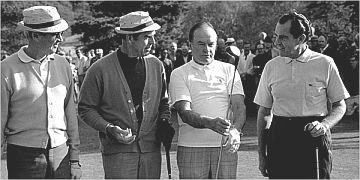

Rat Pack members without Joey Bishop, from left: Peter Lawford, Frank Sinatra, Sammy Davis, Jr., and Dean Martin. Photo, Life magazine, 1960. Click for Life “rat pack” edition.

Rat Pack members without Joey Bishop, from left: Peter Lawford, Frank Sinatra, Sammy Davis, Jr., and Dean Martin. Photo, Life magazine, 1960. Click for Life “rat pack” edition. “The Jack Pack” was the name briefly attributed to a famous group of 1960s entertainers who supported U.S. Senator John F. “Jack” Kennedy (JFK) in his 1960 run for president. “The Jack Pack” moniker was actually a variant of “The Rat Pack,” a nickname for a coterie of Hollywood stars and Las Vegas entertainers that included: Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, Sammy Davis, Jr., Joey Bishop and Peter Lawford.

In 1960, this group was temporarily dubbed “the Jack Pack” by Sinatra when they worked in various ways to support Kennedy’s election bid. Kennedy had socialized with Sinatra and the group on occasion and liked the camaraderie, which later turned to political and financial support on his behalf.

What follows here is Part 1 of a two-part story featuring “Jack Pack” history, primarily with Frank Sinatra at the center. Part 1 covers Sinatra’s politics, the Rat Pack scene in Las Vegas, and some of the group’s friends during Kennedy’s presidential run – mostly from 1958 through Kennedy’s election in November 1960.

Part 2 of this story – a separate post at this website – begins with JFK’s presiden-tial inauguration in January 1961, and also covers selected Sinatra, Rat Pack, and Kennedy Administration history through JFK’s assassination in November 1963, plus a few related outcomes beyond those years. First, some background on the Rat Pack.

In the late 1940s, film star Humphrey Bogart had a loyal group of friends and drinking buddies in an area of Los Angeles known as Holmby Hills. Then Hollywood rookie, Frank Sinatra, who had moved his family into that area in 1949, became a nearby neighbor to Bogart, and then a member of his group. Legend has it that Bogart’s wife and film star Lauren Bacall, saw the drunken crew of friends all together one night at a casino and remarked that they looked like a “rat pack.”

Life magazine “rat pack” photo, from left: Peter Lawford, Sammy Davis, Jr., Frank Sinatra, Joey Bishop, and Dean Martin.

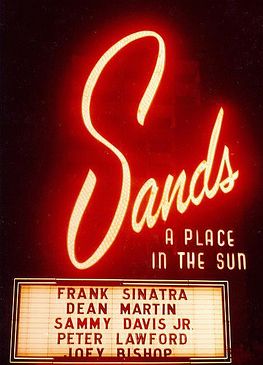

Life magazine “rat pack” photo, from left: Peter Lawford, Sammy Davis, Jr., Frank Sinatra, Joey Bishop, and Dean Martin. Sometime after Bogart passed on in 1957, Sinatra established his own inner group of cavorting buddies, all from Hollywood and the world of enter- tainment. Sinatra’s “Rat Pack” – not initially called that at first – came about gradually from their work in Las Vegas and their Hollywood contacts. The late-1950s-early-1960s “Rat Pack” era appears to have begun in Las Vegas in January 1959 when Sinatra and Dean Martin – then performing separately at The Sands lounge and casino – began appearing in each other’s acts. Sinatra knew Joey Bishop from the early 1950s on the east coast, when Bishop performed at the Latin Quarter in Manhattan. He later asked Bishop to open for him at Bill Miller’s Riviera club in Fort Lee, New Jersey, and soon thereafter Bishop was regularly opening for Sinatra, becoming known as “Sinatra’s comic.” Bishop also began appearing in first-rate clubs even when Sinatra was not on the bill.

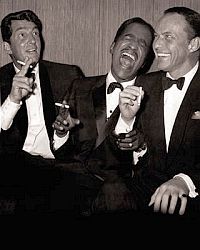

Dean Martin, Sammy Davis & Frank Sinatra having a good time.

Dean Martin, Sammy Davis & Frank Sinatra having a good time. Sinatra was singing with Tommy Dosey’s band in 1941 when he first met Sammy Davis, Jr., then an aspiring dancer with the Will Mastin Trio. They reconnected some time later after Sammy was discharged from the U.S. Army, and Sinatra would later help Davis in his career. Peter Lawford and Sinatra had worked in a few films together in the 1940s, but Sinatra came to know him much better as Jack Kennedy’s brother-in-law. More on that relationship a bit later.

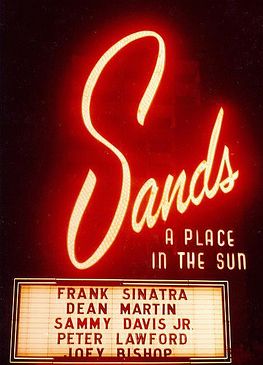

By the early 1960s in any case, the Rat Pack became known for its multiple-person stage acts – with all five of the principals on stage together, plus others occasionally. The Sands, in fact, would sometimes advertise the horseplay on its outdoor marquee with billings such as: “Dean Martin – Maybe Frank – Maybe Sammy.”

Others from Hollywood and the entertainment world would also occasionally appear and/or hang out with the Rat Pack group. Shirley MacLaine, for example who starred with Sinatra and Dean Martin in 1959’s Some Came Running, would also become a Rat Pack “associate” from time to time.

Dean Martin on stage at the Sands in Las Vegas, where Rat Pack performances drew large crowds of celebrities & VIPs from Hollywood and elsewhere.

Dean Martin on stage at the Sands in Las Vegas, where Rat Pack performances drew large crowds of celebrities & VIPs from Hollywood and elsewhere. The core group of the Rat Pack, however – consisting of Sinatra and his co-performing buddies – basically set up shop in Las Vegas during the late 1950s and early 1960s. Las Vegas at the time was still growing, and the Rat Pack helped bring in the notice, the visitors, and the money. The Rat Pack’s nightclub act evolved into an entertaining and popular song, dance and comedy act with a lot of cutting up on stage, a rolling bar of alcoholic beverages, along with a measure of social commentary thrown in from time to time.

The Rat Pack “schtick” was part Vaudeville, part Hollywood, and part “bad boys.” It became a unique stage genre and vintage Las Vegas. But it only lasted a few years before it burned out and was eclipsed by a fast-changing cultural scene. In its day, however, the Rat Pack did the trick and fit the national mood. Musically and culturally, it occupied the transition period between the first surge of rock `n roll in the 1950s by the likes of Chuck Berry, Elvis Presley, and Buddy Holly – music which Sinatra initially derided – and the arrival of the Beatles in 1964.

Rat Pack stage act with rolling beverage cart, early 1960s.

Rat Pack stage act with rolling beverage cart, early 1960s. In addition to their stage act, the Rat Pack

compadres also made films together – some shot in Las Vegas.

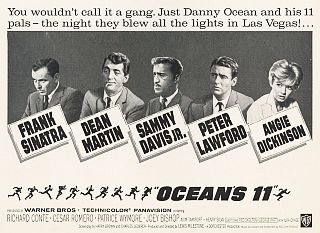

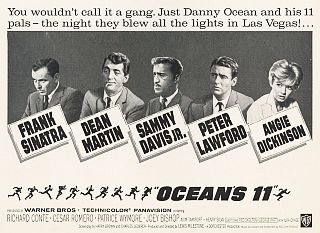

Ocean’s Eleven of 1960 was among the more famous of the Rat Pack films, but there were also nearly a dozen others. Through the early-1960s period, Sinatra and his Rat Pack group reigned supreme in contemporary culture; they became the “cool guys” of their generation, bringing a good share of business to both the Las Vegas nightclub scene and Hollywood’s box office. Their network of contacts, friends, and business partners ranged across Hollywood, Vegas, and beyond, including some underworld figures like Sam Giancana of Chicago and also various Hollywood stars such as Tony Curtis, Marilyn Monroe, Janet Leigh, Angie Dickinson, and others.

Rat Pack film, "Sergeants 3," 1962.

Rat Pack film, "Sergeants 3," 1962. The “Rat Pack network” of that era could also be a potent fundraising and vote-getting machine, a fact not lost on Kennedy family patriarch, Joseph P. Kennedy, an old hand when it came to Hollywood stars and the film business. The Rat Pack in 1960 became intertwined with the Kennedy family – especially by way of Peter Lawford’s marriage to Jack Kennedy’s sister, Patricia.

However, for some Rat Packers like Dean Martin, politics was a bit of a side show, not to be taken too seriously. Martin, in fact, had met and caroused with a young Congressman Jack Kennedy in Chicago one night 1948 when he and Jerry Lewis were working as a comedy team at the Chez Paree club – a meeting that left “Dino” unimpressed.

But in 1960, Jack Kennedy and politics became very central to Rat Pack leader, Frank Sinatra.

Sinatra’s Politics

Frank Sinatra with then-U.S. Senator John F. Kennedy outside of The Sands hotel in Las Vegas, NV, Feb 1960, when Kennedy stayed there during a campaign swing.

Frank Sinatra with then-U.S. Senator John F. Kennedy outside of The Sands hotel in Las Vegas, NV, Feb 1960, when Kennedy stayed there during a campaign swing. Frank Sinatra, from his days as a young boy growing up in New Jersey, had been involved in politics by proximity if nothing else. His mother had worked as a Democratic Party committee woman in New Jersey, and as a boy he marched in political parades. But once he became

famous as a young singer in the 1940s and caught the national limelight, politicians soon noticed and sought him out. In 1944 he received an invitation to the White House from Franklin Roosevelt, then in his third term. At the time, Roosevelt was under fire from conservatives in the press, especially the Hearst newspapers owned by William Randolph Hearst. Sinatra, too, had also received some unflattering ink from the Hearst papers. At his meeting with FDR, the two shared stories with Sinatra giving the president some insight on the music business. But Sinatra was awe struck by the White House attention and couldn’t believe how far he’d come. Roosevelt, he told the press, was “the greatest guy alive today, and here’s this little guy from Hoboken shaking his hand.”

