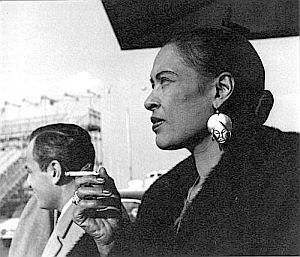

Billie Holiday, jazz singer, circa 1930s.

Billie Holiday by 1939 was a known singer in the New York jazz scene who had done brief stints as a big band vocalist with Count Basie in 1937 and Artie Shaw in 1938.

With Shaw’s band, she became one of the first black women to work with a white orchestra. She also had a number of popular songs by then, dating to 1933 and one of her first recordings, “Riffin the Scotch,” which she recorded with Benny Goodman.

In fact, between 1934 and 1939, Billie Holiday had more than 30 singles that were later considered to be in the Top 20 of that era. Yet, despite her output and popular songs, she was not then a mainstream star; not a household word. But “Strange Fruit” was about to change that. However, the song was clearly a departure from her earlier work, as it had a very discomforting message. Still, “Strange Fruit” was the song that became something of dividing line in Holiday’s career, making her popular, and some say, changing her style as well. More on Holiday and her career in a moment. First, some background on the song.

Poem-to-Song

“Strange Fruit” was first written as a poem by a Jewish high-school teacher from the Bronx, New York named Abel Meeropol, who also used the name Lewis Allan. Meeropol wrote his poem — about the 1930 lynching of two black men in Marion, Indiana – after seeing Lawrence Beitler’s photograph of the lynching. He first published his poem in the January 1937 edition of The New York Teacher, a union magazine. He later set the poem “Strange Fruit” to music and his song gained some success as a protest song in the New York area, performed at one point by black vocalist Laura Duncan at Madison Square Garden.

August 7, 1930 photo of Thomas Shipp & Abram Smith, lynched in Marion, Indiana, for allegedly murdering a white factory worker and raping his female companion.

Barney Josephson had either heard of “Strange Fruit” from friends, or was given a copy by Meeropol himself. In any case, he was quite taken with the song’s imagery and gave it to Billie Holiday, who was then performing at his club, hired at the suggestion of John Hammond.

Holiday at first, was somewhat troubled by the song and put off by its theme, and told Josephson she wasn’t sure she wanted to sing it and would think it over. But she soon agreed to perform the song at Café Society; the main room there held about 220 people. She performed the song for the first time in January 1939. She continued using the song in her nightclub routine, although she was somewhat fearful of retaliation given the song’s charged content in those times.

Josephson, meanwhile, recognized the impact of the song and insisted that Holiday close all her shows with it. In her performance, just as the song was about to begin, waiters would stop serving, the club lights would go down, and a single spotlight would focus on Holiday as she began. During the musical introduction, Holiday would stand with her eyes closed – and as some saw it, as if she were evoking a prayer. With the final note of the song, all lights in the club would go dark, and when they came back on, Holiday would be gone from the stage. According to reports from band members, after performing the song Holiday would sometimes break down emotionally. “Strange Fruit,” in any case, became a regular part of Billie Holiday’s live performances, and the song’s reputation, at least initially, grew from her nightclub act. However, making a vinyl recording of the song for a larger public audience was another matter.

|

“Strange Fruit” Southern trees bear a strange fruit Pastoral scene of the gallant South Here is the fruit for the crows to pluck |

Music Player

“Strange Fruit” – Billie Holiday

Holiday had approached her own record label, Columbia, about recording the song. Columbia refused, fearing a backlash from Southern record retailers and negative reaction from affiliates in Columbia’s co-owned CBS radio network.

She then turned to a friend, Milt Gabler, as Gabler’s record label, Commodore, produced alternative jazz. Gabler worked out an arrangement in 1939 with another label, Vocalion Records, to record and distribute “Strange Fruit.”

