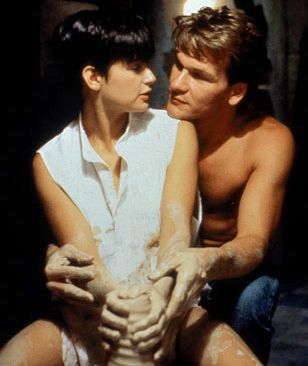

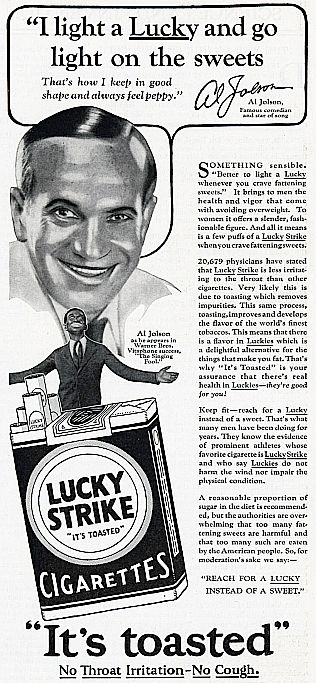

Famous 1920s’ singer & film star, Al Jolson, in Lucky Strike cigarette ad. Literary Digest, December 22, 1928.

But Jolson’s appearance in the first feature-length motion picture with synchro- nized sound and dialogue sent him to another level of stardom. In The Jazz Singer, Jolson performed six songs produced by Warner Brothers with its Vitaphone sound-on-disc system. The film’s release — quite the event in its day — heralded the rise of the “talkies” and the end of the silent film era.

Being the first popular performer to sing in a film with sound, Jolson became the equivalent of a today’s “rock star.” In fact, some would later dub him the equal of Elvis Presley when it came to the popular jazz and blues styles of that era. In any case, The Jazz Singer boosted Jolson’s career, sending him into more prosperous roles, and he would star in a series of successful musical films throughout the 1930s.

With his celebrity at its peak, the economic powers of that day soon came knocking on Jolson’s door, beseeching him to endorse their products. And none who came calling was a bigger power than the American Tobacco Co., then one of the world’s largest companies and maker of numerous tobacco products, including Lucky Strike cigarettes.

The premiere of “The Jazz Singer” in New York at the Warners Theater, October 6, 1927, the first talking motion picture and quite the event in its day.

“Precious Voice”

|

“The Tobacco Celebrities” This is one in a series of occasional articles that will focus on the history of popular celebrities from film, televi- sion, sports and other fields who have lent their names or voice, offered endorsing statements, or made personal appearances in various forms of tobacco advertising and promotion. Famous actors, sports stars and other notable personalities have been endorsing tobacco products since the late 1800s. One recent report published in the journal Tobacco Control, for example, notes that nearly 200 Hollywood stars from the 1930s and 1940s were contracted to tobacco companies for advertising. And while the stigma associated with smoking and using other tobacco products has increased in recent years as medical research evidence linking disease to tobacco has become more widely understood, the promotion of tobacco products, while not as blatant and pervasive as it once was, continues to this day in a number of countries. Not all celebrities, of course, have been involved in such endorsements, and some have worked for, or lent their names to, programs and organizations that help to prevent cigarette smoking or other tobacco-related public health problems. |

Beginning in the late ’20s, American Tobacco began a campaign to link smoking with sophistication, slimness, and “sonorous voices.” Part of this campaign in 1927 was dubbed the “Precious Voice” campaign, which dovetailed nicely with the arrival of the both the talking motion picture and the rise of radio and its commercialization. American Tobacco, in fact, spent tens of millions of dollars on radio programs that ran between 1928 and the mid-1950s; shows which also used the company’s celebrity tobacco ads. But in the late 1920s, following the release of The Jazz Singer, as “talking pictures” became all the rage, American Tobacco sought actor endorsements for its cigarettes. It also began actor and singer cigarette advertising that claimed Lucky Strike spared their throats and protected their voices. And American Tobacco ads also used another tack in 1928 — this time featuring Lucky Strike cigarettes as an alternative to fattening sweets. “Reach for a Lucky Instead of a Sweet” was the slogan that ran with this campaign in 1928-1929. Al Jolson appeared in at least one of these ads — as shown in the December 1928 ad at the top of this story. That ad ran in popular magazines of the day. Jolson is quoted in the ad’s headline saying: “I light up a Lucky and go light on the sweets. That’s how I keep in good shape and always feel peppy.” Part of the arrangement in such ads was also to have a tie-in with the film studio — in this case, for Jolson’s latest new film. Near the Lucky Strike pack in the above ad, the text reads: “Al Jolson, as he appears in Warner Bros Vitaphone success, The Singing Fool.”

