Logo for the 2009 NCAA ‘Final Four’ basketball championship, played in Detroit, Michigan.

The Post story — headlined: “Desperate For a Rebound, Detroit Turns to Basketball” — contrasted the good times for the NCAA with the hard times in Detroit and Michigan, epitomized by the current declining economic fortunes of Detroit’s automakers. NCAA basketball is just one part of what appears to be a rapidly growing “entertainment economy.” But perhaps there is also a broader message to spotlight here: the rise of the “media and entertainment” sectors of America’s economy in recent years versus the declining manufacturing sector.

Manufacturing, obviously, is vital for sustaining any national economy, and Americans would like to see nothing better than a solid manufacturing come-back in the Midwest and elsewhere in the months ahead. Still, in recent decades, the sports, media, and entertainment portions of the American economy have been exploding in value and growth. NCAA basketball is just one part of that — part of what some have called in recent years, “the entertainment economy.” Whether this “new economy” is as desirable as the old industrial variety is another question, certainly, but it is occurring nonetheless.

Sports in general have become a rising and significant part of the U.S. media/entertainment sector. In 1960, for example, there were 42 professional sports franchises, mostly in the northeastern U.S. By 2000,there were more than 110 franchises, and they were spread over more regions of the country. The media, meanwhile, have loomed powerfully over this growth. Since 1980s the annual number of hours of sports programming aired by major broadcast networks and cable systems has more than doubled, rising to 10,000 hours in 2000. The increasing economic value of sports broadcast and cable rights have attracted media and entertainment companies as sports franchise investors, as well as wealthy individuals. And “big event” playoff games and the like, draw lots of attention from would-be host cities.

Ford Field in Detroit played host to more than 72,000 fans for the Final Four NCAA basketball games of early April 2009.

In April 2009, CNN.com reported a story headlined: “Hawaii Looks to Sports for Economic Boost,” explaining how the NFL Pro Bowl game — featuring all-star professional football players in an end-of-season contest — has been an important contributor to the state’s economy for more than 20 years. The game had been played in Honolulu at Aloha Stadium every year since 1980, and it sold out every time. Honolulu Mayor Mufi Hannemann explained that the tens of thousands of people who came to that game every year spent “at least $30 million” across the state. Honolulu lost the game to Florida recently, but Mayor Hannemann is optimistic about getting it back in 2011 and 2012. Hannemann also co-chairs the U.S. Conference of Mayors’ Olympic Task Force, which is hoping to bring the Olympics to Chicago in 2016. Hawaii could benefit from that as well, becoming a stopping off point for visiting fans and participating teams on their way to Chicago. Sports, it seems, is an important part of Hawaii’s economic planning.

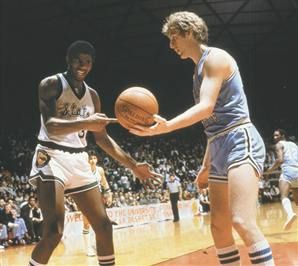

1979 NCAA championship players Magic Johnson of Michigan State, left, and Larry Bird of Indiana, right.

NCAA basketball, a part of the larger sports universe, has become its own big business. But this has happened in a relatively short space of time, with broadcast and cable television serving as a powerful handmaidens. NBC telecast the championship NCAA game over its network for the first time in 1969, continuing to do so through the 1970s. There was no cable television then.

By 1979, however, there came Bill Rasmussen, founder of ESPN, an “all sports” cable TV network. Rasmussen had rounded up broadcasting rights for tape-delayed NCAA basketball games as part of what he was then building. There was little TV coverage then of the games leading up to the NCAA finals. It also happened about that time that fan interest in college basketball was ignited by two young rival players named Magic Johnson and Larry Bird who battled each other in the NCAA finals.

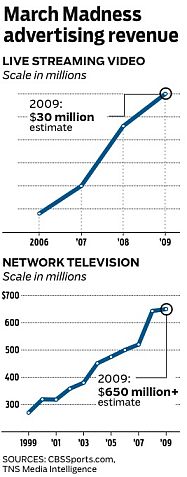

CBS' ad revenues.

In 1979, the NCAA tournament had a 40-team field. It was expanded twice over the next six years, to 48 teams in 1980 and 64 teams in 1985. The TV rights fees were $5.2 million in 1979. They doubled in 1980. By 1982, when CBS outbid NBC for the tournament, the price went to $48 million. In 1985, they doubled again to $96 million. By 1994 CBS paid $1.73 billion for NCAA games through the year 2002. The current package through the year 2011 cost CBS $6.2 billion. But CBS appears to be getting some of that back in ad revenues, both from conventional broadcast and the internet (see graphic).

