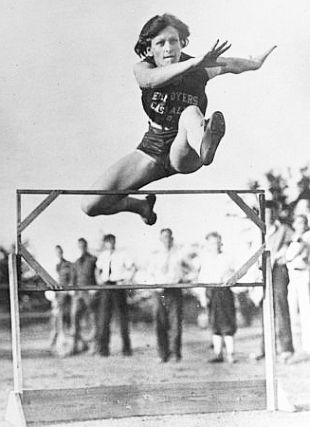

1932 AP photo of Babe Didrikson vaulting high hurdle used as the model for the Sport Kings card above.

For this skill her sandlot associates nick-named her “Babe” after Babe Ruth, the immortal New York Yankee slugger who was then redefining baseball with his own home-run hitting. Young Mildred was also called “Bebe” at home by her mother.

But Babe Didrikson was much more than a good sandlot baseball player. In fact, when it came to athletics, there was little she couldn’t do. More on her career in a moment.

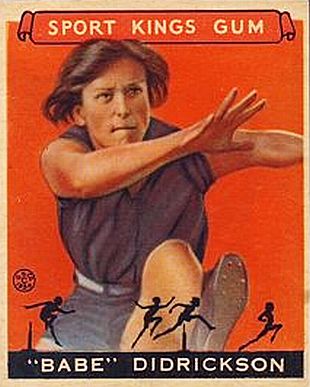

Mildred “Babe” Didrikson is shown at right on a 1933 Sports Kings chewing gum trading card, one of the few artistic renderings of her in action, in this case, jumping over a high hurdle.

The rendering is taken from a 1932 Associated Press photo shown later below.

Unfortunately, her name is incorrectly spelled on the trading card, using a “c” in her family name where none is needed.

Still, the Sports Kings card is quite rare and desirable among collectors. The Sport Kings series of trading cards was released by the Goudey Gum Co. of Boston, Massachusetts in 1933 and 1934. This particular series featured 48 athletes from a cross-section of sport, among them: swimmer Johnny Weissmuller, football star Red Grange, boxer Max Baer, hockey icon Howie Morenz, and baseball immortal Babe Ruth. Highly prized by modern sports card collectors, the original Sport Kings cards today are among the most popular sets of sports trading cards.

Babe Didrikson

Babe Didrikson was born in June 1914, at Port Authur, Texas. She was the sixth of seven children born to Ole and Hanna Marie Didrikson. Ole Didrikson was a ship’s carpenter who had sailed the world’s oceans many times before settling down. He encouraged his young daughter to partake in sports. As a child, among other things, she spent time jumping hedges, a skill later displayed in her track and field endeavors.

1932 AP photo of Babe Didrikson vaulting high hurdle used as the model for the Sport Kings card above.

“I can still remember how her muscles flowed when she walked.” Lytle explained. “She had a neuromuscular coordination that is very, very rare—not one of the 12,000 girls I coached after that possessed it….” Babe led her high school basketball team, and also began to play golf around that time. But she first came to national attention when she played for a Dallas-based, industrial league basketball team that won the national Amateur Athletic Union championship. In 1929, she was named an All-American basketball player. But then came track and field.

Between 1930 and 1932, at 16-to-18 years old, Didrikson compiled records in five different track and field events. In one remarkable display of her athletic abilities, she won a 1932 national amateur track meet for women, a team event, all by herself. On July 16, 1932, at the AAU track and field championships in Evanston, Illinois., Babe was the lone representative of Employers Casualty Insurance Company of Dallas, where she worked as a typist. At the Illinois meet, which was also the tryout for the Olympic games, she was competing against company teams of 12, 15, and 20 or more women.

Babe Didrikson, second from right, in the hurdles race at the 1932 Olympics. AP photo. |

Babe Didrikson won gold in the javelin event at the 1932 Olympics with a record-setting throw of 143' 4". |

Babe Didrikson, 2nd from left at tape in hurdles race, ahead of Evelyne Hall, for gold medal, 1932 Olympics. |

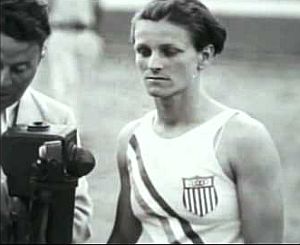

Babe Didrikson with photographer at the 1932 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles. |

According to one account, when Didrikson was introduced in Evanston, she ran onto the field by herself waving her arms wildly as the crowd gasped at the audacity of this “one-woman track team.” Still, Babe won five of the eight events she entered – shot put, baseball throw, long jump, javelin, and 80-meter hurdles. She tied for first in a sixth event, the high jump. In qualifying for three Olympic events, she amassed a total of 30 team points for Employers Casualty. In a single afternoon Didrikson had set four world records, taking first place overall in the meet and scoring more points than the next best finisher – an entire women’s athletic club – the Illinois Women’s Athletic Club, scored 22 points, with 22 athletes.