Feds Take Note

In 1929, however, the federal government’s Federal Trade Commission (FTC) began to scrutinize cigarette ads and their testimonials by the famous personalities. One of the campaigns the FTC went after was American Tobacco’s “Reach for a Lucky Instead of a Sweet” campaign, and the use of that slogan. Not surprisingly, the U.S. candy industry had lobbied federal regulators to restrict American Tobacco’s use of this phrase and would also bring legal action against American Tobacco to change its ads. But the FTC also looked at the testimonials used by celebrities in the American Tobacco ads, calling them misleading. The FTC would specifically cite Jolson’s words in one endorsement where he is making several claims about the supposed benefits of smoking Luckies — similar to those used in first ad above. In the advertising, Jolson is quoted as saying, in part:

“Talking pictures demand a very clear voice… Toasting kills off all the irritants, so my voice is as clear as a bell in every scene. Folks, let me tell you, the good old flavor of Luckies is as sweet and soothing as the best “Mammy” song ever written… There’s one great thing about the toasted flavor…it surely satisfies the craving for sweets. That’s how I always keep in good shape and always feel peppy.”

The FTC also found that Jolson did not write the attributed lines himself or review it before its use, specifically citing a 1928 Lucky Strike Radio Hour broadcast of the message. Instead, Warner Brothers’ advertising manager A. P. Waxman, signed a release on Warner Brothers letterhead for text similar to what was used on air, stating that he acted on Jolson’s behalf. In November 1929, the FTC issued a cease and desist order against American Tobacco, prohibiting the use of testimonials unless written by the endorser, whose opinions were “genuine, authorized and unbiased”. In addition, American Tobacco did not acknowledge publicly in its print ads or radio broadcasts that its advertising testimonials were bought or that an advertising agency drafted them.

By the late 1930s, American Tobacco was regularly using movie-star celebrities in its ads, such as Claudette Colbert, shown here, also noting her co-staring role in the upcoming film, “Bluebeard’s Eighth Wife,” by Paramount.

American Tobacco revised the contractual language for its 1931 endorsement campaign to ensure control over the language and messaging of the testimonials, while still conforming to the FTC’s 1929 stipulations that endorsers supply the testimonial. While actors offered their opinions and declared the number of years they smoked Lucky cigarettes, they permitted Lord & Thomas, the ad agency, to write the actual testimonial — “phrased in such form as to make an effective message from the standpoint of truthfulness and advertising value.” Actors also signed revised release statements that read: “No monetary or other consideration of any kind or character has been paid me or promised me for the above statement, by [American Tobacco’s agent], or by the manufacturers of Lucky Strike Cigarettes or otherwise.” But the money was flowing to the studios, not the actors directly, a practice that would only grow in the decades ahead, as other tobacco companies began their campaigns. The studios would soon see big gains from the cross promotion in these ads, as their stars and latest movies were being touted, so they were generally happy to deal with the tobacco companies. According to the study, Signed, Sealed and Delivered: Big Tobacco in Hollywood, 1927-1951, the studios also negotiated the content of testimonials, insisted that the timing of the ads and radio appearances be coordinated with movie releases, and sometimes denied permission for deals that did not serve their interest. But all in all, it was a good deal for the studios and the tobacco companies.