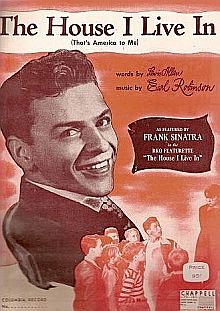

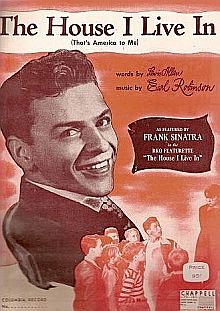

Sheet music cover for song, “The House I Live In,” from the RKO short film of the same name starring Frank Sinatra, 1940s. Chappell & Company. Click for digital recording.

Sheet music cover for song, “The House I Live In,” from the RKO short film of the same name starring Frank Sinatra, 1940s. Chappell & Company. Click for digital recording. Sinatra supported FDR and contributed to the Democratic Party. He also appeared at the party’s rally at Madison Square Garden that campaign season. He would also become a close friend to Eleanor Roosevelt and years later would invite her to appear on his television show. Sinatra was also active in certain causes, particularly fighting racism and segregation.

In 1945, he appeared in, produced, and won an Oscar for the 1945 short film and song, The House I Live In – a plea for ethnic and religious tolerance. In the film role, Sinatra intercedes to protect a Jewish kid being attacked by a gang of bullies. Sinatra appeals to them through the lyrics of the film’s song: “The faces that I see / All races and religions / That’s America to me.” This short film was scripted by Albert Maltz, a person who would later come into Sinatra’s life when he became involved with Jack Kennedy.

Sinatra would sing “The House I Live In” on various occasions during his career, and sometimes at political gatherings, as he did at a 1956 Democratic party rally in Hollywood. Sinatra would also put his career at risk at times when he refused to play clubs and hotels that discriminated against blacks. Actress Angie Dickinson, who sometimes cavorted with the Rat Pack, would later call Sinatra, “a very powerful, subtle force in civil rights…[and] not only in Las Vegas.”

Frank Sinatra and Ava Gardner at Los Angeles political rally for presidential candidate Adlai Stevenson, 1955.

Frank Sinatra and Ava Gardner at Los Angeles political rally for presidential candidate Adlai Stevenson, 1955. After World War II, Sinatra became publicly associated with left-wing groups and supported organizations that were later identified by Congress as Communist front groups during inquiries by the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). Though Sinatra was named in some committee documents, he was never brought before HUAC.

The Hearst newspapers, however, gave him a rough time over his left-wing involvements. And Sinatra’s career, like others in Hollywood at the time, suffered.

According to one account, Columbia records asked Sinatra to return advance money and MGM released him from a film contract. He was also dropped from his radio show. But Sinatra remained politically involved.

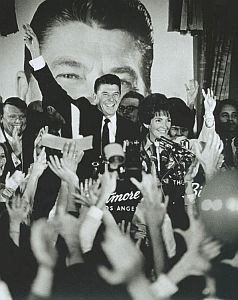

Frank Sinatra with former President Harry Truman (center) and toastmaster George Jessel in November 1957 at Jefferson-Jackson Day Dinner and fundraiser, Biltmore Hotel, Los Angeles.

Frank Sinatra with former President Harry Truman (center) and toastmaster George Jessel in November 1957 at Jefferson-Jackson Day Dinner and fundraiser, Biltmore Hotel, Los Angeles.

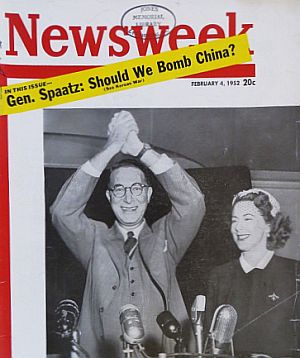

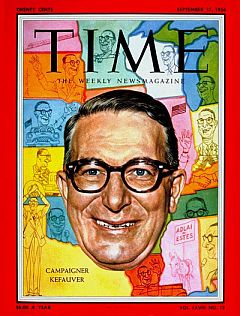

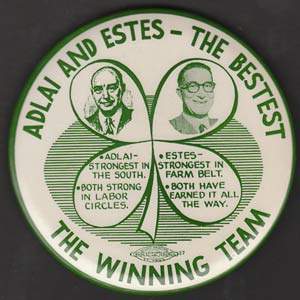

In 1947, he urged former FDR vice president Henry Wallace to run for President, which Wallace did as a Progressive Party candidate. But in 1948, Sinatra also campaigned for the re-election of FDR successor, Harry S. Truman. In 1952 and 1956, he supported the unsuccessful presidential bids of Democratic nominee Adlai Stevenson. He campaigned for Stevenson in 1956, also the year he came into contact with the Kennedy family for the first time. At the 1956 Democratic convention he sang the National Anthem, but remained at the convention to observe some of the politicking that occurred after Adlai Stevenson had thrown open the vice presidential nomination to the full convention.

A young new Senator, John F. Kennedy, was making a run for that spot. Kennedy lost to Senator Estes Kefauver, but Sinatra had watched the Kennedy machine in operation on the convention floor. From that point on Sinatra took an interest in the rising young senator he believed was heading places. But it was British actor Peter Lawford, a subsequent “rat pack” member, who would help Sinatra become much closer to Kennedy and the Kennedy family.

Lawford-Kennedy

Patricia Kennedy Lawford and Peter Lawford, 1960s.

Patricia Kennedy Lawford and Peter Lawford, 1960s. Frank Sinatra and Peter Lawford had known each other from working in Hollywood, dating to the 1947 musical comedy film,

It Happened in Brooklyn, in which they both appeared. But their paths crossed again in the early 1950s under somewhat less cordial circumstances. Sinatra had been angered by a 1953 gossip column account of Lawford’s meeting with

Ava Gardner, who Frank had recently broken up with. Some bad blood reportedly flowed between the two over the incident. Sinatra later discovered he’d overreacted to the Ava Gardner story, and he and Lawford more or less went their separate ways. Lawford, meanwhile, married Patricia Kennedy in 1954, the sister of then U.S. Senator John F. Kennedy.

In August 1958, at a dinner party at Gary Cooper’s home, Sinatra came to know Peter and Pat Kennedy Lawford somewhat better. By New Year’s Eve 1958, the Lawfords were celebrating at a private party with Sinatra at Romanoff’s in Beverly Hills, a popular spot with Hollywood stars.The Lawfords soon had a regular bedroom at Frank Sinatra’s Palm Springs place, where they made frequent visits. They were all together that night, seated at Sinatra’s table with Natalie Wood and Robert Wagner. In July 1959, the same group would return to Romanoff’s along with Dean Martin and others at a Sinatra-sponsored 21st birthday party for Natalie Wood. The friendship between Sinatra and Lawfords grew to the point where the Lawfords frequently visited Sinatra’s Palm Springs estate, making the 120-mile drive there from Los Angeles on many weekends. In fact, the Lawfords had a regular bedroom at Sinatra’s place where they kept clothing for return visits. Sinatra and the Lawfords also traveled to Europe together on vacation. Pat Lawford was so charmed by Sinatra she middle-named her daughter “Frances.” Sinatra also helped Peter Lawford land film work in Hollywood, including a role in the 1959 film Never So Few. The two men also became partners in a Beverly Hills restaurant named Puccini’s and Lawford soon became a full-time member of Sinatra’s Rat Pack in Las Vegas.

Frank & Jack

Kennedy’s dramatic bid for the VP slot at the 1956 Democratic Convention – and his charisma – had been seen by millions of TV viewers.

Kennedy’s dramatic bid for the VP slot at the 1956 Democratic Convention – and his charisma – had been seen by millions of TV viewers. Some sources date Frank Sinatra’s first meeting with Jack Kennedy to 1955 when Kennedy attended a Democratic Party rally where Sinatra had also appeared. And in 1956, as mentioned earlier, Sinatra was quite taken with what he saw in the young Kennedy seeking the VP slot at the Democratic convention that year. But through the Lawfords, Sinatra came to know Jack Kennedy more on a personal level. The Lawfords owned a large beach front house in Malibu – the former mansion of Hollywood mogul Louis B. Mayer – a place, it would turn out, where “rat packers,’ Kennedy campaigners, and other political and Hollywood “glitterati” would gather occasionally for parties and other events.

Jack Kennedy and Sinatra appear to have spent time together in the summer of 1958, whether at the Lawfords or elsewhere. Some sources have Sinatra endorsing Kennedy for president as early as October 1958, though Kennedy was more than a year away from formally announcing his candidacy at that point.Sinatra visited Kennedy at his Mayflower Hotel “hide away” suite in D.C., and Kennedy, when traveling in the U.S. West, would sometimes visit Sinatra. Sinatra was also quoted in the press about that time calling the young Senator “a friend of mine.” Meanwhile, on trips east, Sinatra would sometimes visit Kennedy in Washington, D.C. at a “hide-away” suite that Kennedy kept at the Mayflower Hotel where he would have dinner parties for celebrities and private guests. Likewise, Kennedy, when traveling west on political business, would sometimes visit Sinatra. In early November 1959, after a Democratic fundraiser in Los Angeles, JFK and his aide Dave Powers were Sinatra’s guests at his Palm Springs estate for a couple of nights. On that visit, before coming to Palm Springs, Sinatra and JFK had earlier attended a Democratic Party fundraiser in Los Angeles and had dined at Pucinni’s restaurant in Beverly Hills – the restaurant owned by Sinatra and Peter Lawford. Kennedy and Powers stayed at Sinatra’s Palm Springs house for two nights on that visit. Reportedly, after Kennedy’s stay there, Sinatra began calling the room JFK had used “the Kennedy room” and later had a nameplate put on the door noting “John F. Kennedy Slept Here.” JFK’s father — clan patriarch and former Ambassador, Joseph P. Kennedy — also stayed at Sinatra’s place on at least one occasion during 1959-1960. But JFK at this point, in late 1959, was a recently re-elected U.S. Senator, not yet a formal presidential candidate.

