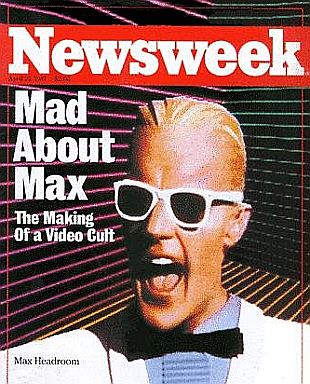

April 1987 Newsweek cover. "I'm an image whose time has come,” says Max Headroom.

The British-derived show was quite popular in its limited 1987-1988 American run on ABC-TV, but was pulled off the air before its final two episodes aired. Still today, the show has something of a cult and on-line following and remains one of television history’s more engaging self-critiques.

Max Headroom was a show about an acci- dentally-created, computer-generated being named “Max Headroom” who lived inside a television network’s computer system. Max, as he was known, was forever randomly popping up in each of the televised episodes with pearls of wit and wisdom, delivered in his trademark computer-to-blame stutter, often aggravating friends and foes alike. Still, Max was a generally likeable creation once viewers got to know him.

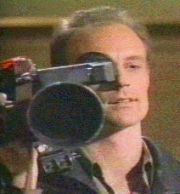

Max Headroom the character was “born” when an actual news reporter named Edison Carter — ace investigative, mini-cam-toting reporter for Network 23 — had a near-death encounter in pursuit of a story. On a motorcycle, Carter was racing into a parking garage on the trail of some hot information when he smashed through, and was knocked out by, an automated entrance gate emblazoned with the warning phrase “maximum headroom.” That was the last phrase the erstwhile reporter recorded in his brain.

Ace reporter, Edison Carter, inadvertently becomes the basis for the computer-generated 'Max'.

In the process of Carter’s brain being scanned into the computer, a digital being is created — i.e., “Max” — who in appear- ance and manner resembles the real-world Edison Carter. The new entity is officially dubbed “Max Headroom” after he stutters through that phrase in his first on-screen appearance. Max, of course, lives in the computer.

Ace reporter Edison Carter, meanwhile, fully recovers from his trauma and returns to video reporting. Max, however, begins to evolve on his own as a mostly uncontrolled character and independent agent wandering around inside his the television network’s computer world. With that, more or less, the Max Headroom TV series was introduced to the American audience. The first episode aired on the ABC network in March 1987.

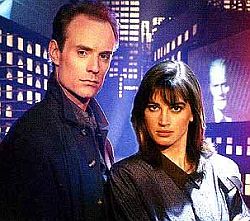

Edison Carter & Theora Jones at Network 23 with Max Headroom in the background.

Back in the studio — though plugged into Carter’s ear while he is in the field — is his good-looking controller, Theora Jones, played by Amanda Pays. These two are sort of a item, and they continue their romantic tension throughout the series.

Other characters include teenage computer whiz and hacker, Bryce Lynch, played Chris Young, who is also Network 23‘s one-man technology research department. Bryce often deals with Max as he pops up in the computer network and is also involved in some of the network’s nefarious doings (he scanned Carter’s brain into the computer, for example, and helps design other computer-TV manipulations). Bryce, however, has sympathies for Edison, Max, and Theora.

Edison Carter, Theora Jones, Murray, Ben Cheviot, and boy-wonder Bryce at top.

Ned Grossberg, not shown, is the former head of Network 23, forced out after Edison Carter’s near death, and then becoming head of rival Network 66. Grossberg is played by Charles Rocket.

A character called Blank Reg is one of the “blanks” — those without computer identities. He is played by W. Morgan Sheppard. Blank Reg is the renegade cyberpunk owner of the outlawed and underground BIG Time TV station. At times, Blank Reg is also a friend to Edison Carter.

Dark, Grimy World

The "Max Headroom" series depicted a dystopia where TV sets were strewn about everywhere, even in the city's slums.

Films such as The Road Warrior (1981) and Bladerunner (1982) are also believed to have influenced the look and tone of the world of Max Headroom and the show’s setting. The world in which Edison Carter does his reporting is a tough, grimy-streets type of world where life is not always valued. Youth punker gangs inhabit this world. As do “blanks,” citizens that have managed to avoid being recorded in the corporate databanks of the day, and live outside the system as subversive have-nots. There is also a mafia-organized sport called “raking,” a deadly form of motorized skateboarding.

Newtork 23 corporate executives shown at board meeting where they can also monitor "intant tele-ratings."

The "Network 23" building headquarters in "Max Headroom" TV series.

More city slums with ubiquitous TVs.

In one episode called “Dieties,” an old flame of Edison’s is running a TV ministry that promises to resurrect people after they die by restoring their personalities from copied profiles stored in a computer. The old flame tried to use Edison to retrieve the computer-generated version of Max, as her church wanted to learn Max’s secrets so it could offer the technique to preserve its members’ personalities eternally — just like Max.

