The familiar logo of ESPN, the sports cable TV network.

The familiar logo of ESPN, the sports cable TV network.

After being turned down by a half a dozen or more potential investors, Rasmussen met Stu Evey an executive vice president at Getty Oil who managed a variety of projects for the oil company. Evey used Getty’s financial experts to analyze the market and evaluate what might result from investing in the new venture. In February 1979, Getty initially agreed to put up $43,000 for an option to buy 85 percent of the new cable sports network. Millions more in Getty dollars would follow.Sports Illustrated called ESPN “one of the strangest creations in the history of mass communications.” Stu Evey would become ESPN’s first chairman and would later write a book about the experience (see below). On September 7, 1979, a Saturday evening at 7 p.m., the “Entertainment Sports Programming Network” launched its first program as a regional sports cable channel. It began with a show called “Sports Center.” A few weeks later RCA awarded Rasmussen the satellite space for 24-hour programming. ESPN was on its way, for good or ill. The first few years entailed a hodge-podge of programming — slow-pitch softball, kick boxing, racquetball, volleyball, karate, Australian Rules football, Irish hurling, tractor pulls, and other arcane sports. Broadcasting through the weekends and a few hours each weekday, the station lost millions of dollars. Sports Illustrated called it “one of the strangest creations in the history of mass communications.” Still, ESPN had the industry’s attention.

NCAA Basketball

Former Getty Oil v.p. Stu Evey's 2004 book on the making of ESPN. Click for copy.

Former Getty Oil v.p. Stu Evey's 2004 book on the making of ESPN. Click for copy.

In August 1982, ABC television agreed to supply some programming to ESPN in exchange for an option to purchase up to 49 percent of the company. ESPN meanwhile, began more coverage of college football in 1982, and a year later began its first professional sports broadcasting with the games of the fledgling United States Football League (USFL). The USFL coverage lasted three years and also included some programming outside of the U.S. ESPN also made a major business change in 1983 by beginning to charge cable companies — rather than paying them — for carrying its programming. Even though this only resulted in pennies per subscriber per year, it nonetheless marked a turning point toward profitability. Still, ESPN was operating in the red but it was now reaching more than 23 million households.

ABC & Cap Cities

In 1984, ABC shelled out more than $225 million to acquire ESPN.

In 1984, ABC shelled out more than $225 million to acquire ESPN.

In 1990, The Wall Street Journal ranked ESPN # 1 on cable, ahead of CNN & MTV, with 54.8 million subscribers. By the early 1990s, the cable TV revolution was in full flower with CNN, MTV, and other major networks. And in the new industry, ESPN was found among the top players. A Wall Street Journal ranking of the major cable operators in 1990 placed ESPN at #1 with 54.8 million subscribers, ahead of #2 CNN with 53.8 million, and #6 MTV with 49.3 million. ESPN was still growing. In March 1992 ESPN’s international division acquired 50 percent of the European Sports Network. At home, ESPN Sports Radio was also launched in 1992 and a second TV channel, ESPN-2, debuted in October 1993 beginning a focus on sports such as soccer, in-line skating, and mountain biking. In early May 1994, ESPN acquired Creative Sports a TV/radio sports marketing, syndication, and production company which was later renamed ESPN Regional Television. In January 1995, ESPN distributed the Super Bowl game to television outlets in more than 100 countries. Then came Disney.

Disney Takes Over

In August 1995, the Walt Disney Company, one of the world’s largest entertainment corporations, announced it would acquire Cap Cities/ABC for $19 billion. The deal stunned Wall Street and the entertainment industry. But one of the assets Disney was most pleased about getting in the deal was ESPN. At the time, Disnsey’s chairman Michael Eisner called ESPN “a magic name,” comparable to Coca-Cola or Kodak in brand recognition. The all-sports network by then was seen in 66.3 million American households and 95 million around the world. ESPN had already become a booming profit center for ABC. “The channel has been our biggest growth area on a percentage basis over the past five years,” said Robert A. Iger, ABC’s president in August 1995. Disney’s Michael Eisner called ESPN “a magic name,” comparable to Coca-Cola or Kodak in brand recognition. Media analysts were then projecting good days ahead. ESPN and ESPN-2 were slated to generate cash flow of $350 million in 1995 and $400 million in 1996, making it the most profitable of all cable TV services. ESPN was then worth between $4 billion and $5 billion. Everywhere that Disney CEO Michael Eisner went in New York that August touting the deal — from newspaper and radio interviews to Larry King Live — he couldn’t say enough about ESPN. He also saw the possibility of “brand build-out” just as Disney had done with its own products. “We know that when we lay Mickey Mouse or Goofy on top of products, we get pretty creative stuff,” Eisner said. “ESPN has the potential to be that kind of brand. ABC has never had our resources, and we haven’t had ESPN. Put the two together and who knows what we get.” ESPN’s sports fare was also unique in its live coverage aspects, marketable most anywhere in the world.