At the 1932 Olympic games in Los Angeles – which ran from July 30 to August 14th at the L.A. Coliseum – she qualified for five Olympic events, but women were then only allowed to compete in three. She won gold in the javelin, the first ever for a female in that event, making a throw of 143 feet 4 inches and setting a world record. She also took gold in in the 80-meter hurdles with a time of 11.7 seconds.

In the high jump, she won the silver medal behind Jean Smiley, though they each broke the world record. Babe, in fact, cleared the high-jump bar at a world-record height, and would have won that event too, except for her technique – clearing the bar headfirst– ruled ineligible (later known as the “Fosbury flop” and legal).

Newspapers of the day recognized Babe’s prodigious Olympic feats. One headline read: “Babe Gets Praise on Coast; Is Called the Greatest Woman Athlete of the World.” Sportswriter Grantland Rice, after her Olympic Games performance, was quite the admirer: “She is an incredible human being. She is beyond all belief until you see her perform…” Rice believed she was in a category all her own, with few rivals. Associated Press would name her Woman Athlete of the Year in 1932 – a distinction she would win five more times. In the press she was also called “Wonder Girl” and “super athlete.”

Yet in 1932, the participation of women in the Olympics was a hotly debated topic. In fact, many then believed that competitive athletics was strictly for men only. Still, in the summer and fall of 1932, following the Olympics, Babe Didrikson became famous throughout the land.

On August 11, 1932, at her return home from the Olympics, she arrived on the mail plane. Coming into Dallas, a crowd of thousands awaited to greet her. At her reception in the city she was introduced by a local official as “the Jim Thorpe of modern women athletes.” The crowd cheered. One of her hometown newspapers in Beaumont, Texas, The Enterprise, marked the occasion with these headlines: “World-Famous Babe Is Given Tumultuous Dallas Welcome Amid Ticker Tape Showers—She Tells of Having Picture Taken With Clark Gable.”

At one point, Babe met Amelia Earhart, who was then doing some of her less known long-distance flights and wanted Babe to join her believing that Didrikson’s name might bring notice to those attempts. Didrikson remained earth-bond, however, and after the Olympics hysteria wore off, Babe faced a harder reality. She found there was little money in her athletic fame, especially for those in amateur athletics – and doubly so for women. And the country at the time was also mired in the Great Depression.

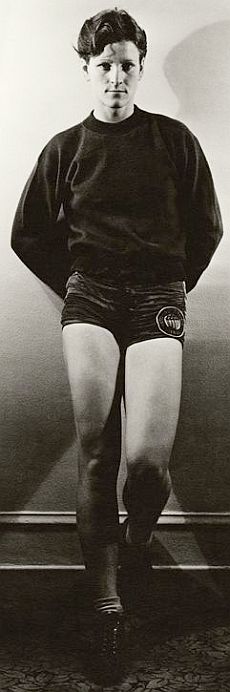

Babe Didrikson, 19, in photo by Lusha Nelson that appeared in the January 1933 issue of ‘Vanity Fair’ magazine.

Not long thereafter, she helped the Chrysler Corporation promote its Dodge cars. Welcomed in Detroit by Mayor Murphy, Babe appeared at the Detroit Auto show and worked at the Chrysler display booth chatting with visitors and signing autographs. Chrysler also lined up an advertising man to organize bookings for her. He arranged some stage appearance for Babe on the RKO vaudeville circuit, one of which was at the Palace Theater in Chicago, where “Babe Didrikson” had top billing on the marquee and was given the top star’s dressing room.

On stage, Babe traded opening jokes with a companion comedian, did a track-star type skit, and played a few tunes on a harmonica. Audiences loved her act, and fans lined up for blocks to see her, not only in Chicago, but later in Brooklyn and Manhattan in New York.