Holiday recorded the song in Commodore’s studios at two sessions – one in April 1939 and again later, in 1944. She would also record it at a later date for the Verve record label. “Strange Fruit” became controversial, and over the years, Holiday’s biggest selling record. But not at first. In fact, the song was banned on many radio stations. (And beyond that, federal drug agents would come after her and order her to quit singing “Strange Fruit.” More on this at “Targeting Billie” sidebar later below.)

Although the Commodore release of “Strange Fruit” did not get extensive radio play, the record sold well, which Gabler attributed in part to the record’s other song on the flip side, “Fine and Mellow,” which was a jukebox hit. But “Strange Fruit” also rose on the charts, according to one source, peaking at No. 16 on July 22, 1939. The song also helped put Billie Holiday in the national spotlight. “‘Strange Fruit’ was to Billie what ‘Of Human Bondage’ was to Bette Davis or ‘The Petrified Forest’ to Humphrey Bogart,” wrote Michael Brooks in 1991 liner notes to a Billie Holiday collection. “It brought her national recognition, fame and a very modest fortune. It also attracted celebrity hunters of the worst sort, plus the type of men who were interested in nothing but a free ride…” But some critics, Brooks among them, also believed that “Strange Fruit” changed Holiday’s style, and led her to take on other concerns of the oppressed with her music. “She began to live the part and see herself as the living symbol of injustice and oppression,” wrote Brooks. This change in Holiday’ style, lamented by some, was a gradual process in which she began to interpret her songs rather than just naturally sing them. Yet for many fans and critics, it was her musical interpretation and her singular vocal style in marking those interpretations, that made Holiday’s work so distinctive and impressionable.

Billie Holiday’s “Strange Fruit,” here on the Commodore label, recorded April 1939. Click for digital.

David Margolick, who published a book about Holiday and the song in April 2000, explains that “Strange Fruit” has defied easy musical categorization over the years, and consequently, has not received thoughtful study by social historians and other analysts. “It’s too artsy to be folk music, too explicitly political and polemical to be jazz,” he explains. But his book – Strange Fruit: Billie Holiday, Cafe Society, And An Early Cry For Civil Rights – provides an in-depth look at the song, its artist, and the times. “Surely,” he says, “no song in American history has ever been guaranteed to silence an audience or to generate such discomfort.” In 2002, the Library of Congress added the song to the National Recording Registry. “Strange Fruit” is also included on the “Songs of the Century” list, an education project of the Recording Industry Association of America, the National Endowment for the Arts, and Scholastic, Inc. — a project that aims to “promote a better understanding of America’s musical and cultural heritage” in American schools.

Billie Holiday shown on an image used for an album collection of her greatest hits. Click for album CD.

Billie Holiday

Nicknamed “Lady Day” by her friend and musical partner, saxophonist Lester Young, Billie Holiday became an influential force in jazz and popular music from the mid-1930s through the 1950s. She had a novel way of phrasing and manipulating a song’s lyrics when she performed – a unique vocal style and tempo that was inspired by the jazz music itself. Holiday became known for that style, and was admired worldwide for her deeply personal, intimate approach to her music. Critic John Bush wrote that she “changed the art of American pop vocals forever.”

Holiday co-wrote a share of her songs, and several of them became jazz standards, such as “God Bless the Child”, “Don’t Explain,” “Fine and Mellow,” and “Lady Sings the Blues.” She also became famous for singing jazz standards including “Easy Living,” “Summertime,” and “Good Morning Heartache.”

