2010.

Anna Lappe, “What Dow Chemical Doesn’t Want You to Know About Your Water,” Grist.org, June 9, 2011.

Saliqa Khan,“ Cleanup Ongoing At Dow Chemical Plant In Bristol,” Patch.com, May 21, 2012.

Neil H. Dempsey, “State IDs Peabody Man Killed in Dow Explosion,” SalemNews.com (Danvers, MA), October 12, 2013.

John Aguilar, “$375M Settlement Reached in Homeowner Lawsuit Against Rocky Flats,” DenverPost.com, May 19, 2016.

Associated Press, “Dow Chemical Is Pushing Trump Administration to Ignore Studies of Toxic Pesticide,” Los Angeles Times, April 20, 2017.

Opinion, “Trump’s Legacy: Damaged Brains; This Is What a Common Pesticide Does to a Child’s Brain,” New York Times, October 28, 2017.

Kevin Roose, “Why Napalm Is a Cautionary Tale for Tech Giants Pursuing Military Contracts,” New York Times, March 4, 2019.

“Dow Chemical Company Settlement,” EPA.gov/Enforcement, July 29, 2011.

Rebecca Williams, “Dow Chemical Co. Ranked Second-Largest Toxic Waste Producer in the Nation,” MichiganRadio .org, January 12, 2012.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, “Chlorine and Chlorinated Hydrocarbon Data: Collection and Analysis Summary,” Office of Water (4303T), February 2012, Washington, DC.

Dianna Wray, “Chemically Burned: Dow Chemical Tries to Avoid Hot Water in Worker’s Death,” HoustonPress.com, June 13, 2013.

Ted Goldberg, “Agency Investigating Chemical Release at Pittsburg Dow Chemical Plant,” KQED.org, March 27, 2015.

“Three Held for Observation after Chlorine Leak Near Baton Rouge,” CBSnews.com, December 2, 2016.

Mark Schleifstein, “Dow Chemical in Plaque-mine Evacuated for Olin Corp. Chlorine Leak,” NOLA.com / The Times-Picayune, December 3, 2016.

Zoe Mathews, “Mechanical Failure Caused Dow Chemical Explosion; OSHA Issues Multiple Serious Violations After Investi-gation Into Incident,” EagleTribune.com (North Andover, MA), March 29, 2017.

Hiroko Tabuchi and Tryggvi Adalbjornsson, “From Dow’s ‘Dioxin Lawyer’ to Trump’s Choice to Run Superfund,” New York Times, July 28, 2018.

Jeff Green. “How Dow Chemical Got Woke. The Big Conservative Chemical Company with a Legacy of Making Napalm During the Vietnam War Has a Gay CEO,” Bloom-berg.com / Businessweek, March 20, 2019.

“Groups Take Legal Action Against Dow Chemical for Violating Hazardous Waste Laws,” Environmental Integrity Project / EnvironmentalIntegrity.org, May 15, 2019.

Annie Sciacca, “Dow’s Pittsburg Plant Breaking Environmental Laws, Groups Say; Chemical Company Sent Notice of Lawsuit; Ignoring Hazardous Waste Regulations Alleged,” EastBayTimes.com, May 15, 2019.