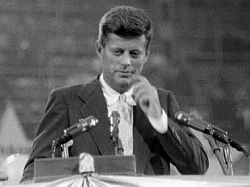

JFK announcing his presidential bid, U.S. Senate Caucus room, January 2, 1960.

JFK announcing his presidential bid, U.S. Senate Caucus room, January 2, 1960. On Saturday, January 2, 1960 at the Senate Caucus room in Washington, D.C., Kennedy officially announced his candidacy for the Democratic presidential nomination. Kennedy had already been campaigning, of course, meeting with party officials and traveling the country. But after his formal announcement, and a January 14th speech at the National Press Club in Washington, Kennedy’s campaign would begin to target primary election states and other locations where he needed to improve his standing. One early campaign stop Kennedy made was in New Hampshire, where the first primary election would be held in March.

On Monday, January 25, 1960, Kennedy and wife Jackie, visited Nashua, New Hampshire, one of the state’s larger towns. On that wintry afternoon, Kennedy walked down Main Street by himself and went into several local stores, shaking hands as he went. One of the shop owners gave Kennedy a pair of golashes to wear, as it was pretty slushy in the streets that day. It was a different era in primary politics then, as Kennedy had no entourage of body guards and handlers. Local folks were meeting him face to face. At one point, as he rounded the corner of Main and West Pearl streets in Nashua, continuing to shake hands, he made he way to one of the town’s downtown landmarks, Miller’s Department Store. At about that point he was joined by his wife, Jackie, and put his arm around her and they continued down the street, arm-in-arm.

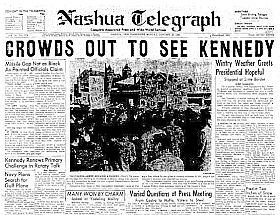

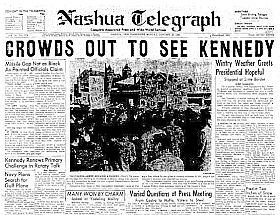

Kennedy headlines from Nashua, New Hampshire, January 1960.

Kennedy headlines from Nashua, New Hampshire, January 1960. There was a rally that day at the Nashua City Hall Plaza, with participants in winter coats holding Kennedy placards as the candidate told the crowd he was running for president. Kennedy would also meet and be photographed with City Hall employees that day, and give a talk at the local Roatary Club as well. The next day in

The Nashua Telegraph newspaper, the Kennedy visit was front-page news, as would be the case in other towns and cities as Kennedy campaigned that year for his party’s nomination. “Crowds Out To See Kennedy,” said the headline. And from that point on, it was regular campaigning, sometime with his wife Jackie along, and/or other members of the Kennedy clan.

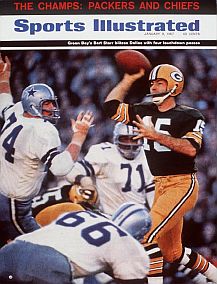

The Sands marquee, 1960, highlighting Rat Pack appearance. Click for 2020 book on The Sands.

The Sands marquee, 1960, highlighting Rat Pack appearance. Click for 2020 book on The Sands.

Las Vegas

Frank Sinatra and his Rat Pack, meanwhile, began filming the original Ocean’s Eleven movie, a film about a plot to rob several Las Vegas casinos. While filming, Rat Pack members would also perform in the Copa Room at The Sands, doing two or more stage shows each night and sometimes partying with friends thereafter into the wee hours. One famous run of their show – from January 26 through February 16, 1960 – was billed the “Summit at the Sands,” a title that played on an international summit meeting in Paris at the time between President Dwight Eisenhower, Russia’s Nikita Khrushchev, and French President Charles De Gaulle. The Rat Pack “summit” was an “anything goes” stage act of song, dance, and cutting up that became quite popular.

The Sands act with Sinatra and his Rat Pack drew high-rolling and well-known Hollywood royalty – actors, actresses, and producers such as: Lucille Ball, Desi Arnaz, Kim Novak, Jack Benny, Cole Porter, Red Skelton, Lauren Bacall, Kirk Douglas, Cary Grant, Rosalind Russell, Gregory Peck, Cyd Charisse, Peter Lorre, and others. Sinatra, who had been singing at The Sands since 1953, already had a Hollywood following. “He drew all the big money people,” Las Vegas lounge singer Sonny King would later say of Sinatra. “Every celebrity in Hollywood would come to Las Vegas to see him, one night or another.” Sinatra and the Rat Pack, in fact, are given credit in some quarters for putting Las Vegas on the “big time” entertainment map, and helping spawn the frenetic economic growth and building boom that occurred there through the 1960s and beyond. At one point in February 1960 – at the height of the Rat Pack’s “Summit” shows – the Sands had received eighteen thousand reservation requests for its two hundred rooms.

Kennedy Visit

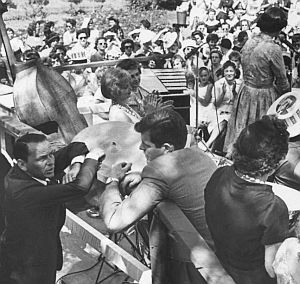

JFK meeting Rat Pack members & others outside the Sands Hotel, Las Vegas, Feb 1960. From left, clockwise: film director Lewis Milestone (back turned) Dean Martin left of Milestone, shaking hands with JFK, Buddy Lester, Joey Bishop center, Sammy Davis, Jr., partially hidden by Kennedy's arm, Kennedy, and Frank Sinatra.

JFK meeting Rat Pack members & others outside the Sands Hotel, Las Vegas, Feb 1960. From left, clockwise: film director Lewis Milestone (back turned) Dean Martin left of Milestone, shaking hands with JFK, Buddy Lester, Joey Bishop center, Sammy Davis, Jr., partially hidden by Kennedy's arm, Kennedy, and Frank Sinatra. In early 1960, one of Jack Kennedy’s part-campaign/ part-recreation visits was to Las Vegas, Nevada, where he would hook up with his friend, Frank Sinatra. On Sunday, February 7, 1960, the candidate and his entourage – including a young Ted Kennedy, then Western states coordinator for the campaign – were stumping through the American West for political support and fundraising before the big eastern primaries were to begin. They set up shop in the Sands Hotel, holding press conferences there and fundraisers, but also taking in the stage shows of Frank Sinatra and friends during their stay. Whenever Jack Kennedy came to a show, he was usually seated up front near the stage. And Sinatra, at some point during the act, would single him out for recognition. “Ladies and gentlemen,” he would say with microphone in hand, gesturing toward Kennedy, “Senator John F. Kennedy from the great state of Massachusetts, the next President of the United States.” Sinatra would often add laudatory lines, calling him “one of the brightest persons here or anywhere…” Kennedy would rise briefly to a standing ovation from the audience.

Judith Campbell, in earlier photo, who was in her late 20s when she first met John F. Kennedy.

Judith Campbell, in earlier photo, who was in her late 20s when she first met John F. Kennedy. There were also a few private gatherings at the Sands between the Kennedy campaign group, Sinatra’s Rat Pack group, and various Sinatra friends during JFK’s February visit. On the evening of February 7, 1960, they gathered for dinner at Frank Sinatra’s table in the Garden Room. Among Sinatra’s guests that evening was a woman in her late 20s named Judith Campbell, who was introduced to Senator Kennedy and his entourage. Campbell was formerly married to actor William Campbell, and for a time had been seeing Frank Sinatra. Campbell joined the group and sat next to Ted Kennedy. Jack Kennedy sat directly across from her. Campbell would later recall Teddy as a rosy-cheeked young man, “who was very good looking” and a great teaser, with “eyes that never stopped flirting.” But Campbell, according to her own later account of that evening, was more taken with the charm, sophistication, and “plain likability” of Jack Kennedy. The following day, Jack Kennedy invited Judith Campbell for lunch on the patio of Frank Sinatra’s suite at the Sands. Kennedy would later rendevous with Judith Campbell in New York in early March prior to the New Hampshire primary.

Years later, there would be all manner of reports and allegations about Kennedy meetings with Campbell and other women, some of whom were introduced to Kennedy by Frank Sinatra and/or Peter Lawford, including Marilyn Monroe.

Years later, there would be all manner of reports and allegations about Kennedy meetings with Campbell and other women, some of whom were introduced to Kennedy by Frank Sinatra and/or Peter Lawford, including Marilyn Monroe. FBI files would also include reports of showgirls visiting and/or partying with Kennedy and his entourage at the Sands in February 1960. Still other reports and books mention possible Kennedy-female liaisons at the Cal-Neva resort at Lake Tahoe, Nevada, a resort part owned by Sinatra and frequented by Rat Pack members and friends. Some reports also note an effort by the Kennedy campaign in 1960 to “clean things up” after the Sands visit (and possibly others) to collect all available photographs, etc., lest they become public. On the topic of JFK partying and female companions there is an extensive, but not always credible collection of books, magazine stories, and other sources found on-line and elsewhere.

JFK shaking hands with Jack Entratter, manager & entertainment chief at the Sands, February 1960.

JFK shaking hands with Jack Entratter, manager & entertainment chief at the Sands, February 1960. But on Kennedy’s February 1960 swing West, and during his stay at The Sands, he did quite well by most accounts. Beyond the introduction to Campbell, Kennedy left the Sands, according to one account, with “satchels full of cash,” referring to fundraising gains made in part through Sinatra’s friends and connections, including the owners of the The Sands hotel and casino. Frank Sinatra by this time was well on board to help JFK win his party’s nomination and the national election beyond. He would work hard for Kennedy throughout 1960. And while Hollywood and politics had certainly mingled before, this was something of a new mixture between nationally-popular entertainment titans and a rising political star. Sinatra, in particular, pulled out all the stops for his new political friend, and apart from any personal advantage he stood to gain from the association, Sinatra appears to have sincerely believed that Jack Kennedy would be good for the country.