Billie Holiday was born in April 1915, and her birthplace was believed to be Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, although there is some uncertainty about her records. She was then named either Eleanora Fagan or Elinore Harris, according to differing sources. Her early childhood, in any case, was difficult and unsettled, as she was cared for by a succession of relatives and others, mostly in Baltimore, Maryland. In 1925, at about age nine, truancy from school landed her in a reform school for troubled African American girls. Some reports say she was raped at age 10 by a neighbor. By age 14 she was living in a brothel with her mother who had turned to prostitution in order to survive. Billie too, was used for prostitution. Arrested with her mother when the brothel was raided, only more hard times appeared to be in Billie’s future.Through her travail, however, music had offered her some refuge, as she had listened to the music of Bessie Smith and Louis Armstrong. In 1929, with an urge to try it for herself, she teamed up with a neighbor, tenor sax player named Kenneth Hollan, and began performing at clubs in New York city. In 1931, she began using the name “Billie Holiday,” taken from a combination of the name her favorite actress, Billie Dove, and her father, Clarence Holiday, who had played with Fletcher Henderson’s band as a guitarist. By the end of 1932, at the age of 17, she began working at a club called Covan’s (also known by some as Monette’s) on West 132nd Street, where she was heard by Benny Goodman, John Hammond, and others. The first official recognition of her talents seems to have come from Hammond who heard her at Covan’s and wrote in the April 1933 issue of Melody Maker that she was “a real find,” calling her “incredibly beautiful and sings as well as anybody I ever heard.” Billie Holiday made her recording debut with Benny Goodman in late 1933, producing two songs: “Your Mother’s Son-In-Law” and “Riffin’ the Scotch.” The latter reached No. 6 on the pop charts in late 1933 and early 1934.

Billie Holiday in a Wm. T. Gottlieb photo with her famous and beloved dog, “Mister,” New York, Feb 1947. Click for photos.

In 1935 she appeared in Duke Ellington’s film short Symphony in Black, which featured his extended piece ‘A Rhapsody of Negro Life’. It won an Academy Award as the best musical short subject and also helped introduced Holiday to a broader audience, as she played a woman being abused by her lover and sang “The Saddest Tale.” In 1933-34, Holiday was signed to Brunswick Records by John Hammond to record current pop tunes with Teddy Wilson, converting them to the new “swing” style for the growing jukebox trade. It was 1937 when she joined Count Basie’s band, then on tour. This was also when Lester Young – who played tenor saxophone and became one of Holiday’s closest friends – gave her the nickname “Lady Day.” In return, she called him “Prez,” which meant he was pretty special in her book, too. The two produced some near-perfect musical collaborations, according to critics – heard on songs like “This Year’s Kisses” and “Mean To Me.”

Screen shot from 1972 Billie Holiday film (w/Diana Ross) depicting life on the road in the 1930s w/ band, which for a black woman among mostly men, had its share of racial & privacy indignities. Click for DVD.

Even with Shaw’s orchestra, some backers and promoters objected to Holiday for racial reasons, and others for her unique vocal style. At the time, some listeners were not ready for the interpretive liberties she took with old standards.

In New York in 1938, Artie Shaw’s band was playing at the upscale Lincoln Hotel, with nationwide broadcasts over the RCA radio network. However, some of the sponsors had complained about Billie “ruining the tune,” and so, she was limited to one or two songs during the hour show.

In addition to this, the owner of the Lincoln Hotel objected to Billie sitting at the bar or mixing with customers, and was also told she could only use the tradesmens’ entrance and the freight elevator. Although Shaw and his bandmates were outraged over Billie’s treatment, and objected to the owner, Billie had to comply. In any case, she ended up leaving Shaw’s orchestra. By then her music was becoming recognized nationally.

In September 1938, Holiday’s single “I’m Gonna Lock My Heart” ranked 6th among most-played songs that month. Her record label, Vocalion, listed the single as its fourth best-seller in that same period, with others later ranking it as the No. 2 most popular song of that time. But by the late 1930s, Billie Holiday was out her own, and that’s when she began freelancing and performing at the Café Society nightclub. In addition to debuting “Strange Fruit” there, she also debuted “God Bless the Child” there, a song which she also co-wrote that became a hit and sold more than million copies.