Although making good money on stage – as much as $2,500 a week in New York, then a small fortune – Babe wanted to be outdoors. After a week or so on the Vaudeville circuit, she cancelled her remaining bookings and decided to look for some way to use her athletic skills.

She then turned to performing at various competitive exhibitions – from billiards to a few appearances with a professional women’s basketball team. She would also master tennis, and became an accomplished diver, a good swimmer, and a graceful ballroom dancer. She also excelled at sewing, and reportedly made some of her own clothes. But in the press, after her athletic fame emerged, she began to be criticized for her manly ways. A 1932 Vanity Fair article, had called her a “muscle moll,” while other accounts cut even deeper.

By March 1933, however, she decided to take up golf, a sport she had dabbled in a few times and had played some in high school. But now she thought about golf more seriously, and went to California to take lessons from a young golf pro named Stan Kertes. She worked on developing her golf game for six months until she ran out of savings, then went back to her old $300-a month job at Employer’s Casualty in Dallas.

Young Babe Didrikson, 1930s.

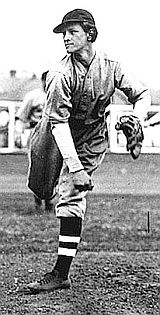

By spring of 1934, it was on to baseball in Florida during spring training – where Babe would pitch an exhibition inning or two working with professional teams such as the Brooklyn Dodgers, Boston Red Sox, Philadelphia Athletics, and other teams. In these contests, Babe was paid a certain amount of money per inning, as the teams were using her as a publicity stunt. But in these outings, Babe also met the famous players of that day, including Jimmie Fox, Dizzy Dean, and Babe Ruth — with whom she struck up a long standing friendship.

Babe Didrikson pitching for minor league New Orleans team in 1934. AP photo.

In 1934, Babe also made the next move in her athletic career: she entered the Texas Invitational Women’s Golf Tournament at Forth Worth. Babe didn’t win that tournament. But the following year, in the spring of 1935, she entered the Women’s Texas Amateur at the River Oaks Country Club in Houston, one of the state’s finer clubs. And it was here that she began to confront country club elitism. As Sports Illustrated writers William Oscar Johnson and Nancy Williamson would observe in 1975:

…Babe had to crack…Texas golf society. She had no pedigree, coming as she did from a dead-end neighborhood in Beaumont, no money and not much social grace. Her gold medals from the 1932 Olympics counted for little among the country-club set, and her fame had already faded. There was only her golf game, at that point strong but scarcely smooth. When she entered the Texas event, a member of the Texas Women’s Golf Association named Peggy Chandler declared, “We really don’t need any truck drivers’ daughters in our tournament.”

Babe Didrikson, in good golfing form, 1930s.

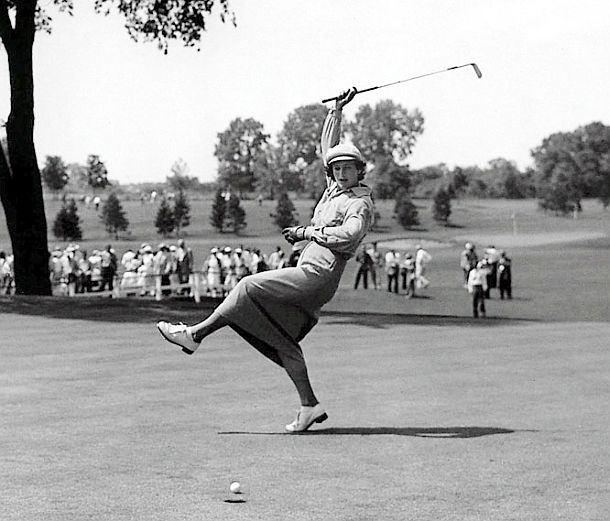

By 1937 she was getting the attention of male golfers for the drives she was making during an exhibition tour of the Southeast. And at the Pinehurst Golf Course in New York where she was practicing for an exhibition match in November 1937, one reporter noted that she “astounded the critical Pinehurst Galleries by hitting the ball 260 yards off the tee on the championship courses.”

In January 1938, she decided to make a try for men’s competitive golf, aiming for the Los Angeles Open, a men’s Professional Golfers’ Association (PGA) tournament. This was a feat no other woman would attempt until Annika Sörenstam, Suzy Whaley, and Michelle Wie took up the challenge some 60 years later. In the 1938 L.A. tournament, Babe was teamed up with George Zaharias, a former professional wrestler who she would later marry. In the PGA tournament, meanwhile, she shot 81 and 84, and missed the cut.

