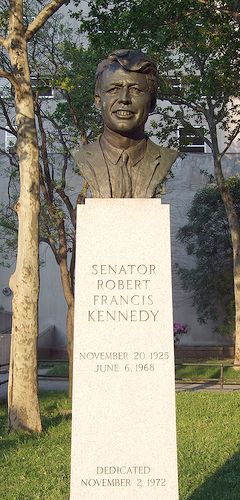

Bust of Robert F. Kennedy, Brooklyn, New York. (Photo, Flikr.com, ElissaSCA, May 2008).

Robert F. Kennedy was born in 1925, the third son of Joseph Kennedy, the patriarch of the powerful Kennedy family of Boston, Massachusetts. His older brother, John F. Kennedy (b.1917 – d.1963), served as the 35th President of the United States.

“Bobby” Kennedy was close to his brother Jack, had directed his political campaigns, and served in his brother’s administration as U.S. Attorney General. The November 1963 assassination of his brother, President John F. Kennedy, had a deep and profound impact on Bobby. He was not quite himself for a considerable time, but gradually recovered.

By September 1964, Robert Kennedy resigned from his post as U. S Attorney General, moved into an apartment at United Nations Plaza in Manhattan, and decided to run for New York’s U.S. Senate seat. Although the Massachusetts born and bred Kennedy was accused of being a “carpetbagger” by running for a seat in New York, he mounted a successful campaign in the 1964 national elections, becoming New York’s junior U.S. Senator. President Lyndon Johnson that fall — the former vice president who had filled President Kennedy’s term following the assassination — had won a landslide victory as president over Republican Barry Goldwater. Kennedy assumed his office as a U.S. Senator in January 1965. National events would later move him to make a run for his party’s 1968 presidential nomination. But what endeared Kennedy to many in Brooklyn was the work he undertook in a community called Bedford-Stuyvesant.

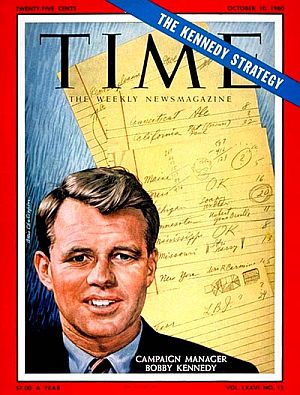

October 10, 1960: RFK lauded on Time cover as manager of JFK's presidential campaign. |

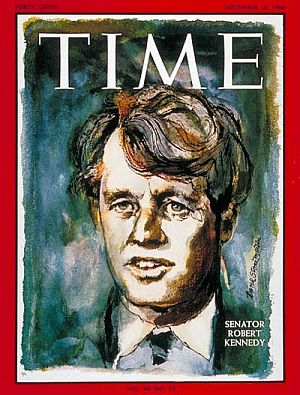

September 16, 1966. RFK on Time cover, now as New York's U.S. Senator. |

America in the mid-1960s was in the thick of the Vietnam War abroad, and grappling with civil rights at home. Robert Kennedy as U.S. Attorney General in the early 1960s, had become directly engaged in civil rights politics, though somewhat awkwardly — approving J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI wiretaps on Martin Luther King on the one hand, yet helping protect King and his family on other occasions, pushing voter rights registration in the south, and dispatching federal marshals to protect Freedom Riders.

President Lyndon Johnson, meanwhile, had embarked on his ambitious Great Society domestic agenda at the outset of his reelection and was instrumental in pushing the 1964 voting Rights Act. But soon, Johnson found that the political and financial demands of the Vietnam War would detract from and undermine his ambitious domestic agenda.

His Politics Change

In the early and mid-1950s, as a young lawyer, Robert Kennedy did a stint as a Senate committee staffer, serving on the U.S. Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations during the reign of Republican Senator Joe McCarthy when the hunt for communists in the Federal government was at its peak. RFK had also worked as an aide to Adlai Stevenson during the 1956 presidential election.

By the late 1950s, Robert Kennedy had made a name for himself as the hard-charging chief counsel of the Senate Labor Rackets Committee and his investigations of labor and organized crime. But after managing JFK’s successful presidential campaign, he had become more fully a national figure. And when he became U.S. Attorney General in 1961, his politics began to change as he dealt with civil rights issues.