Other Holiday songs were about her relationships, such “T’ain’t Nobody’s Business if I Do,” “My Man,” and others. Some were songs of destructive and abusive relationships which had come her way. By the early 1940s, Holiday was into alcohol and smoking opium. Her recording career, meanwhile, had continued with Decca Records, putting out more popular songs.In September 1943, Life magazine offered that Holiday “has the most distinct style of any popular vocalist and is imitated by other vocalists.” As noted by writers, music historians, and biographers such as Bud Kliment and Arnold Shaw, Holiday’s success in the early 1940s was partly due to her becoming a torch singer, as many people identified with her songs about loneliness and lost love, especially given the separations of World War II then affecting millions.

“Billie’s tortured style, the sense of hurt and longing,” observed historian Arnold Shaw, “may have been a perfect expression of what servicemen and their loved ones were feeling.”

In 1944, Holiday garnered her first jazz critics’ poll victory – Esquire magazine’s “Gold Award” for best female vocalist. In 1945 she produced, among others, the No.5 R&B hit “Lover Man.” However, when her mother died in October 1945, Holiday’s use of alcohol and drugs escalated. Because of her narcotics conviction, Holiday’s New York “cabaret card” – a license to perform in nightclubs – was revoked.Still, she remained a major star in the jazz world, and also appeared in a minor role as a maid, along with her idol, Louis Armstrong, in the 1947 film, New Orleans. But also that year, Holiday was arrested and convicted for narcotics possession, sentenced to one year in a federal rehabilitation prison. In 1948, just ten days after serving her term and leaving prison, she performed to a packed house at Carnegie Hall on March 27th. She sang about 30 songs during that appearance. But beyond such high profile concerts, Holiday’s life as a working singer was severely restricted. Because of her narcotics conviction, Holiday’s New York “cabaret card” – a license to perform in nightclubs – was revoked. One New York club, however, The Ebony Club, allowed her to perform, as the club’s owner, John Levy, would became her boyfriend and manager by the end of the 1940s. Levy, however, was among those men in Holiday’s life who took advantage of her. Around this time as well, she was arrested on narcotics charges, but later acquitted.

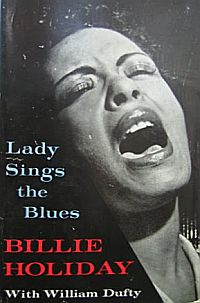

1956 Billie Holiday autobiography with NY Post writer William Dufty, published by Doubleday. Click for book.

In 1957, Billie Holiday performed at the Sugar Hill nightclub in Newark, New Jersey and the Newport Jazz Festival in Rhode Island. And despite trouble she had been experiencing with her voice, she managed to give an impressive performance on the 1957 CBS television broadcast, The Sound of Jazz. This one-hour TV show, which aired on December 8, 1957, was one of the first major programs featuring jazz on American television. It brought together an all-star cast of 32 leading jazz musicians including: Count Basie, Lester Young, Ben Webster, Jo Jones and Coleman Hawkins, Henry “Red” Allen, Vic Dickenson, Roy Eldridge, Pee Wee Russell, and younger musicians such as Gerry Mulligan, Thelonious Monk, and Jimmy Giuffre. But one of the high points of the show was the performance of “Fine and Mellow,” reuniting Billie Holiday and her old friend Lester Young, who played the first solo. Music critic and writer Nat Hentoff, who was also involved with the telecast, recalled that when Young rose to play his part:

“… he played the purest blues I have ever heard, and [he and Holiday] were looking at each other, their eyes were sort of interlocked, and she was sort of nodding and half–smiling. It was as if they were both remembering what had been… And in the control room we were all crying…”

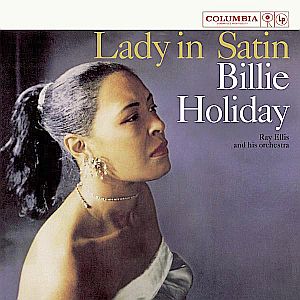

The Billie Holiday album “Lady in Satin” was originally recorded in 1958, and reissued in 1997. Click for CD.