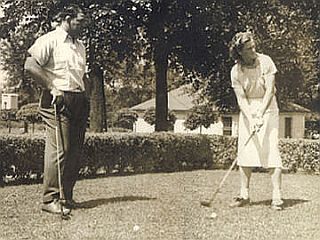

George Zaharias & Babe Didrikson, Normandie Golf Club, St. Louis, late 1930s.

Babe won the Women’s Western Open in 1940, and after gaining back her amateur status in 1942, she won the 1946 U.S. Women’s Amateur and the 1947 British Ladies Amateur – the first American to do so. She also won the Women’s Western Open in 1944 and 1945.

In July 1944, Time magazine wrote that Babe had “popped back into the sports pages by winning a major golf tournament,” trouncing a 20-year-old college girl in the finals of the Women’s Western Open at Chicago. “As usual,” wrote Time, “Babe’s booming drives were seldom in the fairway, but her recoveries were so phenomenal that she had 14 one-putt greens in 31 holes.” By then, her husband, George Zaharias, who often accompanied her to her golf matches, was running a custom tailoring establishment in Beverly Hills, California next door to Babe’s women’s sport clothing store.

Babe Didrikson with trophy at the Miami Biltmore Country Club, Feb. 1, 1947 for winning the Helen Lee Doherty Women's Invitational Tournament. AP photo.

By 1947, she had once hit a golf ball over 400 yards and was averaging 240 yards on her drives. Asked how in the world a woman could possibly drive a golf ball 250 yards down the fairway, Babe explained, “You’ve got to loosen your girdle and let it rip.”

In addition to her power off the tee, she was also known for having soft touch around the greens. She was also a favorite among fans in the gallery, gaining cheers for her play and laughter for her jokes and banter.

In 1948 and 1950s, she won the Women’s Open. In 1950, along with Patty Berg, she founded the Ladies Professional Golf Association (LPGA). Few professional tournaments then existed for women, so Babe and several other women golfers set about establishing the LPGA to introduce more paying tournaments. Gradually, with sponsorship monies from sporting goods companies, the women’s tour increased its purses and credibility, with a growing number of women able to eke out a living in golf.

Ben Hogan and Babe Didrikson Zaharias congratulate each other after their respective victories in the World Championship Golf Tourney at Tam O' Shanter Country Club, near Chicago, IL, August 12, 1951. AP photo.

Later, in 1950, she was named AP’s Woman Athlete of the First Half of the Twentieth Century. In 1951, she won the Tampa Open and was also the leading money-winner that year.

In 1952 she took another major with a Titleholders victory, but illness prevented her from playing a full schedule in 1952-53.

Then in 1953, still at the top of her game, she was diagnosed with cancer, and for a time it was thought she might give up the game. She had surgery in April 1953.

Babe Didrikson in action during U.S. Women's Open Championship of 1954, which she would win. Photo: AP/Sports Illustrated.

Babe was on a mission by this time to give encouragement to others who were battling cancer. She used her celebrity to get the message out. She appeared as a guest on ABC’s TV show, The Comeback Story, explaining her attempts to battle colon cancer. But Babe had not been told the full extent of her own cancer, as she had believed she would beat the disease. Still, she became a spokesperson for fighting the disease, helping the American Cancer Society. In late 1955, however, her cancer reappeared and she was hospitalized again. With her, in the corner of the room, were her golf clubs, as they had been during her previous hospital stays.

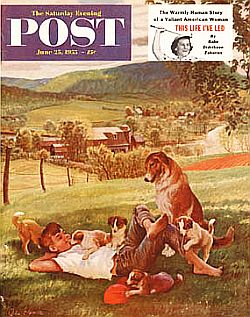

Saturday Evening Post of June 25, 1955, with cover inset (upper r.) announcing excerpt of Babe Didrikson’s book, “This Life I’ve Led.”

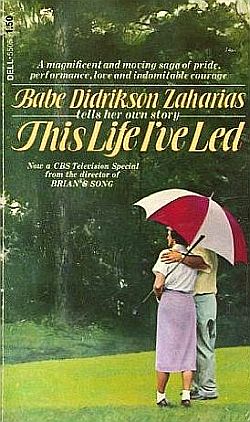

By June 1955, her autobiography, titled This Life I’ve Led, as told to Harry Paxton, was published by A.S. Barnes & Co.,. That summer, the Saturday Evening Post began running parts of the book in installments. “The warmly human story of a valiant American woman,” said the Post in a top corner cover inset for its June 25, 1955 issue, featuring the book’s title along with a small photo of Babe with a golf club raised above her head.