Record label for Kennedy campaign song, “High Hopes,” by Frank Sinatra, recorded, Feb 1960.

Record label for Kennedy campaign song, “High Hopes,” by Frank Sinatra, recorded, Feb 1960.

Among other things, Sinatra lent his voice to the Kennedy campaign. He refashioned one of his earlier songs for Kennedy campaign use – “High Hopes” – a song first popularized by Sinatra in the 1959 film, A Hole in the Head, a comedy directed by Frank Capra in which Sinatra, Edward G. Robinson, Eleanor Parker, Keenan Wynn, and others appeared.

The original song was written by Jimmy Van Heusen with lyrics by Sammy Cahn, who also helped to rework the new version for the Kennedy campaign.

The original “High Hopes” had been a hit song, featured with a children’s choir and lyrics that described animals doing seemingly impossible acts. The song appeared on pop music charts of its day, was nominated for a Grammy, and also won an Oscar for Best Original Song at the 32nd Academy Awards — all of which made it a highly recognizable tune.

|

“High Hopes”

JFK Version, 1:49

Everyone is voting for Jack.

‘Cause he’s got what all the rest lack.

Everyone wants to back, Jack.

Jack is on the right track.

‘Cause he’s got High Hopes!

He’s got High Hopes!

1960’s the year for his High Hopes!

Come on and vote for Kennedy.

Vote for Kennedy,

and we’ll come out on top!

Oops! There goes the opposition, ker…

Oops! There goes the opposition, ker…

Kerplock!

K-E-double N-E-D-Y

Jack’s the nation’s favorite guy.

Everyone wants to back, Jack.

Jack is on the right track.

‘Cause he’s got High Hopes!

He’s got High Hopes!

1960’s the year for his High Hopes!

Come on and vote for Kennedy

Vote for Kennedy,

Keep America Strong

Kennedy, he just keeps rolling along

Kennedy, he just keeps rolling along

Kennedy, he just keeps rolling along

Vote for Kennedy !

_______________________

Listen to full song at JFK Library.

|

Sinatra recorded a special promotional 45rpm version of “High Hopes” in February 1960 for use on the campaign trail, throughout key primary states, and into the general election. This tune, with special “elect-Jack-Kennedy” lyrics, and backed by a chorus version of “all the way,” pretty much became the JFK campaign theme song. Frank Sinatra, however, wasn’t always available to make personal appearances on behalf of Kennedy — though he did his share. Still, his presence permeated the campaign nationwide by virtue of this campaign song. And on some occasions, “High Hopes” received a little bit of extra help.

Juke Box Fix

Leading up to the West Virginia Democratic primary election in May, juke boxes in that state, which were controlled through an organized crime network, were updated with copies of the “High Hopes” recording.

Kennedy aides also went through the state paying tavern and restaurant owners a small stipend to assure that the new jukebox version of “High Hopes” was played frequently. Beyond West Virginia, the special recording was widely circulated and used during Kennedy’s election run, played at campaign rallies, on jukeboxes, and also heard in some TV ads. The Sinatra song for JFK was heard all across the country.

During the primary election season, however, Kennedy handlers became nervous about Sinatra and the Rat Pack becoming too overtly connected to the campaign, as Democratic rivals, including Hubert Humphrey and Lyndon Johnson, would try to cast those associations in a negative light.

So, Sinatra and other Rat Packers did limited public campaigning for Kennedy during the primaries. And not long after the New Hampshire primary– in which Kennedy had won the state’s Democratic Party nomination on March 8, 1960 – there came some controversy with Frank Sinatra.

The Maltz Affair

1950, photo from film clip, Albert Maltz.

1950, photo from film clip, Albert Maltz. In February 1960, Sinatra planned to hire Albert Maltz to write the screenplay for a film he was making about an army deserter during WWII using the title, the

Execution of Private Slovick. But Maltz was one of the famous “Hollywood Ten” – alleged communist party members who appeared before the House UnAmerican Activities Committee in November 1947. Maltz was one of those jailed in 1951 for contempt of Congress, refusing to tell the committee whether he had ever been a member of communist organizations. When word of Sinatra’s plan to use Maltz was reported by the

New York Times on March 12, 1960, the reaction, especially in some conservative corners, began to reach into Sinatra’s involvement with the Kennedy campaign. Sinatra fought back, claiming his critics were hitting “below the belt.” At one point he even took out an ad in the Hollywood trade papers saying he was his own man and could hire who ever he wanted. General Motors, however, then a giant economic power, had been lined up to sponsor some of Frank’s TV specials, and threatened to withdraw over the Maltz connection.

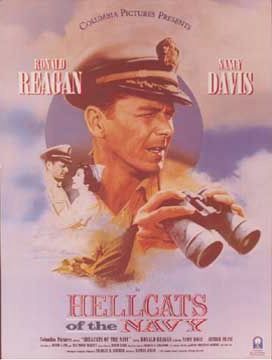

Frank Sinatra & Elvis Presley on Sinatra’s May 1960 “Welcome Home Elvis” TV special. Click for DVD.

Frank Sinatra & Elvis Presley on Sinatra’s May 1960 “Welcome Home Elvis” TV special. Click for DVD. One of Sinatra’s planned TV specials at the time was to “welcome home” Elvis Presley, the young rock ’n roll star whose earlier U.S. Army enlistment was then ending. But Presley’s manger, Colonel Parker, also called Sinatra, saying Presley might have to pull out. Then the Catholic Church, including a Boston cardinal, began suggesting that if JFK were perceived as soft on communism, this might cost him some Catholic votes. With that, patriarch Joe Kennedy weighed in, telling Sinatra he felt the controversy would hurt Jack’s presidential bid. In early April 1960s, Sinatra finally agreed let Maltz go, but he paid him in full. Sinatra also had a bit of dust up with fellow Hollywood star and then Richard Nixon supporter John Wayne over the Maltz affair. Wayne and Sinatra had attended a benefit dinner at the Moulin Rouge club in Los Angeles later that spring, and they nearly came to blows over Maltz, according to one account. The incident arose over earlier negative comments Wayne had made about Kennedy and Sinatra’a hiring of Maltz. Wayne reportedly told a reporter, “I wonder how Sinatra’s crony, Senator John F. Kennedy, feels about Sinatra hiring such a man.” In any case, neither Kennedy nor Sinatra appeared mortally wounded by the Maltz affair. Sinatra, for his part, was then having a good run on broadcast television. His “Welcome Home Elvis” TV special – the final show in a series of four successful Sinatra TV specials – was broadcast in May 1960, and according to reports at the time it earned “massive viewing figures.” That special, and others that preceded it, also typically included other Rat Pack members, Sammy Davis Jr., Joey Bishop, Peter Lawford, and at the Elvis show, Sinatra’s daughter, Nancy.

Wisconsin

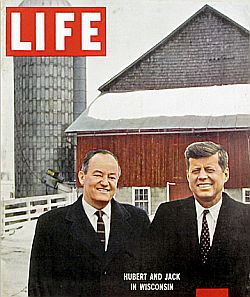

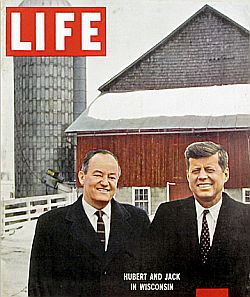

Hubert Humphrey and John F. Kennedy shown on Life magazine cover, March 28, 1960.

Hubert Humphrey and John F. Kennedy shown on Life magazine cover, March 28, 1960. Kennedy, meanwhile, in March and April of 1960, was facing a formidable challenger in the Wisconsin Democratic Presidential primary, fellow U.S. Senator Hubert Humphrey, a popular liberal from Minnesota. The two senators had squared off in Wisconsin. Both men had campaigned extensively in the state. Kennedy used his family members and wife, Jackie, to help cover the state. Kennedy sisters Eunice, Jean and Pat were there, as were brothers Bobby and Ted. The March 28, 1960 edition of

Life magazine did a feature piece on the two candidates spread over several pages with photos of their respective campaigns in the state. There was also a small photo of Frank Sinatra included in

Life’s story with the caption “voice Sinatra,” referring to his Kennedy “High Hopes” recording, but also mentioning that he did not appear in the state for Kennedy in person. On April 5, 1960, the day of the primary election, Kennedy emerged the victor, beating Humphrey by a count of 478,118 to 372,034. It was an important primary win for Kennedy. However, Kennedy’s margin of victory in Wisconsin had came mostly from heavily Catholic areas, and that left party bosses unconvinced of his appeal to non-Catholic voters. So the next primary state of West Virginia – a heavily Protestant state where Kennedy would also face Humphrey, but where anti-Catholic bigotry was said to be widespread – would be crucial.

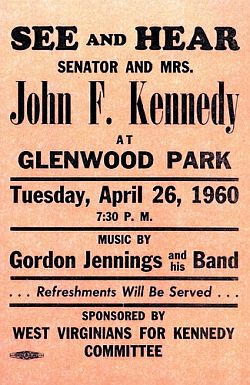

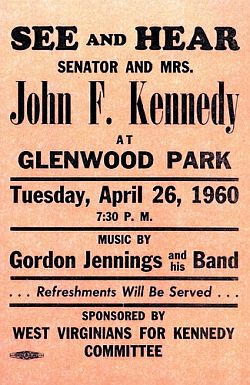

Poster announcing April 26, 1960 campaign event with Senator John F. Kennedy and his wife, Jackie, during West Virginia primary.

Poster announcing April 26, 1960 campaign event with Senator John F. Kennedy and his wife, Jackie, during West Virginia primary.