“…I would say that the most emotional moment was her listening to the playback of “I’m a Fool to Want You.” There were tears in her eyes… After we finished the album I went into the control room and listened to all the takes. I must admit I was unhappy with her performance, but I was just listening musically instead of emotionally. It wasn’t until I heard the final mix a few weeks later that I realized how great her performance really was.”

On March 15, 1959, Billie’s old friend, Lester Young, died in New York at the age of 49. Young’s passing was taken very hard by Holiday, then believing her own time was limited. She gave her final performance in New York City on May 25, 1959. Not long after, Holiday was admitted to the hospital for heart and liver problems. She was addicted to heroin at that point was very weak from her illnesses. On July 17, 1959, Holiday died from alcohol- and drug-related complications. She was 44 years old. Her bank account at the time recorded a few dollars at best, though royalties due her at that year’s end totaled some $100,000.

|

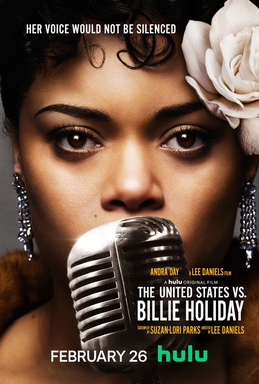

“Targeting Billie”  1930. Harry Anslinger, when he became Commissioner of the U.S. Bureau of Narcotics. Anslinger served as the first commissioner of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics – a post he filled after first serving as a federal prohibition enforcer. Once prohibition ended he then became the nation’s first drug czar in 1930, remaining in that position for 32 years, from the Hoover Administration through the Kennedy years, until 1962. A rabid anti-marijuana and anti-drug crusader, and also a racist who sought to convict high profile jazz musicians, Anslinger would develop a particular vendetta against Billie Holiday. Sometime in the 1940s, it appears, Anslinger had warned Holiday she should stop performing her song, “Strange Fruit.” Holiday refused, which moved Anslinger to come after her all the more, assigning undercover agents to befriend her, plant drugs on her person or at her residence, recruit informers to betray her, and finally prosecute her for drug possession. A 2015 book by Johann Hari, Chasing the Scream: The First and Last Days of the War on Drugs, includes profiles of Anslinger and his campaign against Holiday. Anslinger reportedly made numerous racist observations about African Americans and that black jazz musicians were especially dangerous. He charged that jazz, in particular, was “Satanic” music, created under the influence of marijuana. In his book, Hari would write: …Jazz was the opposite of everything Harry Anslinger believed in. It is improvised, and relaxed, and free-form. It follows its own rhythm. Worst of all, it is a mongrel music made up of European, Caribbean and African echoes, all mating on American shores. To Anslinger, this was musical anarchy, and evidence of a recurrence of the primitive impulses that lurk in black people, waiting to emerge…  2021 film, “The United States vs. Billie Holiday,” includes story of government surveillance of Billie Holiday. Click for Amazon. In 1959, Holiday checked herself into a New York City hospital, then suffering from heart and lung problems and cirrhosis of the liver due to decades of drug and alcohol abuse. She feared she would never come out of the hospital alive, believing the government was out to get her, as Anslinger was still following her. It is believed Anslinger had his men go to the hospital and arrest her for drug possession. There she was handcuffed to her bed where agents took mugshots, removed flowers and gifts from visitors, and stationed two cops at the door. Although Holiday had been showing signs of recovery in the hospital, as doctors began methadone treatments, Anslinger’s men forbid doctors to give her further treatment. She died within days. A 2021 Hollywood film, titled “The United States vs. Billie Holiday,” focuses, in part, on Holiday’s dealings with Anslinger’s federal agents – and in particular, her relationship with one black agent sent to track her who becomes involved with her. The film, directed by Lee Daniels and written by Suzan-Lori Parks, is inspired by the Johann Hari’s book mentioned above, Chasing the Scream: The First and Last Days of the War on Drugs, and stars Andra Day as Billie Holiday. |

David Margolick’s book, “Strange Fruit: Billie Holiday and the Biography of a Song,” Click for copy.