ABC and Disney executives had already concluded that the most exportable forms of TV entertainment were sports and children’s programming because they have universal appeal and offend no political position. “But the leverage of those two together in what used to be third world countries, or closed countries, is enormous,” explained Eisner in August 1995. The most “exportable” forms of TV entertain- ment, it was thought, were sports and children’s programming because they had universal appeal and offended no political position. “There are 250 million people in the middle-class of India alone…” Disney also liked ESPN’s aggressive marketing of its sports news and information around the world, from Latin America and Europe to Asia and Australia, seeing additional potential for cable and satellite-delivered, locally popular sports like cricket in India or table tennis in China. “We think sports is a good inter-national language,” said Steven Bornstein, ESPN’s president. Disney technology could then transmit a single channel into every corner of the globe, and was looking for more new and distinct programming to telecast and incorporate into its stores and theme parks.

1997: ESPN Classic begins.

1997: ESPN Classic begins. 'ESPN Zone' restaurant & enter-tainment center at 1472 Broadway in New York.

'ESPN Zone' restaurant & enter-tainment center at 1472 Broadway in New York.

In 1998, ESPN The Magazine was launched, and has since become a serious competitor to Time, Inc.’s Sports Illustrated with nearly 2 million subscribers. In 2001, the Bass Anglers Sportsman Society was acquired and became the basis for more than two dozen ESPN Bass tournament and fishing shows. In 2002, ESPN and ABC acquired television broadcasting rights for National Basketball Association (NBA) games. But football continued to be a mother lode for ESPN. In 2005, when ESPN paid $1.1 billion for the rights to Monday Night Football, some business analysts thought the network paid a too rich a price. But by the end of 2006 it was clear that ESPN had captured a worthy share of households and cable viewers — averaging in the 10-to 12-million range — and producing the largest household audiences of the year for at least 16 consecutive weeks. But still more contracts were on the way.

European soccer, 2006.

European soccer, 2006.

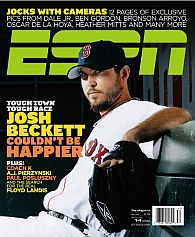

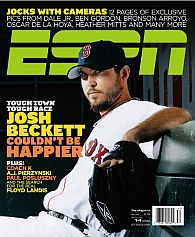

ESPN, The Magazine, August 2006.

ESPN, The Magazine, August 2006.

* * * * * * * *

A summary of some of ESPN’s more prominent parts (as of April 2008) and its ever-growing empire follows below:

Travis Vogan's 2015 book, "ESPN: The Making of a Sports Media Empire," University of Illinois, 256pp. Click for copy.

Travis Vogan's 2015 book, "ESPN: The Making of a Sports Media Empire," University of Illinois, 256pp. Click for copy.ESPN

The flagship network, ESPN, is now seen in 94 million households with programming that inlcudes coverage of more than 65 sports including MLB, NBA, NFL’s Monday Night Football, NASCAR, FIFA World Cup, WNBA, college football, men’s and women’s college basketball, golf, Little League World Series, and the X Games. ESPN Original Entertainment creates branded program-ming outside of ESPN’s normal fare, and ESPN on Demand offers sports and other exclusive content from ESPN and outside sources.

ESPN-2

ESPN-2 is now seen in over 93 million households. Its programming features NASCAR racing, MLB, college football and basketball, golf, tennis, FIFA World Cup, MLS, and more. It also offers “Cold Pizza,” a two-hour morning show that combines sports with pop culture and “lifestyle features.”

ESPN Classic

ESPN Classic is available in over 63 million homes. Its programming focuses on sports history, and “classic” games, personalities, and stories from the world of sports, such as shows from the ESPN Big Fights Library. Its documentaries and programming have won Emmy and Peabody Awards, such as for its “SportsCentury” show. Its coverage generally relates to all the major professional sports plus college football and basketball.

ESPN News

Begun in November 1996 with 1.5 million subscribers. ESPNEWS is the only 24-hour sports news network and has established itself as a major sports news and information source in more than 60 million homes.

ESPN-U

ESPN-U

ESPN-U is the 24-hour college sports TV network that specializes in college sports. It was launched in March 2005. ESPN-U has marketing agreements with colleges and universities in Kansas, Oregon and Florida. ESPN-U has college marketing agreements with universities and colleges in Kansas, Oregon and South Florida. In August 2006, ESPNU premiered ESPNU.com, a dedicated website that includes live streaming college sports events, podcasts, and other material from ESPN and elsewhere.

ESPN Regional TV

Also known as ERT or ESPN Plus, ESPN Regional Television is one of the largest TV/radio sports marketing, syndication and production companies, producing more than 900 events annually for ESPN networks, ABC, and other national, regional and local outlets. ERT is the nation’s largest syndicator of intercollegiate sports programming, and produces more than 900 college TV programs, including football, basketball, NCAA events, golf and other events. ERT also produces five ESPN-organized football Bowl games, and also the College Football Awards program. In addition, ERT is the production headquarters for ESPN-U.