West Virginia

West Virginia turned out to be a critical state that Kennedy needed to win for the Democratic Presidential nomination. Without a primary win there, he faced the prospect of a brokered convention decided by Democratic Party bosses where competing candidates such as Lyndon B. Johnson, Adlai Stevenson, and/or Hubert Humphrey might do quite well. Initially, Kennedy thought he would not need to run in the West Virginia primary, as earlier polling in the state in 1958 had shown him to be well ahead of the likely Republican nominee, Richard Nixon. It also appeared there would be no Democratic challenger to run in the primary. But after Hubert Humphrey decided to run there, another Lou Harris Poll found Kennedy running well behind Humphrey. Kennedy’s Catholic religion also became a factor in West Virginia. But on May 8th, two days before the election, Kennedy’s campaign brought Franklin Roosevelt’s son into the state to help, and in a radio broadcast paid for by the campaign, FDR, Jr. asked JFK how his Catholicism would effect his presidency. Kennedy replied that taking the oath of office required swearing on the Bible that the president would defend separation of church and state. Any candidate that violated this oath, Kennedy said in the broadcast, not only violated the Constitution but “sinned against God.”Kennedy patriarch Joseph Kennedy reportedly asked Frank Sinatra to seek election help in West Virginia from Chicago mob leader Sam Giancana. Kennedy also framed the religion issue one of tolerance versus intolerance, and this in particular, helped put Humphrey on the defensive, since Humphrey had long prided himself a champion of tolerance. Kennedy defeated Hubert Humphrey in the West Virginia primary. In addition to Kennedy’s own deft maneuvering in that campaign, he reportedly also had other help.

Kennedy patriarch Joseph P. Kennedy reportedly asked Frank Sinatra to seek election help in West Virginia from Chicago mob leader Sam Giancana. Giancana allegedly helped spread cash around the state and also influenced certain unions to help get out the vote in the primary election. In any case, Kennedy defeated Hubert Humphrey in the West Virginia primary with more than 60 percent of the vote, helping dispel doubts that he could win in Protestant territory and that Americans would support a Roman Catholic nominee. It was Kennedy’s seventh victory in the primaries. On the following day, Humphrey conceded and withdrew from the presidential race. However, there were still other Democratic rivals who could challenge Kennedy at the convention. Chief among these was U.S. Senator Lyndon B. Johnson of Texas.

U.S. Senator Lyndon Johnson would announce his candidacy in July 1960.

U.S. Senator Lyndon Johnson would announce his candidacy in July 1960. Later that summer, in the week before the Democratic National Convention, former U.S. President Harry S. Truman said at a July 2nd, 1960 news conference in Independence, Missouri, that John F. Kennedy lacked the maturity to be President, and that he should decline the nomination. Truman may have been trying to help some of the other Democratic candidates, such as Lyndon Johnson or Adlai Stevenson, who might fare better at a brokered convention. Truman also had tangled with Joseph P. Kennedy in his political past, so there may have been some bad blood there as well. But a few days after Truman made his remarks, Lyndon Johnson on July 5, 1960, announced that he would seek, and said he expected to win, the presidential nomination at the upcoming convention. Johnson asserted Kennedy had less than 600 of the required 701 delegates needed for a nomination. Johnson claimed he had at least 500. Adlai Stevenson, the party’s nominee in 1952 and 1956, had also announced his candidacy about a week before the convention. But Johnson was the bigger threat, and he challenged Kennedy to a TV debate which was apparently held during or leading up to the convention before a joint meeting of the Texas and Massachusetts delegations, and which most observers believed Kennedy won. After that, Johnson was not able to expand his delegate support beyond the South.

Democratic Convention

John F. Kennedy arriving at the Democratic National Convention on July 9, 1960, at the Sports Arena in Los Angeles, California.

John F. Kennedy arriving at the Democratic National Convention on July 9, 1960, at the Sports Arena in Los Angeles, California. As the Democratic National Convention opened in Los Angeles, California at the Sports Arena in July 1960, Frank Sinatra and friends helped fill a “big donors” fundraising dinner on Sunday evening, July 10th at the Beverly Hilton Hotel. Sinatra and Judy Garland performed that evening at the event. More than 2,800 guests attended, with a number of Hollywood attendees recruited by Sinatra, among them: Milton Berle, Tony Curtis, George Jessel, Janet Leigh, Shirley MacLaine, Joe E. Louis, Mort Sahl, and others. Then, as the convention got down to the business at hand, it was formally opened on Monday, July 11th, 1960. On stage, and as part of the opening ceremony, was Frank Sinatra and some of his friends – Sammy Davis, Janet Leigh, and Tony Curtis, and Peter Lawford. Also in attendance were Nat “King” Cole, Shirley MacLaine, Lee Marvin, Edward G. Robinson, Hope Lange, Lloyd Bridges and Vincent Price. Some of these celebrities were introduced to the convention one by one. However, when Sammy Davis, Jr. came forward, he was booed by the Mississippi and Alabama delegations. Davis was devastated. Choked up, he managed to sing through the National Anthem with Sinatra and others, but left the convention hall shortly thereafter.

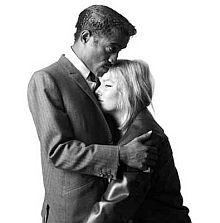

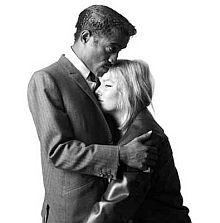

Sammy Davis, Jr. and May Britt, undated. Photo, Brian Duffy.

Sammy Davis, Jr. and May Britt, undated. Photo, Brian Duffy.

Sammy Davis, Jr.

Sammy Davis, as part of Sinatra’s team, had worked hard for Kennedy. On the campaign trail, the Kennedy people would give Davis a list of rallies and cocktail parties in cities and towns where Davis would be playing. Davis would attend these gatherings, sometimes to sing a song or just mingle with the guests. He would later report that he enjoyed doing it and being involved in the excitement of the campaign. Yet politically, inside the Kennedy campaign, Davis was seen as a potential liability in some parts of the country, especially in the south. And Kennedy needed southern Democratic support to win the election. The south at that time was still deeply mired in its segregated ways. In fact, in 1960, most Southern states still had on their books anti-miscegenation laws, which prohibited marriage between whites and blacks. The Supreme Court would not strike down those laws until 1967.

Tony Curtis & Frank Sinatra share a happy moment with Patricia Kennedy Lawford and Peter Lawford at the Democratic Convention, July 1960. Photo: Life/Ed Clark

Tony Curtis & Frank Sinatra share a happy moment with Patricia Kennedy Lawford and Peter Lawford at the Democratic Convention, July 1960. Photo: Life/Ed Clark Frank Sinatra & JFK huddle during a dinner at the Democratic National Convention in Los Angeles, July 1960.

Frank Sinatra & JFK huddle during a dinner at the Democratic National Convention in Los Angeles, July 1960. Two days later in the inner workings of the convention, Kennedy’s team did push through a civil rights plank calling for the end of segregation. Martin Luther King, Jr at the time called it “the most positive, dynamic and meaningful civil rights plank that has ever been adopted by either party.”

However, it would take another four years before some of those provisions would become law.

Patricia Kennedy Lawford, left, looks on as her brother, John F. Kennedy makes his remarks at the Democratic National Convention in Los Angeles, July 1960.

Patricia Kennedy Lawford, left, looks on as her brother, John F. Kennedy makes his remarks at the Democratic National Convention in Los Angeles, July 1960.Working The Floor

Meanwhile, back at the Democratic convention on the evening Davis was booed, Sinatra and other friends helped to work the floor of the convention for Kennedy delegates. He, Judy Garland, Kay Thompson, and others worked to persuade Democratic delegates to support Kennedy for the nomination.

On July 13th, Sinatra joined JFK and the Kennedy clan monitoring the early convention activity by TV from the Beverly Hills mansion of Joe Kennedy’s Hollywood friend, Marion Davis. There were meetings and comings and goings there that day with labor leaders and party bosses from all over the country, preparing for the convention vote. The formal casting of delegate votes for the candidates would occur the following day.

Jackie Kennedy reading about JFK’s nomination in the “Boston Globe” newspaper back home in Hyannis Port, MA, July 14, 1960. AP photo.

Jackie Kennedy reading about JFK’s nomination in the “Boston Globe” newspaper back home in Hyannis Port, MA, July 14, 1960. AP photo. Back at the convention the next day at 9 a.m., Kennedy asked Lyndon Johnson to be his running mate, and to the surprise of many, Johnson accepted. Johnson was not the preferred candidate of many in JFK’s camp, including his brother, Bobby. But Johnson would prove to be an important pick on election night. Meanwhile, after hours, as the political business of that day’s convention activities subsided, Peter and Pat Lawford threw a nomination party for JFK at their Santa Monica home, with Frank Sinatra and various other celebrities attending, among them, Marilyn Monroe.

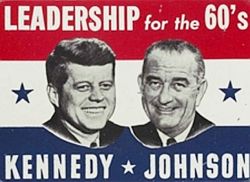

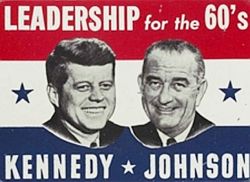

A Jack Kennedy-Lyndon Johnson campaign poster for the 1960 presidential election.

A Jack Kennedy-Lyndon Johnson campaign poster for the 1960 presidential election.

Ocean’s 11

The Rat Pack film, “Ocean's 11,” premiered with a street party in Las Vegas, Nevada, August 1960.

The Rat Pack film, “Ocean's 11,” premiered with a street party in Las Vegas, Nevada, August 1960. A 1960 "Oceans 11" movie poster billing Rat Pack members plus Angie Dickinson.

A 1960 "Oceans 11" movie poster billing Rat Pack members plus Angie Dickinson.