Kudos & Legacy

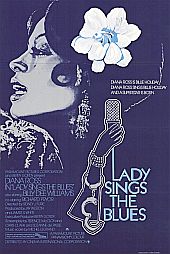

Years after her death, Billie Holiday received numerous awards and other cultural recognition. In 1972, Diana Ross, former lead singer of the 1960s’ Motown group The Supremes, played the role of Billie Holiday in the film Lady Sings the Blues, which sparked renewed interest in Holiday’s music.

A number of Billie Holiday songs have been inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame, including: “God Bless The Child” (1976), “Strange Fruit” (1978), “Lover Man” (1989), “Lady In Satin” (2000), and “Embraceable You” (2005). She has also received Grammys in the Best Historical Album category: Billie Holiday – Giants of Jazz (1980), Billie Holiday – The Complete Decca Recordings (1992), The Complete Billie Holiday (1994), and Lady Day: The Complete Billie Holiday (2002).

Billie Holiday has also been honored with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame and in September 1994, the U.S. Postal Service issued a stamp in her honor in the “Jazz & Blues Singers” series. Numerous fellow musicians have covered her songs, with some offering special tributes. In 1988, the Irish rock group U2 released a Billie Holiday tribute song titled “Angel of Harlem.”

In 2000, with Diana Ross as her presenter, Billie Holiday was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

Abel Meeropol, meanwhile, the author of the original poem and song, “Strange Fruit,” sustained his family, in part, on his share of the music publishing fees from that song and another he wrote about racial intolerance, “The House I Live In,” a song that Frank Sinatra and others sang in the 1940s and 1950s.But it was Billie Holiday’s interpretation and performances of “Strange Fruit” that helped bring public attention to the racial injustice of that time and earlier, leaving powerful instruction still.

See also at this website, “Civil Rights Topics, 1930s-2010s,” for additional stories in that category, and also, “Noteworthy Ladies,” a topics page with additional story choices on famous women in various fields. More stories on music history may be found at the “Annals of Music” category page.

Thanks for visiting – and if you like what you find here, please make a donation to help support the research, writing and continued publication of this website. Thank you. – Jack Doyle

|

Please Support Thank You |

__________________________________

Date Posted: 7 March 2011

Last Update: 11 February 2021

Comments to: jackdoyle47@gmail.com

Article Citation:

Jack Doyle, “Strange Fruit, 1939-2020s,”

PopHistoryDig.com, March 7, 2011.

__________________________________

Sources, Links & Additional Information

Billie Holiday, undated. |

“Billie Holiday Hailed in Solo Jazz Concert,” New York Times, February 17, 1946.

“Billie Holiday Revue; Singer Opening at the Mansfield Tonight in Jazz Feature,” New York Times, April 27, 1948.

“Holiday’s Revue Laden With Stars; Singer’s 14 Numbers Highlight of Jazz Program Given at the Mansfield Theater,” New York Times, April 28, 1948, Section, Amusements, p. 33.

“Singer Freed on Opium Charge” (B. Holiday freed on opium charge, San Francisco…), New York Times, June 5, 1949.

“Song Story Told by Billie Holiday; Excerpts of Autobiography Read at Carnegie Hall Give Meaning to Recital…,” New York Times, November 12, 1956.

Bret Primack, “Billie Holiday: Assessing Lady Day’s Art and Impact,” As published by: JazzTimes; includes short, first-person reminiscences on Billie by jazz artists and others.

Billie Holiday and William Dufty, Lady Sings the Blues, New York: Doubleday, 1957.