Following the assassination of his brother in 1963, and as a U.S. Senator, RFK continued his political metamorphosis. He gradually became a more vocal and aggressive champion for minority rights — for African Americans, Latinos, Native Americans, and immigrant groups.

Kennedy aligned himself with the leaders of civil rights and social justice campaigns, becoming a voice within the Democratic party for a more aggressive agenda on eliminating discrimination on all levels. He supported busing to desegregate schools, integration of all public facilities, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, as well as anti-poverty programs to increase education, provide job opportunities and health care. By the time Robert Kennedy ran for president in 1968, he had become one of the nation’s most prominent spokesmen on behalf of those he called the “disaffected, the impoverished, and the excluded.”

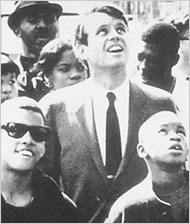

Photo of U.S. Senator Robert F. Kennedy and Donald F. Benjamin of the Central Brooklyn Coordinating Council surrounded by children in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, NY, Feb 5, 1966. Photo Dick DeMarsico.

Bedford-Stuyvesant

During and after World War II, large numbers of African-Americans, migrating from the South, came north to New York and other cities. Some came to Brooklyn and moved into the neighborhood known as Bedford-Stuyvesant. A series of problems there soon led to a long decline in the neighborhood — unemployment, a decline in public facilities and services, inability to deal with increasing crime, and difficulties in municipal government all took their toll on Bedford-Stuyvesant. In the 1960s one of the first urban riots took place in this neighborhood following tensions over charges of racism in local school districts and following police actions. In addition, by 1965, a lawsuit under the Voting Rights Act had been brought charging racial gerrymandering; claiming that Bedford-Stuyvesant was divided among five congressional districts, each represented by a white member of Congress. The suit later resulted in the creation of New York’s 12th Congressional District and by 1968, the election in of Democrat Shirley Chisholm, the first black woman ever elected to the U.S. Congress.

Kennedy in Bed-Sty, 1966.

|

RFK Quotations _________ [ Engraved on the granite surface surrounding the RFK monument at its base are four quotes from Kennedy, which appear, respectively, front, right, left and rear. ] * * * * * * * “Few will have the greatness to bend history itself; but each of us can work to change a small portion of events, and in the total of all those acts will be written the history of this generation.” * * * * * * *

* * * * * * * “All great questions must be raised by great voices, and the greatest voice is the voice of the people speaking out — in prose, or painting or poetry or music; speaking out — in homes and halls, streets and farms, courts and cafes — let that voice speak and the stillness you hear will be the gratitude of mankind.” * * * * * * * “What we require is not the self-indulgence of resignation from the world but the hard effort to work out new ways of fulfilling our personal concern and our personal responsibility.” * * * * * * * “We must get our house in order. We must, because it is right. We must because it is might.” * * * * * * * |

After the tour, Kennedy met with community activists, and they were cynical and irritated. “You’re another white guy that’s out here for the day,” said one. “You’ll be gone and you’ll never be seen again. And that’s that. We’ve had enough of that.” Heading up this delegation was state supreme court judge Thomas R. Jones, the top political leader in the area. And Jones too, was skeptical.

“Weary of Study”

“I am weary of study, Senator,” Judge Jones said to Kennedy. “Weary of speeches; weary of promises that aren’t kept… The Negro people are angry, Senator, and, judge that I am, I’m angry, too. No one is helping us.” Elsie Richardson was a leader of the Central Brooklyn Coordinating Council, the group that brought Kennedy to the neighborhood. Ms. Richardson, too, asked him to go beyond what previous visiting officials had done. And in terms of federal money, the Vietnam War was first in line.

After leaving the meeting with the activists in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Kennedy too, was irritated; upset over the reception he had received; feeling a bit besieged and blamed for something he did not create. But at the same time the problem ate at him, and he wondered if Bedford-Stuyvesant might be the place to try to do something different. Still, his aides were at a loss to see that much of anything could be undertaken there to make a difference. Kennedy started thinking in terms of those he knew in the private sector and at foundations who might help. His idea was to establish something non-partisan and nonpolitical, as far as that was possible.