The televised play of the Final Four NCAA basketball tournament, of course, is only part of the NCAA tournament’s overall economic effect. And basketball is only one of many NCAA sports with championship events, with various college conferences and leagues participating as well. Advertisers from Nike to Chevrolet have been attaching themselves to NCAA sports, and in some cases, individual players, for some time now. On March 10, 2009, for example, Nike announced it would outfit the players of five NCAA teams for tournament play — Duke, Gonzaga, Memphis, Michigan State, and the University of Oregon. Nike would equip the players head-to-toe with a ‘360’ treatment, providing “base-layer apparel, unique uniforms, and customized footwear”. Pontiac, Coca-Cola, AT&T meanwhile, were among prominent Final Four advertisers.

One of a myriad of NCAA video games available for a number of college sports.

The Bigger Picture

College sports, of course, are only a sliver of the great American sports pie, and the U.S., only one part of the larger global sports scene. But adding up only the “sports parts” of the media/ entertainment/advertiser juggernaut that is now found globally — Media & entertainment now contribute well north of $500 billion annually to the global economy, and some analysts expect that an even more powerful sports/entertainment component will emerge in the decades ahead. whether World Cup Soccer, Indian cricket, Olympic events, tournament golf and tennis, NASCAR racing and more — plus the prospect of NFL, NBA and Major League Baseball expansion abroad in the future, and one can get an idea of the shift that is occurring in national and global economies. And sports, of course, are only one part of the bigger media/ entertainment engine. There is Hollywood and Bollywood, the music industry, television and radio, Broadway and the West End, the internet, video games, hand-held entertainment, related software/ hardware, and much more. These are all economic powers within the media/entertainment equation. They now contribute well north of $500 billion annually to the global economy, and some analysts expect that an even more powerful sports/media/entertainment component will emerge in the decades ahead, current economic difficulties notwithstanding. NCAA basketball, and its elevation in recent decades to mega-sport event status, illustrates how modern societies are incorporating media, sports, and entertainment elements as increasingly important economic contributors.

Stay tuned to this website for future stories on these and related topics. Other stories at this site on entertainment economics and its history include: “Disney Dollars, 1930s” and “All Sports, All the Time, 1978-2008,” about the rise of ESPN. For additional sports stories see the “Annals of Sport” category page. Thanks for visiting — and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research and writing at this website. Thank you. — Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

____________________________

Date Posted: 5 April 2009

Last Update: 22 March 2019

Comments to: jdoyle@pophistorydig.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Basketball Dollars, NCAA History,”

PopHistoryDig.com, April 5, 2009.

_____________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

Liz Clarke, “Desperate for a Rebound, Detroit Turns to Basketball; Local Officials, NCAA Organizers Hope Final Four Provides Lasting Boost to Struggling City, Washington Post, Thursday, April 2, 2009, p. A-1.

Harold L. Vogel, Entertainment Industry Economics: A Guide for Financial Analysis, Boston: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

Michael Wilbon, “30 Years Ago, Madness Tipped Off,” Washington Post, Thursday, March 26, 2009, p. E-1.

Robert A Baade and Victor A Matheson, “An Economic Slam Dunk or March Madness? Assessing the Economic Impact of the NCAA Basetball Tournament,” in John Fizel and Rodney D. Fort, Eds, Economics of College Sports, Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers, 2004, pp. 111-134.

John Fizel and Rodney D. Fort, Eds, Economics of College Sports, Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers, 2004.

Business Wire, “Nike Outfits NCAA Basketball Teams for Battle with Innovative Uniform System,” March 10, 2009.

“NCAA Men’s Division I Basketball Championship,” Wikipedia.org.

“2009 NCAA Men’s Division I Basketball Tournament,” Wikipedia.org.

Steve Wieberg & Steve Berkowitz, “NCAA, Colleges Pushing the Envelope With Sports Marketing,” USA Today, April 1, 2009.

Eric Benderoff, “NCAA Tournament: CBS Winning in The Online-Revenue Bracket,” Chicago Tribune. com, March 19, 2009

“NCAA, Member Schools Continue To Work More Like A Business,”SportsBusinessDaily.com, April 2, 2009.

Bloomberg, “CBS Says Internet Ad Revenue for NCAA Tournament May Rise 30%,” March 10, 2009.

Seth Davis, When March Went Mad: The Game That Transformed Basketball, St. Martin’s Press, 2009.