Fall Campaign

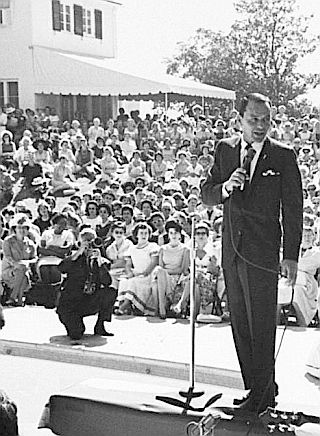

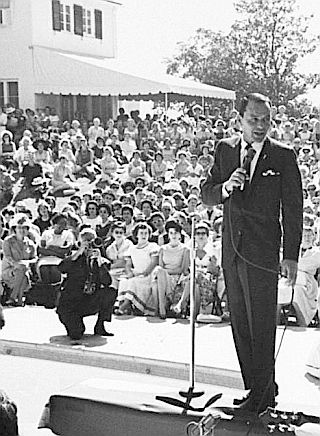

Frank Sinatra appearing at a gathering of Kennedy supporters at the home of Janet Leigh, September 1960.

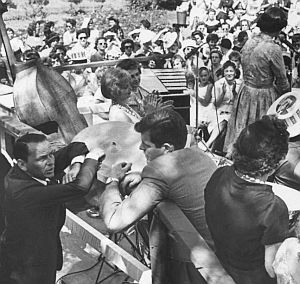

Frank Sinatra appearing at a gathering of Kennedy supporters at the home of Janet Leigh, September 1960. In early September 1960, Janet Leigh and Tony Curtis agreed to use their home for a “Key Women for Kennedy” campaign event. On September 7th, a crowd estimated at 2,000 turned out at Leigh’s place for quite a successful gathering. Ted Kennedy, then the western states coordinator for his brother’s campaign, was also on hand for the event. Frank Sinatra, shown at left, appeared there as well.

Out on the campaign trail, the issue of Kennedy’s Catholic religion had not gone away. Many still feared that government under Kennedy would be unduly influenced by religious interests, and the issue was still seen as a distinct liability for the candidate. As Kennedy made a campaign swing through Texas, he decided to take on the religion issue directly. On September 12, 1960, he spoke before the Greater Houston Ministerial Association in Houston, Texas where he famously told his audience: “I am not the Catholic candidate for President. I am the Democratic Party candidate for President who also happens to be a Catholic. I do not speak for my Church on public matters – and the Church does not speak for me.” Also that September, in Hawaii, which had only recently become a state, Frank Sinatra and Peter Lawford were on location filming The Devil at 4 O’ Clock. While in the state, both did some campaigning for Kennedy, including one performance before an audience of about 9,000 at the Waikiki Shell.

Richard Nixon & JFK debate on television, 1960.

Richard Nixon & JFK debate on television, 1960. Oct 31 1960: JFK tells Temple University students in Philadelphia he’d like to have a 5th TV debate with Nixon, who could “bring President Eisenhower along, too.” Photo: TSutpen.Blogspot.com

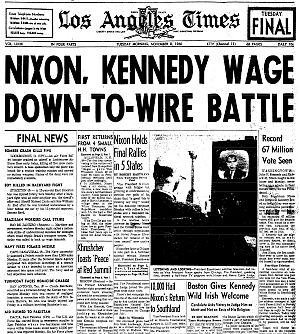

Oct 31 1960: JFK tells Temple University students in Philadelphia he’d like to have a 5th TV debate with Nixon, who could “bring President Eisenhower along, too.” Photo: TSutpen.Blogspot.com Richard Nixon and the Republicans, meanwhile, were pulling out all the stops as well. On Sunday, November 6th, Nixon ran 32-page advertising supplements in Sunday newspapers, and later that evening pre-empted the General Electric Theater on CBS-TV for a 30-minute appeal to voters. On the day before the election, Monday, November 7th, Nixon appeared on ABC-TV for four hours (2-6 pm) in the first telethon in presidential campaign history, assisted by Hollywood celebrities Ginger Rogers, Lloyd Nolan, and Robert Young. Kennedy appeared on ABC-TV that evening too, following Nixon, from 6:00-to-6:30 pm. As election day approached, some polls had Kennedy leading by a slight edge, others had Nixon in the lead. Most believed it was too close to call.

Election Night

Nov. 1960: JFK & aides watching returns on TV after the election. From left: artist Bill Walton, Pierre Salinger, unidentified man on stairs, Ethel Kennedy, Robert Kennedy, Jack Kennedy, RFK. secretary Angie Novello, and campaign aide Bill Haddad. Photo, Jacques Lowe.

Nov. 1960: JFK & aides watching returns on TV after the election. From left: artist Bill Walton, Pierre Salinger, unidentified man on stairs, Ethel Kennedy, Robert Kennedy, Jack Kennedy, RFK. secretary Angie Novello, and campaign aide Bill Haddad. Photo, Jacques Lowe. Frank Sinatra, meanwhile, watched the voting on the West coast from the home of Tony Curtis and Janet Leigh, along with other Hollywood stars and movie people, including Bill Goetze, Billy Wilder, Milton Berle, Dick Shepherd and others. The Curtis-Leigh home that evening served as a “clearinghouse” for Hollywood Democrats all around the country who had worked for Kennedy. Calls that evening were coming in from Henry Fonda in New York, Sammy Cahn in Las Vegas, Peter Lawford in Hyannis Port with the Kennedy family, and also Sammy Davis, Jr., who was then performing at the Huntington Hartford Theater in Hollywood, but giving his audience updates on the election returns.

Peter Lawford & Pierre Salinger following teletype returns, election night, Nov 1960.

Peter Lawford & Pierre Salinger following teletype returns, election night, Nov 1960. On election night, as the early returns came in from large cities in East and Midwest – Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Detroit, and Chicago – Kennedy initially amassed a large lead in the popular and electoral vote. It appeared he had certain victory. However, after some early and premature TV declarations of Kennedy wins in selected states – and some retractions – an hours-long “too-close-to-call” contest set in, stretching late into the night. As later returns came in – especially from the rural and suburban Midwest, the western states, and Pacific Coast states, Nixon began to catch up. Some newspapers, including the New York Times, had even prepared “Kennedy elected” headline copy. But the election was still too close to call. Nixon made an appearance at about 3:00 a.m. that hinted toward concession, but he did not formally concede. It would not be until the afternoon of the following day, Wednesday, November 9th, that Nixon finally conceded and Kennedy claimed victory.

New York Times of November 10th, 1960 announcing JFK victory in presidential election. JFK shown with wife Jackie and family members at Hyannis Port, MA press event.

New York Times of November 10th, 1960 announcing JFK victory in presidential election. JFK shown with wife Jackie and family members at Hyannis Port, MA press event. Back on the west coast the next day, Frank Sinatra went to work at an MGM set in Hollywood where they were making the film, The Devil at 4 O’Clock with Spencer Tracy and others. The film’s director was Mervyn LeRoy, a Republican, with whom Sinatra had made a friendly wager on the election outcome.

A photo reportedly exists of Sinatra riding atop a donkey with LeRoy leading them around the MGM lot, apparently a result of Sinatra winning the wager.

After the election, Rosalind Wyman, who served as the co-chair of the 1960 California Kennedy-Johnson campaign and Democratic National Convention in Los Angeles, singled out Sinatra for his campaign help, saying he went wherever he was needed. Sinatra, of course, was elated with JFK’s victory, and looked forward to a continuing friendship with the president-elect in the years ahead.

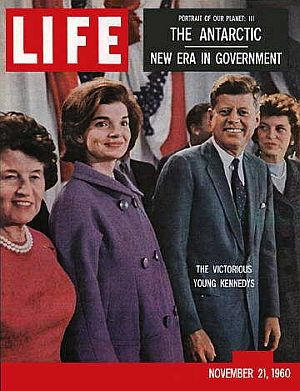

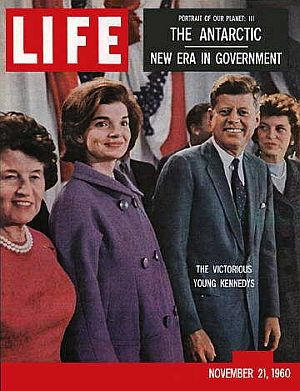

Life magazine features “the victorious young Kennedys” on the cover of its November 21, 1960 edition.

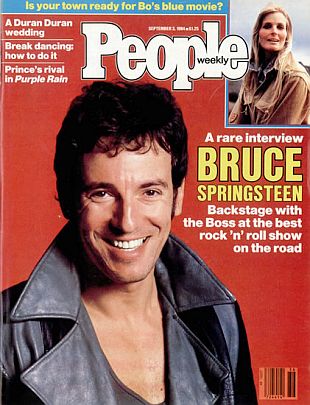

Life magazine features “the victorious young Kennedys” on the cover of its November 21, 1960 edition.See also at this website, for example: “1968 Presidential Race–Democrats” and “1968 Presidential Race – Republicans,” both of which also focus on the Hollywood/politics mixture; “Barack & Bruce, 2008-2012,” covering Bruce Springsteen and other celebrity supporters of Barack Obama’s presidential bids; or visit the “Politics & Culture” category page for other choices. Additional Kennedy family stories can be found at: “Kennedy History: 1954-2013.”

The 1960 campaign is also covered with town-by-town itinerary at, “JFK’s 1960 Campaign.” Stories with Frank Sinatra content include: “The Sinatra Riots, 1942-1944,” “Ava Gardner, 1940s-1950s,” and “Sinatra: Cycles, 1968,” a Sinatra song profile.

Thanks for visiting — and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research and writing at this website. Thank you. —Jack Doyle

____________________________________

Date Posted: 21 August 2011

Last Update: 12 September 2017

Comments to: jdoyle@pophistorydig.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “The Jack Pack, 1958-1960,”

PopHistoryDig.com, August 20, 2011.