John S. Wilson, “Billie Holiday — Jazz Singer, Pure and Simple,” New York Times, July 6, 1958.

Chris Albertson, Interview with Billie Holiday, WHAT-FM, Radio, Philadelphia, PA, 1958.

WNET’s American Masters series, “The Long Night of Lady Day,” 1986.

Stephen Holden, “Billie Holiday Documentary on 13,” New York Times, August 4, 1986.

Michael Brooks, Billie Holiday Biogra- phical Notes, Booklet with CD Box Set: Billie Holiday – The Legacy, Columbia Jazz Master-pieces, 1991.

Steven Lasker, Billie Holiday Recording Notes, Booklet with CD Box Set: Billie Holiday – The Complete Original American Decca Recordings, MCA Records, April 1991.

Stuart Nicholson, Billie Holiday, Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1995.

Donald Clarke, Billie Holiday: Wishing on The Moon, New York: Da Capo Press, 2000.

David Margolick, Strange Fruit: Billie Holiday, Cafe Society, And An Early Cry For Civil Rights Philadelphia & New York: Running Press, April 2000, 160 pp.

“Strange Fruit,” Film, PBS, Independent Lens, 2003.

“Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith,” Wiki- pedia.org.

Radio Diaries, “Strange Fruit: Anniversary Of A Lynching,” National Public Radio, August 6, 2010.

“Billie Holiday, April 7, 1915-July 17, 1959,” Biography.com.

“Billie Holiday,” Wikipedia.org.

Jesse Hamlin, “Billie Holiday’s Bio, ‘Lady Sings the Blues,’ May Be Full of Lies, But it Gets at Jazz Great’s Core,” San Francisco Chronicle, September 18, 2006.

“Birthday Spotlight for April 7th: Billie Holiday – A Billie Holiday Tribute…By Confetta for Everyone..,”Crooners & Songbirds, April 6, 2009.

Billie Holiday Discography, The Original LP Discography, BillieHolidaySongs.com.

Hettie Jones, section on Billie Holiday from, Big Star Fallin’ Mama: Five Woman in Black Music, New York: Viking Press,

Geoffrey C. Ward and Ken Burns, Jazz: A History of America’s Music, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2000.

“The Sound of Jazz,” Wikipedia.org.

Nat Shapiro, Nat Hentoff (eds), Hear Me Talkin’ to Ya: The Story of Jazz as Told by the Men Who Made It, New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1966, 429 pp.

John Chilton, Billie’s Blues: The Billie Holiday Story, 1933-1959, New York: Da Capo Press, 1989.

Robert O’Meally, Lady Day: The Many Faces of Billie Holiday, New York: Da Capo Press, 1991.

Julia Blackburn, With Billie: A New Look at the Unforgettable Lady Day, New York: Vintage Books, 2006.

Peter Daniels, “Strange Fruit: The Story of a Song,” WSWS.org, February 8, 2002.

“Harry Anslinger,” Wikipedia.org.

John C. McWilliams, The Protectors: Harry J. Anslinger and the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, 1930-1962, University of Delaware Press, 1990.

Johann Hari, “The Hunting of Billie Holiday: How Lady Day was in the middle of a Federal Bureau of Narcotics fight for survival,” Politico.com, January 17, 2015.

Malak Monir, and Jessica Durando, “100 Facts about Billie Holiday’s Life and Legacy,” USA Today.com, April, 7 2015.

Brandon Weber, “How ‘Strange Fruit’ Killed Billie Holiday,” The Progressive/progres-sive.org, February 20, 2018.

Eudie Pak, “The Tragic Story Behind Billie Holiday’s “Strange Fruit”, Biography.com, April 5, 2019.

“All Things Considered,” National Public Radio / NPR.org, “Looking Back At Jazz Singer Billie Holiday’s Influence On American Music,” August 22, 2019.

“Throughline,” National Public Radio / NPR.org, “Strange Fruit,” August 22, 2019.

__________________