Business & Foundations

One by one, he was soon enlisting folks to help: McGeorge Bundy at the Ford Foundation; Vincent Astor at the Astor Foundation; the Taconic Foundation who had helped on a black voter registration drive in the south when he was Attorney General. By September 1966, Kennedy and his team were also recruiting business leaders — Thomas J. Watson of IBM; William Paley of CBS; J.M. Kaplan of Welch’s Grape Juice; James Oates of Equitable Life Assurance; George Moore of National City Bank; and Andre Meyer of Lazard Freres. He also recruited an old line New Dealer, David Lilienthal, who had helped with Tennessee Valley Authority, as well as Douglas Dillon and Roswell Gilpatric.

A later recruit was a skeptical Republican businessman, Benno Schmidt, a partner in J. H. Whitney & Co., who had voted for Nixon in 1960 and Kennedy’s U.S. Senate opponent in 1964, Kenneth Keating (“so much the better,” Kennedy would later say, underscoring his effort to make the entity non- partisan). New York’s Republican mayor, John Lindsay — a potential competitor for Kennedy in the future — was also recruited, along with New York’s senior U.S. Senator, Jacob Javits.

Working with Javits in the Senate, Kennedy secured passage of an amendment to the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964 that established the Special Impact Program, allowing for federal funding of community development projects in urban poverty areas. That provision became law in November 1966.

Robert Kennedy at Bed-Sty com- munity meeting, December 1966.

Kennedy Delivers

On December 10, 1966, ten months after he had taken his walk through “Bed-Sty”, Kennedy along with New York Mayor John Lindsay and Senator Javits, presented his plan to the some 1,000 or so people assembled at a Bedford-Stuyvesant school.

The new entity would come to be known as the Bedford-Stuyvesant Development and Service Corporation. There would be two separate corporations: one for the people to decide on the programs and the development, and one comprised of business leaders and mangers who would bring in the investment dollars and help make management decisions.

“The program for the development of Bedford Stuyvesant will combine the best of community action with the best of the private enterprise system,” said Kennedy at the meeting. “Neither by itself is enough, but in their combination lies our hope for the future.”

Robert Kennedy with other officials at announcement of Bedford-Styvesant initiative, December 10, 1966.

Through the 1960s and 1970s, the Bedford-Stuyvesant Restoration Corporation, as it is known today, had its fits and starts, along with the typical battling and in-fighting that comes with any such project. Corporation and community had their ups and downs over the years. Still, 40 years after its creation, the Bedford-Stuyvesant Restoration Corporation is seen as helping the community. Elsie Richardson, one of those who was there with Kennedy in February 1966 told the New York Times in 2009 that the project’s work paid off. “It did a lot for the neighborhood,” she said. “The neighborhood developed a spirit of being able to do things for itself.”

Bed-Sty Today

As of early 2009, the Bedford Stuyvesant Restoration Corporation — located at Restoration Plaza south of Fulton Street — comprises a one-block complex of several buildings, including one that was once an abandoned milk-bottling plant. Colvin Grannum, president of the Bed-Sty Corporation, explained to the New York Times in 2009 that the entity has become a vehicle for “resident-driven revitalization.” Since 1967, the Bed-Sty project has catalyzed important improvements throughout central Brook- lyn. From the beginning, he explained, the Corporation aimed to address neighborhood problems broadly — through the arts, educational programs, employment counseling, job training, tax preparation, etc. Since 1967, the Bed-Sty project has catalyzed important improvements throughout central Brooklyn. It has constructed or renovated 2,200 units of housing; provided $60 million in mortgage financing to nearly 1500 homeowners; attracted more than $375 million in investments; and placed over 20,000 youth and adults in jobs. It also established a Youth Arts Academy offering classes in dance, martial arts, music, visual arts, and theater to approximately 400 students ages 3-19 each year, and its Billie Holiday Theatre offers a 36-week season that serves 30,000 people annually, also providing a training ground for aspiring theater professionals. A primary and continuing goal still remains — what Grannum calls “placemaking,” and having residents value their community and its services. Forty years later, the Bedford-Stuyvesant experience is still a model for other communities across the country.