____________________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

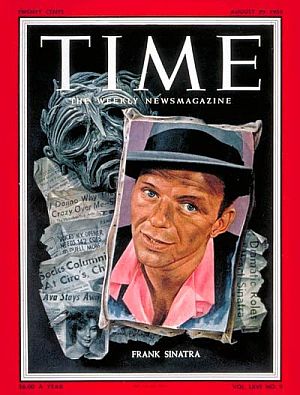

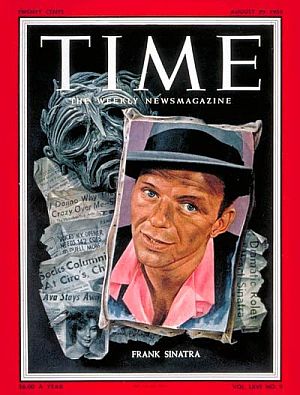

August 29, 1955: Time magazine cover story features Frank Sinatra’s rise to acting fame. Already a famous singer from the mid-1940s, Sinatra in 1954 won an acting Oscar for his role in the film, “From Here To Eternity.” August 29, 1955: Time magazine cover story features Frank Sinatra’s rise to acting fame. Already a famous singer from the mid-1940s, Sinatra in 1954 won an acting Oscar for his role in the film, “From Here To Eternity.” |

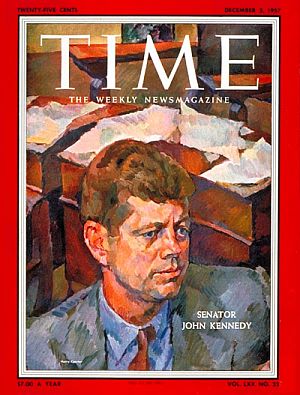

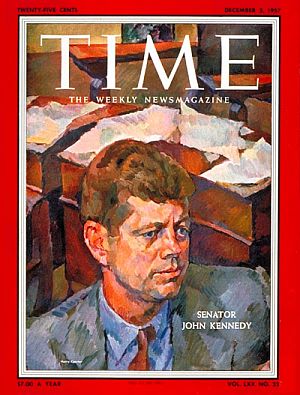

John F. Kennedy, who was first elected to Congress in 1946, is featured on Time’s cover, December 2, 1957, as the “Democrat's Man Out Front.” John F. Kennedy, who was first elected to Congress in 1946, is featured on Time’s cover, December 2, 1957, as the “Democrat's Man Out Front.” |

Frank Sinatra performing at the Desert Inn, 1950s. Frank Sinatra performing at the Desert Inn, 1950s. |

U.S. Senators John F. Kennedy, Hubert H. Humphrey, and Albert Gore Sr. in conversation during the 1956 Democratic Convention. U.S. Senators John F. Kennedy, Hubert H. Humphrey, and Albert Gore Sr. in conversation during the 1956 Democratic Convention. |

Dean Martin, Sammy Davis, Jr., and Frank Sinatra on stage during one of their performances, 1960s. Dean Martin, Sammy Davis, Jr., and Frank Sinatra on stage during one of their performances, 1960s. |

John F. Kennedy and wife Jackie campaigning in Appleton, Wisconsin, March 1960. Photo, Jeff Dean. John F. Kennedy and wife Jackie campaigning in Appleton, Wisconsin, March 1960. Photo, Jeff Dean. |

John F. Kennedy, presidential candidate, meeting with West Virginia coal miners, 1960. John F. Kennedy, presidential candidate, meeting with West Virginia coal miners, 1960. |

John F. Kennedy, campaigning in West Virginia coal country, 1960. John F. Kennedy, campaigning in West Virginia coal country, 1960. |

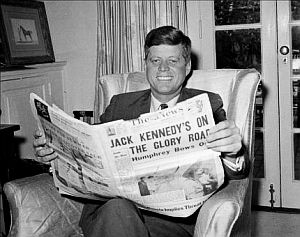

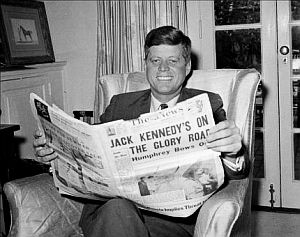

May 1960: John F. Kennedy at home in Washington, D.C. reading newspaper about his victory in the West Virginia primary and rival Hubert Humphrey quitting the race. May 1960: John F. Kennedy at home in Washington, D.C. reading newspaper about his victory in the West Virginia primary and rival Hubert Humphrey quitting the race. |

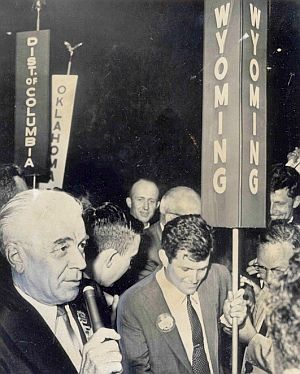

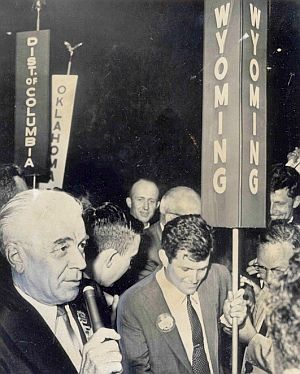

July 1960: Ted Kennedy, center, on the floor of the Democratic National Convention as the Wyoming delegation gives JFK the votes needed for the party's presidential nomination. Photo, L.A. Times. July 1960: Ted Kennedy, center, on the floor of the Democratic National Convention as the Wyoming delegation gives JFK the votes needed for the party's presidential nomination. Photo, L.A. Times. |

Actress Janet Leigh, left, listens to JFK campaign coordinator Edward M. Kennedy, far right, at rally for his brother at Janet Leigh’s home, Sept 1960. Actress Janet Leigh, left, listens to JFK campaign coordinator Edward M. Kennedy, far right, at rally for his brother at Janet Leigh’s home, Sept 1960. |

Frank Sinatra talking with Edward M. Kennedy, lower left at "Key Women for Kennedy” rally at Janet Leigh’s house, Beverly Hills, Sept 1960. Photo: Ralph Crane. Frank Sinatra talking with Edward M. Kennedy, lower left at "Key Women for Kennedy” rally at Janet Leigh’s house, Beverly Hills, Sept 1960. Photo: Ralph Crane. |

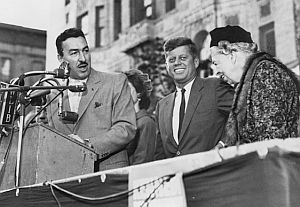

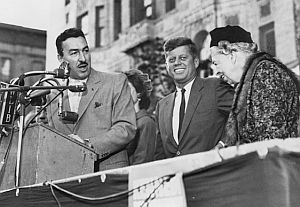

Oct 1960: U.S. Rep. Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. with John F. Kennedy and Eleanor Roosevelt in New York city during Kennedy's presidential campaign. Oct 1960: U.S. Rep. Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. with John F. Kennedy and Eleanor Roosevelt in New York city during Kennedy's presidential campaign. |

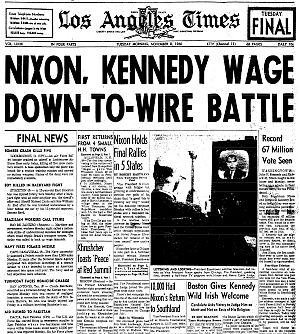

Nov 8, 1960: Los Angeles Times headlines on "down-to-the-wire" presidential election. Nov 8, 1960: Los Angeles Times headlines on "down-to-the-wire" presidential election. |

Ted Kennedy with sisters Eunice and Pat and Ethel Kennedy watching election-night returns at Hyannis Port, MA. AP photo/Henry Griffin. Ted Kennedy with sisters Eunice and Pat and Ethel Kennedy watching election-night returns at Hyannis Port, MA. AP photo/Henry Griffin. |

“Cinema: The Kid from Hoboken,” Time (cover story), Monday, August 29, 1955.

“$15 Dinner to Climax Democrats’ Busy Day; Candidates to Be Endorsed for Two Posts Before Kennedy Speaks at Fete,” Los Angeles Times, February 28, 1958, p. C-10.

JFK Speech, Los Angeles, CA, November 1959, YouTube.com (w/introductory com-ments by Frank Sinatra).

Dorothy Kilgallen, “Sinatra Fails to Show for Kennedy,” Washington Post/Times Herald, December 15, 1959, p. C-7.

“Kennedy Hits Johnson for Avoiding Primaries; Senator in New Mexico Bid for Support Raps Candidates Who Skip Popular Test,” Los Angeles Times, February 8, 1960, p. 1.

John C. Bowes, “The Reign of King Frankie,” Washington Post/Times Herald February 28, 1960, p. AW-8.

“Nixon, Kennedy Score Big Victories in N.H.,” Los Angeles Times, March 9, 1960, p. 1.

“Strategic Warpath in Wisconsin; Kennedy Bandwagon, Challenged By Humphrey, Heads For First Big Test,” Life, March 28, 1960, pp. 22-27.

Robert Ajemian, “Jack’s Campaign Aids: Hard Working Family, Enthusiastic Catholics,” Life, March 28, 1960, pp. 28-29.

Associated Press, “Controversial Writer Is Fired by Sinatra,” Washington Post, Times Herald, April 9, 1960, p. A-3.

“Principals in Near Battle At Benefit Party,” Los Angels Times, May 15, 1960.

“The West Virginia Primary,” The Eleanor Roosevelt Papers, GWU.edu, 2006.

“Sammy Davis Jr. to Wed; Plans to Marry May Britt After Her Divorce in Fall,” New York Times, June 7, 1960.

“Cheers and Boos Greet Kennedy at Rights Rally; Senator Calls for Action Against Racial Discrimination at White House Level,” Los Angeles Times, July 11, 1960, p. 3.

“Delegates Boo Negro; But Sammy Davis Jr. Is Also Applauded at Convention,” New York Times, July 12, 1960.

“Demos Decide Today; Kennedy Out in Front,” Los Angeles Times, July 13, 1960, p. 1.

“Significant Planks in Party Platform,” Los Angeles Times, July 13, 1960.

Kyle Palmer, “Liberals Nail Kennedy To Their Platform,” Los Angles Times, July 13, 1960.

“Sen. Kennedy’s Father Watches in Hideaway,” Los Angeles Times, July 14, 1960, p. 2.