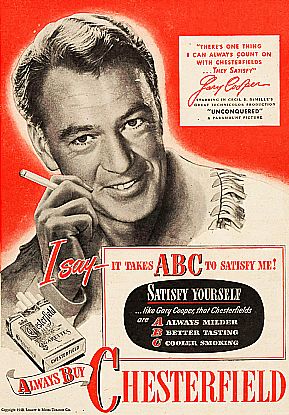

The FTC, meanwhile, in its earlier investigation of the film-star tobacco ads, had also ordered American Tobacco to disclose payments made for actor testimonials used in its advertising. However, by 1934, American Tobacco successfully removed this disclosure requirement, presumably through its lobbying of the agency. From the late 1930s through the 1940s, two thirds of the top 50 box office stars in Hollywood would endorse tobacco products in advertising. Soon, the FTC’s attempt to clamp down on the relationship between big tobacco and its Hollywood helpers was largely circumvented. Some internal film industry prohibitions on actor endorsements — briefly in effect in 1931 — would be bypassed as well. By 1937 and 1938, American Tobacco was paying to have a long list of Hollywood stars to appear in its ads, including: Gary Cooper, Claudette Colbert, Joan Crawford, Henry Fonda, Bob Hope, Carole Lombard, Ray Milland, Robert Montgomery, Richard Powell, George Raft, Edward G. Robinson, Barbara Stanwyck, Gloria Swanson, Robert Taylor, Spencer Tracy, and Jane Wyatt. The payments to stars ranged in value, in 2008 dollars, generally from $40,000 to $140,000 for each endorsement. In all, American Tobacco payed out the 2008 equivalent of some $3.2 million for actor endorsements of Lucky Strike cigarettes in print ads and radio spots in 1937-38. In fact, from the late 1930s through the 1940s, two thirds of the top 50 box office stars in Hollywood would endorse tobacco products in advertising.

By the late 1940s, Chesterfield cigarettes were the dominant brand being pitched by Hollywood celebs, here by Gary Cooper in 1948, also plugging his film, “Unconquered” by Paramount.

For additional stories at this website on advertising history see the “Madison Avenue” category page, and for celebrities, the “Celebrity & Icons” page. Thanks for visiting — and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research, writing and continued publication of this website. Thank you. — Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

_______________________________

Date Posted: 31 January 2010

Last Update: 24 January 2020

Comments to: jdoyle@pophistorydig.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Al Jolson & Luckies, 1928-1940s,”

PopHistoryDig.com, January 31, 2010.

______________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

|

Lucky Strike Radio Between the late 1920s and mid-1950s, the American Tobacco Co. spent tens of millions of dollars on radio programs that ran between 1928 and the mid-1950s; shows which also used the company’s celebrity tobacco ads. Among these programs were: The Lucky Strike Dance Orchestra, also known as the Lucky Strike Dance Hour, which aired on NBC radio from 1928 to 1931; Your Hit Parade, which ran on NBC and CBS from 1935 to 1955; Your Hollywood Parade, an hour long weekly program broadcast from the Warner Brothers studio Hollywood lot; and The Jack Benny Program, which ran from the mid-1940s to the mid-1950s. Of the program Your Holly- wood Parade, broadcast from the Warner Brothers studio lot, the authors of Signed, Sealed and Delivered: Big Tobacco in Hollywood, 1927-1951, would write: “The radio show reinforced the impression, also encouraged by the print campaign, that everyone in Hollywood smoked Lucky Strike…” In fact, on that radio program in the early 1940s, Lucky Strike “impressions” — phrases, jingles or brand name mentions of one kind or another — were being heard by listeners nearly every 30 seconds. |

K.L Lum, J.R Polansky, R.K. Jackler, and S.A. Glantz, “Signed, Sealed and Delivered: ‘Big Tobacco’ in Hollywood, 1927-1951,” Tobacco Control Journal, September 25, 2008.

Moirafinnie, “Smoke Gets In Your Eyes,” MovieMor- locks.com, May 13, 2009.

“Al Jolson,” Wikipedia.org.

Milton Moskowitz, Michael Katz and Robert Levering, “Cigarette Makers,” Everybody’s Business: The Irreverent Guide to Corporate America, Harper & Row, 1980, pp. 765-769.

John Stauber & Sheldon Rampton, “The Art of the Hustle…,” and “Smokers’ Hacks,” in Toxic Sludge is Good For You: Lies, Damn Lies and The Public Relations Industry, Common Courage Press, Monroe, Maine, 1995, pp. 17-32.

AFP- Paris, “Tobacco Giants Paid Millions to Stars in Hollywood’s ‘Golden Age’,” September 24, 2008.

Ewen Callaway, “Hollywood Cut Secret Deals to Promote Smoking,” NewScientist.com, September 25, 2008.

“Tobacco Companies Paid Movie Stars Millions in Celebrity Endorsement Deals,” EScienceNews.com, Thursday, September 25, 2008

Tracie White, “Tobacco-Movie Industry Financial Ties Traced to Hollywood’s Early Years in Stanford/UCSF Study,” Stanford.edu, September 24, 2008.

“Not a Cough in a Carload,” Extensive On-Line Exhibit of Tobacco Ads, Lane Medical Library & Knowledge Management Center, Stanford.edu.

A. M. Brandt, The Cigarette Century: The Rise, Fall, and Deadly Persistence of the Product That Defined America., Basic Books, 2007.

R. Kluger, Ashes to Ashes: America’s Hundred-Year War, the Public Health, and the Unabashed Triumph of Philip Morris, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1996.

_____________________________