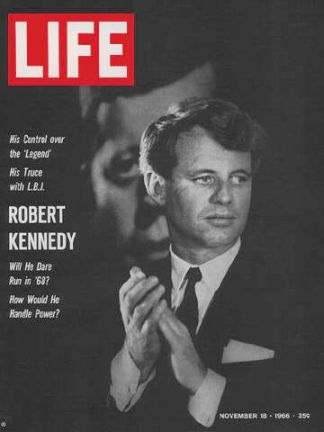

U.S. Senator Robert F. Kennedy on the cover of Life magazine, November 19, 1966, about the time he was engaged in helping establish the Bedford-Stuyvesant initiative. Life asks: ‘Will He Dare Run in ’68?’

For Robert Kennedy, Bedford-Stuyvesant became part of a larger national effort to address the needs of the dispossessed and powerless — the poor, the young, racial minorities and Native Americans. He sought to bring the facts about poverty to the American people, and he visited urban ghettos, Appalachia, the Mississippi Delta, and migrant workers’ camps, sometimes with the national press following.

“There are children in the Mississippi Delta whose bellies are swollen with hunger,” he would tell the press in the 1960s. “…Many of them cannot go to school because they have no clothes or shoes. These conditions are not confined to rural Mississippi. They exist in dark tenements in Washington, D.C., within sight of the Capitol, in Harlem, in South Side Chicago, in Watts. There are children in each of these areas who have never been to school, never seen a doctor or a dentist. There are children who have never heard conversation in their homes, never read or even seen a book.”

Kennedy had also traveled to South Africa in 1966, where he spoke out against the practice of apartheid. A quote from an address he gave there at the University of Cape Town appears on his gravestone at Arlington National Cemetery — “Each time a man stands up for an ideal, or acts to improve the lot of others, or strikes out against injustice, he sends forth a tiny ripple of hope…” By 1968, Kennedy had also called for a halt in further escalation of the Vietnam War. All of these issues became part of his run for the Democratic Presidential nomination in 1968, which ended tragically with his assassination in June of that year.

Kennedy Memorial

Anneta Duveen at work on her Robert F. Kennedy sculpture, 1971.

For more on Robert Kennedy’s run in the 1968 Democratic presidential primary, see at this website, “1968 Presidential Race, Democrats.” See also “Kennedy History,” a topics page with additional stories on JFK and the Kennedy family, and the “Politics & Culture” page for additional stories in that category. Thanks for visiting – and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research and writing at this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

______________________________

Date Posted: 20 July 2009

Last Update: 27 November 2017

Comments to: jdoyle@pophistorydig.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “RFK in Brooklyn, 1966-1972,”

PopHistoryDig.com, July 20, 2009.

_____________________________

Another look at the RFK memorial in Brooklyn, NY.

Arthur M. Schlesinger, Robert Kennedy and His Times, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2002, pp. 786-788.

“The Personal Papers of Thomas M.C. Johnston (1936-2008),” John F. Kennedy Presidential Library & Museum, National Archives and Records Adminis- tration, Boston, MA.

“History – Bedford Stuyvesant Restoration,” Restoration Plaza.org.

“Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn,” Wikipedia.org.

Steven V. Roberts, “Redevelopment Plan Set for Bedford-Stuyvesant; Brooklyn Ghetto Gets Revival Plan,” New York Times, Sunday, December 11, 1966, p.1.

Steven V. Roberts, “Rebuilding Effort Helps Street In Slums to Become Untypical; After a Year, Tangible Signs of Change in Bedford-Stuyvesant Are Few, but Organizers Are Confident,” New York Times, Monday, December 25, 1967, p. 27.

Jake Mooney, “Examining the Kennedy Legacy in Brooklyn,” New York Times, January 30, 2009, p. CY-1.

Jake Mooney, “Star Power, Still Shining 40 Years On,” New York Times, January 29, 2009.

Francis X. Clines, “Bust of Robert Kennedy Unveiled by His Widow,” New York Times, November 3, 1972, Friday, p. 43.