Didrikson continued to crusade against cancer, and spoke openly about her illness in an era when most public figures preferred to keep their medical troubles private. She battled her cancer to the end, but succumbed to the disease in September 1956. She was 45 years old.

Eisenhower’s Praise. On the morning she died in a Galveston, Texas hospital, President Dwight D. Eisenhower began his news conference in Washington with this salute: “She was a woman who, in her athletic career, certainly won the admiration of every person in the United States, all sports people all over the world, and in her gallant fight against cancer, she put up one of the kind of fights that inspire us all.”

President Eisenhower getting golf tips from Babe Didrikson at the White House, April 1, 1954, as the president uses the American Cancer Society’s "Sword of Hope" for a substitute golf club. Babe had presented the Sword to the president after he opened the 1954 Cancer Crusade, then lighting a huge "Sword of Hope" in New York's Times Square by remote control. AP photo.

The sportswriter Grantland Rice once said of her, “The Babe is without any question the athletic phenomenon of all time, man or woman.”

Charles McGrath, the editor of the New York Times Book Review, wrote in 1996: “She broke the mold of what a lady golfer was supposed to be. The ideal in the 20s and 30s was Joyce Wethered, a willowy Englishwoman with a picture-book swing that produced elegant shots but not especially long ones. [Didrikson] developed a grooved athletic swing reminiscent of Lee Trevino’s, and she was so strong off the tee that a fellow Texan, the great golfer Byron Nelson, once said that he knew of only eight men who could outdrive her.”

Mildred Babe Didrikson Zaharias, in any case, had an impressive athletic career, stretching from her All-American basketball designation in the early 1930s and her record-setting Olympic achievements of 1932, to a prolific amateur and professional golf career that ran into the mid-1950s.

Totaling both her amateur and professional competitive golf victories, Babe won some 82 tournaments. Associated Press named her “Female Athlete of the Year” in 1932, 1945, 1946, 1947, 1950, and 1954.

|

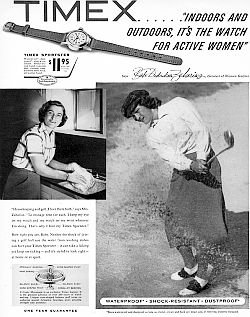

“Babe, The Money Machine” As Babe Didrikson rose to fame – both following her 1932 Olympics’ performance and during her golf career through the mid-1950s – she became something of a hot property for business and product endorsements. For some of the promotions, exhibitions, and advertising in which she engaged, Babe appears to have been a willing participant. But in other respects, those around her and those profiting from her – including her husband, George Zaharias; her business manager, Fred Corcoran; and the emerging professional women’s golf circuit – all commanded her attention, and in her later years, drove her into quite a frenetic pace of activity.  Babe Didrikson offering an endorsement for Wheaties at the bottom of a 1935 magazine ad.  This 1950s Timex watch ad touted Babe’s golf stardom and her domestic/homemaker side. During the latter stages of her golf career it was estimated she was earning more than $100,000 a year for exhibitions, endorsements, and other activities connected with sports. Sometimes, Babe would hype the amount of money she was getting paid for various events or contracts, as she did once for a movie deal for a series of instructional golf films, saying she would be paid $300,000, which was untrue, but widely reported nonetheless, helping to inflate her value. She also authored instructional golf articles occasionally and at least one book, Championship Gold. And in 1952, she also had a bit part in the Spencer Tracy / Katharine Hepburn film, Pat and Mike.  1930s: Goldsmith & Sons sales literature touting "Babe Didrikson Coordinated Golf Equipment."  More promotional material from Goldsmith & Sons, displaying Babe's news clips, while touting “the powerful, sales-producing publicity surrounding Babe Didrikson...”  Babe Didrikson posing with two of her golf trophies in the 1950s. |

In 1975, a TV biography about her life and times titled Babe, starred Susan Clark as Babe and Alex Karras as George Zaharias. A number of books have also been written about her life and athletic career, a few of which are mentioned or pictured below in “Sources.”

Babe Didrikson Zaharias, late 1940s.