British Invention

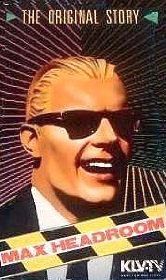

Cover of VHS for original U.K. "Max Headroom" film.

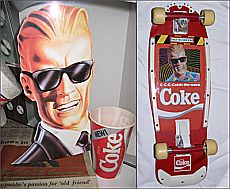

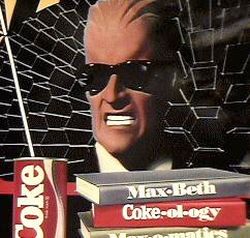

Some of the Max Headroom “New Coke” promo items for short-lived ad campaign.

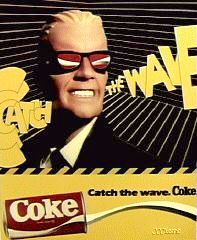

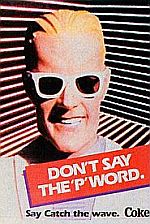

Meanwhile, the U.K.’s Max Headroom TV video show continued running for a few more seasons. There were also a few related TV specials. The Max Headroom video show format then migrated to the U.S. in a somewhat different form, where Max, for a time, became a late night talk show host. From there, Max became more widely known in the U.S., especially after he picked up a commercial advertising gig with Coca-Cola, becoming the “spokeshead” for Coca-Cola’s “New Coke” advertising campaign. These ads used the slogan “Catch the Wave” — or in Max stutter- speak, “Ca-Ca-Catch the Wave.”

Max Headroom for Coke. "Catch the Wave."

Max Headroom Coke ad.

Despite Max’s best promotional efforts, the product was a flop. Some reports have Max continuing to appear in Coke ads through 1987-88.

The consumer outcry against New Coke, however, was loud and immediate. Less than three months after its introduction, in mid-July 1985, Coke announced that the old version, which never went off the market, would return as “Coke Classic.” New Coke, meanwhile, wasn’t immediately halted. It was renamed Coke II in 1990, and continued to be manufactured in the U.S. for another decade or so until it was dropped sometime after 2002. Reportedly, it continued to be sold abroad for a time thereafter.

Cinemax, Talk Show

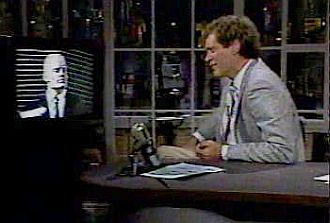

Max, meanwhile, went on to further TV fame and popular notice. By the mid-1980s, there were a variety of Max Headroom stories appearing in the media, including those on Entertainment Tonight, CNN Headline News, and NBC News. Max did a two-part interview — via television screen, of course — on the David Letterman Show July 17, 1986. That interview can be found on You Tube and other online video sources. In August 1987, the Cinemax pay-TV cable channel in the U.S. aired the earlier U.K. Max Headroom video series under the title, The Original Max Talking Headroom Show, which included six episodes of his talk show interviews and music.

In 1987, the original U.K.-made Max Headroom TV film was also released on home video. That video package included a sweepstakes promotion (above) featuring Max explaining the rules of the game at the beginning and end of the film. Portions of that video are offered above to give readers unfamiliar with Max Headroom a sampling of his style and mannerisms as he appeared on screen in his various TV roles — of course, woven into the plots of those shows around various story lines. The video above includes only the “sweepstakes” portion of the tape, with Max, in this instance, explaining the game’s rules. Again, this video is only offered here for those who have not seen the TV show, or know little of the character, as the clip does provide a look at his mannerisms and on-screen humor.

Max Headroom, TV star!

In the U.S., the Max Headroom TV series began as a mid-season replacement in the spring of 1987, and was renewed for the fall season. The spring season ran from March to May 1987 on Tuesday evenings in the 10-11 p.m. time slot. The fall season ran August-October 1987 on Friday evenings in the 9-10 p.m. slot. The show initially developed a loyal following of fans, but it wasn’t everyone’s cup of tea. With its cyberpunk characters and its “set-in-the-future” storyline, Middle America didn’t always get it, and at least part of that market was needed for success. Viewer ratings could not be sustained. Max also had some stiff competition, as the show ran in the same time slot as CBS’s Top 20 hit, Dallas, and NBC’s Top 30 hit, Miami Vice.

|

“Max Headroom” _____________________ Blipverts |

As as result, Max Headroom was cancelled part-way into its first broadcast season, with leftover episodes aired in the spring of 1988. But some felt the show’s biting satire — aimed at TV itself, and TV management in particular — was part of the reason for its abrupt demise. In some quarters it was felt that ABC “suits” were among those being lampooned. So, after only 14 episodes, two of which were never aired, Max was cancelled. But the show did leave an impression.