“1960 Democratic National Convention,” Wikipedia.org.

“Kennedy Wants to Cast off Sinatra, London News Says,” Los Angeles Times, July 21, 1960, p. 2.

“Giant Jazz Show to Boost Kennedy,” Washington Post, Times Herald, July 25, 1960, p. 21.

Philip K Scheuer, “Sinatra Premieres ‘Ocean’s Eleven’; Las Vegas Hotels Host Stars; Film Enjoyable…,” Los Angeles Times, August 5, 1960, p. A-7.

“Frankie’s ‘Clan’ Sticking Together,” Washington Post/Times Herald, August 6, 1960, p. D-10.

Bosley Crowther, “The Screen: ‘Ocean’s 11’; Sinatra Heads Flippant Team of Crime,” New York Times, August 11, 1960, p. 19.

Richard Griffith, “‘Ocean’s 11’ Fails to Awe N.Y. Critics,” Los Angeles Times, August 30, 1960, p. A-9.

“Key Women for Kennedy to Be Feted,” Los Angeles Times, September 6, 1960, A-4.

Murray Schumach, “Hollywood Wing in Kennedy Drive; Janet Leigh Opens Home to 2,000 Women as Group Kicks Off Its Campaign,” New York Times, September 8, 1960, p. 40.

“2,000 Open Kennedy Fund Drive,” Los Angeles Times, September 8, 1960, p. A-1.

“Kennedy Confers With Southland Democrats; Candidate Rests at Sister’s Home After Breakfasting With Congress Candidates,” Los Angeles Times, Sept. 11, 1960, p. 1.

“Nixon, Kennedy Meet Face to Face on TV,” Los Angeles Times, September 27, 1960, p.1.

“Kennedy’s Victory Won By Close Margin; He Promises Fight For World Freedom; Eisenhower Offers ‘Orderly Transition’,” New York Times, Nov. 10, 1960, p. 1.

Army Archerd, “1960: Sinatra on Politics” (From the Army Archerd Archive), Variety, November 10, 1960 (with 2008 update).

Gladwin Hill, “Election Pleases the Movie World; Even Hollywood Republicans Are Gratified by Role of TV and Films in Victory,” New York Times, November 11, 1960.

“Sammy Davis Jr. Weds; He and May Britt Married in His Hollywood Home,” New York Times, November 14, 1960.

Paul Schutzer, “Election Night Tension Inside Kennedy House,” Life, November 21, 1960, pp. 36-37.

“Hollywood: Happy as a Clan,” Time, Monday, December 5, 1960.

“Democrats: The Most,” Time, Monday, December 19, 1960.

“Electors Certify Kennedy Victory,” New York Times, December 20, 1960, p.1.

“Campaign of 1960,” John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum.

1960 Election Year Chronology, DavidPietrusza.com.

Theodore White, The Making of the President 1960, New York: Atheneum Publishers, 1961.

Richard Gehman. Sinatra And His Rat Pack: The Irreverent, Unbiased, Uninhibited Book About Frank and “The Clan”, New York: Belmont Books, 1961, 220pp.

Steve Pond, “Frank Sinatra and Politics: His Impact on the Presidency, Then and Now,” Sinatra.com.

Bill Zehme, Mecca With A Dress Code, “The Birth of the Rat Pack,” Sinatra .com.

Earl Wilson. Sinatra: An Unauthorized Biography, New York: MacMillan Co., 1976.

Judith Exner, My Story, New York: Grove Press, 1977.

John Rockwell, Sinatra: An American Classic, New York: Random House, 1984.

Anthony Summers, “JFK, RFK, And Marilyn Monroe: Power, Politics And Paramours?,” The Sun-Sentinel (Fort Lauderdale, Florida), October 27, 1985.

Kitty Kelley, His Way: The Unauthorized Biography of Frank Sinatra, New York: Bantam, 1986.

Patricia Seaton Lawford with Ted Schwarz, The Peter Lawford Story, New York: Carol & Graf, 1988.

Ronald Brownstein, The Power and the Glitter: The Hollywood-Washington Connection., New York: Pantheon, 1990, 437pp.

James Spada, Peter Lawford: The Man Who Kept The Secrets, New York: Bantam, 1991.

Stephen Holden, “Dean Martin, Pop Crooner And Comic Actor, Dies at 78,” New York Times, December 26, 1995.

Nancy Sinatra, Frank Sinatra: An American Legend, Santa Monica: General Publishing Group, and London: Virgin, 1995.

Richard Lacayo, Adam Cohen, Ratu Kamlani, Elizabeth Rudulph, Michael Duffy and Mark Thompson, “Smashing Camelot,” Time, Monday, November 17, 1997.

Pete Hamill, Why Sinatra Matters, Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1998, 185pp.

Stephen Holden, “Frank Sinatra Dies at 82; Matchless Stylist of Pop,” New York Times, May 16, 1998.

Bernard Weinraub, “Requiem for Rats: Ring-a-Ding-Ding, Baby,” New York Times, April 13, 1998.

Shawn Levy, Rat Pack Confidential: Frank, Dean, Sammy, Peter, Joey, and the Last Great Showbiz Party, New York: Broadway Books/Random House, 1998.

Karlyn Barker, “Masterful Singer, Chorus of Praise,” Washington Post, Saturday May 16, 1998, p. A-1.

Max Rudin, “Fly Me to the Moon: Reflections on The Rat Pack,” American Heritage, December 1998.

The Rat Pack, HBO film,1998.

Jeff Leen, “A. K. A. Frank Sinatra,” Washington Post Magazine, Sunday, March 7, 1999, p. M-6.

Lawrence J. Quirk, William Schoell, The Rat Pack: Neon Nights with the Kings of Cool, Harper-Collins, 1999, 368pp.

A&E Documentary Film Series, Vol. 4, “Camelot and Beyond,” The Rat Pack: True Stories of the Original Kings of Cool, 1999.

Alan Schroeder (Northeastern Univ., School of Journalism), Presidential Debates: Forty Years of High-Risk TV, Columbia University Press, 2000.

Peter Carlson, “Another Race To the Finish; 1960’s Election Was Close But Nixon Didn’t Haggle,” Washington Post, Friday, November 17, 2000, p. A-1.

Geoffrey Perrett, Jack: A Life Like No Other, New York: Random House, 2002.

George Jacobs & Willian Stadiem, “Sinatra and The Dark Side of Camelot,” Playboy, June 2003.

J. Hoberman, Film; “A Co-Production Of Sinatra and J.F.K.,” New York Times, September 14, 2003.

Gus Russo, The Outfit: The Role of Chicago’s Underworld in the Shaping of Modern America, New York: Blooms- bury, 2003, 496pp.

Alan Schroeder, “Shall We Dance,” (Northeastern Univ., School of Journalism), Northeastern Univ. Alumni Magazine, September 2004.

Alan Schroeder, Celebrity-in-Chief: How Show Business Took Over the White House, Cambridge, MA: Westview Press, 2004.

Charles Pignone, The Sinatra Treasures: Intimate Photos, Mementos, and Music from the Sinatra Family Collection, Bulfinch, 2004, 192pp.

Max Rudin,”The Rat Pack,” Las Vegas: An Unconventional History, PBS companion book, 2005.

Anthony Summers and Robbyn Swan, Sinatra: The Life, Alfred Knopf: New York, 2005.

Brian Dakss, “Sinatra: The Mob, JFK, Women – Authors Chronicle Roles They Say Each Played In His Life,” The Early Show: CBS News, NewYork, May 17, 2005.

Gary Donaldson, The First Modern Campaign: Kennedy, Nixon, and the Election of 1960, Rowman & Littlefield, 2007, pp. 79–80.

Mary Manning, “Rat Pack Reveled in Vegas; Revered by the World,” LasVegasSun.com, Thursday, May 15, 2008.

Mike Weatherford, “Frank Sinatra: The Swinger and the Strip,” Las Vegas Review-Journal, From Series, “The First 100 Persons Who Shaped Southern Nevada.”

Jon Wiener, “Frank Sinatra: His Way,” The Nation, June 15, 2009.

“The Rat Pack,” Department of Special Collections, University Libraries, Univ. of Nevada at Las Vegas, 2009.

David Robb, “50 Years Ago, Sammy Davis Jr. at Center of Racial Divide,” Reuters .com, Monday, June 28, 2010.

David Ng, “A Photographic History of Frank Sinatra and the Rat Pack,” LATimes.com, October 25, 2010.

Sam Irvin, Kay Thompson: From Funny Face to Eloise, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2010, 416pp.

Tony Nourmand, Shawn Levy, and Graham Marsh, The Rat Pack, Limited Edition, Book of Rat Pack Photos by Sid Avery, Bob Willoughby & others, London: Reel Art Press, 2010, 448 pp.

“Caught on Camera: The Intimate Photos That Show the Rat Pack in Full Swing,” Daily Mail Reporter (U.K,), January 21, 2011.

Benjamin Wideman, “Kennedy’s 1960 Visit ‘Not Something You Ever Forget’,” HTRNews.com, January 25, 2011.

Dean Shalhoup, “High School Kids Benefit from Living History Lesson about JFK,” NashuaTelegraph.com, Saturday, Feb. 26, 2011.

“United States Presidential Election, 1960,” Wikipedia.org.

Rat Pack Photos.

“JFK: Life Before Camelot,” Photo Gallery, Life.com.

Jack Doyle, “JFK’s Profiles in Courage, 1954-2008,” PopHistoryDig.com, Feb. 11, 2008.

Jack Doyle, “JFK, Pitchman?, 2009,” PopHistoryDig.com, August 29, 2009.

WGBH, Boston, “The Kennedys: John F. Kennedy, 35th President,” PBS.org, 1992/1998.

“JFK: The Run for the White House,” Photo Gallery, Life.com.

“JFK: Unpublished, Never-Seen Photos,” Photo Gallery, Life.com.

“The Kennedy Brothers,” Photo Gallery, Life.com.