Babe was also, according to various profiles, more of a self-promoter than was generally known, prone to boasting and exaggerating her feats – although some say this could be confused with her sense of humor taken the wrong way. Still, she could be an “in your face” competitor, sometimes compared in her boasting to a later practitioner of that art, Muhammad Ali. Sports Illustrated writers William O. Johnson and Nancy Williamson noted her braggadocio at the 1932 Olympics using that comparison:

…She was producing her own myth in Los Angeles. The remarkable thing about Babe was that, like Ali, her body was able to accomplish the fantastic tasks her big mouth set for it. She put incredible pressure on herself by bragging. She was a wing walker, a daredevil who risked humiliation every time she went into an event in that Olympics. Her own teammates wanted her to be beaten, as the just reward for her bullying…

On the golf circuit too, especially in her younger years, she is reported to have shown up at the clubhouse exclaiming to competitors: “The Babe’s here! Who is going to finish second?” But more often than not, Babe found a way to win. Yet her considerable talents were augmented by lots of practice, to which she would readily admit. The formula for success is simple, she would say: “practice and concentration, then more practice and concentration.” Dutiful practice was the key, as she advised – “in any case, practice more than you play.” In her early days, she was known to hit golf balls for hours on end, until her hands bled or had to be taped.

Aug. 4, 1950: Babe Didrikson Zaharias, displaying her playful side, urging the golf ball toward the cup on the 18th green during the All American Women’s Open at Chicago’s Tam O’Shanter Club. Photo, Ed Maloney /AP.

But Babe Didrikson above all, was a determined soul; a person who persevered through tough times as a female athlete. Following her phenomenal Olympic rise, she rode something of a “fame-to-bust” roller coaster, also confronted by judgmental societal attitudes and personal digs from the press. She managed, however, to keep herself afloat economically during a Great Depression using her athletic skills in a variety of exhibitions until she found her golf calling. And once there, after dealing with some country club elitism and prejudice, she proceeded to change and enliven the game for the better, while in later years, opening doors for and encouraging younger female golfers who followed. And all the while, among her most steadfast supporters, was her hometown of Beaumont, Texas, where today the Babe Didrikson Zaharais Museum is found alongside the Babe Didrikson Zaharais Park.

For other stories at this website on notable women and their careers see, for example: “Power in The Pen,” about Rachel Carson and her book, Silent Spring; “Dinah Shore & Chevrolet,” about the famous 1950s singer and TV star who also promoted Chevrolet automobiles, and, “The Flying Flapper,” about the fearless aviatrix, Elinor Smith, who set many flying records in the 1920s-1930s. See also the topics page, “Noteworthy Ladies,” which offers additional story choices on women who have made their mark in various fields. More sports stories can be found at the Annals of Sport category page. Thanks for visiting – and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research and writing at this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

____________________________________

Date Posted: 17 April 2013

Last Update: 15 March 2018

Comments to: jdoyle@pophistorydig.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “1930s Super Girl, Babe Didrikson,”

PopHistoryDig.com, April 17, 2013.

____________________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

1932, Chicago: Babe Didrikson dressing up. |

Babe Didrikson was also a very capable swimmer & diver, turning in competitive times and scores in various meets during the 1930s. Lamar University archives. |

Babe Zaharias Park is adjacent to the Babe Didrikson Museum in Beaumont, TX. |

“Clips Record in Hurdles; Miss Didrikson Lowers National Mark in Meet at Dallas,” New York Times, Sunday, June 28, 1931, Sports, p. S-2.

Associated Press, “Five First Places to Miss Didrikson; Dallas Girl Scores 30 Points to Win A.A.U. Championship for Her Team at Evanston,” New York Times, Sunday, July 17, 1932, Sports, p. S-1.

“Babe Didrikson Is Honor Guest at Luncheon,” Beaumont Enterprise, August 17, 1932.

“Sport: Golfer Didrikson,” Time, Monday, May 6, 1935.

“Babe at 30,” Time, Monday, July 3, 1944.

“Mrs. Zaharias Ousts Miss Casey In Denver Golf Tourney,” New York Times, Friday, July 12, 1946, Sports, p. 23.

“Whatta Woman,” Time, Monday, March 10, 1947.

Gene Farmer, “What A Babe!, Texas Tomboy is First U.S. Woman To Win British Golf Championship,” Life, Jun 23, 1947, pp. 87-90.