“Critics admired the series’ self-reflexivity, its willingness to pose questions about television networks and their often unethical and cynical exploitation of the ratings game,” observed Henry Jenkins in one synopsis of the show for the Museum of Broadcast Communications. Max Headrooom also parodied game shows, political advertising, tele-evangelism, news coverage, and TV commercials. At it’s peak, the Max Headroom show was seen on cable TV in 20 countries. In England, meanwhile, Max had two best-selling books, one of which was titled Max Headroom’s Guide to Life. There was also a range of Max Headroom merchandise, including T-shirts, which at the time and in some locations reportedly outsold Madonna T-shirts. As Newsweek put in April 1987: Max Headroom had become “the world’s first computer-simulated megastar.”

The Max Message

"Max Headroom" being interviewed by David Letterman, believed to be July 1986.

Cover of the August 2010 DVD, "Max Headroom: The Complete Series."

Max Headroom, in any case, didn’t die after its 1987-88 short-circuited run at the prime-time American market. As personality and show, Max Headroom went on to live another day in cable. In 1994-95, the series was re-shown on the Bravo cable TV channel. In 1995-96, the U.S. series also ran on SyFy cable channel; in 2002, it appeared on Tech-TV. And today, the series lives on in various forms at any number of websites, some of which are listed below in “Sources.”

"Maximum headroom" warning.

See also at this website the “TV & Culture” directory page, which includes additional stories on the history of television, TV advertising, TV and politics, and more. Other story choices at this website are available at the Home Page or from the Archive. Thanks for visiting — and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research and writing at this website. Thank you. — Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

_____________________

Date Posted: 16 November 2010

Last Update: 16 February 2019

Comments to: jdoyle@pophistorydig.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Max Headroom, 1984-1988,”

PopHistoryDig.com, November 16, 2010.

_____________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

Some Max Headroom Coca-Cola ad imagery. |

Network 23's Edison Carter in the field. |

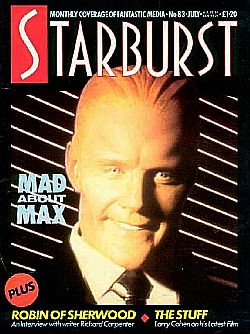

Max Headroom also appeared on the July 1985 cover of Starburst magazine. |

Max is simply amazed by all this info! |

Henry Jenkins, “Max Headroom,” Museum of Broadcast Communications, Museum.tv.

Max Headroom, a film by Steve Roberts, From an original idea by George Stone, Rocky Morton and Annabel Jankel. Directed by Rocky Morton and Annabel Jankel, produced by Peter Wagg; Executive Producer Terry Ellis, Chrysalis Visual Programming Ltd., for Channel 4. This movie ran in the U.K. on Channel 4 — April, 4th 1985 @ 9.30-10.35 pm. The film was used to introduced Max Headroom, Edison Carter, Theora Jones, Murray, Bryce Lynch and Blank Reg. The U.K. television film was later rewritten and cut down to become the American TV series season opener, “Blipverts.”

John J. O’Connor, “TV Review; ‘Max Headroom Show’,” New York Times, October 30, 1985.

Kurt Loder, “Max Mania: A ‘Computer Generated’ Talk-Show Host, Max Headroom Has Become TV’s Latest Overnight Sensation.” Rolling Stone, August 28, 1986.

John J. O’Connor, “Cable’s Max Headroom, a True Media Creation,” New York Times, October 2, 1986.

Jube Shiver, Jr., “C-C-C-Catch The Wave. Max Headroom New TV Marketing Star Finds Success Is Going to His Head,” Los Angeles Times, November 17, 1986, Business, p. 1.

John J. O’Connor, ” ‘Max Headroom’ Series Premieres on ABC,” New York Times, Tuesday, March 31, 1987, p. C-18.

Harry F. Waters, Janet Huck & Vern E. Smith, “Mad About Max: The Making of a Video Cult,” Newsweek, Cover Story, April 20, 1987.

Terry Atkinson, “The Mixed-up World of Max Headroom Creators,” Los Angeles Times, May 5, 1987, Calendar/Entertainment, p. 1.

John J. O’Connor, TV Reviews, “Max Headroom as Host Of an Interview Show,” New York Times, August 6, 1987.

Terry Atkinson, “The Mixed-up World of Max Headroom Creators,” Los Angeles Times, May 5, 1987, Calendar/Entertainment, p. 1.

Diane Haithman, “N-N-N-NO M-M-MORE ‘M-M-MAX’,” Los Angeles Times, October 15, 1987, p. C-1.

Joe Struss, “Max Headroom Episode Guide,” Iowa State.edu.

“20 Questions for Max Headroom,”Playboy, Holiday Anniversary Issue, January 1987.

“Max Headroom”(TV series), Wikipedia.org.

“Max Headroom”(character), Wikipedia.org.

Bill Thompson stories at, Weird Science-Fantasy Web Pages.

MmaxHeadroom webpage (some product sum- maries & episode description)

“Max Headroom Mega Post — TV/DVD Rips,” Rapid.org, October 31, 2009.

“Max on YouTube,” The Max Headroom Chron- icles.

“The Karl Lorimar Max Headroom Sweepstakes,” YouTube.com.

________________________________________