ESPN Radio

ESPN Radio

ESPN Radio and affiliates comprise the nation’s largest sports radio network, providing content to more than 700 stations nationwide, including those in the 100 top markets. It has 350 full-time affiliates including owned stations in New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, Dallas, and Pittsburgh. Its programming is also available to U.S. troops in more than 175 countries through American Forces Networks. Programming includes: NBA and Major League Baseball games, college football playoffs and other coverage. An affiliate web site, ESPNRadio.com is one of the most visited online sports radio sites in the U.S., logging as many as 250,000 online listeners per month, also producing more than 35 original podcasts each week accounting for more than four million downloads per month to portable digital devices.

ESPN.comESPN.com is the leading sports web site, averaging 18 million users per month, more than any other sports website.

ESPN’s website, ESPN.com, launched in April 1995 is the leading sports website, averaging 18 million unique users per month, more than any other sports website, according to Neilsen Netratings. It produces 350-450 new videos each week, featuring daily highlights, news, interviews, and originally produced exclusive content. The site also features up-to-the-minute sports news, statistics, analysis and scores; multiple free and premium fantasy games; free online poker; live event webcasts; live chat with players, ESPN experts, sports personalities; a wide array of sports journalism including that of ESPN The Magazine.

ESPN Mobile

ESPN also provides up-to-the-minute scores, stats, news headlines, video and some exclusive programming to numerous mobile and wireless providers such as Verizon, QUALCOMM and others. It has features agreements with every major U.S. carrier and 35 international carriers. ESPN Mobile TV offers 24/7 streaming video of ESPN news, highlights, live games and events. ESPN’s wireless Internet site is the #1 wireless sports content site, generating nearly nine million unique visitors monthly.

October 9, 2006 issue of 'ESPN The Magazine' -- covers sports mostly, but sometimes a Tom Cruise story or two may also appear.

October 9, 2006 issue of 'ESPN The Magazine' -- covers sports mostly, but sometimes a Tom Cruise story or two may also appear.

ESPN Books

ESPN Books, started in 2004, is a publishing company operated by ESPN that has published about 20 books so far. ESPN Books also produces ESPN’s yearly sports encyclopedia and operates its own book club.

ESPN The Magazine

Launched in March 1998, ESPN The Magazine has a circulation base of 1.95 million. It covers a variety of sports news and offers in-depth commentary, opinion, and top photography. The magazine also includes occasional stories on celebrities and entertainment. In 2003 and 2006 it won National Magazine awards for general excellence. The magazine’s covers have also been noted by the American Society of Magazine Editors.

See also at this website, two additional stories about the history of cable TV in the U.S. — “Ted Turner & CNN, 1980s-1990s,” and “Brian’s Song: 1977-2012,” about Brian Lamb and the creation of C-SPAN. For additional sports stories and sports history, see the “Annals of Sports” category page.

Thanks for visiting — and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research and writing at this website. Thank you. — Jack Doyle

____________________________________________

Date Posted: 2 April 2008

Last Update: 22 December 2022

Comments to: jdoyle@pophistorydig.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “All Sports, All The Time, 1978-2008,”

PopHistoryDig.com, April 2, 2008.

_____________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

Al Michaels' best-selling book, "You Can't Make This Up: Miracles, Memories, and the Perfect Marriage of Sports and Television," William Morrow, 304pp. Click for copy.

Al Michaels' best-selling book, "You Can't Make This Up: Miracles, Memories, and the Perfect Marriage of Sports and Television," William Morrow, 304pp. Click for copy.Bill Rasmussen, Sports Junkies Rejoice! The Birth of ESPN, Q V Pub., November 1983.

“Bill Rasmussen,” Think Quest, library.thinkquest.org

Tom Sowa, “With Eye to Future, Ex-ESPN Chairman Looks Back,”Spokane Review (Spokane, WA), Sunday, June 6, 2004.

Lee Alan Hill, “Building a TV Sports Empire; How ESPN Created a Model for Cable Success,” Television Week, September 6, 2004.

“ESPN,” Wikipedia.org.

Stuart Evey, ESPN: Creating an Empire – The No-Holds-Barred Story of Power, Ego, Money, and Vision That Transformed a Culture, Triumph Books, September 2004. Click for copy.

Michael J. Freeman ESPN: The Uncensored History, Taylor Publishing, April 2000. Click for copy.

“ABC Unit to Buy Stake in ESPN,” New York Times, January 4, 1984.

“Top Ten Cable Networks,” Wall Street Journal, March 19, 1990.

Bill Carter and Richard Sandomir, “The Trophy In Eisner’s Big Deal,” New York Times, August 6, 1995.

Michael Eisner, Work in Progress, Random House, 1998. Click for copy.

Jeffrey Ressner, “Cable TV’s Big Fish Fight,” Time, October 2, 2005.

Howard Bloom, “The King of all Sports Media – ESPN,” Sports Business News, Wednesday, December 20, 2006.

____________________________________________