“Mrs. Zaharias Advances; Defeats Mrs. Reidel in Texas Open – Gets 6 under Par 69,” New York Times, Wednesday, October 13, 1948, Sports, p. 34.

Associated Press, “Mrs. Zaharias’ Course-Record 70 Leads Field at Tam O’Shanter; Star 2 Strokes Under Men’s Par in First Round…,” New York Times, Friday, August 4, 1950, Sports, p. 16.

Babe Zaharias, “This Life I’ve Led,” part 2, Saturday Evening Post, July 2, 1955; part 3, Saturday Evening Post, July 9, 1955; part 4, Saturday Evening Post, July 16, 1955; and, part 5, Saturday Evening Post, July 23, 1955.

Babe Didrikson Zaharias, This Life I’ve Led, New York: A.S. Barnes & Co., 1955.

Babe Didrikson Zaharias, This Life I’ve Led – My Autobiography, Internet Archive.

Jimmy Jemail, “The Question: Is Babe Didrikson The Greatest All-Round Athlete Of All Time?,” Sports Illustrated, June 6, 1955.

Joan Flynn Dreyspool, “Subject: Babe and George Zaharias,” Sports Illustrated, May 14, 1956.

Obituary, “Babe Zaharias Dies; Athlete Had Cancer,” New York Times, September 28, 1956.

Paul Gallico, “Farewell To The Babe,” Sports Illustrated, October 8, 1956.

George Zaharias, “The Babe and I,” Look, 1957.

Theresa M. Wells, “Greatness for Mildred Didriksen Indicated In 1923 Clippings,” Sun-Enterprise (Beaumont, TX), April 27, 1969, p. 18.

William Oscar Johnson and Nancy Williamson, “Babe,” Sports Illustrated, October 6, 1975.

William Oscar Johnson and Nancy Williamson, “Babe Part 2,” Sports Illustrated, October 13, 1975.

William Oscar Johnson and Nancy Williamson, “Babe,” Sports Illustrated, October 20, 1975

William O. Johnson and Nancy P. Williamson, Whatta-Gal!: The Babe Didrikson Story, Little Brown & Co., 1977.

“Mildred Didrikson Zaharias,” Encyclopedia of World Biography.

Susan E. Cayleff, “The ‘Texas Tomboy’ – The Life and Legend of Babe Didrikson Zaharias,” OAH Magazine of History, Organization of American Historians, Summer 1992.

Charles McGrath, “Babe Zaharias: Most Valuable Player,” New York Times Magazine, 1996.

Susan E. Cayleff, Babe: The Life and Legend of Babe Didrikson, Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1996, 368pp.

Thad Johnson with Louis Didrikson, The Incredible Babe: Her Ultimate Story, Lake Charles, Louisiana: Andrus Printing and Copy Center, Inc., 1996.

Russell Freedman, Babe Didrikson Zaharias: The Making of a Champion, New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1999, 192pp.

Paula Hunt, “Babe Didrikson Zaharias – Top 100 Women Athletes,” Sports Illustrated, 2000.

Randall Mell, “Legacy Of Babe: 50 Years Ago She Won Third And Final Open, Sun Sentinel (Fort Lauderdale, FL), June 29, 2004.

Sonja Garza, “The Life of Babe Didrikson Zaharias,” BeaumontEnterprise.com (with photo gallery), Friday, June 17, 2011.

Don Van Natta, Jr., “Babe Didrikson Zaharias’s Legacy Fades,” New York Times, June 25, 2011.

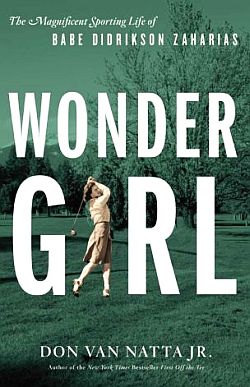

“Wonder Girl,” Don Van Natta Jr.,” YouTube .com.

“Babe Didrikson Zaharias,” Special Collections and Lamar University Archives, Lamar University, Beaumont, Texas.

The Promiscuous Reader, “A Good Ol’ Gal From Beaumont, Texas,” This is So Gay/Blogspot, Sunday, February 6, 2011.

Rhonda Glenn, “Babe Didrikson Zaharias – Whatta’ Gal,” U.S. Women’s Open.com.

Rick Burton, “Searching for Sports’ First Female Pitchman,” New York Times, January 1, 2011.

___________________________________